CHAPTER 6

The OSTP Obsession Continues

LONG BEFORE THE WORLD got shackled with the chains imposed by the pandemic, Washington, DC, was bustling with AI-related activities. In March of 2019, The Economist organized a conference on AI. It was strategically designed to announce the reappearance of artificial intelligence back at the national stage. The aftermath of the unexpected results of the 2016 elections had wiped out or steamrolled many initiatives. Those that survived went underground to try to take the pulse of the new administration before reemerging. Apparently, AI was one such initiative, and it had to wait for its turn behind other compelling priorities such as the coal, oil, and trucking industries. When it finally reemerged, it was brought back to life by a presidential directive signed by President Trump more than two years after he had assumed office. In February of 2019 the president signed the corresponding executive order.

The fact that it took the president two years to issue a directive that pretty much stated that America must maintain its AI leadership position was a testament to the complacency that surrounded America. As if it were something that America should have waited for two years, the power and potential of AI were ignored at the highest level, and when finally the president addressed the issue, it was too little, too late.

BETWEEN 2017 AND 2018

Besides hiding under the rock somewhere the entire 2017 and most of 2018, the OSTP did only two things. In May of 2018 it organized a conference to meet the industry, established yet another committee (known as the Select Committee on AI), and issued a memorandum on R&D budget priorities. For two years, the same two years when China developed AI at an incredible pace, the OSTP lost precious time to develop and implement an AI industrialization plan. For two years, the OSTP-led bureaucracy destroyed America's potential to move forward at the speed of relevance.

While the March 2019 conference was organized by The Economist, it was sponsored by Microsoft. It took place at the luxurious Four Seasons Hotel in Washington, DC. Under the exotic chandeliers and surrounded by art gallery–level artwork, the hotel projected power and prestige. Advertisement cards with Microsoft's name were neatly laid on the tables. Hundreds attended the conference. Excitement was in the air. Microsoft was launching a new AI business school, and the conference became the epitome of what was wrong with America's AI initiatives. Surrounded by commercial consultants wearing the cloak of professorship from top schools and staff of commercial sponsors, senior government officials appeared as the czars of AI. Short of being paraded around in a palanquin, the royal treatment the government officials received showed the symbiotic relationships that have become the symbol of why America lost its leadership position in AI.

THE EXECUTIVE ORDER AND PLAN WAS UPDATED

As the ideological debates raged and passions flared up across the country, the Trump administration needed to show progress.

On February 11, 2019, President Trump signed Executive Order 13859, which established the American Artificial Intelligence Initiative. This initiative broadened the scope of AI to the whole of government. And it greatly expanded the strategic responsibility of the OSTP. The OSTP observed that a lot of AI-related investment activity is happening in the industry, academia, and nonprofits; hence an update to its 2016 National AI R&D Strategic Plan was important.

Michael Kratsios signed the letter that introduced the updated plan. He wrote:

In August of 2018, the Administration directed the Select Committee on AI to refresh the 2016 National AI R&D Strategic Plan. This process began with the issuance of a Request for Information to solicit public input on ways that the strategy should be revised or improved. The responses to this RFI, as well as an independent agency review, informed this update to the Strategic Plan. (Trump 2019)

The RFI that he referred to received a total of 46 responses, where 2 came from IBM. The responses included 20 from associations, societies, trade, and consortiums; 1 from a major consulting firm (Accenture); 3 from large tech firms; 2 from small tech firms; 2 from semiconductor manufacturers; 4 from individuals; 6 from universities; 5 from think tanks; 2 from Fortune 500 firms; and 1 from a legal institute. Needless to say, the number of responses was disappointingly low. It was as if the nation had become indifferent to AI and its potential. No one cared. The confidence in progress was lost.

The health care sector was heavily represented by associations—including radiology, clinical, and other representative associations. But AI is not just for health care. There was no or little representation from the financial, insurance, or food sectors, pharmaceutical firms, consumer goods, marketing firms, sports, entertainment, energy, construction, travel, transportation, telecom, and many other industries. Once again, the level of engagement and representation from industry was minimal.

Of all the possible universities only six (Princeton, Caltech, University of California San Diego and University of Southern California [joint comment], UT Austin, and Indiana University) participated. That is about 0.48% of US News-recognized universities and colleges, or 0.15% of all registered universities and colleges in America.

Despite such a disappointing turnout, OSTP paid absolutely no attention to the fact that there was no engagement from a wide spectrum of American society, that those who participated did not answer all the questions, that many just paid lip service, and that no one criticized or disagreed.

Once again, the plan was validated based on negligible representation from America. The emperor stayed naked.

Once again, the solicitation turned out to be nothing more than a formality, a check the box, an insincere bureaucratic ritual.

Once again, the thinking was shaped by Big Tech and a handful of universities that likely had relationships with Big Tech.

Once again, societies and trade associations lined up to influence the so-called strategy—which was essentially “open up the bank.” Not an ounce of disagreement, no criticism, not even constructive feedback.

OSTP continued with its reckless posturing, which continued to hurt the American interests.

Granted, some technology and health care associations did claim to represent hundreds or even thousands of companies or individuals, but it is likely that those represented had no clue that the society of which they are a member is submitting comments on AI on their behalf.

It is hard to believe that Deloitte, PWC, Cap Gemini, Booz Allen, McKinsey, and other reputable consulting firms did not have any advice to offer. It is also not comprehensible that several emerging AI firms—such as DataRobot, Blue Prism, and UiPath—did not have any comments to give. It is hard to believe that the emerging government-focused AI firms such as NCI or Palantir did not want to share their thoughts about such an important area of American progress and future. The fact that Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan or Citibank or Procter & Gamble or Honeywell or General Dynamics did not have direct feedback showed that no real feedback was obtained. The reality is that either these firms did not know about the RFI or they simply did not consider the OSTP invitation credible and sincere or that their comments would make a difference. The fact that small and medium-sized companies from all sectors were not represented shows the shallowness of the effort. The most important strategy in the history of the country received no guidance or support from America. Why bother! They must have determined that nothing would change. If anything, this showed the mood of the country. No one really believed in the OSTP-led strategy. No one really cared. It was just another bureaucratic initiative—not something to get inspired by. There was no national awakening. There was no national commitment.

The responses to RFI had gone down from 150 (2016) to just 46 in 2019. Most of the comments from associations were valuable, although none challenged or criticized the OSTP plan. Accenture's Paul Daugherty, global chief technology and innovation officer, offered the following recommendation:

We encourage the Administration to focus on defining goals for investments made in AI, and in doing so, consider both the value and capabilities of AI. These five value levers are: Intelligent Automation, Enhanced Judgement, Enhanced Interaction, Intelligent Products and Enhanced Trust. A framework of five value levers can help prioritize quantifiable results and sustainable growth for AI R&D.

Due to the rapidly changing environment driven by emerging technologies as well as investments being driven in the private sector, we encourage the federal government to create a formal engagement strategy between the public and stakeholders to better identify and monitor investments, as well as anticipate risks and challenges in long-term R&D. The federal government would benefit from a formal advisory committee of stakeholders outside government, which would include industry, technical experts and consumer advocates. (Daugherty 2018)

In that above comment, Accenture was essentially pointing out that the investment goals remain undefined and hence inefficient allocation of capital can lead to waste, that quantifiable results matter, and that engagement outside the government is necessary. This comment captured what OSTP should have done but failed to do.

But none of that stopped OSTP from running around doing victory laps, celebrating some type of success. For five years of activities, what exactly did OSTP have to show for its efforts? A few conferences in luxurious hotels, a plan update composed of eight strategies, seven of which were left over from a previous plan, an unimpressive website, a few memberships in already developed international standards, over-obsession with governance-related fearmongering, and a few brag statements. That was the extent of the contribution made by the OSTP from an AI industrialization and adoption perspective.

With the newly launched AI Initiative, what was just an AI R&D and federal funding project would now become an AI national strategy. America just made its worst mistake in its AI journey. If America fails to recover from this mistake, decades from now when historians analyze America's decline and fall, they will point to this event as the primary reason behind the decline. This would be the parallel to the role of Rasputin in contributing to the credibility loss of the czarist government. An organization whose mission was to recommend R&D funding on science and technology was now running the national strategy of the country.

Most likely, President Trump did not know all the facts. Most likely, he sincerely believed in what he was being told. It was the responsibility of the OSTP to inform the president about the above facts.

It was OSTP that should have told the president the facts that only 46 responses have come for the RFI and that only about 100 people participated in the much-bragged 2018 conference. OSTP boasts that over 100 people (academics, government employees, industry professionals, and associations) attended the industry conference it organized in May of 2018. But remove the staff, the government employees, and the academics, and how many industry people would really have attended that conference? From how many industries? What were the qualifications of the people who attended, and what was their roles in their companies? The reality is that the OSTP never wanted to get real feedback. It was simply interested in one-way communication from a compliant audience whose role was to applaud and praise the OSTP. In return they would continue to receive fundings. The bank must stay open. It didn't matter if the nation goes down. It didn't matter that just about 100 people attended the industry conference on the biggest and most critical technological, scientific, and mathematical revolution in human civilization. But at least OSTP got the brag rights about the event.

THE 2019 UPDATE, A CLOSER LOOK

Integrating the RFI responses from 46 entities and based on the directive given by President Trump, a new plan appeared. This plan was not very different than the 2016 plan. The document began by a letter that begins with:

In his State of the Union address on February 5, 2019, President Trump stressed the importance of ensuring American leadership in the development of emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), that make up the Industries of the Future. (Trump 2019)

As a matter of fact, President Trump did not make any reference to emerging technologies or artificial intelligence in his February 5, 2019, speech. The closest his comment came to this topic was, “And I am eager to work with you on legislation to deliver new and important infrastructure investment, including investments in the cutting-edge industries of the future.” To turn this comment into some type of policy statement of the government is purely embellishment.

From the OSTP perspective, they then presented on what they considered their challenge:

The landscape for AI R&D is becoming increasingly complex, due to the significant investments that are being made by industry, academia, and nonprofit organizations. Additionally, AI advancements are progressing rapidly. The Federal Government must therefore continually reevaluate its priorities for AI R&D investments, to ensure that investments continue to advance the cutting edge of the field and are not unnecessarily duplicative of industry investments. (Trump 2019)

Note that the above statement refers to how they perceived their goal and challenge. It was to ensure that the federal government continues to invest in AI and does that in areas where there is no unnecessary duplication. While this was a respectable goal, the problem is that it is based on several assumptions.

First, it assumes that we are aware of not only how America is applying AI but also what is the best and most optimized application of AI across the US economy. This obviously requires having an industrialization perspective—which the OSTP did not have. Managed by scientists and technicians, OSTP was responding to the research needs of the US research community—and to some extent of Big Tech—and not to the industrialization needs of America.

Secondly it assumes that the investments made by the industry are in advanced technologies and not in technologies that are branded as AI but are really trivial, low-impact technologies.

Third, it assumes that diffusion of technology is happening and technology is being adopted.

Fourth, it assumes that the OSTP clearly knows how and in what areas non-government investment is transpiring.

Fifth, it assumes that there are no organizational constraints, change management challenges, and political considerations.

Sixth, it assumes that national knowledge and human capital are being developed and nurtured to take advantage of the investment.

Seventh, it assumes that there is a receptive and engaged population that is rapidly transforming innovations into practical applications.

None of that was included in the plan or even considered as variables that needed to be analyzed. The eight OSTP strategies turned out to be:

- Strategy 1: Make long-term investments in AI research;

- Strategy 2: Develop effective methods for human-AI collaboration;

- Strategy 3: Understand and address the ethical, legal, and societal implications of AI;

- Strategy 4: Ensure the safety and security of AI systems;

- Strategy 5: Develop shared public data sets and environments for AI training and testing;

- Strategy 6: Measure and evaluate AI technologies through standards and benchmarks;

- Strategy 7: Better understand the national AI R&D workforce needs; and

- Strategy 8: Expand public-private partnerships to accelerate advances in AI.

Strategy 8 was added as a new strategy. The RFI responses, as few as they were, suggested that OSTP takes a more proactive role in AI industrialization—which the OSTP probably translated as holding a few more conferences, wine-and-dine meetings, and issue more meaningless reports.

For the most part the plan seemed a self-affirming, self-praising, and self-directed plan—except it was hugely self-deceptive.

Making long-term investments in AI is not possible without truly understanding the sector-by-sector value chain needs of the entire economy. They cannot be deciphered without analyzing how sectors are being or will be redefined. They cannot be developed without understanding the impact of great-power competition, decoupling, a need to redesign American supply chains, economic performance expectations, or analyzing the various innovation trajectories and paths. Oblivious to all that, OSTP erected a plan that was based on the “field of dreams” thinking.

HISTORY BEGINS IN 2018—REALLY?

To praise their accomplishments of organizing summits and conferences, the OSTP published a document titled “American Artificial Intelligence Initiative: Year One Annual Report.” In that report, the OSTP bragged about its accomplishments.

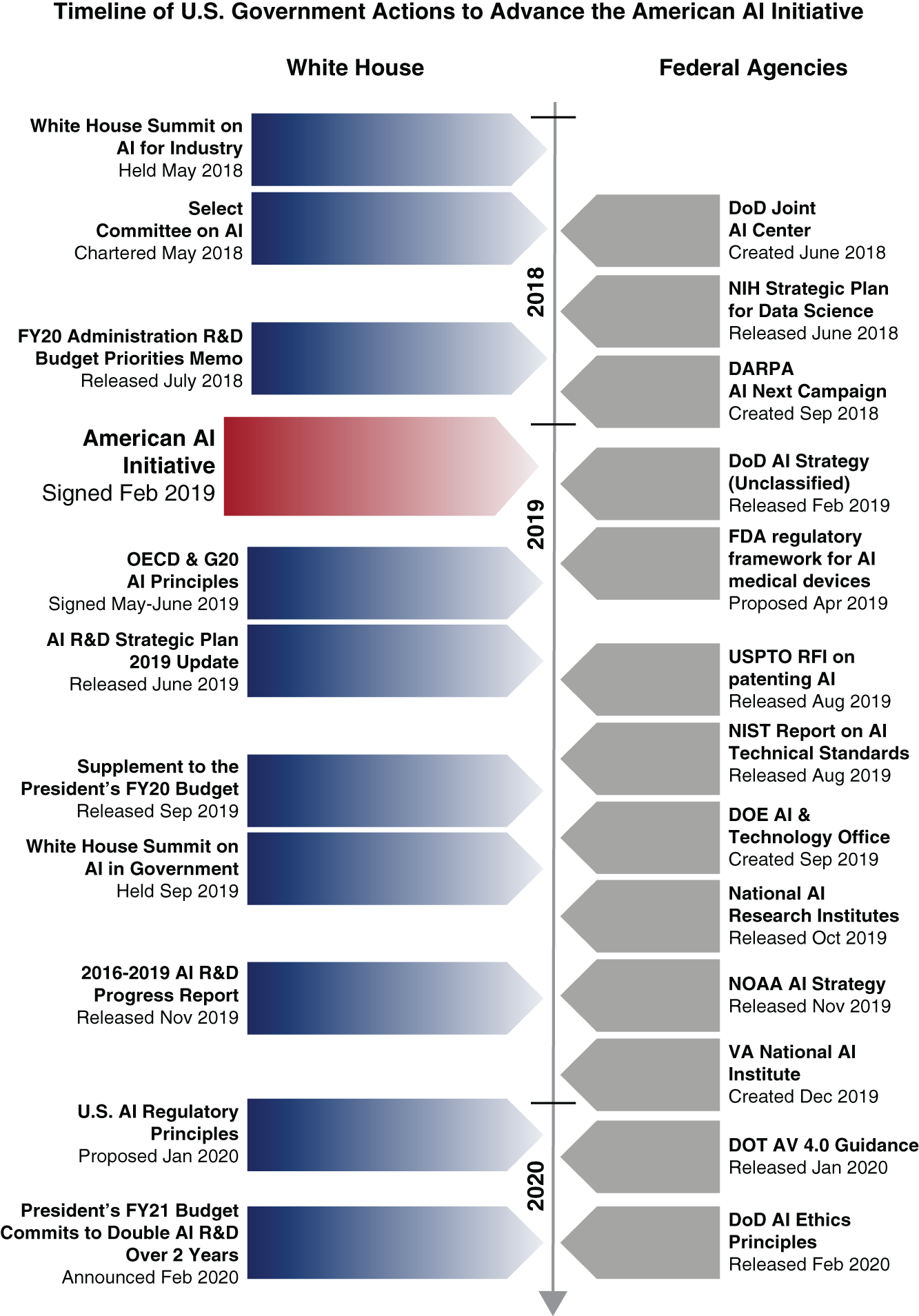

Based on our research, one of the most factually inaccurate and blatantly false claims was made when a diagram titled “Timeline of US Government Actions to Advance the American AI Initiative” started the timeline in May of 2018 (Figure 6.1). As we have discussed in the previous chapter, the AI initiative was well underway during the Obama administration, and it was incredible that the start time was depicted in May of 2018. The most likely reason for this intellectual amnesia is that the Obama-era AI initiative was rebranded as American AI Initiative and relaunched as that in 2018. Ironically, the 2018 initiative was based on the same drivers as before.

After two years of following the base plan that was established under the Obama administration (2016), the Trump White House needed to show progress, change, and movement. Hence, when the 2020 report card was issued, it rewrote the history and made May of 2018 as the starting point of AI in America. Never mind that in 2019, OSTP (along with several other working groups and committees) had issued a report titled “2016–2019 Progress Report: Artificial Intelligence R&D”—and the 2016 plan was done under the Obama administration.

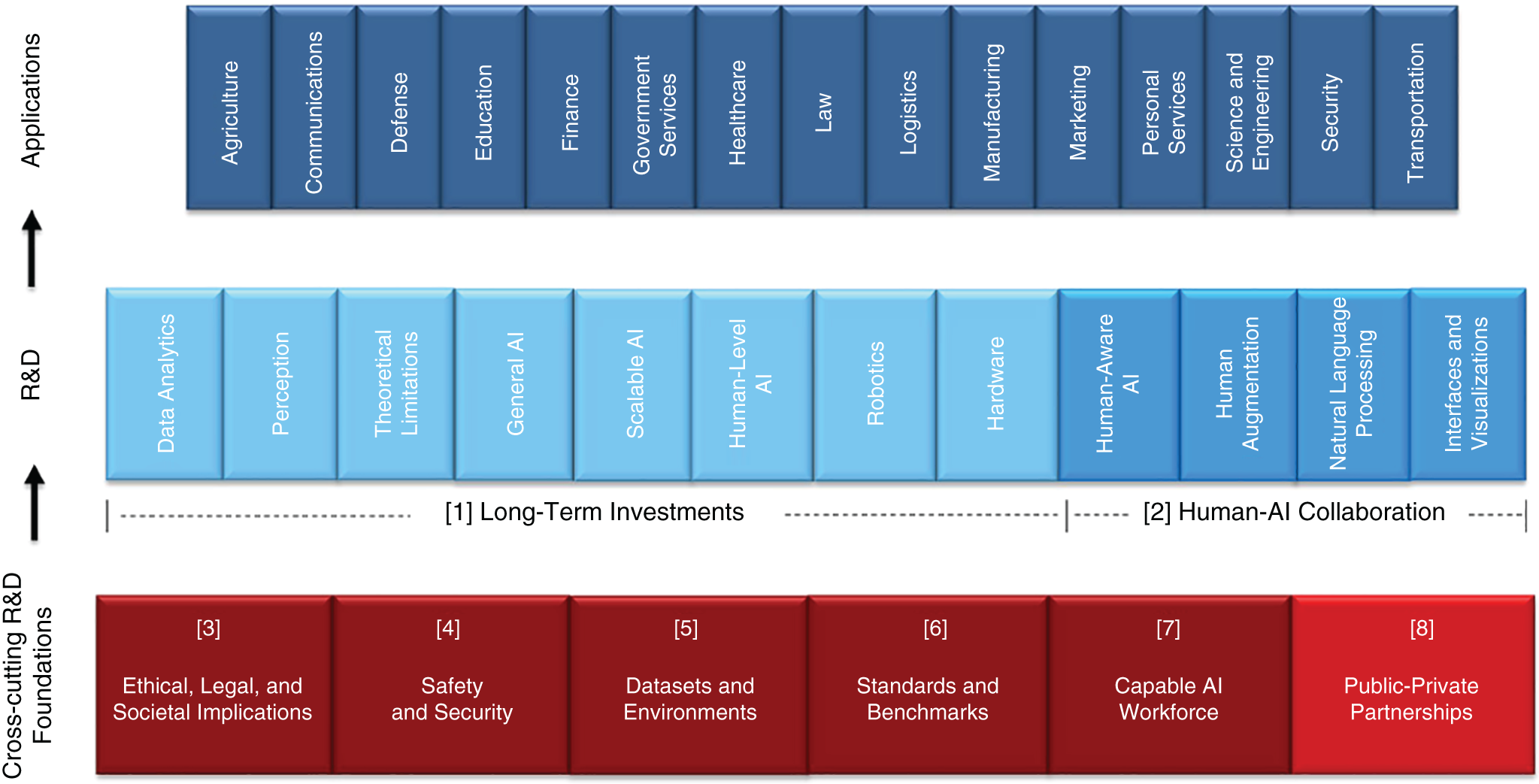

The story in the “Progress Report 2016–2019” depicted the National AI R&D strategy, which was composed of a total of eight strategies—seven from the 2016 plan and one from 2019 (Figure 6.2). Without any quantitative measures, the report pointed out the deployment of the strategies in various agencies. To the extent that the long-term investments were reported in the federal AI R&D budget by agencies, it does not clarify how it was deployed and what type of technology. Were chatbots considered R&D? Was RPA considered R&D?

The scorecard was really a measure of activities and not results. And it also created some concerns. For example, the R&D strategy to make long-term investment received a checkmark against it by agencies such as FBI, FDA, and GSA; however, the strategy 3 of Understand and address the ethical, legal, and societal implications of AI did not. In other words, the report said that FBI, GSA, and FDA had made long-term investments in AI without understanding and addressing the ethical, legal, and societal implications. That was a really scary insight—especially if we buy into the OSTP's ongoing obsession with what can be described as the killer robots' phobia. Of course, as one can expect, this was all some red tape bureaucratic check-the-box formality that was being tracked. It had no relationship to actual results. If it did, Chaillan would not have resigned and passed on the AI trophy to China (see Chapter 1).

The great denial by the OSTP continued. From the OSTP perspective, it got what it aimed for. A new AI initiative was established, more money was released for AI, and the large universities were promised big grants. Big Tech was happy, and that is all that mattered. The czars of AI now had an international limelight and a national strategy dominion.

| AI R&D Strategies | AFOSR | Army | Census | DARPA | DHS | DoD* | DOE | DOT | FBI | FDA | GSA | HHS | IARPA | NASA | NIFA | NIH | NIJ | NIST | NOAA | NSF | NTIA | ONR | VA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Make long-term investments in Al research | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 2. Develop effective methods for human-Al collaboration | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 3. Understand and address the ethical, legal, and societal implications of Al | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 4. Ensure safety and security of Al systems | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| 5. Develop shared public datasets and environments for Al training and testing | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 6. Measure and evaluate Al technologies through benchmarks and standards | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| 7. Better understand the national Al R&D workforce needs | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Expand public-private partnerships in Al to accelerate advances in Al | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

FIGURE 6.1 AI History in Government

FIGURE 6.2 AI Scorecard

THE THINKING WAS UPSIDE DOWN

A senior executive of Department of Defense's National Defense University commented, “Before I started teaching and when I was working in the government there used to be literally dozens of lobbyists for Enron and only one for Microsoft. Now it is swarming with tech lobbyists.” One remarkable difference between the launch of the Internet and of AI is that at that time there was no parallel to what we now call the tech giants. These multitrillion-dollar market valuation firms exercise tremendous power over policy, and it is showing up in the national AI strategy. The problem with having influence from large tech players is that they apply resources and power to sway policy in their power. For America to pay the bill for R&D that will eventually end up with Big Tech (via hiring professors or coinvesting) was an easy policy. Why would they disagree with that. As long as the policy was being crafted by supply side dynamics only and other important stakeholders and constituents in the economy were missing, it favored such narrow policymaking.

The supply side thinking—build it, and they will come—is evident in the national strategy diagram released by the OSTP. In their thinking, AI needed to be founded on some broad foundations such as safety and security, data sets and environments, standards and benchmarks, AI workforce, and public-private partnerships (Figure 6.3). Then government money should be pumped to fuel research in long-term investments in building the core capabilities such as robotics and data analytics, along with investment in human-AI collaboration consisting of NLP (natural language processing) and visualization. Once these two layers of R&D focus areas for investment and the foundational capabilities are combined and funded, the applications would somehow flood the industry on the applied side.

This was a dramatic mistake. A mistake that could cost America its leadership, its economy, its military and civilian superiority, and its future. The major mistake was to ignore that products and services create and embed certain information about them as they pass through their life cycle. This information has components of how people assign meaning to it, social construction of meaning, and several other factors. The information travels back and forth—where the eventual use and application of the technology is used to guide the early development, and the development process constantly evaluates the current and future realities through the process. Technology and science-led teams—such as OSTP—tend to ignore how that information embeds in products and services. The designers of such strategies do not consider the nature of competition or the strategic goals of AI-based competition. In a competitive environment where data and algorithms were defining success, speed was critical. The strategy must take into account several factors. For example, AI begets and attracts more data (for instance, an autonomous car collects more data every time it is out on the street), and learning is facilitated by additional data. There is a cost associated with acquiring and using data, and that implies that efficiency improvements in the underlying data processes would be key to making progress. Data is ubiquitous, and the same data can be used by different applications to learn different things in different ways, and having relevant data is critical. Unfortunately, the way the national AI plan was developed did not consider these issues. It was as if they took an inventory of different subfields in AI and, based on overly simplistic research assumptions, devised plans to pump money into them. That appears to be the extent of their strategic thinking.

FIGURE 6.3 Upside Down Planning

This may result in creating new research insights, innovation, inventions, and, yes, we will see new models—but they have no way to reach to the world of the applied front. To assume that industry will somehow reach and deploy new AI technologies is based on an assumption that the R&D projects launched in universities and institutions will be picked up by non-tech small, medium, and large companies and is imprudent. It is likely that only Big Tech will commercialize or deploy these innovations to expand the functions and features of its own product suite. This will create even more monopolization and even further consolidation.

Let us look at some relevant variables:

- The process of commercialization of technology in America is complex. Applications in the industry require creating a vision for the intelligent alternative of the current business models, industry structures, and the emergent structures.

- The managerial resistance in companies and agencies without fully understanding and embracing technology will be hard to overcome. When you don't know a new technology, you will find it risky to adopt it.

- The industrial structure of America has now been consolidated into a few firms in each sector. Smaller firms do arise—but mostly to become fodder for the large firms.

- The dynamics of the AI competition are such that they have a snowballing effect. The firm that deployed a solution earlier will get more learning data faster, and its algorithms will learn more.

- The existing IT infrastructures in firms will create tremendous inertia. Most companies and agencies are already struggling with the legacy IT and infrastructure problems.

- The capital dynamics—the bedrock of our economy—have changed. Capital itself can contribute to opacity and can cloud transparency. This will necessarily affect the adoption part of the technology.

- The cost of capital of riskier players will be higher, and hence investors will flock toward firms with lesser long-term risk—and therefore, among companies trying to solve the same problem, the one with lesser financial and operational risk will have better access to funding. This will give an unfair advantage to Big Tech.

When you consider all of those factors, you recognize that what OSTP calls national strategy is essentially the R&D plan for America—and even that is detached from the economic realities of the country. This would be analogous to a company stating its R&D plan is its overall business strategy. While this could apply to an early-stage firm, it is well understood that R&D is only one part of the business strategy. All the other parts are missing from the OSTP-led so-called national strategy.

The presence of scientific development and pumping all this money will undoubtedly create a production frontier with many different options of deployment of technology. The problem happens in the selection process on what parts of the frontier will have the best possible economic value and productivity gain. Not knowing that answer simply means that while scientific and even technological collection of production possibilities will be expanded, it will not necessarily be applied to create national value. While the neoclassical model assumes that decision-making takes place in information-rich environments and the market forces somehow work to iron out the inefficient possibilities and help winners to emerge quickly, we now know that these assumptions are not entirely true. Especially if we consider the state of the economic structure today—dominated by few very large firms, with high concentration of wealth and power, and an investment model that literally dumps hundreds of millions of dollars in early-stage firms—we can recognize that fallacy of our assumptions. They are not connected to reality.

GROUPTHINK ON STEROIDS

OSTP justifies the validity of its strategy by arguing that other countries have been inspired by the American national AI strategy. We find it hard to believe.

It is possible that some foreign countries are adopting and copying OSTP's strategy. But most likely that will be because those foreign countries may not know any better, and they will follow the American plan blindly. But for how long? Sooner or later the shallow strategy will shatter and expose OSTP's blunder.

Also, at this juncture it is worth it to analyze how China approached its AI strategy.

The Chinese plan is completely opposite to how OSTP approached the national strategy. The Chinese plan was based on first architecting the model of various industries and sectors from an intelligent and futuristic value chain perspective. Each sector was analyzed to determine all aspects of the value chain and what an intelligent value chain would look like. This plan was then expanded to analyze the enterprise capabilities at all levels in the value chain. It was then analyzed for what could be described as the integration points across sectors. Once that was clarified, determination was made to assess network, information, data, and integration needs—as well as identification of data sets within and across sectors. This was then followed by a parallel effort to coordinate research and development efforts by linking existing and future AI capabilities with the applied needs for the sectors and the economy. The why and when of industrial value chain formed the basis of AI strategy—which was then developed with the concept of the value chain of AI composed of multidimensional factors such as data, people, models, applications, problem-solution configurations, and other aspects. Finally, AI was architected for self-perception, self-cognition, self-control, self-adoption and feedback, self-learning, self-decision, and self-autonomy. Furthermore, the strategy for equipment and applications was linked with the enterprise strategy. This upside-down model compared to the OSTP's pie-in-the-sky is what drove China to accelerate and achieve their AI goals.

In the early stages of Chinese AI development there was less focus on AI governance and ethics, but that is rapidly changing. China is also developing AI governance and ethics frameworks. To what extent they will be integrated and adopted in AI applications and in society remains to be seen. In the US, however, as previously argued in the book, ethics and governance are being talked about a lot, but their actual implementation in Big Tech is still rudimentary. If Big Tech firms were serious about ethics and governance, then they would not need to spend tens of millions of dollars in lobbying efforts. Thus, the whole ethical and governance story seems to be less about the best interest of humankind and more about ostentation and pretension. The inordinate amount of time and energy spent on virtue signaling, ethics, and governance creates an unnecessary distraction. While all of those factors are critically important and should be pursued, it should be done sincerely and not just to create a distraction from AI adoption.

As we have argued elsewhere, it is possible that the focus on values gives the US an advantage as it increases the transaction cost of Chinese technology, but with China starting its own governance and ethics development for AI, the advantage may not last.

The detachment of R&D strategy and economics is at the core of the current national strategy.

It was the failure of this strategy that required America to incorporate plan B, which was to confront Chinese technological growth. Had this plan succeeded, America would have had no reason to institute plan B. Plan B comes with risk.

THE CADRE OF ETHICISTS AND FUTURISTS

As soon as AI was in the center stage, an army of ethicists and futurists got a seat at the table. The ethicists' job was to discover and debate the ethical sides of AI and develop AI governance. The futurists were to paint what the picture of the future would look like and talk about the future of work.

Both of these groups acquired significant power in the popular culture and social platforms. With decades of sci-fi depicting AI as acquiring the power to destroy the entire human civilization, starting wars, destroying Earth, using humans to produce energy, and ruling humans, it was easy for the ethicists to find a receptive audience.

While the Hollywood depiction of AI risks was being promoted on one end, more relevant and serious issues of AI were being ignored. For instance, it was revealed that AI being used in the DoJ and health care was biased and prejudiced against African Americans. As soon as such cases were identified, the need for AI governance became evident. But instead of the government taking steps to establish an AI governance and compliance process where it mattered, especially one that deals with social injustice, the entire narrative was turned into a fearmongering quest to play with the American psychology. Google dismantled and recreated several ethics boards. Facebook was called to testify many times. Allegations were made about Amazon following uncompetitive practices. But nothing changed. The real and practical governance and ethics were missing.

Somewhere in Europe, a group (OECD) met and established some general guidelines for AI governance and ethics. Those general guidelines were picked up by various groups, and instead of conducting a proper investigation and looking into American priorities and social issues related to AI, the White House blindly accepted those guidelines via subscribing to them.

The guidelines do not establish a system of governance for AI itself. In other words, there was no mechanism of implementing the recommendations. No process was set up for audit, validation, punishment, and so forth. No legislative parallel was established. No corresponding policy was formulated. AI governance became a nice to have marketing slogan and a bumper sticker—but not much beyond that.

STRATEGY 8

In the DC circles the government, academia, and Big Tech collaboration is often presented as the triangular relationship necessary to drive results. For instance, in the 2020 document OSTP writes, “Concurrent advances across government, universities, and industry mutually reinforce an innovative, vibrant American AI sector” (OSTP 2020 p. iv)—but unfortunately it is likely that the term “universities” means a few universities (usually MIT, Stanford, and CMU), industry implies those who can afford to throw big parties and conferences and give significant marketing exposure to government officials (Big Tech), and academia means professors whose research projects are bankrolled by Big Tech. While academia, industry, and government collaboration is absolutely necessary, unless done strategically and with a visionary leadership, it is anything but productive. A serious effort to do this is not driven by giving access to people who are the alma maters, friends, former colleagues, or club members of the czars of AI. That is what was completely different in the Clinton/Gore launch of the Internet. It was truly a revolution owned by the people and not just the few. Technological transformation was the bedrock of the Clinton/Gore presidency and Vice President Gore embraced, led, and evangelized the vision. There were large companies then also (although the power concentration was much lower), for example, Microsoft and IBM—but breathing space was created to launch companies such as Facebook, Google, eBay, and others. Now, we don't see that breathing space.

Today's politics, talent, and priorities are much different. A government official must never lose his or her sense of independence. It is hard not to be influenced by those sponsor conferences and events that place you in the limelight. It is not easy to let go of the relationships from the universities or companies one had worked in. It is not easy to ignore the influence from those who fund the events and conferences that make you famous and give you the platform. But that is exactly what the government officials must avoid.

Surrounded by lobbyists and Big Tech partners, government officials get the royal treatment. Accountability, responsibility, and transparency become hard when the entire job becomes pushing some vague and unmeasurable agendas. The hype itself becomes the performance measure. These carefree jobs are independent of the responsibility that comes with true policymaking that happens with the recognition that your country's competitive potential is at stake.

The gravity of the situation apparently did not dawn on the czars of AI. In their happy-go-lucky style, they continued to celebrate victories as the American competitiveness melted away around them. In report after report, the White House claimed triumph. But the hollowness of those claims became evident when a long study that spread over two years highlighted that America is falling behind.

Interestingly, now there were two claims—both coming from the government: the OSTP office claim that America was at the forefront of AI and in a remarkably strong position and an alternative claim from a commission known as National Security Council of Artificial Intelligence that American competitiveness was in trouble. The day of reckoning was fast approaching.

REFERENCES

- OSTP. 2020. “American Artificial Intelligence Initiative: Year One Annual Report.” February 2020. Available at: https://www.nitrd.gov/nitrdgroups/images/c/c1/American-AI-Initiative-One-Year-Annual-Report.pdf.

- Trump, Donald. 2019. “2016 AI R&D Update.” [Online]. Available at: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/National-AI-Research-and-Development-Strategic-Plan-2019-Update-June-2019.pdf.