6

Is new content still king?

As with most things in life, entertainment was once a much less complex product, especially for television broadcasters. There were movies, a variety show, a quiz, the news, and a sports match. That was television. The accepted mantra, whether from Hollywood or Wembley, is still that ‘content is king’; if broadcasters package up the very best array of on-screen talent, then the audience will follow. Now in an age where the Internet and talk of interactivity and tele-shopping is seemingly on every broadcaster’s lips, the ‘content’ rule is getting a little frayed at the edges.

Content for broadcasting has traditionally come from a well-established number of sources, broadly conforming to the following categories:

- movie rights-holders (‘Hollywood’ and the other film studios)

- sports rights-holders

- mainstream broadcasters, who by means of generating original material (product) are creating fresh rights to be exploited

- thematic broadcasters

- programme producers, packagers and independents.

And more recently:

- narrowcast services

- data services.

The United States Federal Copyright Act of 1909 covered all published works in the USA, and provides the basis for the contracts of most studios. A major revision (Copyright Act of 1976) widens the scope of copyright to include unpublished works, and further refines the categories and scope of the earlier legislation to include (under section 102):

- literary works

- musical works, and their accompanying words

- dramatic works, and their accompanying music

- pantomimes and choreographic works

- pictorial, graphic and sculptural works

- motion pictures and other audiovisual works

- sound recordings.

There is no mention here of anything remotely connected to the Internet. But the narrowcast and data services mentioned above are generally seen as representing huge opportunities for broadcasters and those controlling the transmission pipes into people’s homes. These pipes, the so-called digital super-highways, are in the hands of broadcasters, cable companies and telephone operators. What sort of content traditionally goes down these pipes?

Movies are a primary driver for all subscription television platforms. In some markets (notably the Middle East and in particular Saudi Arabia), cinemas simply do not exist. In traditional markets, having the rights to broadcast the latest Hollywood blockbuster is very important to the television station. For the sake of brevity,the term ‘Hollywood’ here includes film studios wherever they may be based, but only where they conform to the Hollywood release pattern.

Some ten to fifteen years ago, the local channel or publicly-funded television network would broadcast a Hollywood film generally around three years after its theatrical appearance, perhaps holding back a special movie for Christmas, or another key date in the viewing year. There were no other choices available. The consumer either saw a movie in a cinema or waited three years for it to percolate down to television.

Now it is very different. Hollywood firmly controls the television market, and dictates when a movie is seen. The studios are bound by a set of customs and practices as regards restrictions on film release ‘windows’, and it is to Hollywood that one must look for an explanation on movie release patterns.

The key term involved in a discussion of release patterns is release ‘window’. A release window is that period of time when a licence is granted for commercial exploitation of the copyright. Some windows may be open-ended (such as theatrical or home video release), or highly restricted (subscription or pay-per-view television). For US-produced films, theatrical release is the first window, with a prompt follow-up for airline, video rental and PPV. The following list is a guide only, and many variations do occur.

Typical Release Window

| Month 1 | Cinema release |

| Month 3–6 | Airline release |

| Month 6 | Video/DVD rental |

| Month 6–9 | Pay Per View |

| Month 6–12 | DVD/Laser release for sell-through |

| Month 6–9 | Hotel Pay Systems |

| Month 9–18 | Video sell-through |

| Month 18 | Subscription TV |

| Month 18–36 | Network (free to air) TV |

| Thereafter | Syndication |

In general, Hollywood films are released according to a highly efficient plan, designed to maximize revenue for the studios. The studios’ goal is straightforward: to maximize the number of people who will pay to view the movie. Notice the key word here is ‘pay’. Simply releasing the latest Hollywood blockbuster after a few weeks in the cinema directly on to television would gain millions of viewers, but the revenue for the studio would be modest.

Hollywood maximizes the income prospects of a movie through the constant manipulation of the release windows in a continuous effort to maximize revenue in all markets. This means the length of the windows is frequently changing.

There are exceptions to this general rule. Commonly in North America and Europe there exist certain co-financing deals that may give the participant broadcaster certain release benefits, leaving the other partner(s) to gain corresponding benefits elsewhere in the world. For example, a broadcaster like Canal+ (which is obligated under national regulations to plough cash into French movie production) might jointly finance a movie with one of the large Hollywood studios. This deal would allow Canal+ to release the movie in French cinemas, and to show the film itself on its own channel after a reasonable interval, usually about 18 months. The ‘partner’ studio would be responsible for releasing the film in other non-French parts of the world.

These distribution deals might be quite separate from any profit-sharing agreements. Consequently, a broadcaster (like UK-based Channel 4) might financially benefit from a blockbuster movie like Four Weddings and a Funeral, although the broadcaster’s key aim in producing the movie was to attract viewers and therefore advertisers to the channel. The broadcaster also tries to balance the financial risk of investing during the initial development or production-financing stages, against the risk of paying far higher sums to acquire the broadcast rights once a film was a success.

The complexity is increased by other exceptions to the rule, including:

- US made-for-television films that might even be shown in cinemas in Europe (for example many Home Box Office(HBO) and other television movies are given theatrical release outside the USA)

- Hollywood films that box-office experience has demonstrated are so unappealing that they miss a cinema release, going instead straight to video

- made-for-television movies that miss video and go straight to subscription television.

Every player in the financial partnership required to get a movie made has its own vested interest to be considered, making some release patterns highly complex. This ‘controlled availability’, when combined with country-by-country distribution agreements and pre-sale commitments, will also help determine a film’s release pattern.

With the exception of movies that are heavily dependent on computer-generated graphics, digital technology is shortening the period from principal photography to cinema release, and this new phenomenon is altering quite dramatically the release patterns world-wide, especially for blockbuster movies. Until the mid-1990s, the key date in Europe that determined television screening was the release date of the video. Now subscription television plays a major role in this respect. Movies are generally available to be shown on subscription television (Sky’s movie channels, HBO, Canal+, Premiere, for example) 12 months after their video rental release, or some 18 months after cinema release.

The release pattern of Hollywood films is gradually standardizing, as Hollywood adopts a world-wide simultaneous release pattern. In the movie business, though, even a few weeks may carry a significant financial value. Releasing a film at the Cannes Film Festival in the spring is often enough to trigger the French video release date within a few months. Other film fans in Europe might still be waiting until the autumn for the movie even to be at the cinema, meaning a video rental the following spring. This pattern could mean a movie being shown on Canal+ six or twelve months sooner than on Sky, and well ahead of an Arab broadcast date, for instance.

Economic value

The early release of a Hollywood movie in the Dutch or Nordic markets is usually sufficient to guarantee a movie an early airing on one of the Scandinavian movie channels. The same applies in France with Canal+. There is another element in the equation, though, which is the economic or cash value of a country/market. In simple terms, it is the difference between, say, the UK and Germany, or Spain and the Middle East. The UK and Germany are simply more important markets for Hollywood films and will usually be higher on the list for distribution deals and release.

In addition to the normal movie ‘first window’ rights, other rights are classified linguistically. The ‘German-language rights’, which might cover the whole of Europe, would certainly include Austria and the German-speaking cantons of Switzerland (unless expressed otherwise).

Licensing and merchandising

Licensing and merchandising of products associated with movies and television series is today a highly profitable sector, and has led to some programming being marketed at less than its conventional value in a particular country or region because its exposure on television was expected to lead to higher revenues from ancillary rights. This is particularly true of some animation programming where the merchandising revenue potential from toys, foodstuffs, books and video sales far exceeds the income likely to be derived from a local broadcast.

Sports

Sports are generally recognized as a main driver of subscription television. The rights to broadcast a sporting event ‘live’ are again classified by market in much the same way the film rights are distributed. However, there is a significant difference in that ‘live’ sports events have a much greater value than recorded material. Spectrum Strategy Consulting, a London-based consultancy,stated in a 1996 report that live events tend to get some 30 per cent of the audience while a (first show) event recording will achieve less than 5 per cent of the audience. Consequently, significant sums are paid for sports rights to key events. Some significant examples include:

- In 1948, the BBC paid £1500 (equivalent to £27 000 in 1996 prices) for the rights to telecast the Olympic Games to UK viewers.

- In 1996, broadcasters from around the world paid a total of US$900 million for the rights to transmit the Atlanta Olympic Games.

- IN 1996, NBC, a US network, paid US$3.6 billion for the broadcast rights to the Olympics up to and including the 2008 Olympiad.

- In 1994, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation paid US$1.6 billion (outbidding CBS) for the television rights to cover four years of (American) National Football League. When, in 1998, the contract came up for renewal (for the 1999 and ongoing seasons) News Corporation paid a world record sum of US$17.6 billion to cover a seven-year period, or US$2.5 billion per season.

- In July 1996 Kirch Group, a Munich-based broadcasting conglomerate, paid US$2.36 billion for the rights to show the soccer World Cup competitions in 2002 and 2006. while Kirch has the exclusive rights for the competition, they will assign sub-leases of their rights to individual broadcasters around the globe. Indeed, it is quite probable they will make a profit from exploitation of those rights. Nevertheless, the sum paid represents a six-fold increase over the sums paid for the rights to the World Cup tournaments during 1990–98 (which achieved, in total, US$344 million).

- London Economics, a UK consultancy, stated in 1996 that sport accounts for around 15 per cent of all television spending. During its 1996 financial year, BSkyB spent some £100 million on sports – one third of its programming budget. The BBC typically spends 4 per cent of its programme budget on sports in non-Olympic years.

Table 6.1 shows other recent key sports deals of note.

Table 6.1 Sports broadcasting deals

| Event | Rights dates | Buyer | Cost |

| Olympic Games | 1996–2008 | NBC | $4 bn |

| Olympic Games (EBU) | 1996–2008 | EBU | $1.44 bn |

| World Cup soccer | 2002–2006 | Kirch | $2.36 bn |

| NCAA basketball | 1995–2002 | CBS | $1.73 bn |

| National Football League | 1995–1998 | Fox | $1.58 bn |

| National Football League | 1999–2006 | Fox | $17.6 bn |

| English Premier League | 1997–2001 | BSkyB | $0.96 bn |

| English Premier League | 2001–2004 | BSkyB | $1.65 bn |

Note: Cost in US$

In some cases sports broadcasters seem to have recognized the inherent value of by-passing the normal round of negotiations and instead are themselves acquiring ownership of the sport, or at least some of the key clubs. For example, Rupert Murdoch in early March 1998 totally acquired the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team for US$311 million (in other words, News Corporation owns 100 per cent of the club). Two weeks later News Corporation acquired a significant share (10 per cent for US$150 m) of the Los Angeles Lakers basketball club.

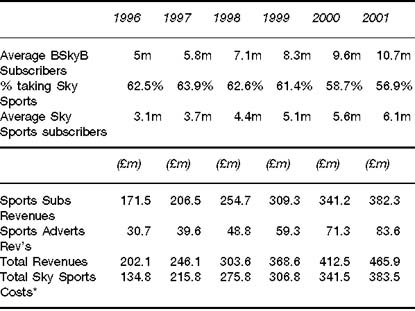

As a guide to the economic value of sports rights, it is worth looking at BSkyB’s cash-flow position, as examined by Dresdner Kleinwort Benson in August 1997, with regard to their sports coverage. The data stop at 2001 with the end of the current English Premier League soccer rights.

Other events

Some events lend themselves to special exploitation, in particular for pay-per-view (PPV) income. In the sports area this is especially true of boxing and wrestling, in particular in North America where boxing and wrestling bouts consistently do well. In the non-sports area concerts of popular music (and in North America country music events) and to a lesser extent of classical music

Table 6.2 Sky Sports Revenues, at June each year

*Includes Premier League costs

Source: Dresdner Kleinwort Benson

can also generate appeal. In 1997, events drawn from the list below counted for nearly 70 per cent of US PPV revenues.

- World championship boxing

- Wrestling

- Martial arts contests

- Pop-music concerts

- Classical music concerts.

UK-based boxing promoter, Frank Warren in June 1997 described championship boxing as:

the most honest form of TV, you cannot cheat the ratings, the figures are there to be seen, the revenues being split between the rights holders and [broadcasters]. Our first match (Bruno v Tyson) created a 14 per cent buy-rate (660 000 subs) even at5 a.m. ‘Judgement Night’ got 420 000 subs (9 per cent). The ‘Night of Champions’ 720 000 buys or 15.5 per cent and the ‘Brit Pack’ on May 3 [1997] achieved a 6 per cent buy rate largely because Tyson vs Holyfield was postponed.

Canal+ have been selling between eight and twelve channels of PPV soccer on their digital platform since 1996, although it has been reluctant to publicly announce the results to date. The attraction of PPV sports was perfectly described in 1997 by Swiss-based ISL, partners in the Leo Kirch deal to acquire television rights to the 2002/2006 World Cup tournament: ‘PPV is exciting, and is for the ultimate fan, the ultimate grass-roots supporter prepared to hand over some of his income to the TV turnstile, and the viewer who religiously enjoys every single split-second of the match. It also delivers some of the very best production values around.’

Charging PPV prices (usually at rates between US$10–50) for sports and event programming is simply exploiting the greatest value at the top of a multi-tiered pyramid of rights values, whose base is free-to-air television.

Mainstream free-to-air networks

It is part of broadcasting folklore and often repeated that in the early days of video-recording, some public broadcasters struggling to meet budgetary constraints wiped the video recordings of their programmes to re-use the tape in order to save money on buying new tape stock. They thereby destroyed any prospects for the original item to be shown again.

Such an action would now be seen as wilful destruction of the broadcaster’s main asset: the content. Today’s public and commercial mainstream broadcasters are as shrewd as the Hollywood studios in exploiting and re-showing their material. They invest in new programming with two objectives. The first, naturally, is to satisfy their viewing audiences. The second is to allow them to re-broadcast the material or sell on the rights in the form of licensed windows to other broadcasters, either in the originating country or in foreign markets.

A network might originate its own show and repeat the transmission later that week or some time later. It might air the programme on a subsidiary network that it owns, or sell the rights to a rival station once the unique merit of the show has faded. It might also sell the show overseas.

The USA is the most aggressive seller of its broadcasting content, arguably proving to generation after generation of viewers that its output is the most popular on the planet. Whether it is in shows like Wagon Train (1957–65), Peyton Place (1964–9), Dallas (1978–91) or Baywatch (1989 to date), the world’s television stations have bought US television shows above all other productions. It is arguable as to the real merits of some content, but the ‘typical’ viewer loves them.

However, the USA has also had to operate under some very strange regulations. The US terrestrial networks operate under Federal Communications Commission (FCC) restrictions as to the number of broadcast hours they may produce for their own transmissions. These regulations (or licence obligations) were strengthened in 1971 by the Prime Time Access Rules (PTAR), which limit network affiliates in the top 50 (USA) markets to three hours of network programming from their own production resources.

The FCC rule was intended ‘to make available for competition among existing and potential program producers, both at the local and national levels, an arena of more adequate competition for the custom and favour of broadcasters and advertisers’ (FCC, 1971). The result of the ruling was to open up the 7–8 p.m. EST time block (and post-11 p.m. time slot) for non-network producers to gain access to the network.

The rule was allied to the 1972 introduction of the Financial Interest and Syndication Ruling (‘fin-syn’) designed to limit the financial involvement of the main networks in the programming produced for them. The networks were restricted from wholly owning the show purchased or commissioned by them. While a network’s main objective was always to secure what it saw as top programming for its audiences, the result, prior to the fin-syn act,was to limit severely what the originating producer could subsequently do with the show once its main network showing was completed.

The fin-syn rules, although significantly eased in 1991, had the result of creating a strong independent production sector in North America. Most of the cinema studios set up television divisions, first to work with the networks but then to exploit the syndication, overseas and other re-transmission rights permitted them under the ruling. The main networks also sold off their own production divisions: CBS sold its division to an emerging company called Viacom and ABC sold its production to Worldvision.

Those regulations have now been relaxed, but as an example of the complexities involved, the 1996–8 US television ratings-winning programme Seinfeld is produced by Time Warner-owned Castle Rock Television studios. The show is ‘first run’ contracted to the NBC network, although it is offered for sale by Columbia TriStar Television Distribution for the syndication market.

Outside the USA, the television value chain has evolved more conventionally, with public-service broadcasters taking the lead in national production. Even the entry of commercially funded broadcasting has not altered this picture; the commercial stations (though more likely buyers of material imported from the USA) have still heavily invested in studios and original programming, initially for their own use but increasingly for overseas sale.

Thematic or niche broadcasters

Thematic broadcasting differs from mainstream broadcast programming in that it focuses on niche or special interest material, with the explicit intention of attracting viewers to that niche. Channels devoted wholly to movies and sport are examples of thematic channels. Movie channels, by and large, are acquirers of existing product, and while some US movie channels (in particular HBO) invest considerable sums in producing or commissioning new films (for television showing in the USA), the majority of film channels do little more than provide interstitial programming links between movies.

However, even within the generic ‘movie’ classification, there are now channels themed into sub-classifications: action, romance, comedy, for example. One such themed movie channel, American Movie Classics, owned by Rainbow Media Holdings, in May 1998 launched ‘American Pop’, showing archive films, newsreels, promotional films designed to ‘tap into popular culture’. While the use of ‘classic’ and ‘cult’ material may not create original (and thereby newly licensable) programming, in many cases the channel brand itself becomes a valuable asset. Cartoon Network is a perfect example of this, with the checkerboard logo licensed in many countries.

The Disney Channel, which mixes animation with live action programming, launched ‘Toon Disney’ in early 1998, a self-contained digital channel designed to appeal to younger viewers. This is also fast becoming a licensable device.

C-SPAN, an analogue and digital television service in the USA, which broadcasts ‘gavel to gavel’ coverage of the House of Representatives (and C-Span 2 which covers the Senate chamber) launched in March 1998 a new audio channel, C-Span Radio, as part of a digital audio bouquet offered by CDRadio, a 50-channel direct-to-car satellite service scheduled for launch over North America in 1999. The radio service demonstrates that extra revenues can be achieved from lateral spin-off services, where core material can be re-used to create income and reach wider audiences.

There are growing numbers of thematic channels available as part of subscription television bouquets which increasingly create their own exploitable programming copyrights:

- Discovery, a documentary channel founded in 1988, originally bought in all its material from existing film and video libraries, drawing heavily on the archives of public broadcasters around the world, not least the BBC. Today it is the leading commissioner of documentary programming in the world. In March 1998, it entered into various joint-ventures with the BBC to co-produce and finance new channels. The first three channels, Animal Planet, People &Arts and BBC America, have proved remarkably popular, and others are planned.

- Arts & Entertainment (A&E), a thematic channel owned in part by the US network NBC, has spun off another channel, The History Channel, devoted to factual documentary programming. One of its constituent parts, a nightly Biography programme is also under consideration to be spun off as a stand-alone channel. A&E has followed the Discovery example, and while initially only exploiting existing archive material, is now increasingly involved in commissioning new material specifically for the channel.

- The BBC, through its commercial arm BBC World-wide, has entered into a joint-venture with Flextech plc, a company owned in part by Tele-Communications Inc. to launch new factual thematic channels under the UKTV brand (Horizons, Arena, Style etc.). Initially, the channels will exploit the BBC library, but the agreement is already leading to the origination of ‘new’ programming for the channels as well as new versions of existing programming, for instance, a 50 minute version of a 30-minute motoring programme Top Gear.

- Canal+ has invested (along with TCI, Havas and other companies) in ‘Multithematiques’, a group of documentary channels (Seasons, Jimmy, Cine Cinema, Planete etc.) which are being rolled out to other European platforms in which Canal+ has an interest. Multithematiques is committed to increase local production, especially for its Seasons channels (described as a thematic channel for those interested in hunting, shooting and fishing).

- CNN, perhaps the best known of all niche broadcasters, launched its all-news network in June 1980. Since then, it has launched sub-niche versions of the channel: CNN Headline News, CNN International, CNN fn (Financial News), CNN:SI (Sports Illustrated), CNN Airport Network and CNN Interactive, plus stand-alone services for Latin America, and is a 49 per cent share-holder in ntv, a German-language news channel. Moreover, the CNN brand is now seen on language-specific local news channels (CNN+ in Spain, CNN-Turk in Turkey) and more of these are planned.

- Cartoon Network, created by Ted Turner but now owned by Time Warner, initially depended on its vast library of MGM cartoons, but some five years ago realized that to keep the library growing it had to invest in new programming. As a result of that decision, new animated programming has been commissioned, including material from European creative houses (which has helped overcome some of the regulatory quota problems within Europe), and such new programmes have been among the most popular shows aired on the channel.

Some other better-known American thematic channels include:

- Black Entertainment Television (BET)

- Playboy TV

- Nickelodeon

- ESPN

- Disney Channel

- E! Entertainment TV

- Family Channel

- Lifetime

- Nashville Network.

All of these channels are investing in new programming, so that they own at least some of the broadcast as well as ancillary rights.

Producers and packagers

The role of programme producers who create programming for the main broadcasters has already been examined. There are numerous other producers who are less well known, even though their shows may be very familiar. A good example is Carsey Werner Inc., who currently ‘handle’ shows such as The Cosby Show, Grace Under Fire and Third Rock From the Sun.

Often it is difficult to differentiate between programme producers and channel or programme providers. For example, does Hallmark Entertainment Network qualify as a studio? It produces‘made-for-TV movies’ of the calibre of Gulliver’s Travels and Moby Dick, which it sells to mainstream broadcasters around the world. However, Hallmark also packages product for its own channels around the world, especially for those regions where its own product is not available (because rights have been assigned to other broadcasters).

The same analysis could be applied to a channel like National Geographic Television which, when launched in 1997, reportedly owned only some 180 hours of its own exclusive material, not all of which was exploitable in certain key markets (again because rights had been assigned elsewhere). Consequently, it had to acquire and package suitable natural history and similar documentary material to show under its brand. National Geographic Television also works with Canal+ and Turner Original Productions in DocStar, the packager (with Explore International) of the trio’s documentary programming.

Discovery Communications is clearly a major producer (and co-producer) of factual programming. It has also entered into joint venture, co-production deals to make new programming with organizations such as the BBC, Canal+, German public broadcaster ZDF and others. It licenses its product to other broadcasters, but also has to acquire programming from third-party producers for some of its own spin-off channels, such as The Learning Channel (TLC, also known as Discovery Home & Leisure in some regions of the world) and newly announced channels like Discovery Kids and Discovery Civilisations. In some cases Discovery will act as a packager of third-party produced programming for certain of its channels, especially where its own archive is not complete enough to provide sufficient high-quality material to sustain a channel.

Discovery is also moving into radio, packaging a weekly audio service (from May 1998) in a joint venture with a division of London-based Television Corporation. The service is designed to offer ‘half-a-dozen topics per program,’ according to the company, which will mirror Discovery’s usual video content.

Narrowcast television

Digital television presents a much greater opportunity for highly specific narrowcast services. For example, Canal Satellite Numerique is already transmitting:

- Medicine Plus, a closed-circuit channel for doctors

- Demain! (Tomorrow), a ‘self-improvement’ channel

- France Courses, a horse-racing channel

- f. Fashion TV (a fashion channel, and see below).

Other tightly-targeted thematic channels include: CNN’s group of sub-niche news channels (CNN Headline News, CNNI, CNNfn, ntv etc.); Bloomberg Television, a spin-off of Michael Bloomberg’s stock-exchange data service; and NBC’s global news channel CNBC, also designed to serve business-viewers.

Narrowcasting can be even more finely tuned than these sub-niche examples. For example, f.Fashion TV is a Paris-based, thematic channel broadcasting in digital from EUTELSAT and Astra, but it has announced the following narrowcast services:

- f-1, the current channel comprising advertising-free, non-stop catwalk show video-clips with the original backing music, featuring more than 100 of the world’s leading couture houses;

- f-2 will broadcast interviews with the designers, backstage scenes and advertising;

- f-3 will be a PPV channel, broadcasting full fashion shows;

- f-4 is described as comprising programmes for ‘fashion-conscious viewers’;

- f-5 is a shopping channel.

Proposed extensions to this package include f-g, a proposed ‘gay’ channel, f-s for sports-wear, and f-j a ‘jeans and junior’ channel. These channels could not possibly be financially viable without the transmission savings brought about by digital television.

Elsewhere there are broadcasters using digital television to narrowcast educational services. Sheikh Saleh Kamel, the SaudiArabian television entrepreneur, has launched one channel devoted to students of the Koran. India, Pakistan and China have variously announced plans to adopt digital television for distance learning projects. Within Europe, Denmark has been using digital television for many years to transmit educational and other programming to isolated communities in Greenland.

Satellite operators, SES/Astra, EUTELSAT, Orion, Galaxy and PanAmSat have all spoken of plans to encourage narrowcast services to businesses. Some companies already have Very Small Aperture Terminal (V-SAT ) installations (closed circuit transmissions) often in analogue, but increasingly switching to digital transmission, for moving image and data services to clients. A good example in Europe is the Ford Motor Company, which uses such services to talk to dealers.

Data services

However large and unexploited the digital business television market may be, the adoption of digital data-transmission services by the likes of DirecPC, Canal+ and others cannot be ignored. Chapter 10 covers the PC/TV convergence in some detail, including data transmission direct-to-home and to small office/home office users.

Business Television (BTV) can include moving image transmission as well as data. SES/Astra have formed a joint venture with Swiss-based The Fantastic Corporation to offer data services across greater Europe with minimum infrastructure investment. The Fantastic Corporation, claims the value of this sector to be worth US$400 billion a year. The company uses Astra’s high-power transmissions to broadcast data to small dishes (about 60 cm diameter, depending on location). The small dishes and inexpensive digital decoder boxes have dramatically reduced the overall installation costs for such multiple installations. SES/Fantastic launched the service in early 1998, and are already supplying digital bandwidth to customers (which, they state, include many ‘Fortune 500’ companies) for the following applications:

- corporate announcements

- internal company communications

- distance learning programmes

- in-store customer viewing.

Almost without exception, satellite-transmission owners can offer similar services. Astra has its own proprietary data-casting system (Astra-Net) which launched in January 2000 (although it had some 50 clients already using Astra-Net by the end of 1999).

There are many companies offering similar services globally. In the USA, Convergent Media Systems (CMS) claims to serve 70 per cent of the business television market, initially in analogue, but rapidly switching to digital transmission. CMS estimates it delivers programming to more than 40 000 offices totalling some 5 million people in the private sector. It also serves 17 000 higher education schools with upwards of 10 million students. In government (local, state and federal) it claims to supply data services and video material to over 1000 locations serving more than 1 million people.

Walt Disney World, the Florida theme park, uses Business TV datacast services from satellite company Globecast North America to transmit and receive between the Disney/MGM studios (located at Disney World) and the Disney-owned ABC broadcast studios in Los Angeles and New York. In addition to having the ability to send and receive material, the circuits will also be used to transmit a 24-hour radio show for Disney (Radio Disney, ABC’s 24-hour music programme).

Flextech – moving into interactivity

Flextech has now merged with Telewest and what is increasingly clear is Flextech’s adoption of interactivity as a revenue-generating tool for its broadcast channel, as well as web-based access. As a case study, their entry into on-screen e-commerce is a near perfect example.

Adam Singer, Flextech’s chairman (as at December 1999) is keen to see the end of analogue broadcasting, but also hints that Flextech’s analogue service could be curtailed well before satellite subscriber numbers are down to the last 200 000 or 300 000 homes. ‘It takes a lot of subs to pay a £4.5 million per annum transponder cost. This has not been thought of and it may be that the cut-off point on satellite is much higher than had previously been imagined and it’s going to be interesting to see what happens.’

Setting aside the conversion to digital, Flextech’s progress during 1999 was good. Its ad-revenues grew 30 per cent against market growth averages of 20 per cent. Its UKTV joint venture saw revenues boosted 52.9 per cent to £34.4 m, with flagship channel UK Gold’s operating profits up 66.5 per cent to £9.1 million. Out went the loss-making Playboy TV (sold in March 1999) and in came a 25 per cent stake in Multimap, which provides online maps and guides.

Flextech’s thrust is towards interactivity on most of its channels. In 1999 Singer said ‘Our interactive division in the last six months made, excluding the travel side, £387 000 in ad revenue. That’s starting from zero. We are staggered and delighted. I can tell you that is more ad revenue than some full channels are making in a full year – not Flextech channels I must stress – although it’s more than the advertising revenue we took on some of our channels when they started up a few years ago. So clearly there is a lot of money out there and this, we believe, is a true indication of what is available from advertising without touching the e-commerce income possibilities. Look at Living Health where you have the channel together with drop-down diagnostic opportunities plus e-commerce and you have a whole range of advertising benefits.’

Flextech is looking to sell its Living/Bravo/Trouble channel formats into overseas markets, but Singer says the current priority is the Internet and interactivity. ‘Part of the issue is that the Internet wave has hit all of us in television. We are the new kids on the block, and we had better find that fountain of youth.’

Of course, everyone is searching for the golden prize at the end of the broadcasting rainbow. Open … the digital interactive servicefrom BSkyB, BT, bankers HSBC and Panasonic, started its transmissions in basic form in mid-1998, with extra services added throughout 1999. During 1999 around £60 million was spent on advertising and promotion. Open…’s CEO is James Ackerman.

Open…’s technical director Colin McQuade said in 1999 that the Open… system was not like the Internet. ‘It’s designed for TV. It’s designed for my mother who has never seen an error message on her TV set, or had to re-boot whenever she wants to watch the news.’

Referring to the spectacular growth of Dixons’ Freeserve free-of-charge e-mail service, which very quickly racked up more than 1 million subscribers, McQuade predicted ‘This time next year [that is in early 2000] Open … will be the biggest e-mail provider in the UK’. Sky digital subscribers will be able to send and receive e-mail anywhere in the world. Up to eight e-mail ‘accounts’ can be dedicated to each subscriber, allowing parents and children, for example, to each have a dedicated e-mail address.

‘E-mail is going to be phenomenally important’ said Open…’s chief executive James Ackerman. ‘E-mail provides traffic, traffic means more people will come into the Mall and create more opportunities to transact.’ Users will also be able to pick up e-mail at their office, or via BT’s High Street interactive terminals. ‘It would be a disaster if it were just limited to fellow subscribers to Open….’ Sky is selling a wireless keyboard, styled to match the remote control, costing £39, although Ackerman also expects the device to be given away by some retailers as a branded premium.

Open … added Hasbro as a retail partner who will use the Sky digi-box to download games to consoles. Ackerman said the technology was now in place to download any other commercial software direct to the PC, linked to the digi-box. Open … launched with 68 Mbps of satellite capacity (from Astra 2A, equivalent to about two transponders) and more is available as the system grows, says Ackerman. ‘Then we’ll start to learn. We’ll see whether books sell better than CDs or CDs sell better than trainers and we’ll start making some decisions as to which products our consumers want.’

‘I know Sky is not putting any less emphasis on this venture,’ said Ackerman. ‘In fact they are putting more emphasis through the creation of their own interactive division. Sky One, Sky Movies, Sky Sports and the rest will all have brands developing interactive elements. Flextech have done the same with their interactive division so that we can start developing applications ahead of the game, beating a lot of people to the punch. It is absolute nonsense to suggest that Sky is emphasizing this venture any less. Further to that, one of the main differentiating factors between analogue and digital TV is interactivity, and interactivity is Open …. You will see this year a lot of emphasis from Sky Digital on interactivity on the Open … services. What people have had up till now is emphasis on the launch of Sky Digital and the broadcast services because that’s all there was.’

He argued that the Internet has developed portal sites to bring order from chaos. ‘An interactive platform like Open … is bringing things together, quality retail sites to the most commonly used device in the home, the TV set. No need to enter web addresses, no need to go through complex routes and the ability to promote your products through the broadcast stream. This has got to have a massive interest. I believe the Internet proves that the interest will be there and that this is going to take off big time.’

Datacasting: the PricewaterhouseCoopers view

In December 1999, management consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), released a major report on what they called ‘datacasting’, the broadcast transmission of data, which is worth examining in some detail. According to PwC specialist Howard J. Postley, datacasting has been around for over 15 years. In many cases, data are incorporated alongside other media for ‘free’ transmission; for example, using the vertical blanking interval (VBI) in a television broadcast.

This is especially true in Europe, where the VBI portion of the analogue signal has been used for, among other things, so-called ‘teletext’ services. In addition to these text services, though, the VBI has also been used by broadcasters to ‘piggy-back’ other content, notably specialized slow-scan data and picture files forclients. In the UK, for example, British Rail uses the VBI on an analogue satellite channel to ‘broadcast’ its train timetables direct to its platform television displays.

The USA (in its analogue transmissions) uses the VBI not for messaging or teletext but for ‘closed captioning’ of broadcasts for deaf and visually impaired viewers.

Whether or not they are bundled with other signals, datacasts are frequently secondary content in support of primary broadcast content, as services like the Radio Data System (RDS) illustrate. Regardless of how the signals are transmitted, or with what other media they may be associated, datacasts usually consist of text-only information.

PwC’s Postley stresses that ‘mediacasting’ is an altogether different concept. While mediacasts may include some of the same types of data, they go far beyond datacasts. Mediacasting is the broadcast delivery of rich-media content directly to storage in addressable receivers. Unlike traditional broadcasts, mediacast content is designed to be stored at the destination before it is presented.

PwC expect that mediacasting will not only supplant data-casting, it will effectively replace broadcasting as it is currently performed.

Market forces

Postley says that mediacasting is the result of a variety of forces but is, at the core, one of the many ways in which that convergence is changing the broadcasting industry. There have been many debates about whether broadcasting will be replaced by the Internet, whether all Internet content will be provided by television programmers, whether all Internet use will eventually be through television, and so on. These discussions, while interesting insofar as they serve to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various media, are largely irrelevant.

PwC recognize that the single most significant force to shape mediacasting is the internet, and its standard yet flexiblefoundation. By breaking media and other data into small digital chunks, they can be moved over any kind of transport link, from a slow dial-up modem to a fast fibre-optic connection or wirelessly via terrestrial and satellite broadcasts. In fact, all of those mechanisms can be used in different parts of the route. Like shipping a package, the shipper does not care how a package gets to the destination, and the freight company does not care what is in the package.

The basis for all digital transmission is the breaking up of data and/or images into digital chunks, or packets. These packets can travel not only over a variety of transport media, but also they can travel different routes, depending on a variety of factors, and arrive in a different order from when they started – to be reordered back into the correct sequence at their destination.

The Internet, says Postley, allows the use of receiver processing power to reduce transport inefficiencies. While it is easy to discount the use of the Internet and its associated technologies for the delivery of media to the home, it is important to recognize the value that the flexible Internet protocols provide. As an example, PwC uses the delivery of a single US television signal. An analogue television channel in the USA uses 6 MHz of spectrum for 30 minutes to send 30 minutes of audio and video content. There is no practical way for time or bandwidth to be reduced while retaining compatibility with common receivers. In the digital world, the equivalent content can be transferred in approximately 1.25 MHz of spectrum for the same 30 minutes. While the amount of spectrum is reduced due to digital coding, current technology receivers are still designed to deliver and play the content in ‘real time’; i.e. it is played as soon as it is delivered.

PwC accurately state that the evolving model for mediacasts is fundamentally different. Since mediacasts are designed to be stored at their destination before presentation, other options become available. A half-hour SDTV (a digital channel but of conventional, that is, non-HDTV format) programme requires approximately 720 Mb, (that is 30 minutes × 24 Mb/minute = 720 Mb) of disk if it is to be stored.

Unlike standard broadcasting, mediacasting allows burst delivery. Using a different kind of compression that benefits from having all of the content stored before it is decompressed, the 720 Mb can easily be reduced to less than 90 Mb. By mediacasting that content as data using all of a standard SDTV channel (that is, a standard higher-definition, but not HDTV, digital channel in the USA), 30 minutes of content could be delivered in well under one minute. To look at it another way, an entire day of television programming could be delivered in less than 45 minutes. The ratio of compression for countries outside the USA is slightly different, but the argument is just as valid.

New formats mean new opportunities

PwC say datacasting enables the role of the receiving devices to change into that of intelligent network peripherals. This, in turn, enables a dramatic increase in the variety of those peripherals and the diversity of media that they can use. There are already a number of peripherals which use mediacasting to create new opportunities, and others which do not currently utilize mediacasting but are clearly headed in that direction. An example that is easily recognizable is the new digital video recorders (DVR) now being offered by entrepreneurial companies such as TiVO and Replay Networks. While technically these devices are a new form of the traditional VCR for standard broadcasts, it is useful to look at them as mediacast receivers where the mediacast happens to be carried in the format of a standard television signal. It is not difficult to envisage similar devices receiving content that has been burst over cable or satellite, or trickled in through a DSL connection.

At least two US companies, Tranz-Send Broadcasting Network and Intertainer, are now attempting to establish themselves for video distribution using this method. Because mediacast content is played from local storage, it makes no difference how long or what route that content took to get to the receiver.

Additionally, says PwC, one should also look past the traditional television set, because there are a variety of new devicesbecoming available which also must be supplied with media content. Today, electronic books, such as the Rocket eBook and SoftBook, and digital music players such as the Diamond Rio and Saehan MPMan, are supplied on an individual basis via the world wide web. Likewise, the computer software industry is rapidly moving to electronic distribution. Video games, especially those that require some type of network connectivity for multiplayer gaming, are likely to follow this lead.

New viewing model

Mediacasting will support a new viewing model that allows the consumer to do the content aggregation. Traditionally, content is selected and scheduled for passive viewing by the networks or cable providers. The majority of consumers want a relatively small subset of the available content. We already see that large numbers of consumers have identical content delivered to them individually. Imagine if every song on the radio had to be delivered separately to each listener every time it was played. Current delivery mechanisms are much more expensive than they need to be. This situation is exacerbated by the ever-increasing costs and complexities associated with serving a growing audience.

An addressable broadcast solution, with receiver storage for an ‘on-demand’ capability, provides a much more efficient and scalable solution. Given that the DVRs are already shipping with enough storage to store more than a full day’s worth of continuous viewing, and the ability to schedule its playout, and the availability of new types of media devices coupled with the capability of mediacast burst delivery, every broadcaster has to ask the question: ‘What is the highest value use we can get from our bandwidth inventory?’ Given the opportunities presented by these new technologies, ‘commercial television’ is not the only answer and, increasingly, may not be the most profitable.

Jockeying for position

PwC says the industry, and consumers are looking forward to a digital future, but there are a very few paths to get content toa destination. Historically, right-of-way issues have limited options for telephone and cable TV service providers. Ironically, similar types of issues are likely to limit wireless options from satellite, microwave and RF sources in the same ways. While the businesses of the companies that provide them continue to change, the primary ways of getting significant amounts of data to a destination will continue to be cable, telephone lines, broadcast RF and satellite. However, while the delivery channels may not change much, the ways in which they are used will change dramatically. Today, less than 25 per cent of the US population receives television solely ‘off-air.’ By the time the current FCC-mandated date for digital television cut-off in the USA rolls around, that number will be less than 10 per cent. The question is: will there be anyone watching a DTT signal?

As is evident from its penetration into US households, cable is the preferred channel for media delivery. There are myriad reasons for this but one of them is the sheer capacity. A digital cable system can provide up to 1 GHz of bandwidth, as much as 4 Gbps of data. Contrast that with the just under 20 Mbps of data that can be provided by a DTT channel or the puny 1.5 Mbps of ADSL and the advantage is clear. However, that advantage is also temporary. Estimates are that within five years, the average American household will receive 5 Gbps of data. For that to happen, given the estimates for digital cable roll-out, the majority of that bandwidth will have to be delivered via wireless means. While wireless broadcast systems lack cable’s return path, telephone companies are already positioning themselves to solve that problem. A 1.5 Mbps inbound data channel may be nearly useless for media delivery; it is more than adequate as a private dedicated outbound channel.

Implications

PwC point out that in 1989, Nicholas Negroponte, Director of the MIT Media Lab, predicted what has come to be known as the ‘Negroponte Switch’. He predicted that most forms of communication that had been carried on wires would move to wireless means and those that had been transported wirelessly would moveto wired services. Due to the inherent complexities and costs of providing high-bandwidth via widespread deployment of any type of wiring, several effects appear likely.

- The majority of inbound data to consumers will arrive via wireless means.

- The majority of outbound data from consumers will depart via wired means.

- Transport mechanisms will be combined to provide the most optimal configuration for a given application.

- Internet Protocol (IP) will provide the common ground to allow bifurcation of inbound and outbound communication channels and the replacement of one-source solutions with open systems.

PwC define the ‘broadcast crossover’ axiom as their corollary to the ‘Negroponte Switch’. This axiom states that the majority of media that have historically been presented under the control of the broadcasters, at the time they are transmitted, will be mediacast and presented under the control of the audience at times it finds convenient.

These changes present a variety of new business opportunities for broadcasters and many other businesses in the broadcast industry. While the growth of bandwidths to each home would tend to imply that bandwidths will become ‘commoditized’, limitations on available spectrum will continue to make broadcasting a business of resource management. Furthermore, the development of new devices and new types of media, coupled with the continual increase in the quantity of traditional broadcast media, will more than counterbalance the increased data density that can be achieved through improved coding and modulation techniques. For a variety of reasons, broadcasters have been limited to a specific media type for a given facility – television facilities do not transmit radio. While their essential asset has always been their ability to transmit any type of content, the facilities are optimized for a single type. Changes in the marketplace, however, will cause a re-evaluation of past practices. Mediacasting can allow broadcasters to become more focused on deriving the mostvalue from their bandwidth and less on the content it carries. A mediacast of television, music, and interactive media require the same facilities.

A by-product of mediacasting and the ‘broadcast crossover’ axiom is that processes that have been implicit in the broadcast product can now be made into products of their own. For instance, the optimization of a broadcast schedule in order best to satisfy the target audience is a complex task. Mediacasting will enable schedules themselves to become content of their own and, due to the transactional nature of mediacasting, revenue generating products. This is exactly what TiVO is attempting to do; their hardware enables the sale of their scheduling service.

PwC say that since all mediacast content goes to storage before it is played out, users perceive that it is available on-demand. That demand can be generated directly by viewers, by schedules, by other content and any combination thereof. The same set of content can support everything from a mass-audience schedule to one for an individual viewer. Furthermore, the different sets of advertising spots can be inserted depending on the schedule. While these capabilities have been described in terms of television programmes, they also apply to music, video games, books, and any other content that can be mediacast.

New devices, new types of media and new services mean new types of customers for mediacasters and also new responsibilities. With the increased diversity of the content and its audience, mediacasters will need to cultivate that same kind of diversity in its sales force to approach and service a much broader range of customers and customer needs. The range of opportunities is likely to be so large that the most critical business issues will be those related to choosing and servicing the subset of opportunities that are most promising and put the mediacaster in the best strategic and competitive position.

Mediacasting will consolidate a variety of technologies into a system that will ultimately replace traditional broadcasting. Broadcasters are among the best positioned to take advantage of the new system. To the extent that the bandwidth is available, itis more efficient and more scalable to broadcast content and allow the decision to store it to be made at the receiver than to address data to individual receivers at the transmitter. However, adoption will require new business models, reformulation of corporate and operational strategies, new processes and new systems. The combination of more bandwidth and addressable receivers with local storage allows one-to-many broadcasts to behave like one-to-one narrowcasts. Broadcasters can apply traffic yield management and focused audience targeting to achieve zero marginal cost per receiver.

PricewaterhouseCoopers state simply that mediacasting will change the face of broadcasting and that broadcasters must adapt to remain competitive. They are right. Dr Abe Peled heads up News Data Systems, the News Corporation-owned company that develops broadcasting technologies, encryption and compression systems. Peled is also acknowledged as one of the industry’s foremost thinkers. In January 2000, he described his views on television’s digital future. Peled says:

The biggest factor, I call it the sleeper of technology, is the growth in local storage. When the PC first came out, in the early 1980s, it came with 10 Mb of local storage. Today you would be hard pressed to find anything with less than 2 Gb of storage. That’s an improvement factor of 200 times. The modem at that time was about 2400 bps, today the equivalent would be a 28.8 Kbps, another significant growth factor.

As the prospects for a 10 Gb hard drive becomes interesting, when it is linked to compression and inserted into an STB it can expand the content window. In the UK the content window before Channel 5 and Sky was four, a four channel content window. With cable and Sky analogue, you have a 40 channel content window, more in the USA, perhaps 80 channels. With digital the content window expands to nearer 200. Today’s improved compression could give us 400 channels of content without a problem. But if you add 10 Gb into the STB now, costing around $100 in the year 2000, that would addanother 50–80 virtual channels. But go just a little further, and add 100 Gb of hard drive would mean 800 virtual channels. And 100 Gb is suggested for within the next 5 years. So we think the biggest revolution as far as the consumer is concerned will be local storage, which will completely change the paradigm for viewers, which is currently based on time. We ask ‘what’s on now’. And local storage changes that, and we can start asking ‘what would I like to watch’. It is going to be content-driven from your local disk, with maybe 1000 hours of choice, and not necessarily the 200 hours of broadcast channel choice.

Peled predicts viewers will dramatically change not so much what they view but how it is called up for viewing.

You can come home and view Friends or Eastenders, whether it is on the air or not. Because it will be a content-based paradigm, not a time-based paradigm. Programme schedulers get paid a lot of money to package together an interesting evening of material. They will vanish. And advertisers will need to look again, perhaps even paying us to view their ads. They will either have to be very entertaining or give us a reward, perhaps a prize, for watching them.

Asked whether these developments will change the way programming has traditionally been viewed, Peled is unequivocal.

The reason people want to watch TV is because they like to chat about it the next day around the coffee machine or watercooler. And that is true, and big events, sports, news stories, and other key programming will still attract viewers. But the fact is that in the USA some 40 per cent of viewers don’t bother to watch these big events. They tune away. My answer is ‘yes’, there will be a some boring people who want to talk about last night’s big event. And my TV friends say they are still in the majority. But there will be another group of people who might see it an hour later, or the next day, or the following week. They want the content, not the time.

We began this chapter talking about content, and finished with much the same phrases. Content is king, and will always be king, whether it be a transmitted movie or a web-streamed movie that has been downloaded to our set-top box overnight. However, the concept of sitting down at 8 p.m. in the evening to view a network’s prime content is fast dying. We might want to see the show at 7.45 p.m, or 8.15 p.m. – and we will get it. We might want it the next day, or the following week. The broadcaster will give it to us, or else they will go out of business. Whether movie, or news broadcast, or datacast or Internet access, the rule remains that content – in whatever form – is still king.

There is another theory which suggests that broadcasters might have to find another model to attract us to their key programmes. This is one that gets down to the fundamentals of what commercial television is all about: money. It may be that the network will start to pay viewers directly for watching the prime-time 8 p.m. show. They might not actually send us a cheque for what might be a very small amount of cash, but it’s quite likely that they’ll tempt us with prizes, or money-off coupons, or some other sort of reward that’s directly linked to our viewing.