3

COMPOSITION: PUTTING THE RIGHT PEOPLE ON THE TEAM

If the organization's context is supportive of teamwork, the next task is to determine the size of the team, who should be on the team, and how team members should be managed depending on their skillset and motivation. In this chapter, we will explore these issues and provide an assessment instrument for evaluating the composition of a team.

Team Composition and Performance

For a team to succeed, its members need two things: 1) the skills to accomplish goals laid out for the team, and 2) “fire in the belly,” that is, the motivation to succeed. In addition, research has shown that successful teams are comprised of team members who also have the following characteristics:1

- Effective interpersonal and communication skills

- A willingness to help and support other team members in their efforts to achieve team goals

- Good conflict management skills

- Ability to adapt to new situations

- Dependability and ability to take initiative to help the team achieve its goals

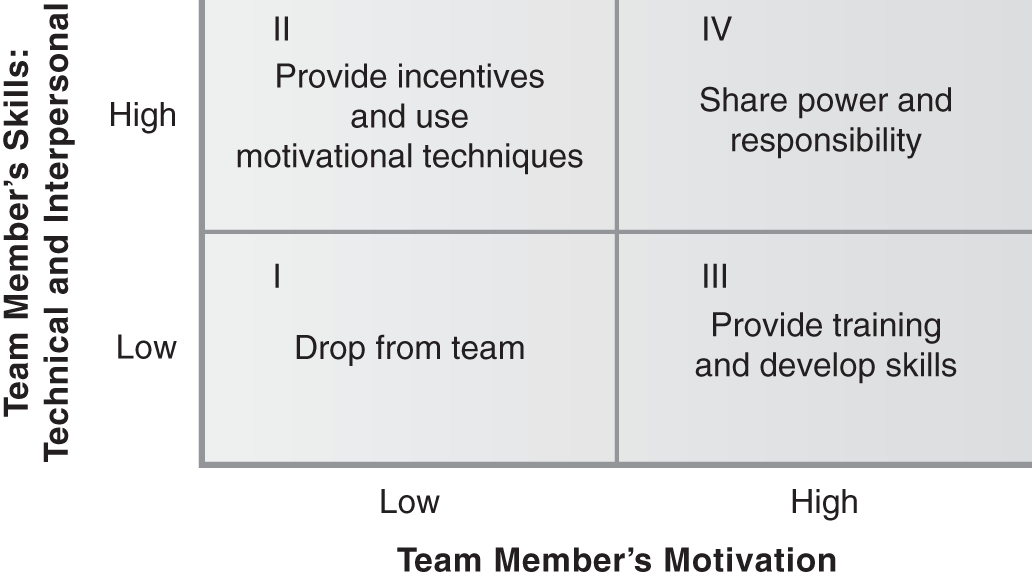

Effective team leaders understand that the way they manage the team and individual team members is strongly influenced by the degree to which team members are both skilled and motivated (see Figure 3.1). In some instances, team members may not have the necessary background and skills, or may not be properly motivated to work on the team, as seen in quadrant I of Figure 3.1. When team members are neither skilled nor motivated, team leaders may be wise to drop them from the team because the challenge of building their skills and motivating them is simply too daunting.

Figure 3.1 Team Composition: Evaluating and Managing Team Members Based on Skills and Motivation

When team members are skilled but not motivated (quadrant II), the team leader's role is largely a motivational one. We have found that empowering skilled team members with greater responsibility for team tasks and performance can be an effective way to increase a team member's commitment to the team and its goals. Naturally, it is preferable if team members are intrinsically rather than extrinsically motivated. In fact, when selecting someone for the team, it is important to determine to what extent the person has a passion and love for this kind of work, and to what extent she or he is committed to the team goals.

In contrast, when team members are in quadrant III, that is, motivated but not skilled, the leader's task is largely one of coaching and skill building. This requires that the leader play the roles of educator and coach. It also means that assessments of skill deficiencies are necessary so that an individual development and training program can be established to ensure that the person develops the skills necessary to be effective in completing the team's tasks.

The ideal team members are those from quadrant IV. These team members are both skilled and motivated. In this case, the wise team leader will share power and responsibility with team members, since they are capable of assisting the leader in developing team competencies and are motivated to achieve the team's goals.

As teams are formed, team leaders should meet with potential team members before selection to ascertain their ability to contribute to the accomplishment of the team's goals as well as their motivation to be part of the team. Offering a meaningful team goal or significant performance challenge generally can rally individuals to a team and motivate them. When team members believe they are being asked to contribute to something important—something that counts, that has vision—they are more likely to give their best effort than will people who are asked to serve on another team or committee that seems to serve little purpose (see sidebar: Setting a Lofty Vision to Attract Talent to Your Team).

Amazon.com is known for attracting and retaining some of the best and brightest technical talent around. It does this in part by maintaining one constant in its selection process: “Does this candidate have a strong desire to change the world?” Leaders are looking for people who want to achieve something important. In addition, job applicants are interviewed by teams of Amazon employees—in many cases, by the entire team that they will join. Team interviews often focus on finding new members who will bring diversity to the team (which is critical for innovation and is an explicit goal of the team interviews) and tests whether the recruits have the collaboration skills necessary to succeed in Amazon's team environment.

Team Size

There is no clear answer as to the size of an optimal team because size is determined in part by the nature of the task. Some managers like large teams because they believe that these teams generate more ideas and call attention to the importance of a project or functional area. Moreover, some managers think that putting people on a team is a good experience, and they don't want to leave anyone out. However, in general, small teams are preferable to large teams, and there are rules of thumb and certain pitfalls to avoid in determining team size.2

We find that large teams (typically over ten people) have lower productivity than smaller teams. Research reported by Katzenbach and Smith in their book The Wisdom of Teams suggests that “serious deterioration in the quality and productivity of team interactions sets in when there are more than 12 to 14 members of the team.”2 The greater the number of team members, the more difficult it is to achieve a common understanding and agreement about team goals and team processes. Large teams lead to less involvement on the part of team members and hence lower commitment and participation, which leads to lower levels of trust.

Although team size clearly should be determined by the nature of the task, much of the research suggests that the most productive teams have four to ten members. In summarizing research on team size, researcher Glenn Parker notes, “Although optimal size depends on the specific team mission, in general, the optimal team size is four to six members, with ten being the maximum for effectiveness. It is important to remember that many team tools in decision making, problem solving, and communicating were created to take advantage of small-group dynamics. Consensus, for example, just does not work as a decision-making method in a team of twenty members.”3

Amazon.com has experienced an explosion of growth throughout its short life and employs thousands of people. However, whenever possible, it deploys its workforce into “two-pizza” teams (the number of people who can be adequately fed by two pizzas) to promote team identity and foster commitment, accountability, and innovation within the team. Because two large pizzas typically feed six to ten people, you rarely find larger teams within Amazon. Thus, the rule of thumb is to choose the smallest number of people possible that will still allow the team to effectively accomplish its mission.

Personality Tests in Selecting Team Members

A number of companies today use personality tests as part of the selection process for employment and for assignment to teams. Personality tests that are often used include the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and the Personality Characteristics Inventory (PCI), but there are literally hundreds of such tests out on the market today.

Unfortunately, most of the research on the relationship between personality and job performance shows a very weak correlation. One study that reviewed the academic literature on the subject noted that correlations between personality and job performance typically fell in the .03 to .15 range—meaning that about 90 percent of the variance in job performance was not explained by personality factors.4 Context variables, the nature of the task, the individual's job skills and knowledge, and so on play a much larger role in a team member's performance.

While personality tests might prove to be useful with some teams in certain situations—tests deemed to be reliable and valid—we suggest that such tests be used as only a part of the picture when determining team composition. Team leaders should primarily look at the team members' skills, prior work experience, interest and motivation to work on the team, ability to work well with others, and so on as the criteria to be used when creating a team or adding new members to the team.

The Problem Team Member

One question we're often asked is: What do you do when one member of the team continually blocks the progress of the rest of the team? This person may always take a contrary point of view, vote against proposals everyone else supports, take a negative or pessimistic position on everything, and frequently miss meetings or not follow through on assignments.

The obvious question in response is: Why do you keep a person like that on the team? As we suggested earlier, team members without the requisite skills and motivation should be dropped from the team. However, sometimes the person has some needed competencies, or is a long-term employee, and terminating or transferring him or her can create additional problems as well. If a manager or supervisor is trying to build a team and one person won't buy into the process, some method of removing that person from the team or changing his or her assignment should be considered. Many executives, after feeling the need to cut someone from the team, express the sentiment that they wished they had done it sooner—or at least would have provided feedback and corrective action sooner.

The following kinds of actions have also been found to be successful in some (not all) cases.

- Direct confrontation between the team leader and the problem person. This may give the supervisor an opportunity to describe clearly the problem behaviors and the consequences if such behaviors do not change.

- Confrontation by the group. If only the team leader deals with the problem person, the conflict may be perceived by that person as just the personal bias of the leader. In a case like this, it would be better for the group to deal directly with the problem member collectively in a team meeting. The team members' feedback to the problem team member must be descriptive, not evaluative. They must describe the problem behavior and identify the negative consequences of the behaviors—all without punitive, negative evaluations of the individual personally.

- Special responsibility. It has been found for some difficult people that giving them a more important role in the team increases their commitment to the team process. The person might be asked to be the team recorder, the agenda builder, or the one to summarize the discussion of issues. One team even rotated the difficult member into the role of acting team leader with the responsibility for a limited time of getting team agreement on the issues at hand.

- Limited participation. One team asked the problem person to attend meetings, listen but not participate in the team activities, and then have a one-to-one session with the team leader. If the leader felt that the member had some legitimate issues to raise, the leader would present them to the group at the next meeting, but in all cases the decision of the team would be final.

- External assignment. At times it may be possible to give the problem person an assignment outside the activities of the rest of the team. The person may make a contribution to the work unit on an individual basis, whereas the bulk of the work that requires collaboration is handled by the rest of the team.

All of these suggestions can be useful when a person is a serious obstruction to the team. One must always be careful, however, to differentiate the real problem person from someone who sees things differently and whose different views or perspectives need to be listened to and considered with the possibility that this may enrich the productivity of the team. Teams can get too cohesive and isolate a person who is different.

Getting the Right People on the Team: How Bain & Company Does It

Getting the right people on the team is a critical step for Bain & Company as it focuses its recruiting efforts at top universities around the globe. Bain, which was named the number-one company in the United States to work for in 2019 by Glassdoor, identifies these universities as being able to effectively find (and sometimes prepare) individuals for management consulting. Bain also invests heavily in multiple rounds of interviews with new recruits as it looks for three skill sets: analytical and problem-solving skills, communication and client management skills, and team collaboration skills.

In the first round of interviews, recruits are largely tested on their analytical and problem-solving skills as they are asked to solve business cases during the interviews. The second round focuses more on whether recruits have the client and communication skills necessary and whether they will be effective team players. As part of the client and communication skill evaluation, interviewers assess whether the person has the appropriate degree of confidence and optimism without showing arrogance. They also assess whether a recruit can comfortably communicate with all sorts of people, from shop foreman to CEO. Finally, recruits must pass the airplane test: “Is this someone I would want to hang out with for six hours on an airplane?” “Is this someone I want to work on my team?”

Another way that Bain gets the right people is to watch them perform on a Bain team before they are hired as a full-time consultant. To do this, Bain invests heavily in a summer intern program, bringing in a large number of MBA and undergraduate students to work over the summer to see whether they have the right stuff (i.e. analytical skills, communication skills, and team collaboration skills). Thus, Bain puts potential team members on a simulated “bus ride” before putting them on the bus for good.

According to Mark Howorth, senior director of global recruiting for Bain, roughly two-thirds of new consultants hired have worked at Bain either as summer interns or as analysts (associate consultants) after graduating from college. This dramatically reduces the risk of getting the wrong people on the bus. Once Bain has determined that a person has the ability to be successful, it brings that person into an organizational environment that supports effective teamwork.

Bain's internal study of extraordinary teams found that lower-performing teams were generally larger and had multiple reporting relationships. Consequently, efforts are made to keep teams small and structures flat. The logic is that people work harder and are happier when they are given heavy responsibility and are not burdened by layers of management. Moreover, on a small team, individuals have more direction from supervisors and are less likely to get lost in the shuffle and end up frustrated and unproductive. Therefore, teams are generally organized to consist of only four to six members. These individuals report to a manager, who then reports to a partner, the end of the line of authority. All are closely involved in the work and are held accountable for team performance.

Bain devotes significant time to determining the right mix of people given the demands of the team project and the professional development needs of potential team members. The team assignment process begins with a discussion among the office staffing officer, partners or managers, and potential members. The staffing officer typically discusses the skills required to be successful on a particular client project with the partner or manager. Three issues are generally reviewed when a person is considered for a team:

- Does this person have the skills and experience necessary to help the client be successful in this particular assignment?

- Does this project fit with this person's skill plan and professional development needs?

- Will this person work well with the client, manager, and other team members?

The staffing officer in charge of case team assignments speaks with managers and potential team members before an assignment is made to make sure the fit is good. In most cases potential team members can refuse an assignment if they make a strong argument that they cannot answer these questions with a “yes.” By taking time in advance to consider these issues, Bain ensures that team members are considerably more committed to the team and are less likely to become frustrated and unproductive. As a result, management saves time by avoiding team problems down the road.

This may seem paradoxical, but while creating extraordinary teams is the overall goal, Bain doesn't lose sight of the fact that extraordinary teams are composed of successful and productive individuals. To ensure that individual needs are considered, professional development is a company priority. Managers and team members jointly develop skill plans to outline the skills that the team member needs to develop in order to advance in the organization.

Skill plans are prepared every six months with the manager providing coaching and feedback. Most managers also conduct a monthly or bimonthly lunch with each member to discuss professional development needs. The system is supported by a professional development department whose primary responsibility is to help employees with their personal growth and development. Team “buddies,” or colleagues, are assigned when a new member joins the company to ensure that he or she is properly integrated into the team. Remembering the individual is Bain's way of keeping its turnover among the lowest in the consulting industry.

Assessing Composition

Because composition is important for team success, we believe that organizations should periodically do an assessment to see if their methods for assigning team members support team development. The following worksheet provides an assessment for determining whether that foundation is in place.

Notes

- 1. L. C. McDermott, N. Brawley, and W. W. Waite, World Class Teams: Working Across Borders (New York: Wiley, 1998).

- 2. J. R. Katzenbach and D. K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 275.

- 3. G. M. Parker, Cross-Functional Teams: Working with Allies, Enemies, and Other Strangers (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003), 166.

- 4. F. P. Morgeson, M. A. Campion, R. L. Dipboye, J. R. Hollenbeck, K. Murphy, and N. Schmitt, “Are We Getting Fooled Again? Coming to Terms with Limitations in the Use of Personality Tests for Personnel Selection,” Personnel Psychology 60 (2007): 1029–1049.