CHAPTER 5

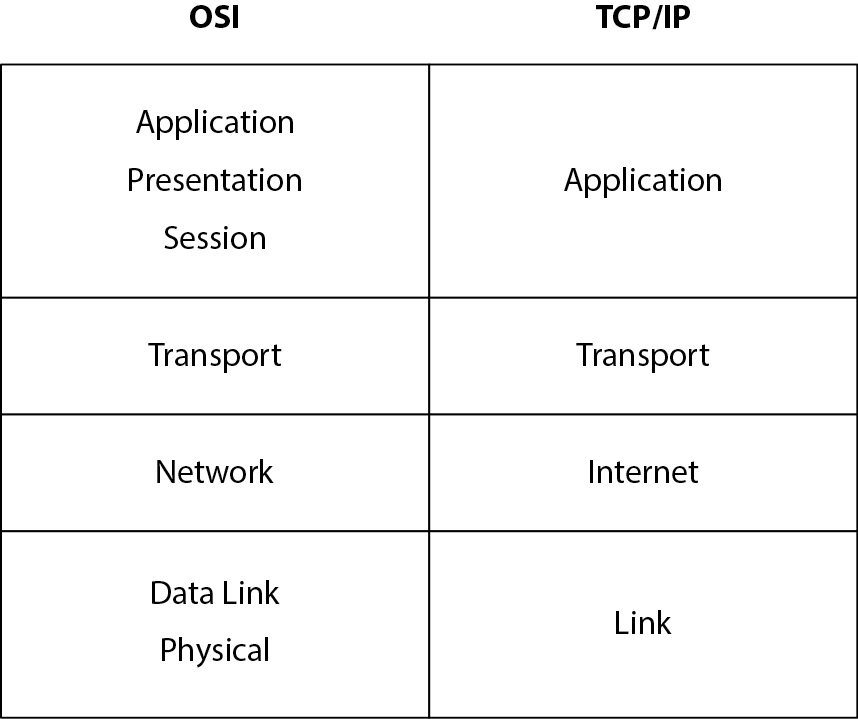

IT Service Management and Continuity

This chapter covers CISA Domain 4, “Information Systems Operations and Business Resilience,” and discusses the following topics:

• Information systems operations

• Information systems hardware

• Information systems architecture and software

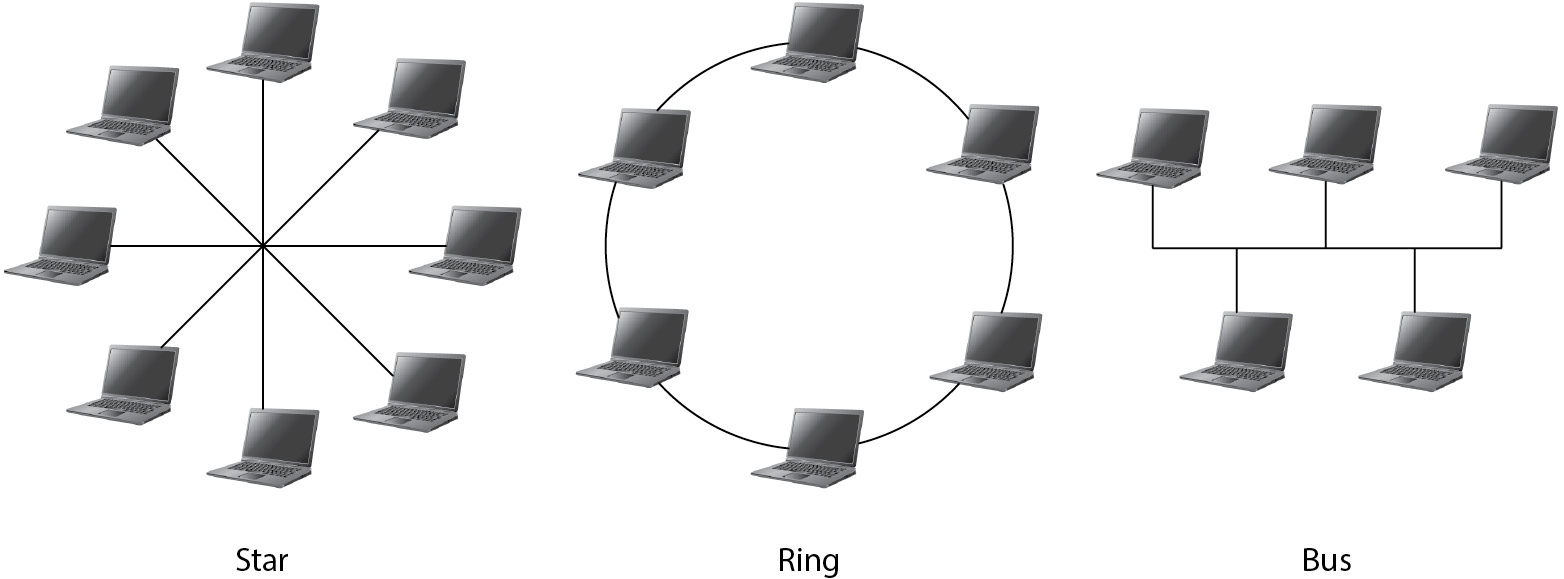

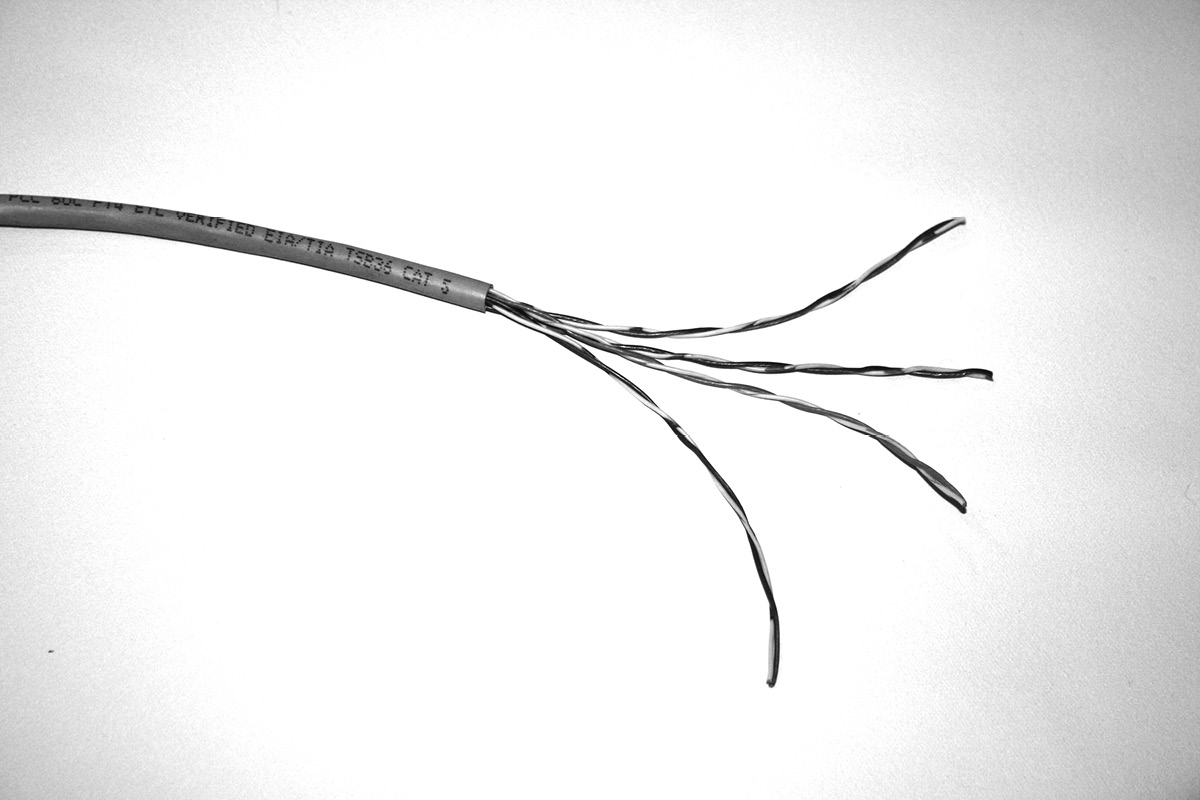

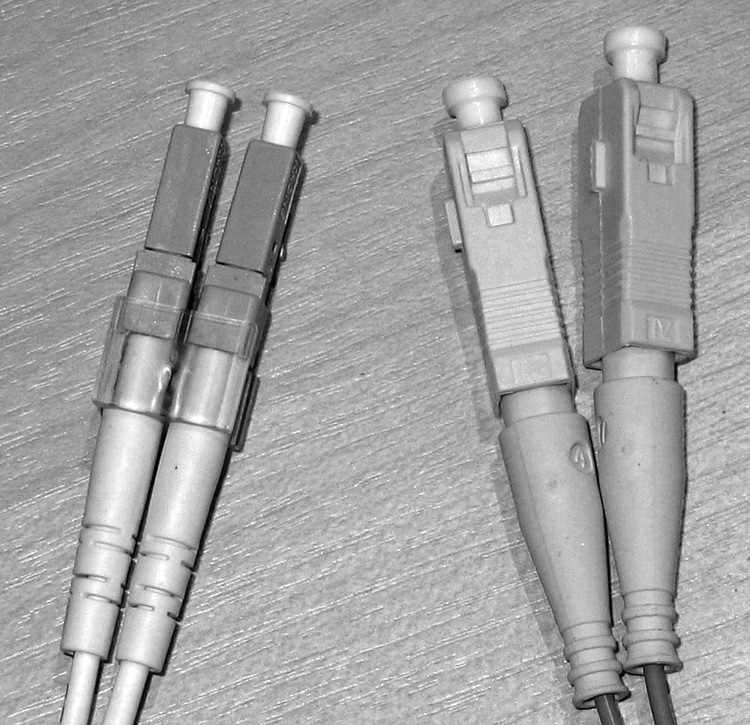

• Network infrastructure, technologies, models, and protocols

• Business continuity and disaster recovery planning

• Auditing infrastructure, operations, business continuity and disaster recovery planning

The topics in this chapter represent 23 percent of the CISA examination.

IT organizations are effective if their operations are effective. Management needs to be in control of information systems operations, which means that all aspects of operations need to be measured, those measurements and reports reviewed, and management-directed changes carried out to ensure continuous improvement.

IT organizations are service organizations—they exist to serve the organization and support its business processes. IT’s service management operations need to be well designed, adequately measured, and reviewed by management.

In the age of digital transformation (DX), organizations are more dependent than ever before on information technology for execution of core business processes. This, in turn, changes the business resilience conversation and increases the emphasis on business continuity and disaster recovery planning, which has moved to this domain in the 2019 CISA job practice.

In addition to being familiar with IT business processes, IS auditors need to have a keen understanding of the workings of computer hardware, operating systems, and network communications technology. This knowledge will help the auditor better understand many aspects of service management and operations.

Information Systems Operations

IS operations encompass the day-to-day control of the information systems, applications, and infrastructure that support organizational objectives and processes. IS operations is composed of several sets of activities, which include management and control of operations:

• IT service management

• IT operations and exception handling

• End-user computing

• Software program library management

• Quality assurance

• Security management

• Media control

• Data management

These activities are discussed in detail in the remainder of this section, following a brief overview describing how IS operations need to be managed and controlled.

Management and Control of Operations

All of the activities that take place in an IT department should be managed and controlled. This means that all actions and activities performed by operations personnel should be a part of a control, procedure, process, or project that has been approved by management. Processes, procedures, and projects should have sufficient recordkeeping so that management can understand the statuses of these activities.

Management is ultimately responsible for all activities that take place in an IS operations department. The primary high-level management activities that govern IS operations are

• Development of processes and procedures Every repetitive activity performed by any operations personnel should be documented in the form of a process or procedure. This means that documents that describe each step of every process and procedure need to be developed, reviewed, approved by management, and made available to operations staff.

• Development of standards From the way that operations perform tasks to the brands and technologies used, standards drive consistency in everything that IS operations does.

• Resource allocation Management is responsible for allocating resources that support IS operations, including manpower, technology, and budget. Resource allocation should align with the organization’s mission, goals, and objectives.

• Process management All IS operations processes should be measured and managed. This will ensure that processes are being performed properly, accurately, and within time and budget targets.

IT Service Management

IT service management (ITSM) is the set of activities that ensures the delivery of IT services is efficient and effective, through active management and the continuous improvement of processes.

ITSM consists of several distinct activities:

• Service desk

• Incident management

• Problem management

• Change management

• Configuration management

• Release management

• Service-level management

• Financial management

• Capacity management

• Service continuity management

• Availability management

Each of these activities is described in detail in this section.

ITSM is formally defined in the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) process framework, a well-recognized standard. The content of ITIL is managed by AXELOS. ITSM processes can be audited and registered to the ISO/IEC 20000:2011 standard, the international standard for ITSM.

Service Desk

Often known as the helpdesk or call center, the IT service desk function handles incidents and service requests on behalf of internal IT customers by acting as a single point of contact. The service desk performs end-to-end management of incidents and service requests (at least from the perspective of the customer) and also is responsible for communicating status reports to the customer for matters that take more time to resolve.

The service desk can also serve as a collection point for other ITSM processes, such as change management, configuration management, service-level management, availability management, and other ITSM functions.

Incident Management

ITIL defines an incident as “an unplanned interruption to an IT service or reduction in the quality of an IT service. Failure of a configuration item that has not yet affected service is also an incident—for example, failure of one disk from a mirror set.”

Thus, an incident may be any of the following:

• Service outage

• Service slowdown

• Software bug

Regardless of the cause, incidents are a result of failures or errors in any component or layer in IT infrastructure.

In ITIL terminology, if the incident has been experienced before and its root cause is known, this is a known error. If the service desk is able to access the catalog of known errors, this may result in more rapid resolution of incidents, resulting in less downtime and inconvenience. The change management and configuration management processes are used to make modifications to the system in order to fix it temporarily or permanently.

If the root cause of the incident is not known, the incident may be escalated to a problem, which is discussed in the next section.

Problem Management

When several incidents have occurred that appear to have the same or a similar root cause, a problem is occurring. ITIL defines a problem as “a cause of one or more incidents.”

The overall objective of problem management is the reduction in the number and severity of incidents.

Problem management can also include some proactive measures, including system monitoring to measure system health and capacity management that will help management to forestall capacity-related incidents.

Examples of problems include

• A server that has exhausted available resources that result in similar, multiple errors (which, in ITSM terms, are known as incidents)

• A software bug in a service that is noticed by and affecting many users

• A chronically congested network that causes the communications between many IT components to fail

Similar to incidents, when the root cause of a problem has been identified, the change management and configuration management processes will be enacted to make temporary and permanent fixes.

Change Management

Change management is the set of processes that ensures all changes performed in an IT environment are controlled and performed consistently. ITIL defines change management as follows: “The goal of the change management process is to ensure that standardized methods and procedures are used for efficient and prompt handling of all changes, in order to minimize the impact of change-related incidents upon service quality, and consequently improve the day-to-day operations of the organization.”

The main purpose of change management is to ensure that all proposed changes to an IT environment are vetted for suitability and risk, and to ensure that changes will not interfere with each other or with other planned or unplanned activities. To be effective, each stakeholder should review all changes so that every perspective of each change is properly reviewed.

A typical change management process is a formal “waterfall” process that includes the following steps:

1. Proposal or request The person or group performing the change announces the proposed change. Typically, a change proposal contains a description of the change, the change procedure, the IT components that are expected to be affected by the change, a verification procedure to ensure that the change was applied properly, a back-out procedure in the event the change cannot be applied (or failed verification), and the results of tests that were performed in a test environment. The proposal should be distributed to all stakeholders several days prior to its review.

2. Review This is typically a meeting or discussion about the proposed change, where the personnel who will be performing the change can discuss the change and answer stakeholders’ questions. Since the change proposal was sent out earlier, each stakeholder should have had an opportunity to read about the proposed change in advance of the review. Stakeholders can discuss any aspect of the change during the review. The stakeholders may agree to approve the change, or they may request that it be deferred or that some aspect of the proposed change be altered.

3. Approval When a change has been formally approved in the review step, the person or group responsible for change management recordkeeping will record the approval, including the names of the individuals who consented to the change. If, however, a change has been deferred or denied, the person or group that proposed the change will need to make alterations to the proposed change so that it will be acceptable, or they can withdraw the change altogether.

4. Implementation The actual change is implemented per the procedure described in the change proposal. Here, the personnel identified as the change implementers perform the actual change to the IT system(s) identified in the approved change procedure.

5. Verification After the implementers have completed the change, they will perform the verification procedure to make sure that the change was implemented correctly and that it produces the desired result. Generally, the verification procedure will include one or more steps that include the gathering of evidence (and directions for confirming a correct versus an incorrect change) that shows the change is correct. This evidence will be filed with other records related to the change and may be useful in the future if there is any problem with the system where this change is suspected as a part of the root cause.

6. Post-change review Some or all changes in an IT organization will be reviewed after the change is implemented. In this activity, the personnel who made the change discuss the change with other stakeholders to learn more about the change and whether any updates or future changes may be needed.

These activities should be part of the duties of a change control board, a group of stakeholders from IT and every group that is affected by changes in IT applications and supporting infrastructure.

Change Management Records Most or all of the activities related to a change should include updates to business records so that all of the facts related to each change are captured for future reference. In even the smallest IT organization, there are too many changes taking place over time to expect that anyone will be able to recall facts about each change later on. Records that are related to each change serve as a permanent record.

Emergency Changes Though most changes can be planned in advance using the change management process described here, there are times when IT systems need to be changed right away. Most change management processes include a process for emergency changes that details most of the steps in the nonemergency change management process, but they are performed in a different order. The steps for emergency changes are

• Emergency approval When an emergency situation arises, the staff members attending to the emergency should still seek management approval for the proposed change. This approval may be done by phone, in person, or in writing (typically, e-mail). If the approval was by phone or in person, e-mail or other follow-up communication is usually performed. Certain members of management should be designated in advance who can approve these emergency changes.

• Implementation Staff members perform the change.

• Verification Staff members verify that the change produced the expected result. This may involve other staff members from other departments or end users.

• Review The emergency change is formally reviewed. This review may be performed alongside nonemergency changes with the change control board, the same group of individuals who discuss nonemergency changes.

Like nonemergency changes, emergency changes should be fully documented with records made available for future reference.

Linkage to Problem and Incident Management Often, changes are made as a result of an incident or problem. Emergency and nonemergency changes should reference specific incidents or problems so that those incidents and problems may be properly closed once verification of their resolution has been completed.

Configuration Management

Configuration management (CM) is the process of recording the configuration of IT systems. Each configuration setting is known in ITSM parlance as a configuration item (CI). CIs usually include the following:

• Hardware complement This includes the hardware specifications of each system (such as CPU speed, amount of memory, firmware version, adaptors, and peripherals).

• Hardware configuration Settings at the hardware level may include boot settings, adaptor configuration, and firmware settings.

• Operating system version and configuration This includes versions, patches, and many operating system configuration items that have an impact on system performance and functionality.

• Software versions and configuration Software components such as database management systems, application servers, and integration interfaces often have many configuration settings of their own.

Organizations that have many IT systems may automate the CM function with tools that are used to record and change configuration settings automatically. These tools help to streamline IT operations and make it easier for IT systems to be more consistent with one another. The database of system configurations is called a configuration management database (CMDB).

Linkage to Problem and Incident Management An intelligent problem and incident management system is able to access the CMDB to help IT personnel determine whether incidents and problems are related to specific configurations. This can be a valuable aid to those who are seeking to determine a problem’s root cause.

Linkage to Change Management Many configuration management tools are able to detect system configuration changes automatically. With some change and configuration management systems, it is possible to correlate changes detected by a configuration management system with changes approved in the change management process. Further, many changes that are approved by the change management process can be performed by configuration management tools, which can be used to push changes out to managed systems.

Release Management

Release management is the ITIL term used to describe the portion of the SDLC where changes in applications and other information systems are placed into production and made available to end users. Release management is used to control the changes that are made to software programs, applications, and environments.

The release process is used for several types of changes to a system, including the following:

• Incidents and problem resolution Casually known as bug fixes, these types of changes are done in response to an incident or problem, where it has been determined that a change to application software is the appropriate remedy.

• Enhancements New functions in an application are created and implemented. These enhancements may have been requested by customers, or they may be a part of the long-range vision on the part of the designers of the software program.

• Subsystem patches and changes Changes in lower layers in an application environment may require a level of testing that is similar to what is used when changes are made to the application itself. Examples of changes are patches, service packs, and version upgrades to operating systems, database management systems, application servers, and middleware.

The release process is a sequential process—that is, each change that is proposed to an information system will be taken through each step in the release management process. In many applications, changes are usually assembled into a “package” for process efficiency purposes: it is more effective to discuss and manage groups of changes than it would be to manage individual changes.

The steps in a typical release process are preceded by typical SDLC process steps:

1. Feasibility study This study seeks to determine the expected benefits of a program, project, or change to a system.

2. Requirements definition Each software change is described in terms of a feature description and requirements. The feature description is a high-level description of a change to software that may explain the change in business terms. Requirements are the detailed statements that describe a change in enough detail for a developer to make changes and additions to application code that will provide the desired functionality. Often, end users will be involved in the development of requirements so that they may verify that the proposed software change is really what they desire.

3. Design After requirements have been developed, a programmer/analyst or application designer will create a formal design. For an existing software application, this will usually involve changes to existing design documents and diagrams, but new applications will need to be created from scratch or copied from similar designs and modified. Regardless, the design will have a sufficient level of detail to permit a programmer or software engineer to complete development without having to discern the meaning of requirements or design.

4. Development When the requirements definition and design have been completed, reviewed, and approved, programmers, software engineers, or other IT engineers begin development. This involves actual coding in the chosen computer language with approved development tools, as well as the creation or update to ancillary components, such as a database design or application programming interface (API). Developers will often perform their own unit testing, where they test individual modules and sections of the application code to make sure that it works properly. In other cases, development will consist of planned configuration changes, patch application, or module upgrades made to an information system.

5. Testing When the developers have finished coding and unit testing (or other engineers have completed their initial work), a more formal and comprehensive test phase is performed. Here, analysts, dedicated software or systems testers, and perhaps end users, will test all of the new and changed functionality to confirm whether it is performing according to requirements. Depending on the nature of the changes, some amount of regression testing is also performed; this means that functions that were confirmed to be working properly in prior releases are tested again to make sure that they continue to work as expected. Testing is performed according to formal, written test plans designed to confirm that every requirement is fulfilled. Formal test scripts are used, and the results of all tests should be recorded and archived. The testing that users perform is usually called user acceptance testing (UAT). Often, automated test tools are used, which can make testing more accurate and efficient. After testing is completed, a formal review and approval are required before the process is allowed to continue.

6. Implementation When testing has been completed, the changes are implemented on production systems. Here, developers hand off the completed software or system changes to operations personnel, who install it according to instructions created by developers. This could also involve the use of tools to make changes to data and database design, operating systems, or network devices, to accommodate changes in the system. When changes are completed and tested, the release itself is carried out with these last two steps:

a. Release preparation When UAT and regression testing have been completed, reviewed, and approved, a release management team will begin to prepare the new or changed system for release. Depending upon the complexity of the system and of the change itself, release preparation may involve not only software (or another component) installation but also the installation or change to database design, operating systems, network devices, and perhaps even customer data. Hence, the release may involve the development (or engineering) and testing of data conversion tools and other programs that are required so that the new or changed system will operate properly. As with testing and other phases, full records of testing and implementation of release preparation details need to be captured and archived.

b. Release deployment When release preparation is completed (and perhaps reviewed and approved), the release is installed on the target system(s). Personnel deploying the release will follow the release procedure, which may involve the use of tools that will make changes to the target system at the operating system, database, or other level; any required data manipulation or migration; and the installation of the actual software. The release procedure will also include verification steps that will be used to confirm the correct installation of all components.

7. Post-Implementation After system changes have been implemented, a post-implementation review takes place to examine matters of system adequacy, security, ROI, and any issues encountered during implementation.

Utilizing a Gate Process Many organizations utilize a “gate process” approach in their release management process. This means that each step of the process undergoes formal review and approval before the next step is allowed to begin. For example, a formal design review will be performed and attended by end users, personnel who created requirements and feature description documents, developers, and management. If the design is approved, development may begin. But if there are questions or concerns raised in the design review, the design may need to be modified and reviewed again before development is allowed to begin.

Agile processes utilize gates as well, although the flow of agile processes is often parallel rather than sequential. The concept of formal reviews is the same, regardless of the SDLC process in use.

Service-Level Management

Service-level management is composed of the set of activities that confirms whether IS operations are providing adequate services to customers. This is achieved through continuous monitoring and periodic review of IT service delivery.

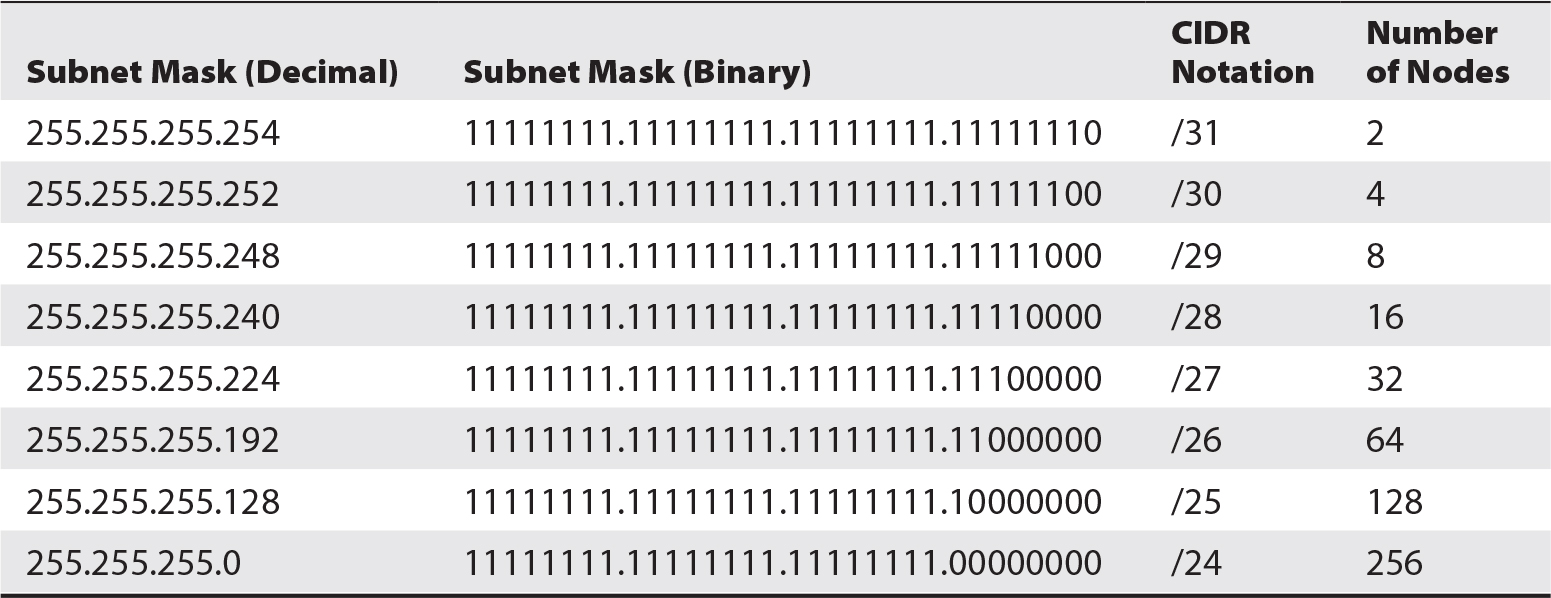

An IT department often plays two different roles in service-level management. As a provider of service to its own customers, the IT department will measure and manage the services that it provides directly. Also, many IT departments directly or indirectly manage services that are provided by external service providers. Thus, many IT departments are both service provider and customer, and often the two are interrelated. This is depicted in Figure 5-1.

Figure 5-1 The different perspectives of the delivery of IT services

Financial Management

Financial management for IT services consists of several activities, including

• Budgeting

• Capital investment

• Expense management

• Project accounting and project return on investment (ROI)

IT financial management is the portion of IT management that takes into account the financial value of IT services that support organizational objectives.

Capacity Management

Capacity management is a set of activities that confirms that sufficient capacity exists in IT systems and IT processes to meet service needs. Primarily, an IT system or process has sufficient capacity if its performance falls within an acceptable range, as specified in service level agreements (SLAs).

Capacity management is not just a concern for current needs; it must also consider future needs. This is attained through several activities, including

• Periodic measurements Systems and processes need to be regularly measured so that trends in usage can be used to predict future capacity needs.

• Considering planned changes Planned changes to processes and IT systems may have an impact on predicted workload.

• Understanding long-term strategies Changes in the organization, including IT systems, business processes, and organizational objectives, may have an impact on workloads, requiring more (or less) capacity than would be extrapolated through simpler trend analysis.

• Changes in technology Several factors may influence capacity plans, including the expectation that computing and network technologies will deliver better performance in the future and that trends in the usage of technology may influence how end users use technology.

Linkage to Financial Management One of the work products of capacity management is a projection for the acquisition of additional computer or network hardware (whether physical devices or virtual in-the-cloud workloads) to meet future capacity needs. This information needs to be made a part of budgeting and spending management processes.

Linkage to Service Level Management If there are insufficient resources to handle workloads, capacity issues may result in violations to SLAs. Systems and processes that are overburdened will take longer to respond. In some cases, systems may stop responding altogether.

Linkage to Incident and Problem Management Systems with severe capacity issues may take excessive time to respond to user requests. In some cases, systems may malfunction or users may give up. Often, users will call the service desk, resulting in the logging of incidents and problems.

Service Continuity Management

Service continuity management is the set of activities that is concerned with the ability of the organization to continue providing services, primarily when a natural or manmade disaster has occurred. Service continuity management is ITIL parlance for the more common terms business continuity planning and disaster recovery planning.

Business continuity and disaster recovery are discussed later in this chapter.

Availability Management

The goal of availability management is to sustain IT service availability in support of organizational objectives and processes. The availability of IT systems is governed by

• Effective change management When changes to systems and infrastructure are properly vetted through a change management process, changes are less likely to result in unanticipated downtime.

• Effective system testing When changes to systems are made according to a set of formal requirements, review, and testing, the system is less likely to fail and become unavailable.

• Resilient architecture When the overall architecture of an environment is designed from the beginning to be highly reliable, it will be more resilient and more tolerant of individual faults and component failures.

• Serviceable components When the individual components of an environment can be effectively serviced by third-party service organizations, those components will be less likely to fail unexpectedly.

IT Operations and Exception Handling

Effective IT operations require that IT personnel understand and properly carry out operational tasks according to established processes and procedures. Personnel must also be trained to recognize exceptions and errors and to respond to them accordingly. The tasks that may be included in IT operations include

• Running jobs according to the job schedule

• Monitoring jobs and allocating resources to jobs based on priority

• Restarting failed jobs and processes

• Facilitating backup jobs by loading or changing backup media, or by ensuring readiness of target storage systems

• Monitoring systems, applications, and networks for availability and adequate performance

• Performing after-hours maintenance activities such as equipment cleaning and system restarts

IT organizations often employ a production schedule, which is a list of activities or tasks that are carried out periodically (daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and so on). Scheduled activities consist of system-borne activities such as backups as well as human-performed activities such as access reviews, reconciliations, and month-end close. Scheduled activities in systems may be automatically scheduled or manually invoked.

Larger organizations may have a network operations center (NOC) and perhaps also a security operations center (SOC), staffed by personnel who monitor activities in the organization’s security devices, networks, systems, and applications. Often, some or all of these activities are outsourced to a managed security service provider (MSSP).

Exceptions and errors that occur within the context of IT operations are typically handled according to ITSM incident management and problem management processes, which were discussed in the preceding section.

Monitoring

Information systems, applications, and supporting infrastructure must be monitored to ensure that they continue to operate as required.

Monitoring tools and programs enable IT operations staff to detect when software or hardware components are not operating as planned. The IT operations staff must also make direct observations in order to detect some problems. The types of errors that should be detected and reported include

• System errors

• Program errors

• Communications errors

• Operator errors

Simply put, any event that represents unexpected or abnormal activity should be recorded so that management and customers may become aware of it. This requires that incident and problem management processes be developed. Incident and problem management are discussed in detail in the earlier section “IT Service Management.”

Security Monitoring

Many organizations perform several types of security monitoring as a part of their overall strategy to prevent and respond to security incidents. The types of monitoring that an organization may perform include

• Firewall exceptions

• Intrusion prevention system (IPS) alerts

• Data loss prevention (DLP) system alerts

• Cloud security access broker (CASB) alerts

• User access management system alerts

• Network anomaly alerts

• Web content filtering system alerts

• Endpoint management system alerts, including anti-malware

• Vendor security advisories

• Third-party security advisories

• Threat intelligence advisories

• Work center access system alerts

• Video surveillance system alerts

End-User Computing

A critical portion of an IT organization’s function is the services it renders to organization personnel to facilitate their access and use of IT systems and applications. Operational models for supporting end-user computing include

• Organization-provided hardware and software The organization provides all computing devices (typically, laptop or desktop computers and perhaps mobile computing devices such as tablets or smartphones) and software.

• Personnel-provided hardware and software The organization provides network infrastructure and instructions on how end users may configure their computing devices to access the organization’s IT applications and systems. Some organizations provide a stipend to its personnel to pay for all or part of the costs of end-user computers.

• Hybrid models Many organizations employ a hybrid of the organization and personnel models. Often, an organization provides laptop or desktop computers, and employees are permitted to access e-mail and some organization applications via personally owned devices such as home computers, tablets, and smartphones.

Usually the organization will employ enterprise management tools to facilitate efficient and consistent management of end-user computers. Typically, end-user computers are “locked down,” which limits the amount of and types of configuration changes that end users may perform on their devices, including

• Operating system configuration

• Patch installation

• Software program installation

• Use of external data storage devices

Such restrictions may be viewed by end users as an inconvenience. However, these restrictions not only help to ensure greater security of end-user devices and the entire organization’s IT environment, but they also promote greater consistency, which leads to reduced support costs.

Some organizations employ a zero trust model for end-user computing. This approach is sometimes used in conjunction with BYOD (bring your own device), where end users provide their own computing devices.

Software Program Library Management

The software program library is the facility that is used to store and manage access to an application’s source and object code.

In most organizations, application source code is highly sensitive. It may be considered intellectual property, and it may contain information such as algorithms, encryption keys, and other sensitive information that should be accessed by as few persons as possible. In a very real sense, application source code should be considered information and be treated as such through the organization’s security policy and data classification policy.

A software program library often exists as an information system with a user interface and several functions, including the following:

• Access and authorization controls The program library should uniquely identify all individuals who attempt to access it and authenticate them with means that are commensurate with the sensitivity of the application. The program library should be able to manage different roles or levels of access so that each person is able to perform only the functions that they are authorized to perform. Also, the program library should be able to restrict access to different modules or applications stored within it; for example, source code that is more sensitive (such as the code related to access control or data encryption) should be accessible by fewer personnel than less sensitive source code.

• Program check-out This means that an authorized user is able to access some portion of application source code, presumably to make a modification or perform analysis. Check-out permits the user to make a copy of the source code module that might be stored elsewhere in the program library or on another computer. Often, check-out is permitted only upon management approval, or it may be integrated with a defect tracking system so that a developer is permitted to check out a piece of source code only if there is a defect in the program that has been assigned to the particular developer. When source code is checked out, the program library typically “locks” that section of source code so that another developer is not able to also check it out—thus preventing a “collision” where two developers are making changes to the same section of code at the same time.

• Program check-in This function enables an authorized user to return a section of application source code to the program library. A program library will usually permit only the person who checked out a section of code to check it back in. If the user who is checking in the code section made modifications to it, the program library will process those changes and may perform a number of additional functions, including version control and code scanning. If the section of code being checked in was locked, the program library will either automatically unlock it or ask the user whether it should remain locked if, for example, additional changes are to be made.

• Version control This function enables the program library to manage changes to the source code by tracking the changes that are made to it each time it is checked in. Each time a source code module is modified, an incremented “version number” is assigned. This enables the program library to recall any prior version of a source code module at any time in the future. This can be useful during program troubleshooting or investigations into a particular programmer’s actions.

• Code analysis Some program library systems can perform different types of code analysis when source code is checked in. This may include a security scan that will examine the code for vulnerabilities or a scan that will determine whether the checked-in module complies with the organization’s coding policies and standards.

These controls enable an organization to have a high degree of control over the integrity and, hence, quality and security of its software applications.

Quality Assurance

The purpose of quality assurance (QA) is to ensure that changes to software applications, operating system configuration, network device configuration, and other information systems components are performed properly. Primarily, this is carried out through independent verification of work.

QA can be carried out within most IT processes, including but not limited to

• Software development

• Change management

• Configuration management

• Service management

• Incident management

• Problem management

• Business process development

As a result of QA activities, improvements in accuracy and efficiency are sought and processes and systems are changed.

Security Management

Information security management is the collection of high-level activities that ensures that an organization’s information security program is adequately identifying and addressing risks and operating properly overall. An information security management program usually consists of several activities:

• Development of security policy, processes, procedures, and standards

• Risk assessment and risk management

• Vulnerability management

• Incident management

• Security awareness training

In some organizations, security management also includes disaster recovery planning and business continuity planning.

Security management is discussed in detail in Chapters 2 and 6.

Media Control

Security standards and privacy laws have highlighted the need for formal processes to ensure the proper management of digital media, including its protection as well as destruction of data that is no longer needed. These processes are usually associated with data retention and data purging procedures so that data that is needed is adequately protected with physical and logical security controls, and data that is no longer needed is effectively discarded and erased. Procedures related to the disposal of media that is no longer needed now include steps to erase data on that media or make the data on that media irretrievable in another way.

Media that should be considered in scope for media management and destruction policies and procedures include

• Backup media

• Virtual tape libraries

• Optical media

• Hard drives and solid-state drives

• Flash memory in computers, network devices, disk drives, workstations, mobile devices, and portable USB storage devices

• Hard drives in printers, copiers, and scanners

• Hard copy

Policies and procedures for media sanitization need to be included in service provider contracts, as well as recordkeeping to track the destruction of media over time.

Media control is closely related to data management, discussed in the next subsection.

Data Management

Data management is the set of activities related to the acquisition, processing, storage, use, and disposal of data.

Arguably the most important activity in data management is planning. As with most human endeavors, data management activities have far better outcomes when planning precedes action. Mainly this is related to data architecture, which is the set of activities related to the design of databases and the flows of information between databases, systems, and organizations.

Data Life Cycle

The data life cycle is the set of activities that take place throughout the use of data in an organization. The phases of the data life cycle are

• Planning Prior to the creation or acquisition of data, the organization needs to understand its structure, its sensitivity and value, its use, and its eventual destruction.

• Design This is the actual process of creating the structure and protection of data. Typical activities at this stage include the creation of a database schema and configuration of physical and logical storage systems that will store databases.

• Build/acquire In this phase, data is created or imported from another system.

• Operations In this phase, data is processed, shared, and used.

• Monitoring This includes examination of the data itself as well as activities related to the access and use of data to ensure that the data retains its quality and that it is protected from misuse and harm.

• Archival This is related to any long-term storage of data for legal or historical purposes.

• Disposal This is related to the discarding or erasure process that takes place at the end of the useful life of a set of data.

Data Quality Management

Data quality management encompasses several activities to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and completeness of data. Activities in data quality management include

• Application controls Measures to ensure that applications enforce the integrity and completeness of data. This topic is covered in Chapter 4.

• Systems development Measures to ensure that applications that are developed or acquired enforce the integrity and completeness of data. This topic is covered in Chapter 4.

• Systems integrity Measures to ensure that information systems enforce the confidentiality and integrity of data. This topic is covered in Chapter 6.

Information Systems Hardware

Hardware is the elemental basis of information systems. It consists of circuit boards containing microprocessors and memory; other components connected through circuitry, such as hard disk drives or solid-state drives; and peripherals such as keyboards, printers, monitors, and network connections.

IS auditors need to understand at least the basic concepts of computer hardware architecture, maintenance, and monitoring so that they can properly assess an organization’s use and care of information systems hardware. A lack of knowledge in this area could result in the auditor overlooking or failing to understand important aspects of an organization’s operations.

The macro trend toward the use of cloud computing infrastructure versus on-premises computer hardware does not preclude the need to be familiar with the concepts of computing hardware. Although contact with computer hardware is absent when an organization is managing virtual workloads, organizations utilizing cloud-based infrastructure still need to be familiar with hardware concepts; this is applied through the configuration of virtual servers and the resources they use. Further, computer hardware is still used by end users in the form of desktop and laptop computers as well as tablet computers and smartphones.

Computer Usage

Computers are manufactured for a variety of purposes and contexts and are used for many different purposes. They can be classified by their capacity, throughput, size, use, or the operating system or software that they use.

Types of Computers

From a business perspective, computers are classified according to their size and portability. In this regard, the types of computers are

• Supercomputer These are the largest computers in terms of the number and/or power of their central processing units (CPUs). Supercomputers are generally employed for scientific applications such as weather and climate forecasting, seismology, and other computer-intensive applications.

• Mainframe These business workhorse computers are designed to run large, complex applications that operate on enormous databases or support vast numbers of users. When computing began, mainframes were the only kind of computer; most of the other types were derived from the mainframe. Today, mainframes are still commonly used for larger financial transaction systems and other large-scale applications such as airline reservation systems.

• Midrange These computers are not as large and powerful as mainframe computers, but they are larger or more powerful than small servers. There are no hard distinctions between these sizes of computers, but only vague, rough guidelines.

• Server If mainframe computers are the largest business servers, the ordinary server is the smallest. In terms of its hardware complement and physical appearance, a server can be indistinguishable from a user’s desktop computer.

• Blade server In this style of hardware design, servers are modules that plug in to a cabinet. Each module contains all of the internal components of a stand-alone computer. The cabinet itself will contain power supplies and network connectors.

• Virtual server This is a cloud-based server that exists in a hypervisor environment, whether in an on-premises private cloud or a public cloud.

• Appliance This type of computer typically comes with one or more tools or applications preinstalled. The term “appliance” is sometimes used to connote the fact that little or no maintenance is required on the system.

• Desktop This is a computer that is used by an individual worker. Its size makes it fairly easy to move from place to place, but it is not considered portable. The desktop computers of today are more powerful in many ways than the mainframe computers of a few decades ago. Desktop computers used to be called microcomputers, but the term is seldom used now.

• Laptop/notebook This computer is portable in every sense of the word. It is self-contained, equipped with a battery, and folds for storage and transport. Functionally, desktop and laptop computers are nearly identical: they may run the same operating system and programs.

• Mobile These computers come in the form of smartphones and tablet devices.

• Embedded These computers are built into products such as televisions, automobiles, medical devices, and many other industrial and consumer devices.

Uses for Computers

Aside from the sizes and types of computers discussed in the previous section, computers may also be used for several reasons, including

• Application server This computer—usually a mainframe, midrange, or server—runs application-server software. An application server contains one or more application programs that run on behalf of users. Data used by an application server may be stored on a database server that contains a database management system.

• Web server This is a server that runs a web server program to make web pages available to users. A web server will usually contain both the web server software and the content (“pages”) that are requested by and sent to users’ web browser programs. A web server can also be linked to an application server or database server to permit the display of business information, such as order forms, reports, and so on.

• Database server Also a mainframe, midrange, or small server, a database server runs specialized database management software that controls the storage and processing of large amounts of data that resides in one or more databases.

• Gateway A server that performs some manner of data transformation—for instance, converting messages from one format to another—between two applications.

• File server This computer is used to provide a central location for the storage of commonly used files. File servers may be used by application servers or by a user community.

• Print server In an environment that uses shared printers, a print server is typically used to receive print requests from users or applications and store them temporarily until they are ready to be printed.

• Production server/test server The terms production server and test server denote whether a server supports actual business use (a production server) or is a separate server that can be used to test new programs or configurations (a test server). Most organizations will have at least one test server for every type of production server so that any new programs, configurations, patches, or settings can be tested on a test server, with little or no risk of disrupting actual business operations.

• Thick client A thick client is a user’s computer (of the desktop or laptop variety) that contains a fully functional operating system and one or more application programs. Purists will argue that a thick client is only a thick client if the system contains one or more software application client programs. This is a reasonable distinction between a thick client and a workstation, described later.

• Thin client A thin client is a user’s workstation that contains a minimal operating system and little or no data storage. Thin-client computers are often used in businesses where users run only application programs that can be executed on central servers and data is displayed on the thin client’s screen. A thin client may be a desktop or laptop computer with thin-client software installed, or it may be a specialized computer with no local storage other than flash memory.

• Workstation This is a user’s laptop or desktop computer. For example, a PC running the Windows operating system and using Microsoft Office word processor and spreadsheet programs, a Firefox browser, and Skype messenger would be considered a workstation.

• Virtual desktop This workstation operating system physically resides on a central server that is displayed by and used on a user’s desktop computer.

• Mobile device A user’s smartphone or tablet device is considered a mobile device. Indeed, the lines between laptops and tablets are blurring as larger tablets, particularly with companion keyboards, function like laptops. And, laptop operating systems are appearing on larger tablet devices.

Computer Hardware Architecture

Computers made since the 1960s share common characteristics in their hardware architecture: They have one or more central processing units, a bus (or more than one), main memory, and secondary storage. They also have some means for communicating with other computers or with humans, usually through communications adaptors.

This section describes computer hardware in detail.

Central Processing Unit

The central processing unit, or CPU, is the main hardware component of a computer system. The CPU is the component that executes instructions in computer programs.

Each CPU has an arithmetic logic unit (ALU), a control unit, and a small amount of memory. The memory in a CPU is usually in the form of registers, which are memory locations where arithmetic values are stored.

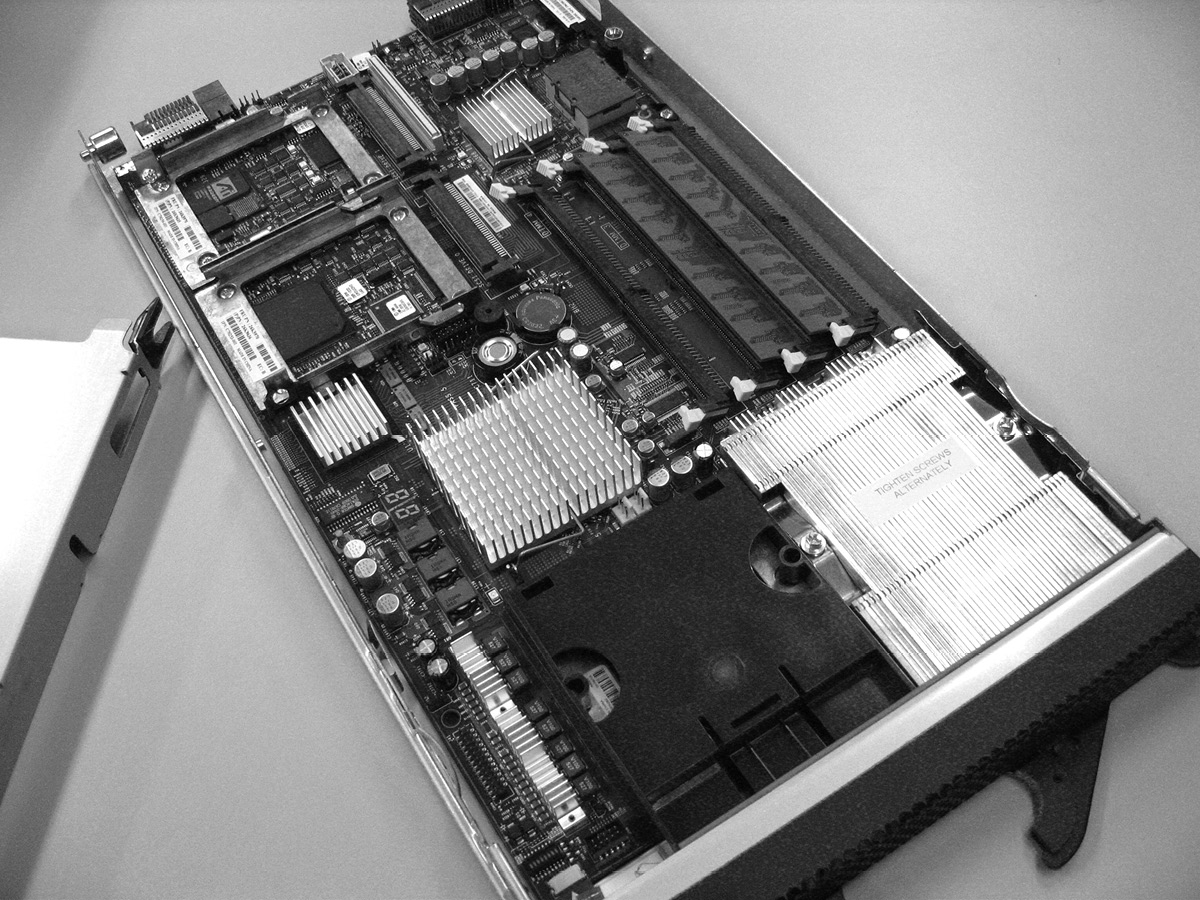

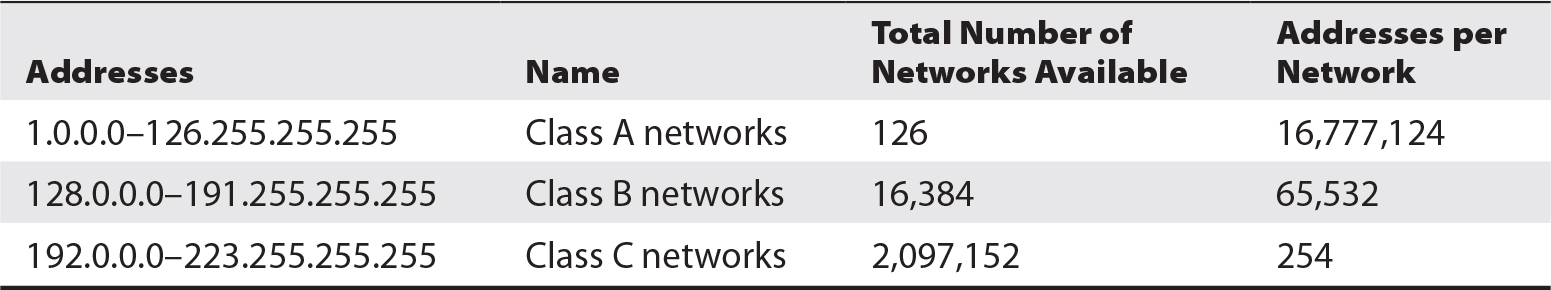

The CPU in modern computers is wholly contained in a single large-scale integration integrated circuit (LSI IC), more commonly known as a microprocessor. A CPU is attached to a computer circuit board (often called a motherboard on a personal computer) by soldering or a plug-in socket. A CPU on a motherboard is shown in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2 A CPU that is plugged into a computer circuit board (Image courtesy of Fir0002/Flagstaffotos)

CPU Architectures A number of architectures dominate the design of CPUs. Two primary architectures that are widely used commercially are

• CISC (complex instruction set computer) This CPU design has a comprehensive instruction set, and many instructions can be performed in a single cycle. This design philosophy claims superior performance over RISC. Well-known CISC CPUs include Intel x86, VAX, PDP-11, Motorola 68000, and System/360.

• RISC (reduced instruction set computer) This CPU design uses a smaller instruction set (meaning fewer instructions in its “vocabulary”), with the idea that a small instruction set will lead to a simpler microprocessor design and better computer performance. Well-known RISC CPUs include Alpha, MIPS, PowerPC, and SPARC. Few of these are produced today, but they are still found in some environments.

Another aspect of CPUs that is often discussed is the power requirements. Typically, the CPUs that are used for laptop computers and mobile devices are known as low-power CPUs, while other CPUs are used in desktop, server, and mainframe systems, where performance and speed are more important considerations than power consumption.

Computer CPU Architectures Early computers had a single CPU. However, it became clear that many computing tasks could be performed more efficiently if computers had more than one CPU to perform them. Some of the ways that computers have implemented CPUs are

• Single CPU In this design, the computer has a single CPU. This simplest design is still prevalent, particularly among small servers and personal computers.

• Multiple CPUs A computer design can accommodate multiple CPUs, from as few as 2 to as many as 128 or more. There are two designs for multi-CPU computers: symmetric and asymmetric. In the symmetric design, all CPUs are equal in terms of how the overall computer’s architecture uses them. In the asymmetric design, one CPU is the “master.” Virtually all multi-CPU computers made today are symmetric.

• Multicore CPUs A change in the design of CPUs themselves has led to multicore CPUs, in which two or more central processors occupy a single CPU chip. The benefit of multicore design is the ability for software code to be executed in parallel, leading to improved performance. Many newer servers and personal computers are equipped with multicore CPUs, and some are equipped with multiple multicore CPUs.

Bus

A bus is an internal component in a computer that provides the means for the computer’s other components to communicate with one another. A computer’s bus connects the CPU with its main and secondary storage as well as to external devices.

Most computers also utilize electrical connectors that permit the addition of small circuit boards that may contain additional memory, a communications device or adaptor (for example, a network adaptor or a modem), a storage controller (for example, a SCSI [Small Computer Systems Interface] or ATA [AT Attachment] disk controller), or an additional CPU.

Several industry standards for computer buses have been developed. Notable standards include

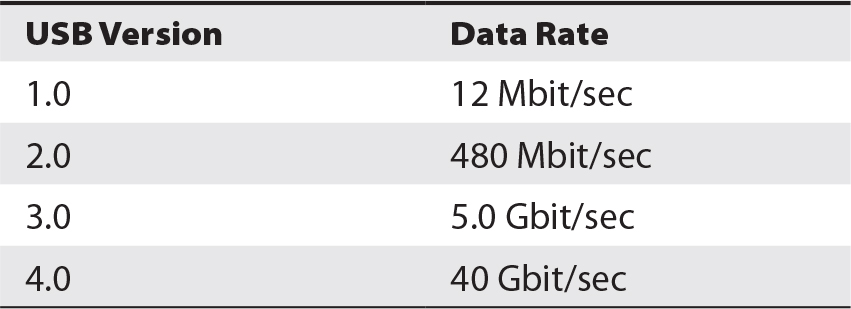

• Universal Serial Bus (USB) This standard is used to connect external peripherals such as external storage devices, printers, and mobile devices. USB operates at data rates up to 40.0 Gbit/sec. USB is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

• Serial ATA (SATA) This standard is used mainly to connect mass storage devices such as hard disk drives, optical drives, and solid-state drives.

• PCI Express (PCIe) This bus standard replaced older standards such as PCI and PCI-X and employs data rates from 250 Mbyte/sec to 128 Gbyte/sec.

• Thunderbolt This hardware interface standard is a combination of PCI Express and DisplayPort (DP) in a single serial signal.

• PC Card Formerly known as PCMCIA, the PC Card bus is prevalent in laptop computers and is commonly used for the addition of specialized communication devices.

• ExpressCard Also developed by the PCMCIA, this bus standard replaces the PC Card standard.

It is not uncommon for a computer to have more than one bus. For instance, many PCs have an additional front-side bus (FSB), which connects the CPU to a memory controller hub, as well as a high-speed graphics bus, a memory bus, and the low pin count (LPC) bus that is used for low-speed peripherals such as parallel and serial ports, keyboard, and mouse.

Main Storage

A computer’s main storage is used for short-term storage of information. Main storage is usually implemented with electronic components such as random access memory (RAM), which is relatively expensive but also relatively fast in terms of accessibility and transfer rate.

A computer uses its main storage for several purposes:

• Operating system The computer’s running operating system uses main storage to store information about running programs, open files, logged-in users, in-use devices, active processes, and so on.

• Buffers Operating systems and programs will set aside a portion of memory as a “scratch pad” that can be used temporarily to store information retrieved from hard disks or information that is being sent to a printer or other device. Buffers are also used by network adaptors to store incoming and outgoing information temporarily.

• Storage of program code Any program that the computer is currently executing will be stored in main storage so that the CPU can quickly access and read any portion of the program as needed. Note that the program in main storage is only a working copy of the program, used by the computer to reference instructions quickly in the program.

• Storage of program variables When a program is being run, it will store intermediate results of calculations and other temporary data. This information is stored in main storage, where the program can quickly reference portions of it as needed.

Main storage is typically volatile. This means that the information stored in main storage should be considered temporary. If electric power were suddenly removed from the computer, the contents of main storage would vanish and would not be easily recovered, if at all.

Different technologies are used in computers for main storage:

• DRAM (dynamic RAM) In the most common form of semiconductor memory, data is stored in capacitors that require periodic refreshing to keep them charged—hence the term dynamic.

• SRAM (static RAM) This form of semiconductor memory does not require periodic refresh cycles like DRAM.

A typical semiconductor memory module is shown in Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3 Typical RAM module for a laptop, workstation, or server (Image courtesy of Sassospicco)

Secondary Storage

Secondary storage is the permanent storage used by a computer system. Unlike primary storage (which is usually implemented in volatile RAM modules), secondary storage is persistent and can last many years.

This type of storage is usually implemented using hard disk drives or solid-state drives ranging in capacity from gigabytes to terabytes.

Secondary storage represents an economic and performance tradeoff from primary storage. It is usually far slower than primary storage, but the unit cost for storage is far less costly. At the time of this writing, the price paid for about 16GB of RAM could also purchase a 2TB hard disk drive, which makes RAM (primary) storage more than 1,000 times more expensive than hard disk (secondary) storage. A hard disk drive from a desktop computer is shown in Figure 5-4.

Figure 5-4 Typical computer hard disk drive (Image courtesy of Robert Jacek Tomczak)

A computer uses secondary storage for several purposes:

• Program storage The programs that the computer executes are contained in secondary storage. When a computer begins to execute a program, it makes a working copy of the program in primary storage.

• Data storage Information read into, created by, or used by computer programs is often stored in secondary storage. Secondary storage is usually used when information is needed for use at a later time.

• Computer operating system The set of programs and device drivers that are used to control and manage the use of the computer is stored in secondary storage.

• Temporary files Many computer programs need to store information for temporary use that may exceed the capacity of main memory. Secondary storage is often used for this purpose. For example, a user wants to print a data file onto a nearby laser printer; software on the computer will transform the stored data file into a format that is used by the laser printer to make a readable copy of the file; this “print file” is stored in secondary storage temporarily until the printer has completed printing the file for the user, and then the file is deleted.

• Virtual memory This is a technique for creating a main memory space that is physically larger than the actual available main memory. Virtual memory (which should not be confused with virtualization) is discussed in detail later in this chapter in the section “Computer Operating Systems.”

While secondary storage is usually implemented with hard disk drives, many newer systems use semiconductor flash memory in solid-state drives (SSDs). Flash is a nonvolatile semiconductor memory that can be rewritten and requires no electric power to preserve stored data.

Although secondary storage technology is persistent and highly reliable, hard disk drives and even SSDs are known to fail from time to time. For this reason, important data in secondary storage is often copied to other storage devices, either on the same computer or on a different computer, or it is copied onto computer backup tapes that are designed to store large amounts of data for long periods at low cost. This practice of data backup is discussed at length in the section “Information Systems Operations,” earlier in this chapter.

Firmware

Firmware is special-purpose storage that is used to store the instructions needed to start a computer system. Typically, firmware consists of low-level computer instructions that are used to control the various hardware components in a computer system and to load and execute components of the operating system from secondary storage. This process of system initialization is known as an initial program load (IPL), or bootstrap (or just “boot”).

Read-only memory (ROM) technology is often used to store a computer’s firmware. Several available ROM technologies are in use, including

• ROM The earliest forms of ROM are considered permanent and can never be modified. The permanency of ROM makes it secure, but it can be difficult to carry out field upgrades. For this reason ROM is not often used.

• PROM (programmable read-only memory) This is also a permanent and unchangeable form of storage. A PROM chip can be programmed only once, and it must be replaced if the firmware needs to be updated.

• EPROM (erasable programmable read-only memory) This type of memory can be written to with a special programming device and then erased and rewritten at a later time. EPROM chips are erased by shining ultraviolet (UV) light through a quartz window on the chip; the quartz window is usually covered with a foil label, although sometimes an EPROM chip does not have a window at all, which effectively makes it a PROM device.

• EEPROM (electrically erasable programmable read-only memory) This is similar to EPROM, except that no UV light source is required to erase and reprogram the EEPROM chip; instead, signals from the computer in which the EEPROM chip is stored can be used to reprogram or update the EEPROM. Thus, EEPROM was one of the first types of firmware that could be updated by the computer on which it was installed.

• Flash This memory is erasable, reprogrammable, and functionally similar to EEPROM, in that the contents of flash memory can be altered by the computer that it is installed in. Flash memory is the technology used in popular portable storage devices such as USB memory devices, Secure Digital (SD) cards, Compact Flash, and Memory Stick.

A well-known use for firmware is the ROM-based BIOS (basic input/output system) on Intel-based personal computers.

I/O and Networking

Regardless of their specific purpose, computers nearly always must have some means for accepting input data from some external source as well as for sending output data to some external destination. Whether this input and output are continuous or infrequent, computers usually have one or more methods for transferring data. These methods include

• Input/output (I/O) devices Most computers have external connectors to permit the attachment of devices such as keyboards, mice, monitors, scanners, printers, and cameras. The electrical signal and connector-type standards include PS/2 (for keyboards and mice), USB, parallel, serial, and Thunderbolt. Some types of computers lack these external connectors; instead, special adaptor cards can be plugged into a computer’s bus connector. Early computers required reprogramming and/or reconfiguration when external devices were connected, but newer computers are designed to recognize when an external device is connected or disconnected and will adjust automatically.

• Networking A computer can be connected to a local or wide area data network. Then, one of a multitude of means for inbound and outbound data transfer can be configured that will use the networking capability. Some computers will have built-in connectors or adaptors, but others will require the addition of internal or external adaptors that plug into bus connectors such as PC Card, ExpressCard, PCI, or USB.

Multicomputer Architectures

Organizations that use several computers have a lot of available choices. Not so long ago, organizations that required several servers would purchase individual server computers. Now there are choices that can help to improve performance and reduce capital, including

• Blade computers This architecture consists of a main chassis component that is equipped with a central power supply, cooling, network, and console connectors, with several slots that are fitted with individual CPU modules. The advantage of blade architecture is the lower-than-usual unit cost for each server module, since it consists of only a circuit board. The costs of power supply, cooling, and so on, are amortized among all of the blades. A typical blade system is shown in Figure 5-5.

Figure 5-5 Blade computer architecture (Image courtesy of Robert Kloosterhuis)

• Grid computing The term grid computing describes a large number of loosely coupled computers that are used to solve a common task. Computers in a grid may be in close proximity to each other or scattered over a wide geographic area. Grid computing is a viable alternative to supercomputers for solving computationally intensive problems.

• Server clusters A cluster is a tightly coupled collection of computers that is used to solve a common task. In a cluster, one or more servers actively perform tasks, while zero or more computers may be in a “standby” state, ready to assume active duty should the need arise. Clusters usually give the appearance of a single computer to the perspective of outside systems. Clusters usually operate in one of two modes: active-active and active-passive. In active-active mode, all servers perform tasks; in active-passive mode, some servers are in a standby state, waiting to become active in an event called a failover, which usually occurs when one of the active servers has become incapacitated.

These options give organizations the freedom to develop a computer architecture that will meet their needs in terms of performance, availability, flexibility, and cost.

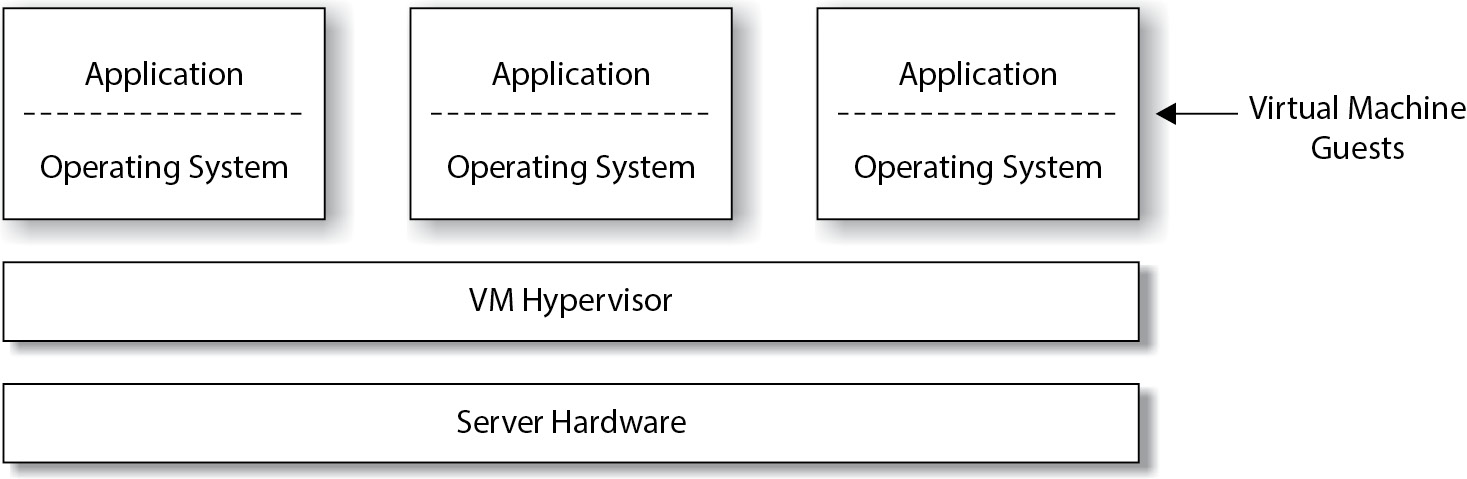

Virtualization Architectures

Virtualization refers to the set of technologies that permits two or more running operating systems (of the same type or different types) to reside on a single physical computer. Virtualization technology enables organizations to use computing resources more efficiently.

Before I explain the benefits of virtualization, I should first state one of the principles of computer infrastructure management. It is a sound practice to use a server for one single purpose. Using a single server for multiple purposes can introduce a number of problems, including

• Tools or applications that reside on a single computer may interfere with one another.

• Tools or applications that reside on a single computer may interact with each other or compete for common resources.

• A tool or application on a server could, although rarely, cause the entire server to stop running; on a server with multiple tools or applications, this could cause the other tools and applications to stop functioning.

Prior to virtualization, the most stable configuration for running many applications and tools was to run each on a separate server. This would, however, result in a highly inefficient use of computers and of capital, as most computers with a single operating system spend much of their time in an idle state.

Virtualization permits IT departments to run many applications or tools on a single physical server, each within its own respective operating system, thereby making more efficient use of computers (not to mention electric power and data center space). Virtualization software emulates computer hardware so that an operating system running in a virtualized environment does not know that it is actually running on a virtual machine. Virtualization software, known as a hypervisor, includes resource allocation configuration settings so that each guest (a running operating system) will have a specific amount of memory, hard disk space, and other peripherals available for its use. Virtualization also facilitates the sharing of peripheral devices such as network connectors so that many guests can use an individual network connector, although each will have its own unique IP address.

Virtualization is the basis of cloud-based Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) services such as Amazon AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure.

Virtualization software provides security by isolating each running operating system and preventing it from accessing or interfering with others. This is similar to the concept of process isolation within a running operating system, where a process is not permitted to access resources used by other processes.

A server with running virtual machines is depicted in Figure 5-6.

Figure 5-6 Virtualization

Many security issues need to be considered in a virtualization environment, including

• Access control Access to virtualization management and monitoring functions should be restricted to those personnel who require it.

• Resource allocation A virtualization environment needs to be carefully configured so that each virtual machine is given the resources it requires to function correctly and perform adequately.

• Logging and monitoring Virtual environments need to be carefully monitored so that any sign of security compromise will be quickly recognized and acted on.

• Hardening Virtual environments need to be configured so that only necessary services and features are enabled, and all unnecessary services and features are either disabled or removed.

• Vulnerability management Virtualization environments need to be monitored as closely as operating systems and other software so that the IT organization is aware of newly discovered security vulnerabilities and available patches.

Hardware Maintenance

In comparison to computer hardware systems that were manufactured through the 1980s, today’s computer hardware requires little or no preventive or periodic maintenance. And with today’s popular cloud-based computing, some organizations have little or no data center hardware to maintain at all.

Computer hardware maintenance is limited to periodic checks to ensure that the computer is free of dirt and moisture. From time to time, a systems engineer will need to open a computer system cabinet and inspect it for accumulation of dust and dirt, and he or she may need to remove this debris with a vacuum cleaner or filtered compressed air. Depending on the cleanliness of the surrounding environment, inspection and cleaning may be needed as often as every few months or as seldom as every few years.

Maintenance may also be carried out by third-party service organizations that specialize in computer maintenance.

When it is required, hardware maintenance is an activity that should be monitored. Qualified service organizations should be hired to perform maintenance at appropriate intervals. If periodic maintenance is required, management should establish a service availability plan that includes planned downtime when such operations take place.

Automated hardware monitoring tools can provide information that will help determine whether maintenance is needed. Automated monitoring is discussed in the next section.

Hardware Monitoring

Automated hardware monitoring tools can be used to keep a continuous watch on the health and utilization of server and network hardware. In an environment with many servers, this capability can be centralized so that the health of many servers and network devices can be monitored using a single monitoring program.

Hardware monitoring capabilities may vary among different makes of computer systems, but can include any or all of the following:

• CPU Monitoring will indicate whether the system’s CPU is operating properly and whether its temperature is within normal range.

• Power supply Monitoring will show whether the power supply is operating properly, including input voltage, output voltage and current, cooling fans, and temperature.

• Internal components Monitoring will specify whether other internal components such as storage devices, memory, chipsets, controllers, adaptors, and cooling fans are operating properly and within normal temperature ranges.

• Resource utilization Monitoring will measure the amount of resources in use, including CPU, memory, disk storage, and network utilization.

• Asset management Many monitoring systems can track the assets that are present in the environment, giving management an electronic asset inventory capability.

• External environment Monitoring is usually considered incomplete unless the surrounding environment is also monitored. This usually includes temperature, humidity, the presence of water, and vibration in locales where earthquakes are common. Monitoring can also include video surveillance and access door alarms.

Centralized monitoring environments typically utilize the local area network for transmitting information from systems to a central console. Many monitoring consoles have the ability to send alert messages to the personnel who manage the systems being monitored. Often, reports can show monitoring statistics over time so that personnel can identify trends that could be indications of impending failure.

Public cloud IaaS vendors perform hardware monitoring on behalf of their customers.

Information Systems Architecture and Software

This section discusses computer operating systems, data communications, file systems, database management systems, media management systems, and utility software.

Computer Operating Systems

Computer operating systems (which are generally known as operating systems, or OSs) are large, general-purpose programs that are used to control computer hardware and facilitate the use of software applications. Operating systems perform the following functions:

• Access to peripheral devices The operating system controls and manages access to all devices and adaptors that are connected to the computer. This includes storage devices, display devices, and communications adaptors.

• Storage management The operating system provides for the orderly storage of information on storage hardware. For example, operating systems provide file system management for the storage of files and directories on SSDs or hard drives.

• Process management Operating systems facilitate the existence of multiple processes, some of which will be computer applications and tools. Operating systems ensure that each process has private memory space and is protected from interference and eavesdropping by other processes.

• Resource allocation Operating systems facilitate the sharing of resources on a computer such as memory, communications, and display devices.

• Communication Operating systems facilitate communications with users via peripheral devices and also with other computers through networking. Operating systems typically have drivers and tools to facilitate network communications.

• Security Operating systems restrict access to protected resources through process, user, and device authentication.

Examples of popular operating systems include Linux, Solaris, macOS, Android, iOS, Chrome OS, and Microsoft Windows.

The traditional context of the relationship between operating systems and computer hardware is this: one copy of a computer operating system runs on a computer at any given time. Virtualization, however, has changed all of that. Virtualization is discussed earlier in this chapter.

Server Clustering

Using special software, a group of two or more computers can be configured to operate as a cluster. This means that the group of computers will appear as a single computer for the purpose of providing services. Within the cluster, one computer will be active and the other computer(s) will be in passive mode; if the active computer should experience a hardware or software failure and crash, the passive computer(s) will transition to active mode and continue to provide service. This is known as active-passive mode. The transition is called a failover.