1

Why Management Matters

One of the motivations in writing this book was to tackle the following puzzle:

- Do we know how to generate sustainably high performance in companies? Yes we do.

- Do companies consistently follow this established formula? No they don't.

On the face of it, this seems strange. Surely human nature compels us to seek out better ways of doing things? Surely competition between companies creates a survival-of-the-fittest push for constant improvement? Well, yes it does, but there are also many other forces at work that can frustrate our ability to do what we know to be right. Sometimes these forces prevail, leaving everyone stuck with an inferior model.

The established “formula” for delivering high performance is what I call a people-centric approach to management. It involves hiring talented and motivated people, providing them with the competencies they need to succeed, and – most important of all – putting in place a system of management that enables them to do their best work.

Do you buy the argument that a people-centric approach to management is key to long-term success? When I ask this question in seminars, the majority of people say yes: they intuitively buy the argument. However, when I probe further, it becomes clear that a significant number are more sceptical – they aren't convinced its true, but they figure that investing in people doesn't do much harm and perhaps it is just one of the costs of being in business, so they go along with it. Then there are the cynics, usually a fairly small number of people, who strongly disagree – they think this emphasis on people is misguided or insincere, or perhaps even a Machiavellian way for managers to further their own objectives.

I will get back to the views of the cynics later, in Chapter 3, but for now, I want to concentrate on those in the first two groups. I was in the first category when I started researching this book. I saw the link between investing in people and corporate performance as axiomatic – self-evidently true, but so fundamental that it probably couldn't be proved.

Drivers of Corporate Performance

It turns out I was half-right. When you collect the evidence together, it shows that the axiom is not only correct but is also objectively verifiable. Several recent academic studies have shown that companies with engaged and happy employees outperform those that do not1. There has also been a lot of applied research in recent years, such as the “Engage for Success” movement in the UK, which has drawn similar conclusions2.

One particular study is worth recounting here in detail. A London Business School Professor, Alex Edmans, studied the “Best Companies to Work For” in the United States and focused on their stock market performance over a 25 year period. He showed that “A value-weighted portfolio of the 100 Best Companies earned an annual alpha of 3.5% from 1984 to 2009.” In plain English, this means that if you invested your own pension in these companies, and left it there, you would get a significantly better return – 3.5% per year – than the average fund manager3. Edmans showed, in other words, that not only do these “Best Companies to Work For” have better performance over the long-term than those in the market as a whole but also the stock market fails to pick up on their superior prospects.

Remember, stock markets are supposed to be efficient. If Apple announces a new category-busting product or if Roche gets a patent on a new cancer drug, their shares rise in anticipation of future growth. However, when Fortune magazine announces the annual list of winners in the Best Companies to Work For ranking, the stock market doesn't care. This information just doesn't make it on to the analysts’ radar screens. Implicitly, investors seem to be saying, “OK, so you take care of your employees well, good for you; but we won't be buying up your shares until we have seen how that investment works its way through to the bottom line.”

To say this even more simply, analysts and professional investors don't buy this “soft stuff.” Even with solid evidence that investing in people makes a long-term difference to performance, they retain their sceptical position. As one analyst said, “Costco's management is focused on … employees to the detriment of shareholders. To me, why would I want to buy a stock like that?4”

So why the scepticism? To answer this question, it is useful to go back to economic theory because stock markets are heavily influenced by that body of thinking. For many economists, employees are still nothing more than an input cost. Companies invest in workers in the same way they invest in plant and machinery and technology; they spend as little as they can, they sell their product for as much as they can, and the difference is profit. If this is true, then spending more than you have to on employees is just throwing money away. Of course, this is a gross simplification, and indeed there are many alternative economic theories that recognize the unusual nature of human capital, but old theories die hard, and the aggregate view is still one that treats “intangible assets” like expertise and discretionary effort with suspicion.

Perhaps this is starting to change. An extensive research program led by Professors John van Reenen (London School of Economics) and Nick Bloom (Stanford) over the last decade has sought to shed light on why we see big productivity differences between seemingly similar companies. They show that quality of management is the key – some companies simply use better management practices, in a more consistent way, than others and these practices have a significant impact on productivity and performance. This isn't a surprising finding to those who work in or study the field of management, but it is helping to shape the conversation among economists about how companies really work.

Regardless of what investors and analysts think, the key point is that there is a well-established formula for achieving long-term corporate success, and it is about investing in people and fostering a high level of employee engagement. To be clear, these effects are true in aggregate, but not in every specific case, and there are many other drivers of corporate success as well. But these are small caveats; the overall body of evidence is still sufficiently strong to make investing in people a smart strategy for your company, and investing in people-centric companies a smart strategy for your pension.

Quality of Life Considerations

So much for the investor or owner's perspective. What about the broader view? How does a people-centric approach to business affect society as a whole? The evidence here is equally persuasive. There have been many research studies showing, for example, that engaged employees have lower levels of absenteeism, high levels of overall well-being, and even lower incidences of disease5. Moreover, the principle of employee well-being is as old as the field of management itself. Students of business history are familiar with the concept of Corporate Welfarism from the 1880s6 and the Quality of Work Life movement in the 1950s.

Today, there is currently a huge amount of interest in happiness and positive psychology. Studies have ranked countries by how happy their people are (top of the list: Denmark)7. Policy-makers have put programs in place to foster more positive attitudes at work and home. In the UK, Prime Minister David Cameron has picked up on this trend, by launching an initiative to start measuring National Well-being alongside traditional economic measures such as GDP. He said we need to “start measuring our progress as a country not just by how our economy is growing, but by how our lives are improving; not just by our standard of living, but by our quality of life.8” (for more information on this initiative, see the website www.engageforsuccess.org).

Of course there are many factors that shape our quality of life and the world of work only represents one part of the story. But for those of us in full-time employment, the quality of our working lives has a huge impact on our overall well-being and indirectly on the well-being of our families. Think of it from the employer's perspective. If your employees spend 40–50 hours a week in the office, you owe it to them to make it as worthwhile and pleasant as possible – not just because that is morally the right thing to do but also because happy employees are healthier and more productive.

Again, the evidence suggests that a people-centric model in the corporate world isn't just good for performance; it is also good for the people working in that company and society as a whole. Now, I realize that this sort of “win-win” story makes people a bit suspicious: surely there is a catch? Surely there is, at least, an opportunity cost to this sort of investment?

Well, there might be, but the truth is, we don't know. The reason we don't know is that despite all the evidence that this people-centric approach is better, there are actually remarkably few companies that have implemented it on a consistent basis.

The Rhetoric–Reality Gap

Greg Smith caused quite a stir in March 2012 when he wrote a scathing op-ed in The New York Times, “Why I am leaving Goldman Sachs.9” He said the company was morally bankrupt and that its culture of teamwork, integrity, and humility had been lost.

I don't have the inside story on what Goldman is really like, but Greg Smith's description sounds remarkably like every other investment bank on Wall Street or in the City of London. It is the oldest story in the book: when big bonuses are on the line, people become greedy, they look out for their own interests, and collaboration, integrity, and humility go out the window. The culture in these banks is individualistic and aggressive. Bad management is tolerated. People are expendable.

Whether accurate or not, my point here is a simple one, namely that the world Greg Smith described in his New York Times article was exactly the opposite of what Goldman Sachs says about itself. The company website says, “Our people are our greatest asset. We say it often and with good reason … at every step of our employees’ careers we invest in them… our goal is to maximize individual potential.”

So if we want to get a fix on how people-centric companies really are, we can start by entirely disregarding any public statements they might make. A much better approach is to ask employees, preferably in an anonymous way, about how happy or engaged they are, or how good their managers are. It is also useful to gather objective data about, for example, levels of employee turnover or cases of harassment and bullying. Once you get this sort of information, the story that emerges is not a happy one. Here are some examples of recent studies:

- Human resource consultancy Towers Perrin (now Towers Watson) measures employee engagement levels across countries and sectors. On an aggregate level, its 2003 data showed that 17% of the sample were highly engaged, 64% were moderately engaged, and 19% were disengaged with their work.

- A poll of workers in the UK commissioned by the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) in 2008 found that only 43% of employees were fully engaged in the work they were doing10.

- The UK's Chartered Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD) does a quarterly “employee outlook” survey. In July 2012, they found that only 38% of employees were actively engaged at work, with 59% neutral, and 3% disengaged. While respondents felt their managers mostly treated them fairly (71%), less than half were satisfied with the level of coaching and feedback they received11.

The picture that emerges from these and other studies is pretty clear. There are some very well-managed companies out there with highly motivated and engaged employees. There are also some dire companies with miserable employees who are investing more time looking for a new job than doing the work they are paid for. The vast majority of companies are stuck in the middle, no doubt trying hard to improve their people-management practices but without the buy-in they need to make it a real priority and without the results to show for it. Such companies typically have pockets of excellence, but a great deal of mediocrity as well.

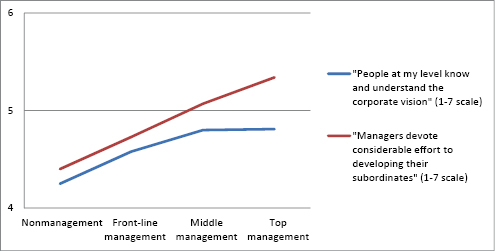

There is, in short, a rhetoric–reality gap between the words and policies of top executives and the experiences of front-line employees. Figure 1.1 provides an illustration of this gap, from some research I was involved with12: it shows employees answer the same questions less positively the lower you go in the corporate hierarchy.

Figure 1.1 The Rhetoric–Reality Gap: employees have very different views on corporate practices, depending on where they sit in the company

This gap causes problems in a couple of ways. First, it creates confusion: when employees see a disconnect between the stated priorities of the company and the decisions that are enacted on a day-to-day basis, they don't know where to focus their efforts. Second, it breeds cynicism: an underlying sense that top executives are out of touch and therefore not to be fully trusted.

The presence of this large rhetoric–reality gap opens up a couple of important questions. First, why is the gap so large? If the evidence favoring a people-centric approach to management is so strong, why don't companies actually do what they know they should? Second, what can we do to close this gap? What steps can we take – as individuals and as management teams – to make a real difference to the way our companies are managed? In the remainder of this chapter, and in Chapter 2, I will suggest a way we might tackle this first question. The second question then motivates the remainder of the book.

Explaining The Puzzle

Let's return to the puzzle I introduced at the beginning of this chapter. If a proven better model exists, wouldn't we expect people to gravitate towards it? Well, yes we would, but it doesn't always work out that way. Sometimes an inferior model wins out and sometimes the better model never takes off.

Consider that old favorite, the battle for supremacy in the personal computer industry. Apple's operating system and user interface were vastly superior to anything IBM or Microsoft had to offer in the early 1980s, and even today most people would still agree that Apple's operating system and user interface are second-to-none. However, Apple's worldwide market share in the PC/laptop industry is stuck at around 5–10%, well below that of leaders like HP, Dell and Lenovo.

Another classic story, though from a completely different context, is a study reported by Everett Rogers in his book The Diffusion of Innovations. Health workers in Peru were trying to persuade villagers to boil their water to reduce illness, but these villagers didn't understand the science behind boiling water, they were sceptical of outsiders telling them to change their ways, and boiling water was stigmatized as something only unwell people would do. The two-year campaign was considered largely unsuccessful.

Under certain circumstances, then, the better way of doing things doesn't take off. Sometimes, as in the Apple–Microsoft case, the problem is simply that we get locked into a suboptimal way of working and the costs of changing (throwing out our Windows PC, learning how to use the new software) outweigh the potential benefits (a slightly better user experience). At other times, and the Peruvian villagers illustrate this nicely, the problem is a lack of buy-in to the new way of working: lack of understanding of the potential benefits, distrust of the people selling it to us, and concerns about how risky or expensive it will be to implement.

These examples help to shed light on why we don't see widespread adoption of the proven people-centric model in the corporate world. As with the PC industry, companies are “locked” into an old model of management that views employees as input factors and they are saddled with traditional beliefs and processes that reinforce that view. As with the Peruvian villager story, companies are suspicious of the “better” model that involves investing in and empowering people. They are sceptical of the outsiders – the consultants and academics – pushing the new model and they aren't convinced that it will work for them.

Why Companies Struggle to Change

To test out these ideas, some colleagues and I conducted a survey, asking managers from around the world for their views on the future of management13. First, we asked where the biggest gaps were – between how important a set of managerial challenges were and the amount of progress their companies had made. The biggest gaps were in how we make sense of our world and relate to each other: the need to Retrain Managerial Minds, Further Unleash Human Imagination, Depoliticize Decision Making, and Reduce Fear, Increase Trust (see Box 1.1: The Biggest Challenges in Management). So no real surprises there – our respondents told us, in essence, that it is difficult to fully make sense of and buy into this new way of working.

We asked respondents to rank a series of “moonshots” in terms of the importance that their organization makes progress on them (where 1 = unimportant, 2 = important, 3 = essential). We also asked respondents to evaluate the amount of progress their organization had already made on each challenge (1 = little, 2 = modest, 3 = substantial). By calculating the difference between the two scores (importance less progress made), we were able to draw up a list of the most critical challenges facing management today. These are the areas where the biggest opportunity for management innovation exists. The top five were as follows:

Why did these five come out on top? Because employees can relate to them at a very personal level. Fear and trust are sensations we feel on a daily basis; we experience the fallout from politically motivated decisions directly and most of us have plenty of latent creativity and passion that doesn't find an outlet in the workplace. The odd one out was the perceived need for holistic performance measures, which was perhaps shaped by our desire to make sense of the financial crisis (the survey was conducted in 2009).

The second part of the survey asked respondents what the biggest barriers to change were. In other words, we were asking them why the rhetoric–reality gap existed. After grouping their answers into categories, we ended up with the following as the biggest barriers:

- Limited bandwidth: not enough time, too few resources (19% of all responses)

- Old and orthodox thinking (15%)

- Disincentives to act: fear of change, executive self-interest (14%)

How do we interpret these answers? In my view, the managers in the survey were saying: we would love to pursue these exciting challenges, but we are already running at full pace, with no slack; our colleagues and our bosses have no interest in disrupting the status quo; and we are so stuck in old-style thinking that we cannot imagine an alternative. It is almost a cry for help.

Going back to the Apple–Microsoft analogy, they are saying that they are locked into a badly wired operating system. They would love to move out of it, and into a better system, but the switching costs are too high. So while there may be some problems of a lack of understanding of the better alternatives out there, the bigger problem appears to be a lack of capability to make the necessary changes.

When I speak on these issues, I often get the audience – typically mid/senior executives in large companies – to offer their views. Why, I ask, is the world of management stuck with an inferior model when we have such solid evidence that there are better ways of working out there? The audience typically echoes many of the points noted above, but they also bring some additional insights.

The first is that a people-centric approach to management is systemic. You can't just train people in new ways of working, or measure their performance differently, or change the reward system, or hire on attitude rather than skill, or change the promotion criteria: you have to do all these things. Each one reinforces the other, and so it is only by creating the “bundle” of people-centric systems that you get the improvement in performance that is being sought14.

The second is that a people-centric approach to management is a long-term investment. Behavior change takes time, so even if all the necessary changes are put in place, the desired performance improvement is likely to kick in several years later. For many executives, a 4–5 year return on investment is simply too slow to be worth doing – they know they will have moved on to their next challenge before the results are through.

Finally, the people-centric approach to management is fragile. It assumes people are competent and committed to the company's goals and it gives them a lot of discretion in how they act. But it only works if everyone plays along. For example, you might want to give your team a lot of space to experiment with new ways of working, but that only works if your boss is also prepared to give you the freedom to fail. Or consider the case of a single rogue trader who cheats the system: he loses his job, but everyone also suffers because the rules get tightened up company-wide to avoid the same thing happening again.

In fact, the more you think about it, the easier it is to understand why we have made so little progress towards this demonstrably better people-centric model of management. The inertial forces in our complex organizations are very strong and it seems that no amount of effort can fully overcome them.

Surely some progress has been made? What about, for example, the “Best Companies to Work For” that were mentioned at the beginning of the chapter? Yes, indeed. So, as we look at the entire organizational landscape, there are certainly companies that have implemented various forms of people-centric management. Indeed, without such cases we wouldn't be able to say that a proven better model exists. A closer look at these “outlier” cases is instructive. They can be put into three groups:

The trouble with this list is the following. Most of Group 1 will end up gravitating towards the traditional model of management as they grow, because it is safe, established, and predictable. Some will end up as Group 2 companies, but these are hard to learn from, because they have always operated with their unusual model. They are also susceptible to losing their distinctiveness, especially when there is a change in leadership or their ownership model changes (e.g., through a stock-market listing). Group 3 companies, while impressive, are few in number and always at risk of being sucked back towards the traditional model.

To summarize the argument so far: there is a proven “better way” of managing, one that involves putting people first and creating an environment in which they can do their best work. However, very few companies have implemented it because it is difficult to do, requires long-term investment, and makes investors nervous.

How you interpret this statement depends on your outlook on life. If you are a pessimist, you will focus on the barriers to change and the lock-in problem, and you will likely conclude that this people-centric model will never take off. If you are an optimist, you will point to the list of outliers, the companies that have lit up the way forward, and you will conclude that we are on the cusp of dramatic improvements in the way companies are managed.

I am a pragmatist: I think fundamental improvements in management are possible, but I expect progress to be slow and that it won't happen without strong leadership. I have spent a lot of time over the last five years working with companies on this exact challenge. I know how difficult it is to make positive and lasting changes in how companies are run. But I have also seen glimpses of success, and certainly enough to make the effort worthwhile.

Why Individual Managers Struggle to Change

This chapter has focused on the company as a system: a community of individuals working together through established rules and procedures to achieve a common objective. I have argued that this system is often so complex, and its elements so tightly interwoven, that it becomes inert, even in the face of compelling evidence that it should change.

However, we can also pursue a similar line of argument at the individual level. If our bureaucratic management systems help perpetuate a broken model of management, perhaps our own individual beliefs, motivations, and interests are also playing their part?

Here are a few simple questions to get you thinking. Do you invest your time in things that help others to succeed? Do you invest in projects that will help the company in the long run, even if you won't be around to get any credit for their success? Are you prepared to try out a new way of working that may fail, even if you risk looking foolish?

Most people would like to answer yes to these questions – but the evidence says that most of us actually do these things pretty rarely. For the most part, we prefer to invest in things that help us meet our own goals, provide short-term success, and with as little risk as possible. This, in a nutshell, is the real reason why change is so hard in companies. Good management goes against many of our natural predispositions as individuals, and as a result we often behave in ways that make progress difficult.

If we want enduring change in how companies work, we need to tackle the problem from both sides: we need to rethink the “architecture” of management to engage and motivate individual employees, but we also need to rethink the “practice” of management, one person at a time, to ensure that we are all acting in ways that support these broader changes. This latter task is what the book is all about.

Before we can get into rethinking the practice of management we need to figure out what good management looks like in the first place. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Notes

1 For example: (1) Harter, J.K., Schmidt, F.L., and Hayes, T.L., Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis, Journal of Applied Psychology, 2002, 87(2): 268–279; (2) Fulmer, I.S., Gerhart, B., and Scott, K.S., Are the 100 best better? An empirical investigation of the relationship between being a “great place to work” and firm performance, Personnel Psychology, 2003, 56(4): 965–993; (3) MacLeod, D. and Clarke, N., Engaging for Success, 2009, http://www.bis.gov.uk/files/file52215.pdf.

2 http://www.engageforsuccess.org/.

3 Edmans, A., Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 2011, 101(3): 621–640.

4 Quoted in Edmans, op cit, page 1.

5 See, for example: (1) Nyberg, A., The impact of managerial leadership on stress and health among employees, Doctoral Thesis, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, 2009, ISBN 978-91-7409-614-9; (2) Gillet, N., Fouquereau, E., Forest, J., Brunault, P., and Colombat, P., The impact of organizational factors on psychological needs and their relations with well-being, Journal of Business and Psychology, 2011, DOI: 10.1007/s10869-011-9253-2; (3) Crabtree, S., Engagement keeps the doctor away, Gallup Management Journal, 2005.

6 Mol, M. and Birkinshaw, J.M., Giant Steps in Management, FT Prentice Hall, London, 2008.

7 Levy, F., The World's Happiest Countries, Forbes.com, July 14, 2010.

8 David Cameron's speech on November 24, 2010, www.number10.gov.uk.

9 Smith, G., Why I am Leaving Goldman Sachs, New York Times, March 14, 2012. Smith also published a book on this same topic which came out in late 2012, though it did not create the same level of interest.

10 TUC, What Do Workers Want?, YouGov poll for the TUC, August 2008.

11 CIPD Employee Outlook survey, Spring 2012, www.cipd.co.uk.

12 These data are taken from a current research project by the author.

13 This survey was conducted by myself and Gary Hamel, based on the ideas Gary developed in a Harvard Business Review article, Moonshots for Management, February, 2009.

14 Academic evidence for this point is strong. For example: McDuffie, J.P., Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 1995, 48(2): 197–221.