Introduction

One of the defining features of Google's management model – alongside it's fun working environment – is its analytical, data-driven approach to decision-making. New products are launched through carefully controlled experiments. Highly paid persons' opinions – HIPPOs for short – are disdained. The company's chief economist has even predicted that the sexy job in the next 10 years will be statisticians.

So it is no surprise that when Google started to review its management practices, in early 2009, it took a data-driven approach. Led by the VP for people operations, Laszlo Bock, and codenamed Project Oxygen, the initiative involved gathering more than 10 000 observations from performance reviews, feedback surveys, and interviews1. After a lot of number-crunching, as well as some subjective interpretation, the project team came up with a list of eight ranked factors that defined the really good managers at Google:

This is a good list. We can all agree, I think, that these are desirable attributes for managers. It even includes a few surprises – technical skills had always been considered very important in Google's geeky, technocratic environment, yet they were ranked far lower than “softer” skills around coaching and empowering people. The analysis helped Google to think much more stringently about the types of people they wanted as department heads and team leaders.

But it is also a useless list. Why? Because we already knew all this. With the possible exception of “don't be a sissy,” I have seen versions of this list in every book ever written on management. When I run seminars with executives or with MBA students, it takes about 20 minutes to construct this list simply by drawing out the experiences of those in the room. Adam Bryant, writing in The New York Times, called the list “forehead-slappingly obvious … reading like a whiteboard gag from an episode of The Office.”

So here is the problem. Let's say you work at Google and you want to improve your managerial skills. Are you going to study this list and evaluate your progress against each of the eight points? Are you going to pin it up next to your desk, so you can refer to it next time you are meeting with one of your team? My guess is you are not. This list is about as useful to you in becoming a better manager as “ten steps to a healthier diet” to an overweight businessman or “how to perfect your golf swing” to an aspiring Rory McIlroy. In all these cases, we can read the words and we know what we are supposed to do. But we don't know where to start, we don't know how to prioritize among the list of points, and we don't know how to get out of our old habits. So our behavior remains unchanged.

This gap between what we “know” and what we “do” provides the primary motivation for this book. If we are to improve the practice of management, we need to move beyond how-to lists and engage in a more thoughtful inquiry about what we are trying to achieve and what the obstacles are that prevent us from achieving it. I wrote this book, in other words, to help you become a better boss, but don't expect any simple bullet-point lists of things to do. If being a good manager was as simple as following a list of instructions, anyone could do it!

Building A Better Business

There is also a secondary motivation for this book, namely a concern for the overall success and welfare of large business organizations. As I write this in 2012, we face a very uncertain economic future. While the macroeconomic story is the one that gathers most of the headlines, I believe a lot of the problems of the last few years can be attributed to failures of management and leadership in our large companies.

The financial services sector has, not unreasonably, attracted most of the negative attention. Whether the offence is manipulating Libor, laundering money in Mexico, mis-selling pensions, or rogue trading, the cause is always some sort of underlying deficiency in governance or culture that makes the company in question prone to poor decision-making. But plenty of other sectors have also been fingered in the last couple of years – BP's oil spill was condemned as an “overarching failure of management,” Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation was found to have “failed to exercise proper oversight” following the phone-hacking scandal, and pharmaceutical company GSK was fined $3 billion for unethical drug-selling practices2.

In these and many other cases, bad management is indeed to blame. But it is not worth just pointing the finger at the CEO. Typically he takes the hit, as he should, but the problems of a deficient culture or governance system usually stem from decisions made many years earlier. In fact, I would argue that many of the management failures we are seeing today can be traced back to an “industrial era” model of management that is no longer fit for purpose. This model – with its emphasis on coordination through formal rules, hierarchical decision-making, and extrinsic rewards – worked well for many years, but is ill-suited to today's fast-paced, knowledge-based business world.

My previous book, Reinventing Management, focused on these big picture issues. It described how executives can challenge these deep-seated assumptions about how large organizations work and how they can devise new and better ways of working.

This book tackles the same problems from the other direction, that is, by focusing on the choices each of us makes, every day, about how we get our work done. The goal, essentially, is to reinvent the practice of management one person at a time. If each one of us becomes more effective in our managerial work, we don't just improve the working lives of those around us, we also become agents of change for this broader endeavour as well – to build better businesses.

The Way Forward

The central idea in this book is that we can all become better bosses by starting with a more realistic set of assumptions about the challenges we face in the workplace. There are three problems with the standard advice that is offered.

First, it is usually offered from the perspective of the person doing the managing. Most management books and articles are written by successful executives looking back on their careers, or by academics or consultants who have interviewed or advised these same executives. We get a view of how these individuals think and how they achieved what they did. But it is an incomplete story, because it doesn't give a voice to the people being managed – the employees through whom the manager achieved his or her objectives.

Second, it starts from a very rational view of human nature. Google is a company of engineers where data is king. So not surprisingly, their approach to improving management in the company is to see what the data says and to codify the results of their analysis in a way that everyone can understand. Google is hardly alone in this – most large companies have carefully developed lists of management “competencies” and most books on management have recipe books for aspiring managers to follow. But this rational perspective is a gross simplification of reality. There is now a great deal of evidence that we often behave in an unpredictable and nonrational manner, and often in ways we don't even realize.

Third, it assumes that the work of management is happening within a reasonably sensible organizational environment, where objectives are clear, decisions are implemented, and rules are followed. Again, though, we know that many organizations are not remotely reasonable or sensible. People pursue their own pet objectives, they subvert decisions, and they bend the rules. Managers often end up succeeding despite the system, not because of it.

Given all these realities, is it a surprise that the standard advice goes unheeded? Or fails to make a lasting impression on the way we work?

In this book I put forward a perspective on management that starts from a very different set of assumptions.

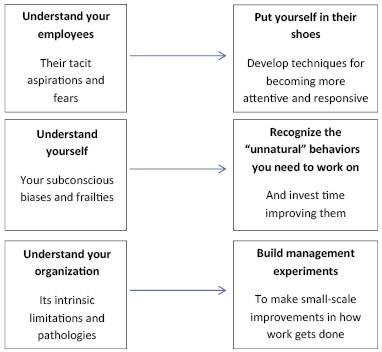

First, and most importantly, I take an employee's eye-view of management. I focus on the needs, motivations, and fears of those working on the front lines of their companies, and ask them what they are looking for in their managers. I examine cases where managers have completely misunderstood the needs of their employees, and have paid the price, as well as cases where they have done an exemplary job of seeing the world through the eyes of those doing the work. This perspective suggests some important new techniques for becoming more attentive and helping our employees to do their best work.

Second, I encourage you to look in the mirror and to confront the biases and frailties that are preventing you from being a really good manager. I show that, for most of us, being a good manager is an “unnatural act” – something that we can learn to do, but only with a lot of deliberate effort. By understanding the three primary areas of tension between our subconscious instinct and our rational mind, we can become more effective at making the right choices when it really matters.

Third, I rethink the role of the individual manager when the organization he or she works for is dysfunctional. I describe the typical pathologies and limitations of large companies and some of the coping strategies that managers use to get things done despite the structure. I also introduce the notion of active experimentation – the idea that you can make conscious but low-risk changes to the way work gets done within your own part of the company.

These three perspectives are summarized below and they provide the overall structure for the book.

Who Is the Book for?

As you should have gathered by now, there are no “silver bullets” for becoming a better boss; no hard-and-fast rules for improving the practice of management. So I am not going to fall into the trap of providing you with a how-to list that summarizes all these ideas. Good management has an analytical component – the folks in Google aren't crazy – but it is mostly about building deep expertise in relating to other people. Like improving our golf swing, we become better managers through practice, feedback, and reflection. And like trying to lose weight, we become more effective when we have got to grips with our own biases and frailties as human beings. So while there are no silver bullets, there are plenty of little tricks we can play on ourselves, and plenty of exercises we can try that will help us develop the expertise we need to succeed.

I have three types of reader in mind for this book:

- You as a manager of others. The book is all about the things you can do differently – to give you a new outlook on your work, to help you reflect on your own biases, and to force yourself out of your comfort zone.

- You as an employee. This book will help you understand why your manager isn't as helpful, articulate, or forgiving as you think he or she should be. And it will also help you to manage him or her more effectively. It is sometimes said that you get the manager you deserve: I don't entirely buy that, but I do believe you have some degree of freedom to help your manager do the job better.

- You as a manager of other managers. Many of the obstacles to good management discussed in this book are not set in stone. If you want your own people to become more effective in their work, there are plenty of things you can do to facilitate their improvement.

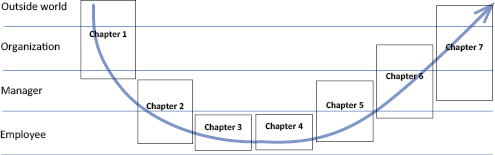

The book is in two main parts. The first part provides the motivation and background for the core ideas in the book. I show how important it is to take management seriously (Chapter 1), I sketch out the key dimensions of management and where it usually goes wrong (Chapter 2), and I take a deep dive into the worldview of the employee (Chapter 3).

The second part provides a detailed discussion of the three alternative perspectives: a re-interpretation of management through the eyes of the employee (Chapter 4), an exploration of our own biases and frailties and how we can overcome them (Chapter 5), and a discussion of the use of active experimentation to overcome the limitations and pathologies of the organizations we work for (Chapter 6).

The final chapter (Chapter 7) looks to the future, to make sense of how technology and other forces are changing the practice of management. Taken as a whole, the flow of the book represents an arc, from the “big picture” concerns addressed in Chapter 1, down to the worldview of the employee and manager, and then back up to the big picture again.

Notes

1 Google's Quest to Build a Better Boss, Adam Bryant, The New York Times, March 12, 2012.

2 The words in quotations are taken from news articles: see the Financial Services Authority report on the collapse of RBS, www.fsa.gov.uk; the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, Chief Counsel's Report, Chapter 5; the quote about Rupert Murdoch from www.newscorpwatch.org.