by Judy Armstrong and Steven Zoppi

Having departed the practitioner's role (for a while) and joined the ranks of IT industry analysts, I discovered an interesting and unexpected demand on my time. I began receiving calls from CIOs whose careers were in jeopardy because their team's value (and by association, their value) had been brought into question by the other business leaders. After about an hour of forensic dialog about how this situation evolved, I was alarmed to conclude that there was an emerging epidemic of highly effective organizations and leaders whose value had been completely overlooked because of the lack of problems. They had been waylaid by the perception that “Everything works, so you guys must not be doing anything,” swiftly followed by the “What have you done for me lately?” yardstick. While I concede that I am slightly oversimplifying the circumstances, the reality of the situation was that those worried CIOs had actually done something wrong—they hadn't properly marketed their products to their internal customers. Their reward for a silently efficient and low-defect operation: a negative perception of their effort and productivity.

In this chapter Judy Armstrong and Steven Zoppi discuss:

• How the IT marketing effort is related to communication, quality, consistency, and high interaction.

• The importance of managing expectations.

• Models for planning a marketing campaign.

• PEST and SWOT analyses.

• The importance of business value chains and IT value chains, and how they are related.

This chapter serves as a sourcebook of ideas in marketing your organization's strengths and weaknesses. There are no “silver bullets,” and not all of the concepts presented here will be appropriate for all organizations, but the ideas should be sufficiently illustrated to enable you to apply them to your challenges.

One of the basic challenges to all marketers is understanding the problem. In the Dilbert comic strip by Scott Adams, the “pointy-haired manager” interrupts the title character with the following monologue:

(Pointy-haired manager): I put together a timeline for your project. I started by reasoning that anything I don't understand is easy. Phase One: Design a Web architecture for our worldwide operations. Time: 6 minutes.

(Dilbert, copyright 2003 United Feature Syndicate, Inc. All rights reserved. Used with permission.)

While this is a cartoon, it is not beyond reality to expect this type of thinking, which appears ridiculous but often occurs. When was the last time you called your local telephone service provider and thanked them for bringing you dial tone? When was the last time you called your local power company to thank them for keeping your lights on? When was the last time your department was credited for consistently delivering more value for less money, regardless of how the rate of consumption increases?

It is highly likely that your own customers, no matter how closely you work with them, have become habituated to the services provided and have no understanding of the complexity involved in their delivery. Assumptions give rise to incorrect or undesired conclusions.

The marketing effort is not a function merely of communication but of quality, consistency, and high interaction with key players. As an element of communication, a game plan for all interaction must be carefully crafted to ensure continued matching of expectation and business need.

In this chapter we explore how IT issues form the backdrop of key topics that a good marketing plan will address. There is a considerable amount of synergy to be derived from key business relationships, and all types of out-of-synch conditions (with the business needs) can be mitigated by a sound marketing and communication strategy.

There are a multitude of options the CIO can take. Doing nothing is a certain path to failure, so it's important to understand the effects of not marketing IT. We also attempt to derive a clear definition of what marketing entails (or does not) as it relates directly to IT. Through the application of good marketing practices and the local application of some general examples, the intent is to help establish reasonable results with a minimum of discipline and effort.

Another perceived issue, formerly believed to have considerable effect on the marketing plan but of decreasing value today, is this: Does the IT team serve a constituency that is largely technical or nontechnical? The relevance of the technological sophistication of the customer base is diminishing due to the ubiquity of technology in business life. With this ubiquity comes a breed of Monday-morning quarterbacks who, while conversant in commonplace technology, are woefully lacking in the complexities and challenges of current corporate information technology. This presents a special marketing challenge.

Information technology, while arguably one of the most important infrastructure elements in a corporate operating backbone, is also one of the most underpublicized, undermarketed, and misunderstood components of any corporation. There are two primary contributors to this lack of understanding. The first is a complete misinterpretation of the maxim “The customer is always right.” The second is that marketing, in the form necessary to connect with the customer, is just plain difficult and is viewed as an inconsequential luxury by most IT organizations, which are already under constant pressure to perform with declining funding and often contradictory business directives.

For purposes of this chapter, we need to define IT marketing:

IT marketing is the art of appropriately setting expectations between customer and service provider such that both entities enjoy a mutually beneficial economic relationship.

This definition may appear to contain the grand presumption that IT professionals all understand their respective roles within the organization. But many marketing problems, by their very nature, stem from the history of those agents of change, the IT professionals themselves. In today's state of the art, most IT professionals have come through the ranks of IT and not through the business. This exacerbates the situation by putting all the emphasis on being a reactive rather than business-driven organization.

The marketing action is, by definition, an overt and proactive step toward establishing appropriate levels of service delivery and expectation within all layers of the organization. Generally, the customers of IT organizations perceive them as high-cost, low-quality service providers. This is largely due to IT groups' unsuccessful attempts or complete inability to articulate service value. But IT groups demonstrating cost competitiveness and service differentiation can construct IT value chain models to diagnose their deficiencies, improve their images, identify new cost reduction opportunities, link to vendors' value chains, and build key differentiators.

To begin, there are a multitude of great Web-based and text resources for developing a marketing plan. Because the IT product is targeted primarily at an internal audience, many of the steps are abbreviated. The key steps are outlined here.

There are two key activities that focus the development of the external plan: the PEST analysis and the SWOT analysis. These two concepts are widely used, and there is a plethora of information about them available on the Internet and in texts to help the team make the appropriate assessments, so a quick overview should suffice.

PEST stands for political, economic, social, and technology factors. These are all elements that may have an effect on your future business or on that of your company, division, or operating unit. In this analysis, the objective is to make a list of all factors that may be either beneficial or detrimental to overall success in either the business or the marketing campaign. All of the PEST factors tie into and may have an effect on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats you identify for your product and market.

SWOT stands for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, and is critical to any well-crafted marketing plan. By completing the review of your business and your market, you should be in good shape and armed with the information needed to identify SWOTs and PESTs.

Strengths and weaknesses are determined by internal elements, while opportunities and threats are dictated by external forces. Sometimes it is more helpful to identify opportunities and threats (OTs) first in order to more quickly bring to light the product strengths or weaknesses of highest priority.

Executive Summary: An internal management summary of IT's marketing plan.

The Challenge: A brief description of your services and business objectives to be marketed along with associated goals, such as high-level budgetary constraints, in-process work, and strategic goals.

Situation Analysis: A brief analysis of the organization, the company's context around the organization, and the challenges (financial, product, or other matters) to which IT can bring specific benefit.

Customer Analysis: A somewhat more rigorous analysis of the number of organizations you support, the number of different functions they perform and value drivers they might have for the IT organization, how their decision processes work, and how they operate.

Competitor Analysis: For IT, the competitive analysis is more of an introspective assessment of where core and non-core competencies lay. In this analysis, it is important for the CIO to carefully choose battles. “Outsource non-core competencies” is the background mantra here. Understanding of SWOT and PEST will make this analysis flow more easily and prepare the CIO for the real tests of strength. Outsourcing is not always a competitor, but it can be if it's not initiated conscientiously and with the coordination of internal IT.

Collaborators: In any campaign, it is always important to know who the allies are. These include vendors, internal customers, advocates, technology evangelists, and any other business unit members who have a keen understanding of the IT challenge. They are the business “operatives.”

Market Segmentation: At this point, there is enough information to determine how to segment the internal marketplace and “choose those battles wisely.” The principle of Occam's Razor is an excellent guide when choosing the low-hanging fruit for any marketing plan. The most useful statement of this principle for technologists is:

When there are two competing theories, which make exactly the same predictions, the one that is simpler is the better option.

So, choose your first audience wisely (on the basis of the best mutually beneficial economic relationships) with a clear understanding of the problems they face (in terms they understand) and what is of the greatest benefit. Identify the messages that most resonate with them, and how the IT organization can best support their objectives. Identify their sensitivities to cost, time, and other challenges.

Alternative Marketing Strategies: List and discuss the alternatives that were considered before arriving at the recommended strategy. Alternatives might include discontinuing a service, repositioning an existing one, or identifying the key benefits the IT organization brings to the company table.

Selected Marketing Strategy: Explain why the final strategy was selected. Finally, identify the marketing mix decision about the four Ps of product, price, place (distribution), and promotion.

Measure the Results and Project the Outcomes: This section of the marketing plan identifies the selected strategy's immediate effects as well as the expected long-term results and any special actions required to achieve them. This section may include forecasts of expense, potential revenues, ROI, and possibly a break-even analysis.

Conclusions: A succinct summary of all of the above.

Assessing an IT department's current value chain from the following scenarios (see Figure 14-1) and applying the recommended strategy can help form a successful marketing plan:

We can dispel the misinterpretations of the maxim “The customer is always right” if we suspend our belief that marketing is a luxury. In fact, where a sound marketing plan is laid out, the customer can always be supported properly and therefore be “right.” This plan becomes a cornerstone in supporting an appropriately scaled IT and business response plan.

Marketing must be a core competency of the organization and must be addressed to successfully help the customer be always right and therefore satisfied. IT analyst organizations have spent person-years crafting the right catch phrases to accurately describe the issues, results, and remedies for IT problems. IT organizations themselves spend almost no time at all in crafting the right message for their respective target audiences.

Neither the customer nor IT department members are presumed to be psychic. Many goods and services, no matter how beneficial or innovative, have remained in obscurity due to a lack of presence in the consumer consciousness. Many inferior products (VHS video format) eclipse their superior competitor (BETA) due to excellent marketing campaigns. No matter how technologically sophisticated and superior the services provided, the disastrous results of considering marketing a luxury cannot be overstated.

Undermarketing IT usually results in many or all of the following:

• Low morale in the IT organization.

• Silos of excellence.

• Armchair quarterbacking from the customer community in general.

• Fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD); customer dissatisfaction.

• Lack of customer ownership and sponsorship of their own products.

• The blame game.

All department members must be enlisted as part of the marketing force for the remaining techniques to be effective. There are amazing stories about how one incorrectly applied message can undo all of the goodwill generated through a carefully planned campaign. The reinforcement of these key messages through an appropriate rewards and recognition program sets the stage for the remaining techniques.

Because of the serious nature of these changes, to IT's company profile, executive sponsorship is compulsory. For those organizations choosing to use an IT advisory board, the members of the board should be apprised, involved, and encouraged to become advocates in establishing and supporting the appropriate feedback required by their respective organizations. For organizations that do not have those types of business ties, the key managers' performance plans need to include that advocacy role for which they must also be compensated through incentives tied to its fulfillment.

In every sound marketing campaign, the needs of the consumer are identified through market analysis. The internal campaign can more easily harvest information about the needs of the market through systematic analysis of the business requirements. In the process, additional information can be discovered about the various disconnects between customer perception and those of IT.

Once the business requirements have been fully analyzed, key performance indicators (KPIs) should be cooperatively identified by the business and IT groups. These KPIs should then be iteratively refined to form the foundation of routine communication. This implies that requirements (not simply “wants”) must be carefully culled from discussions with business unit representatives (either business analysts or key business contacts) who act in an analyst capacity. These requirements become the basis of service level agreements (SLAs). From that point, the KPIs become the foundation for harvesting metrics relevant to the business, including:

• Routine and substantial reporting of successes in terms that are understood by the widest possible constituency.

• Appropriate benchmarking inside and outside of the IT organization.

• Establishment of clear and well-focused objectives.

• Correction of the vocabulary at large within the IT organization (group-think).

One of the greatest contributors to the poor marketing of IT is a culture of “anti-service” within the organization. An example of group-think gone bad is found in the casual use of the word policy throughout most IT service organizations. Individual contributors frequently use the word policy in saying “It's not our policy to do that” as a defense against ad hoc requests for services.

Unfortunately, unpublicized policies used in this manner can generate the opposite effect. Without understanding the reasons for policy, the capriciously applied term can result in undoing the spirit of a carefully crafted marketing plan. Customers assume that the IT organization is a hopeless bureaucracy and look for ways to work around the IT organization. While policy is an extremely important part of the IT discipline, volatile, numerous, complex, and ad hoc policies can completely undermine the intent of an effective IT organization. Effective policies (as discussed in other chapters in this book) must serve as marketing tools and vehicles, and as such must meet the following marketing criteria:

• They must serve a specific business need, goal or objective.

• They must be well written and specific, yet generic enough to promote infrequent modification. (If frequent change is necessary, this may be a “standard,” not a policy.)

• They must be concise so they can be easily memorized.

• While it is important that policies contain the rules and the consequences of breaking those rules, they must also be fully enforceable and universally applicable. Policies that fail this test, these latter tests are “guidelines” and should never be used as policies.

• They must never be statements of current best practice or anything else that is truly a guideline.

• Effective policies (whether internal or external) must be well-publicized, internally and externally.

Effectively communicating success can be an important operations morale booster both inside the IT organization and for the customer communities. Early wins and internal “reference customers” can be highly effective models in the pursuit of other, less cooperative constituencies.

External benchmarking information (for example, what other services are provided by comparable IT organizations with comparable user communities) is helpful but can be misleading. Statistics regarding spending rates in particular are a poor marketing tool, since these benchmarks are often the results of custom-crafted accounting practices, and surveys regarding spending should always be considered suspect unless their foundational data can be correlated. Benchmarks regarding staffing and support expressed in ratio form are seldom beneficial for external marketing, because they detract from the objective of having negotiated KPIs drive the results stated in the marketing campaign.

In short, while statistics can be highly useful, they can also be misleading and create an uncomfortable position to defend in an institutionalized manner. It is everyone's experience that goods and services can be “sold” using clever marketing practices, but our recommendation is to garner and retain customer and executive sponsorship by using credible claims and estimates.

To best achieve the goals of the marketing activity, it is imperative that we understand the two basic rules governing circumstances under which the customers always right:

• Rule 1: The customer is always right if, and only if, the claim to being “right” is limited to business requirements. The customer's position is always defensible.

• Rule 2: Regarding the ways in which the ultimate solution is delivered, the customer is seldom “right.” The technological response to a customer's requirement lies solely with the IT solution provider except...

• Caveat to Rule 2: ...when the solution supports a specific technical requirement better understood by the customer.

Where this caveat applies, the IT organization must pay particular attention to detail to ensure that it is not missing a future service opportunity or one in which it may add value.

Jim Hackett, CEO of Steelcase, recently validated the rules just discussed as he observed the ingenuity of the popular marketing and design think-tank IDEO:

The popular notions of the last decade were for companies to become customer-centered. Theories abounded that if you paid attention to what your customer wanted, you couldn't go wrong. But the truth is that customers often ask you to do wrong things, not because they're difficult to deal with but because they just don't know better. The distinction is moving from customer-focused to user-centered, and the ability to understand the users of their products is a cultural shift that corporations have to make.

At no time do we assert that the customer is wrong or that a particular solution is wrong. It is important to note, however, that the “right-sizing” of the solution is the responsibility of IT. This is not a bad thing, but it has much to do with the strategic approach to the marketing plan.

IT is in the business of providing business solutions to business requirements. In a world becoming increasingly dependent on and conversant in technology-related matters, it is important for the IT organization to include a “perimeter defense” message in its plan. This message will assure that the correct accountability, responsibility, and authority remain with the proper players. Solutions dictated by non-IT professionals seldom meet the goals of leveragability, scalability, serviceability, and scalability (to name just a few of the “-ilities”).

It is frequently the case that the customer has seen what he deems an appropriate technology solution to his requirements. If so, you have a major marketing opportunity to harness the customer's existing buy-in to properly analyze the proposed solution, and assess (in partnership with the customer) whether it is actually appropriate. This will generally give the IT service organization a clearer understanding of the executive and departmental hot buttons and present an opportunity to focus on the more serious consequences of the final decision.

In the case of a solution that is not commercially available, the marketing process involves not only providing an appropriate solution now but one that is architecturally consistent and reliable. This gives IT a bit of a marketing challenge: How does it provide a product that is packaged properly with respect to the business customer while maintaining a flexible infrastructure within the application? Fortunately, this subject is addressed in Chapter 8, “Architecture,” but we need to keep this tension in the forefront of our marketing plan.

In the case of baseline services such as virus protection, email, dial tone, backups, recovery management, and so on, it is critical to note the built-in value of highlighting the successes buried within these tasks, which IT may consider to be mundane. Customers expect these types of tasks and services to happen but are generally unaware of their inherent complexity. The marketing opportunity lies in the advertisement of these services and their timely accomplishment to build credibility. For example, it is considered good marketing form to highlight risk mitigation activities, such as fast response to a virus threat, in the course of building this enduring credibility.

In our definition of IT marketing, we emphasized the setting of appropriate expectations but neglected to mention that it is the attractive force of those expectations that forms a bond between the customer and the product being marketed. Credibility is essential to the success or failure of the overall campaign. Put another way, the goal is to be so successful at delivering on customer requirements that the customer keeps returning freely for those services. As discussed, there are many steps involved in proficiently building credibility, and much of this is dependent on proper preparation prior to marketing the IT organization.

Before a marketing plan can be executed, the right players need to be assigned to the team. It is important to establish the appropriate level of accountability, responsibility, and authority in the overall management of the business relationship.

A marketing process for IT begins (generally) with the business relationship manager (BRM). This person's role is to act as the principal business interface with internal customers, with (responsibility for managing the customer relationship. Moreover, this person acts as a primary point of contact for all new work as well as existing support that is not meeting requirements.

The BRM conducts strategic and tactical planning, business analysis, and high-level requirements determination. This IT agent must be the person to call in the IT organization when the customer is unsure how to proceed and the voice of the customer throughout all IT groups. A senior BRM can also act as a planning and forecasting agent by conveying customer needs to the rest of the IT organization while presenting new technology opportunities to customers, and can help customers understand how to use technology toward their strategic and tactical goals.

The BRM's role can be quite complex, because he or she has complete responsibility for managing the IT/customer relationship in every regard. The BRM must take complete ownership of the supporting IT operations product as well as all SLA arrangements and criteria definition; field all customer interaction points; and be a contributor to operational reporting mechanisms. With insights into the needs of his or her particular constituency, this person establishes all of the baseline and ongoing information necessary to properly construct the marketing plan.

Because the brokering of communication between the customer and IT is an extremely time-consuming activity, the BRM must be conversant in both “business speak” (possess considerable business-domain expertise) and “technology speak” (be able to help abstract high-level business requirements into solution requirements). For this reason, it is recommended that the BRM have no direct reports, handle communication across multiple customer constituencies, and report into the IT organization.

It is rather rare to find a person in command of all of these disciplines, and the necessary skill mix is typically developed internally. The best practice for compensation of anyone in this role is to tie customer satisfaction (on an individual level, not with general IT performance) to some form of at-risk compensation. The reason for separating individual performance from IT performance is to disassociate the BRM role from conflicting business priorities, which may prevent execution of desirable customer projects.

It is also possible to be a little more creative with the mechanism of separation, as is appropriate for each situation. The key recommendation is to find a means of tying individual performance, as measured by some form of customer satisfaction (CSAT), to at-risk pay.

Once IT's marketing advocate is identified, the lifecycle shown in Figure 14-2 (borrowed from sound CRM best practices) should be applied. In short, the plan is to engage, transact, fulfill, service, and report.

Engage the customer through multiple interaction channels: face-to-face meetings, email, brown-bag lunches, or feedback sessions (CSAT surveys).

Transact business with the customer and find a means of demonstrating value in each interaction. While this might seem obvious, each meeting should have a specific purpose and identified outcomes. One value that IT brings to the table is a keen sense of process, and the customer must be reminded that there is progress to be made from each interaction. The BRM is the evangelist for the customer within IT and to the customer on behalf of IT.

Fulfillment is the stage at which the customer realizes the benefits of the IT involvement in helping to meet business requirements. The realization may be through the production of working modules, status reports, milestone meetings, progress reports, or other means. The precise form of the fulfillment is directly dependent on the customer and the project, but the net effect is to complete iterative feedback cycles in which the customer realizes the value of IT's involvement.

Servicing the customer is a frequently overlooked step in the lifecycle of CRM. This is especially true if the prior three steps are highly successful in the customer's eyes. An investment in the adage “If it works, don't fix it” is the start of entropy, which inhibits proactive solicitation of status from the customer (“How are we doing?”) and will backfire in the next iteration of customer interaction.

Reporting is the most important mechanism in the campaign for customer loyalty. Marketing the IT organization does not mean that IT should publish only compliance reports. The good, the bad, and the ugly need to be routinely communicated while developing trust in the customer relationship. If there is a belief that reporting is merely a vehicle for spin doctoring, the relationship will never evolve into a true partnership.

Metrics are the all important cornerstone on which the reporting phases rest. Many ideas are presented in other chapters of this book; refer to Chapter 15, “The Metrics of IT,” for details on the development of measures relevant to the customer as well as IT. Topics of common interest are

• Internal versus external performance (benchmarking).

• Efficiency.

• Effectiveness.

• Capability.

• Financial report/budgets.

• SLAs.

Carefully consider the mechanism by which you communicate feedback to the customer. Not only is the function of the communication vehicle important, but also its form can make or break the communication. It is a commonly held belief that IT cannot speak the language of its customers; customers wonder what language IT actually speaks. This is perpetuated in everyday activities such as mass mailings providing status on outages (if these appear at all).

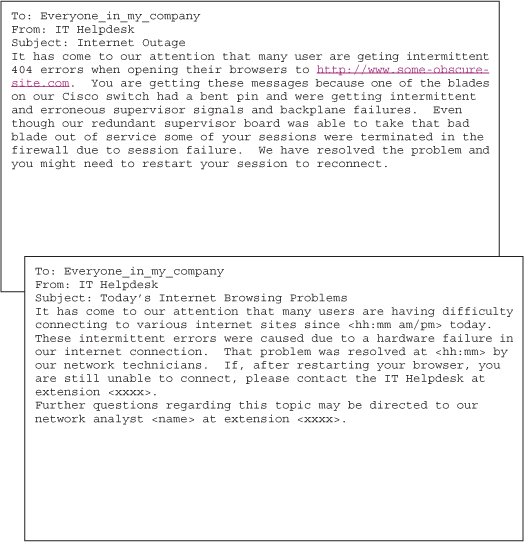

The two messages shown in Figure 14-3 are intended to inform the customer base of an intermittent outage. Messages like these, though routine, must consistently reflect thoughtful and deliberate structure so customers can extract only the relevant information necessary to perform their part.

The first example is not only questionable in terms of technical accuracy, but provides nearly zero useful information to the customer. There are numerous problems with this first message: irrelevant verbiage containing no context for the customer, superfluous information, misspellings, grammatical errors, and copious IT jargon. Although this level of reporting may be relevant in some form of post-mortem with other technologists, it will be swiftly ignored and deleted by the very audience to which it is addressed. It invites the criticism that IT misuses its own resources.

The second example is much clearer and contains only the information relevant to the customer community. The closing line is a marketing tactic that is becoming more frequently used; it helps bring some transparency to the otherwise opaque help desk.

This is also consistent with the marketing “messages” requested by the user community. The criticism received by this company's IT department is that they are a “black hole”; providing the option of asking for details and assigning a named technician is an open-kimono message, which may or may not apply to other organizations.

Conventional IT wisdom tends to hold that technicians must remain anonymous so they may “get their work done,” but it also is a dangerous practice, which reinforces an impersonal view of the department. The key attributes of the second message, in addition to grammatical and technical accuracy, are its brevity and relevance to the broadest community. The message answers only the basic reporter's questions: Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? Though these may appear to be contrived samples, they are frighteningly close to real-life examples we have received.

Each and every customer communication is another marketing opportunity. If the value proposition to the customer community is being in tune with the customer community, all communications must reflect that message regardless of the mode or channel. Simple and routine actions such as using email to communicate a failure of email or the network can do more to undermine a well-crafted marketing plan than any other routine activity.

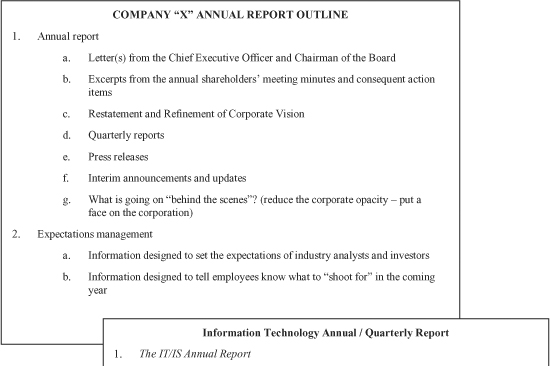

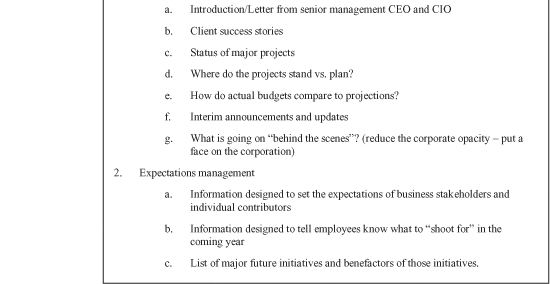

Another marketing vehicle, which requires no significant invention, is a model provided by publicly held companies and forward thinking private companies—the annual report. This report contains metrics, has an established frequency, is a well-understood vehicle with consistent contents, and targets an interested constituency. Figure 14-4 compares a corporate annual report with an IT annual or quarterly report.

The corporate intranet is an invaluable vehicle for information delivery, but it is not uncommon for IT to be the shoemaker's children (who don't wear shoes) when it comes to the appropriate monitoring and management of its own content. Companies using Web-based technology for information dissemination must maintain the content properly, or the delivery vehicle becomes useless. It is a common worst practice to simply publish an intranet and forget about site traffic analysis. Knowing the traffic patterns of customers through the Web site is a fundamental indicator to understanding the effectiveness of the delivery vehicle.

Finally, the “human touch” cannot be underestimated and is a strategic element in garnering customer connections. Various forms of reaching out to the customer community can provide tangible value in simple activities such as brown-bag lunches, data center tours, and open house functions.