Introduction

This chapter refers to a project as though it is actually on-site. This is the busy, exciting period; or even busier and even more exciting than before – if that is possible. There will be lots of activity, by lots of people, on- and off-site, spending lots of money every week and no going back. What does a client do now? Despite all the busyness, the official answer is probably ‘not a lot’ except pay the bills and make the relatively minor decisions on issues such as paint colours. So do not make changes, enjoy the experience, be enthusiastic and appreciative, and wait patiently for your completed building and project to be delivered. This is when everything should come together – in a physical form – so some pre-site as well as on-site issues are incorporated in this chapter.

The project on-site – changing responsibilities

As the project moves onto site, so the site responsibilities change over. This can be an unexpected shock for some clients. They still own the real estate but responsibilities move over to the principal contractor – for security, access, insurance, fire precautions, and the safety of workers, visitors and the public – as well as for executing the works.

Clients, their staff, advisers and their own direct contractors need to understand and respect these temporary arrangements. They may need specific briefings and instructions – by the contractor. It may also be appropriate to have some joint walk arounds, briefings and handovers with the client – during the mobilisation period between placing the primary order as the contractor takes possession. If the client does not feel sufficiently confident or knowledgeable about their own buildings or site, they can ask the confident and knowledgeable design team and property advisers to undertake the role. If a design and build approach or managed form of contract has been adopted, then a pre-construction period with greater involvement of the contractor may have occurred with greater opportunities for buildings and site familiarity.

Going to site

Having relinquished responsibilities for the site for the duration of the works, it is important that the client understands the protocols of going to and visiting the site.

Here are some tips for clients:

- Make an appointment or receive an invitation – do not go unannounced, it is discourteous.

- Go for a purpose, identify the purpose, achieve the purpose. Have more than one purpose, have a list, do what is on the list, check what is on the list.

- Be prepared to be inducted on your first attendance on-site. Allow time, pay attention and set a good example even if you have been on construction sites before.

- Sometimes it is possible to go to the site without going on-site, for example to attend a meeting in site accommodation or nearby without the necessity of setting foot on site; do not go for one near-site purpose and then adopt another on-site activity.

- Become familiar and comfortable with personal protection equipment (PPE) of footwear, jackets, helmets, protective eyewear and gloves to suit the situation. If site visits are to be a regular activity, think of getting your own PPE with your own logo (and not someone else’s), which you keep or leave stored securely on-site.

- Always tell people where you are going and when you should be back.

- Always sign in and sign out.

- Always take advice and directions when on site.

- Be observant on-site for your own safety and of others. Most accidents happen through lack of familiarity; and a feature of construction sites is that they are constantly changing.

- Always set a good example in all such matters – after all you are the client! Overfamiliarity can lead to complacency and increased danger. This is, of course, an extreme example.

Meetings on-site

Meeting arrangements are different when the project is on-site and construction is underway, in frequency (more often), in regularity (some more regular plus others more spontaneous or individual), in attendees (more participants and from different sources). More people and organisations arriving and being involved seem to mean more meetings!

The client will need to carefully consider which meetings to attend or at which to be represented or not. It is good to resolve such matters from the start – and yet be flexible enough to optimise commitments, contributions, information and presence.

If the client is a stranger to site meetings, it is wise to take it steady – especially initially – as an interested observer or attendee. Sit next to someone who can be a guide or buddy; leave any items or concerns until ‘any other business’; be prepared for a certain amount of banter between parties. Decide what to do about jargon – whether to ask for clarification sooner or later. Expect differences – refreshments may be tea and bacon rolls rather than coffee and biscuits or croissants (or possibly vice versa).

Project managers or managers of projects

There are some subtle differences between being involved as a project manager and contributing to the management of the project. Client project personnel make a difference. These are the people who work together to push the project along; collectively and individually they have an accurate view of the project overall and its prognosis for satisfactory delivery. They anticipate problems, and if they cannot avoid them, they try to solve them. They understand blame but that is not their first reaction. They may be seen or heard conversing before or after meetings, in corridors and car parks, talking about the project (not everything is resolved in formal meetings or by emails). This group exists on most projects; some are much better and effective than others. Clients need to be aware of such groups and decide how to engage with them individually and possibly collectively – and how to participate. Generally these people operate at project level and so they are suitably project knowledgeable – not too senior, confident, not too junior. The good participants are those with whom the client would like to work with again. This is not a ‘steering group’, it is a collection of ‘drivers’. Sometimes it is all subconscious. It is a form of selective, project-focused collaboration.

Value engineering and value sourcing

Value engineering attempts to achieve additional value for the same or little additional cost; or attempts to achieve the same value for less cost, usually achieved through scrutinising functionality, technical specifications and quantities (as units, volumes and areas). The ultimate target might be to achieve greater value and also reduce costs – sometimes summarised as ‘even more for even less’.

Value sourcing is different and is all about trying to obtain the same value at a lower cost by seeking alternative sourcing of goods, products and services or by contract arrangements – which may also lead to different technical solutions.

Value engineering might be summarised as ‘make it cheaper’, while Value Sourcing might be ‘buy it cheaper’.

When the team is undertaking value engineering and sourcing in order to achieve budget reductions, expect the need to identify savings equivalent to twice the gap because only half will usually be deliverable. Therefore go for big dramatic effective possible savings rather than many small possibilities. Also identify, tackle and engage with the ‘quiet’ participants in such exercises. They, too, can contribute.

Change – good and bad

Capital construction projects are all about change. That is good. Projects take a situation or status quo, manipulate it – usually over a relatively short period – and then deliver an improved status quo for the benefit of the customers, users, society, civilisation, etc. over a long period.

The construction project by itself does not usually provide all the changes required. People, equipment, technology and new ways of working will also be necessary. A physical hospital building contributes to a health facility, a school building is part of an education establishment, a house becomes a home, and so on.

And yet there is great sensitivity and concern about ‘change’ taking place within and during projects. Within the individual stages of projects good ideas, development and refinement are encouraged to suit the stage of work. This is sometimes called iteration. The difficulties occur when changes are identified or requested that are out of sequence. They are being requested at an inappropriate stage – usually too late – with the consequence that such potential changes can be disruptive to the timetable, the budgets and the holistic solution if adopted, and even if considered but not adopted. Here are some observations about dealing with change on projects:

- Have a change management system or protocol for processing the assessment and decision-making of potential changes.

- Also have a change resistance mentality, which stops topics getting into the change management system.

- Differentiate between ‘nice to have’ and ‘must have’, and then apply common sense.

- Changes can result in savings (sometimes) as well as extras (more often).

- Establish if the change alters the signed-off brief, the signed-off designs, the signed contract, the works themselves or some other aspect. It is surprising how many changes have their origins earlier in the previous project processes – going right back to within the initial brief or feasibility studies or budget or scope assumptions.

- Make financial provision for possible changes (a good idea, usually as a contingency sums) within the contract sum and/or within the overall project budget.

- Categorise all changes, perhaps on the basis of client changes, design development, procurement influences, regulation and statutory requirements, site conditions and other combinations.

- It is possible to include some simple credits that can be used to pay for extras, for example with higher specifications or functional provisions or provisional sums, or day work provisions.

- When a change is identified there can be agreed review routes on the lines of:

- A full comprehensive report with implications, alternatives and recommendations, about ten working days to produce, costing say £5,000 to £10,000 to produce if paid for or not, and disruptive to on-going activities in its production even if not implemented.

- A simple short assessment, taking about five working days to produce, at a cost of say £1,000 to £2,000, with less disruption to activities.

- A 15 to 20 minute discussion within the team members present at the time with the originator of the request. This process can often squash a changed idea or considerably refine it to enable one of the other approaches to be adopted effectively. Additionally, this may stimulate requests to be thought over before being expressed – since they are going to be openly and positively cross-examined.

- Maintain a schedule of change assessments and monitor the number, status and decision-making – managing accordingly.

- Undertake ‘lessons learned’ exercises at the end of the project against the whole change schedule to assist in improving the accuracy of predictions and efficiency of processing.

- Expect some ‘extras’ to be twice the expected cost and some ‘savings’ to be half the expected saving initially – interrogate and negotiate accordingly.

- Expect people to be ‘helpful’ in raising a change topic by providing the answer rather than the question, eg they will request, ‘We need to widen the door opening. How much will it cost?’ without saying why. Fundamentally, the client asks questions and the project team provides options and answers. The same should apply to change items.

- Expect some ‘new’ ideas to not appreciate that they may be covered by existing provisions and/or have particular justifications – sometimes good memories, project commitment and a steady nerve can be of assistance.

Construction programmes and project programmes

Usually when the project is on-site the predominant programme will be a detailed construction programme prepared by the principal contractor covering the contracted works within the contracted start and finish dates. This can be a very useful document usually represented as a bar chart, preferably with a method statement that is a commentary on how the project is to be constructed.

However, usually not everything that needs to be done on the project – and that is of interest to the client – is certain to be reflected in the construction or works programme. These omissions are to be expected and need to be identified, tackled and monitored by the client and their advisers – because they may be their responsibilities – and be vital to the project overall. These further topics may include:

- Off-site works and fabrications with inspections – frequently construction programmes only cover the on-site works.

- Placement of orders to and works by utility suppliers.

- Orders and installation of client-supply furniture, fittings and equipment (FF&E), which may overlap with or immediately follow the construction works.

- Celebratory events such as initial start-up, turf cutting, weather tightness, topping out, first phase completion, overall handover, occupation and official opening.

- Release of provisional sums, clearance of remaining design topics, resolution of samples/mock-ups/first rooms.

The selection of off-site sourcing of raw materials, processed materials components, sub-assemblies and whole units will affect the on-site timescales and costs of capital works but also impact on the running costs thereafter.

Observing the works in progress

To begin with, work can seem to be going backwards. More material may seem to leave site than arrive on-site – such as demolition arisings and excavated material. Existing buildings can be demolished or stripped out. With basic foundations and certainly with new basements, the project may be seen to be going downwards rather than upwards. So in due course it can be a key point on the programme when the project ‘comes out of the ground’.

Construction sites are busy places, usually with multiple activities taking place at the same time. It can be difficult for clients to monitor the progress and assess if the project is going to be on time for completion.

The specialists in such matters can provide reports with assessments of progress against programme or timeline. Different approaches can be adopted including:

- Critical path monitoring, remembering that there can be many near-critical activities.

- Activity counts – as in how many activities completed per week/month against as planned.

- Milestone achievements.

- Activity starts – for trades. Trade starts are easier to identify than trade completions.

- Financial valuations and payments against predicted cash flow.

Clients should consider standing still in the same places on-site every time they visit and look at the view. This way they will be able to see progress. Take a photograph or two – even a selfie with the project in the background. Your clothing and expression will indicate the time of year, the weather conditions and your opinion on progress.

Quality

What is quality? Is ‘quality’ the best word to use? Is it better to consider ‘performance’ of which quality is a part, along with scope, appearance, aesthetics, consistency, reliability, technical achievement, statutory compliance, tolerances, maintainability, robustness, removability and others? When there is a problem, disagreement, dispute or misunderstanding on quality, it is usually about one or more of these criteria. Which ones? Let’s get the right ones on the table.

Pre-agreed standards and benchmarks sound like a good idea but they need time and effort to explore and agree. And they need to be pre-agreed – not as the problem arises and thus become part of the problem.

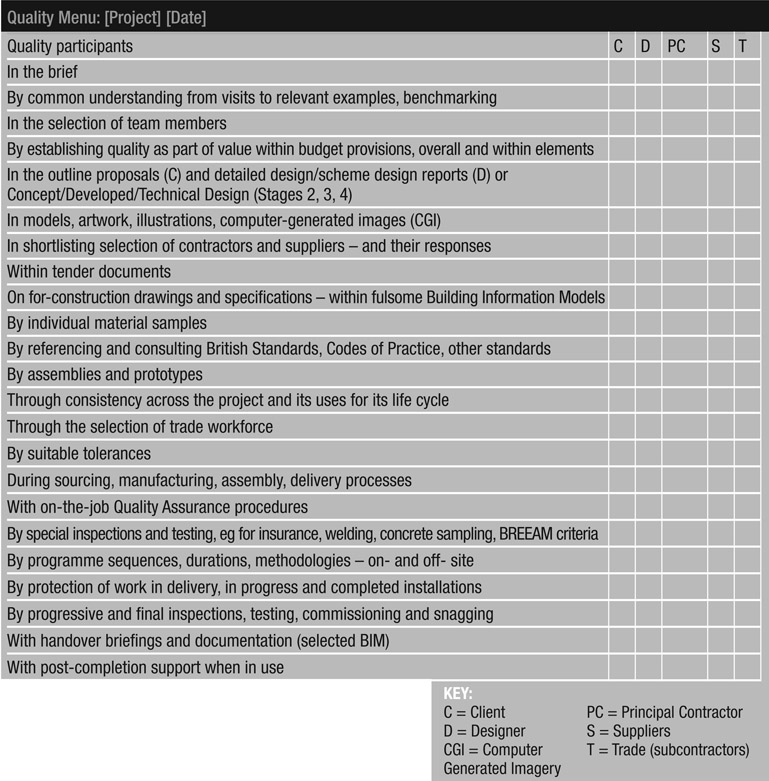

Table 9.1 (opposite) provides a menu of possible means of explaining the quality and performance expected or desired. In practice, the menu can be applied to establish who will produce the quality criteria or material and who will receive them, use them or rely on them. For example, the specification included in the contract documents is often thought to be a key means of conveying standards and requirements for workmanship and materials, however few see tradesmen consulting copies of the specification on-site. What are they using?

How to use the Quality Menu:

- Apply to specific projects. Add title, date and the current stage.

- Identify key parties for quality across the columns eg client, designers, principle contractors, suppliers, tradesman.

- Identify generic roles within the columns, eg originator (O), checker (C), user (U), tester (T), inspector (I).

- Work up the detail of topics, tasks and who does what.

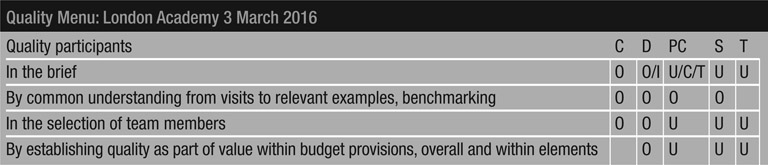

Table 9.2, above, provides a short example of how the table may be used.

When clients get into conversations about quality and performance – especially when the project is on-site – it is important that there are clearly established criteria and these are to hand, rather than a memory of the supposed criteria or assumptions or opinion alone. This attached listing or Quality Menu can assist.

Testing and commissioning

Frequently the primary representation for testing and commissioning is a period at the end of the contractor’s construction programme between the end of most of the works and the designated completion date.

This is an important period. It is not float in the timeline. It should not be allowed to be squeezed by late running works while still attempting to maintain the dates for completion/handover/occupation. An under-tested and under-commissioned project will almost certainly be regretted later.

Furthermore, the testing of materials, components and subsystems will usually have been taking place throughout the works period together with some commissioning of installations off- and on-site. Consequently, the testing, commissioning, plus likely inspecting and snagging are not just concentrated into the final testing and commissioning period. Clients need to agree with their teams when they or their representatives will need to be involved with or participate in testing and commissioning throughout the project period on-site. Soft Landings are also long landings.

What is a project execution plan?

A project execution plan (PEP) may be called by a number of other titles, which are all subtly different and in practice mean what the users choose them to mean, for example the project plan or the project management plan (PMP). Client’s requirements should be expressed in a brief, statement, wish list, Project Initiation Document (PID) or Business Case – in any document that explains and justifies what is required: the definition. Some say this is the project execution plan.

A good PEP will be a clever combination of the strategic, the specific and the tactical. It is as well to discover what the team means when it uses such terms. If there is a PEP, it is advisable to look at it regularly, make sure it is used and keep it up to date.

In conclusion

Every construction project in its circumstances is unique. Every development and resulting facility is unique. Every team of participants and stakeholders during the construction phase is unique in its composition and relationships. Most of these participants and stakeholders want the client’s dreams to come true rather than become nightmares. ◼

Characteristics of a good client

The need for architectural and associated design services frequently coincide with periods of fundamental change within the client environment, for example a major relocation or head office redevelopment. Such change can create a period of business uncertainty and staff instability. However, these kinds of risks of possible disruption are usually justified by the prospects of long-term benefits such as improved productivity and corporate positioning. One such example was the amalgamation of 5,000 Reuters London staff from seven disparate buildings into a new purpose-built office in Canary Wharf in 2006. This created a more productive atmosphere with closer linkages, up-to-the-minute technology based tools, plus a 30% reduction in office costs.

The overwhelming message from some 30 plus years of major change programmes is that beneficial outcomes can only be achieved if professional service providers – ie architects – and the clients are prepared to share the risks and challenges of a turbulent journey, as well as the intended benefits. In so doing, the soft factors that can mediate against successful programmes may be identified and dealt with by both parties in an equitable way. Clients need to accept that it is not possible to outsource all risks to a third party merely because the contract ‘says so’.

BP is a company that appears to encapsulate best practice here. One classic example of how a provider and client can work together to achieve remarkable outcomes occurred some years ago when BP Europe chose to bring all its office services together into a shared support centre. The project involved the amalgamation and centralisation of support services in 26 different countries – each of which had independent processes and skills employed locally to provide such services. The business goal was to halve support costs whilst improving staff perception of service quality (from an average of 3.4 to over 4.0 out of a total score of 5.0).

Initial efforts by the successful service operator and change partner (Fujitsu Services) met with growing hostility by many of the national BP affiliates as support services were extracted from the local environment and relocated to a shared centre in Holland. At the low point, the BP executive in charge informed Fujitsu that he was prepared to cancel the entire contract. However, sanity prevailed and the two companies sat down together to discuss how they could achieve a mutually beneficial outcome. Each accepted that blame needed to be apportioned to both sides. Neither should be prepared to resort to contractual wrangles. BP established a special task force to visit all

Perspective

by Roger Camrass

26 countries and begin a programme of staff education and orientation, geared towards promoting the benefits of a shared environment. Fujitsu relocated BP’s centre from Holland to Portugal to create an entirely new operation that had been purpose-designed for this demanding and multlingual European BP community. Within three years costs had been halved and customer satisfaction increased by 20% from the initial baseline. Everyone agreed that the programme had met its target, and the contract with Fujitsu was extended for several further years.

One of the most likely points of failure in such large scale and complex programmes is the contract itself. Many successful programmes have required both client and service provider to tear up the original contract and work on a more informal basis to achieve a successful collaboration.

This has been particularly the case in the public sector. For example, one of the UK’s largest government departments came within a hair’s breadth of launching a £10bn lawsuit against its primary IT vendor when a ten-year contract came unstuck. Poor initial contracting combined with overweight public scrutiny of ongoing services brought the two sides to a hostile stand-off. The situation proved so unsatisfactory that the entire IT sector was called to a meeting with the department heads. Any lawsuit would have endangered not just the prime contractor but a host of other engaged parties to the extent that the entire industry could have been crippled for years to come. The interesting outcome of this meeting was the creation of a joint task force to review not just IT but every aspect of the department, from property and energy consumption to staff productivity and automation. A report was prepared by five leading IT suppliers and submitted to the board. This invoked a full renegotiation of the existing ten-year, £10bn contract, as well as a strategic review of the business itself. As a consequence, the IT spend was reduced by some £350m per annum and the staffing of the department was cut from over 140,000 to less than 90,000 in just three years. One can only conclude that a dispassionate and fully collaborative approach will always yield far greater gains than a legal conflict.

In summary, the history of large change programmes and outsourcing contracts suggests that legal contracts alone can rarely – if ever – accommodate or stand up to the many changes in circumstance that large, complex organisations undergo. Instead, all parties need to find a mechanism for engaging in a ‘no-blame’ collaborative atmosphere where collective interests can be rewarded on a continuous basis, and an atmosphere of risk-reward is the primary driver. Many companies today describe this as a process of innovation and creativity that lends itself well to the new social and economic environment of the digital age.