22

Keep Asking Why

“Curiosity is lying in wait for every secret.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Don't come to me with questions, come to me with solutions.” Not the words of some impatient boss, but of your own mind. On second thoughts then, they are the words of an impatient boss.

Our brain has a lot on its plate, so it wants to solve problems quickly and get on to the next thing.

It was different when we were young. Our brains were full of questions it needed the answers to.

We ask about 40,000 questions between the ages of two and five. Four being our most inquisitive age when we ask about three hundred questions per day.

But these were questions we needed answers to in order to understand the world around us. Once children get older their questioning starts to tail off. A lot of people lay the blame on a school system that seems to value answers more than questions. I'm sure that's part of it, but I also think we don't need the answers as much.

From an evolutionary point of view our brains need just enough information to keep us safe and be able to function successfully in society. The answers to any other questions are just an added luxury.

But if you want to be a great problem solver, you need to cultivate a truly questioning mind.

You need that natural curiosity of a four-year-old, but you want to be asking the questions that have never been asked before.

Take Isaac Newton; he didn't have a to-do list, he had a why list.

When he was a student at Cambridge, he was uninterested in the set curriculum. At 19 he drew up a list of questions under 45 headings. His aim was to constantly question the nature of matter, place, time, and motion.

He said he came up with the law of universal gravitation, “By thinking on it continually.” It wasn't just because an apple hit him on the head.

Like Einstein who said, “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious,” he didn't believe he was a genius.

Newton's style was hard slog.

For example, he bought Descartes' Geometry and read it by himself. When he got through two or three pages and couldn't understand any further, he began again. He continued to do this until he truly understood what Descartes had to say on the subject.

It's the struggle to work things out that creates a great mind, not just having the answers.

I don't think we can just blame schools and society for making us less inquisitive. We need to create our own desire for how and why things happen.

Leonardo da Vinci even created a word for it: Curiosita – an insatiably curious approach to life and unrelenting quest for continuous learning. That's what made him such a great thinker, he wasn't just interested in one subject. He was a painter, but he was also a sculptor, architect, scientist, musician, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, astronomer, cartographer, botanist, historian and writer.

As well as being curious, it's also very important to cultivate a thoughtful mind instead of a quick one.

Darwin, like Einstein and Newton, relied upon perseverance and continual reflection, rather than memory and quick reflexes. “I have never been able to remember for more than a few days a single date or line of poetry.” Instead, he had “the patience to reflect or ponder for any number of years over any unexplained problem. At no time am I a quick thinker or writer: whatever I have done in science has solely been by long pondering, patience, and industry.”

In fact, if you look at Darwin's notebooks, you will see that he already had the information he needed to come up with his theory of evolution. He had all the jigsaw pieces; he just needed time to put them together.

Why, oh why, oh why?

Millions of people have been on walks in the countryside with their dogs and had to pick burrs out of their dogs' fur afterwards. But how many would have wondered why the burrs kept their stickiness.

It took the questioning mind of George de Mestral to ponder it and then put one of the burrs under a microscope and see hundreds of “hooks” that caught on anything with a loop, like curly hairs of a dog's coat. He then took this discovery and used it as the basis of his invention Velcro.

But having this questioning nature isn't just about discovering new ideas; it's also a way of questioning something that already exists, that isn't working.

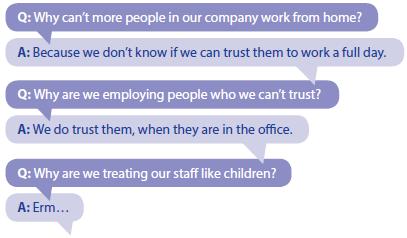

Ricardo Semler, CEO of Brazilian company Semco, famous for its radical industrial democracy, suggests that one way to get to a greater wisdom is to simply ask three “Whys?” in a row about everything you are doing.

He says, “The first ‘Why?' you always have a good answer for. Then the second ‘Why?' starts getting difficult to answer. By the third ‘Why?' you realize that, in fact, you really don't know why you're doing what you're doing.” Semler says that by asking “Why?” three times, you start to get clearer about who you are and why you are here.

Here's an example of how the “three whys” get to the heart of the problem:

With an inquiring mind you don't know where you're going or what the future holds. But what you do know is that when you get there it'll be a lot more interesting.