APPENDIX A

Conducting a Professional Audit

This appendix discusses the following topics:

• Auditing in the real world

• Carrying out the IS audit cycle

• Internal audits versus external audits

• Ethics and independence

• Writing audit reports

The goals and structure of this appendix are slightly different from the rest of this book. Whereas Chapters 1 through 6 convey information to the CISA candidate, here, the focus shifts to the professional world of the information systems (IS) auditor. It addresses the nature of different professional engagements common to information systems auditors. I review the stages of and responsibilities involved in performing a risk-based information systems audit for both internal and external auditors. This appendix also serves to introduce and frame examples of professional situations that may challenge an auditor.

This appendix reviews the process of performing an information systems audit, and in doing so, identifies how sections of the study materials in this book can be applied in the “real world.” By bringing the subject of conducting an IS audit “up a level,” I provide associations between concepts found in the main chapters in this book so you have real-life examples of a number of these concepts. This should help solidify material you learned from the rest of the book, and hopefully assist in recalling information while sitting for the test.

In addition, this appendix can be employed as a guide (or adapted to create a checklist) for the reader who is executing or participating in an information systems audit. The material here is based on methods used in professional environments that have succeeded in achieving high client satisfaction ratings and delivering quality audits.

To employ an automotive metaphor, the study material in the main chapters of this book may teach the reader about how a vehicle functions and relates to the road, while this appendix teaches the reader about driving.

Understanding the Audit Cycle

The information systems audit cycle is central to the profession of an IS auditor. The cycle itself could be executed by a single auditor, or the responsibilities could be distributed to individuals making up the audit team. In some professional situations, one or more sections discussed here may be unnecessary. The IS audit cycle described here is not the only cycle an IS auditor may perform, as the needs of different situations may require alternate procedures or approaches.

Candidates for the CISA exam will have had some experience with information systems auditing, but not all candidates will have had visibility into the whole end-to-end business process. Here, the stages of the cycle are illustrated as they would be considered by someone managing a professional audit.

For persons early in their professional career, this appendix unveils some of the stages that their supervisors may perform. Understanding these phases will help individuals early in their career see the big picture, deliver meaningful work, and hopefully hasten their advancement.

How the Information Systems Audit Cycle Is Discussed

Some components of an information systems audit cycle are uniform, regardless of the size of the client and the scope of the audit. Each stage discussed is a valid consideration during the course of performing a moderately complex audit project. This appendix provides a relevant audit skeleton, regardless of whether the auditor serves as an internal auditor within an organization or is brought in from outside the organization being audited. This is relevant for working on a variety of audit services, including SOC1/SOC2, SOX, OMB Circular A-123 auditing, financial audits, internal audits, report writing, compliance audits, and other services.

Although the focus is on executing an audit involving controls testing, many project stages will apply when performing other projects where an information systems auditor’s skills are required. It is not meant to be a complete reference when a project’s needs go beyond the scope of this appendix. Additional procedures will be required to deliver services supporting other functions, such as enterprise-wide risk assessments, project life cycle evaluations, and disaster recovery planning.

For the sake of “telling the story,” terms are introduced from outside of the CISA exam terminology.

“Client” and Other Terms in This Appendix

To ensure that the examples in this appendix are clear to the reader, this section explains how an experienced auditor’s vernacular employs the versatile term “client” contextually. In this appendix, the terms “client” and “client organization” refer to the business entity or departments within a project’s scope.

• Client The organization, department(s), and individual persons being audited.

• Client organization The broader legal entity being audited. In some cases, this can be defined as subdepartments within a larger organization.

To say “in front of the client” can refer to being outside the building, in a meeting, or sitting with a control owner.

More specific terms are employed for parties encountered within client organizations. This will assist in this discussion of the information systems auditing process. In this appendix, I use the following definitions to categorize client personnel as having the following roles:

•Audit sponsor The person or committee within the client organization that has determined that the audit needs be performed. When audits are required by regulation, the lead executive—commonly the CFO (chief financial officer), CIO (chief information officer), CAE (chief audit executive), CRO (chief risk officer), or CCO (chief compliance officer)—over the group being audited is most often the audit sponsor.

• Audit audience The party that will review and employ the information contained in a report. In the case of an internal audit, this is most likely the board of directors and/or audit committee of the organization, whereas for SOC1/SOC2 reporting purposes, this would more likely be the external auditors or customers of client organizations.

• Primary contact The person who serves as the initial point of communication between the audit team and client organization’s control managers and owners. The primary contact has the authority to schedule meetings and address issues, and may be provided regular status reports.

• Control owners The person(s) performing manual control activities or maintaining the successful performance of automated controls.

• Control managers The members of management who oversee control owners. They are ultimately responsible for ensuring the successful execution of control activities, and have a role in remediating issues discovered during testing.

“Client” as a Term for Internal Auditors

The term “client” usually implies parties are not under the same roof. In this appendix, “client” means the auditee—whether an audit is external or internal. A department within a larger organization may be the audit “client.” (As an example, in an audit focused on reviewing procurement practices, the procurement department is viewed as the “client.”)

With internal auditing, while the audit cycle will lack a bidding process, contract negotiation, and engagement letters, an auditor within an organization is still an independent party. Within this appendix, if there are points in the auditing process where there is a recognizable difference between performing work internally as opposed to externally, the difference is noted.

Overview of the IS Audit Cycle

This section describes the IS audit cycle and covers background information that may be pertinent to an auditor’s engagement. Included is a discussion on where audits originate and some of the particularities of different engagement types. Different reasons are addressed regarding why a client organization may initiate a project requiring the assistance of an IS auditor.

The IS audit cycle is a fairly standardized process, in that established steps are agreed upon as providing the basic structure for performing an information systems audit. Common milestones have been established. IS audit projects will involve some, if not all, of these milestones. This appendix explores the details of these milestones and activities, but at a high level, they can be viewed as:

• Project origination

• Engagement letter or audit charter

• Ethics and independence

• Launching a new project

• Developing the audit plan

• Test plan development

• Performing a pre-audit

• Organize a testing plan

• Resource planning

• Performing control testing

• Developing audit opinions

• Developing audit recommendations

• Managing supporting documentation

• Delivering audit results

• Management response to audit findings

• Closing the audit

• Following up on the audit

Each of these stages is covered in more detail within this section.

Project Origination

This section addresses the origination of information systems audit projects. This is the beginning of the information systems audit cycle. The following service areas are included in this discussion, although some of these service areas are not fully covered in this appendix:

• External attestations

• Internal audits

• Incident response and disaster response

• Life cycle reviews

• Governance reviews

• Staffing arrangements

This appendix surveys how the need for audit work in each service area is identified and originates as a project. This continues with a discussion of how an auditor’s help is solicited and their common roles in supporting certain projects.

External Attestations

An attestation is a statement made by an auditor that certifies or affirms the results of the audit. Often, an attestation takes the form of a letter or report that is signed by an owner or partner in an auditing firm (or by the leader of the audit department in the case of an internal audit).

Many organizations are required to have an audit based on government regulation or contractual obligations. External auditors provide results free from the pressures of a management reporting relationship. Strict ethical, and sometimes legal, guidelines prohibit relationships that can impair independence, whether in fact or in appearance. These independence measures seek to remove obstacles to an auditor’s objectivity when confirming the existence of practices and assessing the operation of controls within their organization—think of this as similar to the idea of testing for conflicts related to segregation of duties.

Examples of these services include

• Financial audits

• Bank system controls testing

• Lending or equity arrangements

• SOC1/SOC2 and other attest audits

• Certifications such as ISO and PCI-DSS

For external attestations services, a bid solicitation process is most commonly followed. The client organization issues a request for proposals (RFP) from external parties. The RFP will identify, at a high level, the scope of the work and some of the technologies involved. Proposals are collected and reviewed by the client organization, often including the audit sponsor and/or the primary contact. Proposals are vetted for approach, skills, terms, fees, expenses, and other considerations. The party selected by this process is then brought in to negotiate a contract (discussed further in the section, “Engagement Letters and Audit Charters”).

Management’s Need for an Independent Third Party

In addition to externally required attestations, the executive management of an organization can initiate projects for outside auditors. It is not uncommon for management to decide that a task should be handled by an independent third party. Management may have many reasons for hiring independent third parties to perform reviews, some of which include

• Unbiased

• Fresh perspective (“a new set of eyes”)

• Professional perspective, if a certified or accredited auditor is employed

• Not employing the necessary skills in-house

• Answering inquiries by external parties (i.e., performing agreed-upon procedures)

• Support management decision-making (such as “buy versus build” and system selection decisions)

• Gain access to advice from outside professionals with deep industry experience

Projects at the request of management are likely to report to a CFO, CIO, CAE, CRO, or CCO. Such projects may involve testing that supports goals that are not standard audit goals. It is important for auditors to be clear with a client regarding objectives and scope, and how to address requests for additional work.

Internal Audits

Internal audit (IA) departments usually report to the organization’s audit committee or board of directors (or a similar “governing entity”). The IA department usually has close ties with and a “dotted line” reporting relationship to finance leadership in order to manage day-to-day activities. This department will launch projects at the request and/or approval of the governing entity and, to a degree, members of executive management.

Regulation plays a large role in internal audit work. For example, public companies, banks, and government organizations are all subject to a great deal of regulation, much of which requires regular information systems controls testing. Management, as part of their risk management strategy, also requires this testing. External reporting of the results of internal auditing is sometimes necessary.

A common internal audit cycle consists of several categories of projects:

• Risk assessments and audit planning

• Cyclical controls testing (SOX and A-123, for example)

• Review of existing control structures

• Operational and IS audits

The central function of an internal audit department is the entity-wide risk assessment process. Annually, an attempt is made to identify and weigh all risks to an organization. This process results in ranking the organization’s “areas of greatest risk.” This is provided to the governing entity (commonly the audit committee) to review and determine the scope of the organization’s internal audit function. Areas of greater risk command more attention by the governing entity. They may choose to have the scope of the IA department’s work address these areas.

It is common for the IA department to maintain a multiyear plan (as discussed in Chapter 3), in which it maintains a schedule or rotation of audits. The audit plan is shared with the governing entity, along with the risk assessment document, and the governing entity is asked to review and approve the IA department’s plan. The governing entity may seek to include specific reviews in the IA department’s audit plan at this point. When an audit plan is approved, the IA department’s tasks for the year (and tentative tasks for future years) are now determined.

Even if the risk assessment is carried out by other personnel, IS auditors are often included in a formal risk assessment process. Specific skills are needed to communicate with an organization’s IT personnel regarding technology risks. IS auditors will use information from management to identify, evaluate, and rank an organization’s main technology risks. The outcome of this process may result in IT-related specific audits within the IA department’s audit plan. The governing entity may select areas that are financial or operational and that are heavily supported by information systems.

Internal audits may be launched using a project charter, which formalizes the project to audit sponsors, the auditors, and the managers of the department(s) subject to the audit.

Cyclical Controls Testing A great deal of effort has recently been expended getting organizations to execute a controls testing cycle. Most frequently, these practices are supporting the integrity of controls in financially relevant processes. Public corporations have needed to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 requirements, and U.S. government organizations have been subject to OMB Circular A-123, compliance with the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), and other similar requirements. Countries outside of the United States have instituted similar controls testing requirements for publicly traded companies and governmental organizations. Many industries, such as banking, insurance, and health care, are likewise required to perform control testing due to industry-specific regulations.

Financial leadership is required to affirm that controls testing cycles are operating successfully and that controls surrounding financial reporting are operating effectively. This includes control testing by qualified and independent auditors (common regulations require that a portion of the control testing require using an external IS auditor).

Organizations employ software tools to assist with tracking controls testing. These systems track the execution and success of control tests performed as part of a testing cycle, and can frequently manage archiving supporting evidence. Organizations may employ IS auditors to implement a system for tracking controls testing.

Many organizations have functioning internal audit departments. Most internal auditors come from a financial background and have limited knowledge of the practice of information systems auditing. Organizations that lack an existing internal audit department may outsource their whole internal audit function via the RFP process. IA departments may seek to augment their staff with IS auditors to cover internal shortcomings.

Establishing Controls Testing Cycles Young or growing organizations may not have established or documented internal controls testing cycles. IS auditors, working in conjunction with individuals focused on manual controls, will participate in the establishment of controls testing. The auditor produces documentation of controls through a series of meetings with management. During the process, auditors will develop process and controls documentation and confirm their accuracy with control owners through the performance of control walkthroughs.

These engagements are likely to occur when companies prepare to go public. Such companies need to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 requirements, which involve documenting controls and performing a test of existence, also known as a “test set of 1” or a “walkthrough,” for each identified key control.

Private companies will maintain SOX-equivalent documentation to retain the option of seeking public financing, or when lenders or private investors require it. Many organizations will find external resources to assist in the documentation and testing of applicable internal controls.

When auditors are bidding on engagements for establishing controls testing cycles, there are uncertainties regarding the amount of time this process will take. Factors that may add unexpected amounts of time include

• Functions prove complex or disorganized.

• Documentation provided by management could be out of date.

• The need for auditors to produce control procedures where none exist.

• Control weaknesses and failures may be uncovered, requiring unplanned remediation.

• Fraud may be uncovered, resulting in project interruptions and turnover of control owners.

If management has documented procedures or experience with controls testing, this process will take less effort on the part of auditors.

Reviewing Existing Controls Control structures change as an organization and the regulatory landscape change. Outside the organization, a change in regulations may change the focus of certain processes and controls testing. Guidance covering SOX and A-123 auditing has changed over time. For example, changes over time by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and other organizations have allowed a greater degree of reliance upon monitoring controls. Within an organization, objectives may change, and with them the technologies and procedures. New systems or new lines of business may change which controls are most material. IS auditors are often asked to review and update the individual controls within a controls testing cycle. They will update wording and may advise management on how to bring the controls testing closer in line with external guidance.

Early SOX compliance efforts often led to long lists of control activities that would be considered excessive by today’s standards. Older control structures predate more recent directives, causing an excessive testing burden for the organization. Business, process, and technology changes may have left parts of a control structure obsolete or not yet included. Organizations often seek third-party assistance performing controls rationalization—updating and “streamlining” their list of key control activities to realign their controls with both current regulatory directives and recent risk assessments. IS auditors may be tasked with updating controls documentation as an additional service while performing control tests.

Operational Audits Operational audits are typically internal audits. These audits involve internal reporting to management and/or an organization’s governing committees, and can cover any area of the business. These reports are done at the request of a member of executive management or the governing entity, and may originate from the discovery of an issue in the business, the annual risk assessment, or the established audit planning cycle. These audits often will be performed over a limited period, have a clearly specified scope, and result in issuing an internal audit report.

Operational audits require an auditor with experience in the function being audited. Many organizations will want to grow out their internal audit function from within their ranks so their auditors have a functional knowledge of the departments they audit. If an organization lacks an internal audit function, they often will seek audit professionals with experience in their industry.

Audits focused on operational elements will employ whatever methods of testing or analysis support the audit’s objectives, and may not include controls testing. Some examples of the objectives for operational and IS audits could include the following:

• Evaluate procedures within a department.

• Process reengineering within a complex function.

• Test compliance with policies.

• Prepare for a system implementation.

• Uncover internal inefficiencies.

• Perform data analysis for management decision-making.

• Identify improvement opportunities to existing systems.

• Detect fraud and the risk of fraud.

When an operational area relies heavily on supporting systems, it is common for an IS auditor to own part or all of the cycle of performing operational audits. For certain operational audits, an IS auditor’s background with the operation is important. Familiarity with the business of the department and the procedures performed is often required. A project could require an IS auditor with a financial background or experience with certain financial business processes.

Auditing Incident Response and Disaster Response

Incidents can take many forms, and can include but are not limited to:

• Internal and external hacking

• Network traffic failures

• Post-implementation problems

• Misuse of information systems

• Failure of key equipment

• Natural disasters

Many occurrences might lead to the formation of a “response team,” sometimes referred to as a computer incident response team (CIRT). This team is assembled to involve the appropriate parties from within an organization to handle the issue. Internal auditors are often included in a CIRT.

An organization that has experienced an “incident” is unlikely to have a clear approach to how IS auditors can assist, but auditors often have a role to play in the aftermath of an incident. An unplanned damaging event often leads an organization to gather special teams. These teams will seek to assess, contain, and recover from the incident, as well as design and implement changes that will prevent future occurrences.

An IS auditor has skills that are useful in these situations, but it is important to recognize that some of the skills needed are beyond the scope of the CISA study materials. A CISA certification does not by itself provide the preparation needed for gathering forensic evidence or performing technological remediation. A person with a CISA certification may, with appropriate oversight, prove a useful assistant to a forensic auditor or other expert. An IS auditor does have the skills to assess where control structures broke down or were insufficient, and can assist in or advise while developing controls as part of remediation. Independence, however, must always be considered, even during an investigation, and IS auditors should not be responsible for the actual implementation of controls. Once remediation efforts have been completed and new controls have been implemented, the auditor can confirm controls are operating effectively.

Incidents can be embarrassing for an organization, and can affect their reputation and relationship with a customer base, potential investors, and other organizations. During the course of remediation from an incident, it is not uncommon for executive management to hire external IS auditors to provide independent verification of the progress of remediation plans. Executive management can see this service as providing assurance to their customers and/or partners that they should be protected from the incident recurring.

Some “incidents” may be understood by executive management, but the necessary skills to perform remediation are in short supply—for example, a system implementation with faults requires an assessment independent of management responsible for the project, or an acquiring company has problems related to data migrated onto their systems from companies they acquired. It is not uncommon for an IS auditor to be contacted for these jobs. Some of these tasks can be handled by information systems auditing techniques; however, the more the task involves a consulting solution, the more it is likely to stray from the standard information systems auditing process. When an IS auditor is brought into these situations, they should be very clear about the scope of the work to be performed and ensure they have the appropriate skills at their disposal.

Project Life Cycle Reviews

Project life cycles are a central function of an IT department, and project management practices can come under review as part of risk assessments and other projects. Areas frequently addressed in project life cycle reviews include

• Tasks supporting implementing or upgrading existing software

• System development life cycle (SDLC) methodology

• Asset management

• Change management

• Patch management of critical systems

• Configuration management

IT projects often involve a great investment on the part of an organization. The success of these projects can be critical to an organization’s future well-being and may have a bearing on members of management’s future with an organization. Management has a strong interest in ensuring that their investment in the project goes well.

An IS auditor can assess life cycle reviews to cover an IT department from a number of different angles. SDLC reviews can cover segregation of duties of project personnel, quality assurance measures, or a review of issues tracking tools and associated controls. Reviews may be designed to assess whether certain project management “best practices” are followed, such as maintaining project plans and meeting minutes, performing and documenting appropriate user-level testing, and capturing approvals on customization design documents. These audits may assess compliance with management’s policies in addition to looking at common industry practices.

Examples of possible life cycle projects include the following:

• An organization has just implemented new financial accounting software. Financial auditors determine the change to systems is material and seek to gain an understanding of controls in the process of implementation. An IS auditor is called in to review project documentation and speak with key project personnel. The auditor will review scope documents, approvals for customizations, segregation of duties/responsibilities, test plan records, issues tracking, and other key records from the process. The IS auditor reports to the financial audit team whether the process is well controlled, and the audit team incorporates this information into their test plan development.

• Internal audit may perform an IS review that addresses the controls in an organization’s SDLC to ensure that proper review, approvals, version retention, and segregation of duties are performed in accordance with controls documentation.

• An organization is experiencing delays on an implementation project. Management is not sure whether this is due to the performance of the project manager or because of an underestimation of the project requirements. An independent reviewer is asked to speak with persons involved in the project and review project documents to provide feedback.

• A government agency is preparing to comply with new legislation and is hoping to clarify the scope of compliance projects. The new legislation will result in increased traffic through their agency. Agency management seeks to learn whether procedures and technology are prepared for the increased traffic. They don’t have the bandwidth to task their own people with the review, so they hire outside reviewers to report on what changes are necessary and what changes may be desired.

• An organization’s network security has been successfully compromised by ethical hackers (“ethical hackers” is a term signifying a professional services firm hired to test an organization’s security controls). Management has committed to performing remediation activities to prevent future intrusions. IT management is strengthening existing controls and pursuing projects that aim to institute new control measures. IS auditors are brought in at the request of executive management to validate IT management’s claims regarding the successful implementation of controls measures.

Life cycle reviews may be covered in part by methods discussed in this appendix, but some reviews may require procedures not addressed here.

Implementation Problems Problems from system implementations and data conversions are common, and management may be strapped to remediate the issues. Client management may seek the help of IS auditors as additional “bandwidth.”

Here is an example: A company is acquiring smaller competitors and migrating their information systems into one consolidated system. Attempts to report using migrated data show problems in the underlying data. Auditors are tasked with learning about the process and controls related to correctly loading data sets onto the system. The auditor will then test report data and attempt to identify the specific problems.

These tasks can be handled by information systems auditing techniques. The more the task involves a consulting-style solution, the more the project is likely to stray from the standard information systems audit process. When an IS auditor is brought into these situations, the auditor should be very clear about the scope of the work to be performed and ensure they have the appropriate skills to deliver on the task at hand.

IT and IS Governance Reviews

Often, IT and IS governance reviews are required by external regulations. Governance reviews are usually focused on management’s risk management and performance measurement responsibilities. Financial auditing procedures require governance evaluations. An auditor’s risk analysis could identify information systems as an area material to an organization’s control structure, such as within an e-commerce company.

Management’s risk analysis could also identify areas of IT governance to review. Management could request that an internal audit department or external reviewers be requested to assess whether an IT department is aligned with a company’s strategies or is delivering appropriate value for an organization’s investment in IT.

A few examples of IT governance projects include the following:

• Management is facing some long-term budgeting decisions, possibly including eliminating positions. Rather than determining which positions to eliminate, management finds an independent party to provide an impartial perspective on the value each of the groups within the IT department provides. Management wants IS auditors to provide feedback on whether each group within IT is efficiently delivering value to the organization and is appropriately sized.

• A manufacturing company is preparing for growth. The IT department has not changed much since the company was small. Management wants an outside reviewer to recommend ways to “tune up” the IT department ahead of the expansion. Management hopes IS auditors will identify key IT risks facing expansion and work on developing an IT governance structure appropriate for a larger organization.

• Auditors are asked to review management’s security policies and offer recommendations for improvement.

Organizations may seek the help of IS auditors to provide recommendations to strengthen their governance function.

Staff Augmentation

When an organization has the ability to oversee the work of an IS auditor but needs additional resources to get work accomplished, they may opt for outsourced or co-sourced staffing arrangements. It is not uncommon to temporarily requisition the help of a skilled IS auditor to support controls testing or to serve on special teams (such as a CIRT). In this situation, the IS auditor reports directly to management in a client organization. In these situations, the auditor may perform a limited part of the information systems auditing cycle.

Engagement Letters and Audit Charters

Engagement letters govern the terms of the audit engagement when external auditors are used. This section lists a few of the general terms and goes into more detail on a few subjects of interest to auditors. General subject areas addressed within the engagement letter include

• Scope of work to be performed

• Distribution of the report

• Rates, time estimates, and fees

• Ownership of workpapers

• Terms for addendums

• Nondisclosure agreements

• Audit charters

Audit organizations and client organizations will both review a contract, and each party may require specific wording. Some contract negotiations can prove lengthy.

When audits are externally required, the party serving as audit sponsor may not be supportive of the audit. In these situations, the audit may not be welcomed by the primary contact or the control managers. Thus, it can be beneficial to give extra attention to:

• Audit terms on turn-around time for requests

• Availability of control owners and other key personnel

• The relationship with the primary contact

• Frequency and type of status reporting

Distribution of the Audit Report

The outcome of an audit is an audit report, a written explanation of the audit project, including the project’s objectives, the controls tested, and the auditor’s opinion of the effectiveness of each control. Most audit reports are solely for use by an organization’s management and governing entities. Reports will contain language reflecting the limited distribution and use of the report. The audit organization will only reply to inquiries regarding the report with members of management and no other parties. For example, the cover sheet and the footer on each page of the report can include the following phrase:

“This report is restricted to business use by management of XYZ Corporation and is not to be relied upon by any other party for any purpose.”

Certain reports, such as an SSAE 16 or SOC1 (formerly SAS 70) report, are for distribution to third parties. The engagement letter will state clearly the terms under which parties are permitted to receive these reports, and will provide a process for getting permission from the audit organization if they seek to provide the report to another party.

As an example of contract terms surrounding a report, SSAE 16 clients are forbidden from distributing a report to parties other than those using the control information in the SSAE 16 report for management’s review and to provide to their financial auditors. This means client organizations are not permitted to share this report with a potential client as a marketing tool without express written permission from the audit organization. If management does distribute a report beyond the terms of the engagement letter, the audit organization is no longer responsible for the content of that report if relied upon by a nonpermitted third party.

Rates, Time Estimates, and Fees

Part of an engagement letter will address the billing for services. Many attestation engagements are fixed-fee engagements, although additional billings may be agreed upon with time budget overruns or changes in scope. Many nonattestation (in other words, professional services instead of audit) engagements will bill based on hourly rates. Rates could be blended across teams, or could identify individual rates for specific resources. The contract could identify the degree of detail the client will receive on their statement.

Expenses are usually addressed in this section. Any conditions on expenses will be spelled out here. Clients may only permit certain kinds of expenses, or may ask for invoices with itemizations. Clients often select nearby audit firms that can provide resources without incurring travel or lodging expenses. Larger audits may draw resources from all over the country, and may incur sizeable expense bills.

Ownership of Workpapers

For external auditors, ownership of workpapers is different in attestation and internal audit engagements.

When a certified professional is signing off on an audit, they retain ownership of workpapers because they may be asked to defend their opinion with evidence. In some engagements, auditors may not have a problem providing a copy of part or all of the workpapers to management. Audit documentation of procedures is sometimes shared with management, and the documentation of test results beyond the report may be shared with management to support remediation efforts. In some external audits, ownership of audit workpapers is retained by the auditors, such as a bank requiring compliance testing from service providers.

Internal audit engagements are services done on behalf of management, and management retains ownership of audit documentation. IA departments commonly document their work in a combination of paper and electronic workpapers. Document retention requirements vary by industry and individual organization, and should be clearly understood by internal auditors to ensure internal and/or external retention compliance.

The ownership and sharing of workpapers will be addressed in the engagement letter.

Terms for Addendums

Most contracts prepare for the possibility that they can be extended with an addendum or change order. The addendum can increase or remove scope, extend deadlines, and add audit cycles based on the terms of the original engagement letter.

Nondisclosure Agreements

Because auditors gain access to proprietary information during the course of the audit, they are almost always bound by nondisclosure agreements (NDAs). These may be signed by the individual auditors, or for auditing firms, and they may be signed at an engagement level covering all team members. It is worth noting that NDAs usually do not cover disclosure to legal or regulatory authorities if fraud or other illegal activities are discovered during an audit. In some cases, an NDA is not signed but similar nondisclosure-type language is included in an engagement letter or contract.

Audit Charters

Audit charters are used for projects internal to an organization. Internal audit projects will often employ an audit charter. They prove useful to ensure management’s buy-in within an organization. Audit charters provide assistance to the project by communicating and formalizing the following:

• Sponsorship by executive management

• The goals of the project

• The planned time frame for audit activities

• Obligations of team members

• Expectations of team members

Chartered projects will often be kicked off with a meeting. This will help the team by allowing introductions to be made between team members in different departments. The event also serves to promote teamwork and reinforce the goals, obligations, and expectations of the project.

When an outsourced IS audit resource is brought in to a chartered audit project, it is important that the auditor become familiar with the audit charter. This will allow the auditor to understand what has been communicated to client management and control owners.

Ethics and Independence

It is important that the auditor maintain independence from the client organization in both fact and appearance. This appendix will provide a few examples, but to comprehensively address the subject, refer to the discussion on ethics, independence, and the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics in Chapter 3.

Independence in Fact

Avoiding issues of independence in “fact” is rather straightforward. An auditor may not audit their own work, and may not report on testing if the subject of testing is a function owned or managed within their reporting relationship. The auditor may not design or be part of implementing controls and be called on to test those controls. Some examples of this include the following:

• An auditor has had the responsibility of implementing the new AR (accounts receivable) module as part of the ERP (enterprise resource planning) implementation team; the auditor should not be performing control reviews on this system.

• An auditor has been tasked with the daily monitoring of the firewall log. They may not perform testing as to whether the firewall log is regularly monitored.

• An auditor has a reporting relationship with a control manager. The auditor may not test controls managed by that control manager.

In addition, one should avoid testing the work of control owners or control managers when the auditor has family, intimate personal relationships, or external business relationships involved.

Independence in Appearance

Avoiding issues of independence in “appearance” is where an auditor faces more challenges. Gifts from the client are one area where judgment can be required. Fortunately, an auditor often is able to lean upon workplace policies in such situations. Common workplace policies include forbidding gifts over certain values and getting permission to accept certain gifts (such as tickets to a baseball game). Regardless of policies, an auditor must exhibit care when accepting gifts. A few examples are discussed here.

• The client organization’s CFO offers the team coffee mugs with the company’s new logo. Since this item has a limited cost and has marginal value, and is also a promotional tool for the company, there should not be an issue of independence in appearance.

• A control manager at the company offering to pay for a coffee may be a limited and acceptable gift.

• The CFO met the audit team for dinner and covered the bill. This can be acceptable as team building. The CFO then seeks to fund a night on the town with drinks and entertainment; this may be perceived as crossing the line.

• Small talk with a control owner about their office decorations leads to them offering you a gift from their collection of sports memorabilia. This could be perceived by the client as impairing independence.

Launching a New Project: Planning an Audit

A new project is on the table. The client wants auditors to start work soon, and so the process begins. Often in external audits, clients will limit the information provided until engagement letters and nondisclosure agreements have been signed. Most external audit organizations severely limit the amount of work auditors are permitted to perform on a project before the client has signed the engagement letter. To ensure that valuable time is not wasted, management waits until both the audit firm and the client have a clear and formal understanding on the scope and purpose of the audit.

Understanding the Client’s Needs

When a client organization decides that an audit is needed, they will usually describe their needs in writing and use a formal or informal selection process to choose an auditor. This selection process is centered on communication between the audit organization and the client about the client’s needs. A client needing a signed attestation still looks for the best audit firm for their “needs.” A client has reasons in addition to price to consider when selecting an audit firm. If an audit firm does not have experience in the client’s industry or technologies, the auditors may not work effectively with management. If a client is the smallest in an auditor’s book of business, they might be concerned about the level of service they will receive. A firm may be selected because of experience with an area of a client’s needs that are peripheral to the audit scope, and management’s decision to perform such an audit could relate to these needs. Understanding the reasons behind an audit can be important to successful planning and meeting client expectations.

A client organization may open up with more detailed reasons once auditors are selected and nondisclosure agreements are signed. Having such conversations with the primary contact or the audit sponsor early in the audit can provide valuable information to the audit team.

Some examples of a client organization’s needs that may factor into an audit include

• Augment documentation of new or changed procedures

• Get an internal audit function operating

• Update an outdated controls infrastructure

• Assist in the education of a new executive

• Support a financing relationship

• Repair relationships damaged by a previous control failure

• Meet contract conditions by providing an audit report by a certain date

Knowing the reason behind management’s decision to perform an audit will allow audit personnel to:

• Better understand the client’s risk environment

• Provide more useful feedback on their controls structure

• More accurately plan for the audit

• Focus extra testing on the most critical control objectives

• Meet client expectations and deadlines

• Provide meaningful reporting based on the results of the audit

IT managers frequently ask their auditor about how they compare with their peers.

Preliminary Discussions Preliminary discussions between audit management and client management will set the stage for how well the parties will work together. It is important at this phase to anticipate challenges that may be faced during the audit. Common things to address in these initial discussions are

• Clarifying scope by confirming an understanding of client needs and their risk environment

• Acquiring more detailed information on employed technology and a deeper understanding of how it supports the organization’s objectives

• Establishing engagement procedures, such as scheduling control owner time and requesting documentation

• Setting expectations, such as frequency and depth of status reports and review of testing exceptions

Both the client and the audit manager have an important investment in the success of this phase. The client organization is hoping to maximize the benefit of the service, so they may identify areas where they would seek professional advice. The client representative may aim to minimize internal disruptions and ask the auditor to observe certain practices.

Understand the Technologies Employed The audit manager uses information on employed technologies when developing the audit plan and when assigning resources to test controls.

When involving a third-party audit resource, a client’s selection process will limit the amount of information they share publicly about their systems. If there is a bidding process, it may permit formal or informal Q&A, where answers will be provided in response to vendor inquiries for the purposes of estimating effort. When the audit is launched and NDAs are signed, the client should be willing to share relevant documentation and information freely.

An audit manager also will be gathering information on the nature of testing that will be performed. Some questions an audit manager may consider include

• What kind of security testing is required

• What kind of process evaluation is required

• What kind of application testing is required

• What relevant customizations exist

• Are any in-house-developed technologies employed

In these preliminary discussions, the audit manager needs to gather more specific information on the technologies involved and the testing to be performed. The version numbers, implementation dates, and an idea of the transaction volumes are useful information. The audit manager will use such information during audit planning.

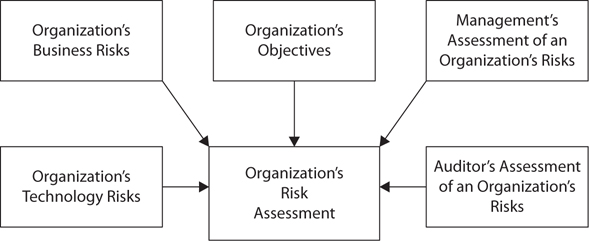

Performing a Risk Assessment

A risk assessment process takes into account the innate risks of a certain operation and considers information from within the organization. Auditors will weigh information from several sources when performing a risk assessment, as illustrated in Figure A-1.

Figure A-1 Different considerations in a risk assessment

It is common to have financial information available for the purpose of assessing the materiality of certain activities. Here are some examples:

• An organization may have extensive automated transactions in revenue and have very few assets tracked within their asset management system. Therefore, there is less innate risk surrounding asset tracking, but thorough attention needs to be given to the systems supporting the revenue cycle. There could be a high risk of data redundancy or incomplete capture of information in the event of system failure.

• A debt collection service outsources the software maintenance for their core collections-processing software to a software vendor. Therefore, risks relating to change management controls surrounding their core systems are reduced. However, because it is a high-transaction environment, data backup and restoration controls are elevated in criticality.

A risk assessment is arguably the most important aspect of an audit. Without a risk assessment, high-risk situations may not be addressed sufficiently during an audit. Management may not realize the opportunity to reduce serious risks.

Audit Methodology

Audit methodologies are designed by audit management and standardize how parts of audits are performed. Methodologies are the procedures used by the audit team to perform an audit. They can be as simple as requiring scope to be documented and approved, to employing audit software and detailed procedures that govern the entire audit process.

ISACA considers the following items so central to the audit process that all audits will at least generate documented statements addressing:

• Audit charter

• Audit scope

• Audit objectives

• Audit testing program

Audit organizations that regularly provide certain services will standardize methodologies for performing their audits. These methodologies can assist an organization in ensuring completeness, maintaining standards, and streamlining the process of management’s review of audit work that is done.

Methodologies can include policies, procedures, software tools, templates, checklists, and other means of providing uniformity across the audit process. These methodologies are documented and taught to new members of the organization.

Documented methodologies can serve to govern many stages of the process, such as:

• Bidding on RFPs

• Risk assessments

• Scope

• Objectives

• Resource allocations

• Comprehensiveness of testing

• Sample size guidelines for testing

• Report templates

• Completion checklists

Methodologies will provide a structure for achieving milestones within the audit process. For example:

• Risk assessment An audit firm’s risk assessment approach involves employing a spreadsheet predesigned to compute an aggregate score from several different risk measurements. Form letters may be used to communicate with management and collect their feedback on the client organization’s risks. Management’s feedback can be populated into the spreadsheet along with auditors’ assessments, and the risks are ranked.

• Budget A budget tracks time and rates incurred by auditors. This will be developed initially in the RFP process and updated in the planning process. Actual time incurred will be compared with the budget so audit management can better understand how to plan for future engagements.

• Lead sheets Lead sheets are intake forms used by auditors to capture and organize test information. They provide a uniform method to represent test results and enable audit management to perform a formulaic review of test results.

• Testing standards In order to maintain a rigorous standard of testing to support their reputation, an audit organization institutes testing standards. These standards require different methods of testing in order to pass a control test. Testing methods are identified as follows: collaborative inquiry, observation, inspection, and reperformance. In addition, each control objective must be supported by one form of substantive testing.

• Auditing software Large audit organizations frequently enforce their audit methodology with software that attempts to accommodate as much of the audit process as possible. These programs may accommodate most audit possibilities and enforce that certain procedures be executed by the audit team. They may even manage images of workpapers so that the software captures all audit documentation.

Methodologies used by audit firms may be designed to meet requirements published by regulatory organizations, such as the AICPA or the U.S. government’s Office of Management and Budget.

Developing the Audit Plan

An audit plan is a project plan designed for performing an IS audit. The audit plan, like a project plan, is a tool for tracking tasks and forecasting the time and resource needs of the audit process. It will describe the audit methodology to be used and lay out milestones and the sequential dependencies for the different tasks within the audit. The plan is updated with progress milestones, and may be adjusted with certain audit changes.

In addition to serving as a high-level audit plan, in the beginning, the audit plan serves to organize the stages of risk assessment, audit objectives, and the initial assessment of client procedures.

The audit plan does not track the detail of audit testing—this is tracked in the audit testing matrix and the lead sheets.

Gathering Information: “PBC” Lists

A “Provided by Client” (PBC) list is a common tool used by auditors for managing information requested from the client. It provides a consolidated list that the auditor can use as a record of request for process documents and records, and provides an effective checklist for tracking receipt of information. It will also help a primary contact manage fulfillment of auditor information requests. Several PBC lists may be needed during an audit. PBC lists should be dated when they are delivered, and, if possible, they should document an agreed-upon delivery date.

Initial Information Requests At the beginning of an audit, the auditor will require information about the organization. Common requests include

• Organizational charts

• Company directory

• Controls documentation

• Relevant reports or other information

This information will be used to prepare for and execute the audit. The list may also identify documents that a client has indicated exist, such as an information security policy document.

A Client’s Preparedness for an Audit

When an organization is facing their first audit, auditors frequently include in their plans an evaluation of the client’s preparedness. A client may have a need for an audit, but may not be prepared. In attestation situations, the client organization may not yet be ready for an audit. A few possible examples of this include the following:

• A company hopes to undergo an initial SSAE 16 audit, but the control infrastructure is not yet documented or in place.

• A company has experienced significant growth. New ways have been devised to perform key processes. Procedures are inconsistent, and documentation is incomplete.

• Changes to business products, processes, and supporting technologies have left controls documentation out of date.

• New control procedures have been only partly implemented.

• Logging in key systems hasn’t been configured correctly, so there is inadequate capture or retention of audit information.

• There has been turnover of key control owners or control managers.

If a client organization’s support for an audit is below par, the first order of business is housekeeping. If the engagement letter does not account for providing services to help the client prepare, it may be necessary to delay the launch of an audit. Some challenges may be addressed by expanding the scope of the engagement letter to include the auditors providing assistance (such as with updating procedures) ahead of an audit. This is, however, a tricky issue: in an attestation or external audit, this is most frequently not possible or desirable due to independence or regulatory issues—auditors can’t audit the structures they help to develop.

Developing Audit Objectives

An audit’s objectives clarify the goals of the audit. Audit objectives also ensure the audit complies with applicable standards, laws, or regulations. Objectives are clarified in a formal document and retained in project workpapers. The objectives provide a basis for measuring the success of testing, and are central to an audit report’s opinion.

Objectives are developed by giving consideration to several different sources:

• The engagement letter or audit charter addresses the nature of the subject of testing and the expectations of reporting, and provides a central pillar to an audit’s objectives. This may focus on external security, operating effectiveness, or the correctness of transactions and processing.

• At this point, auditors will understand the nature of the client organization’s business and have discussed the key processes at a high level.

• An overall understanding of the organization’s risks from the risk assessment process will be incorporated.

• An understanding of a client’s needs for launching the audit will also be considered. This may reveal the goals of management in conducting the audit or clarify the nature of a third party’s interests in the outcome of the report.

Statements of audit objectives may incorporate additional perspectives. Figure A-2 illustrates how an audit objective is developed through the consideration of many information sources.

Figure A-2 Audit objectives are developed using information from several sources.

For example, an audit engagement letter identifies a client as needing controls documentation and limited financial controls testing. Auditors are aware of new financial systems. The risk assessment shows that financial auditors annually perform test procedures on manual and automated controls within the financial software of an organization. Conversations with management reveal that they hope to update documentation, confirm the success of their system implementation, and provide financial auditors with a report that shows system controls are operating effectively so that they can reduce the scope and cost of the financial audit. The objectives of the audit will be focused on updating procedure and controls documentation for the new system and testing new software controls.

Developing the Scope of an Audit

An audit’s scope is documented in a series of statements addressing the processes and/or systems to be reviewed and to what depth. It will address how to enact the audit’s objectives. The stages leading to the development of an audit’s scope are illustrated in Figure A-3.

Figure A-3 Audit objective and risk assessment help to determine audit scope.

A risk assessment has identified the areas with the greatest risk, so an audit scope will be constructed to address areas of greater risk. For example, testing of low-risk areas may focus on a small number of key controls when more robust testing is called for in areas with greater risk.

Similar to casting a net, the scope statement will identify what is included under the net and set the boundaries of what is outside it. A well-defined scope will assist in the development of focused test plans.

Examples of project scope statements include

• Testing addresses internal and external access to key systems, including procedures to set up accounts within Active Directory, password controls, VPN administration, and reviewing the network configuration and the firewall rule base. Not included in the scope are inquiries into firewall rule-base areas beyond those controlling external access, application access beyond network connectivity, or network penetration tests.

• Controls surrounding files feeding financial information into the financial system are the focus of testing. This includes testing controls and validating report values from systems in the revenue cycle, billing, and AP, which are managed outside of the financial system. Excluded will be any testing of data once it is within the financial system.

If, for some reason, testing issues reveal a need to go beyond the scope of an audit, auditors and the client will need to discuss the expansion of scope. This can happen when controls fail and compensating controls need to be tested. When auditors are externally sourced, any augmentation of scope will need to be formalized through a signed addendum to the engagement letter.

Prior Period Issues When an audit fails a test, succeeding audits will retest the failed test. When developing scope, audit reports from a prior period must be reviewed so auditors understand which issues require revisiting. An exception from a prior period may have been fixed, in which case audit documentation and testing plans may need to adjust to changes. Projects remediating issues to primary controls may be in-process, so only secondary controls are available for testing.

Expanding Scope In certain audits, such as internal audit reports, management may have some leeway in changing the scope during the reporting period. Understanding procedures or testing exceptions may reveal an area where management needs to dig deeper. It may be more economical to augment the current audit than to perform a procedure as part of a subsequent, currently unscheduled audit. Auditors are most likely available and are currently immersed in the procedures. Management may wish to push deeper to get to the root of an issue immediately.

Developing a Test Plan

When an audit’s scope has been approved, it’s time to develop a test plan. This section covers stages that go into developing the test plan. Audits that are performed on a previously established cycle may base much of their test plan work on plans used in prior audits. However, auditors must avoid any temptation to simply reuse an audit plan. It is very important that an auditor revisit audit objectives and reevaluate the scope of an audit for each audit cycle. Failure to do so can lead to serious audit problems when testing performed fails to satisfy audit objectives. This is especially important in situations where new systems have been implemented, changes have occurred in the business, or control issues have been identified in the past.

Understanding the Controls Environment

When an auditor is preparing the test plan, information is drawn from several sources. If the audit is not in its initial year, documentation will be available from previous audits. Auditors who have performed the same audit in prior periods will have historical knowledge. Client management is consulted to update procedure and controls documentation as well as to identify the control owners.

When auditors collect information on the controls environment, they often use PBC lists. Upon review, auditors may find provided information falls short of an auditor’s needs, requiring additional information requests. Shortfalls might be due to procedures that are new to the control structure or that have not been previously tested. It is common for auditors to meet with client management during this process.

Understanding the Client’s Procedures An auditor must understand a procedure before she can effectively plan and perform testing. Auditors begin by reviewing information provided by the client. Procedure documentation may be provided in a number of different forms:

• Financial audit write-ups CFOs usually keep copies of the process documentation generated by financial auditors. It is common for a CFO to make these available to audit teams when areas are in scope. These could also include written procedures and systems-level documentation.

• Internal audit documentation If the internal audit department tests controls on a cycle, the department keeps procedure documentation regarding the controls they test. Other auditors can benefit greatly from this documentation when it is within an audit’s scope.

• Management procedure documentation Management may have procedure documentation, such as instructional or reference material for employees (e.g., desktop procedures). A department’s policies may contain procedure documentation. Management may also retain procedure documentation from previous auditors.

• Instruction manuals When management trains many people to perform the same procedures, a training department may provide instruction to employees. Training material may provide instruction on control procedures that are within the scope of the audit.

• Checklists Management may oversee a process with a checklist. If a checklist is provided, it will offer a high-level understanding to auditors (as well as provide evidence of a controlled environment), but follow-up is likely to be required.

• Walkthroughs Auditors may determine that they need to perform a walkthrough of a process or transaction in order to document their own understanding of procedures used. The result of these walkthroughs can be a narrative of the process, flowcharts, or a control matrix that documents the control points in place.

Other sources may provide information on procedures as well.

An auditor must understand a procedure in the context of the audit. The impact of a procedure in relation to the audit objectives is important when understanding controls within the procedure. This will affect the degree or depth of testing that should be employed.

Many auditors bring to the table experience with procedures performed (or technologies employed) at other organizations. An auditor who has experience elsewhere can often more quickly understand a similar procedure (or technology) in a new environment. Such experience can also assist by being available to a junior auditor who is responsible for a subject for the first time.

Understanding the Technology Environment With an understanding of a business procedure, an auditor can then understand how technology is employed to support it. Procedure documentation will often identify existing systems at a high level. To develop an audit program, the audit team needs to “look under the hood.” A PBC list may have been sent to the IT department. Conversations with IT may be required to identify what kind of information they keep on their systems. Possible sources of information include

• Audit documentation Previous audits of different kinds may have documented certain processes within IT. Because of the speed at which many IT environments change, information from an audit a few years back may no longer be relevant.

• Network and system diagrams Information about network and data security can be provided in network diagrams. All network documentation should be dated, and auditors should be sure to inquire about its accuracy and completeness. Diagrams can help an auditor quickly identify areas where they will need a greater depth of information.

• System inventories An IT department may keep a consolidated list of the systems they support. System inventories are performed to different depths and may not contain exactly the information an auditor seeks, but they are often useful tools for drilling into that information. One can review items on the list and inquire as to their relevance to procedures, or identify where a system’s data resides, or whether it is on a standard backup schedule.

• Management’s procedure documentation Management may have formalized certain procedures as part of developing a controlled environment. This information, when available, is often quite useful.

• Disaster recovery plans IT departments may have formalized within disaster recovery plans certain procedures to be performed in the event of an incident. At times these reflect common procedures performed by management. An auditor may find relevant procedure, technology, and controls information from reviewing a disaster recovery plan.

It is important for an auditor to validate understandings based on documentation received from IT personnel.

In addition to being outdated, it is not uncommon for IT documentation to come up short of auditors’ needs. A few examples include the following:

• Documentation may reveal that data entry and processing controls are employed within PeopleSoft, but it might not identify the Linux-hosted Oracle database on the back end, which should be included when testing data security.

• A written description of network security controls might identify the Cisco PIX firewall, but might omit it being used in series with an intrusion prevention system.

These clarifications are important for a test plan to be well designed. It is not uncommon for auditors to sit down with members of IT leadership at this phase to confirm the understanding of key systems and how they are managed.

Changes to IT Environments Technologies and technological procedures change with some regularity. If the auditors learn of changes, they should be sure to address them with client IT personnel. Conversations with IT should address the landscape of current IT projects and review whether they will have an impact on testing controls.

New system implementations must be considered carefully when designing test procedures. When new systems are employed, there are many questions regarding the success of the deployment. Auditors may seek to review life cycle controls employed during a development process to determine if the system’s implementation method introduces control risks. With new systems, there is a risk that documentation was not updated to reflect the use of a new system, or that management shared documentation produced ahead of the system going live. “To-be” documentation could contain claims that certain controls exist that were actually omitted from the production launch.

In addition, it is important to know of systems that are due to be implemented before or during a testing period. These can prove problematic to testing plans, as there could be an interruption or a change in control structures with a new system. For example: An SSAE 16 engagement is testing controls over a long period, typically 12 months. Control objectives are signed off by management ahead of the testing period, and they include performing weekly backups. Four months into the testing period, the IT department upgrades their backup software. In doing so, they change the cycle of backups. This introduces a number of problems:

• Lack of testing evidence The old backup system may have housed records on success and failure of backup jobs. If the system has been retired, records of backup success and failure might no longer be available when auditors request evidence.

• Outdated control objectives Control objectives and control activities might be outdated as documented. The control objective reads that full backups are performed weekly, but the newly implemented practice performs daily incremental backups and full backups only every two weeks. This new practice could fail the stated control objective.

• Outdated controls and control failures The IT department may have encountered problems with the new software performing backups on certain technologies, and may, for a period, fail to perform backups of systems hosted on certain critical servers.

Because of instances such as these, it is important for auditors to be included in communications about potential changes/updates. Without prior knowledge of changes like these, an auditor likely would report failures of control objectives, and client management would argue that failures should not be reported because they have a reasonable controls structure in place. With a full understanding of IT plans, auditors are able to work with the client to accommodate the changes. Appropriate controls language can be used, and coordination with management can be done to ensure the transition does not interfere with the audit.

Controls and Control Objectives Controls are selected for testing because they support a control objective. The control objective is achieved when testing shows tested controls are operating effectively. When building a test plan, auditors organize controls they will test by their support of control objectives.

Controls are implemented to mitigate risks within an organization. Multiple controls often work together to mitigate risks within a process or procedure. The control objective statement summarizes the risk-mitigation goals of controls within a procedure. The control objectives will collectively support the audit’s objectives.

For use in the test plan, control objectives are listed with their supporting controls. This is depicted in the example in Table A-1.

Table A-1 Control Objectives and Their Supporting Controls

Though not all engagements will involve auditors developing lists of control objectives and control activities, many will involve auditors reviewing and providing the client organization feedback on existing controls. Lists like the example in Table A-1 can provide a great deal of assistance to individuals who are new to an audit or new to auditing in general as these lists provide a connection between the individual control activities and the true purpose (or objective) for performing and testing those activities. This can be beneficial in helping to understand the “big picture” of why audits are being performed.

Developing Control Objectives and Supporting Controls When an auditor is tasked with developing the control objectives and the list of controls to test, they must keep the audit’s objectives and scope in mind. It is important that control objectives be properly phrased to both reflect the actual control activities performed by management and support the audit objectives.

When examining existing control objectives and control activities, the auditor should determine if each control activity actually supports the control objective. Control activities can exist within procedures that do not support, or poorly support, the control objective. Any such control activities should be removed from the list. A replacement control may need to be identified so an objective is effectively supported. If an auditor experiences trouble in this area, they should consult upward within their organization.

With the list of supporting controls, the auditor should determine if any of these controls ultimately perform the same function. If two control activities protect against the same problem, the auditor should determine which one should be selected as the key control and remove the other one from the list. An auditor may wish to learn which of these controls can be more efficiently tested before selecting equal controls as key. Management may agree that one of the controls is redundant and elect to cease performing it.

Key Controls and Compensating Controls Compensating controls are valuable to identify during this phase of audit planning. When a control failure occurs, the organization relies on a compensating control, which is a secondary measure that mitigates the same risks addressed by the key control. A good test to determine if a control is a compensating control is whether a failure of the key control is caught by the compensating control.

An example of a key control is a formal request and approval process for provisioning new user access. A request made by an individual’s supervisor with approval by department management is key to ensure an individual’s access levels match their job responsibilities. In the event that access was provisioned outside of the normal process, a periodic (quarterly/annual) review of all user access may provide comfort that user access levels overall are appropriate.

In the event of a control failure of a key control, a compensating control can be considered for testing to determine the materiality of the failure of the key control.

Reviewing Control Objectives and Supporting Controls Over time an organization will change elements of its controls infrastructure. Control structures may evolve due to changes in the organization’s business model, changes in management, or possibly in response to guidance from governing entities, such as how guidance on SOX controls testing now emphasizes a greater focus on governance and monitoring.

When an auditor is tasked with reviewing a control structure, her goal is to make three key determinations:

• Do control activities correctly support management’s activities?

• Do control activities support the control objectives?

• Do the control objectives effectively mitigate risks?