Introduction

This chapter describes procurement steps and options for an individual project or programme that delivers a new or enhanced asset (referred to as either ‘project’ or ‘projects’) for a client organisation. The ‘Improving Infrastructure Delivery: Project Initiation Routemap Handbook’1 from HM Treasury defines procurement as:

In the first instance, understanding the designation of a client organisation that is funding a project (between either public or private sector) can dictate the array of controls associated with a procurement process, resources and structure of the client organisation. For example, with a privately funded project such controls would include internal and external audit requirements and a review by funding partners, whereas a publicly funded project will also need to consider compliance with procurement regulations2 (in order to comply with European Union procurement directives3), in addition to adhering to more specific central or local government requirements.

It is a common belief that mandatory adherence to the Public Contracts Regulations4 (referred to as the ‘regulations’), underlying European Law and Council Directives generally results in a longer procurement process. However, it is also worth analysing the disruption caused by incomplete or poorly defined requirements supplied by the client organisation together with changing business-critical outcomes rather than purely blaming the process.

Irrespective of the actual designation of a client organisation, when procurement is treated as an integrated function within the other project team disciplines it can be an effective tool, provided it considers the following underlying structure:

- 1 Analysis: an explanation of the nature of the challenge, condensing complexity into a simpler understanding of key issues that must have clear alignment to attaining each project’s business-critical outcomes.

- 2 Strategy: an overall strategic procurement approach chosen to cope with or overcome the obstacles identified through the analysis that can flex in response to any internal or external influences.

- 3 Actions: coordinated procurement activities that are integrated with the overarching project programme that supports the accomplishment of the strategy.

Of course the relative complexity and size of each project, together with the nature of business-critical outcomes, will dictate the depth and level of intricacy required to develop and implement a successful procurement strategy.

Why should procurement be considered at the start of the project?

A client organisations’ opportunity to select an effective procurement strategy that best fits with its own capabilities and has the highest probability of delivering successful outcomes is greatest at the outset of a project ie the appraisal stage (Stage 0 of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013).

As a project develops, apart from the passage of time, inevitably decisions are also required that can influence – sometimes unintentionally – the achievement of business-critical outcomes. The later a procurement strategy is properly considered in the work stage cycle, the less effective that strategy becomes as a tool and more likely it would have the characteristics of a mechanistic, process-led activity that would add little value to achieving desired business-critical outcomes.

Procurement considerations

The following features all require consideration in the lead up to a procurement process and continuous assessment during the process. Client organisations will need to prioritise and balance these according to their particular business-critical outcomes, organisational structure, capability, competence, regulation and budgetary restrictions.

Achieving project quality

- Should not be assumed nor taken for granted as a consequence of selecting a particular procurement route, and the client

- must emphasise and define the quality levels required throughout the process.

- Takes account of appropriate compromises needed to be made between time and cost in the full knowledge of any consequential impact on quality to be delivered.

- Requires provision to be made for innovation (virtually every building is a prototype) and how to allow differentiation between offers from potential contractors.

- Should take account of wider factors including whole-life considerations, choice of materials and products and recognising that the long-term operational cost for an asset is likely to far exceed the once-off capital cost of creating the asset.

Achieving cost certainty

- Depends on the probability of completing a project’s scope within the budget agreed between a client and contractor before the commencement of construction.

- Relies on a client organisation’s own cost benchmarking capability analysis and experience that might influence or undermine cost certainty.

- Is influenced by budgetary and/or regulatory or legal restrictions.

Achieving time targets

- Relies on the reliability of completing projects on time compared with that planned and

- Requires the identification of internal and external factors that could cause delay or disruption to the schedule, eg third party consents, product or service availability (scarcity), approvals and governance.

Dealing with technical complexity

- Depends on the client organisation’s prior experience in delivering a project of the type under consideration and the impact this has on:

- Risk allocation between it and the contractor (s).

- The shape of its delivery organisation.

- The clarity, precision and manner of specifying the client’s requirements.

Providing the flexibility to accommodate change

- Requires the client to have an understanding of the level of flexibility required to allow for changes in requirements at various work stages.

Understanding and managing project risk

- Requires clients to grasp the extent of uncertainty of funding, their organisation’s requirements and the nature of any constraints or dependencies in these areas.

- Needs clients to assess the amount of foreseeable changes and the definition of processes or allowances that should be aimed at securing best value during the procurement process.

- Needs an answer to the question of who is best able to own and/or manage the risks:

- Client.

- Contractor.

- Others?

- Needs clients to ask themselves whether they are able or willing to carry risks and

- Demands procedures for ownership, monitoring and mitigating risks aligned with any commercial principles.

Complying with statutory constraints and considerations

- Needs clients to be aware of the application of the regulations and, if so, what procurement procedure is best suited to the project? (See below).

- Requires clients to be aware of any specific planning requirements and constraints ie Section 106 Agreements, development consents, listed building consents, or similar conditions and restrictions on development.

Procurement timing depends on client capability

- Identifies the pre-contract organisation including all procurement, legal and subject matter experts, senior management stakeholders, approval and corporate governance processes.

- Achieves an early identification of the post-contract organisation and devising appropriate interventions to improve, enhance or augment capability.

- Liaise and manage the handover between the pre-contract and post-contract teams during the transition to the post-tender phase of the project.

What is best practice in procurement?

When procuring projects, there are certain principles that combine to underpin best practice and these are broadly transferable across all projects. Given the range of considerations associated with the procurement of projects, best practice has many facets and broadly seeks to satisfy the following:

- Takes account of the design and execution of a procurement strategy based on the client’s capability and the project’s complexity.

- Enables the contractor and its supply chain to take a margin reflecting prevailing market conditions.

- Delivers the requirements of external stakeholders whether these are regulatory, community-related or others, eg funders.

- Ultimately delivers specified business-critical outcomes.

What does best practice look like?

The management systems that underpin examples of procurement best practice include:

Structured procurement processes

- Providing a clearly defined, unbiased process for the selection of suppliers (including transparent evaluation systems and criteria) that determines the ability of suppliers to meet the specified requirements5 and add value.

Quality-based selection processes

- These can enable the identification of potential suppliers with relevant experience, and selection of the most appropriate firm on a qualitative basis, thoroughly discussing the project details with the best-qualified firm.

- When applied to larger projects, suppliers should be pre-qualified based on (in part) their implementation of best practice, where responsibilities are written into tender and contract documents.

- Offer non-adversarial selection methods that do not force costs down compromising resources such as staff and materials.

- Means that the most important quality-based attributes by which a supplier’s suitability to carry out a particular project can be judged regardless of the selection process are:

- Technical competence (including safety).

- Managerial ability.

- Availability of resources.

- Corporate integrity.

Achieving best value

- Is achieved by choosing the right type and level of competition.

- Is gained by adopting processes where the design and construction teams can and should work together as an integrated team.

- Means taking a ‘whole-life’ approach to specifying and costing the project.

- By regarding value chain evaluation as a multi-value system where each of the stakeholders evaluates value from its particular perspective.

Why use best practice procurement procedures?

The main benefit derived from best practice procurement procedures is improved returns from increased asset value and reduced whole-of-life costs when measured in both monetary and non-monetary terms. This may be achieved through:

- Reducing costs associated with maintenance, building re-fitting and safety risks over the economic life of the asset.

- Improving design quality and innovation as pressure to minimise costs is replaced with positive incentives to achieve best practice.

- Increasing market sustainability as the pressure on suppliers/providers to simply cut costs is reduced and they are encouraged to innovate and seek better design solutions.

- Improving risk management by allocating risk ownership appropriately to those most able to influence or control them.

- Making a positive impact on the community, the environment and other external stakeholders.

- Reducing the likelihood and number of contract disputes.

Poorly defined requirements or mechanisms (not necessary understood by all the key parties to the contract) and errors or omissions from the contract documents all feature in the top five causes of EC Harris’ latest global construction disputes report in Table 4.1 below:

All of the above revolve around a mistake or failure which makes them all to some extent avoidable. In the UK, more recently, EC Harris reports that it has become more prevalent for disputes to occur due to all parties failing to understand their contractual obligations, which has been linked to the ambiguous and sometimes overly legalistic drafting of bespoke contracts. Therefore, if client organisations adopted more standard forms with fewer amendments, the occurrence of this type of problem could be reduced.

Recent developments – collaboration in construction

- HM Treasury – UK Charter 2011, establishes the high-level objectives and behavioural changes needed to reduce the costs of infrastructure delivery. These objectives are set out in the commitments made in the Government’s Plan for Growth at Budget 2011, the Infrastructure Cost Review: Implementation Plan (March 2011) and are consistent with the Government Construction Strategy (2011).

- BS11000 – Collaborative Business Relationships

- Businesses in the construction industry have come to recognise that promoting collaboration and achieving less adversarial working relationships between clients and contractors helps attain business-critical outcomes.

- In 2010, BS 11000 was published in two parts:

- Part 1: A framework specification, defining the standard against which organisations can be assessed and certification gained.

- Part 2: Guide to implementing BS 11000–1 is a guidance document to support organisations seeking to implement a framework specification structured in terms of ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’.

The overall aim of BS 11000 is to help organisations establish collaborative working that can result in increased efficiency and transparency, leading to better cost and risk management, as well as levels of innovation not normally achieved in typical client-supplier relationships.

- UK Infrastructure Route map 2014

- Establishes a tool kit in which the principal components:

- Enable the adoption of the common characteristics and behaviours associated with successful infrastructure project and programme delivery, including:

- - Early visibility and commitment to the pipeline of programme opportunities or the specific project.

- - Clearly articulated sponsor requirements adopting whole life principles linked to service outcomes that define the project or programme requirement.

- - Effective governance, accountability and timely decision-making.

- - Early supplier engagement that involves all tiers of the supply chain.

- - Effective use and structuring of standard contracts such as the NEC suite to align risk, reward and behaviours in an integrated supply chain.

- - Appropriate incentive approaches that stimulate further integration of the supply chain.

- - An environment that encourages innovation and departures from standards that embed cost and add no value to the outcome or safety.

- Enable the adoption of the common characteristics and behaviours associated with successful infrastructure project and programme delivery, including:

- Provides a suite of assessment tools to enable sponsors, clients and the supply chain to align behaviours and identify capability gaps.

- Describes pragmatic approaches to compliance with EU procurement legislation.

- Offers an ongoing role for industry leaders and experts in the infrastructure sector to identify, develop and disseminate best practice.

- Establishes a tool kit in which the principal components:

- Alliance Agreements

Alliancing is a relationship between two or more parties which have aligned commercial interests and aim to work together to deliver a project in a collaborative and constructive way. An alliance agreement is no more than a consensual commitment between parties to work towards a common objective in a collaborative way. Such agreements have no contractual effect and are usually referred to as ‘charters’.

Competitive selection procedures

When selecting an appropriate competition procedure it is crucial to know whether the client organisation is designated as being either public or private sector. For some projects that relate to public services it is also necessary to understand the structure of the client organisation and whether specific control and functional tests, first established by the Teckal6 case, impact on this designation. A public sector body must comply (with certain exceptions) with the EU regulations which ensure that public sector bodies award contracts for projects that are above the specified value thresholds only after fair competition and only on the basis of the lowest price or the most economically advantageous offer.

When a contract does not fall into any of the exemptions provided for in the regulations, it is then necessary to establish which category it falls under. The covered categories as identified in the regulations are works, services and supplies. The regulations will apply in full to these various categories. However some services (Part B services) are covered by a special, less regulated regime.

A public sector body is free to choose a competitive selection procedure for projects that are under specified value thresholds for works, services and goods. When specified value thresholds are breached, a public sector body must adhere to the stipulated competitive selection procedures contained in the EU Regulations that vary between open, restricted, competitive dialogue and negotiated procedures.

Private sector client organisations are not bound at all by the regulations. However, BS EN ISO 10845: Construction procurement ISO 10845 does set out the steps and documentation entailed in a fair and competent tendering process. The underlying principles require the process to be:

- Fair: impartial and providing simultaneous and timely information, not prejudicing the interests of the parties.

- Equitable: non-award to a compliant bidder only if there are restrictions from doing business, incapability or incapacity, legality, conflicts of interest.

- Transparent: procurement processes and criteria for each project/programme to be publicised and verifiable, with decisions publicly available with reasons given.

- Competitive: system provides for appropriate competition to ensure cost-effective and best value outcomes.

- Cost-effective: processes standardised with flexibility to attain best value in respect of quality, timing and price.

Public sector procurement routes

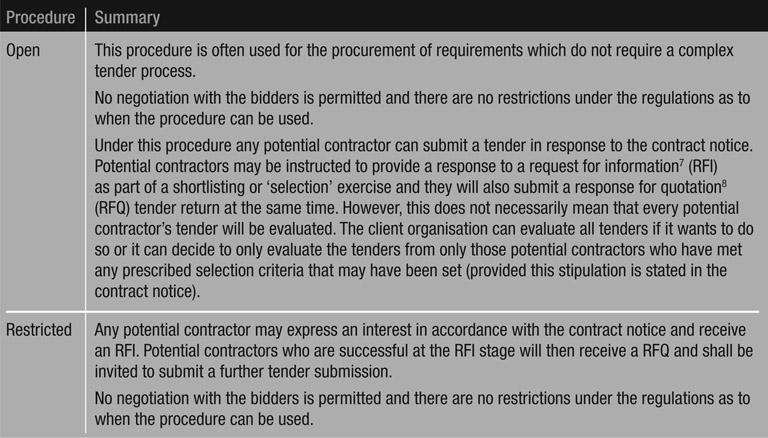

The following table (Table 4.2) summarises the four available competitive selection processes which are permitted for use in accordance with Directive 2004/18/EC (public sector). It is worth noting that Competitive Dialogue is not permitted where Directive 2004/17/EC (utilities) applies.

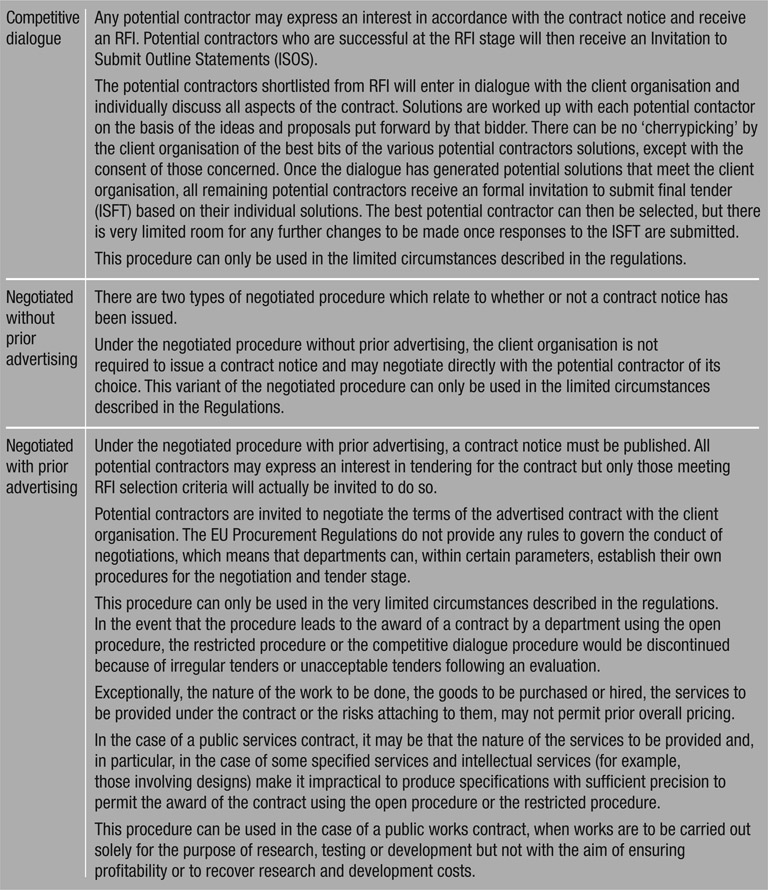

▯ Figure 4.1: The competitive selection process

The application of the competitive selection processes is illustrated in Figure 4.1 above.

How should clients get appropriate advice?

Procuring projects can be a complex process that requires the seamless bringing together of differing variables that were listed earlier in this chapter.

Whilst the reflex response to the challenges presented by a given project may be to consult a suitably qualified lawyer, there are a number of more important considerations including:

- Strategic project advice from an RIBA Accredited Client Adviser.

- Professionally produced designs and specifications from the right architect for the job.

- An accurate cost estimate from a cost consultant.

- Selecting the right contractor.

- The services of a project manager.

What are the basic features of each contract delivery method?

The characteristics of the delivery contract need to integrate with those procurement considerations that are defined at the start of this chapter, which are those of cost certainty, risk transfer, the need to accommodate change and the required level of quality.

A summary of contract delivery methods is below.

Turnkey or GMP

- Also known as ‘GMP’ (guaranteed maximum price).

- Usually based on bespoke terms (only one standard form – FIDIC Silver Book).

- Contractor takes most of the risk.

- Contractor usually deals directly with the employer.

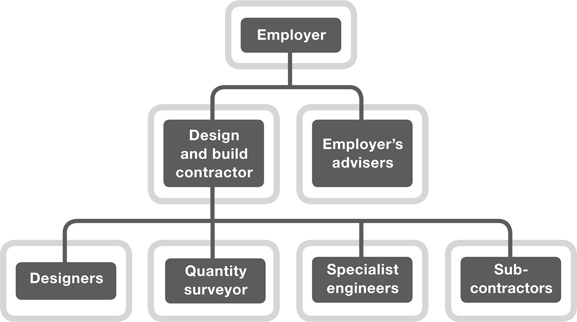

See Figure 4.2 on facing page.

▯ Figure 4.2: Organogram for Turnkey or GMP procurement

D&C (Design and Construct)

- Can either be single Stage Two stage or Develop and Construct (hybrid two stage).

- In single stage the contractor provides

- a fully detailed offer based on comprehensive employer’s requirements,

- For Two Stage the contractor is selected via an initial tender based on preliminary costs and programme, based on outline employer’s requirements.

- Contractor takes specified risks.

See Figure 4.3, below.

▯ Figure 4.3:

Organogram for Design and Construct procurement

Develop and Construct

- Mechanism

- Design team initially appointed by the employer, in contemplation that it will be novated to the contractor after RIBA Stage C or D.

- The employer separately appoints project manager, employer’s agent, cost manager and CDM coordinator.

- The design is completed to Stage C or D; meanwhile the contractor is selected and appointed on a pre-contract services basis.

- The contractor’s initial appointment is typically made on a qualitative assessment (with or without the cost of preliminaries, overhead and profit for the works to be comprised in the Building Contract).

- The design team is usually (but not always) novated to the contractor upon its appointment.

- The contractor works with the design team and employer to develop the scheme in accordance with the brief and budget.

- Downstream procurement strategy is developed jointly by the contractor, employer and employer’s advisers.

- The contractor may elect (or may be required) to involve key subcontractors in the design development and tendering processes.

- Advantages

- Effective management underpinning a fair allocation of design, performance and construction risk.

- Early validation of strategic programme and construction logistics.

- Full integration of design and construction through collaborative working.

- Overlapping of design and procurement without risk of unpriced design development.

- Reduced need for an additional shadow design team, where the original team is novated.

- Progressive coordination of the work of specialist contractors.

- Risk of information release lies with the contractor.

- Option for contractor to engage employer’s architect and engineers directly.

- Risk of design detailing rests with the contractor.

- High scope for value engineering.

- Low employer risk to cost and programme overruns.

- Single point responsibilities with contractor.

- Shorter tender documentation period.

- Capable of conversion to guaranteed maximum price.

- Contractor buy-in to cost and programme.

- Early contractor input on programme, construction methodology and content of subcontract packages.

▯ Figure 4.4: Organogram for Fixed Price procurement

- Disadvantages

- May attract cost premium for post-contract design development and risk.

- Quality needs to be carefully defined and supervised.

- Post-contract changes unlikely to be uneconomic.

- More difficult for employer to control choice of subcontractors.

Traditional fixed price

- The traditional form of contract is based on a fixed price (lump sum) derived from full drawings, a detailed specification and either bills of quantities or an activity schedule.

- The work is subject to re-measurement if the scope varies.

See Figure 4.4, above.

- Mechanism

- Competitive tenders are based on complete design drawings for all elements.

- Measured bills of quantities or, alternatively, activity schedules are part of the tender documentation package.

- Detailed preliminaries are provided.

- Some elements may be the subject of Contractor Design Portion Supplements (CDPS) within the contract for specialist products and services for example cladding.

- Advantages

- Greater cost certainty provided; total cost known at outset of contract (providing scope remains unchanged).

- Better cost control of variations.

- Programme certainty – time frame established at outset of contract.

- Design responsibility remains with client.

-

Disadvantages

- Relies on full design information prior to tender.

- Longer overall pre-commencement period required to develop complete design prior to seeking competitive tenders.

- Full design not usually achievable; leading to some Contractor Design Portion Supplements.

- Client is penalised if major changes introduced during contract.

- Cost risks remain with the client.

Target cost (may be used for traditional or D&B)

-

Mechanism

- A target cost for carrying out the works is agreed between the employer and contractor.

- The contractor is paid the actual cost incurred (less some disallowed costs) up to the agreed target cost.

- If the final cost of the works is less than the target cost, the contractor and employer each benefit from receiving a pre-agreed percentage of the shortfall.

- If the final cost of the works exceeds the target cost, the contractor is liable for a pre-agreed percentage of the overspend.

Managed/management contracting

-

Mechanism

- Design team appointed and retained by the employer throughout the project.

- Shortlisted contractors are invited to bid on the basis of their fees, method statements and preliminaries based on available information and the requirements of the strategic programme.

- Bidding contractors are interviewed formally following the submission of their bids

- to discover their corporate and personal credentials, to ensure that the successful bidder will fit well with the employer’s team.

- A management agreement usually (but not always) consists of two parts: pre-construction and construction.

- The management contractor subcontracts construction works as a series of works contract ‘packages’.

-

Advantages

- Rapid method of procuring a contractor.

- Enables an early start on-site.

- Early validation of strategic programme and construction logistics.

- Facilitates ‘fast-track’ construction.

- Well-suited to large complex projects.

- Flexibility – design can extend into the construction period.

- Flexibility – later procurement of finishes to suit the design programme.

- Easier incorporation of changes into the contract.

▯ Figure 4.5: Organogram for Management Contracting procurement

- Early contractor input on programme, buildability and the contents of subcontracted packages.

- Programme and cost plan agreed with the design team before the work starts.

- Engages the employer in rolling decision-making throughout the construction period.

- The content of works contract packages can be precisely detailed prior to procurement.

- In practice, subcontractors take more ownership of programme and quality issues.

- Useful employer participation in the choice of subcontractors.

-

Disadvantages

- Minimal risk for the contractor.

- Close attention is required to optimise the interfaces between the subcontracted packages.

- The subcontract strategy may not always align with the design method.

See Figure 4.5, above.

▯ Figure 4.6: Organogram for Construction Management procurement

Managed/construction management

-

Mechanism

- Procurement of construction manager as for management contractor.

- Work packages are arranged by the construction manager as discrete trade contracts between the employer and trade contractors.

-

Advantages

- Rapid method of procurement.

- Enables an early start on-site.

- Flexibility – design can extend into the construction period.

- Flexibility – later procurement of finishes to suit the design programme.

- Easy incorporation of changes into contracts.

- Benefits from the early input (from the construction manager) on programme, buildability and the contents of trade contract packages.

- Programmes and cost plans are agreed with the design team, including information release dates before the work starts.

- Trade contract content can be precisely detailed prior to procurement to minimise works which fall between packages.

- In practice, trade contractors take greater responsibility for programme and quality issues.

- Creates the ethos of the ‘single commercial team’.

- Provides greater employer input into the choice of trade contractors, which requires a higher level of employer involvement in making decisions throughout the programme.

- A direct relationship between the employer and the trade contractors may be attractive to the latter and can lead to their improved performance.

- The employer retains the ability to influence the direction of the project.

- Disadvantages

- The construction act places the employer at risk of direct adjudication from trade contractors.

▯ Figure 4.7: Organogram for an alliance model for construction procurement

- There is a greater administrative burden to the employer who has to deal with numerous trade contract documents.

- Requires careful definition and scoping of roles and responsibilities.

- There is no construction manager buy-in to cost and programme – project delivery risk lies mainly with the employer.

- Approximately 15% of project costs are cost-fixed when the employer enters into the first trade contract.

- Close cost control and detailed reporting is required.

- Close control of procurement and construction programmes is required.

- There is a risk to the programme, enduring well into the construction phase as the scope of work develops.

- The employer is exposed to greater contractual risks.

See Figure 4.6, on facing page.

Alliance

There are a number of alliance models in current use, particularly within the infrastructure sector. Alliance models can differ in structure but the fundamental principles (as discussed above) are common to all.

- Mechanism (for the model shown in the diagram above):

- Operates as a series of separable bilateral agreements between the employer and each member.

- Alliance members are both individual contractors and professionals.

- Bilateral (commercial) agreements

- are based on a target cost contract mechanism (see above), where benefits and liabilities are transferred into and out of a central sinking fund held by the employer.

- A multilateral alliance agreement binds the members together.

- Each member benefits from a pre-agreed percentage of the sinking fund.

See Figure 4.7, above.

PPP (public/private partnerships)

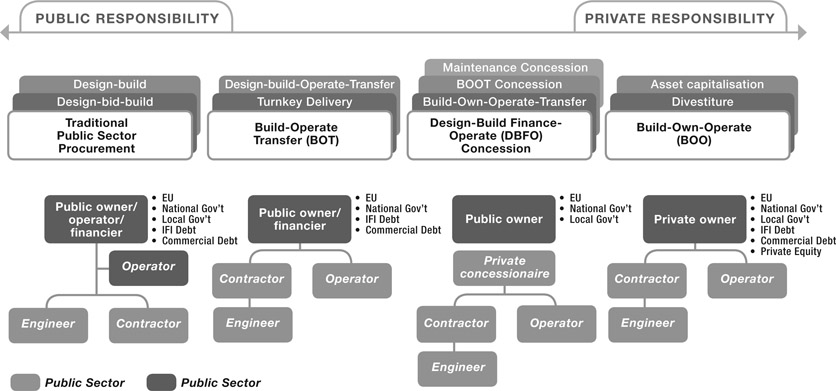

- PPPs can cover all types of collaboration between the public and private sectors to deliver policies, services and infrastructure.

- PPPs are arrangements typified by joint working between the public and private sectors.

- Where the delivery of public services involves private sector investment in infrastructure, the most common form of PPP is the private finance initiative (PFI).

- The perceived advantages of PPP include value for money, better risk allocation and reduction in whole life costs, while providing better incentives to perform.

- However, the downside is loss of public sector control by the public sector over budget, privatisation of public services and greater cost in the long term.

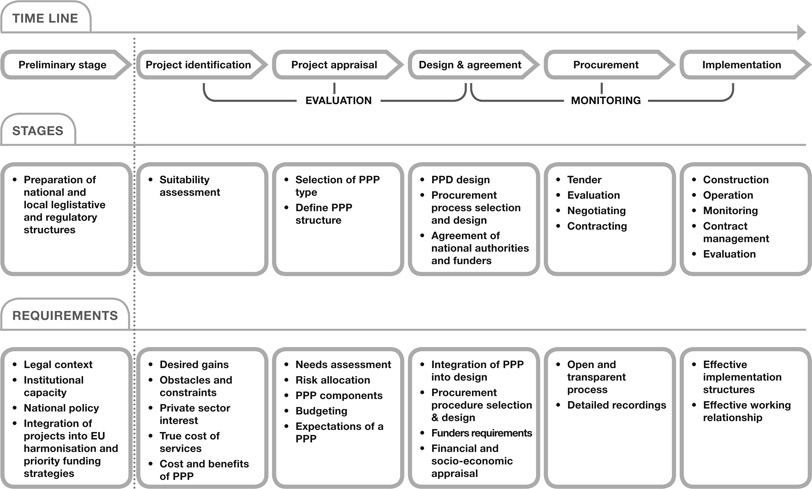

- Figures 4.8 and 4.9, on the facing page, summarise PPP possibilities and processes.

▯ Figure 4.8: Public/private partnerships – allocation of responsibilities by type of arrangement

▯ Figure 4.9:

Public/private partnerships – work stages and requirements

Construction procurement best practice

Gareth Hird in conversation with Peter Ullathorne

What are the main considerations in getting best procurement in the construction industry?

I think these can be summed up in the simple stages of:

- Have early conversations with all parties.

- Define the brief.

- Be realistic.

- Understand and take into account prevailing market conditions.

- Engage with constructors at an early stage in the design process.

- Appreciate everyone has the right to make a reasonable profit.

- Understand the relationship between time, cost and quality.

If you’re doing all of those properly, you will be on course to succeed and should avoid the pitfalls which see poorly constructed projects delivered, or those that are late or over budget, or both.

Talking early on with potential suppliers is useful too, rather than just springing a procurement exercise on them without warning. You may find some of the key construction firms who would be most suitable for a project are busy working on a pipeline of work that stretches several years ahead. If you come to them at the last minute, they may be unwilling at that stage to embark on four to six weeks of lengthy pricing work in order to submit a tender. Whereas if they had advance knowledge of this work and its associated tendering, they could assess if this was a project they would be suitable for and keen on, allowing them to plan the resources for the subsequent tender process a few months hence.

How about defining the brief? How does that work?

Clients need to rely on the most appropriate professional advisers to engage with them at the earliest stage of brief-writing. Typically RIBA Accredited Client Advisers would be used in this role. They will investigate and question the clients to discover their detailed accommodation requirements related to achieving their missions and purposes. They will advise the client in his choice of architects and other consultants as to who can best realise the brief in physical terms.

Perspective

by Gareth Hird

What’s your attitude towards profit?

Clients may make the mistake of trying too hard to drive down professional and contractor costs. Once clients accept the necessity of a reasonable profit for all project participants, they will not end up trying to screw down the costs. Driving down costs as the number one priority can create pressure that is passed down the supply chain via subcontractors which results in more intangible and unforeseen risks being introduced, and contributes to a dilution in quality. Taking the approach of ‘reasonable profit’ from the outset will mean that the correct costs of a project should be clear to everyone involved.

Why is it so important to understand and take into account prevailing market conditions?

The construction industry is influenced by outside market forces and effective clients should be aware (through the advice of their professionals which should include a RIBA Accredited (Client Adviser) of how these conditions will affect the availability and prices of particular contractors, the cost of materials and specialist services. The state of the general economy at any particular point in time may be different to that prevailing within the construction industry. Given good advice, effective clients are able to predict the impact of, for example, a market recovery that will restore construction companies to ‘busy’ status and increase the cost of their tenders and materials. Conducting a sound tender exercise and securing the best possible contractor appointment is not something that should be left to chance. Effective clients should do all they can to avoid being at the mercy of the market or whoever decides to walk through your door looking for work. It may be a cliché, but construction procurement really is ‘horses for courses’, so clients need to make sure that only organisations of the appropriate size and experience compete in a tender process.

How does the public sector fare in this sector?

Often just getting onto a framework can be a major challenge. The existing procurement process means that big-name firms frequently get onto frameworks because they have the resources to engage in lengthy and costly tender and framework exercises. However, visibility of their layers of suppliers and subcontractors may not always be clear, and each sub-layer will have an associated cost, including a fee for administering the framework.