CHAPTER 3

The Audit Process

This chapter discusses the following topics

• Audit management

• ISACA auditing standards and guidelines

• Audit and risk analysis

• Internal controls

• Performing an audit

• Control self-assessments

• Audit recommendations

This chapter covers CISA Domain 1, “The Process of Auditing Information Systems.” The topics in this chapter represent 21 percent of the CISA examination.

The IS audit process is the procedural structure used by auditors to assess and evaluate the effectiveness of the IT organization and how well it supports the organization’s overall goals and objectives. The audit process is backed up by the Information Technology Assurance Framework (ITAF) and the ISACA code of ethics. The ITAF is used to ensure that auditors will take a consistent approach from one audit to the next throughout the entire industry. This will help to advance the entire audit profession and facilitate its gradual improvement over time.

Audit Management

An organization’s audit function should be managed so that an audit charter, strategy, and program can be established; audits performed; recommendations enacted; and auditor independence assured throughout. The audit function should align with the organization’s mission and goals, and work well alongside IT governance and operations.

The Audit Charter

As with any formal, managed function in the organization, the audit function should be defined and described in a charter document. The charter should clearly define roles and responsibilities that are consistent with ISACA audit standards and guidelines, including but not limited to ethics, integrity, and independence. The audit function should have sufficient authority that its recommendations will be respected and implemented, but not so much power that the audit tail will wag the IS dog.

The Audit Program

Audit program is the term used to describe the audit strategy and audit plans that include scope, objectives, resources, and procedures used to evaluate a set of controls and deliver an audit opinion. You could say that an audit program is the plan for conducting audits over a given period.

The term program in audit program is intended to evoke a similar “big picture” point of view as the term program manager does. A program manager is responsible for the performance of several related projects in an organization. Similarly, an audit program is the plan for conducting several audits, types of audits, or audits of varying scope in an organization.

Strategic Audit Planning

The purpose of audit planning is to determine the audit activities that need to take place in the future, including an estimate of the resources (tools, budget, and manpower) required to support those activities.

Factors That Affect an Audit

Like security planning, audit planning must take into account several factors:

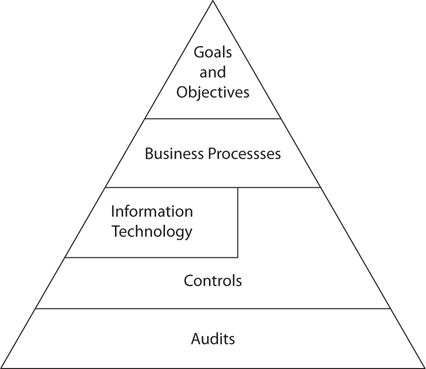

• Organization’s strategic goals and objectives The organization’s overall goals and objectives should flow down to individual departments and their support of these goals and objectives. These goals and objectives will translate into business processes, technology to support business processes, controls for both the business processes and technologies, and audits of those controls. This is depicted in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1 The organization’s goals and objectives translate down into audit activities.

• New organization initiatives Closely related to goals and objectives, organizations often embark on new initiatives, whether new products, new services, or new ways of delivering existing products and services.

• Market conditions Changes in the product or service market may have an impact on auditing. For instance, in a product or services market where security is becoming more important, market competitors could decide to voluntarily undergo audits in order to show that their products or services are safer or better than those from competing organizations. Other market players may need to follow suit for competitive parity. Changes in the supply or demand of supply-chain goods or services can also affect audits.

• Changes in technology Enhancements in the technologies that support business processes may affect business or technical controls, which in turn may affect audit procedures for those controls. Organizations moving their applications or services from on-premise to the cloud is a good example of this.

• Changes in regulatory requirements Changes in technologies, markets, or security-related events can result in new or changed regulations. Maintaining compliance may require changes to the audit program. In the 20-year period preceding the publication of this book, many new information security–related regulations have been passed or updated, including the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the European Data Protection Directive, as well as national and state laws on privacy.

All of the changes listed here usually translate into new business processes or changes in existing business process. Often, this also involves changes to information systems and changes to the controls supporting systems and processes.

Changes in Audit Activities

These external factors may affect auditing in the following ways:

• New internal audits Business and regulatory changes sometimes compel organizations to audit more systems or processes. For instance, after passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, U.S. publicly traded companies had to begin conducting internal audits of those IT systems that support financial business processes.

• New external audits New regulations or competitive pressures could introduce new external audits. For example, virtually all banks and many merchants had to begin undergoing external Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) audits when that standard was established.

• Market competition In certain industries such as financial services, service providers are voluntarily undertaking new audits such as SOC 1 (SSAE 16 in the United States and ISAE 3402 elsewhere), SOC 2, TRUSTe, and ISO/IEC 27001 certification, partly to support marketing claims that their security is superior to that of their competitors’.

• Increase in audit scope The scope of existing internal or external audits could increase to include more processes or systems.

• Impacts on business processes This could take the form of additional steps in processes or procedures, or additions/changes in recordkeeping or record retention.

• Changes in audit standards Also undergoing continuous improvement, general and specific audit rules occasionally change, which might alter sampling methodologies as well as audit procedures. For example, the PCI-DSS 3.0 update requires penetration tests to include network segmentation validation, which can result in significant increases in the time required for penetration testing.

Resource Planning

At least once per year, management needs to consider all of the internal and external factors that affect auditing to determine the resources required to support these activities. Primarily, resources will consist of the budget for external audits and manpower for internal audits.

Additional external audits usually require additional man-hours to meet with external auditors; discuss scope; coordinate meetings with process owners and managers; discuss audits with process owners and managers; discuss audit findings with auditors, process owners, and management; and organize remediation work.

Internal and external audits usually require information systems to track audit activities and store evidence. Taking on additional audit activities may require additional capacity on these systems or new systems altogether.

Additional internal audits require all of the previously mentioned factors, plus time for performing the internal audits themselves. All of these details are discussed in this chapter, and in the rest of this book.

Audit and Technology

ISACA auditing standards require that the auditor retain technical competence. With the continuation of technology and business process innovation, auditors need to continue learning about new technologies, how they support business processes, and how they are controlled. Like many professions, IS auditing requires continuing education to stay current with changes in technology.

Some of the ways that an IS auditor can update their knowledge and skills include

• ISACA training and conferences As the developer of the CISA certification, ISACA offers many valuable training and conference events, including:

• Computer Audit, Control, and Security (CACS) Conference

• Governance, Risk, and Control (GRC) Conference

• Cybersecurity Nexus (CSX) Conference

• ISACA Training Week

• University courses This can include both for-credit and noncredit classes on new technologies. Some universities offer certificate programs on many new technologies; this can give an auditor a real boost of knowledge, skills, and confidence.

• Vo-tech (vocational-technical) training Many organizations offer training in information technologies, including MIS Training Institute, SANS Institute, and ISACA.

• Training webinars These events are usually focused on a single topic and last from one to three hours. ISACA and many other organizations offer training webinars, which are especially convenient since they require no travel and many are offered at no cost.

• ISACA chapter training Many ISACA chapters offer training events so that local members can acquire new knowledge and skills close to where they live.

• Other security association training Many other security-related trade associations offer training, including ISSA (International Systems Security Association), SANS Institute, and IIA (The Institute of Internal Auditors). Training sessions are offered online, in classrooms, and at conferences.

• Security conferences Several security-related conferences include lectures and training. These conferences include those hosted by RSA, SANS, ISSA, Gartner, and SecureWorld Expo. Many local ISACA and ISSA chapters organize local conferences that include training.

Audit Laws and Regulations

Laws and regulations are one of the primary reasons why organizations perform internal and external audits. Regulations on industries generally translate into additional effort on the part of target companies to track their compliance. This tracking takes on the form of internal auditing, and new regulations sometimes also require external audits. And while other factors such as competitive pressures can compel an organization to begin or increase auditing activities, this section discusses laws and regulations that require auditing.

Automation Brings New Regulation

Automating business processes with information systems is still a relatively new phenomenon. Modern businesses have been around for the past two or three centuries, but information systems have been playing a major role in business process automation for only about the past 20 years. Prior to that time, most information systems supported business processes, but only in an ancillary way. Automation of entire business processes is still relatively young, and so many organizations have messed up in such colossal ways that legislators and regulators have responded with additional laws and regulations to make organizations more accountable for the security and integrity of their information systems.

Almost every industry sector is subject to laws and regulations that affect organizations’ use of information and information systems. These laws are concerned primarily with one or more of the following characteristics and uses of information and information systems:

• Security Some information in information systems is valuable and/or sensitive, such as financial and medical records. Many laws and regulations require such information to be protected so that it cannot be accessed by unauthorized parties and require that information systems be free of defects, vulnerabilities, malware, and other threats.

• Integrity Some regulations are focused on the integrity of information to ensure that it is correct and that the systems it resides on are free of vulnerabilities and defects that could make or allow improper changes.

• Privacy Many information systems store information that is considered private. This includes financial records, medical records, and other information about people that they feel should be protected.

Computer Security and Privacy Regulations

This section contains several computer security and privacy laws in the United States, Canada, Europe, and elsewhere. The laws here fall into one or more of the following categories:

• Computer trespass Some of these laws bring the concept of trespass forward into the realm of computers and networks, making it illegal to enter a computer or network unless there is explicit authorization.

• Protection of sensitive information Many laws require that sensitive information be protected, and some include required public disclosures in the event of a breach of security.

• Collection and use of information Several laws define the boundaries regarding the collection and acceptable use of information, particularly private information.

• Offshore data flow Some security and privacy laws place restrictions or conditions on the flow of sensitive data (usually about citizens) out of a country.

• Law enforcement investigative powers Some laws clarify and expand the search and investigative powers of law enforcement.

The consequences of the failure to comply with these laws vary. Some laws have penalties written in as a part of the law; however, the absence of an explicit penalty doesn’t mean there aren’t any! Some of the results of failing to comply include

• Loss of reputation Failure to comply with some laws can make front-page news, with a resulting reduction in reputation and loss of business. For example, if an organization suffers a security breach and is forced to notify customers, word may spread quickly and be picked up by news media outlets, which will help spread the bad news further.

• Loss of competitive advantage An organization that has a reputation for sloppy security may begin to see its business diminish and move to its competitors. A record of noncompliance may also result in difficulty wining new business contracts.

• Government sanctions Breaking many federal laws may result in sanctions from local, regional, or national governments, including losing the right to conduct business.

• Lawsuits Civil lawsuits from competitors, customers, suppliers, and government agencies may be the result of breaking some laws. Plaintiffs may file lawsuits against an organization even if there were other consequences.

• Fines Monetary consequences are frequently the result of breaking laws.

• Prosecution Many laws have criminalized behavior such as computer trespass, stealing information, or filing falsified reports to government agencies. Breaking some laws may result in imprisonment.

Knowledge of these consequences provides an incentive to organizations to develop management strategies to comply with the laws that apply to their business activities. These strategies often result in the development of controls that define required activities and events, plus analysis and internal audit to determine if the controls are effectively keeping the organization in compliance with those laws. While organizations often initially resist undertaking these additional activities, they usually accept them as a requirement for doing business and seek ways of making them more cost-efficient in the long term.

Determining Applicability of Regulations An organization should take a systematic approach to determine the applicability of regulations as well as the steps required to attain compliance with applicable regulations and remain in a compliant state.

Determination of applicability often requires the assistance of legal counsel who is an expert on government regulations, as well as experts in the organization who are familiar with the organization’s practices.

Next, the language in the applicable law or regulation needs to be analyzed and a list of compliant and noncompliant practices identified. These are then compared with the organization’s practices to determine which practices are compliant and which are not. Those practices that are not compliant need to be corrected; one or more accountable individuals need to be appointed to determine what is required to achieve and maintain compliance.

Another approach is to outline the required (or forbidden) practices specified in the law or regulation and then “map” the organization’s relevant existing activities into the outline. Where gaps are found, processes or procedures will need to be developed to bring the organization into compliance.

PCI-DSS: A Highly Effective Non-Law

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) is a data security standard that was developed by a consortium of the major credit card brands: VISA, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and JCB. The major brands have the contractual right to levy fines and impose sanctions, such as the loss of the right to issue credit cards, process payments, or accept credit card payments. PCI-DSS has gotten a lot of attention, and by many accounts it has been more effective than many state and national laws.

Regulations Not Always Clear

Sometimes, the effort to determine what’s needed to achieve compliance is substantial. For instance, when the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was signed into law, virtually no one knew exactly what companies had to do to achieve compliance. Guidance from the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board was not published for almost a year. It took another two years before audit firms and U.S. public companies were familiar and comfortable with the necessary approach to achieve compliance with the act.

U.S. Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards applicable in the United States include

• Privacy Act of 1974

• Access Device Fraud, 1984

• Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1984

• Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986

• Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act of 1988

• Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994

• Economic and Protection of Proprietary Information Act of 1996

• Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996

• Economic Espionage Act (EEA), 1996

• No Electronic Theft (NET) Act, 1997

• Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), 1998

• Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998

• Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 1998

• Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) of 1999

• Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), an agency with legally binding standards

• Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001 (expired in 2015, succeeded by the USA Freedom Act)

• Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002

• Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) of 2002

• Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act of 2003

• California privacy law SB 1386 of 2003

• Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act of 2003

• Basel II, 2004, an international accord

• Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), 2004; updated 2016

• North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), 1968/2006, an agency with legally binding standards

• Massachusetts security breach law, 2007

• Red Flags Rule, 2008

• Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) of 2009

• USA Freedom Act, 2015

Canadian Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards in Canada include

• Interception of Communications (Section 184 of the Canada Criminal Code)

• Unauthorized Use of Computer (Section 342.1 of the Canada Criminal Code)

• Privacy Act, 1983

• Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), 2000

• Digital Privacy Act, 2015

European Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards from Europe include

• Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, 1981, Council of Europe

• Computer Misuse Act (CMA), 1990, UK

• Directive on the Protection of Personal Data (95/46/EC), 2003, European Union

• Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998, UK

• Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000, UK

• Anti-Terrorism, Crime, and Security Act 2001, UK

• Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations 2003, UK

• Fraud Act 2006, UK

• Police and Justice Act 2006, UK

• European Data Protection Directive, 2016

Other Regulations Selected security and privacy laws and standards from the rest of the world include

• Cybercrime Act, 2001, Australia

• Information Technology Act, 2000, India

ISACA Auditing Standards

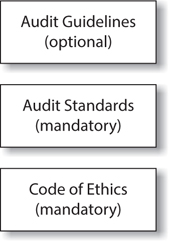

(ISACA has published its Information Technology Assurance Framework in the ITAF: A Professional Practices Framework for IS Audit/Assurance (currently in its third edition and available free of charge at www.isaca.org/ITAF). ITAF consists of the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics, IS audit and assurance standards, IS audit and assurance guidelines, and IS audit and assurance tools and techniques. This section discusses the Code of Professional Ethics, standards, and guidelines. The relationship between these is illustrated in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2 Relationship between ISACA audit standards, audit guidelines, and Code of Professional Ethics

ISACA Code of Professional Ethics

Like many professional associations, ISACA has published a Code of Professional Ethics. The purpose of the code is to define principles of professional behavior that are based on the support of standards, compliance with laws and standards, and the identification and defense of the truth.

Audit and IT professionals who earn the CISA certification are required to sign a statement that declares their support of the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics. If someone who holds the CISA certification is found to be in violation of the code, he or she may be disciplined and possibly lose his or her certification. The full text of the ISACA Code of Professional Ethics can be found at www.isaca.org/ethics.

ISACA Audit and Assurance Standards

The ISACA audit and assurance standards framework, known as the Information Technology Assurance Framework (ITAF) defines minimum standards of performance related to security, audits, and the actions that result from audits. This section lists the standards and paraphrases each.

The full text of these standards is available at www.isaca.org/standards.

1001, Audit Charter

Audit activities in an organization should be formally defined in an audit charter. This should include statements of scope, responsibility, and authority for conducting audits. Senior management should support the audit charter through direct signature or by linking the audit charter to corporate policy.

1002, Organizational Independence

The IS auditor’s placement in the command-and-control structure of the organization should ensure that the IS auditor can act independently.

1003, Professional Independence

Behavior of the IS auditor should be independent of the auditee. The IS auditor should take care to avoid even the appearance of impropriety.

1004, Reasonable Expectation

IS auditors and assurance professionals shall have a reasonable expectation that an audit engagement can be completed according to ISACA and other audit standards, that the audit scope enables completion of the audit, and that management understands its obligations and responsibilities.

1005, Due Professional Care

IS auditors and assurance professionals shall exercise due professional care, including but not limited to conformance with applicable audit standards.

1006, Proficiency

IS auditors and assurance professionals shall possess adequate skills and knowledge on the performance of IS audits and of the subject matter being audited, and shall continue in their proficiency through regular continuing professional education and training.

1007, Assertions

IS auditors and assurance professionals shall review audit assertions to determine whether they are capable of being audited, and whether the assertions are valid and reasonable.

1008, Criteria

IS auditors and assurance professionals shall select objective, measurable, and reasonable audit criteria.

1201, Engagement Planning

IS auditors shall perform audit planning work to ensure that the scope and breadth of an audit is sufficient to meet the organization’s needs, that it is in compliance with applicable laws, and that it is risk based.

1202, Risk Assessment in Planning

The IS auditor should use a risk-based approach when making decisions about which controls and activities should be audited and the level of effort expended in each audit. These decisions should be documented in detail to avoid any appearance of partiality.

A risk-based approach looks not only at security risks, but at overall business risk. This will probably include operational risk and may include aspects of financial risk.

1203, Performance and Supervision

IS auditors shall conduct an audit according to the plan and on schedule; shall supervise audit staff; shall accept and perform audit tasks only within their competency; and shall collect appropriate evidence, document the audit process, and document findings.

1204, Materiality

The IS auditor should consider materiality when prioritizing audit activities and allocating audit resources. During audit planning, the auditor should consider whether ineffective controls or an absence of controls could result in a significant deficiency or material weakness.

In addition to auditing individual controls, the auditor should consider the effectiveness of groups of controls and determine if a failure across a group of controls would constitute a significant deficiency or material weakness. For example, if an organization has several controls regarding the management and control of third-party service organizations, failures in many of those controls could represent a significant deficiency or material weakness overall.

1205, Evidence

The IS auditor should gather sufficient evidence to develop reasonable conclusions about the effectiveness of controls and procedures. The IS auditor should evaluate the sufficiency and integrity of audit evidence, and this evaluation should be included in the audit report.

Audit evidence includes the procedures performed by the auditor during the audit, the results of those procedures, source documents and records, and corroborating information. Audit evidence also includes the audit report.

1206, Using the Work of Other Experts

An IS auditor should consider using the work of other auditors when and where appropriate. Whether an auditor can use the work of other auditors depends on several factors, including:

• The relevance of the other auditors’ work

• The qualifications and independence of the other auditors

• Whether the other auditors’ work is adequate (this will require an evaluation of at least some of the other auditors’ work)

• Whether the IS auditor should develop additional test procedures to supplement the work of another auditor(s)

If an IS auditor uses another auditor’s work, his report should document which portion of the audit work was performed by the other auditor, as well as an evaluation of that work.

1207, Irregularity and Illegal Acts

IS auditors should have a healthy but balanced skepticism with regard to irregularities and illegal acts: The auditor should recognize that irregularities and/or illegal acts could be ongoing in one or more of the processes that he is auditing. He should recognize that management may or may not be aware of any irregularities or illegal acts.

The IS auditor should obtain written attestations from management that state management’s responsibilities for the proper operation of controls. Management should disclose to the auditor any knowledge of irregularities or illegal acts.

If the IS auditor encounters material irregularities or illegal acts, he should document every conversation and retain all evidence of correspondence. The IS auditor should report any matter of material irregularities or illegal acts to management. If material findings or irregularities prevent the auditor from continuing the audit, the auditor should carefully weigh his options and consider withdrawing from the audit. The IS auditor should determine if he is required to report material findings to regulators or other outside authorities. If the auditor is unable to report material findings to management, he should consider withdrawing from the audit engagement.

1401, Reporting

The IS auditor should develop an audit report that documents the process followed, inquiries, observations, evidence, findings, conclusions, and recommendations from the audit. The audit report should follow an established format that includes a statement of scope, period of coverage, recipient organization, controls or standards that were audited, and any limitations or qualifications. The report should contain sufficient evidence to support the findings of the audit.

1402, Follow-up Activities

After the completion of an audit, the IS auditor should follow up at a later time to determine if management has taken steps to make any recommended changes or apply remedies to any audit findings.

ISACA Audit and Assurance Guidelines

ISACA audit and assurance guidelines contain information that helps the auditor understand how to apply ISACA audit standards. These guidelines are a series of articles that clarify the meaning of the audit standards. They cite specific ISACA IS audit standards and COBIT controls, and provide specific guidance on various audit activities. ISACA audit guidelines also provide insight into why each guideline was developed and published.

The full text of these guidelines is available at www.isaca.org/guidelines.

2001, Audit Charter

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Mandate

• Contents of the audit charter

2002, Organizational Independence

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Position in the enterprise

• Reporting level

• Non-audit services

• Assessing independence

• Audit charter and audit plan

2003, Professional Independence

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Conceptual framework

• Threats and safeguards

• Managing threats

• Non-audit services or roles that do not impair independence

• Non-audit services or roles that do impair independence

• Relevance of independence when providing non-audit services or roles

• Governance of the admissibility of non-audit services or roles

• Reporting

2004, Reasonable Expectation

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Standards and regulations

• Scope

• Scope limitations

• Information

• Acceptance of a change in engagement terms

2005, Due Professional Care

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Professional skepticism and competency

• Application

• Life cycle of the engagement

• Communication

• Managing information

2006, Proficiency

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Professional competence

• Evaluation

• Reaching the desired level of competence

2007, Assertions

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Assertions

• Subject matter and criteria

• Assertions developed by third parties

• Conclusion and report

2008, Criteria

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Selection and use of criteria

• Suitability

• Acceptability

• Source

• Change in criteria during the audit engagement

2201, Engagement Planning

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• IS audit plan

• Objectives

• Scope and business knowledge

• Risk-based approach

• Documenting the audit engagement project plan

• Changes during the course of the audit

2202, Risk Assessment in Planning

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Risk assessment of the IS audit plan

• Risk assessment methodology

• Risk assessment of individual audit engagements

• Audit risk

• Inherent risk

• Control risk

• Detection risk

2203, Performance and Supervision

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Performing the work

• Roles and responsibilities, knowledge and skills

• Supervision

• Evidence

• Documenting

• Findings and conclusions

2204, Materiality

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• IS vs. financial audit engagements

• Assessing materiality of the subject matter

• Materiality and controls

• Materiality and reportable issues

2205, Evidence

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Types of evidence

• Obtaining evidence

• Evaluating evidence

• Preparing audit documentation

2206, Using the Work of Other Experts

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Considering the use of work of other experts

• Assessing the adequacy of other experts

• Planning and reviewing the work of other experts

• Evaluating the work of other experts who are not part of the audit engagement team

• Additional test procedures

• Audit opinion or conclusion

2207, Irregularity and Illegal Acts

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Irregularities and illegal acts

• Responsibilities of management

• Responsibilities of the professionals

• Irregularities and illegal acts during engagement planning

• Designing and reviewing engagement procedures

• Responding to irregularities and illegal acts

• Internal reporting

• External reporting

2208, Audit Sampling

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Sampling

• Design of the sample

• Selection of the sample

• Evaluation of sample results

• Documentation

2401, Reporting

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Types of engagements

• Required contents of the audit engagement report

• Subsequent events

• Additional communication

2402, Follow-up Activities

This guideline provides information on the following IS audit standards topics:

• Follow-up process

• Management’s proposed actions

• Assuming the risk of not taking corrective action

• Follow-up procedures

• Timing and scheduling of follow-up activities

• Nature and extent of follow-up activities

Relationship Between Standards and Guidelines

The ISACA audit standards and guidelines have been written to assist IS auditors with audit- and risk-related activities. They are related to each other in this way:

• Standards are statements that all IS auditors are expected to follow, and they can be considered a rule of law for auditors.

• Guidelines are statements that help IS auditors better understand how ISACA standards can be implemented.

The ISACA Code of Professional Ethics encompasses the standards and guidelines through the requirement of proper professional behavior.

• Deferring follow-up activities

• Form of follow-up responses

• Follow-up by professionals on external audit recommendations

• Reporting of follow-up activities

Risk Analysis

In the context of an audit, risk analysis is the activity that is used to determine the areas that warrant additional examination and analysis.

In the absence of a risk analysis, an IS auditor is likely to follow his or her “gut instinct” and apply additional scrutiny in areas where they feel risks are higher. Or, an IS auditor might give all areas of an audit equal weighting, putting equal resources into low-risk areas and high-risk areas. Either way, the result is that an IS auditor’s focus is not necessarily on the areas where risks really are higher. This results in a disservice to the audit client.

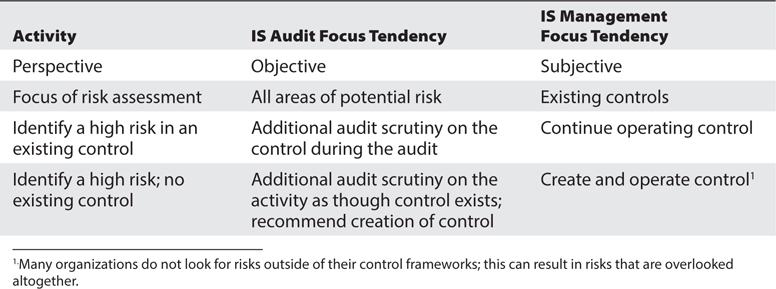

Auditors’ Risk Analysis and the Corporate Risk Management Program

A risk analysis that is carried out by IS auditors is distinct and separate from risk analysis that is performed as part of the corporate risk management program. Often, these risk analyses are carried out by different personnel and for somewhat differing reasons. A comparison of IS auditor and IS management risk analysis is shown in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1 Comparison of IS Audit and IS Management Risk Analysis

In Table 3-1, I am not attempting to show a polarity of focus and results, but instead a tendency for focus based on the differing missions and objectives of IS audit and IS management.

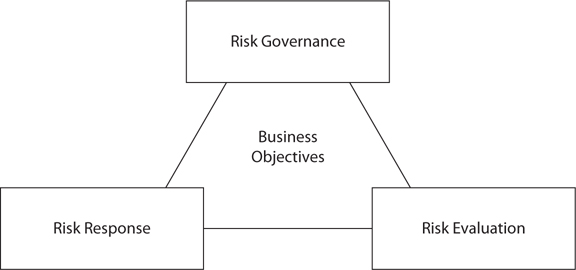

The ISACA Risk IT Framework

Auditors’ risk analysis and corporate risk management can both be performed using the ISACA Risk IT Framework. This framework, which is depicted in Figure 3-3, approaches risk from the enterprise perspective, encompassing all types of business risk, including IT risk.

Figure 3-3 The ISACA Risk IT Framework high-level components

The Risk IT Framework consists of three major activities:

• Risk governance The purpose of risk governance is to ensure that IT risk is integrated into the organization’s enterprise risk management (ERM) program.

• Risk evaluation The purpose of risk evaluation is to provide a framework of processes for performing risk assessments against business assets and explained in business terms.

• Risk response The purpose of risk response is to provide a framework of processes for responding to identified risks through reporting and risk treatment.

Like other business frameworks, the Risk IT Framework contains detailed top-down explanations of business processes and includes references to COBIT, ISACA audit standards, and Val IT—another ISACA framework concerned with achieving business value from IT investments.

The Risk IT Framework is available from ISACA at www.isaca.org/riskit.

Evaluating Business Processes

The first phase of a risk analysis is an evaluation of business processes. The purpose of evaluating business processes is to determine the purpose, importance, and effectiveness of business activities. While parts of a risk analysis may focus on technology, remember that technology exists to support business processes, not the other way around.

When a risk analysis starts with a focus on business processes, it is appropriate to consider the entire process and not just the technology that supports it. When examining business processes, it is important to obtain all available business process documentation, including:

• Charter or mission statement Often, an organization will develop and publish a high-level document that describes the process in its most basic terms. This usually includes the reason that the process exists and how it contributes to the organization’s overall goals and objectives.

• Process architecture A complex process may have several procedures, flows of information (whether in electronic form or otherwise), internal and external parties that perform functions, assets that support the process, and the locations and nature of records. In a strictly IT-centric perspective, this would be a data flow diagram or an entity-relationship diagram, but starting with either of those would be too narrow a focus. Instead, it is necessary to look at the entire process, with the widest view of its functions and connections with other processes and parties.

• Procedures Looking closer at the process will reveal individual procedures—documents that describe the individual steps taken to perform activities that are part of the overall process. Procedure documents usually describe who (if not by name, then by title or department) performs what functions with what tools or systems. Procedures will cite business records that might be faxes, reports, databases, phone records, application transactions, and so on.

• Records Business records contain the events that take place within a business process. Records will take many forms, including faxes, computer reports, electronic worksheets, database transactions, receipts, canceled checks, and e-mail messages.

• Information system support When processes are supported by information systems, it is necessary to examine all available documents that describe information systems that support business processes. Examples of documentation are architecture diagrams, requirements documents (which were used to build, acquire, or configure the system), computer-run procedures, network diagrams, database schemas, and so on.

In addition to reviewing documentation, it is essential that personnel involved with each process be interviewed, so that they can describe their understanding of the process, its procedures, and other relevant details. The auditor can then compare descriptions from individuals with details in process and procedure documents. This will help the auditor understand the degree to which processes and procedures are performed consistently and in harmony with documentation.

Once the IS auditor has obtained business documents and interviewed personnel, she can begin to identify and understand any risk areas that may exist in the process.

Identifying Business Risks

The process of identifying business risks is partly analytical and partly based on the auditor’s experience and judgment. An auditor will usually consider both within the single activity of risk identification.

An auditor will usually perform a threat analysis to identify and catalog risks. A threat analysis is an activity whereby the auditor considers a large body of possible threats and selects those that have some reasonable possibility of occurrence, however small. In a threat analysis, the auditor will consider each threat and document a number of facts about each, including:

• Probability of occurrence This may be expressed in qualitative (high, medium, low) or quantitative (percentage or number of times per year) terms. The probability should be as realistic as possible, recognizing the fact that actuarial data on business risk is difficult to obtain and more difficult to interpret. Here, an experienced auditor’s judgment is required to establish a reasonable probability.

• Impact This is a short description of the results if the threat is actually realized. This is usually a short description, from a few words to a couple of sentences.

• Loss This is usually a quantified and estimated loss should the threat actually occur. This figure might be a loss of revenue per day (or week or month) or the replacement cost for an asset, for example.

• Possible mitigating controls This is a list of one or more countermeasures that can reduce the probability or the impact of the threat, or both.

• Countermeasure cost and effort The cost and effort to implement each countermeasure should be identified, either with a high-medium-low qualitative figure or a quantitative estimate.

• Updated probability of occurrence With each mitigating control, a new probability of occurrence should be cited. A different probability, one for each mitigating control, should be specified.

• Updated impact With each mitigating control, a new impact of occurrence should be described. For certain threats and countermeasures, the impact may be the same, but for some threats, it may be different. For example, for a threat of fire, a mitigating control may be an inert gas fire suppression system. The new impact (probably just downtime and cleanup) will be much different from the original impact (probably water damage from a sprinkler system).

The auditor will put all of this information into a chart (or electronic spreadsheet) to permit further analysis and the establishment of conclusions—primarily, which threats are most likely to occur and which ones have the greatest potential impact on the organization.

Since it is not the role of auditors to suggest solutions to risks, auditors sometimes forego the analysis of countermeasures. A more likely outcome is the identification of high-risk controls that warrant additional audit scrutiny.

Risk Mitigation

The actual mitigation of risks addressed in the risk assessment is the implementation of one or more of the countermeasures identified in the risk assessment. In simple terms, mitigation could be as easy as a small adjustment in a process or procedure, or a major project to introduce new controls in the form of system upgrades, new components, or new procedures.

When the IS auditor is conducting a risk analysis prior to an audit, risk mitigation may take the form of additional audit scrutiny on certain activities during the audit. Such subsequent analysis will give the IS auditor additional insight about the effectiveness of high-risk controls: a control that the auditor identified as high risk could end up performing well, while other, lower-risk activities could actually be the cause of control failures.

Additional audit scrutiny could take several forms, including one or more of the following:

• More time spent in inquiry and observation

• More personnel interviews

• Higher sampling rates

• Additional tests

• Re-performance of some control activities to confirm accuracy or completeness

• Corroboration interviews

Countermeasures Assessment

Depending upon the severity of the risk, mitigation could also take the form of additional (or improved) controls, even prior to (or despite the results of) the audit itself. The new or changed control may be major or minor, and the time and effort required to implement it could range from almost trivial to a major project.

The cost and effort required to implement a new control (or whatever the countermeasure is that is designed to reduce the probability or impact of a threat) should be determined before it is implemented. It probably does not make sense to spend $10,000 to protect an asset worth $100—unless, of course, there was considerable organizational reputation also associated with that $100 asset.

Monitoring

After countermeasures are implemented, the IS auditor will need to reassess the controls through additional testing. If the control includes any self-monitoring or measuring, the IS auditor should examine those records to see if there is any visible effect of the countermeasures.

The auditor may need to repeat audit activities to determine the effectiveness of countermeasures. For example, additional samples selected after the countermeasure is implemented can be examined and the rate of exceptions compared to periods prior to the countermeasure’s implementation.

Controls

The policies, procedures, mechanisms, systems, and other measures designed to reduce risk are known as controls. An organization develops controls to ensure that its business objectives will be met, risks will be reduced, and errors will be prevented or corrected.

Controls are used in two primary ways in an organization: they are created to ensure desired events, and they are created to avoid unwanted events.

Control Classification

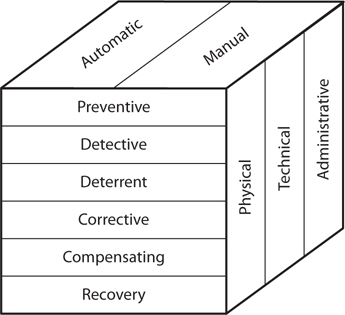

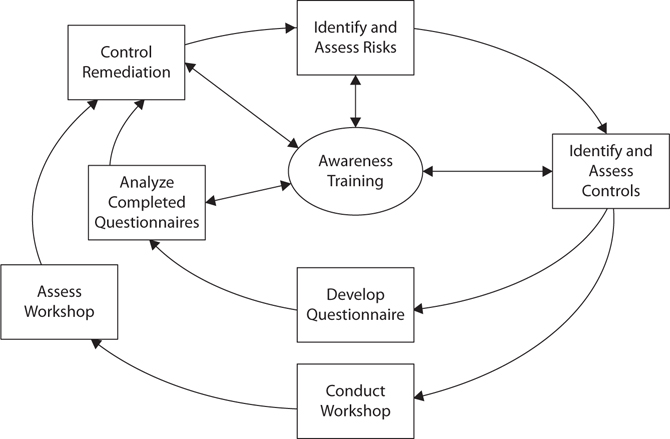

Several types, classes, and categories of controls are discussed in this section. Figure 3-4 depicts this control classification.

Figure 3-4 Control classification shows types, classes, and categories of controls.

Types of Controls

The three types of controls are physical, technical, and administrative:

• Physical These types of controls exist in the tangible, physical world. Examples of physical controls are video surveillance, bollards, and fences.

• Technical These controls are implemented in the form of information systems and are usually intangible. Examples of technical controls include encryption, computer access controls, and audit logs. These are also referred to sometimes as logical controls.

• Administrative These controls are the policies and procedures that require or forbid certain activities. An example administrative control is a policy that forbids personal use of information systems. These are also referred to sometimes as managerial controls.

Classes of Controls

There are six classes of controls:

• Preventive This type of control is used to prevent the occurrence of an unwanted event. Examples of preventive controls are computer login screens (which prevent unauthorized persons from accessing information), keycard systems (which prevent unauthorized persons from entering a building or workspace), and encryption (which prevent persons lacking an encryption key from reading encrypted data).

• Detective This type of control is used to record both wanted and unwanted events. A detective control cannot enforce an activity (whether it is desired or undesired), but instead it can only make sure that it is known whether, and how, the event occurred. Examples of detective controls include video surveillance and audit logs.

• Deterrent This type of control exists in order to convince someone that they should not perform some unwanted activity. Examples of deterrent controls include guard dogs, warning signs, and visible video surveillance cameras and monitors.

• Corrective This type of control is activated (manually or automatically) after some unwanted event has occurred. An example corrective control is the act of improving a process when it was found to be defective.

• Compensating This type of control is enacted because some other direct control cannot be used. For example, a video surveillance system can be a compensating control when it is implemented to compensate for the lack of a stronger detective control, such as a keycard access system. A compensating control addresses the risk related to the original control.

• Recovery This type of control is used to restore the state of a system or asset to its pre-incident state. An example recovery control is the use of a tool to remove a virus from a computer.

Auditors need to understand one key difference between preventive and deterrent controls. A deterrent control requires knowledge of the control by the potential violator—it only works if they know it exists. A preventive control works regardless of whether or not the violator is aware of it.

Categories of Controls

There are two categories of controls:

• Automatic This type of control performs its function with little or no human judgment or decision-making. Examples of automatic controls include a login page on an application that cannot be circumvented, and a security door that automatically locks after someone walks through the doorway.

• Manual This type of control requires a human to operate it. A manual control may be subject to a higher rate of errors than an automatic control. An example of a manual control is a monthly review of computer users.

Internal Control Objectives

Internal control objectives are statements of desired states or outcomes from business operations. Example control objectives include

• Protection of IT assets

• Accuracy of transactions

• Confidentiality and privacy

• Availability of IT systems

• Controlled changes to IT systems

• Compliance with corporate policies

Control objectives are the foundation for controls. For each control objective, one or more controls will exist to ensure the realization of the control objective. For example, the “Availability of IT Systems” control objective will be met with several controls, including

• IT systems will be continuously monitored, and any interruptions in availability will result in alerts sent to appropriate personnel.

• IT systems will have resource-measuring capabilities.

• IT management will review capacity reports monthly and adjust resources accordingly.

• IT systems will have anti-malware controls that are monitored by appropriate staff.

Together, these four (or more) controls contribute to the overall control objective on IT system availability. Similarly, the other control objectives will have one or more controls that will ensure their realization.

IS Control Objectives

IS control objectives resemble ordinary control objectives but are set in the context of information systems. Examples of IS control objectives include

• Protection of information from unauthorized personnel

• Protection of information from unauthorized modification

• Integrity of operating systems

• Controlled and managed changes to information systems

• Controlled and managed development of application software

An organization will probably have several additional IS control objectives on other basic topics such as malware, availability, and resource management.

Like ordinary control objectives, IS control objectives will be supported by one or more controls.

The COBIT 5 Controls Framework

To ensure that IT is aligned with business objectives, the COBIT 5 controls framework of five principles and 37 processes is an industry-wide standard. The five principles are

• Meeting Stakeholder Needs

• Covering the Enterprise End-to-End

• Applying a Single, Integrated Framework

• Enabling a Holistic Approach

• Separating Governance from Management

COBIT 5 contains more than 1100 control activities to support these principles.

Established in 1996 by ISACA and the IT Governance Institute, COBIT is the result of industry-wide consensus by managers, auditors, and IT users. Today, COBIT 5 is accepted as a best-practices IT process and control framework.

Starting with Version 5, COBIT has absorbed ISACA’s Risk IT Framework and Val IT Framework.

General Computing Controls

An IS organization supporting many applications and services will generally have some controls that are specific to each individual application. However, IS will also have a set of controls that apply across all of its applications and services. These are usually called its general computing controls, or GCCs.

An organization’s GCCs are general in nature and are often implemented in different ways on different information systems, based upon their individual capabilities and limitations, as well as applicability. Examples of GCCs include

• Applications require unique user IDs and strong passwords.

• Passwords are encrypted while stored and transmitted, and are not displayed.

• Highly sensitive information, such as bank account numbers, is encrypted when stored and transmitted.

• All administrative actions are logged, and logs are protected from tampering.

Readers who are familiar with information systems technology will quickly realize that these GCCs will be implemented differently across different types of information systems. Specific capabilities and limitations, for example, will result in somewhat different capabilities for password complexity and data encryption. Unless an organization is using really old information systems, the four GCCs shown here can probably be implemented everywhere in an IS environment. How they are implemented is the subject of the next section.

IS Controls

The GCCs discussed in the previous section are implemented across a variety of information technologies. Each general computing control is mapped to a specific IS control on each system type, where it is implemented. In other words, IS controls describe the implementation details for GCCs.

For example, a GCC for password management can be implemented through several IS controls—one for each type of technology platform in use in the organization: one for Windows servers, one for Linux servers, and one for each application that performs its own access management. Those specific IS controls would describe implementation details that reflect the capabilities and limitations of each respective platform.

Performing an Audit

An audit is a systematic and repeatable process whereby a competent and independent professional evaluates one or more controls, interviews personnel, obtains and analyzes evidence, and develops a written opinion on the effectiveness of the control(s).

An IS audit, then, is an audit of information systems and the processes that support them. An IS auditor interviews personnel, gathers and analyzes evidence, and delivers a written opinion on the effectiveness of controls implemented in information systems.

An auditor cannot just begin an audit. Rather, audits need to be planned events. Formal planning is required that includes

• Purpose The IS auditor and the auditee must establish a reason why an audit is to be performed. The purpose for a particular audit could be to determine the level of compliance to a particular law, regulation, standard, or contract. Another reason could be to determine whether specific control deficiencies identified in past audits have been remediated. Still another reason is to determine the level of compliance to a new law or standard that the organization may be subject to in the future.

• Scope The auditor and the auditee must also establish the scope of the audit. Often, the audit’s purpose will make the scope evident, but not always. Scope may be multidimensional: it could be a given period, meaning records spanning a start date and end date may comprise the body of evidence, geography (systems in a particular region or locale), technology (systems using a specific operating system, database, application, or other aspect), business process (systems that support specific processes such as accounting, order entry, or customer support), or segment of the organization.

• Risk analysis To know which areas require the greatest amount of attention, the IS auditor needs to be familiar with the levels of risk associated with the domain being audited. Two different perspectives of risk may be needed: First, the IS auditor needs to know the relative levels of risk among the different aspects of the domain being audited so that audit resources can be allocated accordingly. For example, if the audit is on an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and the auditor knows that the accounts receivable function has been problematic in the past, the IS auditor will probably want to devote more resources and time on the accounts receivable function than on others. Second, the IS auditor needs to know about the absolute level of risk across the entire domain being audited. For example, if this is an audit to determine compliance to new legislation, the overall risk could be very high if the consequences of noncompliance are high. Both aspects of risk enable the IS auditor to plan accordingly.

• Audit procedures The purpose and scope of the audit may help to define the procedures that will be required to perform the audit. For a compliance audit, for example, there may be specific rules on sample sizes and sampling techniques, or it may require auditors with specific qualifications to perform the audit. A compliance audit may also specify criteria for determining if a particular finding constitutes a deficiency or not. There may also be rules for materiality.

• Resources The IS auditor must determine what resources are needed and available for the audit. In an external audit, the auditee (which is a client organization) may have a maximum budget figure available. For an external or internal audit, the IS auditor needs to determine the number of man-hours that will be required in the audit and the various skills required. Other resources that may be needed include specialized tools to gather or analyze information obtained from information systems—for example, an analysis program to process the roles and permissions in a database management system in order to identify high-risk areas. To a great degree, the purpose and scope of the audit will determine which resources are required to complete it.

• Schedule The IS auditor needs to develop an audit schedule that will give enough time for interviews, data collection and analysis, and report generation. However, the schedule could also come in the form of a constraint, meaning the audit must be complete by a certain date. If the IS auditor is given a deadline, he will need to see how the audit activities can be made to fit within that period. If the date is too aggressive, the IS auditor will need to discuss the matter with the auditee to make required adjustments in scope, resources, or schedule.

Appendix A is devoted to a pragmatic approach to conducting professional audits.

Audit Objectives

The term audit objectives refers to the specific goals for an audit. Generally, the objective of an audit is to determine if controls exist and are effective in some specific aspect of business operations in an organization. Generally an audit is performed as a part of regulations, compliance, or legal obligations. It may also be performed as the result of a serious incident or event.

Depending on the subject and nature of the audit, the auditor may examine the controls and related evidence herself, or the auditor may instead focus on the business content that is processed by the controls. In other words, if the focus of an audit is an organization’s accounting system, the auditor may focus on financial transactions in the system to see how they affect financial bookkeeping. Or, the auditor could focus on the IS processes that support the operation of the financial accounting system. Formal audit objectives should make such a distinction so that the auditor has a sound understanding of the objectives. This tells the auditor what to look at during the audit. Of course, the type of audit being undertaken helps too; this is covered in the next section.

Types of Audits

The scope, purpose, and objectives of an audit will determine the type of audit that will be performed. IS auditors need to understand each type of audit, including the procedures that are used for each:

• Operational audit This type of audit is an examination of IS controls, security controls, or business controls to determine control existence and effectiveness. The focus of an operational audit is usually the operation of one or more controls, and it could concentrate on the IS management of a business process or on the business process itself. The scope of an operational audit is shaped to meet audit objectives.

• Financial audit This type of audit is an examination of the organization’s accounting system, including accounting department processes and procedures. The typical objective of a financial audit is to determine if business controls are sufficient to ensure the integrity of financial statements.

• Integrated audit This type of audit combines an operational audit and a financial audit in order for the auditor to gain a complete understanding of the entire environment’s integrity. Such an audit will closely examine accounting department processes, procedures, and records, as well as the IS applications that support the accounting department. Virtually every organization uses a computerized accounting system for management of its financial records; the computerized accounting system and all of the supporting infrastructure (database management system, operating system, networks, workstations, and so on) will be examined to see if the IS department has the entire environment under adequate control.

• IS audit This type of audit is a detailed examination of most or all of an IS department’s operations. An IS audit looks at IT governance to determine if IS is aligned with overall organization goals and objectives. The audit also looks closely at all of the major IS processes, including service delivery, change and configuration management, security management, systems development life cycle, business relationship and supplier management, and incident and problem management. This audit will determine if each control objective and control is effective and operating properly.

• Administrative audit This type of audit is an examination of operational efficiency within some segment of the organization.

• Compliance audit This type of audit is performed to determine the level and degree of compliance to a law, regulation, standard, or internal control. If a particular law or standard requires an external audit, the compliance audit may have to be performed by approved or licensed external auditors; for example, a U.S. public company financial audit must be performed by a public accounting firm, and a PCI audit must be performed by a licensed QSA (qualified security assessor). If, however, the law or standard does not explicitly require audits, the organization may still wish to perform one-time or regular audits to determine the level of compliance to the law or standard. This type of audit may be performed by internal or external auditors, and typically is performed so that management has a better understanding of the level of compliance risk.

• Forensic audit This type of audit is usually performed by an IS auditor or a forensic specialist in support of an anticipated or active legal proceeding. In order to withstand cross-examination and to avoid having evidence being ruled inadmissible, strict procedures must be followed in a forensic audit, including the preservation of evidence and a chain of custody of evidence.

• Service provider audit Because many organizations outsource critical activities to third parties, often these third-party service organizations will undergo one or more external audits in order to increase customer confidence in the integrity of the third-party organization’s services. In the United States, a Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements No. 16, Reporting on Controls at a Service Organization (SSAE 16) can be performed on a service provider’s operations and the audit report transmitted to customers of the service provider. SSAE 16 superseded the Statement of Accounting Standards No. 70 (SAS 70) audit in 2011. The SSAE 16 standard was developed by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) for the purpose of auditing third-party service organizations that perform financial services on behalf of their customers.

Internal and External Audits

The terms internal audit and external audit refer only to the relationship between auditor and auditee, and not to the types of audits discussed in this section.

• Internal audit This is an audit performed by personnel employed by the auditee organization. Internal auditors typically still have a degree of independence through their locations on the org chart.

• External audit This is an audit performed by auditors who are not employees of the auditee. Typically, external auditors are employees of an audit firm.

There is, of course, some gray area here: in a large organization such as a holding company, auditors who are employees of the holding company may be considered as external auditors to the auditee.

• Pre-audit While not technically an audit, a pre-audit is an examination of business processes, IS systems, and business records in anticipation of an upcoming external audit. Usually, an organization will undergo a pre-audit in order to get a better idea of its compliance to a law, regulation, or standard prior to an actual compliance audit. An organization can use the results of a pre-audit to implement corrective measures, thereby improving the outcome of the real audit.

Compliance vs. Substantive Testing

It is important for IS auditors to understand the distinction between compliance testing and substantive testing. These two types of testing are defined here:

• Compliance testing This type of testing is used to determine if control procedures have been properly designed and implemented, and are operating properly. For example, an IS auditor might examine business processes, such as the systems development life cycle, change management, or configuration management, to determine if information systems environments are properly managed.

• Substantive testing This type of testing is used to determine the accuracy and integrity of transactions that flow through processes and information systems. For instance, an IS auditor may create test transactions and trace them through the environment, examining them at each stage until their completion.

IS audits sometimes involve both compliance testing and substantive testing. The audit objectives that are established will determine if compliance testing, substantive testing, or both will be required.

Audit Methodology

An audit methodology is the set of audit procedures that is used to accomplish a set of audit objectives. An organization that regularly performs audits should develop formal methodologies so that those audits are performed consistently, even when carried out by different personnel.

The phases of a typical audit methodology are described in the remainder of this section.

Audit Subject

Determine the business process, information system, or other domain to be audited. For instance, an IS auditor might be auditing an IT change control process, an IT service desk ticketing system, or the activities performed by a software development department.

Audit Objective

Identify the purpose of the audit. For example, this may be an audit that is required by a law, regulation, standard, or business contract. Or this may be an audit to determine compliance with internal control objectives to measure control effectiveness.

Type of Audit

Identify the type of audit that is to be performed. This may be an operational audit, financial audit, integrated audit, administrative audit, compliance audit, forensic audit, or a security provider audit.

Audit Scope

The business process, department, or application that is the subject of the audit needs to be identified. Usually, a span of time needs to be identified as well so that activities or transactions during that period can be examined.

Pre-Audit Planning

Here, the auditor needs to obtain information about the audit that will enable her to establish the audit plan. Information needed includes

• Location or locations that need to be visited

• A list of the applications to be examined

• The technologies supporting each application

• Policies, standards, and diagrams that describe the environment

This and other information will enable the IS auditor to determine the skills required to examine and evaluate processes and information systems. The IS auditor will be able to establish an audit schedule and will have a good idea of the types of evidence that are needed. The IS audit may be able to make advance requests for certain other types of evidence even before the on-site phase of the audit begins.

For an audit with a risk-based approach, the auditor has a couple of options:

• Precede the audit itself with a risk assessment, to determine which processes or controls warrant additional audit scrutiny.

• Gather information about the organization and historic events to discover risks that warrant additional audit scrutiny.

Audit Statement of Work

For an external audit, the IS auditor may need to develop a statement of work or engagement letter that describes the audit purpose, scope, duration, and costs. The auditor may require a written approval from the client before audit work can officially begin.

Establish Audit Procedures

Using information obtained regarding audit objectives and scope, the IS auditor can now develop procedures for this audit. For each objective and control to be tested, the IS auditor can specify

• A list of people to interview

• Inquiries to make during each interview

• Documentation (policies, procedures, and other documents) to request during each interview

• Audit tools to use

• Sampling rates and methodologies

• How and where evidence will be archived

• How evidence will be evaluated

Communication Plan

The IS auditor will develop a communication plan in order to keep the IS auditor’s management, as well as the auditee’s management, informed throughout the audit project. The communication plan may contain one or more of the following:

• A list of evidence requested, usually in the form of a PBC (provided by client) list, which is typically a worksheet that lists specific documents or records and the names of personnel who can provide them (or who provided them in a prior audit).

• Regular written status reports that include activities performed since the last status report, upcoming activities, and any significant findings that may require immediate attention.

• Regular status meetings where audit progress, issues, and other matters may be discussed in person or via conference call.

• Contact information for both IS auditor and auditee so that both parties can contact each other quickly if needed.

Report Preparation

The IS auditor needs to develop a plan that describes how the audit report will be prepared. This will include the format and the content of the report, as well as the manner in which findings will be established and documented.

The IS auditor will need to ensure that the audit report complies with all applicable audit standards, including ISACA IS audit standards.

If the audit report requires internal review, the IS auditor will need to identify the parties that will perform the review, and make sure that they will be available at the time when the IS auditor expects to complete the final draft of the audit report.

Wrap-up

The IS auditor needs to perform a number of tasks at the conclusion of the audit, including the following:

• Deliver the report to the auditee.

• Schedule a closing meeting so that the results of the audit can be discussed with the auditee and so that the IS auditor can collect feedback.

• For external audits, send an invoice to the auditee.

• Collect and archive all work papers. Enter their existence in a document management system so that they can be retrieved later if needed, and to ensure their destruction when they have reached the end of their retention life.

• Update PBC documents if the IS auditor anticipates that the audit will be performed again in the future.

• Collect feedback from the auditee and convey to any audit staff as needed.

Post-Audit Follow-up

After a given period (which could range from days to months), the IS auditor should contact the auditee to determine what progress the auditee has made on the remediation of any audit findings. There are several good reasons for doing this:

• It establishes a tone of concern for the auditee organization (and an interest in its success) and demonstrates that the auditee is taking the audit process seriously.

• It helps to establish a dialogue whereby the auditor can help auditee management work through any needed process or technology changes as a result of the audit.

• It helps the auditor better understand management’s commitment to the audit process and to continuous improvement.

• For an external auditor, it improves goodwill and the prospect for repeat business.

Audit Evidence

Evidence is the information collected by the auditor during the course of the audit project. The contents and reliability of the evidence obtained are used by the IS auditor to reach conclusions on the effectiveness of controls and control objectives. The IS auditor needs to understand how to evaluate various types of evidence and how (and if) it can be used to support audit findings.

The auditor will collect many kinds of evidence during an audit, including:

• Observations

• Written notes

• Correspondence

• Independent confirmations from other auditors

• Internal process and procedure documentation

• Business records

When the IS auditor examines evidence, he needs to consider several characteristics about the evidence, which will contribute to its weight and reliability. These characteristics include the following:

• Independence of the evidence provider The IS auditor needs to determine the independence of the party providing evidence. She will place more weight on evidence provided by an independent party than upon evidence provided by the party being audited. For instance, phone and banking records obtained directly from those respective organizations will be given more credence than an organization’s own records (unless original statements are also provided).

• Qualifications of the evidence provider The IS auditor needs to take into account the qualifications of the person providing evidence. This is particularly true when evidence is in the form of highly technical information, such as source code, system configuration settings, or database extracts. The quality of the evidence will rest partly upon the evidence provider’s ability to explain the source of the evidence, how it was produced, and how it is used. Similarly, the qualifications of the auditor come into play, as he will similarly need to be able to thoroughly understand the nature of the evidence and be familiar enough with the technology to be able to determine its veracity.