CHAPTER SEVEN

A Guide to Successful Post-Merger Integration

A large percentage of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) fail because the post-merger integration (PMI) process is mishandled. Successful integrations are about speed, leadership, communication, risk, and cultural management. Establishing a proper PMI team, with three important building blocks—merger management, value capture, and merger enablement—is important. A central program management office with the backing of senior shareholders and management needs to manage and drive the merger. SWAT teams must be formed to identify and deliver the synergies that have been identified as part of the merger proposition, with the full involvement of the eventual business line managers. Finally, key enablers such as information technology (IT) and human resources (HR) need to be aligned to ensure the company has the right technology and capabilities to take it forward.

After the deal has been sealed, the hard work begins. Integrating two companies is difficult work. This is the make-or-break juncture, and the odds are stacked against success.

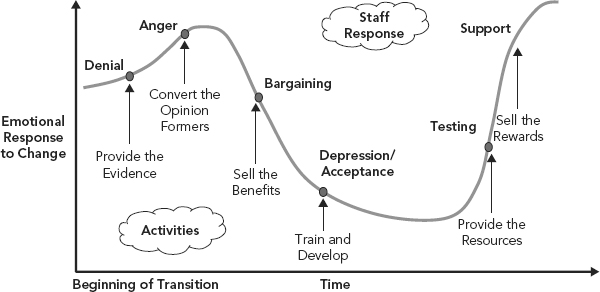

Few mergers create value. Our research shows that in Asia, only one-quarter of M&A deliver the expected benefits. Poor communication, unclear expectations, a muddled post-merger structure, lack of leadership, poor planning, and lack of momentum are often to blame (see Figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1 Problems Identified in Post-Merger Integration

Source: Global Merger Integration Survey; A.T. Kearney analysis.

The success or failure of a merger can be judged in many ways. Some companies look at how well their people work together, whether they integrated the processes smoothly, or whether they managed to acquire or launch a new product or cut some costs out of the operation. We think this is a narrow view of merger activities, and focusing exclusively on these activities can destroy value in the long term. Executives who undertake a merger must take a holistic approach to value creation; value can come out of or be derailed by soft issues, such as culture, and be driven by hard areas, such as direct earnings before interest, tax, and depreciation (EBITD) improvement, revenue upswing, and cost reduction. The success of a merger reflects the sum of all the parts, and each must be given due time and attention during the integration process.

We do not think Asian companies are more likely to face challenges in integration post-merger and acquisition compared to companies from the West. We do think, however, that as Asian companies are newer to the M&A game compared to their Western counterparts, they are probably less familiar with the challenges of PMI and with some of the tools and approaches for integration. In addition, Asian companies are probably less likely to look externally for professional help in these activities, preferring to resolve the issues on their own. Asian executives must develop a good, clear understanding of the PMI process if they want to emerge as winners in Asia’s merger endgame.

MERGER INTEGRATION OVERVIEW: THE KEY PILLARS OF A SOLID POST-MERGER PLAN

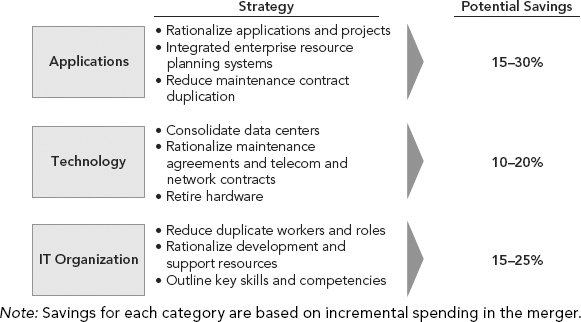

Integration doesn’t happen by itself. You need to plan every step of the process. All too often, companies don’t place enough emphasis on proper PMI. These companies buy another company, make some effort to merge production or back-office staff, and then hope for the best. The difference between those who succeed and those who fail comes down to how they manage the process. It always pays to look at what the winners have done. We’ve worked with a multitude of companies that have pulled off M&A, and we have distilled nine of the core best practices that drove these successful integrations. These are shown in Figure 7.2.

FIGURE 7.2 Successful Mergers and Acquisitions Consistently Exhibit “Best Practices” That Can Be Applied to Guide Value Creation

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

Establish a Sense of Urgency

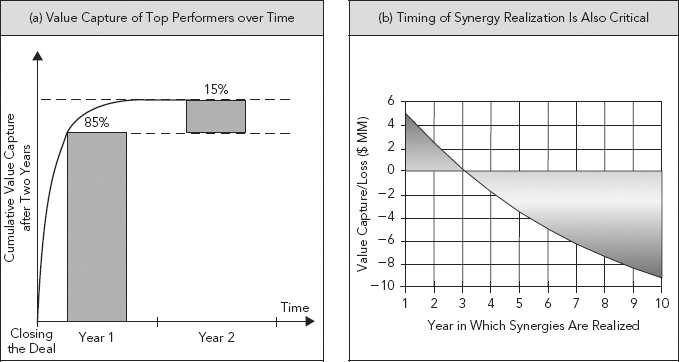

Time is of the essence in a merger or acquisition. A.T. Kearney studies show that 80 percent of the value of synergies is captured in the first year (see Figure 7.3). Little is achieved beyond that. Miss that 12-month window, and the value equation is largely gone. Creating a sense of urgency is the most vital part of the post-merger plan.

FIGURE 7.3 Key to Achieving Targeted Benefits Is Speed and Sense of Urgency

Source: A.T. Kearney’s Global PMI Survey; Mark L. Sirower, The Synergy Trap (New York: The Free Press, 1997). Calculated based on a $10 million acquisition premium, representing 50 percent of market value.

The winners work hard to light this fire well before the legal close of the deal. These companies create teams across multiple functions to plan for integration before legal day one and work with independent consultants to set up a clean room to analyze data they can’t share before the deal is legally closed. Using those data, the consultants help identify and quantify the synergies achievable by the companies and create a plan that the companies can launch on day one after the merger to capture the synergies. The cross-functional teams create a 100-day plan that outlines the key areas of integration, maps out the deliverables, states who is accountable for each item, and creates a system to track the benefits and highlight bottlenecks. These companies know who’s going to do what, where, and when to create value before day one dawns for the merged entity.

Select Leadership Quickly

We believe that a large-scale, transformative integration requires a Churchillian leader who knows what the company is shooting for and will go for it at all costs. Any large reorganization and change-management exercise needs a strong leader to champion the process. We encourage companies to decide on the chief executive officer (CEO) before the legal close. Early on, who’s in charge must be clear.

The CEO-designate can move quickly to interview candidates from both organizations and settle decisions on the next layer of leadership even before day one. The roles within the first tier of management should be resolved and communicated to the entire organization by the end of the first week. Quickly selecting the leadership team provides clarity, unity, and purpose. The chief financial officer (CFO), chief investment officer (CIO), and head of HR are critical to the success of the merger.

These decisions, however, are tough: Two people are doing the same job at the two entities, and a decision between them must be made. The CEO shouldn’t just divvy up these senior roles between the two companies, giving the CFO to one, for example, and HR to another. The new entity will be better served by taking the best person for the role. It helps to bring in a neutral party, such as an HR consultant, to assess the candidates and assist the CEO-designate in making a nonpartisan decision.

Sustain Open, Frequent, and Timely Communication

Communication is critical throughout the integration process. A merger can cause anxiety for multiple stakeholders, including the staff, shareholders, suppliers, consumers, and clients. A steady flow of information eliminates uncertainty, and misinformation that can plague a merger or acquisition. The merger office must take a proactive approach and address issues before they arise. We advise clients to be honest about job losses or let staff know when job decisions will be announced.

Management must also pay attention to the blogosphere. Sources from inside and outside the company will blog about everything from job losses to plant closures, and it’s often a mix of accurate information and mere speculation. In our experience, the best way to combat this is to release as much information as you can throughout the process and provide staff with a timeline of decisions on these key issues. If a blog speculates that a certain plant will close, refer to a timeline and say, for example, three plants are under review, but the other 18 are not. Then state when the decision will be made. Letting people know when they will find out what their future holds can help manage anxiety.

Winning companies typically have a day one communication plan that includes a conference call or e-mail conversation with staff on the legal merger’s first day, a 1-800 number that allows staff to get answers to critical questions they or their clients may have, and a staff intranet that includes information about how the changes affect jobs, reporting lines, and each business unit’s future. A good communication plan should include a schedule of town hall meetings or conference calls with the new entity’s leadership and an integration newsletter that goes out by mail and on the staff intranet to keep employees in the loop. Encouraging dialogue bridges differences in corporate or national culture; these can often beset a merger.

Focus Explicitly on Customers and Channel Partners

In a merger, people frequently take their eyes off the ball, and it’s easy to become focused on internal issues, such as “Will I have a job?,” “Who will my boss be?,” or “How do we get this system or that process to work after the merger?” A properly structured PMI plan will keep a company firmly focused on its customers. This is a critical time for customers and suppliers, too. Customers will be worried about disruption to supply, change in sales and supply processes, whether the products they are comfortable with will be eliminated, and whether the sales guy they worked with will be changed. This is a period when competitors know you are the most vulnerable, and they will take advantage of the situation and steal your customers. We frequently see competitors spreading fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) in customers’ minds, speculating, for example, that products will be phased out or not supported in the future.

Before day one of the merger, winners typically put together a jointly developed customer retention plan that focuses on keeping the lines of communication open. This plan kicks into action before day one, as it will involve the current team of salespeople and executives reassuring their respective customers that their welfare and interest will be covered. Once day one comes around, the plan will typically include visits from the newly merged entity’s CEO and top executives to key customers within the first week to reassure them nothing will change or it will change for the better. Without a strong customer focus, the entire merger could become an exercise in futility: Concerned about the future of their business relationship or the ability of the newly merged company to meet their orders or service their account, customers are likely to start exploring back-up options if the phone goes silent during a large transition.

Establish a Strong Integration Structure

A well-organized merger is put into effect by a solid, well-organized team. Key to this is a central program management office (PMO), which coordinates the entire effort, and a series of PMI teams, which execute the many initiatives mapped out by the PMO. Engaging the best people to carry out these roles is critical. Typically, a mix of consultants and in-house staff runs the PMO. The employees selected for this must have strong organizational capabilities and a powerful enough personality and presence to get people on board and motivate them to deliver on time. A PMO should stay in place for a year or more, and the staff selected to do this job must stay focused on integration until the end of the entire process.

To do its job, a PMO must have a strong mandate, clear authority, and the support of top leadership. Underneath the PMO is a set of integration teams that come from every business unit and work stream. An effective PMO has to reach every part of the organization. Companies that have executed successful M&A tend to put this defined, well-resourced integration structure in place for 60 days before the legal merger and keep it on board until the job is done.

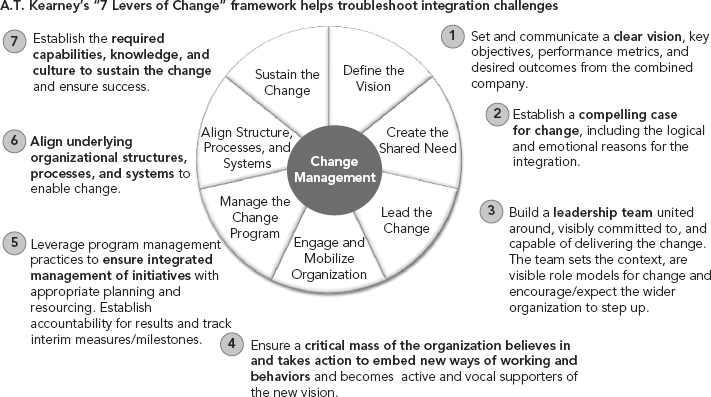

Manage Risks Rigorously

Companies need to keep a close eye on a set of indicators aligned to issues that can threaten to derail a merger. We recommend a series of proven reporting tools, which we’ll explain later in this chapter, that identify, track, and prioritize risks. The key here is communication: The PMO and the steering committee need to stay on top of where each synergy capture team is and what bottlenecks need to be removed. Risks can be mitigated before they blow up if everyone is aware of what’s going on. Figure 7.4 illustrates the levers of change we rely on to ensure a smooth integration. The biggest risks are that high-value staff will walk out, top customers will leave, staff morale and motivation will spiral downward, and the newly enlarged company will fail to capture the full value of the merger exercise. Getting on top of these risks early—preferably before they crop up—is key. Prevention is the best cure.

Address Cultural Issues Proactively

Many differences in corporate culture and organizational culture can impact value creation: Some companies have flat structures, reward individual initiative, and focus strongly on staff, believing growth will follow the natural productivity of well-motivated employees; others are hierarchical, encourage process-oriented behavior, and focus strongly on customers. We’ll get into this in more detail in Chapter 8, which is all about why culture matters in a merger or acquisition. Culture clashes—between companies with different corporate cultures or between staff of companies from different countries with different national cultures—can mire integration. Winning companies that have chalked up successful mergers conduct a cultural audit or assessment to understand the differences and create a strategy to bridge these gaps and harmonize the organization.

Establish Clear Goals and Manage Expectations

Setting clear, aggressive targets on where and how to capture synergy—including how much is expected and by when—takes you a long way toward achieving those goals. Integration teams and business managers can better focus if they have a clear map in hand and benchmarks to reach.

Create and Follow a Solid Merger Integration Plan

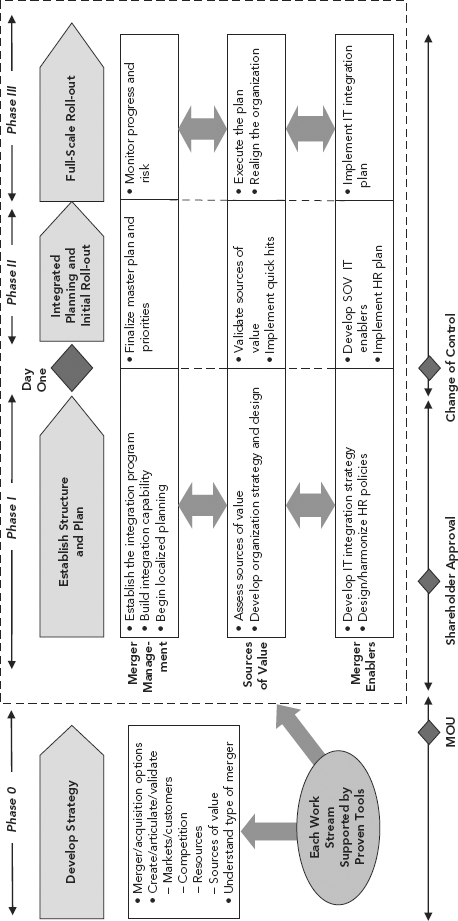

A.T. Kearney has a specific merger integration framework (see Figure 7.5) that helps establish a clear structure and plan for every step of the process. The three critical pieces to phase one of any integration are the following:

Let’s detail each one of these pieces.

MERGER MANAGEMENT: THE KEYS TO SUCCESS

Mastering the integration process is a critical success factor in capturing merger value. Most M&A fail because of the same set of consistent factors that relate to poor execution rather than strategic rationale. Almost all of the classic problems can be sidestepped with detailed planning. An integration exercise that’s shaped by a clear set of guiding principles, backed by a solid merger-management structure, and run using tested tools and techniques will succeed.

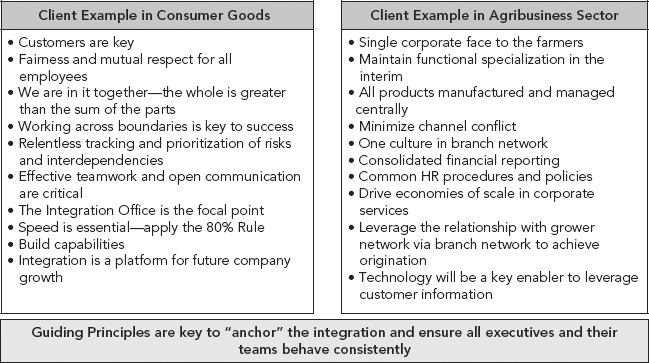

Guiding Principles of Integration

A focused, organized, and well-run integration starts from the top. Before the ball gets rolling and the planning gets underway, the CEO needs to create a set of guiding principles to anchor the entire integration process.

As soon as a company starts building up toward an acquisition, the CEO should spell out the rationale and reasons for the deal. The CEO might argue, for example, that the industry is getting competitive and the company needs to build scale or might argue that the acquisition target brings a set of customers or technology that will benefit the organization. These drivers can be tapped to form the basis of the guiding principles for managing the integration.

The set of guiding principles usually comprises 10 or so central points that focus on the key goals of the integration exercise and the process of integration itself. These points help set broad boundaries and goals and ensure executives and their teams behave consistently throughout the merger process. Each of the guiding principles has implications for the integration process and should drive the behavior of the combined entity.

One consumer goods company we worked with, for example, created a set of guiding principles that focused in equal parts on customers, staff, and the merger (see Figure 7.6). The first principle on their list was “Customers are key.” That had key implications for the company’s post-merger strategy. Sales teams, for example, would need to be quickly combined to minimize customer disruption. The consumer goods company’s guiding principles called for fairness and respect for all employees and went so far as to state, “We are in it together—the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.” That helped drive home the point that everyone would benefit from the merger and had a part to play.

The consumer goods company’s principles stated integration would be the platform for future company growth, and the integration office should be the focal point. This is a point many companies often miss: A well-organized integration leads to a successful merger, and winning companies create this house within a house to run the integration program. You must give the integration PMO the profile and authority it deserves; embedding this point in the principles that guide the exercise lends weight to that authority.

Some of the guiding principles could be operational in nature: The consumer goods company, for example, stated in its document that “speed is essential” and the PMO should “apply the 80 percent rule.” Experience shows that 80 percent of the value of a merger comes in the first year, so a lot of heavy lifting must be done during the first 12 months. Stating this as a core goal helps set expectations and direct the pace of work, key milestones, and staffing requirements needed to make it happen.

Setting Up a Structure

If a company’s leadership wants to achieve value out of a merger or acquisition, it has to recognize that integration is a full-time job. The CEO needs to set up an integration management office that operates as a house within the house, staff it with seasoned employees and bring in consultants with solid merger experience. This group of people holds everything together: It maps out the necessary changes, creates teams to put those changes into effect, and does what it takes to move the process.

The integration office, or PMO, should be composed of a mix of people from the acquiring and acquired companies. Below the PMO are the integration teams, which are divided into two streams: value capture SWAT teams and merger enablement teams. Value capture teams will pilot and implement initiatives to leverage synergies from the mergers; merger enablement teams—from groups such as IT, HR, legal and finance—will do the functional work needed to bring the two organizations together and support the synergy initiatives.

Some will work full-time in this role for a year or more until the integration is complete; others will pitch in part-time on top of their business-as-usual roles. The permanent program managers should be high-caliber people with a strong presence and excellent communication skills; they need to be able to unclog choke points, push integration teams that are behind schedule, get the attention of senior management, and escalate issues to the steering committee.

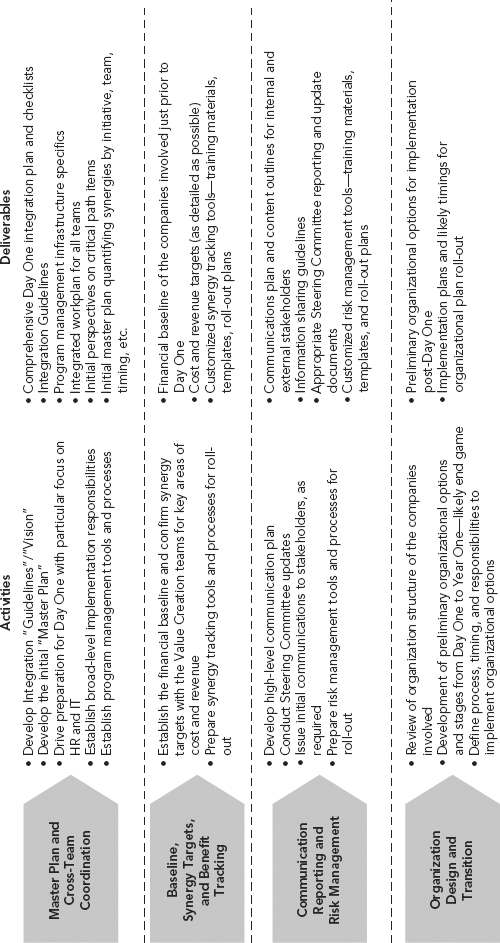

The foundation for this house is formed well before the deal’s legal close, and we talked earlier about consultants who help companies set up a clean room and create a 100-day plan to jump-start the merger. Armed with the 100-day plan, the PMO can build integration capability and do more detailed, localized planning for an integration master plan. That detailed master plan identifies sources of value capture (be it top line, cost reduction, or productivity gains), identifies teams responsible for different parts of the implementation, and maps out a timeline for their deliverables. It is critical to create a framework early that establishes the structure and plan that will ensure an acceleration of integration, post-day one (see Figure 7.7).

The next job of the PMO is to put together the integration teams. On day one, the synergy SWAT teams pilot new ideas, implement quick hits to capture those gains, and move on to longer-term projects outlined in the master plan. Piloting each initiative helps determine which practice gives the best result and gives key staff a chance at a dry run before rolling it out to the entire company.

When we worked on Sime Darby’s merger, for example, one of the key synergy initiatives was improving the yield of the palm oil trees (see sidebar at the end of this chapter). We put together a series of workshops with staff from all of the merged entities to share their processes and determine which was the best practice. The team picked a few hectares to test a range of initiatives, from the way they use fertilizers to how they harvest the fruit and maintain the fields around the trees. Team members had a chance to observe the results and familiarize their respective staff with the new processes before rolling it out companywide.

Each initiative is tracked. Each value capture team must document where the synergy will come from, how it will be measured, and what the baseline will be. Cost and revenue projections are worked into the master plan. The PMO creates a tracking system that maps when certain synergies will kick in and measures how much benefit and value it brings against what was expected. It is critical to be able to track and measure how much value has been captured as a result of the merger.

The PMO also acts as a focal point for all merger-related communications. It reports regularly to the steering committee, which reports to the shareholders. The integration team works with the press office to communicate with media, investors, and the internal HR team to create a flow of messages to the merged company’s employees. The PMO coordinates communication within the integration team and the value capture teams. Managing communication across multiple teams tasked with roles that are often interdependent is a critical job.

Another PMO role is risk management. During a merger, risks come from all sides: There’s a tendency to lose track of the customer, key staff may depart, and there’s the high-level risk that the merger may not deliver the originally anticipated value. Tensions are brought on by outside parties, such as labor unions, the government, or irate shareholders opposed to the deal. The press has its inevitable queries. The PMO has to deftly track and handle all of these issues without losing focus on integrating the two companies.

The other key role of the PMO is to help the HR department create a new organizational structure and map a transition strategy. The HR team typically takes ownership of this task and often works with an HR consulting firm. The PMO, however, will be a part of that team. The CEO and shareholders will quickly decide some of the big-picture issues, such as who will lead various functions and business units. Structuring the next layer down is a more detailed, complex piece of work that is one of the largest issues in any integration program. The HR integration team needs to map a new structure, including new functions and roles, and to decide who will fill each position.

Tools and Techniques for Merger Management

Coordinating the integration of two or more companies is an exercise in organization. The program managers need to coordinate a large number of integration teams whose projects are often interdependent while keeping all members on track and on time. A number of tools and techniques can keep all these teams focused and help senior executives understand what they need to do to clear any roadblocks along the way.

The first of these tools is the team charter, a one-page document written by each integration team to summarize its goals and initiatives. The charter outlines each team’s key objectives and defines its mandate, scope, targets, deliverables, and timing. It should pinpoint the risks and issues that need to be addressed and identify the potential decision the steering committee must make to help the team cross hurdles and meet goals. The charter makes sure each team is on the same page, working toward a common goal, with the support it needs from the leadership.

Another important tool is the synergy blueprint. This one-page document prepared by each value capture team provides more detail about the benefit initiative they are pursuing. It outlines the rationale and assumptions of each initiative, provides detail on critical milestones, and lays out a time frame in which the expected benefit will materialize. If the team is focused on procurement, for example, the synergy blueprint will lay out items such as the total combined spend of the two merged entities and then break these out by categories. The document might state, for example, that the team plans to renegotiate a supplier contract within three months and expects to bring costs down by 5 percent. The target date for the new pricing will be stated in the document, along with an estimate for total savings.

A third critical tool is the flash report. This is usually a weekly or bi-weekly update prepared by each integration team on key activities, achievements, and issues that need to be escalated to the PMO or the steering committee. The PMO consolidates all the individual flash reports and creates a summary for the steering committee to review. Depending on how fast the merger is moving, the PMO may present a written consolidated report once a week or present the update in a face-to-face meeting every two weeks. That consolidated report will detail how many teams are on track, which teams are falling behind, what issues are miring the process, and what needs to be done to mitigate those problems. This reporting system allows the PMO to stay on top of each cost reduction initiative and do what it takes to remove any roadblocks along the way.

Another set of tools provides stakeholders with a bird’s-eye view of the integration exercise and enables timely intervention to deal with issues as they arise. The first of these is the high-level master plan, a one-page high-level flight plan prepared by the PMO. It draws on each individual team charter and synergy blueprint and gives a snapshot of the entire integration program, including targets, milestones, major dates, decisions, and meetings required to facilitate these goals. It also delineates which projects are dependent on others and ensures those interdependencies are managed and communicated clearly.

The integrated master plan is a more detailed project plan that tracks the milestones and deliverables of all the integration teams. The individual integration plans put together by each team are rolled into this master plan, which tracks the totality of key tasks being pursued by all of the teams. This detailed map maintains the rigor and momentum of the program and ensures consistency in the overall integration plan. The master project plan is reconciled against the flash reports and is updated every two weeks.

Integration is nitty-gritty, detailed work. A good integration is backed by teams who execute against their charters and by a program management office that can track and manage the integration over a sustained period. If a company sets up a dedicated team, gives it the appropriate authority and oversight, and brings in some experts to bring experience and discipline to the exercise, it’s more likely to achieve the gains it anticipated at the start. If a merger is managed well, tangible numbers will come through the door.

SYNERGY VALUE CAPTURE: HOW TO GET IT RIGHT

A number of core areas can be tapped to unlock value in almost any integration. We typically focus on ways to rationalize assets and capital investment, improve operations productivity, and boost top-line growth. Figure 7.8 illustrates the synergies that were captured, post-merger, by one high-tech company we assisted.

You have to move fast to get it. Research shows that companies who have pulled off successful M&A capture 85 percent of the deal’s value in the first year. Setting the bar at the right level also helps. Shooting for targets you plan to exceed helps accelerate shareholder value creation. Be conservative about what you communicate to the market, but at the same time, set more aggressive internal targets. If a company states publicly that it plans to capture $500 million in synergies over two years but internally aims for $700 million in 18 months and meets that goal, it will win extra kudos from the market and investors. That scenario creates a strong upside for the company’s stock price. It’s always better to beat—not simply meet—what the street expects. The worst thing is to promise merger targets that can’t be met: The company’s shares could take an unnecessary beating if you appear to fall short of your goals.

By the time legal day one arrives, consultants and senior line managers should have analyzed and identified how much value they can create and detailed how and when those goals can be achieved. Shortly after day one, value capture teams need to test out those synergy assumptions and incorporate those initiatives into their synergy blueprint.

We recommend our clients use a prioritization matrix that maps the likely impact in terms of value against the ease of implementation. The teams can focus on some quick hard hits that bring value in the door by moving first on high-value initiatives that are easy to carry off. The matrix maps contingencies and clarifies which efforts can be undertaken only after one or two other initiatives have been played. It will show the core synergy areas that typically deliver value in a well-structured integration.

Operational Synergies

When two competing companies merge, they often overlap in geography, production, or distribution. Frequently, production and distribution facilities can be rationalized, cutting costs dramatically. Consolidating production plants impacts costs around salaries, depreciation of manufacturing assets, maintenance costs, and even property tax and insurance.

Core production and distribution facilities can be expanded to build a better economy of scale; transferring a larger portion of production to the lowest cost of the two companies’ facilities can add further value. Duplicate fixed assets, such as offices, branches, equipment, or trucks, can be reduced.

A merged company can find value by adopting the best practices of the two entities on everything from manufacturing and supply chain management to sales, IT, research and development (R&D), and accounting. A layperson might think that two competing companies in the same industry would operate similarly; the differences, however, are often surprising. Picking the most productive or cost-efficient method between the two and implementing it as the new standard can bring plenty of savings.

M&A often provide an opportunity to scale back future cash outlays for assets. Mergers typically create excess capacity that the company can grow into, reducing the need for much of the capital investment that either entity had previously planned.

Procurement is another area that offers value. The merged company can find quick cost savings by harmonizing prices, and the best price between two merging companies can be implemented for common purchases. The supplier base can be rationalized and consolidated, which increases purchase leverage. When two competing companies come together, the new, larger organization with higher volumes and a higher spend has much more muscle to negotiate better deals from suppliers.

The newly formed entity can achieve savings by consolidating office space and redundant roles in areas such as accounting, finance, marketing, engineering, IT, and legal and public affairs.

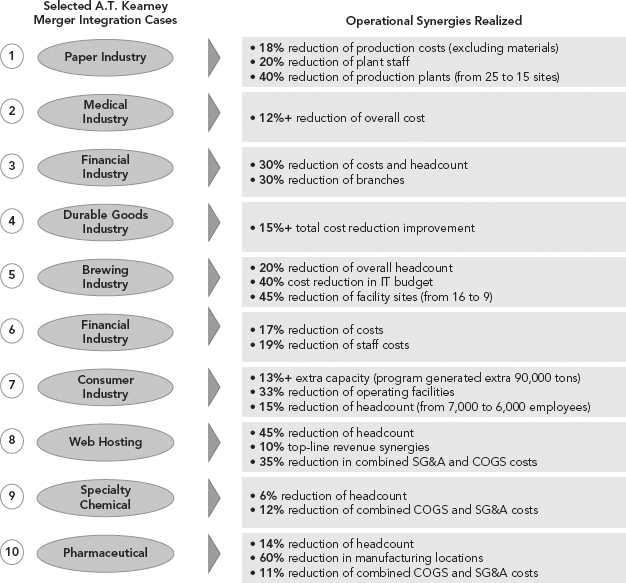

We tend to focus on operational synergies early and repeatedly have wrung value in mergers in a wide range of industries. Figure 7.9 highlights a wide array of cases that we have worked on in recent years.

FIGURE 7.9 Our Merger Integration Experience Indicates That Substantial Operational Synergies Can Be Realized in Any Industry

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

Top-Line Synergies

Companies can drive revenue synergies by integrating branches or channels, leveraging the new depth and breadth of the expanded product line, and cross-selling to each other’s customer base. A fuller product line will attract new customers who prefer to use fewer suppliers with a greater range of products. Brands can be bolstered by access to products that are superior or that weren’t part of its stable.

To unlock this core revenue synergy, a newly merged company must sort out its organizational structure to support its sales and marketing teams and take steps to empower its sales force. In many cases, merging organizations are unprepared for this. All too often, these companies let the opportunity to empower the sales force and drive improved performance slip away.

The sales team typically faces multiple challenges in a merger situation: There’s often a lack of systematic customer segmentation and a poor understanding of the needs of customers who are new to them. The sales force may have a limited understanding of the new product suites. Worse, the supporting systems and procedures to leverage leads for cross-selling are typically limited or lacking entirely.

These problems can be addressed by moving quickly to train sales staff to be conversationally competent across a broad range of product areas. A team of product specialists could be identified to offer assistance to sales staff during the early days, if the sales staff requires it. Creating financial incentives is important to motivate sales personnel to cross-sell the merged entity’s full suite of products. If it is in their interest to tap clients and move products that are new to them, the sales staff will do it.

The leadership of the merged company must work quickly to educate its newly combined sales force about its recently acquired brands and the profile and details of the new set of customers. If sales staff from either organization knows little about the customers or products that have come from the other side, they can’t do much to leverage new sales opportunities.

We worked on a merger in Singapore where one of the city-state’s top four banks bought a government-owned retail savings bank that had a 95 percent share of basic retail deposit products but few other product offerings. Cross-selling and retraining were two of the core synergy initiatives. The merger brought in more than $40 million in annual cost savings, with no staff layoffs or customer attrition. More than 1,000 of the acquired bank’s employees were offered specialized training and redeployed into productive jobs in the acquiring bank. It paid off: The acquiring bank enjoyed a strong upswing in profits after it began cross-selling its products to the retail savings bank’s customers. What’s more, the company’s share price rose fivefold after A.T. Kearney came on board to implement the integration program. That sharp rise illustrates how a focused, well-organized PMI program delivers value to shareholders and the acquiring company.

Asset and Capital Investment Rationalization

In a merger, opportunities will arise to sell duplicate factories or move production to the lower-cost facilities in the company’s newly broadened asset portfolio. As mentioned in Chapter 5, we often find, on closer inspection, that much can be done to improve productivity at existing facilities and postpone or cancel planned capital investment plans. All of this means significant savings to a merged entity.

Innovation Synergies

Product development and innovation is another area that offers value, provided key merger-related hurdles are removed. New R&D teams can crossbreed knowledge to create innovations and leverage competencies of the second entity to advance existing products. During a merger, it’s often how two newly merged entities can leverage each other’s product development capabilities. R&D can get bogged down by the absence of a budget, the approval process, and the governance structure in a merged entity: Product innovation may not be institutionalized, leaving research staff without funds, support, or direction. The combined companies may have yet to put the right incentives in place, such as key performance indicators (KPIs) or bonuses to motivate innovation.

A few key measures can unlock value from R&D. The heads of the respective research departments should be involved in merger planning and integration. If the research facility is located away from headquarters, leaders should bring key R&D people onsite as often as possible so they don’t feel disassociated from the integration process. The heads of research from both companies need to connect early if any synergy is going to come from this unit. Products can take years to develop and test; this particular stream needs to come together and come online early in the merger process.

Integration program managers should establish a direct linkage between the customer-facing sales teams and the product and development teams from both entities. The R&D units need to work with their counterparts from the acquired company and need to create products for new customers who might have different needs. The final step needed to jump-start post-merger innovation is to remove any organizational barriers that might slow development. These often include lack of incentives, lack of clarity around organizational reporting lines, and lack of connectivity or support around the two former entities’ IT systems.

MERGER ENABLEMENT: THE GLUE THAT HOLDS IT ALL TOGETHER

The HR and technology departments are the most critical levers for change in any merger or acquisition. HR and technology are high-risk, mission-critical areas that can facilitate a merger or wipe out value before the integration is complete. The ability of the leadership to provide HR and IT with the resources and mandate to transform their respective structures—and propel their constituents through a difficult transition—underpins the success of the entire venture.

Managing People

When a company sets out to buy another, it’s not focused on bricks and mortar; it’s acquiring human capital. People drive innovation, create brands, build client relationships, and push sales. A company’s performance hinges on the skills, expertise, knowledge, and motivation of its employees. The success of any merger or acquisition largely depends on how effectively organizational issues and human capital are managed. Here’s where an informed, organized, and merger-ready HR department comes in.

Before the merger occurs, HR needs to undertake a resources audit, figure out who adds value and where duplication exists, and map a new organizational structure. It needs to assemble a benefits package and retention strategy to ensure the most valuable resources stay on. One of the biggest risks in M&A is that the best employees will head for the door because they don’t want to deal with uncertainty or they believe they’re going to get a bad position in the new entity. To manage this risk, we provide a framework to our clients that identifies high-priority employees and categorizes each as a temporary or long-term asset to the company. Retention packages designed to keep these employees around ensures the merged companies capture the value of these key resources.

Employees might be classified as high-priority assets because they have a lot of retained knowledge about customers, the IT system, or the production process but aren’t viewed as long term because someone from the acquiring company will take over their role. Employees should be apprised of the situation and offered an attractive package to stay on for 12 months to transfer their knowledge. High-priority employees with a long-term future should be assured they play an important role and should be offered a retention package.

About 5 percent of employees will fall into these two categories. The rest need to be reassured, and that should happen through the PMO’s communication initiatives. Even if people are not losing their jobs, there’s a huge amount of tension that builds before a major event like a merger or acquisition. The ability to keep employees engaged during a transition is critical. We advise our clients to make sure they do right by the organization and by the people. The notion of treating people fairly is at the core of the communications strategy we create for the companies we work with. We always advise our clients to be direct and honest. Never lie. Don’t state the merger won’t result in job loss. Even if layoffs aren’t a major part of the value capture plan, some redundancies may occur. Be honest about job losses, if any are planned, or tell employees this issue is still being examined and state clearly when this announcement will be made.

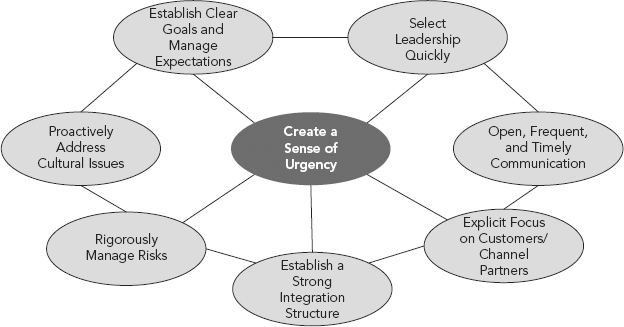

A merger is a time of anxiety for employees, and HR plays a critical role in guiding people from both organizations through the inevitable roller coaster of emotions that accompany an integration exercise. Many staff will go through a cycle of denial, anger, and depression that can be pushed to acceptance and support by a responsive HR team. HR leaders must explain the benefits of the integration to staff from both entities, equip them with the training they need to succeed in the new organization, and provide the resources and incentives to reach new performance goals (see Figure 7.10).

The other major human capital issue that can rock a merger is a clash between the corporate or national cultures inherent in the two organizations. The HR department of an acquiring organization and the PMO need to measure and map cultural gaps and create a strategy to bridge those differences before the merger takes place. (For a more detailed discussion on this, see Chapter 8.) HR can do plenty to break down barriers that might impede a timely integration: Informing staff of what’s going on, discussing problems, and involving staff in the process go a long way toward building acceptance, nurturing empowerment, and motivating employees.

Information Technology: The Anchor for Integration

IT plays a vital role in creating a smooth transition within merged companies and delivers quick, reliable value. A merger, however, could fail if poorly executed IT integrations bring sales and operations to a halt.

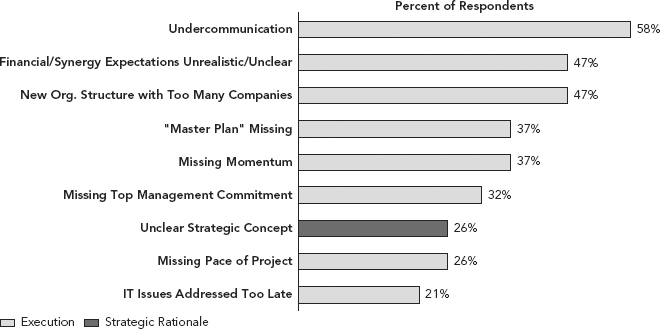

Merged firms will find they have similarities between their IT functions, even when few geographic, industry, or product overlaps exist. Reducing duplicate software applications and licenses, maintenance, and network contracts, and consolidating data centers can result in major savings. Organizational and support costs go down as duplicate applications and technologies are retired and as unneeded roles are eliminated and skills and competencies better defined. Companies can save 10–30 percent by reducing portfolios and outlining the skills and competencies needed for the future IT model.

PMI is the perfect time to save money by improving IT procurement contracts. A first post-merger step is to assess similar contracts within the new organization: Discrepancies in prices are a chance to reap concessions from vendors. The combination of existing contracts can lead to more volume savings, so reopening contract negotiations could be the right step. Figure 7.11 lays out several areas within IT that offer potential value during an integration.

IT enables other synergies. It’s the glue that binds the business together, integrating major business functions, improving communications, enhancing processes, and ensuring that customers receive uninterrupted service. This is vital: If customers walk out, the value of the merger evaporates into thin air.

The technology department builds the combined company’s long-term capabilities and its operational model. Once the short-term integration work is complete, IT can devote its energy to support the new company’s planned business growth. A cost-effective technology infrastructure is a prerequisite for success.

IT helps provide visibility during the merger integration, which is a period of uncertainty for those who work in the combining organizations. Reporting infrastructures, social networking, wikis, and dedicated portals can allow leadership to communicate plans and progress to the organization and halt the inevitable rumors. In this way, IT facilitates the integration of the companies, preserves employee morale, and ensures productivity in an otherwise turbulent environment.

An acquiring company can employ several different strategies when it comes to IT integration. Table 7.1 lays out five good options that work for different companies, depending on the style of management, financial position, and other circumstances.

TABLE 7.1 Five Approaches to IT Integration

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

| Approach | Description |

| 1. Loosely coupled | Remain separate and fragmented, and modify reporting for consolidation purposes. This approach is appropriate when companies are independent entities within a larger conglomerate, and most viable when extreme time pressure exists. |

| 2. Select one | From many IT setups, select the one that is most aligned with combined business strategy. This approach works best if there is significant discrepancy in sizes. It is the fastest method for reducing costs. The architecture direction defaults to Company X as a day one solution. |

| 3. Best of breed | Choose the best of available setups with an eye on architectural direction. This is the best approach in a large-scale “merger of equals” or with entities with different business models across the combined organization. It can be time-consuming but functional. |

| 4. Replace all | Phase out legacy systems and setups. This approach works best when point-specific solutions are poor in both companies and new software is easily integrated. It can be time-consuming in selection and implementation. |

| 5. Outsource | Spin out systems issues to a third party that is aligned with architectural direction. This approach is advantageous in mergers where there are large size discrepancies, repeated acquisitions, and poor internal IT skills. Here, “economies of learning” from several mergers reduce integration time. |

Our approach to integrating IT requires aligning IT with the merged company’s business strategy. We used this approach to help several companies save millions of dollars in IT costs while smoothing out often rocky post-merger transitions. The four key steps include the following:

Several companies have used our IT integration approach to generate great benefits from a merger or acquisition. After one global food and beverage company made its largest acquisition, its first move was to absorb more than 20 different IT operations into three regional IT setups. The company jump-started the integration by examining infrastructure, data center, and applications to design a new IT organization and find cost-cutting opportunities. It placed new governance structures to manage all ongoing IT integration efforts and created a two-year IT plan that outlined the organization, technology platforms, and budget for the department. IT operations costs were cut by 10–30 percent, leaving the company free to pursue its longer-term growth agenda. Another large European utility, which owned majority stakes in several utilities, had to combine diverse IT functions into a single IT organization. When the firm evaluated its options, including analyzing its current IT infrastructure and broader IT trends, it found it could save $135 million by standardizing its application portfolio, harmonizing business processes, improving service levels, and minimizing running costs.

THE POST-MERGER MUST-DO LIST

SIME DARBY MERGER SHOWS HOW POST-MERGER INTEGRATION, DONE WELL, CAN DELIVER QUICK VALUE

In 2007, Sime Darby, Golden Hope, and Kumpulan Guthrie merged to form the world’s largest palm oil plantation company. The merger helped consolidate Malaysia’s fragmented industry and delivered unprecedented value to the company’s shareholders.

Integrating these three large, publicly listed companies was a mammoth task, and A.T. Kearney was brought in to drive the synergy initiatives in the plantation business. According to briefings to analysts the enlarged company managed to implement 10 large-scale plantation synergy initiatives that delivered 160 million ringgit (RM) ($51 million) in earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) in 9M FY08. That figure was higher than the RM28 million ($9 million) boost that had been originally forecast. This merger illustrates how a well-planned and executed post-merger integration (PMI) program can unlock value quickly.

Malaysia’s agricultural sector was initially dominated by rubber plantations, which produced 50 percent of the world’s rubber output by 1921. Stiff competition prompted the government to look for ways to diversify its economy, and it settled on palm oil. Malaysia’s landscape and climate are perfectly suited to palm oil trees, which produce more oil for every hectare planted than any other competing vegetable oil crop. It’s one of the cheapest edible oils, and, by 1966, exports to Europe, India, and China turned Malaysia into the world’s largest palm oil producer. Palm oil is used as a cooking oil and as an ingredient in a wide range of downstream products, from chocolates to cosmetics to biofuel. By 2007, however, land-rich, lower-cost Indonesia surpassed Malaysia’s output and took the number one spot.

The government decided consolidation would give its highly fragmented palm sector a badly needed boost, and in 2007, three government-linked palm oil companies—Sime Darby, Kumpulan Guthrie, and Golden Hope—agreed to merge.

Guthrie was set up as a rubber plantation company in 1821; Golden Hope was set up in 1905 and Sime Darby in 1910. All three were taken over by the Malaysian government after independence. Despite their rich histories, each of these companies had gone into a slump and become somewhat bureaucratic.

Merging companies that had such storied legacies meant a lot of work had to be done to drive every joint decision. People who have worked for a lifetime in a historical company tend to feel that their way is the right way. Deciding which of the varied planting, fertilizing, and harvesting methods the new entity should adopt, for example, gave rise to emotional debates and heated exchanges. The decision to take Sime Darby’s name for the merged entity was painful for many employees of the other two companies.

We set up a joint A.T. Kearney-Sime Darby PMO, working with another external firm, which quickly created a day one action plan, created an integration structure below the office, including a set of synergy capture teams, compiled a set of team charters, and put together an integration master plan. The PMO put a set of synergy benefits tracking and reporting processes in place and set up a risk management program and a communication plan, targeting internal and external stakeholders.

Our first job was to validate some of the synergy targets that had been mapped before the merger. We created synergy capture teams to pilot these initiatives and drive consensus among the merged management about how best to reach these goals.

Leadership of the synergy capture teams was jointly held by the three merging companies, with each team led by a leader and supported by two sub-leaders from the other two companies. Care was taken to ensure team leadership was spread across the three companies, and that the team members respected the new team leaders.

One of our synergy initiatives was to adopt a standardized best-practice approach to estate management. Each company had its own agronomical and estate management practices, and each was determined to keep them. We went into minute detail to extract synergies: Dozens of policies ranging from how to prepare the land, how far apart to plant the trees, and when the fruit is ripe enough to harvest had to be aligned to smooth operations and deliver value. We even tested new ways to get workers to pick up loose fruit that drops off the palm bunches during harvesting.

Palm fruits, which are about five times the size of a peanut, grow in bunches slightly bigger than a basketball that weigh around 20 kilograms. These are cut by harvesters and fall up to 30 meters to the ground. Often, the super-ripe fruits, which are richest in oil, fall off the bunch before harvesting or break off the bunch and scatter as they hit the ground during the harvesting. The collection team, which typically gets paid by weight, often passes over the loose fruit because collecting the individual fruits is tedious, backbreaking work. Focusing on the fruit bunches is easier. Palm oil goes into everything from chocolate to shoe polish, and the best grade oil commands a higher price and, therefore, higher margins. The ripe loose fruit produces the most valuable oil, and the synergy capture team piloted a number of ideas to ensure these gems weren’t left on the forest floor. One idea was to make it easier for workers to collect loose fruit by giving them a long-handled tool for grabbing small kernels without bending over. Another initiative was to pay collectors based on the grade of fruit they brought in, not just on the weight.

Some of the meetings to decide on best practices for the merged company became heated and wound up in arbitration. A workshop run to determine the type of seeds the new enterprise should use, for example, ended in a deadlock. Most plantation companies produce their own seeds, which take years of R&D to develop. Selecting the winning seed was a touchy topic for these planters. Data-driven records were needed to decipher which firm’s seeds had proved the most productive after normalizing factors like soil quality, rainfall, etc.

Another big initiative was to consolidate over 20 different estates into 12 estates. By reducing the number of administrative staff, office expenses, and estate supervisors, the merged company saved money. We created a team to figure how to optimize mill capacity and routing. The new, larger network of mills and estates created an opportunity to re-route freshly picked fruit, reduce transit times, and get the palm fruits processed more quickly, which would lead to better quality oil. The teams leveraged the new scale of the company to renegotiate lower external transport costs.

Some of the other synergy initiatives the teams helped put in place included reducing fertilizer costs by moving to the lowest-cost suppliers and garnering discounts for higher volumes. The capture teams also reckoned they could leverage the scale of the combined company to reduce the cost of spare parts for its mills.

A.T. Kearney helped create clear implementation plans and identify which managers were accountable for each synergy initiative. We helped define KPIs, responsibilities, and targets for management’s top level to support the process. Finally, we helped design the incentive structure at all levels of the organization to motivate the employees to implement the improvement plans and back up the business strategy.

Investors got their money’s worth out of this integration. The shares of all three companies were trading around RM8.90 when they were delisted in November 2007, halfway through our transformation program. The shares of the expanded Sime Darby were relisted at RM11.20 less than one month later.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney white paper was used as background material in writing this chapter: “Make or Break: The Critical Role of IT in Post-Merger Integration,” by Sumit Chandra, Christian Hagen, Jason Miller, Tejal Thakkar, and Abha Thakker.