Public Relations Research

The Key to Strategy

Although public relations is an exciting and dynamic field demanding people with strong communication skills and adept at social media, the key to strategic public relations and communication management is research.1 We can argue that as much as three-quarters of the public relations process (detailed in Chapter 9) is based on research knowledge: research, strategic action planning, and evaluation. There are four reasons that research offers the key to strategy for communication:

- Research contributes to ethics because it makes communication a two-way process by collecting input from publics (rather than using a simple dissemination of information).

- Research makes public relations activities strategic by ensuring that communication is specifically targeted to publics who want, need, or care about the information.

- Research allows us to show results, to numerically measure impact, and to refocus our efforts based on those numbers.

- Research offers a basis to advise the dominant coalition in CEO on strategy.

Research forms the basis for strategic public relations. Although it may be conducted in-house or contracted to a research firm, each public relations manager must know a great deal about research.

Formative and Evaluative Research in Public Relations Management

Data collection is conducted at least twice during a public relations initiative: to formulate strategy, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the strategy. Formative research is the process of gathering data and information to help develop effective public relations strategies. Evaluative research measures the effectiveness of public relations activities over the campaign.2

Formative research provides insights into factors contributing to a situation and evaluates awareness, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors of stakeholders that help the organization form strategies and set benchmarks for evaluating the effectiveness of communication efforts. To understand the value of formative research, consider the following case.

A community hospital in a midsized city located in the Mountain West is part of a larger health-care system and offers almost all hospital services except major surgeries. It is known as one of the best hospitals in the state for pregnancies and childbirth. However, the patient intake is declining and the administrators want to develop a strategy to increase its use. Prior to conducting research, the hospital speculates that one of the primary causes is its location. It is situated off the main traffic routes, therefore has very little visibility. Administrators believe that not enough publicity has been generated to create awareness of its excellent services.

An awareness and opinion survey is conducted among random residents of the city. The results indicate that the majority are aware of the hospital, its services, and its excellent reputation. This quantitative research (typically consisting of numeric data) suggests that lack of awareness is not the likely source of the decline in patients. Interviews are conducted with administrators of health clinics in the community. From this qualitative research (typically consisting of nonnumerical data and more in-depth in nature), the health-care system learns that several of these clinics offer many of the same services as the hospital and are taking away business because of the convenience of those clinics. They also learn that the clinics are not aware of the additional services the hospital provides and its reputation for its childbirth facilities. The clinics are referring patients to a competing hospital that has made more efforts in building a positive relationship with the clinics.

From this formative research, the health-care system avoided wasting significant money on publicity and promotion, which would not have resulted in increased patients. Strategically, it focused efforts on improving long-term relationships with the clinics and physicians who make referrals to a hospital.

Evaluative research is used to assess the effectiveness of public relations efforts. After formative research establishes benchmarks in awareness, understanding, opinions, attitudes, and behaviors, evaluative research can test whether public relations efforts have made improvement in these areas. Evaluative research is usually conducted in three areas: Outputs, outtakes, and outcomes. These are defined in the Dictionary of Public Relations Measurement and Research in the following ways:3

Output: What is generated as a result of a PR program or campaign that may be received and processed by members of a target audience. This measures the content generated by the organization that appears before an audience.

Reach (the size of the audience) and frequency (how often the message appears) are the most frequently used variables to measure output; tone (positive, neutral or negative) can also be measured. In earned media, such as news releases, the organization loses control over the tone. When measuring output, the organization is really measuring Opportunities to See (OTS) of a message—not the actual impact of the message.

Outtake: Measurement of what audiences have understood and/or heeded and/or responded to a communication product’s call to seek further information from PR messages prior to measuring an outcome.

Outtakes measure message consumption. Did the audiences see, understand, and remember the messages? This information is much more useful than simplistic output measures alone.

Outcomes: Quantifiable changes in awareness, knowledge, attitude, opinion, and behavior levels that occur as a result of a public relations program or campaign.

Ultimately, what organizations want to measure is the impact of the communication messages on their audiences—their behavioral changes due to the campaign. The results can be short-term or long-term changes.

Research takes many forms: formal or informal, primary or secondary, and quantitative or qualitative. The key to conducting good research is to determine the best method of answering your questions.

Informal and Formal Research

Informal research is usually collected on an ongoing basis by managers, from sources both inside and outside their organizations. It is the gathering of information from key stakeholders by asking questions, talking to members of publics or employees, scanning social media, reading e-mails or questions from customers, and scanning the news and trade press. Informal research comes from the boundary spanning role of public relations, meaning that contact is maintained with publics (external and internal). A great deal of time is spent in communicating informally with these contacts, in an open exchange of ideas and concerns. This is one way in which public relations managers can keep abreast of changes in an industry, trends affecting the competitive marketplace, issues of discontent, the values and activities of activist groups, the innovations of competitors, and so on. Informal research methods are usually nonnumerical and are not generalizable to a larger population, but they yield a great deal of insight. The data yielded from informal research can be used to examine or revise organizational policy, to craft messages in the phraseology of publics, to respond to trends, to include the values of publics in new initiatives, and numerous other derivations. Issues management (Chapter 10) relies heavily on informal research methods.

Formal research is planned research of a quantitative or qualitative nature, asking specific questions about topics of concern. In formal research, the method must follow standards that increase the validity and reliability of the data collected. For the data to be statistically significant and meaningful, the researcher must use formal research. Formal research can be used for both formative and evaluative purposes. Most of this chapter is dedicated to formal research methods.

Primary and Secondary Research

Research in public relations management requires the use of specialized terminology. The term primary research is used to designate unique data collection of proprietary information, firsthand, and specifically relevant to a certain client or campaign.4 Primary research, because it is unique to the organization and research questions, is often the most expensive type of data to collect. Secondary research refers to research that is normally a part of the public domain but is applicable to a client, organization, or industry, and can be used to round off and support the conclusions drawn from primary research.5 Secondary research is normally accessed through the internet or is available at libraries or from industry and trade associations. Managers often use secondary research as an exploratory base from which to decide what type of primary research needs to be conducted. With the easy availability of information on the internet, researchers have to be careful about the validity and reliability of this information.

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

All primary research will fall under the categories of quantitative or qualitative research. Quantitative research seeks a large quantity of responses so that data are a numerical value using statistics. Qualitative research seeks a deep quality of detail responses so that in-depth understanding or explanation can be achieved. Most public relations research plans collect both quantitative and qualitative data, termed “mixed method,” to achieve a robust understanding of the situation. Social media metrics offer a good example of mixed method data using both numerical measurement and qualitative analysis to understand what drove the numbers.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is based on statistical generalization. Surveys are synonymous with public opinion polls and are one example of quantitative research (see Table 8.1 which lists quantitative research methods commonly employed in public relations). It allows us to make numerical observations such as “85% of Infiniti owners say that they would purchase an Infiniti again.” Statistical observations allow us to know exactly where we need to improve relationships with certain publics, and we can then measure how much those relationships have ultimately improved (or degraded) at the end of a public relations initiative. For example, a report from automobile manufacturer Infiniti may include a statement reading: “11% of new car buyers were familiar with the all-wheel-drive option 3 months ago; after our campaign 25% of new car buyers were familiar with this option; we created a 14% increase in awareness.” Quantitative research allows a before and after snapshot to compare the numbers in each group, therefore we know how much change was evidenced as a result of public relations’ efforts.

The entire public whom you wish to understand or make statements about is called the population. The population may be women over 40, registered voters, purchasers of a competitor’s product, or any other group that you would like to study. From that population, you would select a sample to actually contact with questions. Probability samples can be randomly drawn from a list of the population, which gives you the strongest statistical measures of generalizability. A random sample means that participants are drawn randomly and have an equal chance of being selected, so that the sample data is generalizable to the population. You know some variants in your population exists, but a random sample should account for all opinions in that population. The larger the sample size (number of people responding, who are termed respondents), the smaller the margin of error and the more confident (sometimes referred to as a confidence interval) the researcher can be that the sample is an accurate reflection of the entire population. Being an accurate representation includes both reliability (confidence in accuracy) and validity (that the measurement reflects the phenomenon under study).

There are other sampling methods, known as nonprobability samples, which do not allow for the generalization of a whole population, but meet the requirements of the problem or project. A convenience sample, for instance, is drawn from those who are convenient to study, such as having visitors to a shopping mall fill out a survey. A snowball sample asks someone completing a survey to recommend the next potential respondent to complete the survey (often used in social media surveys).

A purposive sample is when you seek out a certain group of people. These methods are often less expensive than random sample methods and still may generate the type of data that answers your research question. Many forms of online data are available for purchase that may be used in this manner with varying levels of statistical trustworthiness.

Quantitative research has the major strength of allowing you to understand who your publics are, where they get their information, how many believe in certain viewpoints, and which communications create the strongest resonance with their beliefs. In other words, it provides us with normative outcomes that can later be broken down to better understand subgroup norms. Demographic and psychographic variables are often used to segment publics. Demographics are usually gender, education, race, profession, geographic location, annual household income, political affiliation, religious affiliation, and size of family or household. Psychographics classify audiences by their attitudes, values and lifestyles. Netgraphics classify audiences by their social media use. Often the demographics are cross-tabulated with opinion and attitude variables to identify specific publics who can be targeted with future messages in the channels and the language that they prefer. For example, in conducting public relations research for The National Park Service, cross-tabulating data with survey demographics might yield a public who are males, are highly educated and professional, exercise outdoors three times per week, have an annual household income above $125,000, usually vote conservatively, have religious beliefs, have an average household size of 3.8 people, and 42 percent strongly agree with the following message: “National Parts offer great recreation opportunities.” In that example, you would have identified a voting public who support national parks.

Segmenting publics in this manner is an everyday occurrence in public relations. Through segmentation, managers have an idea of who will support the organization, who will oppose it, and what values and messages resonate with each public. After using research to identify these groups, we can then build relationships with them in order to conduct informal research, better understand their positions, and help to represent the values and desires of those publics in organizational decision making and policy formation.

Qualitative Research

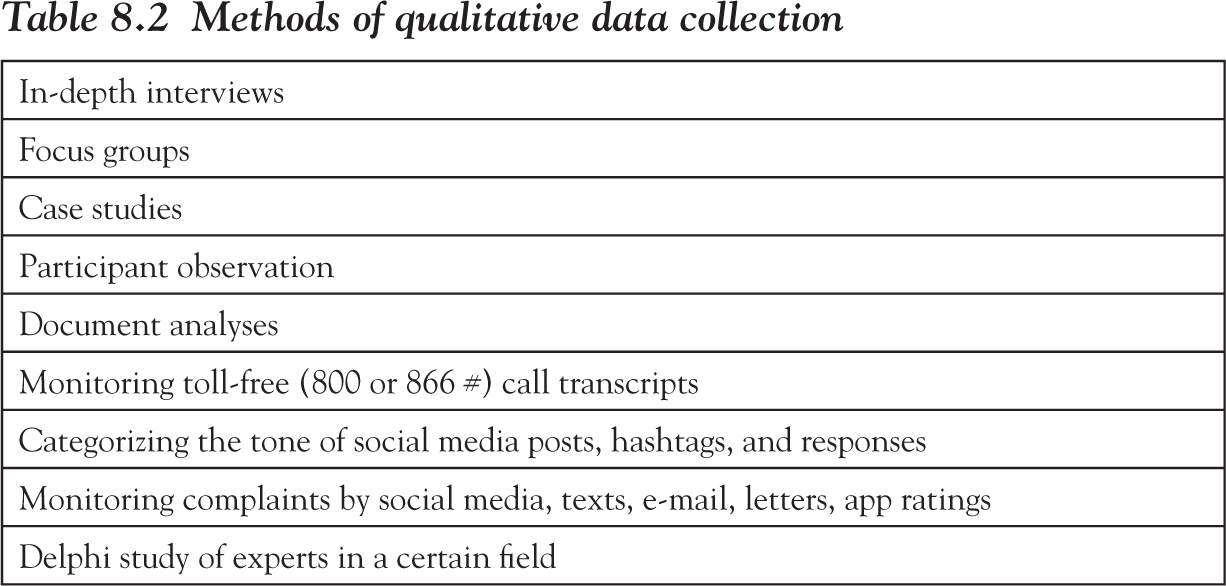

Qualitative research generates in-depth, “quality” data to understand public opinion, but it is not statistically generalizable (see Table 8.2 which lists qualitative research methods commonly employed in public relations). Qualitative research is enormously valuable because it allows us to truly learn the experience, values, priorities, and viewpoints of our publics.

Qualitative research is particularly adept at answering questions from public relations practitioners that began “How?” or “Why?”6 This form of research allows the researcher to ask the participants to explain their rationale for decision making, belief systems, values, thought processes, and so on. The main benefit is that it allows researchers to explore complicated topics to understand the meaning behind them and the meanings that participants ascribe to certain concepts. For example, a researcher might ask a participant, “What does the concept of liberty mean to you?” and get a detailed explanation. However, we would expect that explanation to vary among participants, and different concepts might be associated with liberty when asking an American versus an Iraqi. Such complex understandings are extremely helpful in integrating the values and ideas of publics into organizational strategy, as well as in crafting messages that resonate with specific publics.

Managers often use qualitative research to inform, explain, and support quantitative findings, a process called “triangulation.” Qualitative research can be designed to understand the views of specific publics and to have them elaborate on beliefs or values that stood out in quantitative analyses. For example, if quantitative research showed a strong agreement with a particular statement, that statement could be shared with focus group participants to add rationale and thought processes behind their choice. In this manner, qualitative researchers can understand complex reasoning and dilemmas in much greater detail than only through results yielded by a survey.7

A benefit of qualitative research is that it is exploratory, so it can be used to discover data that researchers did not suspect or know they needed. For instance, a focus group may take an unexpected turn and yield statements that the researcher had not thought to include on a survey questionnaire. Sometimes unknown information or unfamiliar perspectives arise through qualitative studies that are extremely valuable to public relations’ understanding of the issues impacting publics.

Another strength of qualitative research is that it allows participants to speak for themselves rather than to use the terminology provided by researchers. This benefit can often yield a greater understanding that results in far more effective messages than when public relations practitioners attempt to construct views of publics based on quantitative research alone. Using the representative language of members of a certain public often allows us to build a more respectful relationship with that public. For instance, animal rights activists often use the term “companion” instead of “pet”—that information could be extremely important to organizations such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA).

Mixed Methods or Triangulation

Quantitative and qualitative research have complementary and unique strengths. These two research methods should be used in conjunction whenever possible so that both publics and issues can be fully understood. Using both of these research methods together is called mixed method research, and scholars generally agree that mixing methods yields the most reliable research results.8 It is best to combine as many methods as is feasible to understand important issues. Combining multiple focus groups from various cities with interviews of important leaders and a quantitative survey of publics is an example of mixed method research because it includes both quantitative and qualitative methods. Using two or more methods of study is sometimes called triangulation, meaning using multiple research methods to triangulate upon the underlying truth of how publics view an issue.9

Special Considerations

Social Media Measurement

With the increased use of social media, many organizations have taken steps to measure its impact among publics. Rapid changes mean a lot of variance in the practice of social media, and research on it. Standards have been set for ethical use of social media,10 and research ethics as related to social media measurement.11 Industry, research, and academic leaders met to set standards for the measurement of social media to improve consistency across industries and organizations. Through these standards, the data can be compared consistently and with greater reliability and validity.12

The six standards are:

- Content and Source: This metric provides transparency in social media measurement to show how content is defined and its source, allowing measurement to be consistent across companies and platforms.

- Reach and Impressions: This output metric measures how messages reach intended audiences, with these components:

- An item of content is a post, micro-post, article, or other instance appearing for the first time in a digital media.

- A mention refers to a brand, organization, campaign, or entity that is being measured. Mentions are typically defined in social media using Boolean search queries.

- Impressions represent the number of times an item has an opportunity to be seen. It typically counts the same individuals multiple times and will include those who had the opportunity to see the item, but did not in fact see it at all.

- Reach is the total number of individuals who had the opportunity to see an item, eliminating the duplication of individuals who have had the opportunity to see the item through multiple channels/devices.

- Engagement and Conversation: This outtake measurement uses content analysis to evaluate what audiences are doing with the messages.

- Engagement is defined as an action beyond exposure, and implies an interaction between two or more parties. Engagement counts such actions as: likes, comments, shares, votes, retweets, views, content embeds, and so on.

- Conversation is defined as online or off-line discussion by publics, stakeholders, influencers, or third parties; Conversation counts blog posts, comments, tweets, Facebook posts/comments, video posts, replies, and so on.

- Opinion and Advocacy: Output measures using content analysis to evaluate attitudes and opinions expressed in social media.

- Sentiment as feeling is a component of opinion and advocacy, often measured through context surrounding characterization of object.

- Opinion is a view or judgment formed about something, not necessarily based on fact or knowledge.

- Advocacy is a public statement of support for, or recommendation of, a particular cause or policy. Advocacy requires a level of expressed persuasion. The key distinction between “advocacy” and “opinion” is that advocacy must have a component of recommendation or a call to action embedded in it.

- Influence: The definitions of what constitutes influence and influencers reflects the standards set by the Word of Mouth Marketing Association (WOMMA). Influencer Marketing is: The act of a marketer or communicator engaging with key influencers to act upon influencees in pursuit of a business objective. Where each term is defined as:

- Influence is the ability to cause or contribute to change in opinion or behavior.

- Where the initial actor is a key influencer who is: A person (or group) who possess greater than average potential to influence due to attributes such as frequency of communication, persuasiveness, or size/centrality of a social network.

- Influencees are persons or groups who change their opinion or behavior as the result of exposure to information presented by influencers.

- Impact and Value: These represent the ultimate outcome of a social media effort. The impact and value of a campaign is defined by and dependent on the goals of the program and the organization. It can include financial goals, such as sales, and other desirable outcomes such as increased reputation, trust, and improved relations with key stakeholders. Social media data are usually corroborated with other data such as sales, opinion surveys, and so on.

Even with these standards, there is still a lot of room for interpretation and variation. Thus, researchers must provide transparency about the way these terms were defined and analyzed when reporting results.

Big Data

The ever-increasing capacity to gather enormous amounts of data regarding opinions, attitudes and behaviors has forever changed the landscape of strategic planning for businesses. Through internet monitoring, social media tracking, personal device data gathering, organizations can gather or purchase data on millions of people that give more insight into human behavior than was previously available. While enormous amounts of data are available, the challenge is in managing and analyzing the data in ways that meaningfully enhance strategic planning. Analysts can create a variety of algorithms and statistical analyses to give meaning to the data, but these are only as good as the questions they seek to answer. Scholars note this pitfall and call it big data human generated (BDHG).13 Researchers advised:

The importance of big data is not the vast quantity of information made available, but instead, it is the value that can be created to improve performance, and better understand competitors, consumers, employees, media, and other publics. Organizations must learn and recognize that data alone do not answer “why” or explain inferred insights. Uncovering insights of big data require a human element and critical thinking to create meaning.14

Artificial Intelligence

Advances in programming have made it possible for computers to self-improve in data collection and analyses, under the guidance of programming algorithms, or artificial intelligence (AI). AI is self-teaching, computer-generated recognition that finds patterns in vast amount of seemingly unrelated information that are imperceptible to standard methods. Using AI to collect, analyze, and respond to massive amounts of data offers the potential for public relations research to target individuals or groups in way that would otherwise be impossible. Once programmed, an AI algorithm is autonomous meaning that it can reveal unseen factors and make independent decisions based on incoming data. Uses of AI such as autonomous-vehicles are well known, but also includes the domains of medical diagnostics, civil services, and communication. For example, AI can use real-time location data from a mobile phone to target specific messages to publics, such as a person at a shopping mall getting a store map delivered to their mobile device. The use of AI in public relations research is still developing but holds great promise.15Ethical questions also emerge. It is possible to identify phones leaving a Weight Watchers location for the delivery of ice cream specials at a nearby location, but is that a good use of AI data?

Research comprises about three-quarters of the public relations process, from formation through its use in analysis to evaluation. The roles of formal and informal research were discussed, as well as the major approaches to research: quantitative (numerically based) and qualitative (in-depth based), as well as using both: mixed methods. Standards for measuring social media effectiveness were detailed, and advances in big data and AI were offered.

To conclude, we covered the basics of public relations research but there is far more depth: entire careers can be spent in the research industry. Study of research methods (known as methodology) is recommended for public relations managers, because managers must know, commission, and understand valid and reliable research. More information on research methods is offered in specific texts devoted to detailed research methodology in public relations.16