CHAPTER FIVE

Getting It Right Before You Begin

Many companies stumble into mergers and acquisitions (M&A) before they are ready, resulting in botched deals or expensive and chaotic acquisitions. Companies can do several things to prepare themselves before they go down the M&A path. The first thing to do is to use our debt-equity framework to figure out whether the company should be considering M&A. A system should be put in place to methodically track and screen potential M&A targets. Building an acquisition factory focused on smaller deals can increase the chances of success. Understanding whether the company can shape industry dynamics using M&A will be an important consideration. Finally, a company should not be shy about surrounding itself with expertise to support the deal.

The seeds of a successful merger or acquisition are planted early, long before executives zero in on a target company or make an offer.

The failure rate of mergers is high. Our research indicates that 29 percent of mergers result in an increase in aggregate profitability. According to one A.T. Kearney study that measured long-term market capitalization trends of companies involved in mergers, slightly less than half of all M&A deals create value.

The companies that do succeed usually have a framework in place that signals when they should consider mergers, helps identify and track targets early on, and guides executives through the deal itself once it materializes. We believe M&A should be planned and considered. They should never be opportunistic.

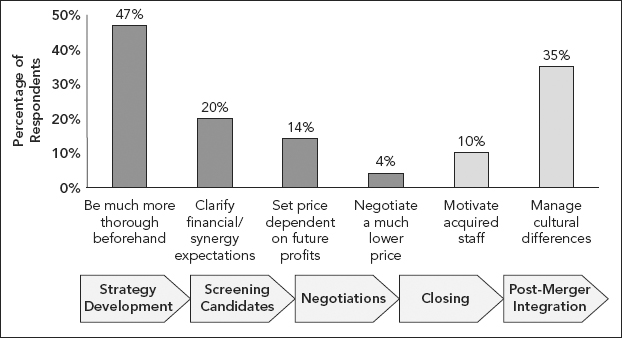

One of the biggest drivers of M&A success is an up-front strategy. We conducted a survey of M&A deals that worked and asked what factors contributed to their success: 47 percent of respondents said success hinged on being “much more thorough beforehand.” By comparison, 4 percent rated “negotiating a much lower price” as a factor behind success (see Figure 5.1). Getting it right early on is one of the two most important parts of the game; the other is the ability to integrate the M&A successfully.

Our analysis shows that many Asian companies are well-placed to achieve steady inorganic growth through M&A. Many opportunities are available in the wake of the global financial crisis and as economic activities shift from the developed Western economies to the emerging Asian countries. Asian companies are in a strong position to capitalize on this situation. Few Asian companies, however, have the processes in place to map out and execute planned M&A. Asian executives should take several key pre-merger steps to ensure the best deals get done (see Figure 5.2).

Leaders need to put a framework in place to determine whether M&A is right for their company, create a mechanism to track and screen candidates methodically, and determine which of several merger strategies will best achieve their goals and build expertise in that area. Finally, they need to conduct a deeper-than-normal due diligence, which we’ll cover in the following chapter.

STEP 1: A FRAMEWORK HELPS FORWARD PLANNING

When the leaders of most Asian companies sit down each year to come up with their forecasts and budgets, they typically focus on organic growth. Executives think about new sales points, new products, and new target markets. Inorganic growth is rarely part of the agenda during their annual planning cycle. Our research shows that M&A can play a key role in maintaining a company’s growth momentum. Companies that fail to put M&A on their agenda risk missing out on this important opportunity. If you want to grow ahead of the industry, M&A have to be part of the plan.

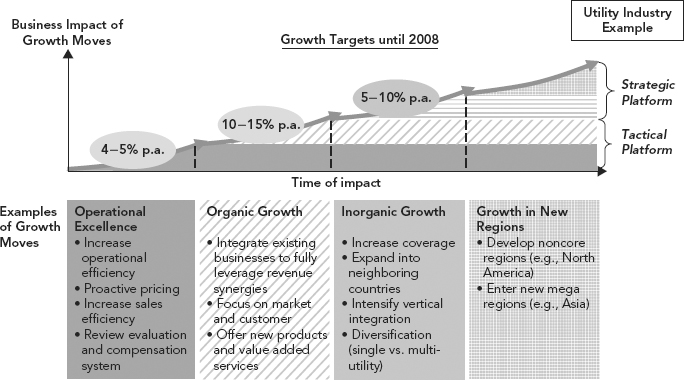

Consider the example in Figure 5.3, from a utility industry manufacturing company. The growth targets laid out for this particular company indicate that inorganic growth could meet or beat the company’s projected organic growth plans.

In Asia, corporate leaders typically think about M&A only after an investment banker has thrown an opportunistic deal their way. Too often, executives wake up in the morning, see a good deal, and think, “We should grab it.” We think that’s a mistake.

We advocate a more methodical approach. A.T. Kearney has developed a framework for clients that allows them to pinpoint where their company sits on the M&A spectrum at any time and signals what they should do: whether they should buy, whether they should sell out, or whether they need to stabilize before making any more moves.

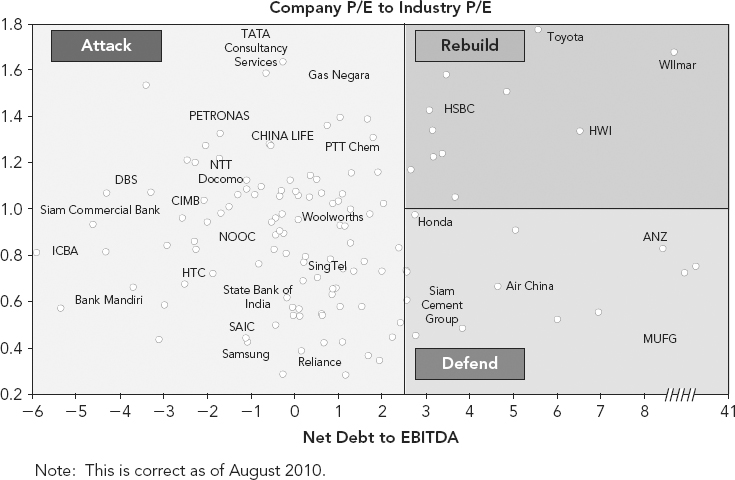

Our framework compares the ratio of a company’s net debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) to the ratio of its price-earnings multiple to the rest of its industry. In other words, we analyze how leveraged a company is and whether the company can use its stock as currency to fund its acquisition drive. Using these data, we generate a matrix that indicates whether a company should attack, rebuild, or defend.

The attack stance is reserved for companies with access to liquidity and limited debt. These companies are in a position to leverage their strong balance sheet and a rising market cap to pursue M&A. Rebuilding the organization is for safe-haven companies with limited ability to exploit market opportunities. Their focus is on strengthening their operational performance and cost position. Companies that get defensive do so because they are the most vulnerable to hostile takeovers. The best strategy for these companies is to pursue “friendly” buyers to divest equity stakes to guard against hostile takeovers.

We ran the top Asian companies through our framework and mapped out where they should be (see Figure 5.4). Our analysis highlighted several Asian companies that seemed well-placed to make some aggressive moves: Reliance, Petronas, SingTel, Tata Consultancy Services, and NTT Docomo fall firmly into the “attack” position on our matrix.

SingTel has implemented a series of M&A deals as market entry strategies in countries such as Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, India, and Pakistan. It pushed for entry into the African telecom market via its interests in Bharti Airtel. SingTel had announced in 2010 that it was on the lookout for more acquisitions, but given the limited opportunities relative to what it was willing to pay for, subsequently decided to return part of its cash hoard to shareholders as a special dividend.

Reliance Industries is also on the move. The Indian company has a sizeable presence in the refining and petrochemical businesses, including the world’s largest refinery complex at Jamnagar. A few years ago, Reliance made inroads into the upstream oil and gas segment and identified it as an area of growth. The company went on to buy the U.S. shale assets of Pioneer Natural Resources, Atlas Energy, and Carrizo Oil & Gas for $3 billion in 2010.

Reliance could take advantage of the current situation to enhance its presence in the upstream business outside India and add to its recent acquisitions. The company could also acquire downstream assets outside India to provide a channel for its refinery products. This strategy could help secure future entry into the more profitable upstream segment of the respective countries. Reliance could also make acquisitions in relevant parts of the chemical business that would allow it to become a price setter in a commodity environment. It attempted to do this with its bid on the petrochemical company LyondellBasell (which would have created the world’s largest petrochemical company ahead of BASF and Dow Chemical Company), but the bid was rejected.

Industry experts predict China’s airline industry is set for another round of consolidation, and could move toward the emergence of a mega-carrier that could compete with global giants such as British Airways or United.1 This could put Air China in “defend” mode. After a previous wave of consolidation in 2010, when China Eastern Airlines took control of Shanghai Airlines Co., and Air China acquired Shenzhen Airlines, China Airlines, China Eastern Airlines, and China Southern Airlines emerged as the country’s top three carriers. Air China, the country’s flagship, was left vulnerable as a result of high oil prices, rising interest rates, and its acquisition, which pushed its gearing high and its share price low. The company had raised its stake in Shenzhen Airlines to 51 percent from 25 percent in 2010, a move that boosted net income that year, but by 2011, its outlook had dimmed, and in May it announced that first-quarter profits were down 23 percent from a year before. It forecast that full-year profits would fall below that of 2010.

Air China should take care to recognize its defensive position if competitors, such as China Eastern Airlines, do aspire to giant status.

HSBC fell into the “rebuild” section of our matrix. Recent news reflects our analysis: In May 2011, the bank announced it plans to sell businesses and exit retail banking in markets where it doesn’t have scale. The bank shares reported lackluster first-quarter results that showed rising costs and flat revenue.2

A framework such as this is an important tool in today’s competitive market. Companies that are aware of where they sit on a matrix such as this one can plan ahead better. Armed with this kind of knowledge, executives can embed the M&A option into their annual planning cycle.

We believe that companies should run a regular health check to determine whether they should be in attack or defend mode to augment or protect their growth. It’s not enough to map out new products and marketing strategies each year. It’s important to clarify strategy for inorganic growth, too. The realization that you should be looking to buy—or are likely to be bought—should never come out of the blue.

We used this matrix as part of strategic work we did for an Asian downstream gas utility. We looked at where the company was and decided it needed to go upstream. The first thing we did was clear up its debt position. The company replaced its debt with low-cost funding and did a rights issue to build some cash. We used our matrix to map its position against global and regional industry players. This exercise signaled that our client should be on the attack and highlighted a number of acquisition targets that fell into the defend quadrant.

We are looking aggressively at gas assets upstream to target for acquisition. In many cases, these are small companies that do exploration work, or large companies such as Shell or British Petroleum (BP) that are offloading assets in parts of the world where our client can do well. We didn’t come across these prospective deals by chance. Instead, we discovered them because we’d created a matrix of key competitors and industry players and tracked them for nearly a year.

STEP 2: METHODICAL TRACKING AND SCREENING UNDERPIN SUCCESSFUL M&A

Every CEO or CFO in Asia is being pestered by investment bankers with deal books that lack imagination. Bankers and lawyers are constantly bringing ideas—good, bad, and ugly—to senior management. It’s hard to separate the so-so ideas from the great ones unless you have a clear strategy.

Once a company has figured out where it sits on the M&A spectrum, the next step is to develop a sound target assessment framework to track and screen candidates. M&A should be about planned acquisitions. This is the fundamental difference between companies that succeed at M&A and those that fail. Top acquirers set M&A objectives, constantly monitor the market for potential M&A opportunities, and execute the plan quickly when such opportunities arise.

A target assessment framework should be based on three core criteria: strategic, organizational, and financial fits. Companies need to look for candidates that fulfill strategic and synergy requirements, including products, technologies, and markets that complement or augment their own. Financial fit is crucial. Acquirers need to assess the target company’s price, debt structure, and profit picture, and see how it impacts their own balance sheet. Companies shouldn’t take on something they can’t handle. With organizational fit, a company must gauge how easily a candidate can be integrated. Nationality, leadership style, and the degree of centralization of the target operation can impact a merger.

Armed with these criteria, companies on “M&A watch” should generate a list of a group of companies they’d like to acquire and list the reasons and rationale for each. This framework should be able to filter candidates by quantitative metrics, such as price, and should detail the risks associated with each potential acquisition. Risks could include concern over whether the target company can achieve its growth targets, for example, or improve profit margins. If a company is tracking these potential targets systematically over time, executives should be able to reduce the risk, gauge the best price, and zero in on companies with the best strategic fit.

Consider the work we did for an Asian investment fund that wanted to enter the region’s banking sector. We helped that client create a short list of 10 banks that we tracked for four years. Over that period, the fund took a stake in five of those banks when it gauged the price, timing, and risk levels were right.

Companies that have built M&A into their annual planning cycle and have the discipline and process in place to track their candidates are in a strong position: When the target becomes available, they know how much they’d like to pay for it and have offset much of the risk that can undermine a typical acquisition.

The Asian fund, for example, mitigated the risk inherent in two deals thanks to our tracking system. The fund was considering a stake in a global bank, but the asking price seemed steep. The bank’s cost/income ratio was high, and though the bank’s executives insisted they could lower it, it wasn’t clear if they could achieve their goals. We advised our client to track the bank for six quarters, to see if they could deliver. They did. The client felt assured the stake was worth the price, and the deal went ahead.

In another instance, the fund was eying an Indonesian bank that wanted to diversify its corporate-focused business by expanding into consumer banking. After tracking the company for several years, we felt it had managed the transition badly. The consumer banking heads weren’t up to par and branch performance was poor. The acquiring fund put together a team of bankers with global experience to deploy to the Indonesian bank’s consumer business, and it moved ahead with the deal.

For each element of risk, companies who take a methodical approach to M&A can work out a mitigation plan. Patience and discipline help ensure the target is right, the price is right, and the level of risk is low.

STEP 3: CHOOSE YOUR MODEL: CLASSIC M&A VERSUS THE ACQUISITION FACTORY

Companies use two major M&A strategies to boost inorganic growth: classic M&A, which entail a large, one-off transformative deal; and the buy-and-build approach, where companies set up an in-house “acquisition factory,” generating growth through a higher number of smaller deals. Here, the buyer focuses on improving the bottom-line performance of a growing pool of acquired companies.

Classic M&A are about getting a big bang for a big buck. This is historically how deals were done. The Daimler-Chrysler merger, the Royal Dutch-Shell deal, and AOL’s acquisition of Time Warner are all textbook examples of transformative, classic M&A.

Today, however, more companies are taking the buy-and-build approach. These kinds of deals are less dramatic but less risky, too. Big, weighty mergers have proven hard to pull off. Creating value by merging two behemoths is difficult. Prominent failures of classic M&A, including Daimler and Chrysler, Time Warner and AOL, Adidas and Salomon Sports, and Siemens and Nixdorf underscore the pitfalls. Typically, the larger the deal, the tougher the challenges; the larger the parties, the higher the organizational complexity and the stronger the corporate culture of each party. Money and executive attention are focused toward managing a big deal, integrating a complex organization, and capturing synergies, and are diverted away from markets and customers, thus hampering profitable growth. Besides, regulators don’t take a kind view when one Goliath suddenly rules the market.

Many companies shy away from M&A because they believe it’s going to be an all-consuming, transformative undertaking. It doesn’t have to be. We believe that the buy-and-build approach offers a more sustainable route to growth and market leadership. It’s easier to accelerate growth by using a serial, standardized acquisition factory strategy to generate a series of frequent, smaller deals that don’t strain the entire operation.

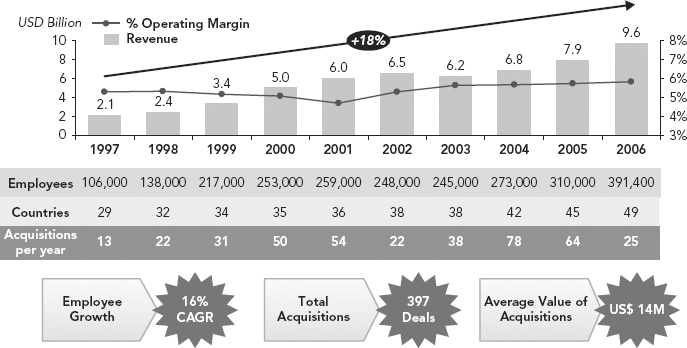

A services company that A.T. Kearney worked with (see Figure 5.5) did an astonishing 397 small deals, worth an average of $14 million each, over 10 years. The company’s revenue grew on a compounded annual growth rate of 19 percent over the 10-year period, while maintaining solid profitability. To be sure, this was a large corporation with a big budget. In some sectors and some countries, serial deals are often small, ranging from $1.5 million to $5.8 million.

The acquisition factory angle is still below the radar screen of many Asian executives, but this strategy provides many benefits: profitable growth, superior value creation, and market leadership in a far shorter time and at reduced risk, especially in industries in the opening and scale phases of the consolidation race.

As first movers, companies operating an acquisition factory can shape the consolidation of their industry and realize organic growth at the same time. Successful operators identify favorable market conditions, such as the availability of small acquisition targets in a fragmented industry, and confirm the target fits with their own strategy and business model.

Companies that run acquisition factories follow three simple principles:

- Leverage the relatively lower enterprise value (lower multiples) of smaller companies.

- Focus on shaping the acquired business to the core business model even if it leads to a limited loss of revenue.

- Improve performance throughout the acquired company in all functions, particularly by leveraging scale and centralizing most overhead functions as well as by leveraging best practices in the other functions.

Acquisition factories create value by applying an efficient serial acquisition process while improving mainly the bottom-line performance of the acquired business. The result is a significantly higher valuation multiple with the integrated businesses compared to their stand-alone valuation. Consider the following case study: A company with sales of $1.4 million and an earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) margin of 24 percent is acquired for $2 million, which reflects an EBIT multiple “as acquired” of around six. Post-acquisition, the company focuses on its more profitable core competencies and sales drop to $1.2 million, yet the EBIT margin rises to 43 percent. Combined with active performance improvement, this transaction created value in the range of 50 to 150 percent, which yielded an “integrated-company” multiple of about 10 and an enterprise value of $5.2 million.

Successful acquisition factories keep busy. Over a period of 5 to 10 years, they may do tens or hundreds of deals. Accordingly, they need a dedicated organizational entity and ongoing resources and capabilities for target search, acquisition, and integration. The factory organization and the company as a whole benefit from the focus on small, hidden champions as opposed to large-scale blockbusters or mega-deals. The benefits of focusing on smaller companies occur throughout and after the acquisition process.

The pre-acquisition and transaction phases, for example, are typically quicker and require fewer resources when dealing with smaller companies. Target selection and evaluation criteria are clear. Bidder competition is reduced and the target company is usually in the weaker bargaining position.

Smaller companies with few or simple products are less complex. That means due diligence teams have less to examine and integration can take place more rapidly. Acquisition and integration risks are typically lower and spread more broadly.

Value generation, meanwhile, often exceeds industry performance. Over the past 10 years, the 25 most active acquirers in the A.T. Kearney merger endgames database consistently outperformed the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Index by double the growth rates. Our merger endgames database includes more than 13,000 M&A that have taken place over the past decade.

First movers who make several acquisitions each year and integrate them rapidly can instantly enhance their market presence. Leaders who shape a consolidating industry can quickly gain market leadership and overwhelm competitors.

Acquisition Factory Winners Offer Insight into Strategy

Oracle’s CEO Larry Ellison was once quoted in the New York Times as stating, “It’s crazy to say you will only grow through innovation.” It is no secret that Oracle is consolidating the information technology (IT) industry by buying software rather than developing programs internally. Since 2005, Oracle has acquired more than 50 companies; although some deals are high profile, including the acquisitions of Sun, PeopleSoft, and Hyperion, most are under $1 billion. In 2009, despite the recession, Oracle spent $1.2 billion on three acquisitions, aside from the Sun deal. Oracle’s revenues doubled to $23 billion between 2005 and 2009, and maintained operating profits at around 50 percent.

Success stories of companies operating an acquisition factory can be found across industries and countries. Copenhagen-based Integrated Service Solutions, Inc. (ISS) is another interesting example.

ISS is one of the world’s largest facility management service providers, with market presence in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Australia. The Danish company employs more than 400,000 people and serves more than 100,000 business-to-business (B2B) and public sector customers in 50 countries. ISS’s services include shop floor and office cleaning, maintenance, catering, and security. In many markets, ISS faces strong competition due to low entry barriers in cleaning and related services. Since personnel expenses are the primary cost driver, competitors undercutting minimum wages and pursuing questionable labor practices are key challenges for ISS.

Foreseeing the global trend of outsourcing facility services to external providers, ISS started its acquisition factory in 1997. It initially targeted companies that were in or close to its core business of facilities cleaning, and later turned to more diversified areas such as catering and security.

ISS’s strategy aimed to build a full-service network and increase customer value by offering a one-stop, integrated offering for all relevant facility services. Its centralized customer relationship management enabled increased service quality and streamlined processes. The strategy enabled ISS to expand regionally, gaining access to overseas markets. The company acquired more than 450 small firms, increasing sales to more than $11 billion. Most acquisitions had revenues of fewer than $19 million when they were taken over. ISS made two large-scale acquisitions: Abilis in France in 1999, and Tempo in Australia in 2006.

With its acquisition factory, ISS consolidated the market substantially and continues to focus on small acquisitions to minimize transaction and integration risks and leverage local market knowledge.

The Key Elements of a Successful Acquisition Factory

Out of the many cases of successful acquisition factories A.T. Kearney has tracked, we have extracted three key factors for success (see Figure 5.6):

FIGURE 5.6 A Consistent Consolidation Approach Is Vital for Business Success

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

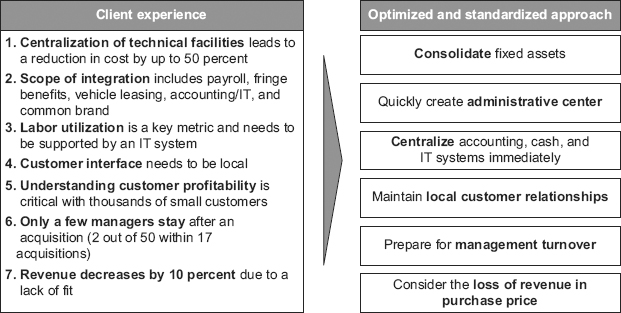

Companies can capture synergies and upgrade performance by centralizing, consolidating, and instituting initiatives such as better labor utilization. Another execution element may be to outsource noncore activities, accepting a loss in revenues. However, integration teams should focus on cost synergies and bottom-line activities to create value and on actions that enable profitable growth, by setting clear priorities for short-term growth and by strengthening the sales and marketing function. These measures include maintaining local customer interfaces and preparing for management turnover, through non-competition clauses.

Companies across all industries can learn from the systematic and efficient approach underlying an acquisition factory. At the right time and with careful strategic alignment, this industrial process approach to M&A produces profitable growth and value generation faster and with less risk than other strategies, resulting in industry leadership. However, we recommend keeping large M&A opportunities and organic growth moves in mind as well. Companies can combine these strategies to maintain their growth momentum under changing market and economic conditions.

Asian Industries Where Acquisition Factories Would Work Well

An acquisition factory is most useful to companies in fragmented industries where plenty of small competitors exist and buying opportunities abound. That’s what makes this strategy so compelling for Asia, where many companies operate in markets that have yet to go through consolidation.

Asia’s IT, retail, and telecommunications industries, for example, offer up many opportunities. Though early waves of M&A by the likes of SingTel have sewn up the obvious, major deals in the region, many telecommunications providers are snapping up smaller service providers and applications and content companies. Large, organized retailers around Asia are mopping up smaller players in a bid to boost growth in a low-margin industry. India’s IT services and IT hardware industries are fragmented, and deal opportunities abound. We are seeing a huge amount of M&A in this sector and expect more to come.

The commodity, agriculture, and food industries in Asia are ripe for serial deals. Little consolidation has occurred here and these industries are fragmented across the entire region. Indeed, many of our Asian commodity clients are working fast to snap up controlling stakes in downstream operations and competitors.

It’s an active industry. Hong Kong–headquartered, Singapore-listed Noble Group has been aggressively using M&A to transform itself from a supplier of raw materials and commodities into a diversified commodities company with stakes in a range of upstream energy and agricultural operations. Since 2007, the company has made six acquisitions and bought stakes in another six companies.

In 2009 and 2010, Noble bought stakes in Gloucester Coal, Blackwood Corp, and East Energy Resources, all Australian coal mining companies. Noble spent $950 million in 2010 to buy two Brazilian sugar cane and ethanol plants.

The consolidation trend in Asia’s commodities industry is expected to gain momentum. Noble, with its strong balance sheet, will continue to be an active player. Singapore-listed Olam International is also in M&A mode. Olam, like competitor Noble, a supply chain manager, announced several deals in 2010 in sugar, timber, fertilizer, and palm oil.

Another competitor, Wilmar International, has slipped into rebuild mode, according to our M&A framework. Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil trader, has been expanding quickly through M&A into ventures in sugar, palm oil, and other edible oils over the past few years. However, when we put Wilmar through our M&A matrix, the company appears in the rebuild position. The company’s financials deteriorated as it took on more debt to fund its M&A push, and its gearing ratio, which measures net debt to EBITDA, jumped from 1.7 times in 2009 to 5.5 times a year later. Stock analysts still like the company despite its increased leverage because its earnings prospects and credit facilities remain in good stead. But Wilmar’s slide down our matrix illustrates how important it is for companies in M&A mode to put a framework such as this in place, especially when other competitors are in attack mode.

STEP 4: SURROUND YOURSELF WITH EXPERTS

Ensuring that an acquisition is a good fit, not just on paper but as an integrated business, demands more than traditional financial due diligence; it requires a detailed value assessment. We call this a pre-assessment or improved due diligence. It takes place before a memo of understanding is signed and includes an examination of operational and management issues and risks. The insights gained are used to value the target, communicate to the board of directors, create a bidding strategy, plan negotiations, and accelerate the integration of the target company.

This early analysis provides a comprehensive perspective of the acquisition’s potential to create lasting shareholder value, and should influence how the market reacts to the acquisition announcement.

To get beyond the numbers and to challenge traditional assumptions about risk and value, winners pull together expert internal and externalresources that understand base business value and growth and can evaluate cost and revenue synergies.

For example, as a spreadsheet exercise, valuing a target’s base business can be straightforward. What acquirers often miss in their number-crunching process, however, is spotting problems in the target’s base business. These are usually not apparent from routine inspections of publicly available documents and will not be readily disclosed by the target company.

Another common mistake is failing to assess the target’s future growth rate and profitability and then neglecting to “sanity check” the findings against changing conditions in the macroeconomic, foreign exchange, and competitive environments. Forecasting an unrealistic growth rate for the target can have dire consequences for its valuation. If the base business is overvalued by 20 percent, an accurate evaluation of potential synergies will be of little comfort.

One way to manage these issues is to reach out to experts who have experience in working through this type of maze. Interviews with third-party industry or trade experts, customers, or suppliers will help if they can be done discreetly and out of public view. These people should be able to offer objective information about the quality of the target’s business, its executive talent and workforce, and its processes and products. For example, if a target company has a poor history of bringing successful products to market, the acquirer has the right to be skeptical of its positive claims about an upcoming product launch. If the company has a history of investing less in research and development (R&D), physical capital, or maintenance, the acquisition business case should anticipate and plan for increased investment in these areas. This will ensure reliable product supply and head off sudden unexpected increases in operating costs.

In evaluating cost and revenue synergies, many companies struggle with striking the right balance between the two. They place too much emphasis on cost synergies and ignore those that will point to future growth, or they overestimate growth potential and miss the short-term value that comes from improving efficiency. Analyzing synergies beyond financial statements is complex: Opportunities can cross functions, product families, and processes, but sorting through the complexity is worth the effort. An acquisition that gives appropriate weight to cost and growth synergies is more likely to succeed.

Again, for this effort, the top acquirers call on experts who have experience in helping companies identify and realize cost and revenue synergies, and navigate the legal and regulatory requirements needed to get the deal done.

A company considering M&A should build a team of experts that includes bankers, consultants, lawyers, accountants, and tax and regulatory experts. Investment bankers have a large role to play. Investment banks can provide specialized industry knowledge and contacts, and they can help sellers shop the company and assist buyers with valuation and negotiation strategy. They can help companies raise the capital they need to fund the purchase, by underwriting a debt or share issue or by arranging a private placement.

Accountants and tax experts play a critical role in performing financial due diligence, preparing fund flow statements, and working capital analysis, and advising on the tax structure and tax planning for the merged entity. They play a key role in the post-merger integration of the acquired business. Lawyers perform legal due diligence (LDD), create the legal documents that underpin the transaction, and assist negotiations of the terms of the deal.

Investment bankers, lawyers, and tax specialists are often called transaction advisors; they lend technical assistance leading up to the deal. Sometimes, these experts may overlook or underestimate the problems of post-merger integration; their job is to get the deal done. Most transaction advisors are paid on a contingency fee basis tied to the value of the deal. Though they remain as professional and objective as possible, they are often decidedly optimistic about the synergies of the two companies.3

Merger consultants are typically hired to provide unbiased analysis, benchmark organizational processes against a range of best practices, and provide big-picture perspective. Consultants track, screen, and select candidates, conduct due diligence, and analyze strategic fit; they can validate future growth rates of acquisition candidates, assess revenue and cost synergies, and help buyers unlock value by identifying areas within operations that could be streamlined or restructured. Consultants stay on to see the entire process through, working with the newly merged company through the entire integration process. After closing a deal, a company such as A.T. Kearney helps with integration, aligning cost synergies and promoting a fast and complete implementation of turnover strategies to ensure value capture. Comprehensive merger management support, from finding the right deal to making it work, is crucial in a world where most M&A fail to deliver the returns expected by executives and shareholders.

Winners make sure they tap their own team of internal experts in identifying and realizing cost and revenue synergies. Sales, marketing, and operations people should always be part of the value assessment because they are typically charged with, and held accountable for, integrating the two companies after the deal is signed.

Sun Microsystems does this well. Sun involves its sales and marketing team at the beginning of every potential acquisition to analyze the target’s products. The team explores the possible risks related to the products, including their success rate to date, projected growth in customer demand, “fit” with other products in Sun’s portfolio, and the likelihood that the products will enable Sun to expand its presence in desirable geographic, technology, or industrial markets.

By assessing potential synergies beforehand, a buyer can quantify the likely costs (expenses and capital) of implementing the acquisition and estimate the time it might take to realize the benefits. Both will influence how much the acquirer should pay for the target. With today’s constant refrain of “know what you are getting into” from investors, this value assessment will help identify the target’s viable potential. Essentially, it offers insight on the true net value of the deal, which confers an advantage at the negotiation table.

PLAN EARLY, THINK SMALL: THE RISK-AVERSE ROUTE TO SUCCESS

In short, it’s all about getting organized. Corporate leaders who know their own mind and put inorganic growth on their annual planning agenda and mechanisms in place to track potential prey methodically will have the upper hand. Companies that plan to do many small deals will achieve steadier growth with lower risk than those that opt for the classic “big bang for a big buck” M&A. And the more you do, the better you get at it. Companies across Asia should consider doing a few small transactions to understand the landscape, learn how to do deals, and understand the complexities of integration. This will allow them to get bigger and bolder with their inorganic growth plans, without taking on too much risk.

PREPARING FOR A DEAL

Getting it right before you begin goes a long way to ensuring success in any merger or acquisition. Here are five things to think about before embarking on the hunt for a target:

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney white papers and documents were used as background material in writing this chapter: “Impact of Crisis,” by Naveen Menon, a partner and head of the firm’s Asia Telecom practice; Kiran Karunakaran, a manager in the firm’s Australia practice, supplied the original Attack-Rebuild-Defend framework that was modified for this book; “Build Your Own Acquisition Factory,” by Jürgen Rothenbücher, a partner and head of the firm’s strategy practice in Europe, Martin Handschuh, a partner and member of the firm’s utility practice in Europe, Sandra Niewiem, a consultant and member of the firm’s strategy practice in Europe, and Michael Maxelon, an alumnus of the firm who acts as the spokesman of the board at SWK Netze, a utility company, in Krefeld; “Deal Making—Now Is as Good a Time as Any,” by Vikram Chakravarty, a partner and head of the strategy and corporate finance practice in Asia, Karambir Anand, a consultant in the Singapore office, and Rizal Paramarta, a consultant in the Jakarta office; “Mergers and Acquisitions: Reducing M&A Risk through Improved Due Diligence,” Strategy & Leadership 32, no. 2 (2004), by Jeffery S. Perry and Thomas Herd, both A.T. Kearney alumni.

Notes

1. Keith Wallis, “Mainland Mega-Carrier Could Emerge Amid Consolidation,” The South China Morning Post, March 11, 2011, 1.

2. Margot Patrick and Fiona Law, “HSBC To Cut Costs, Sell Businesses in New Strategy,” Wall Street Journal, May 11, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20110511–708804.html.

3. Anthony F. Buono, “Consulting to Integrate Mergers and Acquisitions,” in L. Greiner & F. Poulfelt, The Contemporary Consultant: Insights from World Experts (Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western, 2005), 229–249.