7

The Future of Management?

My purpose in writing this book has been, simply, to help you become a better boss. By understanding the way your employees think, your own biases and frailties, and the inherent limitations of the organizations in which you work, you should be better positioned to develop strategies and tactics to help your employees do their best work and to get things done yourself. My guidance throughout has been pragmatic – based on a view of how the business world works today, rather than how it might work in a theoretical or idealized world.

This final chapter takes a slightly different approach, by considering how the world of work might change in the years ahead and whether these changes make your job as a manager easier or harder. We all know there are important technological, social, economic, and political changes afoot, and it is important to develop a point of view on what their consequences are likely to be for the type of work we do as managers.

Forces that Shape Our Choice of Management Model

It is useful to have a framework for discussing the way management is changing. Here is one way of looking at it, building on my prior book, Reinventing Management.

The work of management can be broken down into four dimensions: how we coordinate activities, how we make decisions, how we set objectives, and how we motivate employees. The first two are the “means” by which we get things done and the latter two are “ends” for the organization and for individuals respectively. For each of these dimensions, we can identify a traditional set of management principles that have their roots in the model of management that was developed during the industrial revolution: coordination was achieved through bureaucratic rules and procedures, decisions were made through hierarchical control, objectives were set through alignment around the needs of owners, and motivation was focused on extrinsic factors, principally money.

We can also identify a set of alternative management principles that have emerged over the last few decades: coordination can be achieved through emergence or self-organization, decisions can be made through collective wisdom, objectives can be set through the principle of obliquity (i.e., by aiming at one target, you often hit another one), and motivation can be based on intrinsic factors, such as achievement, recognition, or self-actualization.

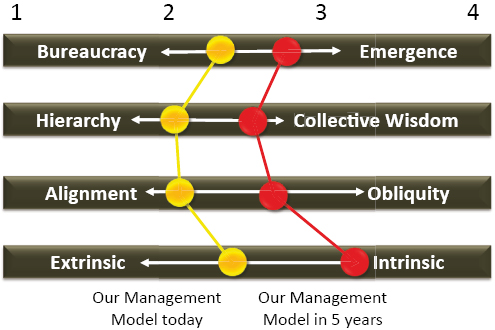

The key idea with this framework is that a company can define its own management model, based around its chosen positions on each of the four dimensions. While many large, traditional companies gravitate to the left side of the framework (see Figure 7.1) and many newer and smaller companies gravitate to the right side, there is nothing inherently right or wrong about these choices. Rather, the position your company takes should reflect its chosen position in the market and the beliefs of the people running the company about its distinctive value proposition.

Figure 7.1 Management Model Framework

I often use this framework in seminars with executives and I take them through the following exercise. I ask them, first, to plot how they would position their company today on each of the four dimensions. Then I ask them to plot where they would like to see their company positioned five years from now. Figure 7.1 shows the average scores I have received for this exercise.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of respondents position their “wanted” position five years from now to the right of their “current” position, and typically by quite a long way – a whole point on a four-point scale. I then ask them, if we went back and asked the same questions again five years from now, where would their companies actually be positioned? Almost without fail, people say they would be “stuck” on the white dots, that is, in the same place as they are today. Of course, I cannot prove this is true, but it is remarkable how consistent and widespread the view that there is unlikely to be very much change.

So what is going on here? After a spirited debate about the factors that are preventing their companies from changing, most groups come around to the following view. There are, in essence, powerful forces pulling in both directions, that is, to the left (inertia) and to the right (change). But they are rather different types of forces. The forces pulling to the left are things that managers have little control over – external regulation, a weak economy, labor unions, the overall size and age of the company, and so on. The forces pulling to the right include the potential offered by social and technological change, and also the courage and leadership skills of the people running the company. In essence, these forces tend to cancel each other out over time. While companies frequently try new things, and sometimes succeed in pushing their management model towards the right side of the framework, the benefits are often short-lived. The company gets into trouble, or a recession looms, or new regulations are brought in, and its management model gets pulled back again, towards the rather traditional but well-understood model on the left-hand side that we all recognize.

Clearly there are limits to how much insight can be gained from a simple framework of this type, but I think it serves us well for a discussion of the ways management might change in the future. In this chapter, we will consider three broad categories of trends (technological, social, and economic/political) and for each one we will use the framework to discuss some important questions: How are these trends affecting the world of work, and the nature of management work in particular? Do they make our jobs as managers easier or harder? And do they require us to change our skillsets, our attitudes, and our behaviors?

Technological Change: Web 2.0

The twin engines of technological change – processing power and connectivity – are continuing to revolutionize many aspects of our working lives. Using my management model framework (Figure 7.1), technology is clearly making it possible for coordination of activities to take place through less bureaucratic methods, and for decisions to be made with much greater involvement and input from people across the organization.

Many commentators use the term Web 2.0 as a shorthand for an important qualitative shift in how technology is influencing work. If the first generation of the Internet (Web 1.0) was a one-way flow of information on to your laptop computer, the second generation (Web 2.0) is a two-way conversation in which you, the user, are also a contributor. For example, if you have ever posted a review on Amazon, or commented on a blog, or provided a vote, link, or tag on something you have read, then you have contributed to the organic, fast-evolving world of Web 2.0. The Internet is no longer a vehicle for transmitting information to a large audience; it is now a medium for sophisticated forms of interaction and exchange. Open source software organizations such as Linux and Apache, for example, have succeeded in creating high-quality software products, as good as anything Microsoft or Google has to offer, through the voluntary coordinated efforts of thousands of people who have never met.

So it goes without saying that Web 2.0 is enabling more effective lateral coordination between people and is contributing to a more bottom-up approach to decision-making. But my focus in this book is much narrower: I want to know if these technological advances are changing the nature of work that you do, as a manager of others.

Let's consider a specific example. Most business people today have tried microblogging sites such as Yammer (now owned by Microsoft), which seek to bring the free-flowing style of interaction offered by Facebook to the corporate world. These are password protected sites where people in the same company will share views on topics of interest, but they are hosted externally, so they don't get suffocated by the rules and standards that Corporate Intranets often impose.

The IT services company, CapGemini, is a very active user of Yammer1. Its former CTO, Andy Mulholland, describes it as a means of decentralizing the information flow at CapGemini to create greater collaboration from the outside in. The consultants “at the edge” use it as a way of posing questions and sharing their insights, and because they encounter new challenges and opportunities before those at the center, it becomes a useful knowledge-sharing tool. In addition, the company has experimented with “YamJams,” webcasts where Yammer works as a back channel for people to hold conversations while the executive concerned is presenting or to send comments in real time. The CEO is known to regularly go on to Yammer and check out who the top thread followers and creators are and what they're discussing.

Problem-solving is also a major area of usage, with people asking for support or help in tracking down a colleague or information resource. One thread starts with the request: “We need more Level 3 and 4 Certified Software Engineers.” Other threads revolve around building communities of interest on a particular topic, such as “We are working on Technovision 2011 (a thought leadership publication). What Technology trends should we absolutely not forget to include?”

There are three groups of users. The hugely active group comprises around 50 people who are managing communities and ensuring that Yammer is working all the time. There are around 300 regular Yammer users, and then there are the thousands of “listeners,” those users who perhaps use Yammer for a specific purpose, to follow a thread about a topic that resonates with them2.

So how does microblogging change the work of management? CapGemini uses Yammer for aligning activities, problem-solving, information-sharing, and providing clarification. Now think about the things you do for a living as a manager – and you quickly end up with a pretty similar list. Yammer and related technologies are increasingly being used to provide the support and input that employees used to get from their managers.

This frees up managers, in turn, to spend more time on the real value-added work – such as motivating their employees, structuring their work to make it more engaging, developing their skills, securing access to resources, and making linkages to other parts of the organization. It wouldn't be stretching the point too far to note that all the key things we ought to do as managers “to enable our employees to do their best work” are still required in the world of Web 2.0, whereas all the things we used to do, because they helped us to retain control, are now done quicker and more effectively through technology.

Of course, we have heard parts of this argument before. The original boom in IT usage in the corporate sector, some 30 years ago, led to predictions of the demise of the middle manager, because the technology would enable senior executives to communicate seamlessly with their front-line managers. Today's new technologies are partly just pushing these trends further forward, but they are also encouraging a much greater amount of interactivity in corporate communication than was possible before, making the information flow richer and more readily interpreted.

The bottom line is that technological change is clarifying our role as managers. Warren Buffett is famous for saying that it is only when the tide goes out that you can see who is swimming naked, and the same metaphor applies here. When employees can get all the basic support they need for their work through microblogging sites, rather than through their line manager, the real qualities of the line manager are exposed.

Social Changes: Generation Y and Transparency

There are many social changes underway that are shaping the business world: the ageing population, a greater focus on health and well-being, awareness of sustainability issues, female empowerment, a greater emphasis on transparency in society, and so on. Again, the focus here is not on the way these trends are shaping business as a whole. Rather, I am interested in how, if at all, social changes are influencing the nature of managerial work. I suggest two are particularly relevant in this regard.

First, is the emergence of Generation Y, those people born after 1980 who are now entering the workforce in significant numbers. It is frequently argued that these individuals bring with them a different set of expectations about work and a different set of skills, in comparison to Generation X and the Baby Boomers. For example, it is suggested that they want freedom in everything they do; they love to customize and personalize; they are the collaboration and relationship generation; they have a need for speed3. It is open to debate whether these are life-stage, rather than generational, differences, but even the most skeptical observers recognize that Generation Y is far more technology-savvy and able to multitask than Baby Boomers like myself. Here is one data point: one study showed the Generation Y employees who were more committed to the companies they were working for were also the ones who were spending more time online using Facebook and other social networking sites during their working hours4. Far from being a distraction, Facebook usage was seen by these employees as an integral part of their modus operandi at work.

How does our work as managers change when our team is mostly made up of Generation Y employees? The “good news” is that these employees were brought up in an era of prosperity and safety, and they have no memory of the period of industrial strife that many Baby Boomers experienced in the 1960s and 1970s. Recall the stories I recounted in Chapter 3 about intransigent and cynical workers – those were stories from the Baby Boomer generation, and they would not resonate at all with a typical Generation Y worker.

The “bad news,” on the other hand, is that Generation Y employees are more tolerant of uncertainty. They are less likely to put up with a dull job or a bad boss, because societal norms have moved away from the notion of a job for life, and because the marketplace for jobs is more efficient than it has ever been. Turnover rates are on the rise: in the fast-food sector, it is often greater than 100% per year, and rates of 30–50% per year in other fast growing sectors, such as IT services, are not uncommon.

Again, the net effect of this trend is that your qualities as a manager are more exposed than ever before. I don't believe Generation Y employees are any more or less ambitious than previous generations, but they are more willing, and more able, to change jobs when things aren't going their way. To the extent that you, as their boss, want to get the best out of them, you need to be more thoughtful about the type of work you give them and the conditions in which they are expected to do it.

The other social trend to consider here is the dramatic increase in transparency, at all levels. From geopolitical issues (the Arab Spring, Wikileaks) to business scandals (phone hacking at News International, fraudulent accounting at Olympus) to debates on corporate values (Google, Facebook), the common theme is that nothing is truly secret any more. Technological advances make it much easier to gather, assimilate, and distribute information than before and society increasingly accepts that higher levels of openness and transparency are OK. Of course, this shift is not happening without debate, and indeed many people are worried about how much Google or Facebook know about us, but the broad trend here is taking us in one direction only, namely towards greater transparency. People are asking institutions of all types, from government to church to corporations, to be more open about their actions, and to take greater responsibility for the consequences of those actions.

The point here is that social change is legitimizing the increasing transparency that is underway in the business world. On many dimensions of management, companies are becoming more open in their activities. For example:

- Software companies like Red Hat and Atlassian have “open strategy” processes where all employees are invited to contribute to the development of the company's strategic priorities.

- The IT services company, HCL Technologies, has an “open” 360-feedback process, where a manager's feedback from those around him or her is posted online for everyone to review.

- The UK consultancy, Nixon McInnes, has open salaries: everyone knows what everyone else earns and the salary review process starts with the employee proposing how much more he or she should make next year.

These sorts of initiatives have important and fairly predictable consequences for how managers conduct themselves. Greater transparency means that you as a manager can no longer hide behind a wall of “privileged” information. You have to become more tolerant of feedback and you have to become better at influencing others through the quality of your arguments. It is harder work, and typically takes longer, but the potential for higher-quality outputs is greater.

Economic and Political Changes: The Shift from West to East

It goes without saying that economic and political changes are creating new challenges for corporate executives. At the time of writing this book, the big stories were political uncertainty and economic stagnation in Europe, a likely slowdown in growth in China, fiscal uncertainty in the United States, and continuing unrest in the Middle East. With all such trends, there are first-order consequences for business, in terms of demand, regulation, taxation, labor, and so on. My interest here is on the second- and third-order consequences of these changes, in terms of how shifts in the economic and political landscape will affect how companies and individuals operate.

One obvious set of consequences is that managers will need to develop new capabilities. They will have to become better at operating in a “virtual” manner, that is, coordinating teams across multiple time zones and overseeing employees whom they rarely meet face to face. They will also have to figure out how to manage businesses growing at very different rates in different parts of the world. Emotional intelligence, especially in terms of sensitivity to different national cultures, will be more important than ever.

However, there is something deeper going on here as well. If we buy the argument that the center of gravity of the business world is shifting from “West” (North America and Europe) to “East” (Asia), then it is worth considering if we are on the cusp of important parallel changes in the way we think about management5.

Consider how US hegemony – in all respects – is fading. In the years following the Second World War, it dominated the global business world, as the major source of capital, the home of advanced manufacturing, and the source of most major technological developments. It provided the best-quality management education and it was the source of all the latest management thinking.

In today's more complex, plural world, the biggest sources of capital are the large Sovereign Wealth Funds of the Middle East, Russia, and China. Leadership in advanced manufacturing is spread across such countries as Japan, Korea, Germany, and the US. Technological innovation is dispersed across the world. Top-quality business schools exist in every major market. In short, the rest of the world has caught up. North America no longer holds a clear advantage in any of these fields of accomplishment, but with one exception: management ideology.

By management ideology, I mean the basic assumptions we use to talk about the practice and profession of management. The “traditional” management ideology I described above was largely developed by academics based in the US, studying US companies, with a few notable exceptions (e.g., Henri Fayol, Max Weber). Even today, the US hegemony in management ideology endures. The vast majority of faculty at the top business schools in Europe and Asia gained their PhDs in North America. The top management journals, from Fortune to Harvard Business Review, are all based in North America. The top management consultancies, from McKinsey to BCG, Bain, and Booz Allen, all have deep American roots.

One consequence of this dominance is that other perspectives get suppressed. There are strong traditions of management writing in both the French and German languages, but they are being marginalized: the up-and-coming scholars in Continental Europe are increasingly writing for English-language journals, and large French and German companies are increasingly bringing in North American trained consultants and academics to advise them. As for the developing world, there is no better way of proving that you are an ambitious, progressive company, than by hiring “professional” managers and advisors that cut their teeth in the North American system: look at Ambev (Brazil), Infosys (India), Huawei (China), DTEK (Ukraine), or Korea Telecom. The entire business world is seemingly in thrall to the dominant American ideology of management. America may have lost its lead in other areas of business, but it still holds sway in this one, vital area.

So should we expect to see a shift in management ideology away from North America and towards Asia? And if yes, what will it look like?

My view is that such a shift is highly likely, but will take many years to transpire. Using the current measures of what constitutes effective management, the American model is better than what is on offer in other countries6, and at the moment companies in the emerging “BRIC” economies are simply trying to catch up. However, there is no reason to believe that this state of affairs will last forever. Many observers have commented on America's declining influence over the world, and the apparently inexorable rise of China and India. As these other countries come to influence the world of business more generally, we should expect them to also influence the way we think about – and implement – the practice of management.

What might an alternative model of management, built on Asian values and capabilities, look like? One starting point is to think about the differences in national culture across regions. For example, the Anglo-American world is relatively individualistic and it has a relatively short-term orientation. Most Asian countries, in contrast, have a more collective orientation and a relatively long-term orientation. So building on these differences, here are a few thoughts about how management might evolve:

- In terms of objective-setting, why don't we put a greater focus on higher-order purpose or vision, rather than short-term financial returns? And what about giving equal emphasis to multiple stakeholders, rather than focusing singularly on shareholders?

- In terms of coordination, can we imagine putting a greater focus on self-organization and collective wisdom, rather than bureaucratic rules and procedures, as a way of getting things done?

- In terms of outcomes, should we put a greater emphasis on innovation, creativity, and employee engagement, rather than just productivity and efficiency?

These are questions not statements. We know more about the limitations of our existing model than what the alternative would look like, but there is some evidence that these alternative approaches are starting to take hold. For example, a recent book, The India Way, sought to identify the distinctive characteristics of the most successful Indian companies, and it focused on “holistic engagement with employees,” “improvisation and adaptability,” and “broad mission and purpose.” These features, the authors claimed, were inspired partly from ancient writings, such as the Bhagavad Gita, and partly from the experience Indian executives had growing up in the chaotic post-war years7. We can imagine similar books being written on the China Way or the Brazilian Way in the years ahead.

In sum, there are good reasons to expect the dominant model of management to evolve as regions of the world, other than the US, move into the ascendancy. Think back to Figure 7.1 earlier in the chapter: the management principles on the left side, especially those concerned with extrinsic rewards and alignment of objectives, are much more consistent with Anglo-American cultural values than those on the right side. If we expect to see a shift towards greater emphasis on collectivity and long-term orientation, then the right side of the framework becomes a more logical and desirable place to sit.

Conclusion: Making the Right Choices

This brief discussion of trends suggests a consistent theme: the practice of management is becoming both more challenging and more rewarding. Technology is making many of the traditional aspects of management redundant, freeing up our time to do the more value-added parts of our work. Social change is making employees more demanding. Political and economic shifts are exposing us to different models of management that are more long-term oriented and less shareholder-focused.

Using the framework I introduced earlier, we can expect the management model in large organizations to move gradually away from the traditional one based on bureaucracy, hierarchy, extrinsic rewards, and alignment. Gradually is the key word here: the inertial forces pulling us back towards the world we know, and are comfortable with, are strong. But it seems inevitable that organizations will gradually align themselves to the demands placed on them and the opportunities they face.

Managing well is about developing greater awareness of what our employees need, where our own biases and limitations lie, and how our organizations really function. It is about doing what works, rather than what comes naturally, and this requires a considerable amount of self-discipline and personal development.

However, managing well is also about making explicit choices, and these sometimes involve departing from the tried-and-tested models that others are pursuing. I believe the trends outlined here are taking us in one direction only, with our employees and our broader stakeholders all demanding change. The question to ask ourselves, as individual managers and as agents of change within our own organizations, is whether we want to be the leaders or laggards in this process of evolution. We can seek to improve the nature of management ourselves or we can allow others to do it for us.

Notes

1 The CapGemini case was written up in “A Common Thread: Microblogging at CapGemini,” Labnotes Issue 19, www.managementlab.org.

2 To make sure it is used prudently, CapGemini has developed a code of conduct, which starts: Yammer is “a source of instant inspiration to strengthen and empower its members to face their daily impediments and foster the development of international social networks around common areas of interest.”. Importantly, because Yammer is hosted by an independent company, not by a central IT department, no confidential or client-specific matters are discussed.

3 Tapscott, D., Grown Up Digital, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2009, page 35.

4 This research was conducted by You at Work, a leading player in the market for flexible benefits consulting (corporate.youatwork.co.uk). It was reported in: Julian Birkinshaw, Play Hard, Work Hard, People Management, October 30, 2008, page 46.

5 These ideas were first developed in a blog: http://www.managementexchange.com/users/julian-birkinshaw.

6 See: “Why American Management Rules the World” by Nick Bloom and colleagues, http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/06/why_american_management_rules.html.

7 Capelli, P., Singh, H., Singh, J., and Useem, M., The India Way, Harvard Business Press, 2010.