CHAPTER EIGHT

Culture Matters

Many executives understand that culture matters in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) but fail to address it sufficiently. Culture will be an important consideration given the diversity of Asia, and the inevitable increase in “West-East” deals. Cultural differences are not just at the national level; corporate cultures as well as local cultures will need to be dealt with. We have an eight-pronged approach to tackling culture: conducting a culture audit, putting a label to differences, maintaining communication, leveraging the 100-day plan, understanding the web of relationships, looking for hidden costs, addressing the talent challenge, and managing local expectations.

The tantalizing prospect of forming the world’s fifth-largest food and beverage company brought Japan’s Kirin Holdings and its smaller rival, Suntory Holdings, to the table in 2009. The merger talks fell apart when the discussion turned to integration. In early 2010, both parties walked away from the deal, citing a clash in corporate culture.

Publicly listed Kirin, a well-structured organization run by a professional management team, didn’t see eye to eye with the privately held Suntory, which is still controlled by the family of its original founder. Kirin wanted the merged entity to be run by an independent, professional executive team, and accused Suntory of wanting to structure the shareholding of the merged entity so the family members could retain control. After going round in circles, the companies abandoned the plan. “The two sides could not agree on how the merged firm would be run,” Kirin President Kazuyasu Kato told reporters.1

Cultural clashes can sink a merger or mire integration. One A.T. Kearney survey cited cultural differences as the number one reason for merger failure, outstripping more obvious stumbling blocks such as poor planning, unrealistic expectations, or inadequate due diligence. A culture clash can lead to poor communication, misunderstanding, uncertainty, loss of motivation among employees, and loss of key talent.

In Asia, executives working on cross-border deals have to navigate multiple cultural minefields: gaps in national culture, clashes in corporate culture, and differences in the local business culture and norms, which sometimes condone practices that can take foreign acquirers by surprise.

Managing national culture gaps is no longer just about understanding Asia. The direction of deal flow is reversing, putting a new spin on cultural integration. As Asian outbound M&A continue to rise, a growing number of Asian executives find themselves struggling to manage this “soft” side of an acquisition in the West, where American or European staff may be wary of their new foreign managers or resistant to change.

Troubleshooting these cultural gaps comes down to foresight. Planning early, doing your pre-merger legwork, and creating a road map to guide the way can bridge almost any divide.

IT’S NOT A SMALL WORLD, AFTER ALL

The growing number of acquisitions of targets in developed markets by companies from emerging Asia is putting an increasing number of Asian executives in the cultural hot seat. The stakes, in some cases, are high. Many cash-rich Asian companies are buying bigger, better-known Western companies in a bid to leapfrog to the next level by acquiring a brand, a technology, or marketing know-how. That big-bang effort could self-combust if a culture clash were to demoralize staff at the value-added target company and the key talent walked away.

To understand the challenges faced by Asian acquirers, consider the case of a large, publicly listed Indian pharmaceutical and biotechnology company that stumbled, then found its footing, early in its European acquisition spree.

The Indian company, which has a market capitalization of around $1 billion, develops and manufactures pharmaceuticals, and employs some 9,000 staff worldwide. The company, which declined to be named, and which is referred to as “Ganga” in this case study, has spent more than £11 million acquiring pharmaceutical companies in the United States, Ireland, France, and the United Kingdom.2

In 2003, Ganga bought a loss-making British drug manufacturer, dubbed C-Pharma, to get a leg up on technology and better access to markets, notes Aston Business School Professor Pawan Budhwar, co-author of the case study on the takeover, published by the Multinational Business Review. The British company had licenses to market drugs in Africa, the Middle East, and the United Kingdom. The Indian acquirer’s plan was to move the bulk drug manufacturing to India, while continuing to develop and manufacture pharmaceuticals that required more extensive research and development (R&D) in the United Kingdom. By doing this, it could improve the cost structure at the ailing British company and acquire new technologies and markets at the same time.

C-Pharma had an estimated excess labor force of about 300 employees, which hurt productivity, and the company faced high pension costs as well. It had a small portfolio of drugs and relied on sales of its animal insulin for the bulk of its revenue. Lower-cost competing products had hit sales of that core drug hard, which ultimately led to its sale to Ganga.

When Ganga took over the company, executives attempted to wipe out the existing operation and corporate culture and replace it, wholesale, with its own. Numerous leadership positions at C-Pharma were replaced by expatriate staff from India. Ganga imposed the HR policies it used in India, including a performance appraisal system that linked performance to pay, and a competency base framework for recruitment, selection, and training. Ganga’s HR staff proceeded to use its appraisal system to weed out the unproductive labor and identify the people it wanted to keep. The HR team made a conscious effort to change the culture and values of C-Pharma employees by focusing everything on productivity, quality, cost, and speed. One thing Ganga did not do was conduct a cultural audit or give its Indian managers any form of cross-cultural training during the pre-merger or integration stage.

The acquisition hit a cultural wall from the beginning. The system of performance-linked pay was alien to the British employees at C-Pharma, and they refused to accept it.3 Ganga’s Indian managers at C-Pharma demanded long hours and extra effort, which led to further tension with the British staff. In India, Ganga commanded a competitive workforce that was willing to put in extra hours, typical of much of Asia, where people routinely work late and often come in on weekends. In Europe, staff is more used to working a nine-to-five day. C-Pharma’s British staff chafed under the management style of their new Indian bosses, who were used to deference from the staff back home.

Indian companies do tend to be hierarchical, and an executive who oversees a team or a function is used to getting full compliance from staff: The boss says what needs to be done and how it needs to be done and the staff make it so. An enormous level of respect is shown to the boss and reflected through all manner of interactions and behavior. On the flip side, Indian companies tend to have a strong “family” feel that Western companies often lack. Those in charge take a personal interest in their employees and typically know and care about what’s going on in their life at home. If they need help or assistance, the manager does what he or she can to provide it. In many respects, work relationships are like family relationships: The younger, more junior people unquestioningly obey the older, more senior folk, who, in turn, take care of them personally and professionally. That can be an unusual or unwelcome dynamic in a Western corporate setting, which tends to promote a more “flat” power structure, encourage individual expression and opinion—even if it’s at odds with the boss—and respect individual privacy.

Either way, the managerial style of their new Indian bosses meshed badly with C-Pharma’s employees, who were unsettled by job losses and disgruntled at the new performance-linked pay.

Ganga U.K.’s Indian CEO described the fallout as a classic outbreak of merger syndrome: Morale plummeted, unrest spread, and C-Pharma staff started quitting. He attributed the exodus to the rapid downsizing of 300 staff, the sudden change in the management ranks, and the poor communication around the performance management policy.

The HR team, he reflected later, should have done more to educate staff on the need for change and prepare them for the changes. The employees had preconceived notions about the Indian style of management and assumed their Indian managers were going to be directive, bureaucratic, and unsympathetic to employee welfare.

After the acquisition, the new CEO changed tack. He began building personal relationships with employees, and involving them in his decision making. The HR team began “selling” the logic for change to employees and explaining the benefits they would derive from the new performance management scheme. HR staff and managers provided training for staff to equip them for their new roles and set clear goals and objectives. The HR team provided counseling sessions for stress management and cross-cultural training. Although the late start had left wounds that took time to heal and it took nearly a year of intense HR efforts before Ganga felt the acquisition would succeed, the efforts paid off. Employees who initially railed against the acquisition felt proud to be part of the Ganga family. Ganga applied the lessons it learned at C-Pharma to a string of future acquisitions in Europe, which went far more smoothly.

Other Indian companies have taken more of a go-slow or “do nothing” approach to their European acquisitions. Tata, for example, made few changes—and sent few Indian staff—to Corus Steel, Tetley Tea, and Jaguar Land Rover after it bought those companies. Instead, Tata was primarily looking to learn from its acquisitions to help launch its own global expansion, using the brands’ existing management and employees.4

Although these brands were plagued by high costs and other problems, Tata was more concerned with reaping big-picture benefits than about short-term losses. This hands-off strategy allowed the company to sidestep cultural gaps. “It’s always about talking to the shareholders, to stakeholders, to the board, to management,” Syed Anwar Hasan, managing director of Tata Limited, the European arm of Tata Sons, told The Sunday Times in April 2011. “So, when we had the Tetley acquisition (in 2000), we did not have a planeload of Indians descending on Greenford (West London) saying, ‘Okay, now it’s goodbye to the chief financial officer, goodbye to the chief technical officer.’”5

Likewise, when Tata Steel bought Corus, Ratan Tata stated that “our intention is that Corus will retain its identity for the foreseeable future, will remain an Anglo Dutch company.”6

Instead, Tata Steel created an umbrella management team, or a “group center,” that consisted of senior Corus Group and Tata Steel executives, co-chaired by Tata Steel’s managing director B. Muthuraman and Corus CEO Philippe Varin. The group center was set up to ensure a common approach across all key functions: technology, integration, finance, strategy, corporate relations, communications, and global markets.

Still, both parties had concerns. A few months after the 2007 acquisition, Corus hired Communicaid, a European culture and communications skills consultancy, to run a series of courses on understanding Indian business culture for senior Corus management in London. “We aim to minimize the impact culture can have on the relationships between Corus and Tata Steel,” Corus’ head of communications said in a statement at the time.7

Despite Tata’s relatively hands-off approach, and Corus’s bid to understand Tata, cultural differences have caused strain and frustration. In May 2011, Tata Group Chairman Ratan Tata lashed out at the work culture of British managers, citing poor performance at Corus and Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) as prime examples. Mr. Tata said managers at the two firms were unwilling to work hard in critical situations, but their Indian counterparts would work till midnight in “a war-like situation.”8

“It’s a work ethic issue. In my experience, in both Corus and Jaguar Land Rover, nobody is willing to go the extra mile,” he said in an interview with the Times Daily. “The entire engineering group at JLR would be empty on Friday evening, and you have got delays in product introduction. That’s the thing that doesn’t happen in China or in Indonesia or in Thailand or in Singapore,” he said.

Like the case of “Ganga,” the Indian pharmaceutical company that bought the ailing British drug maker, the difference in work culture between the go-go East and the more mature Western markets has emerged as a major thorn. In Asia, employees work longer hours than people in the West and, in some countries, would never dream of leaving the office before their boss does, even if it’s 7 or 8 p.m.

Whether Mr. Tata’s complaints are valid is unclear. Economic Times columnist Sudeshna Sen, who took issue with Mr. Tata’s diatribe, noted that Europeans strive to achieve a work-life balance that doesn’t exist in much of Asia. People in the West also don’t have cheap, live-in domestic help, which is common among many middle-class Asians. “If you don’t leave work by 5 p.m. to pick up your kids, chances are they’ll be left at the gates of the crèche waiting in sub-zero weather,” wrote Ms. Sen. It’s an issue more Asian companies will need to grapple with as they head West. As for Tata, the recent outburst by the company’s chairman indicates that gaps in culture, outlook, and expectations plague the company’s European operations even though years have passed since those acquisitions took place.

The challenges faced by these two Indian acquirers illustrate the pitfalls that differences in corporate culture, business norms, and national culture, which impact how people communicate, can create in a merger or acquisition. Executives can avoid these pitfalls if they know what to look for and expect the unexpected.

NATIONAL CULTURE AND COMMUNICATION: WHAT THE INTERPRETER WON’T TELL YOU

The first 100 days of a merger can set the tone of relationships and lay the groundwork for capturing synergies. Communication is everything during this critical point, yet it’s the time when cultural gaps can create the biggest pitfalls.

As discussed, many Asian cultures encourage deference to the boss, so employees don’t like to contradict their superiors or offer their opinion unless it’s solicited. That’s a bad thing when executives from an acquiring company want to understand issues at the target company and figure out what to fix and where they can wring the most synergies. Executives who have worked on mergers in Asia say they have sometimes had to get the boss to leave the room to have a productive conversation in a meeting situation.

Some Asians also don’t like giving bad news, partly because they don’t want to stick their own neck on the line or appear to come up short and partly because they want to “save face.” When Renault sent Carlos Ghosn to Japan to turn Nissan around after the two companies merged, he ran into this issue: Middle managers tried to cover up problems and reported that everything in their unit was fine. Mr. Ghosn, speaking at a private seminar, described the situation as a “garden full of hundreds of stones” that he had to turn over, one by one. He had to win each manager over and slowly wring the truth out before he could find out what the company’s myriad problems were.

Cultural differences can affect the timing and pace of mergers as well. In 2002, a Japanese technology manufacturing company and an American competitor agreed to transfer their manufacturing operations to a new stand-alone company. The Japanese company was to run the new entity. When the merger team sat down together to map out the transition, the cultural differences became apparent: Japanese people are conservative and like to move slowly during M&A, to better accommodate the unknown. Americans, on the other hand, accomplish multiple tasks in the shortest possible time. Indeed, executives from the American technology company felt “Day One,” the formal transaction target date, should take place within three months or so. The deal had been announced, and the American company wanted to move as quickly as possible to complete the merger to assure clients that it was business as usual. The Japanese, however, wanted a horizon of six or seven months to study the American company’s operations and acquire sufficient confidence about merging the two operations and operating it as one entity. “It took ages to get an agreement on anything,” says one executive involved in the deal.

People from different cultures often communicate in starkly different ways. Consider the differences between how people in China and the United States highlight the key points in a discussion. In a meeting, a U.S. executive will typically state his or her main point right away, then follow it up with supporting evidence. A Chinese executive tends to talk in a more roundabout fashion, starting off with anecdotes and illustrations, and saving the big point for the end.

Japanese people tend not to say “no” even though they disagree; in Japan, if someone hasn’t given a resounding “yes,” it’s understood by other Japanese that they don’t agree at all. Needless to say, that can be confusing to a foreign executive. During the merger talks between the Japanese technology manufacturing company and its American competitor, for example, discussions over which production line would be closed were mired by this kind of confusion. Each party wanted to maintain its own production line and wanted the other company to take the hit. The American executives argued that the Japanese company’s facility was smaller and didn’t have the same economical scale as theirs and should, therefore, be the one to be shuttered. The Japanese executives said that yes, they understood. In their minds, however, they hadn’t agreed to close the line, but the American executives thought they had.

In cross-border mergers there is “phenomenal scope for misunderstanding,” says Stuart Chambers, former chief executive of Nippon Sheet Glass. Nippon Sheet Glass bought U.K. glass manufacturer Pilkington Plc, which Mr. Chambers used to head, in 2006, and made him the CEO of the enlarged entity. Confusion over what people had said or agreed to during the merger meetings was a major problem.

“For example, at meetings during integration with various heads of departments—with professional translators, and some of the staff were proficient in English—we would agree on something and go our separate ways. Every time I would write down in an email exactly what I felt we had agreed, but about half the time it came back that that was not what we had agreed at all. If I had executed what I thought was understood, imagine the mistrust and frustration that would generate,” says Mr. Chambers.9

“It’s not a question of the words, these are translated and understood, but what is meant by those words and goals is different according to different cultures. When meeting with people from different cultures, go back and check that everyone has understood what has been agreed upon.” Some of these complexities may have played out in Mr. Chambers’ experience at the company; he resigned one year after taking on the role, citing a desire to move back home and focus on his family. He acknowledged that the decision went against the social norms in Japan, where workers often put their company first. “In that process I have learned I am not Japanese,” he told reporters in 2009.10

LOCAL BUSINESS CULTURE CAN SHAPE THE FOCUS OF A COMPANY

The amount of time that boards spend on different stakeholders varies between countries, which can further confound companies pursuing cross-border deals.

Japanese boards, for example, spend around 70 percent of their energy and commitments on customers, 25 percent on employees, and 5 percent on shareholders, said Stuart Chambers, former chief executive of Nippon Sheet Glass. Nippon Sheet Glass bought U.K. glass manufacturer Pilkington Plc and acquired Mr. Chambers, then head of Pilkington, in the process.

British and American firms, on the other hand, spend 50 percent of their time worrying about shareholders, 25 percent on employees, and another 25 percent on customers. The difference in focus can impact corporate culture, strategy, and outlook in myriad ways. Striking a compromise may be the best way forward. In the case of Nippon Sheet Glass, Mr. Chambers noted during his tenure: “I have amended my attitude to some extent, and my Japanese colleagues have done that as well.”*

*Tor Ching Li, “Nippon Sheet Glass CEO Stresses Need for Clarity—Ensuring Understanding Is Key for a Company With Different Cultures,” Wall Street Journal–Managing in Asia, April 6, 2009, page 20.

CORPORATE CULTURE MATTERS: MAKING MIXED MARRIAGES WORK

The failed merger talks between Kirin and Suntory illustrate how wide the gap can be when two different corporate cultures clash, particularly when neither party wants to give up its way of doing things. The corporate culture of a company is reflected in a multitude of ways: how decisions are made, how staff work together, how customers are approached, and how deftly the company handles and adapts to change. When companies consider a merger, they need to ask key questions: Is the other organization flat or hierarchical, is decision making decentralized or top-down, is the organization team-based, or do superstars rule the day? The issues that killed the merger of Kirin and Suntory are common in Asia and raise more questions: Is the company family-run, controlled by its founder, or run by independent professionals?

Even two companies that are publicly owned and share the same nationality can have key cultural differences.

Consider the merger of Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi Ltd and UFJ Bank Ltd: The two banks merged at the holding company level in 2004, creating Japan’s largest bank. In the typical Japanese go-slow approach to mergers, the actual banking entities continued to operate separately for another two years. In 2006, the units were finally combined into the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd.

The two banks had markedly different corporate cultures. UFJ had a market-driven culture fostered by aggressive, outspoken leaders. Mitsubishi, which was highly structured and organized, was viewed as stuffy and elitist.11 The slow pace of integration did nothing to bridge the gap; rather, it allowed the different camps to hunker in their silos, awaiting the next, slow move. When the banks finally became one, discontent set in. The hierarchical culture of Mitsubishi, the larger bank, dominated, and many good UFJ staff, unable or unwilling to adapt, left the organization. The bank continues to hold on to its number one spot, but loss of talent during any merger can only erode optimum value creation.

Failure to forge a common corporate culture during a merger can haunt a company for many years after the deal is signed.

Consider the case of Mizuho Financial Group. The Japanese financial giant was formed in 2002 by the three-way merger of Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Fuji Bank, and the Industrial Bank of Japan. The merged entity sought to cater to the leadership of each founding bank by creating a delicate balance of power: The top slots at the new group were parceled out among executives from the three founding banks, who continued to operate their own silos much as before. The awkward balancing act was criticized as inefficient and was widely seen to have weakened competitiveness and hurt earnings growth.12

It also kept the banks from forming a common culture. A survey conducted a year after the merger took place showed that many employees were dissatisfied and could not “rid themselves of the awareness of which bank they came from,” according to a Nikkei article in October 2003.

The situation came to a head during the March 2011 earthquake in Japan: Massive donation transfer requests overwhelmed Mizuho’s computer system, causing a breakdown in the bank’s network of automated teller machines (ATMs). The infighting and finger pointing that ensued shone a spotlight on the lack of cohesiveness of the bank’s deeply divided executive team. The bank announced it would shake up its executive line-up and restructure operations to regain trustworthiness after the staggering system failure.

Yasuhiro Sato, who became the bank’s new chief executive as part of the restructuring, pledged to change the corporate culture of the bank and expedite integration. “We’ll speed up working toward becoming one entity,” said Mr. Sato, who was, and will remain, head of Mizuho’s wholesale banking unit. “Earlier, it was kind of hard to tell who was really in charge of the company.”13

Mr. Sato said that cultural differences between the bank’s units represented the biggest hurdle to integrating operations. “Building a new corporate culture swiftly is my task,” Mr. Sato said at a June press conference.

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED: LOCAL BUSINESS CULTURE AND NORMS CAN BE COSTLY AND SURPRISING

Business practices that are considered unusual at home may be entirely acceptable in another country, and compliance standards vary. Both can result in hidden costs and complexities during an acquisition. This kind of business culture gap made the purchase of a Chinese freight company by a Western multinational logistics operator more complicated that anyone had anticipated.

The Chinese freight company had a strong “Clan” culture (see “Put a label on it” later in this chapter), and the founder served as something of a patriarch. A large part of his management team even came from his own home village. He demanded unflinching support on the one hand, yet “took care” of his own, handing out perks and favors to people who needed it and supported him. Many of his team members, for example, owned several of the line-haul trucks the freight company used, a status quo that the owner condoned, partly because fringe benefits such as this allowed salaries to stay low.

This practice is typical of many Chinese transportation companies. A common result, though, is that employees will delay the loading of certain line-haul trucks and wait for their own trucks to arrive or will load their own trucks with lighter freight to save on gas, allocating heavier loads to somebody else’s vehicles to maximize personal profit. Of course, this is a cause of poor performance and unreliability.

This fringe benefit approach created operational performance issues, and it posed a major post-merger problem for the multinational buyer, which followed a structured set of compliance rules, ethical guidelines, and procurement standards. It took more than a year for the acquiring company to unravel the network of side deals and impose a more merit-based corporate culture.

Poor understanding and bad management of cultural gaps and business practices has killed several cross-border mergers in China. One high-profile M&A failure involved the joint venture between food conglomerate Danone and Chinese beverage giant Wahaha. Danone, which owns a 51 percent stake in 39 Danone-Wahaha joint ventures, accused Wahaha of defrauding it by setting up its own companies to make products identical to those produced by their joint ventures, and selling branded drinks without Danone’s permission. Another example is the merger between Ernst & Young and Shanghai Dahua, which resulted in lost employees and customers due to inadequate management of different cultures and business practices.

HOW TO BRIDGE THE CULTURE GAP

Executives heading into a merger or acquisition can troubleshoot almost any cultural gap if they know what to look for, and have an action plan. Here are eight strategies to help smooth over differences and make any kind of mixed marriage work.

Do a Cultural Audit

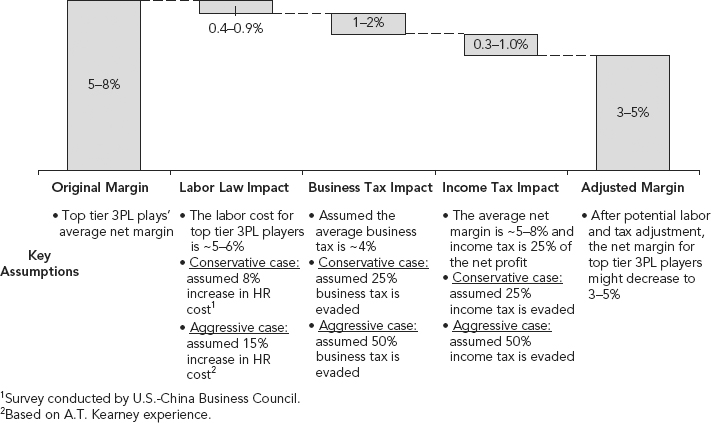

Culture is a key determinant in the success of mergers, but a limited time frame exists at the start of an integration exercise in which cultural differences can be managed before rifts and resistance set in. The program office or integration team needs to appreciate and anticipate the differences between cultures of the merging organizations and build the appropriate contingency plans into the merger plan (see Figure 8.1).

FIGURE 8.1 Identify and Proactively Address Cultural Issues That Impact the Value Capture Program

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

The key tool for this kind of pre-planning is a cultural audit. Typically conducted by an internal HR team or an HR consulting company, the cultural audit is designed to highlight the key differences in the organizations. These will include the culture inherent in the structure, systems, and processes, the prevailing management style and skills, and even the staff’s background. It should identify possible “pain points” and establish actions that can improve the situation.

Consider the audit conducted on two merging banks with different corporate cultures: The audit found that Bank A was product-centric, with a comparatively flat structure and strong internal focus on co-workers; Bank B, in contrast, was customer-centric, with a hierarchical structure and a strong external focus on customers.

The audit concluded that the management styles of the banks were different: In one, key decisions were centralized, and in the other, they were devolved to divisions. The key takeaway for the merger program office was clear: During the transition period, managers had to be aware of their precise roles and responsibilities in decision making. Any ambiguity could lead to confusion and potentially destabilize the integration.

Some audits specifically focus on differences in corporate culture and management style. Cultural audits can cover a broader range of issues, such as differences in communication style and local culture. A cultural audit can troubleshoot poor post-merger morale by helping parties on both sides understand who is acquiring them and what that will mean for individual employees since misperceptions can do more to derail morale than gaps between two company’s cultures.

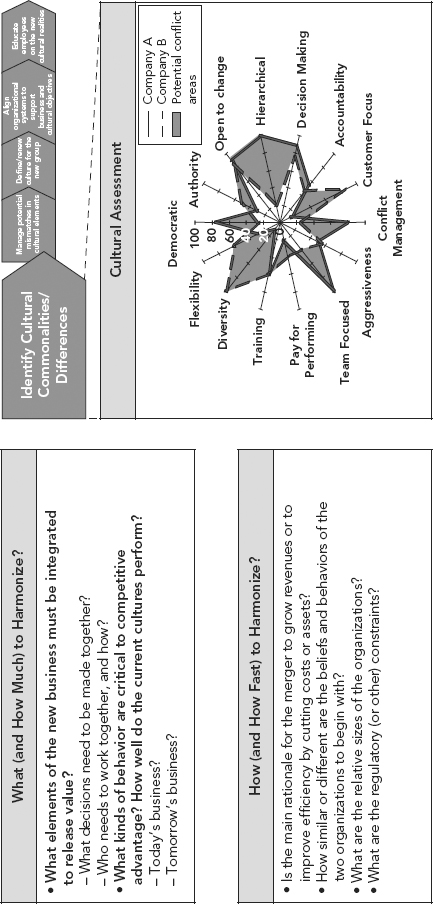

One strategy is to assemble a group of key individuals from both companies to generate a consensual view of each organization’s culture. The next step is to ask that group to create a shared vision of the desired, shared culture of the merged organization (see Figure 8.2). A good cultural audit, or assessment, can drive this exercise.

FIGURE 8.2 An Organization Culture Assessment Instrument Is a Tested Methodology for Designing Cultural Harmonization

Source: A.T. Kearney, Cameron, K., and Quinn, R. Note: OCAI—Adapted from Diagnosing and Changing Organisational Culture (1999).

When GE Capital’s Japan (GE Japan) unit bought Sanyo Electric Credit, GE’s in-house team conducted a cultural audit to help get staff from both units on board a few days after the legal merger. Sanyo Electric Credit was an established company with a major reach in the Japanese market, and GE Japan was a world-beating company with a strong brand. The HR team put together two groups from both companies, and asked the GE Japan people their perceptions of Sanyo Credit’s culture, their perception of their own corporate culture, and what they, the GE Japan staff, imagined GE Japan might look like to Sanyo. They asked the same three questions of the Sanyo team.

It became quickly apparent that both teams felt the other party had strengths they couldn’t compete with and were apprehensive about working together as a merged entity. The emphasis was on the differences between the two organizations and not the similarities. The Sanyo people, for example, felt that GE Japan had a performance-oriented corporate culture, where only top performers would flourish and be happy, and everyone else would flounder. They saw GE Japan as this global powerhouse that could back its staff with all kinds of gun power, including magic bullet strategies and tools to generate new business. The truth was that GE Japan was the result of an earlier takeover of another Japanese company, and though some of that GE Japan culture was there, it was still largely a Japanese organization. No magic bullets existed. Instead, the top performers reached their goals through hard work, the same way as Sanyo Credit’s staff had always done.

During the course of the cultural audit, staff discovered more similarities than differences between the two organizations. This realization made it easier to set common goals, create mixed teams, and get staff working together during the early days of the merger. The exercise reduced merger anxiety and moderated expectations, equally important in maintaining staff morale in the post-merger period.

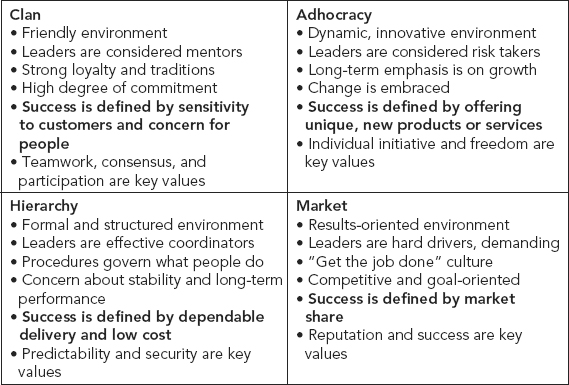

Put a Label on It

Most corporations can be categorized into one of four widely recognized organizational cultures: Clan, Adhocracy, Hierarchy, and Market (see Figure 8.3). A Clan culture is characterized by a friendly, consensus-driven environment and a strong sense of loyalty, tradition, and commitment, and it is run by leaders who are viewed as mentors. In an Adhocracy, leaders are typically risk takers who value individual initiative and foster a dynamic, innovative environment. In a Hierarchy, leaders are strong coordinators and operate in a formal, structured environment that relies on procedure and values predictability, stability, and security. A Market corporate culture promotes a result-oriented, competitive environment, meaning it’s all about getting the job done. Leaders are demanding and goal-oriented, and they drive their staff hard.

FIGURE 8.3 The Four Organizational Cultures

Source: K.S. Cameron and R.E. Quinn, Organization Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) (1999); A.T. Kearney analysis.

When companies enter merger talks or conduct a cultural audit, figuring out which category each company slots into is a good idea when it comes to corporate culture. Categorizing the company by culture can help the program office understand, before the ball gets rolling, how each party might approach things and allow merger parties to anticipate potential challenges. Two companies with different corporate cultures will mesh poorly unless the integration is handled carefully, and the program office takes those differences into account when mapping its strategy.

Consider the merger of Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi Ltd and UFJ Bank Ltd we talked about earlier. UFJ, which was run by leaders who were risk takers, belonged to the Adhocracy camp; larger Mitsubishi had more of a Hierarchy-driven corporate culture. The leaders failed to address the differences early on, and as a result, the dissimilarities festered during the slow integration. Mitsubishi’s hierarchical culture became the norm, and many UFJ staff, clinging to their identity years after the merger, resigned. If the bank’s leadership had identified the differences in corporate culture at the outset and taken steps to forge some common bonds, it could have defused the onset of merger syndrome before it became entrenched.

Communication Is Key

Failure to communicate with employees—particularly those who work for the company that’s being acquired—creates tensions and heightens cultural differences. Companies that succeed in mergers that span corporate or national cultures tend to communicate with employees from the first stages of the acquisition. To create an atmosphere that supports cultural change, companies should understand each other’s culture and people should be willing to work together after the merger. That can only be achieved with clear and regular communication between employees of the two organizations.14

The story of the Indian pharmaceutical company, Ganga, that bought the ailing British drug maker, C-Pharma, underscores the need to conduct a cultural due diligence before integration and make use of communication levers to bring about successful change. Executives interviewed after the merger conceded that many post-merger problems could have been circumvented if they had involved and communicated with employees at every stage of the process. Employees resisted change because of lack of communication, and explaining how the changes would benefit them could have brought staff on board much earlier.

When Standard Chartered Bank for South Korea bought Korea First Bank in 2005, winning over Korean employees was at the top of the agenda from day one, and communication was the key pillar of the company’s strategy. “It was a question of meeting several times a week on how are we doing, what are we communicating, what else do we need to communicate, what needs to be done?” Tom McCabe, who was chief executive officer of Standard Chartered at the time, told the Wall Street Journal. “A lot of feedback groups of employees walked the floor several times a day and would meet with different groups of staff.”

McCabe was keenly aware that a lot of uncertainty existed among employees. Several banks had merged shortly before Standard Chartered’s acquisition, resulting in significant job losses. There were differences in both organizational and national cultures that had to be bridged, as well. “People want to be dealt with as individuals, they want to be dealt with in a respectful way. So, you need to make sure you approach everything with what’s going to be the payoff, what’s in it for the employees, what’s in it for the customer, the other stakeholders, the community,” said Mr. McCabe. “So you start finding common bonds and common goals, and you work from there.”

Out of meetings with the staff came the idea for what Mr. McCabe calls the Korea Day Concept, which was designed to showcase Standard Chartered as an attractive employer. The bank sent around 100 employees from Korea to 40 markets in Asia and the Middle East, where they learned about the bank’s operations and what it was like to work there. Upon return, those employees held a series of meetings to share what they had learned with other staff. This program defused many anxieties and misperceptions about working for the bank and led to the success of the acquisition, according to McCabe.15

Leverage Your 100-Day Plan to Foster Team Spirit

A good 100-day plan can help the leadership teams from the two merged entities get organized and focused on the goals at hand. It can bring people together. In Chapter 6, we describe how a 100-day plan is a critical tool during the pre-merger and early post-merger phase. Under a typical 100-day plan, executives create joint teams and assign responsibility and goals those teams must deliver on during the first 100 days of a merger. This means the people in both entities must get to know each other and work together from the outset; the spirit of cooperation that arises naturally nips the cultural clashes in the bud that can derail a merger. A good 100-day plan delineates and times internal communications, one of the most important tools in heading off potential cultural clashes.

Consider the case of an Asian semiconductor test and assembly company that bought a U.S. competitor: Its 100-day plan, which was originally designed to focus on areas where they could capture synergies, integrate operations, and address overlapping customers, eased many concerns staff from both sides had about working for and with each other.

Going into meetings of the joint team charged with executing the 100-day plan, the Asian managers were concerned that their more assertive counterparts would dominate or resist working with them; the American employees were worried their jobs would be impacted by the acquisition. During the meetings, however, consultants facilitated discussions between the Asian managers, who spoke less, and the Americans, who expressed their views and spoke more directly and assertively. This approach helped defuse many preconceived notions and apprehensions on both sides.

Creating the joint teams, which were staffed by operational managers and their direct reports, helped convey the message that the Asian acquirer wasn’t going to come in and wipe out the entire management, and that both sides had a role in the new organization. It created a space for both sides to articulate their concerns and priorities and raise any key issues in an open manner. The acquisition and integration went smoothly, thanks in large part to the importance placed on team building under the 100-day plan.

Understand the Web of Relationships

Global companies who do M&A in places such as China need to understand the web of relationships behind local target companies. Complicated relationships often exist between suppliers, internal employees, customers, and local government officials. The initial due diligence may not uncover unethical practices that are often costly to untangle.

New entrants must navigate these relationships carefully, since they often form the basis of employees’ steady incomes. Before closing a deal, companies should seek to discover hidden incentives within the company’s relationships. After a deal, change that is too sudden or abrasive could lead to widespread dissatisfaction and sabotage. Savvy managers with an awareness of company culture and protocol are essential for building relationships. An assessment of the complex relationships and power bases will help identify “change agents” in the company, which can offer these individuals incentives to align their interests with those of the company.

That’s how A.T. Kearney helped the Western multinational logistics company troubleshoot some of the integration issues with the Chinese freight company it had acquired from its Clan-style owner. During the owner’s tenure, the web of relationships extended to relatives who supplied trucking services to the company. Moving quickly to end the system of outsourcing trucking contracts to employees’ families would have angered many; it was deemed better to take a slow approach to this sensitive issue. Regional managers ran their units like a fiefdom; so, we went to each location to explain the benefits of a more transparent, merit-driven tendering system. The company put a performance management system in place that rewarded profitability, and once regional managers realized that bringing on more efficient truckers would improve operational capacity and allow the unit to take on more business, they began to come on board. The new owner was able to find enough key stakeholders among the regional management ranks to support the move to an open, transparent tender system.

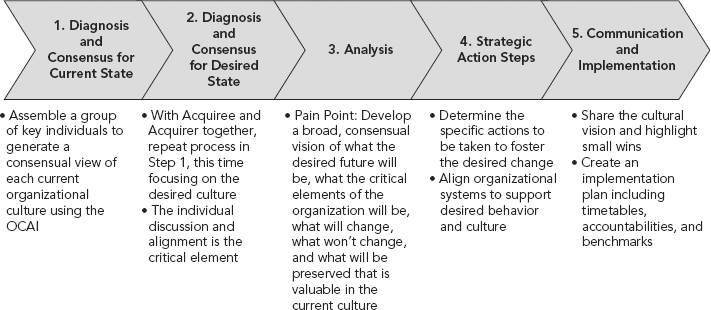

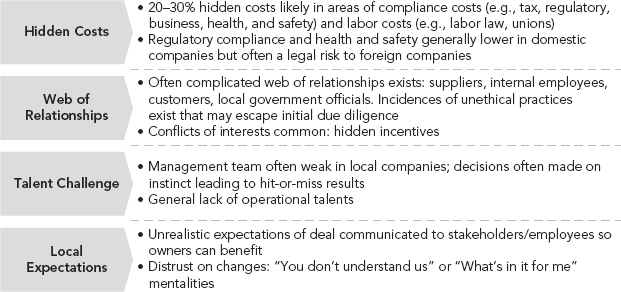

Watch for Hidden Costs

In countries such as China, compliance-related costs for a foreign company acquiring a domestic target often increase post-acquisition, sometimes as much as 30 percent. This is because foreign companies typically have stronger compliance and responsibility policies than domestic companies, which focus on expediency. Because there is reluctance to explore gray areas in tax, labor, health, and safety due to fear of corporate liability, compliance costs tend to arise after the deal is closed (see Figure 8.4 for other potential areas).

FIGURE 8.4 Potential Areas of Hidden Costs—China Logistics M&A Example

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

Let’s focus on a few key areas where compliance costs often shoot up (see Figure 8.5). Labor costs in China, for example, tend to rise by as much as 8 to 15 percent when companies move to fulfill the letter of the labor law. Many Chinese companies don’t offer all the benefits required under law, and enforcement is typically lax. When foreign companies, who must adhere to the local law to meet their own internal conduct codes, step in, costs often rise. Local companies tend to evade anywhere from 25 to 50 percent of business and income taxes. When we add all that up, the net margin could decrease by 3 to 5 percent, which can have a 2 to 4 percent negative impact on overall profitability.

Among the benefits that many companies do not offer are, for example, employee health benefits and safety programs. However, foreign entities usually cannot sustain these cost savings, as the legal and corporate risks are much higher. Imagine the ramifications if a newspaper reported the number of annual deaths caused by a lack of health and safety programs.

China has a new labor law, which may be another challenge for foreign companies struggling to control incremental costs. The law requires compliance with labor-related issues, emphasizes formal contracts, and mandates a minimum wage and social benefits. But many local companies fail to follow strictly or enforce the law. So, when a foreign buyer acquires a local company, it may face unexpected costs getting the company into compliance. Profits may appear higher because the target has not been following the labor law, an approach that’s not available to international companies, which typically have strict ethical and legal compliance guidelines.

The new law may benefit international firms, as most have such corporate labor guidelines in place, a state of affairs that levels the playing field for foreign and domestic firms and creates room for competition.

During the pre-close phase, it is nonetheless wise to conduct due diligence to understand the hidden costs that may arise after the acquisition and build this knowledge into the business case. Once the deal is done, it is important to manage incremental costs by understanding local regulations and practices.

Address the Talent Challenge

There is often a lack of educated, experienced operational talent in developing countries. Important decisions are often based on instinct rather than information and analysis, leading to hit-or-miss results.

Though acquiring companies often send finance or human resources teams to the target company, they rarely do so for operations, as they assume the new acquisition has enough capability to be successful. Yet operations are often the toughest nut to crack. Acquired companies, proud of their operations and past success, can become defensive and resistant to change. Rigorous due diligence is essential for assessing the target company’s true operational and human capabilities before a deal is agreed and ensuring the acquiring company gets what it pays for.

According to research by executive search firm Korn/Ferry International, the talent shortage in Asia is severe. Asia’s economies, once driven by manufacturing, have moved on from their role as the workshop to the world in the past few years: Domestic consumption is driving growth, and Asia’s economies, which recovered fastest from the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, are driving global growth. The kind of talent needed to succeed in this era is thin on the ground. Korn/Ferry estimates that 4 percent of managers and 5 percent of executives in Asia have the skills needed by companies today. The figure is worse in China: Just 1 percent of managers and 1 percent of executives have the competencies needed for the future.16

An acquiring company might do well to take a page from SingTel’s book. The company, which has stakes in regional mobile companies all over Asia, transfers senior-level and operational-level staff for one-year or two-year stints. This practice helps transfer learning and skill and is a key prong in the company’s bid to strengthen the local talent pool.

Providing full-time, on-site operations leadership or support with a focus on winning the trust of the local operations team can improve operational performance after a deal.

Manage Local Expectations

It is important to communicate with local workers during the acquisition process rather than leave it to the target company’s management. Many employees in domestic companies in Asia, for example, think that working for foreign companies means better salaries and an easier workload. The owner of the target company may promise employees huge salary increases or improved benefits to generate approval for a sale. When such promises go unfulfilled, the resulting distrust and low morale will hurt production. In China’s domestic logistics sector, where the companies are usually decentralized with strong local power bases, there will be resistance to top-down changes that jeopardize local interests. An effective employee communication program implemented early in the process can mitigate false and unrealistic expectations. Revamping the incentives system, building up trust and credibility, and engaging in honest communication can counteract resistance. A strong leader with first-rate people skills can help bridge cultural differences and close the talent gap.

IT’S NOT AS HARD AS IT SEEMS

Managing cultural differences in a merger or acquisition is not about erasing one culture or building a new culture from scratch. Instead, it’s about doing your research, being aware, and communicating well.

It is an ongoing challenge to cope with various cultural differences, such as regional or business-specific cultures versus corporate values and beliefs. From our experience, acknowledging cultural differences and stimulating awareness and acceptance through extensive, timely, and well-coordinated communication and the exchange of key people is more effective than designing a theoretically ideal culture from scratch.

Why? Because the target company’s people want to know their culture and heritage are not going to be discarded even as the acquirer’s staff is concerned about its culture being diluted. Failure to address these two constituencies’ concerns can lead to low morale and retention issues. The point isn’t so much to create a hybrid culture as to address these softer issues head-on before resentment and misunderstanding set in.

CULTURE CHECKLIST

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney white papers were used as background material in writing this chapter: “Making Your Chinese Merger ‘Marriage’ Work,” by Mui-Fong Goh, Chee Wee Gan, Jian Li, and Tammy Ku; “Three Years After the Marriage: Merger Integration Revisited,” by Jürgen Rothenbücher, Sebastien Declercq, Phil Dunne, Simon Mezger, Pablo Moliner, and Sandra Niewiem; “The Offshore Culture Class,” by Marcy Beitle, Arjun Sethi, Jessica Milesko, and Alyson Potenza.

Notes

1. Taiga Uranaka and Mayumi Negishi, “Japan Brewers Kirin, Suntory End Merger Talks,” Reuters, February 8, 2010.

2. Pawan S. Budhwar, Arup Varma, Anastasia A. Katou, and Deepa Narayan, “The Role of HR in Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: The Case of Indian Pharmaceutical Firms,” Multinational Business Review 17, no. 2 (July 1, 2009).

3. Ibid.

4. Eric Bellman and Jackie Range, “Merger, Indian Style: Buy a Brand, Leave It Alone,” Wall Street Journal–Europe, March 22, 2008, A9.

5. Carly Chynoweth, “Dare to Try, the Indian Way: The Takeover of British Companies by Tata, the Asian Conglomerate, Provides Useful Lessons for Both Sides,” The Sunday Times, April 17, 2011, 1.

6. Ruth David, “Tata Acquires Euro Steelmaker Corus,” Forbes.com, October 22, 2006, www.forbes.com/2006/10/22/tata-corus-mna-biz-cx_rd_1022corus.html.

7. Communicaid Press Release, 2007, www.communicaid.com/news.php?newsId=76.

8. “Ratan Tata Hits Out at Corus, JLR Managers for Not Walking Extra Mile,” The Economic Times, May 21, 2011, http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2011–05–21/news/29568738_1_jlr-scunthorpe-corus.

9. Tor Ching Li, “Nippon Sheet Glass CEO Stresses Need for Clarity—Ensuring Understanding Is Key for a Company with Different Cultures,” Wall Street Journal–Managing in Asia, April 6, 2009, 20.

10. Josephine Moulds, “Stuart Chambers Quits Nippon Sheet Glass on Finding He’s ‘Not Japanese’,” The Telegraph, August 26, 2009, www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/industry/6094612/Stuart-Chambers-quits-Nippon-Sheet-Glass-on-finding-hes-not-Japanese.html.

11. Martin Fackler, “Japanese Bank Merger Plan Draws Support—UFJ-Mitsubishi Tokyo Deal Is Expected to Break Mold By Making Business Sense,” Wall Street Journal–Europe, July 15, 2004, M1.

12. Makoto Miyazaki, “Mizuho’s Balancing Act: Megabank’s Shakeup Could Hinge on Personnel Issues,” Yomiuri Shimbun, May 25, 2011, www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/business/T110524005737.htm.

13. Atsuko Fukase, “New CEO, New Mizuho Culture,” Wall Street Journal–Asia, June 23, 2011, 22, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304657804576401482167239952.html.

14. P. C. Haspeslagh and D. B. Jemison, Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value through Corporate Renewal (New York: Free Press, 1991).

15. Ven Ram, “Managing Asia: Former Standard Chartered Executive’s Credo—Acquisition Taught Lessons in Bridging Bank Cultures,” Wall Street Journal—Asia, May 4, 2009, 24.

16. Indranil Roy and George S. Hallenbeck, “Asia 2.0: Leading the Next Wave of Growth in Asia,” The Korn/Ferry Institute, December 2010, 8, www.kornferryinstitute.com/files/pdf1/Asia2.0.pdf.