When I think back on my first year as a university professor, I feel like sending an apology note to each student I taught. Or, rather, failed to teach. When I entered the classroom fresh from my dissertation research, I had deep insight into the inner workings of literature and culture but zero understanding of how to communicate those insights to other people. Especially undergraduates who had little interest in the fiction, poetry, and drama on the syllabus for English 101.

To make matters worse, as someone who’d always been a super-keen student, I couldn’t relate to my students’ lack of enthusiasm for the course of study I’d laid out. How could it be possible for someone to read Shakespeare or Faulkner and remain unmoved? Or to not even bother to read them in the first place?

As I started to recognize the breadth of the divide that separated me from my students, I became frustrated and discouraged. Classes started to feel like either pleas or stand-offs, with me trying desperately to attract student attention while defending the value of the course content. I felt like I was trying to communicate with aliens—and I’m guessing that my students probably thought I was also an alien speaking in a language completely foreign and irrelevant to them.

What a missed opportunity for all of us. With 20 years of teaching hindsight, I now realize that the gap between my students and me wasn’t the problem. That gap exists in all teaching situations because the goal of instruction is to create a bridge from ignorance to knowledge, from the territory of the novice to the territory of the expert. The real problem was my inability to view the course content through the eyes of the students and meet the learners where they were, not where I thought they should have been.

As a rookie professor, I didn’t know then what I understand now about how the brain works. Neurologically, the only way we can learn something new is to connect with something we already know, to build on or modify the existing neuronal networks that have formed through prior learning.1 When we’re teaching, our number-one job is to figure out how to make that link happen. That’s the secret to engaging learners, helping them remember what we’re teaching, and motivating them to apply what they’re learning to their personal circumstances.

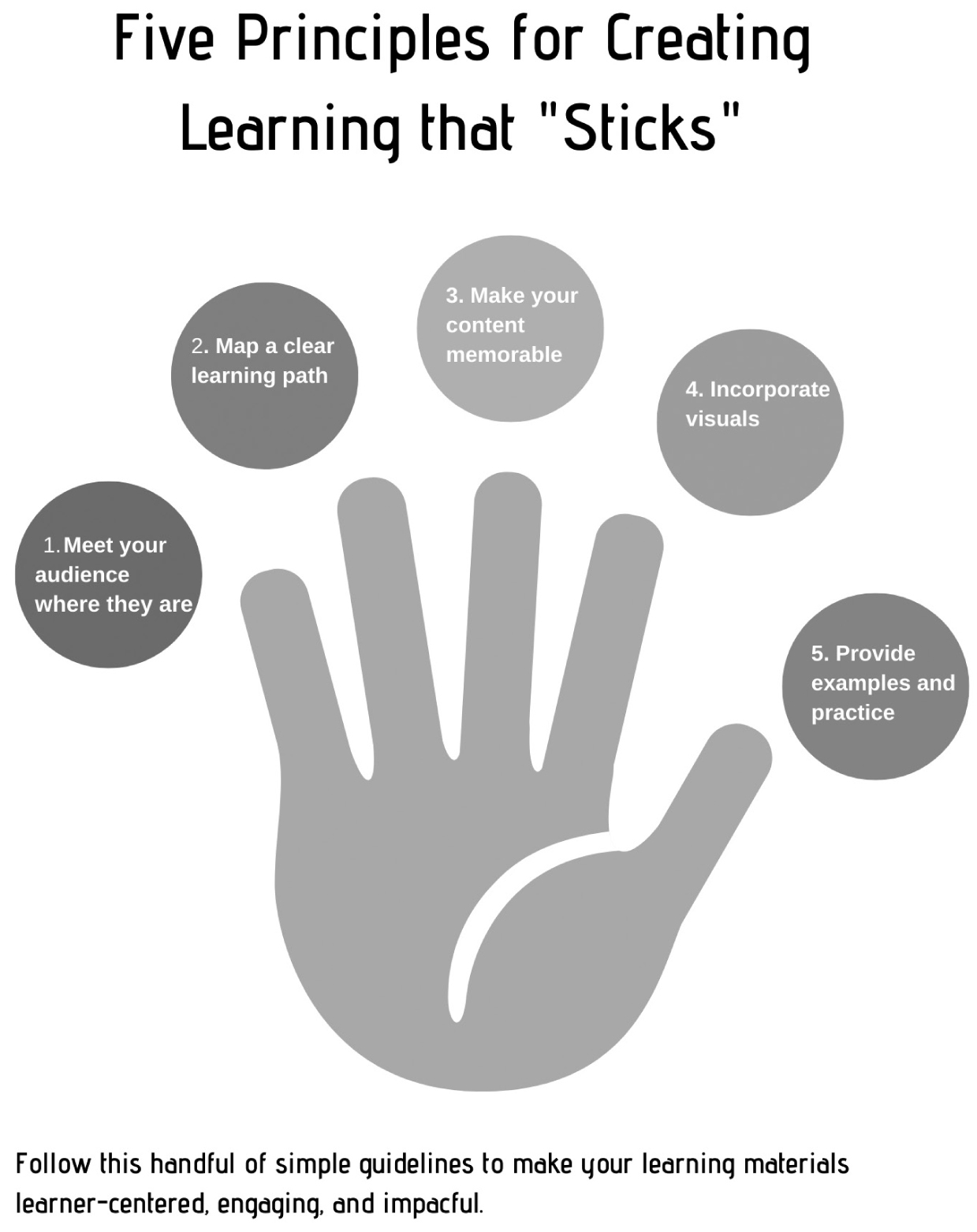

In this chapter, I’ll share with you five core principles you can use as you develop training materials to support your products and services. Those materials might include live workshops, instruction manuals, online courses, or video tutorials. Whatever form your “training” takes, the core principles will enable you to produce content that connects with your audience and turns them into raving fans of whatever product or service you’re teaching them about.

Principle 1: Meet Your Audience Where They Are

When you started your business, you probably had an ideal customer in mind. But how many of your current customers perfectly match that profile? As you’ve interacted with your market, you’ve probably had to adjust your preconceptions and adapt to the specific needs of the real customers in front of you.

When you design training materials, you may also start with an ideal learner, someone who’s interested in developing the knowledge and skills you have to teach and brings a certain level of knowledge and experience to the table. But it’s wise to check that profile against reality. Here are a few harsh truths you’ll need to face if you want to develop training materials that engage and help real readers:

•Most learners are rushed. Even learners who are interested in your topic probably don’t have the time they wish they had to explore it. Your readers want to be able to access key information quickly so they can quickly master the concepts and skills they need.

•Few people care about “theory” and “background.” As someone who’s created a complex product or service, you probably care deeply about its origins in theoretical principles or underlying technology. But people reading your training materials don’t want complex explanations; they’re looking for straightforward content that will help them perform real-world tasks. Save your background “theory” for conference presentations or white papers, and keep your focus on the practical.

•Learners don’t always show up with the knowledge you’d expect. I once taught a business writing course in Nigeria that was designed for people with advanced English proficiency and a university education. The real learners who showed up included professionals with master’s degrees from British and American universities as well as nomadic herdsmen whose formal education probably ended with elementary school. Although the diversity in that group may seem extreme, I’ve encountered an equally wide span of knowledge and experience in almost every group I’ve taught. Recognize that your training materials may need to teach people who lack some of the basics you might assume as a given.

•People need help “connecting the dots.” When I consult with clients as a learning designer, my chief task is to translate the knowledge of “subject matter experts,” or SMEs (pronounced smees), into content that novices can easily access and use. To do this, I ask a lot of questions, to the point that SMEs sometimes get a bit frustrated with me. Once they’ve shared their high-level perspective on the given topic, they tend to have little patience for walking through the details of how to pull practical insights from that knowledge and apply it in particular circumstances.

As the SME on your own products or services, you may share that impatience. But get over it. When you’re creating training materials, you can’t expect learners, who lack your expertise and experience, to intuitively make the leap from high-level concepts to hands-on practice. They need you to connect the dots for them through step-by-step instruction, examples, and practice opportunities.

•Many of us are scared to try new things. Despite everything positive psychology has taught us, I am frequently amazed by how many people underestimate the importance of cultivating a positive mindset among learners. True, some of us love learning for learning’s sake, but for most people, learning can be a daunting, even painful experience. Mastering new concepts and skills tends to mean hard work, and many of us feel clumsy and embarrassed as we try to do things we haven’t done before. Your readers need you to help them adopt a “can-do” attitude so they can approach learning with curiosity and confidence.

As you can see, developing training materials that work demands the same attention to your audience’s situation, emotions, and interests that you bring to bear on other kinds of writing. It’s a common mistake to consider training manuals, e-courses, tutorials, and other kinds of training materials as simple explanation. Keep in mind that many learners come to training materials feeling frustrated or intimated because they haven’t been able to figure out how to do something on their own. Many adults, in particular, also bring to a learning experience a lifetime of negative learning experiences, sometimes going back to childhood. Consequently, creating learning materials that engage learners and stick with them requires you to think about not just how to inform your audience but also how to motivate them to pay attention to the information you have to share.

Before you start to develop your training materials, then, take some time to learn as much as you can about your learners, not just who they are but also the specific pieces of knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes they carry with them. Below you’ll find few questions to guide you through that analysis so you can build your learning materials on the only solid ground available to you, the place where your audience is actually standing. You may find it helpful to complete the questions for various learner profiles (similar to the avatars for web writing you created in Chapter 4):

•What practical tasks do my learners want the training to help them perform?

•Why do they want to do those tasks?

•What knowledge about those tasks do my learners already have?

•What key pieces of knowledge or key skills are they missing?

•What related or similar kinds of tasks do the learners know how to do?

•What skills do they have that could form a foundation for skills they need to learn?

•How do my readers feel about learning the new task? What mental blocks might they be facing?

Principle 2: Map a Clear Learning Path (or Paths)

Analyzing your learners’ previous knowledge, as well as their attitudes and beliefs, enables you to map out the territory you’ll need to cover in order for them to master the knowledge and skills you’re teaching. The next challenge is to guide them along a learning path that’s easy for them to follow.

Our efficiency-loving brains thrive on structure, especially when it comes to learning new things. And they get pretty lazy about learning when there’s no structure to guide the various phases of recognizing, storing, and retrieving new information. As you develop your training materials, structure your content to make it as effortless as possible for your reader to proceed through the learning process.2

Here are some organizational tips to help you help your learners:

•Provide an overall description of the training. Let learners know the major goals they’ll achieve through the training, the topics the training will cover, and the format or method the learning will follow.

•List specific learning outcomes. Indicate the precise, practical takeaways learners will get from the training. An easy way to express these is to start with the following prompt: By the end of this training, you’ll be able to…

•Create a picture of the learning journey. As readers dive into your training materials, they’ll be wondering how long the learning journey will take, what supplies they’ll need to complete it, and how many stops there will be along the way. They’ll also be looking for shortcuts and ways to bend the learning path to their individual needs and preferences.

Depending on how diverse your anticipated audience is, you may want to provide multiple pathways through the training content. For instance, you might provide summaries of background modules so more experienced learners can skip over them. Or you might design content sections so learners can choose the order in which they read them.

•Break content into small sections. You might call these chapters, sections, modules, or steps. The label is irrelevant so long as you present the content in small, easy-to-digest bits that enable learners to feel they’re making steady progress.

•Use descriptive headings. Make your headings specific, and make them sizzle so that they grab learner attention. Descriptive headings also play a key role in helping learners preview and review section content.

•Summarize, summarize, summarize. Forming those new neuronal pathways requires repetition, so recap key ideas in strategic places. Normally, those include the end of a section, transitions from one main idea to the next within a section, and the beginning of a new section.

Principle 3: Make Your Content Memorable

Our brains work nonstop processing a steady deluge of sensory and cognitive data, and only a small proportion of that gets stored in our short-term memory. An even slimmer proportion gets transferred to our long-term memory and “embedded” there. How do you improve the odds that your training content will win the lottery for long-term storage? You generate emotional resonance, invent mnemonics, and incorporate visuals.

1. Generate Emotional Resonance

When we associate strong emotions with incoming data, we’re much more likely to embed that data in our long-term memory. You can generate emotional resonance by using feelings to frame your overall description of the training and your learning outcomes. What negative emotions does your audience feel now, without the knowledge and skills the training provides? What positive emotions will they feel once they’ve completed the training?

Stories also enable you to evoke strong emotions in your learners. Consider how you can weave stories into instruction and use scenarios for practice exercises.

2. Invent Mnemonics

Mnemonics are aids to memory, such as acronyms and rhymes. When we explored blogging in Chapter 6, you encountered an example of an acronym mnemonic, the PAVE method. The Finazz blog title I used as an example in that same chapter also created a mnemonic through rhyming: “Revenue is for vanity; profit is for sanity.”

Besides helping learners recall information, mnemonics enable you to brand key learning concepts or processes, giving you an advantage in the market.

3. “Chunk” Information Items into Groups of Five or Fewer

The jury is currently out regarding the maximum number of items the human brain can keep in short-term memory. For decades, Miller’s Law was thought to have decided the question. Research published by Harvard psychologist George Miller in 1956 found that the “magical number” for retention was “seven, plus or minus two.”3 However, more recent research has pointed out that a number of different variables affect the ability to recall discrete pieces of information and has proposed four as the new “magical number.”4

Insights from an Edutech Entrepreneur

Hussein Hallak is a serial entrepreneur whose latest product is CXO.ai, software that enables mentors to deliver curated content as e-mail courses personalized to the interests of their mentees. He also has an extensive training background, having taught marketing and entrepreneurship to a range of audiences, including members of Launch Academy, a tech incubator in Vancouver.

Hussein’s experience as an edutech entrepreneur and a trainer has given him some great insights into how to break down complex concepts into teachable bits. Here are a few of those:

•Read more. “Writing, for me, is a combination of reading and writing,” says Hussein. He reads widely, preferring books over web content because they “take a concept and break it down and go into it in depth.”

•Focus first. When developing training, Hussein doesn’t try to compress vast amounts of information into a single presentation or module. Instead, he zeroes in on what he calls “the core content” and builds from there. He recommends an organic approach: “Instead of thinking about what you want to say, think what you want to focus on, and the words will come.”

•Use groups of three. Hussein stresses that learners need a clear structure in order to process and absorb information. He loves breaking things down into three elements. “I love the number three. It helps people understand that it’s not an infinite thing that you need to do.”

Regardless of our alleged “learning style” or “learning preference,”5 of all the channels through which we receive information from the world around us, the visual channel produces the biggest impact on learning. The “pictorial superiority effect” ensures that “the more visual the input becomes, the more likely it is to be recognized—and recalled.”6

Whether or not you believe your target audience to be “visual learners,” incorporate elements of graphic design (such as text boxes, callouts, and icons) as well as visuals (such as charts, diagrams, infographics, line drawings, and photos) throughout your training materials.

Professionals who develop training materials call themselves “instructional designers,” not “instructional writers,” for good reason. When I consult with clients as an instructional designer, one of my chief tasks is to find creative ways to turn key teaching points into clear, compelling visuals. In many cases, the process of visualizing the content leads to a rethinking of the way that content is presented verbally. For example, let’s say we want to convey a set of 10 best practices for safeguarding cybersecurity. In order for us to communicate that information visually and in a way that’s simple to remember, the first step would be to narrow the list to three or four overarching best practices or themes, with each of those containing subpractices. With less than a handful of broad concepts to work with, we could then construct a visual “framework” (built of blocks or overlapping circles, perhaps) to help learners easily grasp and recall the content.

Figure 12.1 shows an example of a simple visual illustrating a set of learning concepts.

Figure 12.1 Example of a learning visual

Principle 4: Provide Examples and Practice

As noted earlier, many SMEs assume that learners will be able to “connect the dots” and link high-level concepts to real-world practice. If that were so, there’d be no need for you to develop training materials. You could simply rely on blog posts, journal articles, and white papers to develop the knowledge and skills your customers need.

Detailed, realistic examples and practice opportunities provide a bridge between the principles and ideas you’re communicating and the real tasks learners need to do. You may find, in fact, that you spend as much time producing examples and practice exercises as you do creating your core content. If you’re fortunate to be working with a team as you craft your training materials, you might consider engaging them in this part of the writing process.

As you develop practice exercises, consider ways to give learners feedback on their responses. Can you provide a model response, examples of different kinds of excellent responses, or an analysis of a typical response?

Principle 5: Create Tools for the Real World

The people reading your training materials are seeking practical information and skills they can use to achieve specific tasks. Well-designed training materials can take them only so far toward this goal. Ultimately, what they want and need are tools.

To complete your training content, provide user-friendly tools that make it easy for learners to apply what they’ve learned to their personal circumstances. Such tools might include worksheets, checklists, guidelines, pre-formatted spreadsheets, or short videos. Make these important training elements visually appealing, in compliance with your brand standards. Such tools also provide great opportunities to differentiate yourself in the market and to build up your brand identity.

Advice from a Neuroscientist-turned-trainer

Mandy Wintink has a PhD in psychology and neuroscience and teaches neuroscience classes at the University of Guelph. She also runs the Centre for Applied Neuroscience (CAN), based in Toronto. Through CAN, she teaches an integrated approach to life coaching that taps into her academic expertise as well as her training in yoga and meditation. Using this same holistic framework, she also delivers Brain Health and Wellness seminars for companies and public-sector organizations.

As Mandy moves among different learning audiences, she intentionally adapts. Practice, she says, makes it easier to flex your writing style as needed:

I have to be really conscious of my words. I have to really step out of myself; it’s changing my brain almost. I have to be very conscious of when I’m speaking in an academic voice and when I’m speaking in a general non-academic advice. I’m not talking the same way to every single person.

Mandy thinks of these different voices as different “hats” suitable to different situations. When she puts on her training hat (as opposed to her professor’s hat), she chooses simple terms and keeps her sentences short, aiming to write at about a Grade 8 level. As someone with deep knowledge of her subject, she doesn’t find this easy, but she’s learned to focus on the essentials and leave out “all the icing on the cake that I want to provide.”

Mandy also guards against offering too much theory and technical detail. “People say that they want to know neuroscience, but they don’t,” she explains. “They want to know a few things about the brain, but they don’t actually want to know how the brain fully works because when I go into that, it’s too deep for them, and they get lost.”

As CAN evolves, Mandy continues to experiment with different approaches to delivering instruction. For instance, she started out by offering participants in her life coaching program a user manual but soon found that a “static document” didn’t serve her learners well. Now, the program relies on a various of kinds of content, including videos and self-reflective exercises, to guide the learning experience. Such “multidimensional” content engages learners through different modalities, allows them to work at their own pace, and can be easily updated as the program continues to grow and change.

Checklist for Training Material

□Meets the audience where they are (not where you wish they were)

□Provides more practical information than theory and background

□Uses an empathetic, encouraging tone

□Maps a clear learning path by providing section overviews, headings, and summaries

□Makes content memorable:

○Generates emotional resonance

○Uses mnemonics

○Chunks information items into groups of five or fewer

○Incorporates visuals

□Includes tools for the real world

□Incorporates various kinds of content and, where possible, various forms of media

___________

1For a concise overview of the role of neuronal networks in learning, see R.J. Wlodkowski. Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn, 3rd ed. (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), pp. 8–13.

2Julie Dirksen’s book Design for How People Learn, 2nd ed., is chock-full of simple, straightforward advice for structuring learning materials to make them accessible and easy to remember (San Francisco, CA: New Riders, 2016).

3G. Miller. 1956. “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information,” Psychological Review 63, no. 2, pp. 81–97.

4N. Cowan. 2000. “The Magical Number 4 in Short-term Memory: A Reconsideration of Mental Storage Capacity,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 24, pp. 87–185.

5While the notion of a preferred learning style has become popular in K-12 education, post-secondary education, and the corporate world, there’s little empirical evidence to suggest that the concept holds any merit. Olga Khazan sums up some of the recent scholarly work making this point in her 2018 article for The Atlantic, “The Myth of ‘Learning Styles’” (April 2018). https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-myth-of-learning-styles, (accessed October 15, 2019).

6J. Medina. 2014. Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School, 2nd ed. (Seattle, WA: Pear Press), “Vision,” Kindle.