Is the traditional business plan dead? Maybe. At least some of the conventional assumptions about this classic piece of business writing need to die.

If you’re seeking a conventional loan or a contribution from an angel investor, then you’ll certainly need some kind of document to show the value of the investment opportunity you’re offering. But exactly what that document should look like varies greatly from business to business and investor to investor.

In this chapter, we’ll focus on business plan requirements for banks, but many of the insights apply to angel investors as well. Although templates for business plans abound, you’ll discover that there’s really no one-size-fits-all structure for an effective business plan. Like all the other types of writing we’ve explored so far, a business plan performs best when it caters to the particular interests of the target audience.

So if you’re not going to get a template from this chapter, what will you take from it? You’ll learn what a business plan is and what it isn’t so you can shape a document tailored to your lender. You’ll also learn how to create a logical argument, a compelling business case, and a concise executive summary of your plan.

The Purpose of a Business Plan

As a manager in the Commercial Banking division of CIBC (the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce), Kyle Rogers spends a lot of his time paging through business plans from a wide range of industries. His client list includes businesses to which the bank has loaned between about 1 and 5 million dollars.

For him, the business plan is a tool that needs to answer three key questions:

•What is the opportunity?

•Why is it significant?

•How will the business pay the bank back?

Ideally, the plan provides focused, well-supported answers to each of those queries—without drowning the reader in irrelevant details.

In Kyle’s experience, a five page business plan can outshine a 20-, 50-, or even 100-page document. Kyle wants to be able to access key information quickly, not root through volumes of unnecessary background. In fact, excessive length can kill a plan’s success.

“We don’t need to know the business as well as the business owner,” Kyle explains. What’s needed? “A smaller number of pages and more thoughtful analysis.”

Kyle recommends that entrepreneurs sit down with the lender as early in the application process as possible. “It’s never too early to meet,” he says. An early conversation allows you to figure out exactly what information the bank will be looking for in a plan, based on the state of the business, the industry, and other factors. With this input, you can then create a brief, customized plan addressing the precise points that will make or break your case.

Kyle shakes his head over applicants who go to great effort, and sometimes great expense, developing beefy business plans that completely miss the mark. For instance, he recalls one applicant who assembled pages of in-depth documentation to verify a contract with a major client. In the end, all that paper work did nothing to further the applicant’s case. In fact, it pointed up a major risk: most of the applicant’s business depended on the single (well-documented) client. Instead of describing all the ins and outs of his relationship with his major client, the applicant should have presented a risk mitigation plan showing how his business could cope with the sudden loss of that client.

The real job of a business plan is to present a compelling analysis of your business numbers, showing that the business will make enough money to pay back the loan, on schedule. The sooner you’re able to meet with the bank to share some background about your business and your initial financial projections, the better equipped you and your accountant will be to answer potential objections and wave away any red flags the bank perceives. Starting the lending process with a conversation enables you to get to know your audience so you can attune your writing to their needs, interests, and biases rather than simply filling out a template that may or may not suit your readers or your situation.

Understand What a Business Plan Isn’t

The name “business plan” creates the misleading impression that the document’s job is to describe or explain how your business will operate. If you’re creating a business plan for internal purposes, then it will indeed function as a conventional plan, providing a road map for you and your team to follow. But a business plan written for a lender actually plays a different role. As we’ve seen, it must show why and how your business will succeed. It must present a persuasive argument, building a convincing business case.

A business case differs from a “business story,” which is a term we hear a lot these days, so much so that it’s turned into a jargon term. People use “story” or “storytelling” to describe the structure of pitches, proposals, analytical reports, and various other kinds of documents, business plans among them. But that widespread labeling can prove misleading, especially in the case of business plans. A persuasive business plan includes some elements of narrative, but its overarching form must follow the logical structure of argumentative writing.

If you want to construct a compelling business case, you must put story in its proper place. Story can show how your company has evolved into its current state, and as in a pitch deck, it can enable readers to imagine your future success. But within the context of a business case, story supplements a persuasive argument; it doesn’t carry the main weight.

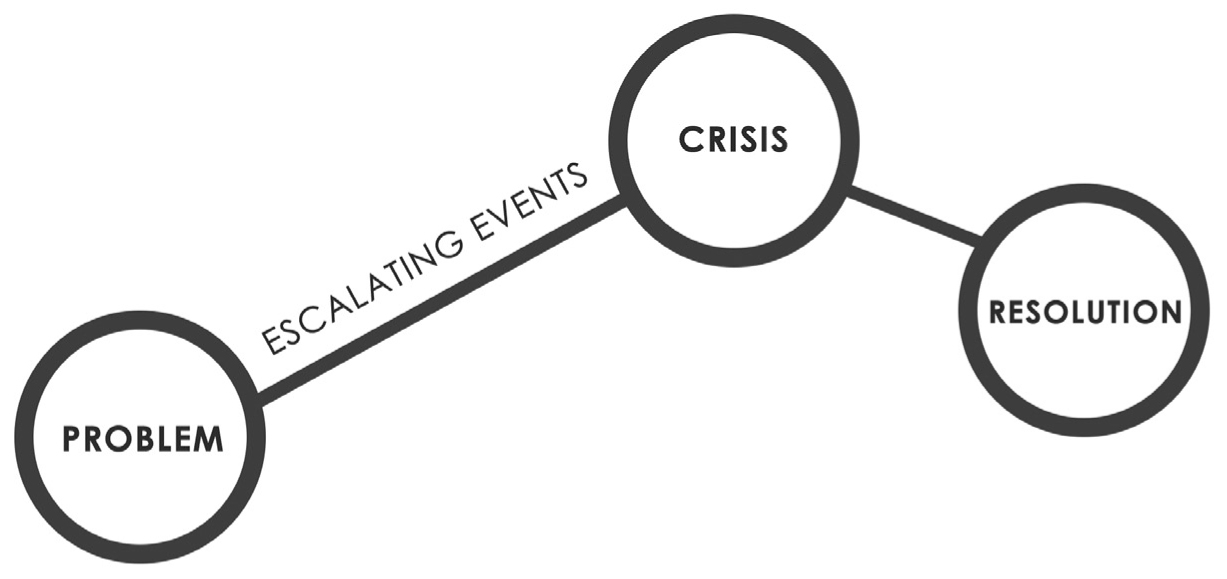

It’s important to recognize the difference between story and argument because the two modes of writing follow two different structures. A story presents a series of events, starting with an initial problem and then developing through a string of escalating incidents until some sort of crisis happens, followed by a resolution. Its linear structure looks like the one in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Story structure

An argument, on the other hand, logically leads the reader to accept a certain truth, based on a set of claims backed up by credible evidence. An effective argument arranges ideas into a hierarchical structure rooted in a single main idea. It presents a set of closely related claims, backed up by pieces of credible evidence, and all of this information works together to show why the main idea is true.

In a business plan, you must convince your reader to accept one core idea, that your business will succeed and repay the lender on their investment. It’s not enough for each concept and data point in your plan to relate to that idea, as in the loose structure of a narrative. Each bit of content in your plan must directly support and develop the core idea. The hierarchical structure of a business plan’s argument looks like the one in Figure 9.2:

Figure 9.2 Argument structure of a business plan

How to Build a Watertight Argument

To construct a persuasive argument, start by crafting short responses (one or two sentences, or a few bullet points) to the three key questions lenders want you to answer:

•What is the opportunity?

•Why is it significant?

•How will the business pay the bank back?

Then, based on your preliminary conversations with the lender, identify additional questions you need to answer within those three broad categories. (The more directly you can echo the phrasing the lender has used to pose those questions, the better.) Write short answers to each of those questions, and note the evidence you’ll use to back up your answer. That might include data from customer surveys or focus group, research into industry trends, case studies from companies similar to yours, and financial data your accountant has helped you prepare.

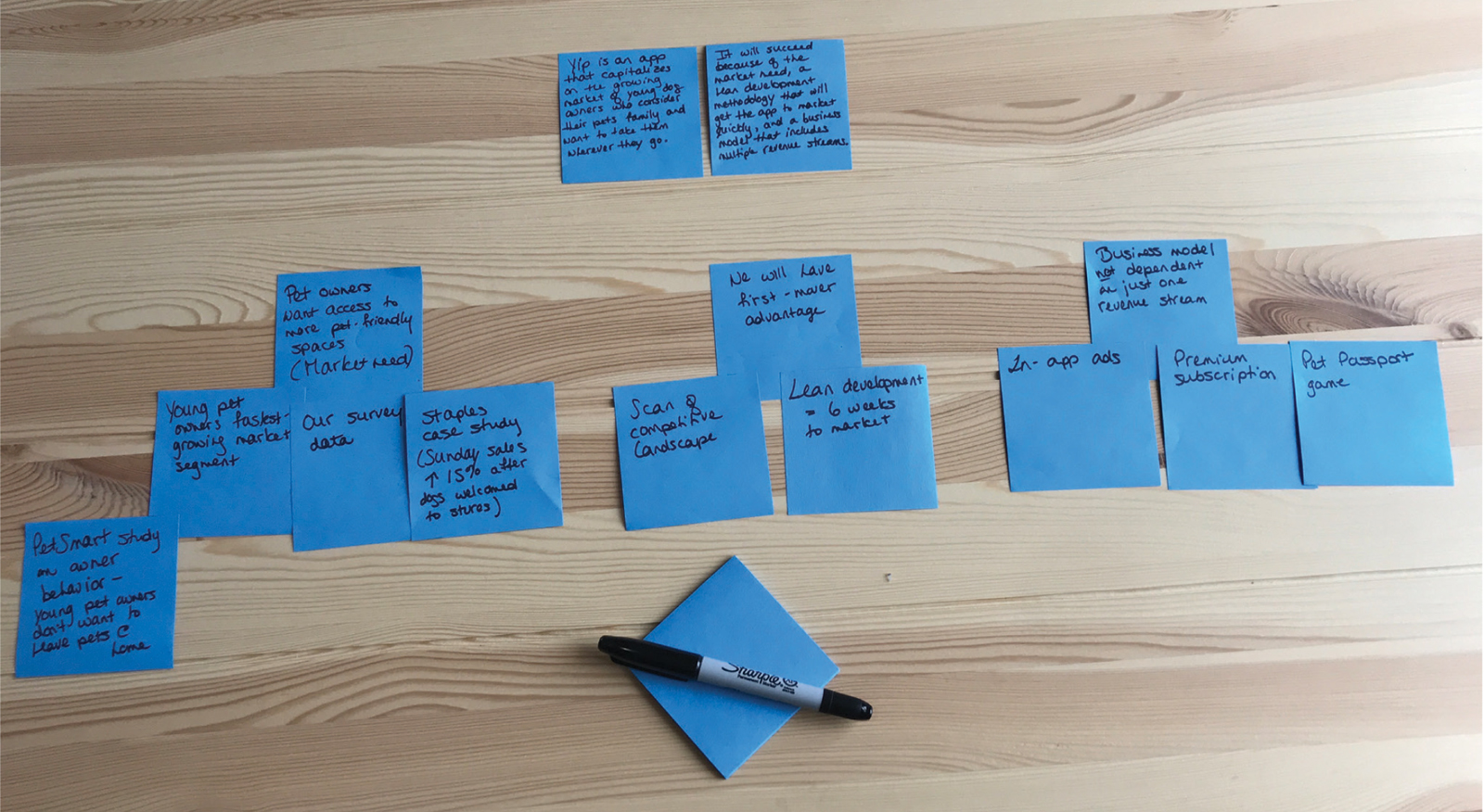

Now, you have the raw ingredients you need to start constructing an argument comprised of strong claims and credible evidence. Before you start writing, you might find it helpful to sketch a tree diagram similar to the example in Figure 9.3. I sometimes like to create a tree diagram from Post-it notes so that I can move claims and evidence around as I start to write.

Figure 9.3 Business plan tree diagram in progress

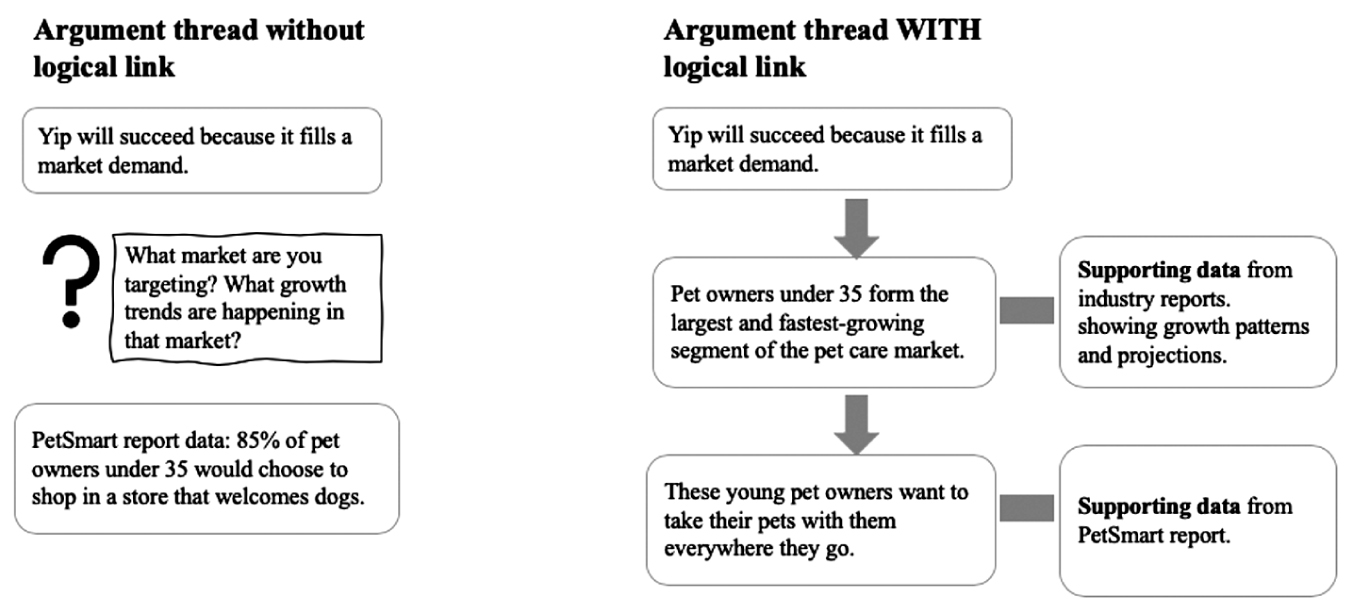

As you draft your argument, be sure to logically connect your evidence to your claims. You must make the logical linkages explicit because leaving it up to your reader to “connect the dots” leaves your document open to the risk of misinterpretation.

For instance, let’s say you’re developing a business plan for a new app called Yip, which enables dog owners to locate dog-friendly spaces (stores, restaurants, and recreational facilities) near them. One thread of your argument points out that pet owners in their 20s and 30s don’t want to leave their pets at home when they go shopping or enjoy time with friends. You have data from a recent PetSmart study confirming that 85 percent of dog owners under 35 would choose a dog-friendly store over a store that doesn’t allow pets.

This statistic could help support your claim that there’s a market need for your app—but only if you provide a link between the data from the PetSmart study and the market trend of a growing number of young dog owners who enjoy spending money as well as time on their pets. If you can show that young dog owners form the largest and fastest-growing segment of the pet care market, for instance, then the data from the PetSmart study appears relevant. Figure 9.4 shows how such market trend information creates a logical link between the claim that there’s a market need for Yip and the data documenting consumer behavior in the target market.

Figure 9.4 Logical link between a claim and supporting evidence

When presenting evidence to support your claims, practice viewing data sources through a skeptical lens. Be prepared to show why your sources are trustworthy and why their findings can be generalized. In the case of the PetSmart study, for example, you might want to mention how many stores and geographical areas it covered and what research methodology it used.

As with pitch decks, never assume that any kind of financial information you provide in a business plan, either in the body of the plan or in an appendix, can speak for itself. Take your reader by the hand and direct them to specific parts of your financial documentation that support your argument. In some cases, you might do that by providing a summary sentence or paragraph interpreting the financial data. In other cases, you might need to point the reader directly to a specific page or chart in your appendix.

As the business founder, you’re invested heart and soul in your venture, so it takes hard work to view it from an outside perspective. But the more skeptical a lens you can bring to your emerging plan, the stronger a case you’ll be able to make.

Think of this as a trouble-shooting exercise in two phases. In the first phase, your aim is to verify that you’ve provided just the right amount of detail to allow the lender to make a positive decision. In the second phase, your goal is to anticipate possible objections so you can rebut them within the plan.

1. Providing the Right Amount of Detail

In Chapter 7, I advised against falling into “tell-all syndrome,” the tendency to overwhelm the audience with information only tangentially relevant to the solution being offered. While this can be a hazard for business plan writers as well, a more common pitfall is to leave out critical information the lender needs to know in order to approve your funding request.

Table 9.1 lists the “standard” topics a traditional business plan covers. Depending on your situation, some of these topics will merit more attention than others. For instance, if you own a manufacturing business employing 40 people, then you may require a detailed operating plan. But if you run a three-person software development company, that section might be scant in your document.

Table 9.1 Traditional business plan topics

Build up the sections that give you the best leverage for persuading your audience. If your business is new, for example, don’t waste time trying to manufacture a detailed company history or overthink your financial forecast, which has no history to back up its assumptions. Instead, a more strategic approach would be to articulate a clear vision, demonstrate the market need, and play up your team’s strengths.

Feel free to shuffle the order of topics and change conventional labels to suit your circumstances. As you develop the relationship with your lender, ask them for input regarding the topics and arrangement of topics. Kyle stresses that banks are usually happy to work with a business owner and their accountant “in partnership” throughout the application process. If you’re wondering whether the outline you have in mind will enable you to hit all the points your lender is hoping to see, why not ask?

2. Anticipating Objections

To succeed as an entrepreneur, you must be a visionary and an optimist. But lenders are trained pessimists, so to convince them your vision is viable, you must train yourself to anticipate and deflect their negative reactions.

As you draft your business plan, picture yourself presenting it to a crowd of hecklers who are questioning each point you make. Imagine them shouting out three comments over and over again:

•How do you know that’s true?

•Where did you get that data from?

•So what?

Paying attention to those three heckler questions can help you anticipate the objections that will likely go through your lender’s head as they read your completed plan.

If your “product” is something intangible, such as a software application or a technology that you haven’t yet developed, then your business plan faces particular challenges. How do you convince pessimists of the value of something they can’t see or touch or of something that hasn’t even been invented?

Richard Howe works with Kyle at the CIBC as a manager of Commercial Banking specializing in the technology and innovation sector. He notices that many of the business plans he reads are “too descriptive and wishy-washy.” “They don’t drill down to what I want to see as a lender,” he explains. “There’s not enough substance.”

“Substance” for an investor means evidence that there’s market demand for what the business has to offer, solid financials, and proof that the intangible product will make a tangible impact. Let’s say you’re seeking funding for technology that enables a ship to navigate without disturbing marine life with sonar waves. The technology may function as an abstract concept in your lender’s mind, but here are some ways you could make it concrete for them:

•Show the market demand. Refer to the market size, industry trends (including environmental policies), and data that show customers in your target market are investing in eco-friendly equipment.

•Provide solid financials. Richard looks for a clear, compelling “numbers story” that shows how the business will make money and pay the bank back.

•Show the tangible impact. (Answer the question “So what?”) Describe how a ship’s crew uses the technology and the observable benefits it brings, such as improved efficiency (navigation is automated), reduced fuel consumption, and a competitive advantage over ships with conventional navigation systems.

Buzzwords won’t sway a lender, Richard warns. It takes hard data, especially detailed and realistic financial data, to make your business plan concrete and convincing. And don’t overlook “data” from your biography and the biographies of your team members. When you’re seeking funding for an innovative business idea that hasn’t yet been proven, demonstrating your team’s proven character can add significant weight to your argument.

Try This Instant Fix for Wordy Writing

A business plan is a “high-stakes document.” Because a lot is riding on it, you may find yourself laboring over its style, trying to make the writing sound more formal and impressive than the writing you produce for more routine documents, such as team e-mails. Be careful: when you try too hard to sound smart and sophisticated, you can cause your style to become impersonal and bloated.

To create a style that’s smart but trim, keep it personal. Rather than speaking about your company in the third person, use the more natural first person in its plural form. Rather than saying, “Blueberry was launched in October 2017 in response to a perceived market need for waterproof baby monitors,” try a more conversational approach, speaking in your own voice: “We launched Blueberry in October 2017 because we noticed more and more parents were hunting for waterproof baby monitors.”

See how much more energetic the second sentence sounds? It also sets up the development of the Blueberry as an intriguing story for you to develop. Where did you see parents “hunting” for next-generation monitors? How many of them were hunting? How desperate were they in their search?

As you concentrate on crafting a compelling written argument, remember that your business plan forms part of an ongoing conversation with the lender. The writing should sound like you (the smartest, most professional version of you) so that the way you present yourself in print continues to foster the rapport and trust you’ve been building in person.

Create a Compelling Executive Summary

In some ways, preparing a persuasive business plan is like playing a game. You must know and follow the official “rules”—the document form and format that make the most sense to the lender—and you must become skilled at anticipating and countering the other player’s blocking moves. Additionally, before the game can even begin, you need to pass an ordeal: the executive summary of your business plan must make it past the initial screening.

Your executive summary must grab the reader’s attention in just a few seconds. With just a glance, readers must be able to find the answers to their key questions and see that you’re supplying data to back up the claims you’re making.

Here are five tips to help you create an ultra-efficient, eye-catching summary:

1.Stick to no more than a page. That’s the absolute maximum. If the business plan is already brief, you may be able to get away with half a page.

2.State your main idea and your most compelling data up front. Information in your summary doesn’t need to appear in the same order as the information in your complete plan. Get straight to your boldest point and your juiciest evidence so your reader will want to keep reading.

3.Use headings and bullets. Design your summary for skimming, not reading. Keep your paragraphs short and break up content by inserting headings and using vertical lists.

4.Highlight key points. Strategically use bold type, text boxes, or underlining to call out critical information. Keep in mind that visual emphasis works only when it’s applied sparingly. If you use bold type more than two or three times on a page, it loses its impact.

5.Include numbers. To entice your reader to check out your financial appendices, give them a taste of what they’ll find there. Summarize your financial projections and the rationale behind them, providing a few key figures. A short chart may provide an efficient and eye-catching way to do this.

Sample One-page Business Plan

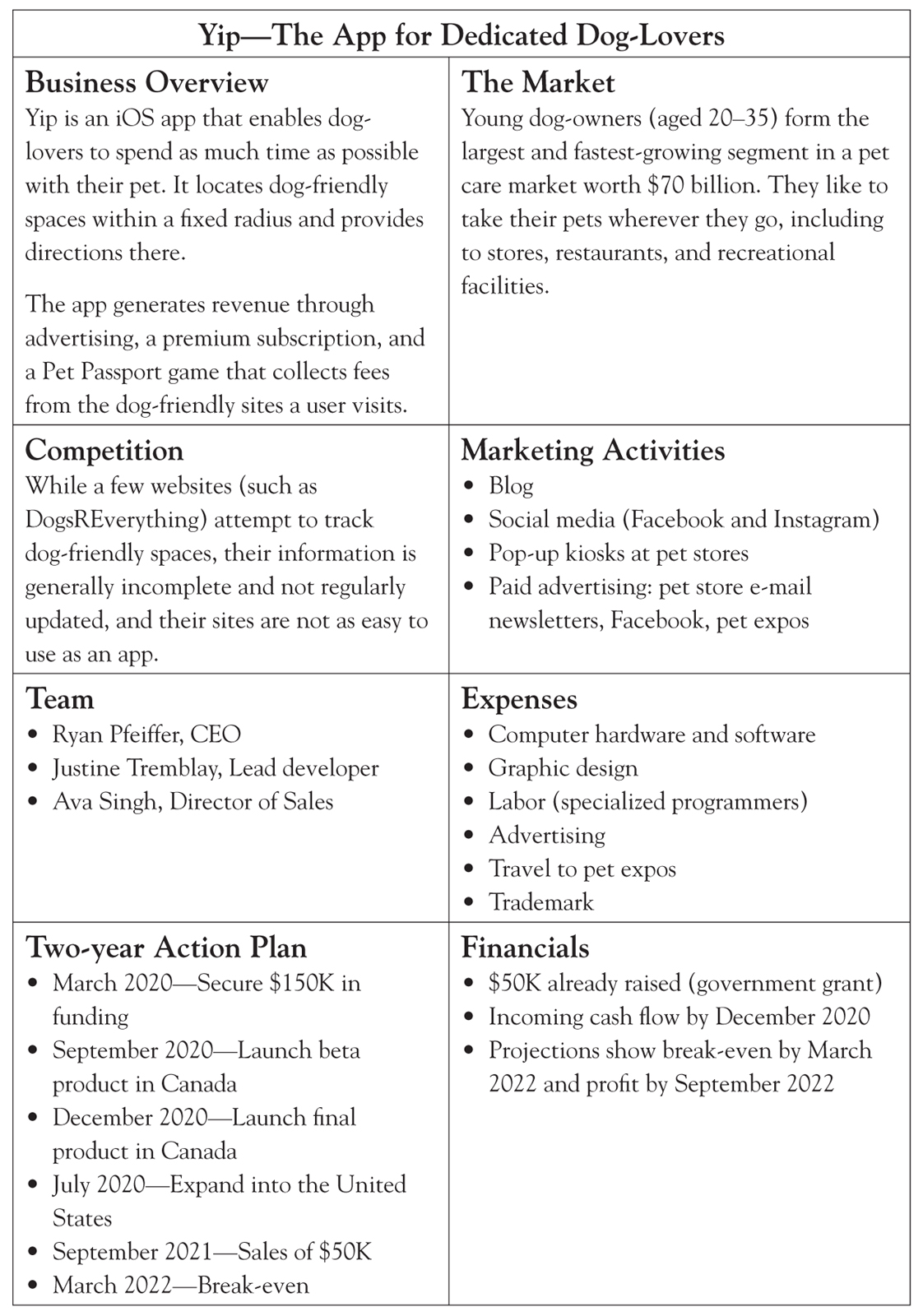

Lenders can differ widely in their preferred format for a business plan. A one-page plan like the one in Figure 9.5 could serve as a conversation starter in an early meeting, or it might serve as an attachment to an application form.

Figure 9.5 One-page business plan

This short document could also provide an outline for a longer document; it includes most of the major headings one would expect to see in a more conventional plan.

□Answers three key questions:

○What is the opportunity?

○Why is it significant?

○How will the business pay the lender back?

□Presents the business case as an argument, based on claims and supporting evidence

□Logically connects evidence (data) to claims (main ideas)

□Provides detailed financials, historical and projected

□Spells out the meaning of financial data

□Provides all the information the lender needs to make a positive decision

□Anticipates and deflects possible objections

○How do you know that’s true?

○Where did you get that data from?

○So what?

□Emphasizes tangible impact