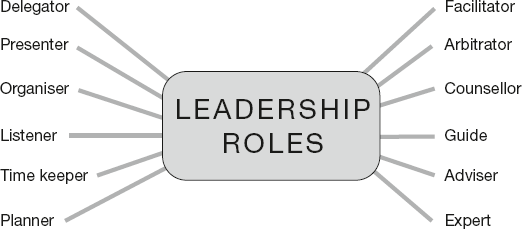

Having set the tone, you are now ready to proceed with a Brilliant Meeting in a professional and motivational atmosphere, where participants can give their full attention and contribute honestly and freely in order to achieve the required meeting outcomes. In order to lead a Brilliant Meeting, you may need to take on many varied roles.

Managing the agenda

Ensure that all participants have a hard copy of the agenda.

Having allocated timings for each agenda item, try to keep to them as closely as possible. The role of time keeper within a meeting can either be incorporated into your role as meeting leader, or it can be delegated to one of the participants.

The ultimate consequence of poor time management is an incomplete meeting that can damage your own credibility, and which effectively labels the meeting as ‘a waste of time’. You cannot stop a discussion or presentation bluntly mid-flow just because the time allocated has been reached. Agenda items are managed by keeping participants aware of time constraints when necessary, and taking positive actions to keep the meeting on track and to time.

Keeping the meeting on track and on time

Summarise, conclude and suggest moving on:

‘I think we are almost finished on this point, does everyone agree with Duncan’s proposal?’

Suggest that this issue is removed from this meeting and ‘parked’ until the next meeting:

‘As this item needs further input and discussion, can I suggest that we defer to a future meeting and allocate an appropriate amount of time to it?’

Suggest that this issue is dealt with by a ‘sub group’ and presented at a future meeting:

‘More detail and discussion is needed than we have time for today. Can I suggest that you three convene a separate meeting and then circulate the briefing notes in order that we can discuss your findings at the next meeting?’

Suggest an extension to the meeting, if the room is available:

‘As more detail and discussion is needed than I had originally allocated time for, would everyone be able to stay for a further 45 minutes to complete the meeting?’

Countdown cards

For meetings where formal timed presentations are being given, consider using A4 laminated flashcards with ‘3 minutes’, ‘2 minutes’, and ‘1 minute’ printed on them in large text. Either you or the designated timekeeper can now hold these up to presenters, thereby alerting them to the impending end of their allocated time without directly interrupting their words or the concentration of those listening to them.

Directing the note taker

Chapter 12 provides guidance for the note taker. However, during the course of the meeting it might be necessary for you to specify if a different level of detail should be documented in the meeting notes.

Managing and encouraging contributions

Participants have been selected based on their individual expertise, experience and personality to work together to achieve the meeting objectives. Whether you need to coerce or curtail contributions, getting the best from your individual participants may involve some or all of the following techniques.

Brainstorming

This is a group technique designed to generate a large number of creative ideas for the solution to a problem. At this stage you are collecting ideas to evaluate later and, so long as they are focused on the subject, responses should not be restricted, but instantly recorded without any additional comment. The next stage is to evaluate each response in order to determine which are worthy of further consideration and idea development.

Round robin

To make sure everyone is given the opportunity for individual input, start the discussion by giving everyone, in turn, a precisely defined amount of time to share their initial thoughts with the group. This exercise can be used several times during a meeting so always start off with a different participant, and move around the table clockwise giving everyone their say. You might be surprised to find that there is already a consensus or even unanimity on an issue. More likely you will need to summarise and go back to individual participants to expand on their points.

Congratulate or critique contributions, ignore individuals

The aim here is to disconnect the contribution from the contributor so that, if a suggestion is in need of criticism, the personality can be removed. This is a very difficult skill, bordering on counselling, that would not be appropriate for a high-powered business meeting, but could deliver great value to a meeting with less confident participants.

Identifying non-verbal signs

Whilst the quieter members might not speak up willingly, you should be able to gauge from their body language whether they have something of value to contribute. They might be leaning forward in their seat, or perhaps nodding or shaking their head, in which case you can direct a question to them for their opinion. If they have not spoken out much before, reaffirm their comments in a positive way (remember to congratulate the comment, not the individual).

‘One at a time please’

Whether participants are being argumentative or simply just eager to have their contributions heard, having more that one person speaking at once does not make for a good meeting environment. These simple assertive words will allow you to take control of contributions from a larger group, and suggest some respect is forthcoming from those that are being just plain rude.

Remind participants of the Brilliant Meetings ACTION PLAN – ‘Imagine the CEO is always present’, and ask them to allow speakers to continue without interruption. More tact will be required if the persistent offender is someone senior, as this will be more difficult to request.

Taking back control from a colleague in a senior position

If a situation arises where you need to regain control, be ready to leap in when a pause occurs, with something along the lines of:

‘Thank you, Duncan, that’s a great example of one way in which we might proceed in this instance. However, I’d like to get back to the specifics of . . .’ or alternatively,

‘Thank you, Duncan, that’s a great suggestion, but more discussion is needed than we have time for today. Can I suggest that this is added to the agenda for the next meeting?’

This way you are publicly thanking them for their contribution and simultaneously steering the meeting back on track.

If you had been sitting, then stand as you address the situation. If you had been at the side or back of the room, move forward as you speak to claim back your meeting.

If the digressing tendencies of your senior colleague are well known in advance, then you can make arrangements to deal with it; assign the role of time keeper to another participant, and have an arranged sign for requesting them to audibly warn you when the time for the agenda item is almost over. You can then interject, citing this as the reason for wrapping up the disruptive contribution, and move the meeting on.

Questions/comments only via the leader

With smaller, more intimate meetings, this approach could be seen as very authoritarian but, for larger departmental or organisational meetings, it almost certainly will be an essential technique for keeping the meeting flowing.

Questions

Questions are a fabulous method of encouraging information from participants but, for this to be effective, you must practise your questioning techniques and use them where and when appropriate.

There are several great reasons to ask questions of your participants:

Individual or group questions

Make it clear if you are posing a question directly to an individual, to the group as a whole, or whether it is open for any member of the group to respond.

- If directed at an individual, start the question with their name:

‘Duncan, how will this new procedure affect your department?’ - If directed at the whole group, maybe you want a show of hands on a proposal:

‘Hands up who thinks we should talk again with the supplier?’ - Or if you simply are looking for a response from the group:

‘Who can tell me what the impact on their department will be?’

Questioning techniques

It is important to understand question types because, when phrased correctly, these will determine the length and detail of the answers given, providing you with the information you were seeking.

The great news is that there are basically only two types of questions to master. An open question generally produces answers with more detail, whilst a closed question generally results in a single word (or at least a shorter) answer.

Open questions

Ask open questions when you want to ‘open up’ dialogue and receive longer, more detailed answers. Open questions generally begin with ‘what’, ‘why’, ‘how’, ‘who’ and ‘when’. An open question asks the respondent for his or her knowledge, opinion or feelings. ‘Tell me’ and ‘describe’ can also be used in the same way as open questions. Be careful when asking ‘why’ questions as too many could come across as confrontational.

Here are some examples:

- What happened at the meeting?

- Why did he react that way?

- Tell me what happened next.

- Describe the circumstances in more detail.

Open questions are good for:

- seeking an opinion – ask a subjective question:

‘What do you think about the proposed changes?’ - identifying specific information – ask an objective question:

‘What was the percentage gross margin achieved last year on this product?’ - collating ideas for actions – ask a problem solving question:

‘What are your next steps in resolving this recruitment issue?’

Enabling contributions from the quieter members of the group

If you know that a participant has vast experience to contribute, but they are not doing so – ask them a direct question that you know they will be able to answer. It is not the information to the easy question that is of most importance, but getting them conditioned to speaking up now, so that when the difficult questions arise, they are confident about speaking.

Closed questions

A closed question usually begins with: ‘are’, ‘who’, ‘did’, ‘will’, ‘is’, ‘do’, ‘can’, etc., and you use these to search for short answers, maybe even a single word such as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘don’t know’ or the factual answer. Of course this will not stop the ‘Yes, but you should be . . .’ but it will minimise it.

For example:

- ‘Are you happy with the meeting agenda?’

- ‘Is the room temperature ok for everyone?’

- ‘Did you complete the pre-meeting preparation?’

Closed questions are good for:

- testing understanding:

‘So, if I understand this correctly, your group have concluded that the telephone should be answered within three rings, and not four rings as was previously agreed?’ - summarising and concluding a discussion or making a decision:

‘Now we know the facts, are we all agreed this is the right course of action?’ - identification:

‘Who is responsible for reporting back on the actions from the last meeting?’

Asking the correct type and style of question makes it easier for the people around you to provide the appropriate answer.

Do not expect to become an instant expert in questioning techniques

Effective questioning is a skill that needs to be nurtured and practised. You can practise these skills in a social environment; try using different types of questions with your family when enquiring about holidays/work/school, etc.

‘The uncreative mind can spot wrong answers, but it takes a creative mind to spot wrong questions.’

Anthony Jay

Dealing with challenging behaviour

Most meeting participants focus well on dealing with the topics under discussion. There will, however, be occasions when the behaviour experienced is less than ideal, unhelpful even. Quite often those participants even may be unaware that they are being unhelpful so, in case you come across examples of these behaviours during your meetings, here are some pointers for recognising and dealing with them.

Personalities displayed in meetings

The know-all

The know-all tends to be the most vocal, coercive and predictable and is always full of the ‘right’ answers. They tend to be a little overpowering and aggressive, quick to offer solutions because of their impatient nature. They will always know best because ‘I have done this before’.

Deal with this by thanking them quickly for the benefit of their experience, and ‘park’ their suggestions, then direct the same question to another participant for their opinion.

The silent agreer

The silent agreer can be identified by almost constant nods of the head, and barely audible ‘Mmmm’ or ‘Yes’. Eye contact and contributions are kept to a minimum, but do not be fooled, the lack of participation could be influenced by a shy disposition, or an unprepared participant.

Deal with this by encouraging contributions from them in a non-confrontational manner. Direct a question to them to which you know they have the answer.

The negative type

The negative type is also loud and opinionated, compelled to tell everyone why these ideas and suggestions are doomed to failure. It is unlikely that they will be open to new ideas, because they are fuelled by a negative attitude.

Deal with this by asking them to propose solutions that help, rather than just stating why ‘something will not work’.

The ‘off at a tangent’ type

The ‘off at a tangent type’ normally has good intentions, but a meeting can be hijacked with personal anecdotes and by-the-way conversations. They tend to get carried away with PowerPoint™ presentations containing 67 slides, with copious amounts of writing, which they then proceed to read verbatim from the screen.

Deal with this by not letting them deviate from the point, politely but firmly. Try posing a question to the group, asking if they feel these issues are relevant to the present meeting.

The ‘whispering’ type

The whispering type will frequently hold side conversations during the meeting, which often results in them missing valuable information and distracting other participants. These conversations are often unrelated to the meeting topic, making this behaviour even more disruptive.

Deal with this by aiming non-verbal signals in their direction, such as ‘finger over lips’. If this does not work, pause the meeting and reinforce why it is essential that only one person speaks at a time. Another alternative is to ask them to share their comments with the group, but this can result in conflict if they insist on keeping their comments to themselves.

BEHAVE – Use the following guidelines during a meeting if you are faced with challenging behaviour:

Be calm. Do not get involved emotionally yourself.

Engage the individual privately, during a break or generally during the meeting.

Have empathy with the situation.

Ask for a summary from them and listen without interruption.

Verify the root of the problem by asking a question for clarification.

Establish agreement on how to handle the root cause in order to move forward.

Recognising body language

Body language is an important part of communication that can constitute 50 per cent or more of what we communicate. Communication occurs constantly during a meeting. Even if only a small minority of participants are speaking, almost everyone (if not everyone) will be exhibiting body language signals that divulge what they are actually feeling inside.

The more you can recognise and understand how to read the body language signs that your participants are subconsciously communicating to you, the greater the influence you will have over them, to either curtail or bring in contributions. Here are some very basic indicators that will help to further your understanding.

- An erect posture indicates interest and alertness.

- Sitting with arms crossed, across the chest, indicates that the person is putting up a subconscious barrier between themselves and others.

- A ‘nodding’ participant is in full agreement with you.

- A person wringing their hands is indicating concern.

- A shoulder shrug signals that they do not believe what has been said.

- An excessive amount of leg movement indicates nervousness.

Regular meetings at work can become so routine that we forget the importance of our own body language, and that of the others around us. In addition, if our rapport with colleagues is familiar and friendly, we can very easily lose track of the fact that we are still in a professional setting and should conduct ourselves accordingly.

Dealing with conflict situations

Truly difficult situations rarely arise; however, disagreements and differences in meetings should be viewed as potentially very useful as they can actually drive discussions forward and generate valuable information.

Where differences of opinion are not relevant to the meeting, quick decisive action needs to taken by you to keep the meeting on track. If there are ‘hidden-agendas’ between participants, then the resolution for these has to be outside of your meeting, and you should inform participants of this directly.

If there is conflict or resistance within the group that is genuinely within the remit of the meeting, then you must now focus on changing negative problematic energy in to positive purposeful energy. The group needs to be engaged and empowered to transform the conflict in to decisive, practical actions. Try these basic guidelines, remembering all the time that you must not get directly or emotionally involved.

- Ask the person with the problem to come forward and write it up. Now with the word(s) clearly displayed for the whole group to see, what suggestions can you draw out to deal with it? Have the person whose perceived problem it was stay and write up the solutions offered. Ask them if there are any suggestions that they now think could work.

- Re-focus the group’s thinking on the solutions – not the problems. Continually ask questions such as, ‘How can we deal with this?’, ‘What does a successful solution look like?’, ‘How will this fulfil our meeting purpose and objectives?’

Interruptions

An interruption can occur for any number of reasons – and with it comes an unwanted break in the meeting which, it has been suggested, can take upwards of 10 minutes to recover fully from. The biggest accidental interruptions can be avoided with planning and management.

- Mobile phones should be turned off.

- If you are not using video or audio conferencing, but have this equipment in the room, have these set to ‘Do Not Disturb’ modes, and then you cannot be accidentally dialled.

- Use clear signage indicating that a meeting is ‘in progress’.

Comfort breaks

This is one of the terms we have adopted – along with ‘bio break’ – as a euphemism for going to the toilet and, for longer meetings, breaks have already been scheduled into your agenda.

One thing to be aware of is that a participant sitting cross-legged desperate for the toilet will not be a good participant. Knowing they have got at least 20 minutes to wait for a scheduled break can be an anxious time. Some meetings have a ‘go-when-you-need-to’ policy, for which there are advantages and disadvantages:

- Participants could use it as a cover to leave the room specifically to check email or phone messages.

- A key part of the content could be missed – although you as leader can manage this by asking the contributor to wait until everyone is back in the room or to repeat it.

- Just knowing that they can get up and go to the toilet at any time will put some people at their ease, and thereby increase their effective participation.

- You can announce an unscheduled five-minute ‘comfort break’ if any of the participants are getting out of hand and you need to diffuse the situation. Maybe the break itself will do the trick, or you can direct them to take five minutes outside of the meeting to sort their problem out – if it is not relevant to your meeting.

You will have to decide how you want to manage this necessary occurrence during prolonged meetings.

Impromptu meetings

Many meetings will occur without advance preparation of an agenda, participant list and presentations, etc., just because of general business events. In these circumstances it is still important for all participants to share and understand the meeting purpose and objectives.

If you do nothing else, take a few minutes at the start of such meetings to consider what you want to achieve, and therefore what needs to be covered. This will give you a meeting structure to follow, and allow you to evaluate the effectiveness of even an impromptu meeting by measuring the outcomes against the initial objectives.