APPENDIX B

Popular Methodologies, Frameworks, and Guidance

This appendix discusses the following topics:

• Common terms and concepts utilized in methodologies, frameworks, and guidance

• Demystifying the various resources available and their value to the CISA

Are you getting ready to develop, document, or audit IT controls? Several methodologies, frameworks, and guides contain detailed information on processes, control objectives, and controls that may assist you in your efforts. This appendix is dedicated to helping you make sense of these available resources and the terminology used within each of them.

The appendix is divided into two main sections. The first section focuses on common terms and concepts, while the second section describes the various methodologies, frameworks, and guides available and provides background information, high points, and a summary of why the resource may be helpful to a CISA-certified professional.

If you are reading this for the first time, it is recommended that you pay close attention to the first section, “Common Terms and Concepts,” which provides you with a foundation from which to view the resources. Once you are familiar with the terminology, you can skip to the second section, “Frameworks, Methodologies, and Guidance,” and find the resources that most directly apply to you and your organization’s objectives. A table is provided at the end of the appendix as guidance for which frameworks may be most relevant to you.

Common Terms and Concepts

This section was created with the intention that it be used for reference when you are working with one of the frameworks discussed in the second section (or another that is not discussed in this book). At some point, you may hear someone refer to one of the frameworks or methodologies described in this appendix or find yourself wondering if a particular framework or methodology may be valuable to you.

When looking for resources, consider the level and type of information you are looking for. Are you looking for information on implementing processes, control objective statements, or detailed guidance on specific controls? Are you developing a set of general IT controls, assessing a process, or writing particular policies and standards? Each of these activities may be covered in complementary resources; however, if you are in a time crunch, it is recommended that you first determine what you are looking for. Using the following common terms and concepts should help you to narrow down the type of information you are on an adventure to find.

Governance

Enterprise governance (or corporate governance) is defined as the responsibilities and practices followed by executive management and the board of directors to ensure that the enterprise’s strategic goals and objectives are met, risks are managed, and resources are used responsibly.

ISACA defines governance as follows: Ensures that stakeholder needs, conditions and options are evaluated to determine balanced, agreed-on enterprise objectives to be achieved; setting direction through prioritization and decision making; and monitoring performance and compliance against agreed-on direction and objectives.

Examples of enterprise governance practices would be that of senior management providing direction and oversight, clearly identifying roles and responsibilities, coordinating initiatives, managing resources, identifying and assessing risks, approving budgets, and enforcing compliance. Integrity, ethical behavior, risk management, transparency, and accountability are just a few principles of enterprise governance. Enterprise governance is critical for increasing investor confidence and ensuring compliance and profitability.

IT governance is a vital part of enterprise governance and aims to ensure that IT is meeting strategic goals and managing risks, and that IT investments are generating business value. IT governance is the foundation for all IT strategic and tactical activities. It helps ensure that strategic goals and objectives are set and measured against; activities, resources, and investments are managed and prioritized; and IT risks are identified and managed.

The IT Governance Institute (ITGI; a part of ISACA) has developed an IT governance framework that focuses on strategic alignment of IT with the business strategy, value delivery of IT, IT resource management, IT performance management, and IT risk management. You can find more information on this online in the ITGI publication, Board Briefing on IT Governance: 2nd Edition.

Although governance is the focus of the Certified in the Governance of Enterprise IT (CGEIT) certification, it is important to understand that IT governance is the foundation of IT management and may affect which processes and controls are prioritized or assessed at any given time.

Goals, Objectives, and Strategies

Often, the terms “goals” and “objectives” are used synonymously in documentation and planning. Both are used to describe a desired end state, or what an organization intends to achieve. Strategies are the means, or actions, by which an organization intends to realize these goals.

One of the most popular terms in the IS world and control and process frameworks is “objective.” Keep in mind that an objective is what the enterprise is trying to achieve or the expected result of an activity. It is always set within a context. For example, the COBIT framework describes several IT processes and related objectives. In addition, the framework describes specific control objectives. COBIT is not an objective framework, but aligning IT processes to COBIT may help to achieve objectives.

Business objectives, process objectives, and control objectives are different from each other. Business objectives are higher level statements that guide the organization. Process objectives describe what the process activities intend to achieve, while control objectives describe what the implemented controls are trying to achieve or risks the controls are attempting to mitigate. It is important to understand that the concept of objectives is widely used, and they need to be kept in proper context. Some examples of different objectives are shown in Table B-1.

Table B-1 Examples of Objectives

Detailed definitions of goals and objectives are provided in the Business Motivation Model, which is published by the Business Rules Group. In this publication, goals are seen as general statements that are ongoing, longer term, and qualitative, whereas objectives are intended to be more specific, shorter term, time-specific, and quantitative. In the same model, strategies are said to be the activities that are planned to channel efforts toward goals. The model provides an entire framework for developing mission, vision, goal, objective, strategy, tactic, and directive statements, just to name a few, for an organization.

Processes

Simply stated, processes are used to manage and organize a set of activities and to help ensure that organizational goals are being met.

Each process represents a series of steps or activities designed to take one or more inputs and create some sort of output(s) that delivers a service or product to meet specific expectations or desired objectives/goals for a particular group of customers. Usually a process consists of one or more written procedures that describe the actions that people (and/or systems) perform. In summary, processes are put into place to guide how an organization does work in order to produce value for customers.

Example Process

An example of a process would be the assessment and management of IT risks. The process would represent a set of activities and may look like this:

Determine the Context -> Identify Risks -> Assess Risks -> Prioritize -> Respond -> Monitor

• Potential inputs: Internal and external audit reports, business stakeholder interviews, vendor assessments, vulnerability scans

• Potential outputs: Risk registers, risk reports, mitigation tracking reports

• What business goal does this process meet? Manage IT-related business risks

Several frameworks describe the various IT processes, interdependencies, inputs, outputs, and metrics, most notably COBIT and IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL). These frameworks are discussed later in this appendix. For more detailed information on business process design or improvement, you may want to research business process modeling or methodologies and toolkits on the Web, such as RummlerBrache (https://www.rummlerbrache.com/toolkit).

Capability Maturity Models

Initially developed by the Carnegie Mellon Software Engineering Institute as a software evaluation model, capability maturity models (CMMs) are used in several frameworks to determine and describe incremental maturity levels of business process and engineering capabilities.

The maturity of a process or system is rated on a scale from 0 to 5, with a level of 0 referring to a nonexistent process and a 5 equating to the greatest maturity in capability. The ideal maturity rating differs for each organization.

CMMs can be used to assist organizations with developing process maturity baselines, benchmarking, prioritizing activities, and defining improvement. They can be useful in conjunction with any process framework adopted. An example of a CMM is that which is used in the COBIT framework to describe the maturity of COBIT-identified processes.

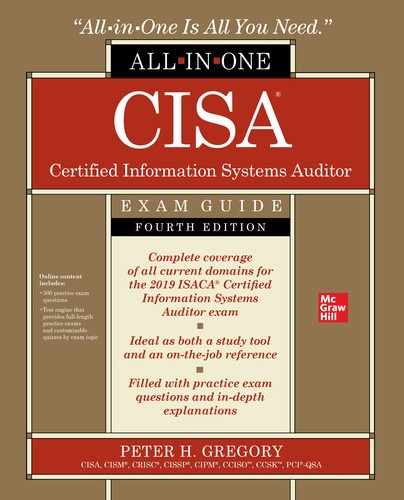

Table B-2 provides an example of a maturity model and the ratings used to measure those processes outlined in COBIT. Figure B-1 represents how this maturity model can be used to show current and future desirable states and for benchmarking against competitors or industry standards.

Figure B-1 Rating scale for process maturity

Table B-2 Example Process Maturity Model

Controls

Controls are the means by which management establishes and measures processes by which organizational objectives are achieved. Controls may be established to improve effectiveness, efficiency, integrity of operations, and compliance with laws and regulations.

Frameworks may represent collections of controls that work together to achieve an entire range of an organization’s objectives. Because many organizations operate similarly, standard frameworks of controls have been established, which can be adopted in whole or in part. Some of these frameworks are discussed later in this appendix.

There are many ways in which the frameworks discuss controls:

• Internal control This aggregate system is put into place in an organization to provide management with reasonable assurance that objectives are met. It refers to the many control objectives and related control activities in place to meet business objectives.

• Control objectives Control objectives ensure that business objectives are achieved and that undesirable events are prevented or detected and corrected.

• Control activities/controls These are the specific policies, procedures, and activities in place to meet the control objectives. Controls may be put into place to help prevent or detect and correct undesired events in the organization.

There are two main types of controls: general controls and application controls. General controls support the functioning of the application controls—both are needed for complete and accurate information processing. General controls apply to all systems and the computing environment, while application controls handle application processing.

Some examples of IT general controls include

• Access controls

• Change management

• Security controls

• Incident management

• System development life cycle (SDLC)

• Source code and versioning controls

• Disaster recovery and business continuity plans

• Monitoring and logging

• Event management

Examples of application controls include

• Authentication

• Authorization

• Completeness checks

• Validation checks

• Input controls

• Output controls

• Identification/access controls

Tips for identifying and documenting controls include the following:

• When looking at processes, define potential risks/points of failure (that is, what could go wrong in a process, or what would happen if this process fails?).

• Identify controls and examine whether they operate at a level of granularity that make them adequate in preventing or detecting errors and irregularities.

• Check to see if the control’s strength is commensurate with the level of risk the control is mitigating.

• The cost of implementing a control should not exceed the expected benefit.

• Well-designed internal controls can lead to operating efficiencies and sometimes reduction in costs and risks.

• Effective controls reduce risk, increase the likelihood of value delivery, and improve efficiency because of fewer errors and a consistent management approach.

• Auditors are responsible for the independent evaluation of internal controls and whether they are adequate.

The Deming Cycle

Dr. W. Edwards Deming developed a four-step quality control process known around the world as the Deming Cycle, PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) or PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act). The steps in the Deming Cycle are

• Plan Establish objectives to align with desired outcomes and predict results.

• Do Execute the plan in a controlled manner.

• Study/Check Check the results on a regular basis and compare with expectations.

• Act Analyze the results and take corrective actions.

Many of the frameworks described in this appendix are based on this concept, which supports continuous quality monitoring and business process improvement. Each framework defines the set of processes and how they support the different steps. For example, in the project management frameworks, specific processes are necessary for properly planning, executing, and monitoring a project. Although each of the processes is unique, they collectively contribute to continuous quality and improvement.

Projects

Virtually all technology professionals participate in projects. Projects are organized activities intended to bring about a new process or system or a change to a process or system. Projects are generally thought of as unique, one-time, nonrepeated efforts. Examples of projects include

• Design and development of a new software application

• Migration of an application from Windows to Linux

• Development of a new accounts payable process

Most of the time, formal project management techniques will be implemented in conjunction with software or system acquisition and implementation processes.

Here are a few things to keep in mind about projects and project management:

• Projects are a means to organize activities that are not addressed within normal operational limits. Often, projects are used as a means to achieve an organization’s strategic objectives.

• Project management consists of a set of processes.

• Projects are similar to operations in that they are performed by people, constrained by resources, planned, executed, and controlled.

• Operations are ongoing, while projects are temporary and unique.

• Project and operational objectives are different. Once project objectives are met, the project is considered complete. Operational objectives are ongoing and are in place to sustain business activities and goals. Once operational objectives are met, new ones are adopted and things keep moving forward.

• Controls exist in projects. Examples include comparing actual with planned budgets and time, analysis of variances, assessment of trends to effect process improvements, evaluation of alternatives, and recommendation of corrective actions.

There are frameworks available to assist you, should you be responsible for planning or managing a project. In addition, the information provided within these frameworks may be helpful if you are responsible for auditing the SDLC or assessing any related project documentation.

Frameworks, Methodologies, and Guidance

Creating appropriate processes and controls can be daunting. This is where frameworks, methodologies, and guidance can become valuable. Many internationally recognized organizations have already conducted the research and documented their conclusions, resulting in the publication of several high-quality frameworks and methodologies.

Before re-creating the wheel, consider utilizing these existing resources as a basis for your process and control discussions, audits, or project planning. Many of the documents available today are quite comprehensive and can save you a great deal of time and heartache. They often outline key processes and controls that can be implemented to meet specific business goals and objectives.

The following sections identify the most renowned and respected resources with regard to managing IT governance, controls, processes, information security, and projects. The background and high points of each resource is described, as well as how each may be useful for a CISA-certified professional.

Keep in mind that the following resources are merely structures of ideas formulated to solve or address complex issues, or outline possible courses of action to represent a preferred and reliable approach to an idea. They are not intended to be the sole source for your efforts.

Business Model for Information Security (BMIS)

Based on research conducted by the Institute for Critical Information Infrastructure Protection at the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business, the Business Model for Information Security (BMIS) was developed in 2009 by ISACA mainly for use by security professionals. Primarily built on a foundation of systems theory, the business model is unique in that it tackles security issues from a systems perspective. The model is not intended to replace security program best practices but should be used to integrate security program components into one complete functioning system.

BMIS Highlights

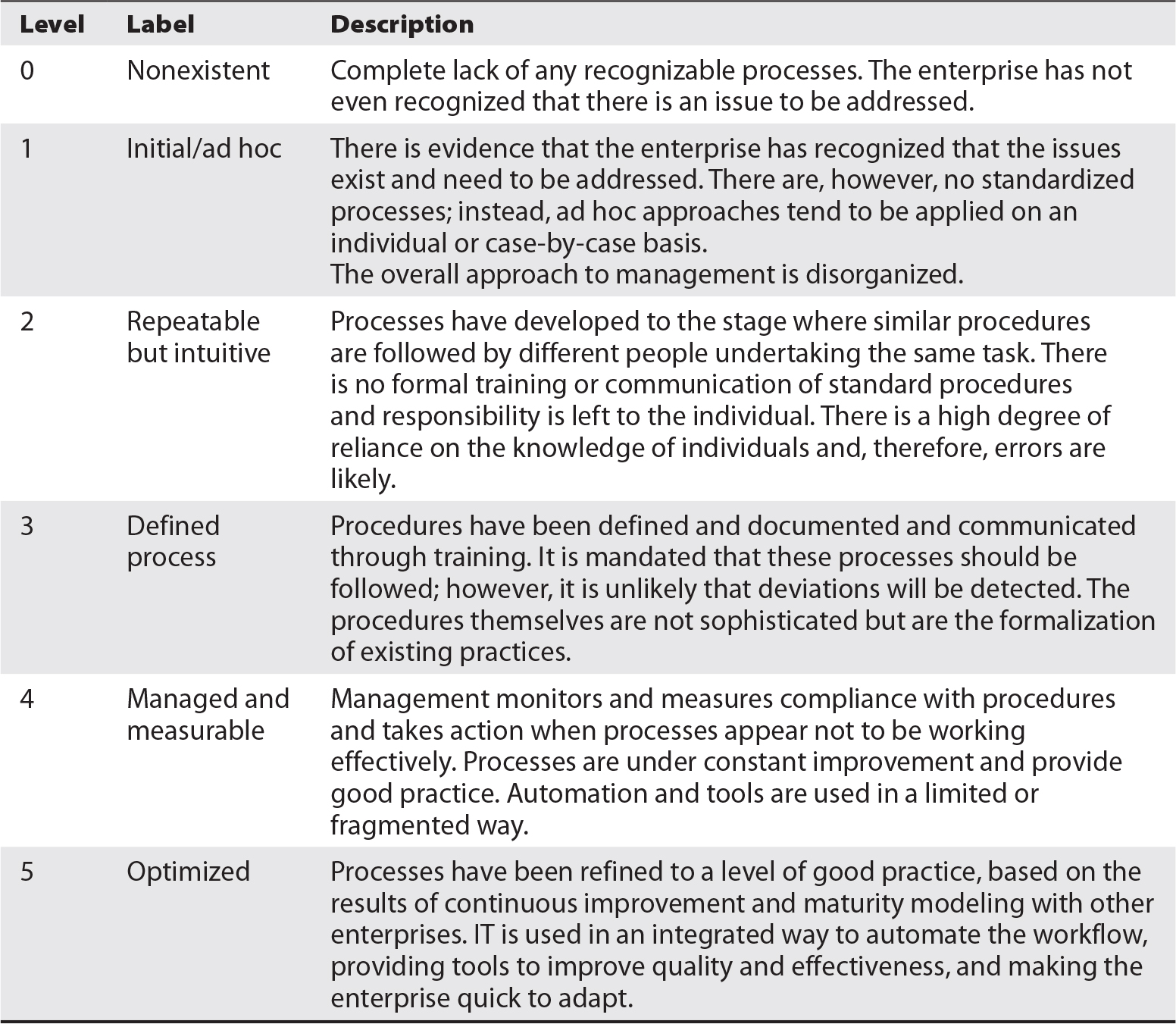

BMIS is a three-dimensional model, similar to a pyramid, composed of four elements and six dynamic connections, shown in Figure B-2. The model requires balance and can be distorted should one of the elements not be addressed or appropriately managed. Using a business-oriented approach, the model explores the elements and the relationships between them in great detail.

Figure B-2 The Business Model for Information Security

The model’s primary objective is to create an “intentional” security culture through instituting awareness campaigns, developing cross-functional teams (such as risk councils and steering committees), and obtaining management support and commitment. In addition, this intentional culture should aim to fulfill enterprise governance needs by ensuring the alignment of information security objectives to business objectives; instituting a risk-based approach to controls; instilling balance among the organization, people, process, and technology; and aligning security strategies across the enterprise.

BMIS Value for the CISA

The model is useful for senior executives, information security managers, those responsible for managing business risk, and those responsible for designing, implementing, monitoring, or improving an Information Security Management System (ISMS).

In addition, the model is useful if you are looking for ways to align information security to privacy, risk, physical security, and compliance. It also provides a common language to talk to business management about information security.

COSO Internal Control – Integrated Framework

Originally authored in 1992 by Coopers & Lybrand (now PricewaterhouseCoopers), and updated in 2013, for the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), the COSO Internal Control – Integrated Framework is by far one of the most fundamental frameworks available to an IS auditor. It defines internal control and provides guidance for assessing and improving internal control systems. The term “internal control” stems from senior management’s need to “control” and be “in control.”

Formed in 1985, COSO is a private-sector group in the United States sponsored by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), American Accounting Association (AAA), Financial Executives International (FEI), The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA), and The Institute of Management Accountants (IMA).

It is highly recommended that those who are CISA-certified take the time to become familiar with this framework. It is the basis of internal control descriptions and is fundamental to understanding, assessing, and making improvements to an internal control environment successfully.

COSO Highlights

The COSO framework is composed of four volumes, the framework volume being the most widely used, which contains these sections:

• Executive summary

• Framework

• Tools for assessing control effectiveness

• Approaches and examples for internal controls

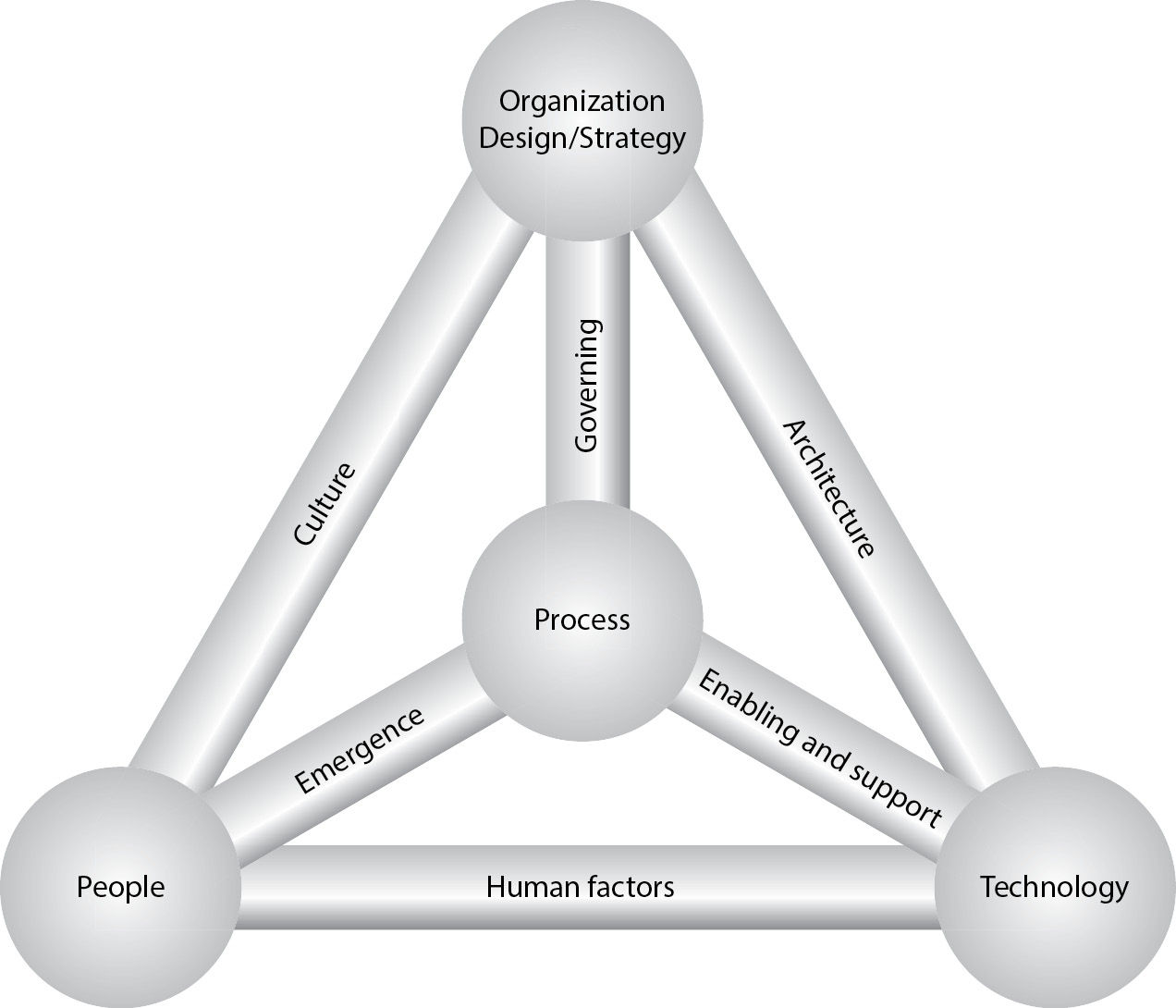

The framework and appendices focus on one main concept and five interrelated internal control components that compose what many call the COSO “cube” (see Figure B-3).

Figure B-3 The COSO cube

The COSO cube consists of three dimensions:

• Objectives

• Components

• Business units/areas

The main concept of the COSO framework is that internal control is a process, affected by people, designed to provide reasonable assurance that the entity is meeting its objectives:

• Process A process is not one event, but a series of activities that are integrated in an organization.

• Affected by people People across the organization establish objectives and ensure that controls are in place. At the same time, internal controls affect people’s actions.

• Reasonable assurance Internal control can provide only reasonable, not absolute, assurance that the organization is meeting its objectives, because of limitations such as human judgment and error, potential for controls to be circumvented through collusion, or controls being overridden by management.

• Objectives Internal control helps organizations meet the following objectives, all of which are separate but may overlap:

• Effectiveness and efficiency of operations: performance, profitability goals, safeguarding assets

• Reliability of financial reporting: prepare reliable financial reports while preventing financial misstatements

• Compliance with applicable laws and regulations

In addition, the framework describes the following five interrelated components of internal control:

• Control environment This is the foundation of how the business operates, where individuals know that they are to conduct activities and carry out control responsibilities. A solid control environment is exhibited by integrity and ethical values, commitment to competence, dedicated board and audit committees, management’s philosophy and operating style, the organizational structure, assignment of authority and responsibility, and human resources policies and practices.

• Risk assessment The organization should establish mechanisms to identify, assess, and manage the risks to objectives. This component is evident through the establishment of entity-wide and activity-level objectives, risks identified, and how well the organization manages change.

• Control activities Control policies and procedures are in place to ensure that the actions and controls needed to ensure objectives are met and that mitigating activities are carried out. Examples of control activities include approvals, authorizations, security of assets, segregation of duties, top-level reviews, information processing, physical controls, and performance indicators. Success in this area occurs when control activities are linked to meeting objectives and are deemed necessary to mitigate risks in meeting the objectives.

• Information and communication Information pertaining to control activities should flow through the organization so that management knows whether its objectives are being met. It should be in a form and time frame that ensures that people can carry out responses. Information and communication can be considered successful when they are flowing up to management and down to employees in sufficient detail and in a timely manner, when established communication channels exist internally and with external parties, and when management is open and receptive to suggestions.

• Monitoring activities The process should be monitored and modified as necessary through ongoing monitoring activities, separate evaluations, or a combination of both. Control deficiencies should be reported upstream, with important issues being communicated to the board or senior management. Management needs information to ensure that the internal control system is effective, to identify whether new risks have developed, and to determine if internal controls are still relevant. Monitoring is considered successful when it is ongoing and built into operations, separate evaluations are conducted, and deficiencies are reported in an open and timely basis.

When is an internal control system effective? When you’ve assessed and concluded that the five components listed previously are functioning successfully and the organization’s objectives are being met:

• The board of directors and management understand operational objectives and whether they are being achieved.

• Financial reporting is prepared reliably.

• Laws and regulations are being complied with.

Making Sense of the COSO Cube

Each organization has three main types of objectives that span across all divisions and groups. To ensure that these objectives are met, the five interrelated internal control components must be in place. There must be a solid control environment, with risk assessments to confirm that adequate control activities are in place to mitigate risk and that risks to objectives are properly managed. In addition, information regarding risk, activities, and deficiencies should be reported through the organization and responded to in a timely manner. Evaluation and monitoring of activities to ensure that objectives are met should occur on a continual basis, with corrective actions taken when necessary.

COSO Value for the CISA

COSO is the basis for the majority of all internal control discussions and process and control frameworks. Whether you are educating others on internal controls, as outlined in the CISA Professional Code of Ethics, or evaluating or testing internal control effectiveness, COSO provides a foundation with which the CISA should be familiar. COSO is a great source for definitions and explanations. Due to the enterprise basis by which COSO has been developed, it is highly recommended that it serve as the foundation, and other frameworks, such as COBIT, ISO/IEC 27001/2, NIST 800-53, and ITIL, build upon this knowledge. Other COSO guidance includes ongoing updates to the Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework and the Internal Control – Integrated Framework, such as COSO in the Cyber Age, which provides guidance for utilizing frameworks to evaluate cybersecurity.

COBIT

The COBIT framework was created in 1992 by ISACA and the IT Governance Institute (ITGI). In 1996, the first edition of COBIT was released to the public. Version 5 was released in April 2012 and COBIT 2019, the most current version, was released in 2018. COBIT aligns with and meets COSO internal control requirements.

COBIT was developed to assist companies in maximizing the benefits derived through the strategic use of IT. Broad, yet detailed, the COBIT framework was designed for use by managers, auditors, and IT personnel and contains IT governance guidance. The framework aligns IT goals with general business goals; contains a comprehensive list of IT processes; and links related control objectives, metrics, and roles and responsibilities for carrying out process activities.

COBIT Highlights

The COBIT framework is composed of six elements, covered in multiple documents:

• Executive summary

• Governance and control framework

• Control objectives

• Management guidelines

• Implementation guide

• IT assurance guide

The framework is complex and requires dedicated individuals to implement and compile the elements. The framework is based upon the notion of strong IT governance, stressing alignment to business strategy and goals.

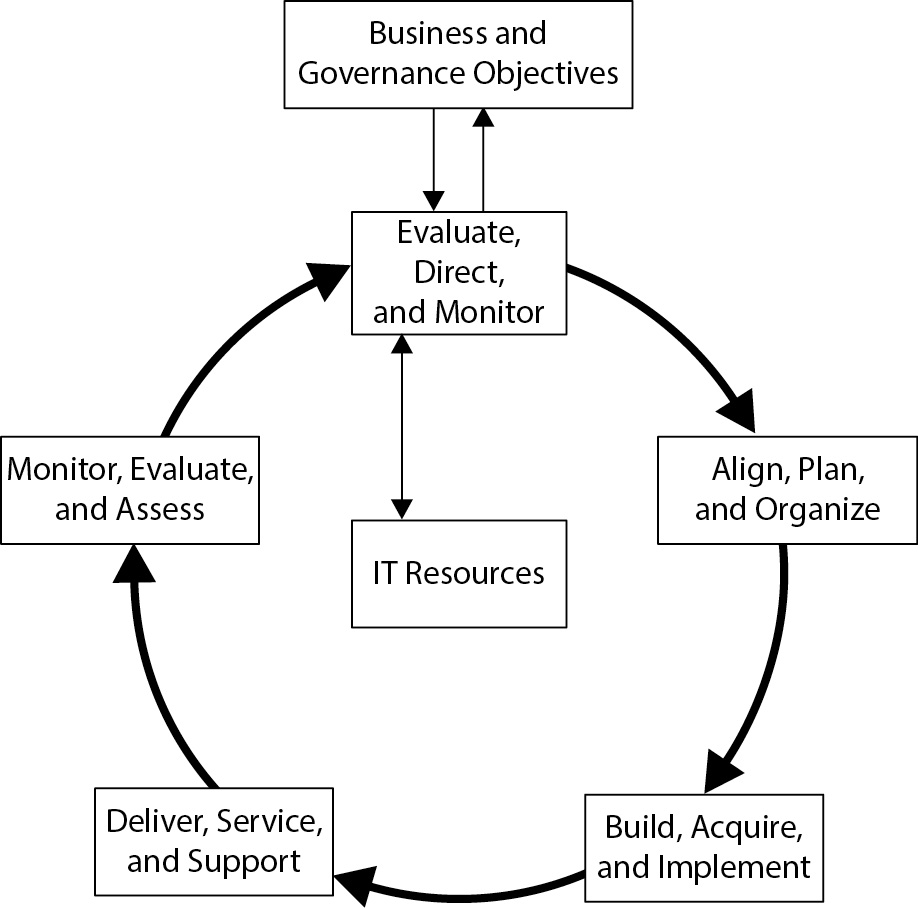

As with many frameworks, COBIT is based on the Deming Cycle, with 37 IT processes falling into the following five domains:

• Evaluate, Direct, and Monitor (EDM) Processes in this domain are focused on the overall governance of IT.

• Align, Plan, and Organize (APO) Processes in this domain are dedicated to ensuring that IT goals are strategically aligned with the business strategy and goals.

• Build, Acquire, and Implement (BAI) Processes for acquiring software, personnel, and external resources are covered in this domain, along with those processes needed to implement them.

• Deliver, Service, and Support (DSS) Operational managers can focus on these processes for delivering and supporting the resources utilized, including people, infrastructure, software, and third-party services.

• Monitor, Evaluate, and Assess (MEA) Processes ensure that the outcome is delivered and measured against initial expectations and that deviations are investigated and result in corrective actions.

Figure B-4 provides an overview of the COBIT framework. Note how the 37 process categories coincide with a cycle similar to that of the Deming Cycle (Plan-Do-Check-Act).

Figure B-4 The COBIT 2019 framework

Each process is outlined in the framework and details the associated process objectives, control objectives, roles and responsibilities charts, metrics, and process maturity levels.

COBIT Value for the CISA

The COBIT framework is ideal for those looking for a comprehensive framework to outline how IT goals and processes align with business goals, what processes IT should consider implementing, and related control objectives.

COBIT nicely ties general business goals to IT goals with the use of a balanced scorecard. This enables you to see which IT processes are key in supporting specific IT goals and, ultimately, business goals.

For personnel who are implementing or evaluating a process, the COBIT framework provides an overview of general processes utilized to manage IT. Each process in COBIT includes key activities, control objectives, and metrics that should be in place.

COBIT is one of the most comprehensive and widely used frameworks available, which equates to the development of additional research and documentation being available. See the ISACA web site for an extensive line of COBIT and COBIT-related documents. Not only will you find COBIT translated into more than eight foreign languages, you also will find documents mapping popular frameworks with COBIT, a “quickstart” guide to implementing COBIT, and guides for utilizing COBIT within various focus areas (such as security, Sarbanes-Oxley, IT assurance, and service management).

GTAG

Global Technology Audit Guides (GTAG) represents a series of documents developed by the IIA to help organizations with their IT control framework and audit practices. The guides are developed to assist with describing the importance of IT controls as part of the internal controls environment, establishing the roles and responsibilities required for ensuring controls are in place and assessed, and addressing the risks inherent in using and managing IT. The first GTAG guide was published in 2005 and it was updated in 2012.

Several groups aid in the development of the guides, including an advanced technology committee and other professional organizations (ACIPA, FEI, ISSA, Sans Institute, and Carnegie Mellon SEI).

The GTAG guides are geared toward chief audit executives and other executives needing a high-level overview of the latest technology issues and how they affect the organization, the associated risks, and necessary IT controls.

GTAG Highlights

Several GTAG guides have been published and are available through the IIA. At the time of writing, these guides are

• Data Analysis Technologies (Previously GTAG 16)

• Developing the IT Audit Plan (Previously GTAG 11)

• Fraud Prevention and Detection in an Automated World (Previously GTAG 13)

• Identity and Access Management (Previously GTAG 9)

• Information Technology Outsourcing, 2nd Edition (Previously GTAG 7)

• Information Technology Risk and Controls, 2nd Edition (Previously GTAG 1)

• Management of IT Auditing, 2nd Edition (Previously GTAG 4)

• Understanding and Auditing Big Data

GTAG Value for the CISA

Although GTAG documents primarily target the chief audit executive, IS auditors can utilize them to learn more about controls and for assistance with describing IT risk and controls in executive terms.

GTAG can be downloaded by IIA members free of charge, or for a reasonable price for nonmembers, from the IIA web site. Hard copies of some guides can also be purchased should you choose to add the publications to your library.

GAIT

The Guide to the Assessment of IT Risk (GAIT) was developed by the IIA to assist with IT general-control risk assessment and scoping for Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 (SOX 404). The GAIT series provides guidance on assessing risk to the financial statements and key controls that could be implemented within the business and IT sectors, including IT general controls (IT GC) and automated controls.

GAIT Highlights

The methodology provides guidance on identifying risks and related controls needed to protect financially significant applications and related processes and data.

Currently, three practice guides are available:

• GAIT Methodology uses a risk-based approach to scope IT GCs

• GAIT for IT General Controls Deficiency Assessment (GAIT 2)

• GAIT for Business and IT Risk (GAIT-R)

GAIT does not specify key controls, but it does describe the IT GC processes and control objectives that should be addressed.

GAIT is based on four principles, according to the IIA:

• The identification of risks and related controls in IT general control processes (for example, in change management, deployment, access security, and operations) should be a continuation of the top-down and risk-based approach used to identify significant accounts, risks to those accounts, and key controls in the business processes.

• The IT general control process risks that need to be identified are those that affect critical IT functionality in financially significant applications and related data.

• The IT general control process risks that need to be identified exist in processes and at various IT layers: application program code, databases, operating systems, and networks.

• Risks in IT general control processes are mitigated by the achievement of IT control objectives, not individual controls.

GAIT Value for the CISA

If you are asked to scope and identify key IT general controls for SOX 404 compliance or general prevention of financial reporting misstatements, GAIT can help you determine which control objectives and controls are key through the use of a risk assessment. GAIT can be downloaded by IIA members free of charge, or for a reasonable price for nonmembers, from the IIA web site.

ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security

Standard of Good Practice for Information Security was first published in 1996 by the Information Security Forum (ISF). The ISF is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the development of information security good practices. Like ISACA, ISF is a paid membership organization with chapters throughout the world. The standard was last updated in October 2018.

ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security Highlights

Standard of Good Practice for Information Security contains guidance on security principles, control objectives, and controls in the following areas:

• Enterprise security management

• Critical business applications

• Computer installations

• Networks

• Systems development

• End-user environment

Although the document is divided into these main areas, there are reference tables so that specific control areas that may be present in more than one area can be found easily.

Standard of Good Practice Value for the CISA

Standard of Good Practice for Information Security can provide you with information security control objective statements and describes the controls that should be in place. If you are looking for specific controls, such as access controls or controls around firewalls or e-mails, a reference guide can help point you to the proper section within each area.

ISO/IEC 27001 and 27002

Organizations facing privacy and information security concerns may decide that they need to implement a formal ISMS to ensure that information security is managed, risks are assessed, and appropriate controls are put in place to mitigate risk to information security. Published in 2005 and updated in 2013 by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), ISO/IEC 27001 is a standard that organizations can use for developing, implementing, controlling, and improving an ISMS. ISO/IEC 27001 provides the general framework for the ISMS, while ISO/IEC 27002 provides a more detailed list of control objectives and recommended controls. The controls presented within the document act as a guide for those who are responsible for initiating, implementing, or maintaining an ISMS.

Organizations may choose to be certified as compliant with ISO/IEC 27001 by an accredited certification body. Similar to other ISO management system certifications, there is a three-stage audit process.

In addition to the ISF Standard of Good Practice for Information Security guide, there is complete coverage on the topics found in ISO/IEC 27002, COBIT, CIS 20 Critical Security Controls, plus a glossary, ISMS auditing guidelines for the management system and controls, implementation guide, and guides on IT network security and application security, to name a few.

ISO/IEC 27001 and 27002 Highlights

The concept of an ISMS centers on the preservation of

• Confidentiality Ensuring that information is accessible only to those authorized to have access

• Integrity Safeguarding the accuracy and completeness of information and processing methods

• Availability Ensuring that authorized users have access to information and associated assets when required

The ISO/IEC standard contains an introductory section and a description of the risk management process framework needed around information security controls. Each organization is expected to perform an information security risk assessment process to determine which regulatory requirements must be satisfied before selecting appropriate controls.

The 14 main domains in ISO/IEC 27001 and 27002 are

• Information security policy

• Organization of information security

• Human resource security

• Asset management

• Access control

• Cryptography

• Physical and environmental security

• Operations security

• Communications security

• System acquisition, development, and maintenance

• Supplier relationships

• Information security incident management

• Information security aspects of business continuity management

• Compliance

Control objectives and controls for each section are listed in the standards and code of practice. ISO/IEC 27001 focuses on the implementation of controls throughout the Deming Cycle, while ISO/IEC 27002 lists the good practice controls an organization can implement.

ISO/IEC 27001 and 27002 Value for the CISA

Those involved with implementing or assessing information security controls or the management of information security risk may find it helpful to look more closely into these standards. ISO/IEC standards documents can be purchased from the International Standards Organization.

NIST SP 800-53 and NIST SP 800-53A

NIST Special Publication 800-53 (NIST SP 800-53), “Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations,” provides a comprehensive catalog of security and privacy controls for U.S. federal organizations and information systems to support compliance with the mandatory federal standard FIPS Publication 200 Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems. Revision 4 of SP 800-53 was published in January 2015, revision 5 is in draft as of this writing.

Of special interest to the IS auditor is the document NIST SP 800-53A, “Assessing Security and Privacy Controls in Federal Information Systems and Organizations.” A companion to NIST SP 800-53, this publication guides the IS audit for auditing all the controls in NIST SP 800-53. For each control in NIST SP 800-53, this document describes what the IS auditor should examine, who she should interview, and what to test. Control owners will also derive value as they will know what would be expected of them in an audit; this will lead to better control design and operation.

NIST SP 800-53 Highlights

NIST SP 800-53 revision 4 contains almost 1,000 controls across 18 control families. FIPS Publication 199 requires organizations to categorize information systems as low-impact, moderate-impact, or high-impact, in terms of criticality, based upon the types of information they process. To support this framework, the NIST SP 800-53 has grouped minimum security control requirements security control baselines for low-impact, moderate-impact, and high-impact rated systems to provide a starting point for establishing expected control requirements.

The 18 control families in NIST SP 800-53R4 are

• AC – Access Control

• AU – Audit and Accountability

• AT – Awareness and Training

• CM – Configuration Management

• CP – Contingency Planning

• IA – Identification and Authentication

• IR – Incident Response

• MA – Maintenance

• MP – Media Protection

• PS – Personnel Security

• PE – Physical and Environmental Protection

• PL – Planning

• PM – Program Management

• RA – Risk Assessment

• CA – Security Assessment and Authorization

• SC – System and Communications Protection

• SI – System and Information Integrity

• SA – System and Services Acquisition

Appendix J in the publication contains a catalog of privacy controls. These sections are

• AP – Authority and Purpose

• AR – Accountability, Audit, and Risk Management

• DI – Data Quality and Integrity

• DM – Data Minimization and Retention

Privacy controls in revision 5 of NIST SP 800-53 will be integrated, not separated as they are in revision 4.

NIST SP 800-53 Value for the CISA

Those involved with establishing or auditing U.S. federal information systems and cybersecurity programs should be familiar with the NIST SP 800-53 control set. Moreover, IS auditors should also be familiar with NIST SP 800-53A, as this contains detailed guidance on auditing all the controls in NIST SP 800-53.

NIST Cybersecurity Framework

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF) was published in 2014 as a response to the Presidential Executive Order 13636, Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity. The order directed NIST to work with stakeholders to develop a voluntary framework—based on existing standards, guidelines, and practices—for reducing cyber-risks to critical infrastructure. The CSF is not intended to be another set of standards. Instead, the CSF is a body of work that is built around industry best practices and utilizes direct references to internationally accepted cybersecurity and risk management standards.

The NIST CSF is made up of three main components: the core, implementation tiers, and profiles. The core is broken down into five functions that each includes categories of cybersecurity outcomes and informative references that provide guidance to standards and practices that illustrate methods to achieve the stated outcomes within each category. The implementation tiers provide context on how well an organization understands its cybersecurity risk and the processes in place to manage that risk. Finally, the profiles assist an organization in defining the outcomes it desires to achieve from the framework categories.

NIST CSF Highlights

The NIST CSF core is broken down into the following five functions:

• Identify Develop an understanding of the business context and resources that support critical operations to enable the organization to identify and prioritize cybersecurity risks that can impact operations.

• Protect Implement appropriate safeguards to minimize the operational impact of a potential cybersecurity event.

• Detect Implement capabilities to detect suspicious and malicious activities.

• Respond Implement capabilities to respond to cybersecurity events properly.

• Recover Maintain plans and activities to enable timely restoration of capabilities or services that might be impaired after a cybersecurity event.

Four tiers are intended to describe an organization’s cybersecurity program capabilities in support of organizational goals and objectives. It is important to highlight that the tiers do not represent maturity levels or how well capabilities are executed. The tiers are meant to describe and support decision-making about how to manage cybersecurity risk and prioritization of resources. Here is a summary of the tiers:

• Partial Cybersecurity program may not be formalized and risks are managed in an ad hoc or reactive manner. There is limited awareness of cybersecurity risk across the organization.

• Risk Informed Cybersecurity program activities are approved by management and linked to organizational risk concerns and business objectives. However, cybersecurity considerations in business programs may not be consistent at all levels in the organization.

• Repeatable Cybersecurity program activities are formally approved and supported by policy. Cybersecurity program capabilities are regularly reviewed and updated based on risk management processes and changes in business objectives.

• Adaptive There is a consistent organization-wide approach to managing cybersecurity risk through formal policies, standards, and procedures. Cybersecurity program capabilities are routinely updated based on previous and current cybersecurity events, lessons learned, and predictive indicators. The organization strives to adapt proactively to changing threat landscapes.

NIST CSF Value for the CISA

The CSF can enable the IS auditor to develop and utilize common terminology that is easier for nonsecurity professionals to comprehend. In addition, the informative reference feature makes the NIST CSF a powerful and flexible model to facilitate development and auditing of a cybersecurity program against defined objectives and outcomes.

Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard

If an organization stores, processes, or transmits credit card data, it is subject to the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS). In 2001, Visa launched its Cardholder Information Security Program (CISP), which established a set of security requirements for merchants and merchant service providers. Shortly after, other card brands launched their payment card security programs, such as MasterCard Site Data Protection (SDP) Program, American Express Data Security Operating Procedures (DSOP), and the Discover Information Security & Compliance (DISC) program. This resulted in merchants and service providers that accepted multiple payment card types having to maintain compliance with multiple security programs. The PCI-DSS grew out the need to standardize security requirements across the major card brand security programs. In 2004, the payment card companies came together to establish this comprehensive set of security requirements for merchants and service providers.

The PCI Security Standards Council (PCI SSC) is the independent group that was set up to oversee the standard going forward. An important distinction is that while the PCI SSC manages the technical and operational aspects of the standard, the compliance enforcement actions are the responsibility of the individual card brands. A top-down approach is taken from the card brands where they hold the card-issuing banks (banks that issue consumers a credit card) and acquiring banks (banks that set up merchant accounts and enable merchants to accept credit card payments). The merchant agreement with acquiring banks will include a requirement for the merchant to maintain compliance with the PCI-DSS and requires all service providers that the merchant engages with to uphold those compliance requirements.

PCI-DSS Highlights

PCI-DSS v3.2.1 was released in May 2018. The standard comprises 251 control activities organized within six principles and 12 security requirements.

Merchant Levels Merchants and service providers are classified based on the number of credit card transactions they process. The classification levels dictate how the organization must certify compliance with the PCI-DSS.

Although each card brand maintains its own table of merchant levels, a basic summary of merchant levels is as follows:

• Level 1 More than 6 million transactions annually

• Level 2 Between 1 and 6 million transactions annually

• Level 3 Between 20,000 and 1 million transactions annually

• Level 4 Less than 20,000 transactions annually

It is important to note that Visa, MasterCard, and Discover use similar criteria, while American Express and JCB have their own classification criteria. Although American Express and JCB have their own criteria, it is generally accepted that if you are at a level for one provider, you will be considered the same for all.

Level 1 merchants are required to have quarterly external vulnerability scans performed by a PCI approved scanning vendor (ASV) and have an independent validation of compliance conducted by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) who tests the implementation of the PCI-DSS control activities and delivers a Report of Compliance (ROC). Level 2–4 merchants, depending on the acquirer’s requirements, may simply be required to fill out a much shorter self-evaluation, called a Self-Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ).

Service Provider Levels A service provider or merchant may use a third-party service provider to store, process, or transmit cardholder data on its behalf, or a service provider may manage components such as routers, firewalls, databases, physical security, and/or servers.

Service providers are classified in a similar manner as merchants. Although each card brand maintains its own table of service provider levels, a basic summary of merchant levels is as follows:

• Level 1 More than 300,000 transactions annually

• Level 2 Less than 300,000 transactions annually

Like level 1 merchants, Level 1 service providers are required to have quarterly internal and external vulnerability scans performed by a PCI ASV and have an independent validation of compliance conducted by a QSA who tests the implementation of the PCI-DSS control activities and delivers a ROC that the service provider will submit to the respective payment brands.

Similar to merchant levels, it is generally accepted that if you are at a level for one provider, you will be considered the same for all.

PCI-DSS Value for the CISA

The IS auditor may be called upon to assist in preparing an organization for a PCI-DSS compliance assessment. The PCI-DSS is a prescriptive standard by design and includes detailed testing procedures and guidance for each control activity. The PCI SSC publishes a number of supporting documents to enable consistent interpretation of the PCI-DSS.

CIS Controls

The Center for Internet Security (CIS) Critical Security Controls (CSC) was first published in 2009 through a partnership with the U.S. National Security Agency, CIS, and SANS Institute as a way to assist the Department of Defense in prioritizing its security initiatives. The working group that was formed utilized the premise that only actual attack information could be used to justify the control activities. Under this premise, the working group focused on gaining consensus to the control activities and the priority of control activities by sharing and analyzing cybersecurity attack experience and data. These exercises resulted in the 20 key control activities. The publication was originally owned by the SANS Institute; ownership of the standard was transferred to CIS in 2015. The framework is now known as the CIS Controls.

Historically, the CIS Controls utilized the order of the controls as the implied order of prioritizing an organization’s cybersecurity activities. This approach led to grouping the controls into categories of Basic, Foundational, and Organizational. However, it has been observed that many of the practices found within the CIS Basic grouping of controls can be difficult to implement for organizations with limited resources. This highlighted an opportunity to provide recommended prioritization of specific control activities believed to provide the best risk mitigation based on the real-world attack data reviewed while balancing resource constraints and effective risk mitigation. This resulted in the introduction of implementation groups within version 7.1 of the Controls. These groups are intended to assist organizations in focusing their security resources on specific objectives while leveraging the CIS controls.

The three implementation group categories are

• Implementation Group 1 An organization with limited resources and cybersecurity expertise available to implement subcontrols

• Implementation Group 2 An organization with moderate resources and cybersecurity expertise available to implement subcontrols

• Implementation Group 3 A mature organization with significant resources and cybersecurity expertise available to allocate to subcontrols

Version 7.1 was released in April 2019 and is the latest version as of this writing.

CIS CSC Highlights

The CIS Controls comprise 20 key activities, or critical security controls, that an organization can implement to mitigate cybersecurity attacks. The controls are described in a direct manner that is intended to be understandable by technical and nontechnical individuals:

1. Inventory and Control of Hardware Assets

2. Inventory and Control of Software Assets

3. Continuous Vulnerability Management

4. Controlled Use of Administrative Privileges

5. Secure Configuration for Hardware and Software on Mobile Devices, Laptops, Workstations and Servers

6. Maintenance, Monitoring and Analysis of Audit Logs

7. Email and Web Browser Protections

8. Malware Defenses

9. Limitation and Control of Network Ports, Protocols and Services

10. Data Recovery Capabilities

11. Secure Configuration for Network Devices, such as Firewalls, Routers and Switches

12. Boundary Defense

13. Data Protection

14. Controlled Access Based on the Need to Know

15. Wireless Access Control

16. Account Monitoring and Control

17. Implement a Security Awareness and Training Program

18. Application Software Security

19. Incident Response and Management

20. Penetration Tests and Red Team Exercises

CIS Controls Value for the CISA

The CIS Controls framework strives to provide a balance between providing descriptive, but not overly prescriptive, control activities that enable organizations to build cybersecurity program capabilities in a prioritized manner. The CIS Controls can enable the IS auditor to facilitate discussions utilizing common terminology for descriptions of control activities, which can simplify audit planning and execution.

IT Assurance Framework

In 2006 the ISACA board of directors approved the IT Assurance Framework (ITAF) project to address the need for audit and assurance standards. As the project matured, additional needs, such as taxonomy and guidelines, were identified and addressed. In 2014 ISACA published the third and current edition of ITAF: A Professional Practices Framework for IT Audit/Assurance.

The ITAF establishes mandatory standards that address IT audit and assurance professionals’ roles and responsibilities, knowledge, skills and diligence, conduct, and reporting requirements. The framework also provides nonmandatory guidance on design, conduct, and reporting on IT audit and assurance engagements and defines common IT assurance terms and concepts.

ITAF Highlights

There are three categories of audit and assurance standards in the document: general, performance, and reporting.

General Standards These are the guiding principles by which the profession operates. These standards deal with all IT audit and assurance activities conducted, and include

• Audit charter

• Organizational independence

• Professional independence

• Reasonable expectation

• Due professional care

• Proficiency

• Assertions

• Criteria

Performance Standards These focus on the IT audit or assurance professional’s conduct of assurance activities such as the design of audit and assurance activities, evidence, findings, and conclusions. ISACA IS Auditing Standards are the performance standards (current IS Auditing Standards are listed in more detail in Chapter 3). These standards include topics such as

• Engagement planning

• Risk assessment in planning

• Performance and supervision

• Materiality

• Evidence

• Using the work of other experts

• Irregularity and illegal acts

Reporting Standards These standards cover the report produced by the IT audit or assurance professional and address

• Reporting

• Follow-up activities

The ITAF documentation also outlines guidelines for applying the standards. Guidelines assist the IT audit or assurance professional with understanding enterprise-wide issues and IT management processes as well as processes, procedures, methodologies, and approaches for conducting an IT audit and assurance engagement.

ITAF incorporates ISACA’s IS auditing standards and the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics. In addition, all of the ISACA guidance is mapped to the framework. For more detailed information, see the ISACA web site.

ITAF Value for the CISA

The standards within ITAF are mandatory for all CISAs. It is recommended that all CISAs review the standards prior to certification and formulate good habits to ensure that standards are applied to any assurance work conducted. Although not mandatory, these guidelines, tools, and techniques can assist anyone needing to conduct IT audits or assurance activities, and they can even assist those on the receiving end of IT audit or assurance reports.

ITIL

In the 1980s, when the British government determined that the level of IT service quality provided to it was insufficient, it was clear that an IT process framework was needed. The Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA) sponsored the development of the Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL, pronounced EYE-till ), which began guiding organizations on the efficient and financially responsible use of IT resources within public and private entities worldwide.

The current version of ITIL, known as ITIL v4, released in January 2019, consists of a collection of books that contain guidelines for different aspects of good practice around IT service management (ITSM) and aligning IT services to business needs. When all volumes are combined, ITIL presents a comprehensive view of proper provisioning and management of IT services.

ITIL Highlights

ITIL is a high-level, user-focused process framework that defines a common language for ITSM processes. The framework describes the IT service organization that delivers agreed-upon services and maintains the infrastructure on which the services are delivered. One of the critical components of ITIL is that the services and maintenance must be aligned and realigned according to business needs. To do this, the framework closely aligns its five volumes with the Deming Cycle:

• ITIL Service Strategy This volume focuses on determining potential market opportunities with regard to delivering IT services, with sections dedicated to service portfolio management and financial management.

• ITIL Service Design This volume describes how to design proposed services with adequate processes and resources to support them. Availability management, capacity management, continuity management, and security management are key areas of service design.

• ITIL Service Transition This volume describes the implementation of the design and creation or modification of the IT services. Key areas identified are change management, release management, configuration management, and service knowledge management.

• ITIL Service Operation This volume provides guidance on the activities needed to operate IT services and maintain them according to service-level agreements. It focuses on the key areas of incident management, problem management, event management, and request fulfillment.

• ITIL Continual Service Improvement This volume focuses on how to ensure that the IT services delivered to the business are continually improved through service reporting, service measurement, and service-level management.

ITIL outlines the general IT processes needed to manage IT; the resources, outputs, and inputs utilized; and the controls that must be implemented to ensure business goals are met (such as policies and budgets).

ITIL Value for the CISA

Whether documenting, implementing, or assessing processes, the IS auditor can utilize the ITIL volumes for additional information on specific IT processes, such as change management or incident management. The framework outlines recommended controls to ensure that IT services are delivered as promised.

PMBOK Guide

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) is a guide on project management fundamentals and practices. The guide is published by the Project Management Institute (PMI). It began as a whitepaper in 1987 and was published as a guide in 1996. The sixth edition was released in 2017.

Not only is PMBOK a guide to project management, it also is an internationally recognized standard on project management practices. Those with an interest in obtaining certification in this area may want to look into becoming certified as a Project Management Professional (PMP) through the PMI.

PMBOK Highlights

The PMBOK Guide describes the many processes that are often used in managing projects. It consists of five process groups and ten knowledge areas.

Process Groups Forty-seven processes are used by project teams. These processes fall into five groups, which are consistent with the Plan-Do-Check-Act activities of the Deming Cycle:

• Initiating process group Defines the project/phase and gathers authorization

• Planning process group Defines objectives and courses of actions required to meet objectives and scope

• Executing process group Correspond to carrying out the project management plan

• Monitoring and controlling process group Regularly monitors progress and identifies variances from the plan; takes corrective actions

• Closing process group Concludes that all objectives are met and the service, product, or result is accepted by the customer/sponsor; end of the project

The Project Management Knowledge Areas Ten knowledge areas are needed for an effective project management program and the processes involved, as well as inputs, outputs, tools, and techniques for each. Each process belongs to a process group and is associated with a knowledge area. This section represents the bulk of the guide and details how the 47 processes interrelate. The ten knowledge areas are

• Project Integration Management

• Project Scope Management

• Project Time Management

• Project Cost Management

• Project Quality Management

• Project Human Resource Management

• Project Communications Management

• Project Risk Management

• Project Procurement Management

• Project Stakeholder Management

PMBOK Value for the CISA

As an IS auditor, you may be asked to take a closer look at the process for introducing new applications or systems into your organization. Many times, new applications and systems are delivered via a system/software/solution delivery life cycle and coupled with project management. Solutions are scoped and assessed, projects ensue, and a great deal of activity and documentation occurs throughout the process. Project management methodologies and frameworks can help you make sense of this madness.

In addition, project management skills can be valuable for an IS auditor. Being well versed in project management can help ensure that your IS audit work remains in scope and on budget and that you are planning your time adequately. For example, you will want to ensure that you are giving yourself enough time for audit planning, documentation, and accommodating complex interview schedules.

The PMBOK Guide can be purchased from booksellers worldwide or from the PMI.

PRINCE2

PRojects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE) is a structured project management standard covering project management fundamentals. The original standard was developed in 1989 by the U.K. Office of Government Commerce (OGC) specifically for IT project management. In 1996, PRINCE2 was released, representing a change in focus from beyond IT to general project management. In 2009, it was relaunched as PRINCE2:2009 Refresh (hereafter referred to as PRINCE2) and updated in 2017. In addition to becoming the de facto standard for project management in the U.K., the standard has been adopted by organizations worldwide, although not as commonly in North America as some of the other frameworks described in this appendix. As with ITIL, an individual may pass an exam to become accredited.

PRINCE2 Highlights

PRINCE2 consists of one main manual: Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2. It is similar to the PMBOK Guide in that it consists of processes and components, but it is different in that it fully describes the methodology and implementation techniques. The main concept behind PRINCE2 is that projects should have an organized and controlled start, middle, and end. Although it is not as comprehensive as PMBOK, PRINCE2 supplements general project management knowledge by specifically describing how to manage projects in a controlled and organized manner.

PRINCE2 is a process-driven framework and integrates well with other processes and practices, such as Agile Scrum. The framework details 45 processes categorized in seven process groups. The process groups lead you through the project life cycle, similar to the Deming Cycle:

1. Starting up a project

2. Directing a project

3. Initiating a project

4. Controlling a stage

5. Managing product delivery

6. Managing stage boundaries

7. Closing a project

Key inputs, outputs, goals, and activities are defined for each process. In addition, a maturity model is available to measure project management capability maturity. Another bonus is that the entire framework can be tailored for each project, as every process has guidance on how to scale it for small or large projects. This results in a flexible, scalable, and fully described framework.

Similar to PMBOK knowledge areas, PRINCE2 details seven “themes” that are deemed critical for project success:

• Business case

• Organization

• Quality

• Plans

• Risk

• Change

• Progress

PRINCE2 Value for the CISA

As an IS auditor, you may be asked to take a closer look at the process for introducing new applications or systems to your organization, including the software/system/solution delivery cycle and associated project management methodology and documentation. In addition, project management skills can be valuable for an IS auditor.

Similar to PMBOK, PRINCE2 will provide you with general guidance on project management processes and controls. PRINCE2 is complementary to PMBOK in that it helps shape and direct the use of PMBOK through the introduction of certain techniques. PMBOK will lay a more comprehensive foundation, whereas PRINCE2 will describe how to start managing projects and put the pieces together.

Risk IT

Published in 2009 by ISACA, Risk IT is the first comprehensive IT-specific risk framework that has been developed. The framework is based upon enterprise risk management frameworks such as COSO ERM and ISO/IEC 31000, making it much easier to integrate the management of IT risks into overall enterprise risk management. Risk IT also complements COBIT. Risk IT provides guidance for managing all aspects of IT-related risks, including project, value delivery, compliance, security, availability, service delivery, and recovery risks.

Risk IT Highlights

Two specifically significant documents have been published by ISACA: The Risk IT Framework, containing the principles, process details, management guidelines, and domain maturity models, and The Risk IT Practitioner Guide, which provides an overview of the Risk IT process model, describes how Risk IT links to COBIT and Val IT, and describes in detail how to use the model.

To ensure the effective enterprise governance and management of IT risk, The Risk IT Framework is based upon the following principles:

• Always align with business objectives.

• Align IT risk management with enterprise risk management.

• Balance the costs and benefits of IT risk management.

• Promote fair and open communication of IT risks.

• Establish the right tone from the top, while defining and enforcing accountability.

• Ensure a continuous process that is a part of daily activities.

There are three main domains in the framework: risk governance, risk evaluation, and risk response. Each of these domains is supported by three processes with various activities. Similar to COBIT, the guidance will provide a list of components, inputs and outputs, RACI charts, goals, and metrics for each process. The framework is depicted in Figure B-5.

Figure B-5 The Risk IT Framework

In addition to the guiding principles and process model mentioned earlier, the Risk IT Framework contains good practice guidance, domain maturity models, reference materials, and a high-level comparison of risk frameworks.

For more detailed guidance on governing and managing risk, The Risk IT Practitioner Guide walks you through the entire process, from defining a risk universe, developing risk appetite and risk tolerance, to setting up risk scenarios, responding to risks, and prioritizing risks.

Risk IT Practice Value for the CISA

If you are being asked to audit an IT risk program or identify, govern, or manage IT-related risks, The Risk IT Framework and The Risk IT Practitioner’s Guide will be of great value to you. These can also help with assessing risk and comparing it against the organization’s risk appetite and risk tolerance, or they can assist with the integration of IT risk management within an existing enterprise risk management program.

Val IT

Developed in 2006 by the ITGI, Val IT is a governance framework focused on the management of the IT-related business investments and portfolios. It is based on and attempts to address the “Four Areas” as described in John Thorp’s book The Information Paradox: Realizing the Business Benefits of Information Technology:

• Are we doing the right things?

• Are we doing them the right way?

• Are we getting them done well?

• Are we getting the benefits?

Val IT complements COBIT, and in fact the elements covered in VAL IT are included within the scope of COBIT, adding best practices for measuring, monitoring, and maximizing the realization of business value from IT investments. Val IT focuses on the IT investment decision processes and the realization of benefits, whereas COBIT focuses on the execution of IT processes.

Val IT Highlights

There are four Val IT publications: The Val IT Framework 2.0; Getting Started with Value Management; The Business Case Guide: Using Val IT 2.0; and Value Management Guidance for Assurance Professionals: Using Val IT 2.0.

The Val IT Framework 2.0 contains information on the framework’s seven key principles, three domains, key processes, and related practices.

Val IT is based upon the following seven principles:

• IT-enabled investments will be managed as a portfolio of investments.

• IT-enabled investments will include the full scope of activities required to achieve business value.

• IT-enabled investments will be managed through their full economic life cycle.

• Value delivery practices will recognize that there are different categories of investments that will be evaluated and managed differently.

• Value delivery practices will define and monitor key metrics and respond quickly to any changes or deviations.

• Value delivery practices will engage all stakeholders and assign appropriate accountability for the delivery of capabilities and the realization of business benefits.

• Value delivery practices will be continually monitored, evaluated, and improved.

The principles are applied to three Val IT domains: value governance, portfolio management, and investment management. Each of these domains contains various processes, each enabled by a number of key management practices. Similar to COBIT, for each process identified in Val IT, you can find associated inputs and outputs, RACI charts, goals, and metrics.

Getting Started with Value Management provides various approaches for implementing Val IT. Documentation includes assessment templates, maturity models, and approaches for managing and sustaining change.

The Business Case Guide: Using Val IT 2.0 provides guidance for developing an effective business case. Business cases are developed for IT-enabled investments and consider the following:

• Resources are needed for development

• A technology/IT service that will be supported

• An operational capability that will be enabled

• A business capability that will be created

• Stakeholder value that will be realized

This publication outlines an eight-step process for developing the business case that involves building a fact sheet, analyzing various data and risk, appraising the risk and/or return of the investment, documentation, and review.

Value Management Guidance for Assurance Professionals: Using Val IT 2.0 describes how to use Val IT to support an assurance review of IT investment governance for all three Val IT domains. Included is a set of assurance tests covering the full scope of Val IT as well as guidance for planning and scoping assurance activities.

Val IT Value for the CISA

Val IT publications, especially Value Management Guidance for Assurance Professionals: Using Val IT 2.0, can be useful tools should you need to audit or assess how IT investments and the IT portfolio are managed and governed. More information about Val IT can be obtained at the ISACA web site.

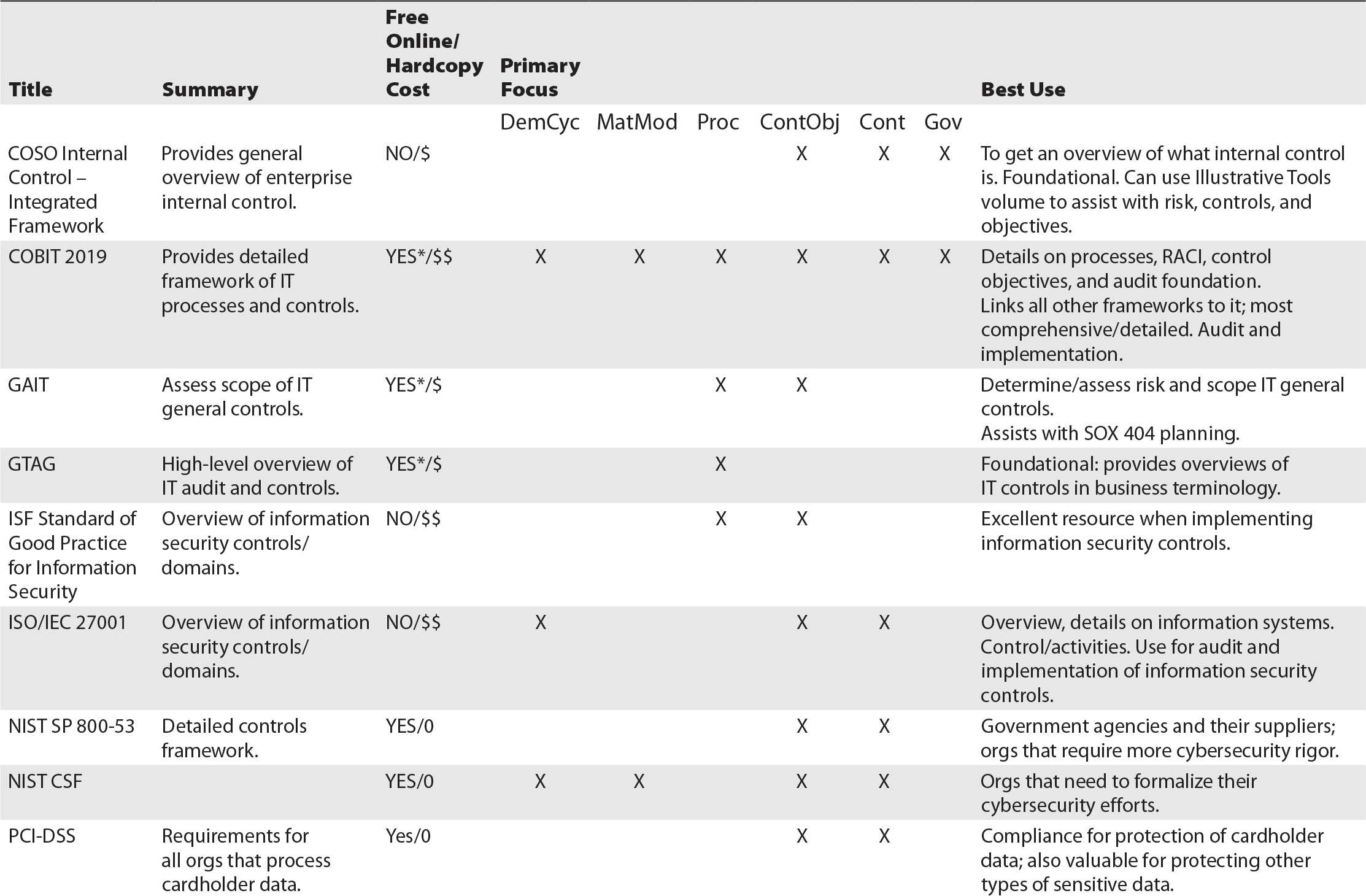

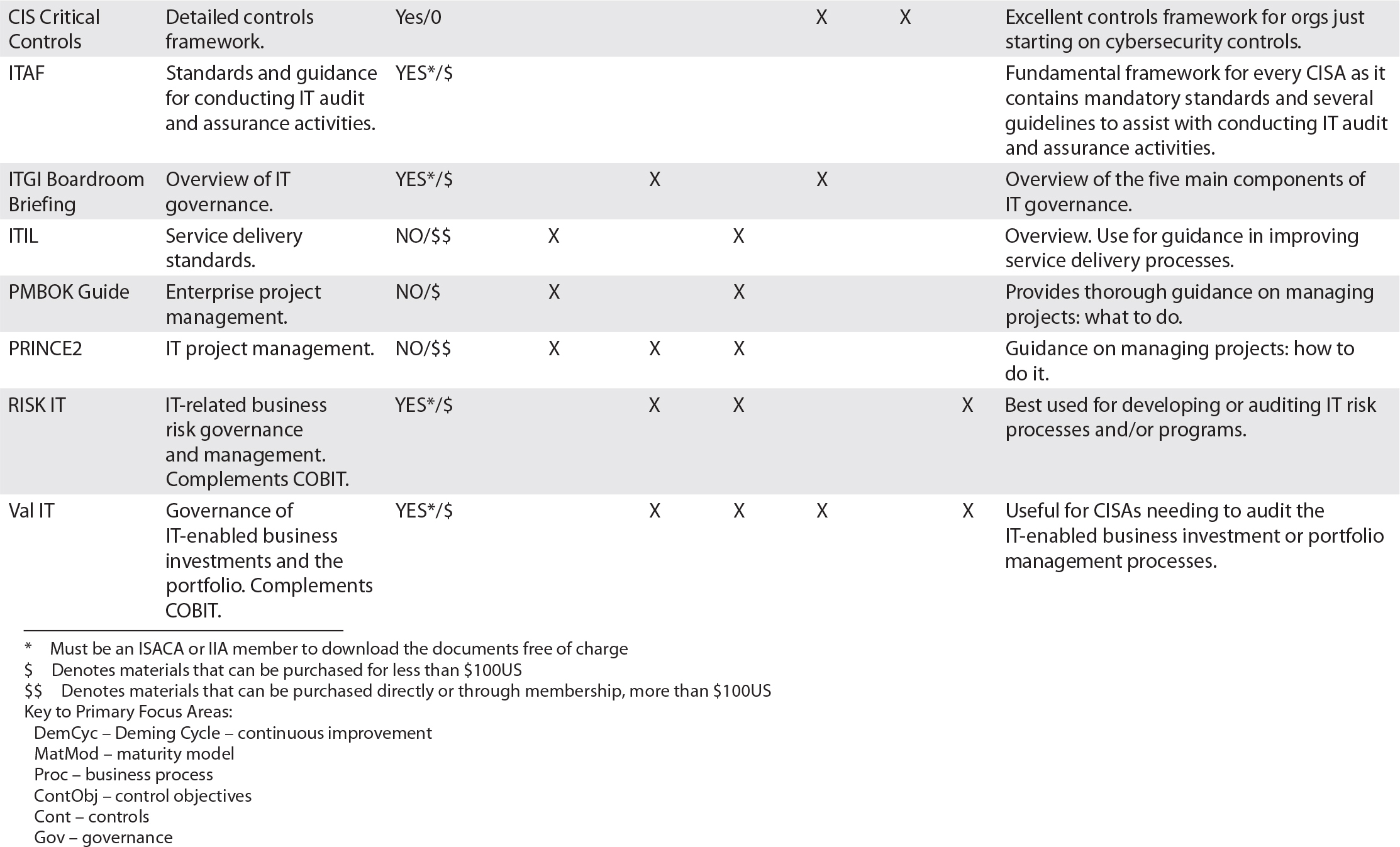

Summary of Frameworks

Table B-3 contains a summary of the frameworks discussed in this appendix. The table indicates whether the framework is available for a fee, the primary focus of the framework, and best uses for the framework.

Table B-3 Summary of Frameworks

Pointers for Successful Use of Frameworks

• Take time to learn the fundamentals of governance, controls, and processes. Become familiar with COSO, COBIT, and fundamental GTAG documents.

• Not one single framework is the “right” framework.

• There has been a great deal of research on governance, controls, and frameworks. Start here—don’t reinvent the wheel.

• Use frameworks for guidance and tailor them to your unique organization.

Notes

• Goals and objectives define what the organization is trying to achieve.

• Governance is what organizations put in place to identify and ensure achievement of goals, objectives, and strategies.

• A process is a set of activities that is put in place to maximize effectiveness and efficiency of operations. Organizations can manage operations through processes.

• Maturity models are often used to measure the maturity of process capabilities.

• The Deming Cycle focuses on continuous improvement through the implementation of a range of processes that address planning, execution, monitoring, and taking corrective actions.

• Control objectives are developed to ensure that business objectives are achieved.

• Control activities support control objectives and can be implemented within processes.

• Projects are temporary, unique, and have specific objectives and controls implemented.

This appendix focused on processes and internal controls, and described the various frameworks, methodologies, and guides available as resources. Now that we have examined the available resources, it’s time to put all of this to use. For an overview of conducting professional audits, see Appendix A.

References

• Board Briefing on IT Governance: 2nd Edition; IT Governance Institute. https://www.isaca.org/itgi

• Business Model for Information Security (BMIS); ISACA. https://www.isaca.org/BMIS

• Business Motivation Model; Business Rules Group. https://www.businessrulesgroup.org/bmm.shtml

• Certified in the Governance of Enterprise IT (CGEIT) certification; ISACA. https://www.isaca.org/cgeit

• CIS Controls. https://www.cisecurity.org/controls/

• COBIT; ISACA. https://www.isaca.org/COBIT

• COSO Internal Control – Integrated Framework; Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). https://www.coso.org/ic.htm

• Enterprise Risk Management – Integrated Framework (2004); COSO. https://www.coso.org/-ERM.htm

• Global Technology Audit Guides (GTAG); Institute of Internal Auditors. https://na.theiia.org