6

Strategy: The Core of Every Balanced Scorecard

Roadmap for Chapter 6 In writing this book, my hope is that readers will find it relevant for years to come—just how many years is anyone’s guess. Of course, I can only dream about having the staying power of Sun Tzu, the Chinese General who authored a collection of essays on military strategy. The essays, best known to Western audiences by the title The Art of War, have been adapted to suit the needs of businesspeople, athletes, and politicians alike. The book, written over 2,300 years ago, has been a bestseller for years, and Sun Tzu is perhaps the most quoted Chinese personality in history outside of Confucius. Such is the power of strategy. Whether you wrote something valuable yesterday or 2,000 years ago, you’re sure to find a ready audience.

As the title of this chapter implies, strategy is truly at the core of every Balanced Scorecard. Essentially, the Scorecard is a tool for translating a strategy into action through the development of performance objectives and measures. My purpose in this chapter is to crack the quizzical code of strategy, demystify the concept, and providing you with tools to review your current strategy or enable you to craft a new and exciting future through the development of a freshly minted strategy.

To do that, we’ll explore the brief yet prodigious history of the subject, and examine what strategy is and, equally important, what it is not. Then, in case you’re still not convinced of the value of a strategy, we’ll examine some of the benefits a strategy can confer. We’ll then consider some of the many schools of strategic thought, and I’ll share with you one straightforward method of strategy development. The chapter concludes with a discussion of why the subject of strategy is so central to the Balanced Scorecard.

STRATEGY IS EVERYWHERE

As I was writing my first book, Balanced Scorecard Step-by-Step: Maximizing Performance and Maintaining Results, my wife and I were in the middle of a move to a new house. So, while conducting research and transcribing notes, I was simultaneously attempting to catalog the business archives of a lifetime in order to facilitate easy packing and unpacking—no easy chore for a selfdescribed packrat! I observed, by means of a not-so-scientific calculation, that approximately 90% of the documents in my possession made at least some passing reference to the subject of strategy. Now comfortably situated in our new home, my accumulation of business materials continues unabated. According to my “strategy meter,” I can tell you that the topic continues tov be at least casually addressed in virtually nine out of ten documents that come my way.

Strategy truly is everywhere. Interestingly, though, the formal field we label “strategic planning” has a relatively short history. The topic as we know it began to emerge in the 1950s and gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s. As we moved into the 1980s, global competition became an increasing threat, especially to the very vulnerable United States.1 To regain the advantage they once enjoyed, American businesses moved away from formal planning per se and focused instead on making processes more efficient, eliminating “nonvalue added” activities, and simply recognizing the new competitive landscape. Many operational improvements ensued but leaders recognized that simply developing more efficient operations did not represent the path to long-term success. They began to realize the road not taken—one that would lead to sustainable competitive advantage—was paved by a differentiating and defensible strategy.

WHAT IS STRATEGY?

Producing a universally acceptable definition of strategy is truly a Herculean task, so as a mental warm-up, let’s start with something a little less controversial: what strategy is not. Speaking on the current state of strategy development at many nonprofits, author and consultant Bill Ryan says, “some nonprofits develop a big pile of well-intentioned programs, ideas and directions that try to respond to every need and opportunity that comes along and might vaguely fit under their mission. There is always a reason to do something that no one else is willing to do if it relates to your mission. The harder thing as is often pointed out in strategy discussions is to have enough of a strategy to know when to say no, when to drop things, and when to pass up opportunities. Understand that yes, a need might be real, but you might not be the best response to it.”2 Before you move on, think about that quote, reread it if you have to, and critically examine your own organization’s approach to strategy development. Is Ryan talking about you? He’s putting a deep stake in the ground with this quote, specifically noting that strategy is not about being all things to all people. Deciding when to say no, and determining what you should not do is a critical component of strategy.

Public sector firms are not exempt from the temptation to serve everyone. Scorecard codeveloper Robert Kaplan suggests, “strategy can be a foreign concept to a public sector organization. These agencies have little incentive to take a longer-term view of their role. They may attempt to do everything for everyone, and can end up doing not much at all.”3 Virtually all public sector agencies could fall into this trap, but for the sake of illustration, consider the case of public education in the United States, an industry that has seen spending double in the past 30 years to over $450 billion in 2005. Researchers examining the performance of public school districts had this to say about strategy in the education arena: “The term ‘strategy’ is widely used in public education . . . but it generally doesn’t mean much . . . About a third of districts studied trotted out thick binders that they called their strategic plans, which were loaded with pages of activities that lacked rhyme or reason.”4

If strategy is not about being the same as everyone else, what is it about? Commonly quoted strategy expert Henry Mintzberg provides this excellent synopsis of the subject: “My research and that of many others demonstrates that strategy making is an immensely complex process, which involves the most sophisticated, subtle, and, at times, subconscious elements of human thinking.”5 Maybe so, but that doesn’t help us much in nailing down a definition! The difficulty with defining strategy is that it holds different meanings to almost all people and organizations. Some feel strategy is represented by the high-level plans management devises to lead the organization into the future. Others would argue strategy rests on the specific and detailed actions you’ll take to achieve your desired state. To others still, strategy is tantamount to best practices. Before I offer a definition of strategy, let’s look at some of the key principles of this subject:

• Different activities. As explained in the preceding paragraph, strategy is about choosing a different set of activities, the pursuit of which leads to a unique and valuable position in the environment.6 If everyone were to pursue the same activities, then differentiation would be based purely on operational effectiveness and cost. Some organizations venture well beyond different in their pursuit of carving out a defensible strategic position. Take Canon, for instance. Their CEO, Hajime Mitarai says: “We should do something when people say it is ‘crazy.’ If people say something is ‘good,’ it means that someone else is already doing it.”7 Reaching beyond the ordinary and casting your net into the unknown and unproven can often generate the breakthroughs that strategy promises.

• Trade-offs. Effective strategies demand trade-offs in competition. Strategy is more about the choice of what not to do than what to do. Organizations cannot compete effectively by attempting to serve everyone’s needs. The entire organization must be aligned around what you choose to do and create value from that strategic position.8

• Fit. The activities chosen must fit one another for sustainable success. Many years ago Peter Drucker articulated the “Theory of the Business.” He suggested that assumptions about the business must fit one another to produce a valid theory. Activities are the same; they must produce an integrated whole.9

• Continuity. Generally, strategies should not be constantly reinvented, with emphasis on the word constantly. While we would expect a strategy to evolve in the face of dramatic changes in your operating environment, a continuous preoccupation with updating strategy is certain to lead to confusion and skepticism. The strategy crystallizes your thinking on basic issues such as how you will offer customer value and to which customers. This direction has to be clear to both internal (employees) and external (customers, funders, other stakeholders) constituents.10 Changes may bring about new opportunities that can be assimilated into the current strategy—new technologies for example.

• Various thought processes. Strategy involves conceptual as well as analytical exercises.11 As the Mintzberg quote earlier in this section reminds us, strategy involves not only the detailed analysis of complex data, but also broad conceptual knowledge of the organization, environment, and so on.

Using the preceding discussion as a backdrop, I offer my, admittedly succinct, definition of strategy: Strategy represents the broad priorities adopted by an organization in recognition of its operating environment and in pursuit of its mission. Though short on words, this definition is long on implications.

“Broad priorities” means just that: the overall directional areas the organization will pursue to achieve its mission. For many, there is a tremendous appeal of turning their strategy document into an endless wish list of programs or initiatives. Robert Kaplan has seen this in action: “Most nonprofits don’t have a clear succinct strategy. Their ‘strategy’ documents often run upwards of 50 pages, and the so-called strategy consists of lists of programs and initiatives, not the outcomes the organization is attempting to achieve.”12 Outlining every conceivable action that somehow marginally fits with your mission is undoubtedly seductive to public sector and nonprofit organizations alike. After all, such an approach allows you to cover all the bases, please all possible stakeholders, and consider every potential circumstance. What it does not do, however, is allow even a hairline crack of opportunity to execute the outcomes most representative of what constituents desire.

I worked with a nonprofit recently that had just completed a strategic planning exercise and wanted to take the opportunity to implement a Balanced Scorecard to assist with the execution of the plan. One glance at the War and Peace-sized document and I knew their hopes were about to be grounded. Absent from the tome were any true priorities. Instead, the “strategy” contained specific tactics by the hundreds, all dutifully accompanied by dates, responsible parties, and pages of sub-tasks. What’s so bad about that, you ask? This organization was staffed by less than 30 people. By my estimation, they would have to work literally day and night for several years to approach completion of even a fraction of the plan.

Consider a small, local AIDS organization. Its strategy could detail every initiative it plans to undertake for the upcoming year. A better approach would be to inform its stakeholders and employees as to what overall approach it will take in serving the community. Perhaps it would choose to focus on education, or prevention, or building community support. These are strategies. They set direction and provide a context for the development of objectives and measures, which will follow with the Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard.

In addition to the content of strategic plans, nonprofit and public sector agencies would be well-served in casting a critical eye on the order of items that make up the document. Frequently, these organizations will outline their mission, then a number of specific initiatives, and finally key goals and objectives. In my opinion, this is backwards. Mission always begins the process, on that we agree. However, next comes values and vision, then strategy which represents the broad, overall priorities of the organization. Translating that strategy is accomplished through the development of objectives on a Strategy Map, followed by measures and targets on a Balanced Scorecard. Finally, specific initiatives are put in place to help the organization achieve its Balanced Scorecard targets.

DO WE NEED A STRATEGY?

I recently had a very telling conversation with a consultant to nonprofit organizations. He continually encounters boards of directors who haven’t accepted that their organizations need to develop a strategy. This is quite ironic to him since in the nonprofit model, it is the board that is charged with setting the direction of the organization. The irony is extended when you consider the fact that most leaders are expressing a desire to spend more time on strategic issues and less on operational demands.

The uplifting words contained in a mission, values, and vision represents nothing but wishful thinking unless accompanied by a strategy. The strategy gives life to the lofty aims declared in these documents. While mission, values, and vision dwell in the realm of “why” and “who,” the strategy burrows into the trenches of “how.” A well-conceived and skillfully executed strategy provides the specific priorities on which you’ll allocate resources and direct your energies.

Here are but a few of the many benefits that arise when you develop and commit to executing a strategy:13

• Strategic thought and action are promoted. Rather than focusing on the rote details of the moment, a strategy directs the energies of all employees towards what is truly important within your organization.

• Decision making can be improved. The important decisions in your organization can be considered through the prism of strategy, not the glare of urgent activities.

• Performance is enhanced. A strategic focus ensures your entire organization is focused on achieving overall goals. Add to this potent mix aligned processes for decision making, resource allocation, and performance management, and performance is almost certain to improve.

Of course, strategy is central to the Balanced Scorecard. To grab hold of the maximum benefit the Scorecard has to offer, you should use it as a mechanism for translating your strategy into action. The final section of this chapter will detail the vital link between strategy and the Balanced Scorecard.

MANY APPROACHES TO STRATEGY FORMULATION EXIST

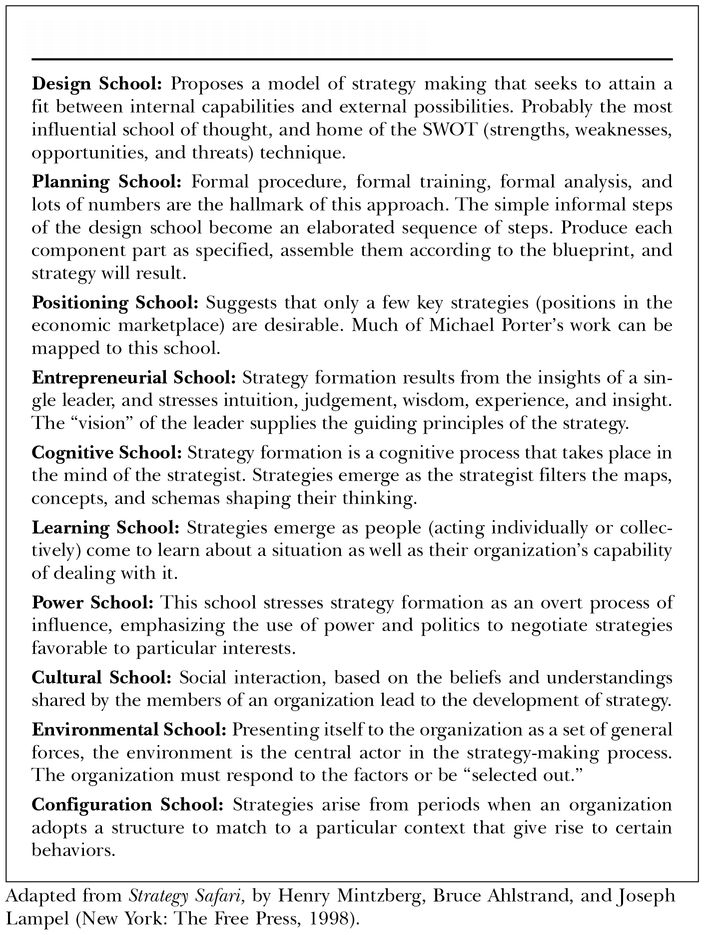

Part of the confusion surrounding strategy stems from the fact that the field is as crowded with approaches and methodologies as a beach with people and umbrellas on the 4th of July. Military applications notwithstanding, never has a field with such a relatively short history spawned such a multitude of techniques. Just a partial listing of strategic modes would include: strengths and weakness analysis, portfolio approaches, shareholder value, economic value added, real options, core competencies, strategic intents, profit zones, and disruptive technologies. New entrants are constantly joining the fray. One of the latest techniques is known as “Blue Ocean Strategy.” Developed by Professors Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, this approach seeks to “push for a quantum leap in buyer value while simultaneously lowering the industry’s cost structure.”14 Is your head spinning yet? Well, to really get it going, I’ll reintroduce a book I first mentioned in Chapter 1, Strategy Safari. It extensively documents a whopping ten different schools of strategic thought, for those intrepid enough to make such a journey. The ten schools are presented in Exhibit 6.1.

Unfortunately, no single “right” method exists. What works for one organization at a distinct point in time may not work for another organization at a different juncture. Conversely, I could also say “fortunately” there is no single right approach because the importance of strategy has stimulated never-ending research, and despite some confusion and head-scratching around the lexicon produced by the field of strategy, we’re all better for the efforts. In the next section, I present the most common elements of a strategic planning effort.

Exhibit 6.1 Ten Schools of Strategic Thought

STRAIGHTFORWARD APPROACH TO STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

Entire books, seminars, and MBA courses have been dedicated to this topic, and though formal and detailed strategic planning techniques are beyond the scope of this book, strategy and the Balanced Scorecard are so inextricably linked that it would be a disservice not to share at least the basics of strategic planning for those of you with limited experience in this area. Therefore, consider this a primer on the subject. It will serve you well in assessing your current process against common practice, as it provides the essentials of developing a unique strategy for your organization.

The strategic planning method that is outlined here represents a composite of many different techniques advocated by a wide range of practitioners, consultants, and academics. The six steps are: getting started; performing an environmental scan; conducting a stakeholder analysis; analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT); identifying strategic issues; and developing strategies. When developing a strategy, most pundits suggest you first develop your mission, values, and vision that set the foundation for your strategy work. We covered those building blocks in Chapter 5, so for the purposes of this discussion, I’m making the assumption they are present when you begin your strategy efforts.

Step 1: Getting Started

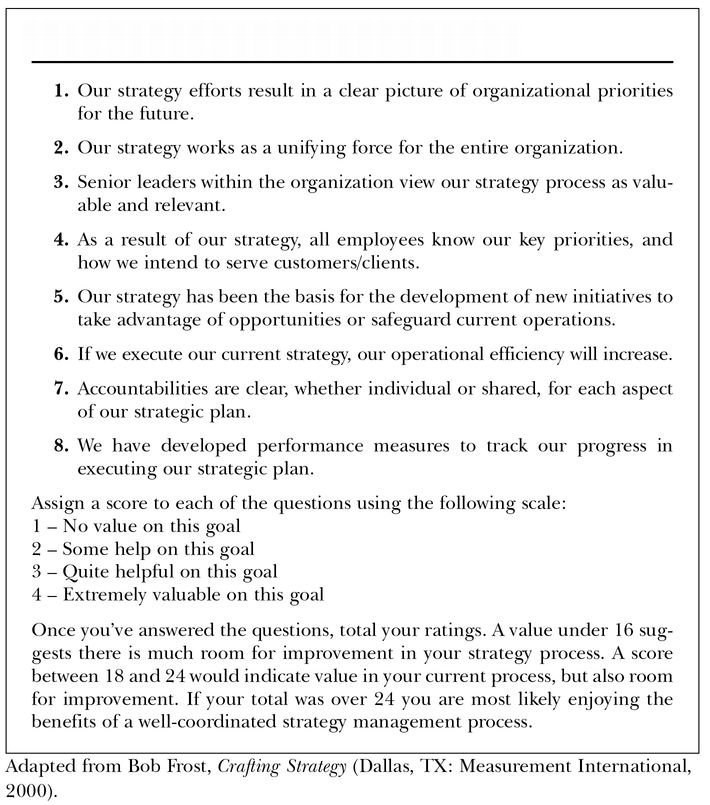

As with your overall Balanced Scorecard implementation, you must ensure your organization is ready to embark on a strategic planning process. As a first step, you should review the effectiveness of your current planning efforts. Exhibit 6.2 provides a number of questions to consider regarding your current processes. Items with lower scores are ideal candidates for improvements that can be addressed in the current strategy development endeavor.

Strategic planning requires the commitment of time and attention from your top leaders as well as a willingness to provide ample resources for the effort. If your leaders are mired in current crises or anticipating a key legislative change, then perhaps this isn’t the best time to embark on the task of developing a new strategy. To make the decision, you’ll have to weigh the importance of the undertaking against the probability of success resulting from limited leadership involvement.

Once you’re ready to plan, it’s time to consider your objectives for drafting a new strategy. Any gap you’ve uncovered as a result of answering the questions in Exhibit 6.2 may provide an impetus for developing a new plan. You could be facing any number of issues that necessitate the development of a new strategy. However, it’s important to distinguish between issues of truly strategic significance and those of operational dilemmas. Any crisis situations or issues with a time window of less than a year fall into the latter category. Fundamental issues of a longer-term nature that relate to your core service are more likely to be strategic.

Exhibit 6.2 Evaluating Your Current Strategy Process

Do you know your formal and informal mandates? The formal mandates of your organization spell out in detail what it is you are specifically required to do and not to do. Laws, ordinances, articles of incorporation, and charters are likely sources of information on this topic. No less important are the informal mandates or expectations key stakeholders require from you. Since we defined strategy as the broad priorities adopted by an organization in recognition of its operating environment and in pursuit of its mission, be sure any strategy you develop is consistent with the mandates you’re required to observe.

The final step in getting started requires you to take a step back. To develop context for your effort, it’s often illuminating to view your organization from an historical perspective. Chronicle the history of your public or nonprofit agency from its earliest developments to the present day realities you face. Along the way, you can document programs and services you’ve offered and the challenges and successes of days past. We all know experience is the best teacher and you can use the history of your own organization to learn from both past missteps and successes alike.

Those engaging in an exercise such as this frequently have a tendency to magnify past transgressions and to focus primarily on faults of the organization. If you find this is the case at your agency, consider using the Appreciative Inquiry approach to balance the deck. Developed in the early 1990s by David Cooperrider at Case Western University, Cleveland, Ohio, this approach focuses on an organization’s achievements rather than its problems.15 Participants are encouraged to share personal accounts of the organization operating at “peak performance.” The stories describe the organization at its most alive and effective state. Based on this inspirational task of organizational archeology, workshop attendees then seek to understand the conditions that made peak performance possible—values, relationships, enabling technologies, and so on. From this input, a strategy is developed that draws on the very best the organization has to offer its customers, clients, employees, and all other stakeholders. As an old song says, you have to Accentuate the Positive.

Step 2: Performing an Environmental Scan

The Center for Association Leadership recently conducted a groundbreaking study with a very lofty aim: determining what attributes make a “great” association. In the spirit of similar efforts in the private sector, including the work chronicled in the book Good to Great, the research team used a matched-pairs approach, studying nine associations that had achieved consistent success over a multiple-year period and compared them on several criteria with associations that had similar missions or had served similar memberships, but had not experienced enduring success. The study revealed many insights, including the fact that successful organizations consistently scanned their environments in a relentless effort to acquire information they could use to better serve their membership.16

This step involves the painstaking acquisition of data from a variety of sources within your organizational orbit, and analyzing that material to assist you in coming up with a unique strategy. Outlined are a number of potential sources for your investigation:

• Societal Trends. How are the needs and experiences of your customers changing?

• Demographics. In most Western countries, the population is aging rapidly. What impact does this have on the products or services you deliver? And how will an aging workforce impact your ability to meet service demands in the future?

• The Economy. Economic tides can wreak havoc with public sector and nonprofit agencies dependent in large measure on third parties for funding. The vicissitudes of market conditions must be considered as you plot your fiscal plan and paint your broader strategic canvas.

• Technology. In a macro context, how is popular technology, for instance the Internet, shaping the way you conduct your business?

• The Political Situation. How would a new government and their positions affect the way you work towards your mission?

• Changing regulations. Is there impending legislation that may cause you to reconsider how you serve your constituent base?

• Competition. Who else does what you do? What are their competencies, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats? Should they grow in scope, size, or both, how will you react?

Mining these sources will inevitably lead to many stimulating discussions, spirited debates, and, hopefully, moments of clarity as you transform the raw data into strategic insights. As you grapple with these questions, be mindful of your current product and services and critically examine them in light of the conclusions you’re drawing. Based on what you’ve discovered, are there offerings you should abandon—things that simply don’t fit with the environment as it is presenting itself to you today? As much as we’d like to, we simply can’t configure the world to always be consistent with our wants and preferences. We need to be ruthlessly realistic and face the facts. Dare to be bold when conducting these thought experiments, throw away the sacred cows, and listen to what the data is telling you. A rather dramatic example of such thinking is the story of Spanish explorer Hernando Cortez who landed with his soldiers at Veracruz, Mexico in 1519. As the troop headed inland, conditions deteriorated rapidly: disease, deplorable living conditions, and a resolute enemy. Orienting himself to this, and realizing his demoralized soldiers could give up the fight at any moment, Cortez took an extraordinary step—he burned the ships. No turning back now, only the grim face of reality staring menacingly and the necessity to adapt or perish. 17 Have you burned your ships? What dramatic action can you take to forever alter the course of your organization’s fate?

Step 3: Conducting a Stakeholder Analysis

You could develop the most insightful strategy ever conceived, but unless it is responsive to the needs of your stakeholders, it isn’t worth the three-ring binder it’s bound to end up in. All organizations, whether private, public, or nonprofit exist primarily to serve and satisfy the needs of key stakeholders. Only by meeting their needs, and in some way improving their lives, will an organization be able to work towards the fulfillment of its mission.

Exhibit 6.3 Partial List of Public and Nonprofit Stakeholders

The first step in any stakeholder analysis is to identify specifically who your key stakeholders are. This can prove to be a complicated endeavor for any organization, but given the web of relationships that exist for most public and nonprofit agencies, it can be a substantial challenge. Exhibit 6.3 outlines some of the many stakeholder groups that may apply to your organization. When compiling your list of stakeholders, it’s best to cast the net as widely as possible. Don’t limit yourself to the obvious choices; instead, attempt to identify all those who are touched by your organization.

With stakeholder groups identified, you can move on to a determination of their requirements. Interviews and surveys are proven methods for gathering this intelligence. Of course, experiences gleaned from working directly with these groups should also provide you with some excellent insights you can capture. While canvassing these sources, look for shared requirements from disparate stakeholder groups. Universal customer requirements will significantly ease the task of forming strategies. When the converse appears, and you encounter stakeholders with vastly different requirements, the true challenge of strategy has been thrust upon you. Recall from our earlier discussions that strategy is not about being all things to all people—that results in chaotic efforts yielding dissatisfied customers and few results. In the face of various and sometimes conflicting demands, you must make the determination, based on your resources, the skill sets of your staff and volunteers, and any mandated requirements, truly aligned with your mission, which you are the best equipped to meet. Conducting that exercise will peel away layers of confusion and lead to the development of a galvanizing strategy.

One final caveat: Be sure to challenge your assumptions when considering stakeholder requirements, because what you think stakeholders require and what they actually desire could be two very different things. A light-hearted example comes from the U.S. Forest Service. You might think the average visitor to a national forest would be looking for easy-to-read maps and lots of recreational opportunities, right? That could be part of it, but what years of complaint data has yielded is the enlightening finding that visitors just want toilets that don’t smell! In response to this most critical of stakeholder needs, the U.S. Forest Service dubbed 1990 “The Year of the Sweet Smelling Toilet,” as it adopted the latest research and science to construct state of the art “facilities” that expunged the air of any malodorous offenses.18

Step 4: The SWOT Analysis

Strategies emerge out of a deep understanding of your organization’s place in its current and anticipated operating environment. An excellent tool to help complete this assessment is the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. This widely recognized methodology is simple to administer and facilitate and can yield swift and profound results. The SWOT analysis consists of finding answers to four fundamental questions:

• What are our organization’s strengths?

• What are our organization’s weaknesses?

• What opportunities are present for our organization, the pursuit of which will lead us toward our mission?

• What threats do we face that may endanger the pursuit of our mission?

When discussing strengths you should ask what it is you really do well or what advantages you have that others cannot easily duplicate. Weaknesses represent areas in which improvements are necessary if you are to work towards fulfilling your mission. Changes in your environment, be they demographic, legislative, or pertaining to public opinion may represent opportunities to the organization. Finally, threats represent the converse of opportunities and can be viewed as changes that may potentially hinder your ability to serve stakeholders.

Typically, strengths and weaknesses relate to issues residing within the organization. Among the subjects frequently encountered in a discussion of strengths and weaknesses are: employee competencies, organizational structure, customer and client service, agency reputation, governance, facilities and equipment, fiscal position, technology, communication, culture, and values. Opportunities and threats are normally considered to be external issues that affect the organization. Discussions on these topics will often yield comments relating to: changing client needs, demographic shifts, economic stability (or instability), competition, legislative changes, and technology.

While SWOT is well known and universally utilized, many organizations forget the suffix “analysis” that forms such a crucial part of this process. Perhaps the ritualistic listing of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats serves enough of a cathartic purpose that no energy is reserved for the important task of analyzing these findings. However, insights will often bloom out of a critical examination of the interplay among the elements. Two intersections are of particular interest: strengths and opportunities and weaknesses and threats. When crafting strategy, it makes great sense to exploit the matching of particular strengths with outstanding opportunities. That’s how breakthroughs in performance are born. Consider the example of one prenatal health clinic. Among the many strengths it cataloged during a SWOT exercise was “highly knowledgeable workforce.” It was also fortunate enough to list a number of opportunities, one of which was, “new prenatal care techniques that can greatly help our clients.” Until this point in its evolution, the clinic had focused almost entirely on service delivery. But when analyzing the results of the SWOT, the clinic’s leaders saw the potential for a new strategic direction to emerge: Why not combine the core strength of knowledgeable workers with the opportunity presented by new prenatal techniques and focus on providing education services? They recognized they were in the unique and enviable position of employing some of the brightest professionals in the field who could quickly assimilate the latest research and effectively articulate it to their clients. They hypothesized that by providing education services and increasing awareness of the latest techniques available, clients would be armed with the knowledge required to make better health choices. Ultimately, the clinic’s leaders believed this would lead to a reduction in prenatal care issues later in a pregnancy. A new strategy was born.

SWOT analyses are by necessity “point in time” exercises. Given the many insights you can garner from this process, consider making it part of your ongoing Performance Management process. While you wouldn’t want to engage in a SWOT every month, it’s not unreasonable to suggest, given the unprecedented pace of change in today’s world, a review at least annually, if not semiannually.

Step 5: Identifying Strategic Issues

Thus far in the process, you’ve considered our objectives for developing a strategy, reviewed your organization’s mission and mandates, scanned the environment, identified key stakeholders, and considered strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Some may consider these steps almost academic in nature, hence not “real,” since they do not reflect a bias toward action. All that will change in step five as you carefully analyze the material you’ve captured to date and frame the key strategic issues facing your organization.

Strategic issues can be defined as “fundamental policy questions or critical challenges that affect an organization’s mandates, mission, and values; product or service level and mix; clients, users, or payers; or cost, financing, organization, or management.”19 Thus a strategic issue could be anything from “a shortage of long-term office space requirements” to “potential funding shortfalls” to “changing demographics of key clients.” When documenting issues, it’s important to phrase them as a challenge facing the organization and outline the specific ramifications that await you should you choose to ignore the issue. Given the input you have at your disposal to help you generate issues—mission, environmental data, mandates, SWOT, stakeholder needs—it should not come as a surprise to learn that many organizations can quickly compile dozens. Distinguishing between the truly strategic issues and merely operational ones will assist you in keeping the list at a manageable level. Strategic items are those that:

• Appear on the agenda of your board or elected officials and leaders.

• Are longer term in nature.

• Affect the entire organization.

• Have significant financial ramifications.

• May require new programs or services to address.

• Are “hot buttons” for key stakeholders.

• May involve additional staff.

Identifying the key issues facing your organization may be accomplished in a number of ways. Brainstorming as a group is one option. Using this technique, a facilitator will instruct the strategic planning team to generate as many possible issues as they can within a limited timeframe. All issues are captured on flip charts or a computer, with the contents projected onto a screen in the room. Once all issues have been identified, the group begins the sometimes arduous task of clarifying and classifying the issues, ensuring there is a common understanding among the team of exactly what the issue is, why it is an issue in the first place, and what the consequences are of not directly addressing it.

Another possible method of capturing issues is a derivative of the Appreciative Inquiry approach presented earlier in the discussion of chronicling the organization’s history. Recall that this approach focuses on an organization’s achievements rather than its problems. This exercise may be applied to the discussion of issues. Participants are encouraged to envision the organization operating at peak performance and then consider any obstacles standing in the way of their achievement. The obstacles will represent strategic issues that must be mitigated in order for the organization to reach its desired state.

Step 6: Developing Strategies

With the issues facing the organization clearly enumerated, it’s now time to develop strategies that directly address the issues and allow you to work towards fulfilling your mission. One effective method of producing strategies centers on providing responses to five key questions relating to each of your strategic issues:20

1. What are the practical alternatives we could pursue to address this issue?

2. What potential barriers exist in the realization of the alternatives?

3. What action steps might we take to achieve the alternatives or overcome the barriers to their realization?

4. What major actions must be taken within the next year (or two) to implement the action steps?

5. What actions must be taken in the next six months, and who is responsible?

Have you ever heard the term green-field brainstorming? It suggests an activity in which people engage in the purest form of the art of brainstorming, assuming nothing and simply listing any and all aspects of a particular situation or issue. Generating strategies using this technique may yield many options, but as you know, it’s the implementation of strategy that produces real benefits. Therefore, your goal should be to elicit strategies that have a reasonable chance of successful execution. Using the five questions presented will stack that deck in your favor. The first question is straightforward and is reminiscent of the brainstorming technique just discussed. However, beginning with the second question, the level of pragmatism is quickly escalated. Discussing barriers at this point will lead to open and frank discussions about the real probability of successfully implementing the proposed strategy. Not that barriers should be considered insurmountable brick walls; in fact, question three promotes the use of creative thinking in overcoming the barriers to success. The final two questions prompt the team to consider specific steps necessary in implementing the strategy, and equally important, assigning ownership for results.

In the discussion of the SWOT technique, I emphasized the use of the word “analysis,” by suggesting you look at the interplay among the elements. So it is with strategy. While some strategies will stand on their own, you may find some will tend to form clusters that emerge into themes. Public and nonprofit organizations will often find their strategies contain overarching strategic themes that converge around broad service areas within the organization. For example, the Southeastern Pennsylvania chapter of the American Red Cross has identified four strategic “priorities.” These priorities emerged after conducting both an internal and external assessment of strategic challenges and opportunities. The four priorities are:

• Become a more customer-focused organization and heighten visibility in every way.

• Grow financial resources available for programs.

• Continuously improve systems to achieve operational excellence.

• Maximize people resources.

Exhibit 6.4 Sample Strategic Priorities for Each BSC Perspective

| Customer Perspective | Financial Perspective |

|---|---|

| Become a more customer-focused organization and heighten visibility in every way. | Grow financial resources available for programs. |

| Internal Process Perspective | Employee Learning and Growth Perspective |

| Continuously improve systems to achieve operational excellence. | Maximize people resources. |

Did you notice anything about the Red Cross’s strategic priorities? All are extremely noble and admirable themes, indeed. But what jumps out at me is how nicely they map to a Balanced Scorecard framework. And, in fact, that is exactly what this chapter of the Red Cross did: It made each of these priorities the cornerstones of the four Scorecard perspectives, as depicted in Exhibit 6.4.

While the situation presented in Exhibit 6.4 is convenient, don’t feel you have to “force-fit” your strategies to the Scorecard perspectives. That said, it certainly doesn’t hurt to keep in mind that success is a product of strategy execution, and the vehicle of that execution is the Balanced Scorecard. I’ll conclude the chapter with a look at precisely why strategy is so important to the development of the Balanced Scorecard.

STRATEGY AND THE BALANCED SCORECARD: A CRITICAL LINK

A couple of holiday seasons ago, I had the chance to read a newspaper article chronicling some of the many New Year’s resolutions one reporter discovered when speaking to patrons at a particular nightclub. (Appropriate choice of venues for such an assignment, don’t you think?) I can just hear the resolutions becoming more grandiose with each passing hour (and drink). The list was replete with the usual suspects: quit smoking, lose weight, get my financial house in order, and so on. But one gentleman’s account stood out from the crowd: he resolved to get in shape, had decided to buy books on fitness, join a health club, and cook more balanced meals. I was impressed by the specific accounting he made of what he was going to do and thought it lent an air of authenticity and legitimacy to his resolve. But then I realized that deciding is not doing. He could buy a thousand books on fitness and watch the Food Network from dusk til’ dawn and still not get in any better shape. Execution is the key. So it goes with organizations. While the formation of a strategy may initially impress your stakeholders, it’s the results borne of strategic execution that really get their attention. The Balanced Scorecard helps you turn the good ideas and potential of strategy into tangible results.

The Scorecard provides the framework for an organization to move from deciding to live their strategy to doing it. A well-constructed Strategy Map and Balanced Scorecard will describe the strategy, breaking it down into its component parts through the objectives and measures chosen in each of the four perspectives. Far from an academic exercise, this process will force you to specifically articulate what you mean by terms frequently residing in strategic plans, such as “excellent customer service,” “continuous improvement,” or “enhanced staff competencies.” Using the Scorecard as a lens through which to view these terms, you may determine that “excellent customer service” equates to “meeting client requests within 24 hours.” Now you have created a focus for the entire organization. While “excellent customer service” could be debated endlessly, depending on your personal point of view, “meeting requests within 24 hours” is objective, measurable, and can act as a focal point for channeling the energy of employees across the agency.

Can you develop a Balanced Scorecard without a strategy? Sure, and some organizations will do just that. But consider for a moment what such a Scorecard would consist of. You would still have a mix of financial and nonfinancial indicators straddling the four perspectives. What you would not possess, however, is a common linkage or theme running through the Scorecard. Your strategy is the common thread that weaves through the Scorecard tying the disparate elements of customers, processes, employees, and financial stakeholders into one coherent whole. Without the unifying theme represented by your strategy, you’re left with a collection of good ideas that lack a coherent story or direction. The Balanced Scorecard and strategy truly go hand in hand. Kaplan and Norton sum up this subject very well. “The formulation of strategy is an art. The description of strategy, however, should not be an art. If we can describe strategy in a more disciplined way, we increase the likelihood of successful implementation. With a Balanced Scorecard that tells the story of the strategy, we now have a reliable foundation.”21

Earlier in the chapter, while discussing environmental scans, I referenced a study conducted by the Center for Association Leadership on the attributes of extraordinary associations. The researchers note in their findings that “remarkable associations don’t just emphasize thinking strategically. They find it equally important to act strategically; they consistently implement their priorities . . . In other words, among remarkable associations, it matters what you do, not just what you say.”22 Words to live by.

NOTES

1 Bob Frost, Crafting Strategy (Dallas, TX: Measurement International, 2000), p. 7.

2 Interview with Bill Ryan, September 17, 2002.

3 Robert S. Kaplan, BSC Report, vol. 2, no. 6.

4 Stacy Childress, Richard Elmore, and Allen Grossman, “How to Manage Urban School Districts,” Harvard Business Review, November 2006, pp. 55-68.

5 Henry Mintzberg, “The Fall and Rise of Strategic Planning,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1994.

6 Michael E. Porter, “What is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, November-December 1996.

7 Tom Peters, Re-imagine (London: Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2003), p. 302.

8 Michael E. Porter, “What is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, November-December 1996.

9 Ibid.

10 Keith H. Hammonds, “Michael Porter’s Big Ideas,” Fast Company, March 2001.

11 E.E. Chaffee, “Three Models of Strategy,” Academy of Management Review, October 1985.

12 Robert S. Kaplan “The Balanced Scorecard and Nonprofit Organizations,” Balanced Scorecard Report, November-December 2002, pp. 1-4.

13 John M. Bryson, Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995), p. 7.

14 W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, Blue Ocean Strategy (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2005), p. 12.

15 Based on a paper delivered by Gervase R. Bushe at the 18th Annual World Congress of Organizational Development, Dublin, Ireland, July 1998.

16 Michael E. Gallery, Chair, Measures of Success Task Force, 7 Measures of Success (Washington DC: ASAE, 2006).

17 Tom Peters, Re-imagine (London, Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2003), p. 302.

18 John M. Bryson, Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995), p. 74.

19 Ibid., p. 30.

20 Ibid., p. 139.

21 Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001).

22 Michael E. Gallery, Chair, Measures of Success Task Force, 7 Measures of Success (Washington DC: ASAE, 2006), pp. 53-54.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.