5

CHANGE MANAGEMENT: HOW EFFECTIVE TEAMS IMPROVE THEIR PERFORMANCE

The fourth C refers to change, the key meta-competency in our model. High-performing teams are not only aware of what is impeding their performance but are able to take corrective action to solve their problems and achieve their goals. In this chapter, we discuss (1) the common problems found in teams and how to diagnose them, (2) how to determine whether the team itself can solve its problems or whether a facilitator or consultant is needed, and (3) the basic elements of programs designed to initiate change within the team. In Chapter 7 we will discuss in greater detail how organizations can put together team-building programs that are organization-wide.

Common Problems Found in Teams

Usually a team-building program is undertaken when a concern, problem, issue, or set of symptoms leads the manager or other members of the team to believe that the effectiveness of the team is not what it could be. The following symptoms or conditions usually provoke serious thought or remedial action:

- Failure to achieve team goals

- A reduction in productivity

- Unexplained increase in costs

- Increases in grievances or complaints from team members

- Complaints from clients about quality of the product or service

- Conflict among team members

- Confusion about assignments

- Lack of broad team support for decisions

- Decisions not carried out properly—lack of follow-through

- Apathy and general lack of interest or involvement of team members

- Lack of initiative, imagination, or innovation

- Ineffective meetings

- Problems with the team leader—high dependence on or negative reactions to the team leader

- Poor communication (people not speaking up or not listening to each other)

Most of these are symptoms; that is, they result from or are caused by other underlying factors that are the root causes of the problems. A loss of productivity, for example, might be caused by such factors as conflicts between team members or problems with the team leader. The following survey is one way to assess how a team is performing.

In some instances the team leader or other members of the team may not have the skills or experience to launch a team-building program. If that is recognized by the team leader and the team, an outside facilitator or consultant may be needed to help the team improve its performance. The following checklist provides some guidance concerning whether an outside person is needed to help the team with its efforts to manage change.

Team Building as a Process

Many people think of “team building” as a one-time fun retreat. They imagine the team going somewhere remote to do “trust falls” and other bonding activities, then returning to work and conducting business as usual. Those who think about team building in this way generally see no long-term success. Team building should be thought of as an ongoing process, not as a single event. Some organizations actually institutionalize team development as part of their ongoing activities. For example, Bain & Company does team building on a monthly basis to ensure that team problems are quickly identified and resolved.

The ability for a team to be aware of its strengths and weaknesses and then take action to improve its performance is a “meta-competency” that great teams have. This ability allows them to systematically evaluate and change the way the team functions. This means changing team processes, values, team member skillsets, reward systems, or even the resources available to get teamwork done. The philosophy one should have about team development is the same as the philosophy behind what the Japanese call kaizen, or continuous improvement: the job is never done because there are always new bottlenecks preventing even better team performance.

The team development process often starts with a block of time devoted to helping the group look at its current level of functioning and to devise more effective ways of working together. In fact, one approach to doing this is to follow the kaizen approach and have the team identify the biggest bottleneck to improved team performance and then develop a plan to address and fix that bottleneck. This initial sequence of data sharing, diagnosis, and action planning takes time and should not be crammed into a couple of hours. Ideally the members of the team should plan to meet for at least one half day, one full day, or even two days, for the initial program. A common format is to meet for dinner, have an evening session, and then meet all the next day or for whatever length of time has been set aside.

This meeting is not to focus on what the team will do, but how the team will do it. This is sometimes difficult because oftentimes people want to dive right into getting the work done, not realizing that they will accomplish much more if the team has established how they will get it done. For this reason, it is customary to hold the initial team development program away from the work site. The argument for this is that if people meet at the work location, they will find it difficult to ignore their day-to-day concerns in order to concentrate fully on the goals of the program. Thus, most team-building facilitators recommend having team development programs at a location where they can have people's full time and attention.

Most team-building facilitators also prefer to have a longer block of time (even up to three days) to get the team engaged and really make progress in establishing a team development program. Of course, this may not be practical in some situations. Since we are thinking of team development as an ongoing process, it is possible to start with shorter amounts of time regularly scheduled over a period of several weeks. Some teams have successfully conducted a program that opened with an evening meeting followed by a two-to-four-hour meeting each week for the next several weeks. Commitment to the process, regular attendance, high involvement, and good use of time are all more important than length of time.

Use of an Outside Facilitator or Consultant

Team leaders often ask, “Should I conduct the team development effort on my own, or should I get an outside person to help us?” As we noted previously, an “outside person” can mean a consultant from outside the organization or an internal consultant who is employed by the organization, often in human resources or organization development and with a background in team development.

Ultimately the team leader is responsible for team development. This is an important concept to remember. Some team leaders think that by bringing in an outside consultant they no longer have primary responsibility for the development of the team. However, the consultant should be seen as assisting the team leader and the team, not as replacing the leader's responsibility to lead the team. The consultant's job is to get the process started and to be a neutral “sounding board” for the team leader and team members. The use of a consultant is generally advisable if a manager is aware of problems, feels that he or she may be one of those problems, and is not sure exactly what to do or how to do it but feels strongly enough that some positive action is necessary to pull the team together to improve performance.

The Roles of Team Leader and Consultant

Ultimately the team leader or manager is responsible to develop a productive team and develop processes that will allow the team to regularly stop and critique itself and plan for its improvement. It is the leader's responsibility to keep a finger on the pulse of his or her team and plan appropriate actions if the team shows signs of stress, ineffectiveness, or operating difficulty.

Unfortunately, many team leaders and managers have not been trained to do the data gathering, diagnosis, and planning and take the actions required to maintain and improve their teams. The role of the consultant is to work with the manager until the manager is capable of incorporating team development activities as a regular part of his or her managerial responsibilities. The manager and the consultant (whether external or internal) should form their own two-person team in working through the initial team-building program. In all cases, the manager or team leader will be responsible for all team-building activities, although he or she may use the consultant as a resource. The goal of the consultant's work is to leave the leader capable of continuing team development without the assistance of the consultant or with minimal help.

The Team-Building Cycle

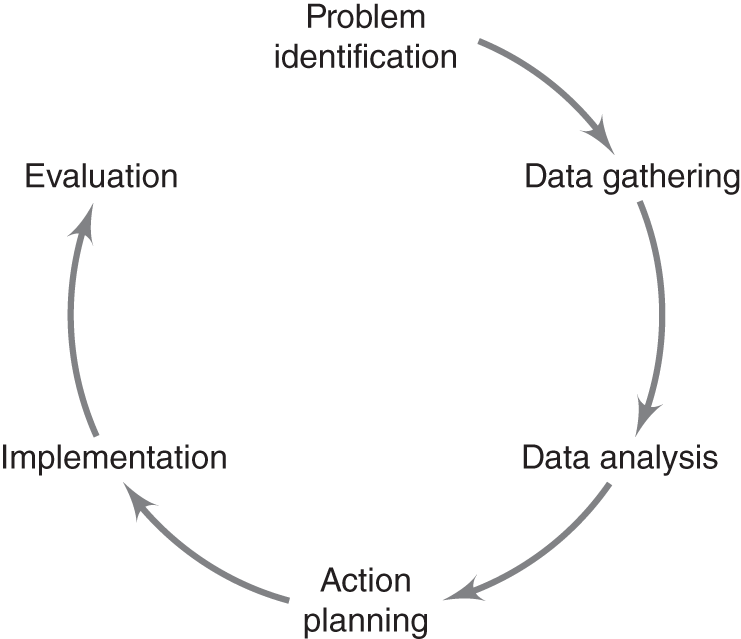

Ordinarily a team-building program follows a cycle similar to that depicted in Figure 5.1. The team-building cycle typically begins when someone recognizes one or more problems that should be addressed by the team. After identifying the problem the next step is to gather data to determine the root causes. The data are then analyzed and a diagnosis is made. After the diagnosis, the team engages in appropriate planning and problem solving. Actions are planned and assignments made. The plans are put into action and the results honestly evaluated.

Figure 5.1 The Team-Building Cycle

Sometimes there is no clear, obvious problem. The concern is then to identify or find the problems that may be present but hidden along with their underlying causes. The team leader must continue to gather and analyze the data, identify the problems and the causes, and then move to action planning. Team members work together to carry out the program from the time the problem has been identified through some form of evaluation. This process then iterates until the problem has been resolved.

We'll now address, in more detail, the steps in the team-building cycle.

Data Gathering

Because team building encourages a team to do its own problem solving, and given that a critical condition for effective problem solving is accurate data, it is extremely important to gather valid data on the hypothesized causes behind the symptoms or problems originally identified. A consultant initially may assist in the data gathering, but eventually a team should develop the ability to collect its own data as a basis for working on its own problems. The consultant should be part of the data gathering to ensure that the methods of gathering data aren't biased toward one point of view or one solution. In cases where trust is low in the team and data gathered by other team members may be viewed with suspicion, the consultant may need to collect all the data for the team. The following are some common data-gathering methods.

Surveys One of the most common approaches to gathering data is to conduct a survey of all team members. Surveys are helpful when there are relatively large numbers of team members or members would be more open in responding to an anonymous survey. It also can be helpful to use a survey if you want to compare the issues and problems facing different teams in an organization.

There are two general types of surveys: open- and closed-ended surveys. An open-ended survey asks questions such as: What do you like about your team? What problems does your team need to address? and What suggestions do you have to improve the team? Team members can give their responses in writing. The team leader or consultant summarizes these responses and presents them to the team in a team-building session. It may be somewhat messy to summarize such raw data, but it often helps to read the actual views of the team members to better understand the issues and how the members are feeling.

Closed-ended surveys force the person responding to choose a specific response. Most of the surveys in this book are closed-ended (but often with one or two open-ended questions at the end). Closed-ended surveys make tabulating the results easy and statistical comparisons possible. However, they may miss some of the important dynamics and problems of a team. Closed-ended surveys are a useful starting point, however, to create awareness of the problems facing a team and begin a discussion of how to solve those problems. We have found that the team-building checklist in this chapter and the Team Context (see Chapter 2), Team Composition (see Chapter 3) and Team Competencies (see Chapter 4) scales are helpful surveys to gather data about a team.

Interviews At times a consultant can perform a useful service by interviewing the members of the team. The manager or team leader could conduct such interviews, but in most cases, team members will be more open in sharing data with someone from outside the team. The consultant tries to determine the causes behind the problem in order to pinpoint those conditions that may need to be changed or improved. In these interviews the consultant often asks the following questions:

- Why is this team having the kinds of problems it has?

- What keeps you personally from being as effective as you would like to be?

- What things do you like best about the team?

- What changes would make the team more effective?

- How could this team begin to work more effectively together?

Following the interviews, the consultant frequently does a content analysis of the interviews, identifies the major themes or suggestions that emerge, and prepares a summary presentation. At the team-building meeting, the consultant presents the summary, and the team, under the leader's direction, analyzes the data and plans actions to deal with the major concerns.

Some consultants prefer not to conduct interviews prior to the team-building meeting and do not want to present a data summary. They have found that information shared in a private interview with a consultant is not as readily discussed in the open, with all other team members present, especially if some of those members have been the object of some of the interview information. Some consultants have painfully discovered that people often deny what they said in the interview, fight the data, and refuse to use what they said as a basis for discussion and planning. At times it may be appropriate for the consultant to interview people privately to understand some of the deeply rooted issues but still have people present their own definitions of the problems in an open session.

One question often arises about interviewing: Should the interviews be kept anonymous so that no one will be identified? We have found that if data are gathered from a team and those data are then presented to that team, team members often can figure out who said what. Keeping sources anonymous is often difficult, if not impossible. Thus, we typically say to a team member before starting an interview: “You will not be personally identified in the summary we present back to the team, but you must be aware that people might recognize you as the source of certain data. Thus, you should respond to the questions with information that you'd be willing to discuss in the team and might possibly be identified with. However, if you have some information that is important for us to know but you don't want it to be reported back, you can give such information ‘off the record.’ This information won't be reported, but it might prove useful to us to better understand the team's problems.” We have found this approach helpful in getting team members to open up and share information with us about the team. It also encourages team members to own their own feelings and be willing to discuss them in the team.

Team Data Gathering An alternative to surveys and interviewing is open data sharing in a team setting. With this method, each person in the team is asked to share his or her views (on a particular problem or issue) publicly with the other team members. The data shared may not be as inclusive as data revealed in an interview, but each person feels responsible to own up to the information he or she presents to the group and to deal with the issue raised. To prevent forced disclosure, one good ground rule is to tell people that they should raise only those issues they feel they can honestly discuss with the others. They then generally present only the information they feel comfortable discussing; thus, the open sharing of data may result in less information but more willingness to “work the data.” It may be helpful to systematically discuss barriers to effective team functioning that may exist in the other four Cs: team context, team composition, team competencies, or team leadership.

With a team data gathering format, each person presents his or her views on what keeps the team from being as effective as it could be or suggests reasons for a particular problem. Each person also describes the things he or she likes about the team, hindrances to personal effectiveness, and the changes he or she feels would be helpful. These data are compiled on a flipchart or whiteboard. (In another variation, data for a large team could be gathered and shared in subgroups.) Then the group moves on to the next stage of the team-building cycle, data analysis.

Diagnosis and Analysis of Data

With all the data now available, the manager and the consultant work with the team to summarize the data and put the information into a priority listing. The following summary categories could be used:

- Issues that we can work on in this meeting.

- Issues that someone else must work on (and identify who the others would be). For example, context issues, such as changing reward systems, often need to be addressed with people who are not on the team.

- Issues that apparently are not open to change—that is, things we must learn to accept or live with.

Category A items become the top agenda items for the rest of the team-building session. Category B items are those for which strategies must be developed by involving others. For category C items, the group must develop coping mechanisms. If the manager is prepared, he or she can handle the summary and sort the data into these three categories. If the manager feels uneasy about this, the consultant may function as a role model to show how this is done.

The next important step is to review all the data and try to identify underlying factors that may be related to several problems. A careful analysis of the data may show that certain procedures, rules, or job assignments are causing several disruptive conditions.

Action Planning

After the agenda has been developed out of the data, the roles of the team leader or manager and the consultant diverge. The leader should move directly into the customary role of group leader. The issues identified should become problems to solve and the team leader should lead the team in creating action plans to address the problems.

While the leader conducts the meeting, the consultant functions as a group observer and facilitator. MIT professor Edgar Schein has referred to this activity as “process consulting,” a function that others in the group also can learn to perform.1 In this role, the consultant helps the group look at its problem-solving and work processes. He or she may stop the group if certain task functions or relationship functions are missing or being performed poorly. If the group gets bogged down or steamrolled into uncommitted decisions, the consultant helps the team look at these processes, why they occur, and how to avoid them in the future. In this role, the consultant trains the group to develop better problem-solving skills.

Implementation and Evaluation

If the actions planned at the team-building session are to make any difference, they must be put into practice. Ensuring that plans are implemented has always been a major function of management. The team leader must be committed to the team plans; without commitment, it is unlikely that a leader can effectively hold people responsible for assignments agreed on in the team-building meeting.

The consultant's role is to observe the degree of action during the implementation phase and be particularly active during the evaluation period. Another data-gathering process now begins to evaluate the impact of the team's change program. It is important to see if the actions planned or the goals developed during the team-building sessions have been achieved. Again, this ultimately should be the responsibility of the leader, but the consultant can help train the manager to carry out an effective program evaluation.

The team leader and the consultant should work closely together in any team development effort. It is ineffective for the leader to turn the whole effort over to the consultant with the plea, “You're the expert. Why don't you do it for me?” Such action leads to a great deal of dependence on the consultant, and if the consultant is highly effective, it can cause the leader to feel inadequate or even more dependent. If the consultant is ineffective, the leader can then reject the plans developed as being unworkable or useless, and the failure of the team-building program is blamed on the consultant. Team leaders must take responsibility for the team-building program, and consultants simply help them plan and take action in unfamiliar areas where they may need to develop the skills required to be successful.

The consultant must be honest, aggressively forthright, and sensitive. He or she must be able to help leaders look at their own leadership style and its impact in facilitating or hindering team effectiveness. The consultant needs to help group members get important data out in the open and keep them from feeling threatened for sharing with others. The consultant's role involves helping the group develop skills in group problem solving and planning. To do this, the consultant must have a good understanding of group processes and be able to help the group look at its own dynamics. Finally, the consultant's job is to build skills in the team so that the team is able to solve problems independently and no longer needs the help of a consultant.

Note

- 1. E. H. Schein, Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1988).