Chapter 6

University of Salamanca

Abstract

This chapter tells the tale of the University of Salamanca, one of Spain’s and Europe’s oldest, continuously operating universities. The university’s glory days coincided with the Spanish Golden Age (the period from the late 15th to 17th centuries). Like many other ancient universities, Salamanca had its ups and downs but navigated political and financial storms, and is today a thriving, cosmopolitan institution.

Keywords

Salamanca; Spain; Architecture; Religion; Student riots; Siglo de Oro; Los Reyes Católicos; Colonization; Examinations

The University of Salamanca is one of the oldest European universities in continuous existence, its octocentenary to be celebrated in 2018, though as with other Ancients, dates should probably be taken with a pinch of salt (Fernández, 1904, p. 6[39]–6[40]). Salamanca’s peers, in terms of longevity at least, include Bologna and Oxford—august company indeed. The city is home to thousands of students from all corners of the globe (roughly a sixth of the 30,000 strong student body hails from overseas), who for generations have flocked to its classrooms, labs, and lecture theatres. Salamanca is the epicentre of Spanish language teaching and also a major locus of Spanish philological scholarship. The university may not rank among the global super elite (it falls behind Barcelona, Madrid, and others, for instance, in the national rankings), but it is nonetheless an institution of considerable renown and one that possesses a certain social cachet. The city itself is dizzyingly polyglot, vibrantly cosmopolitan, and very much a destination of choice for young people, not least Americans, intent on spending a study year or semester abroad.

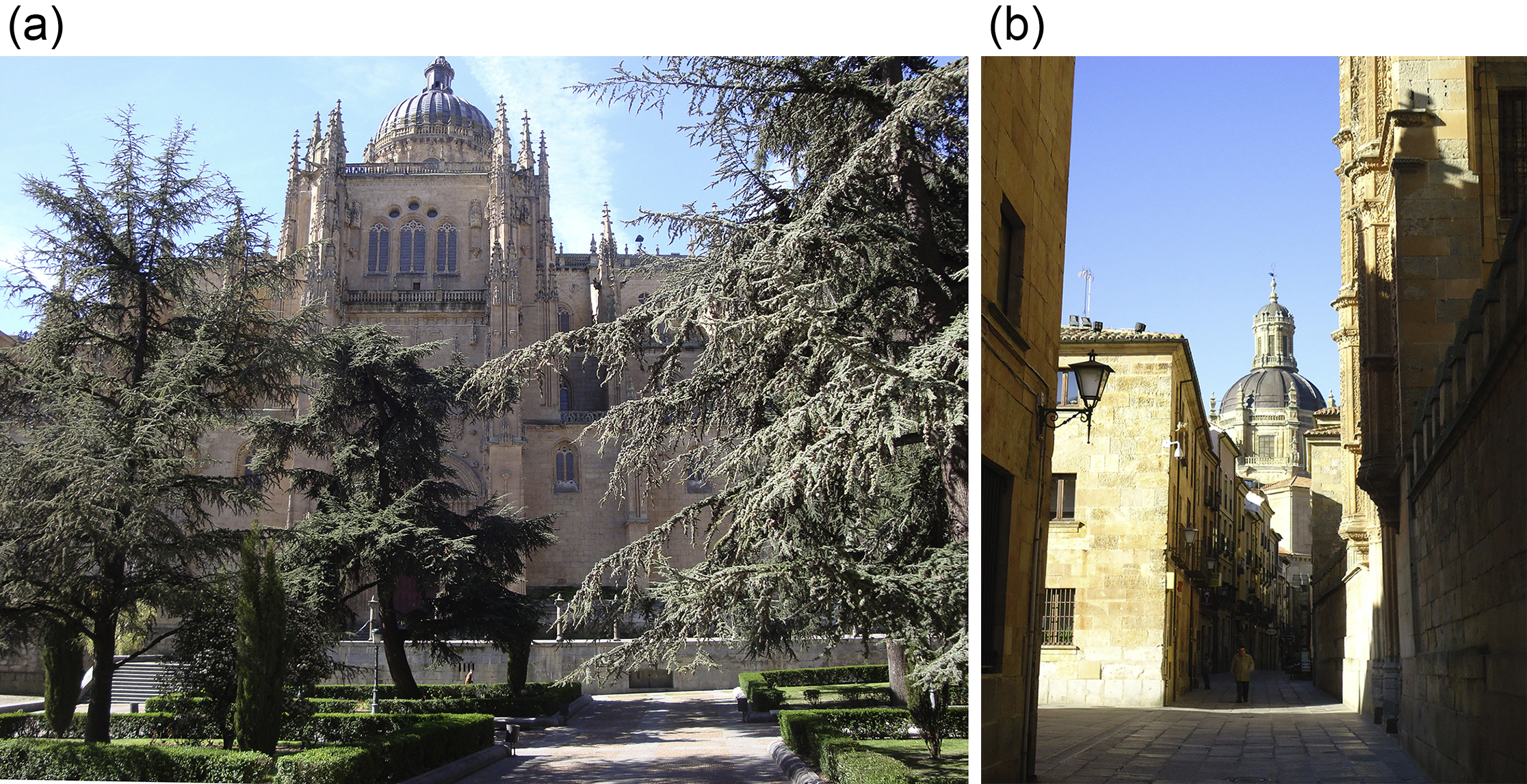

The nascent institution was granted its royal charter in 1218 by King Alfonso IX of Léon, which is to say that the status of the pre-existing Cathedral School was effectively upgraded while continuing to function as the principal site of instruction. The title ‘university’ was first formally granted to the ‘School of Salamanca’ in 1254 by King Alfonso X of Castile and Léon and confirmed in a papal bull by Pope Alexander IV a year later (Villar, 1980, p. 17). Early on, the administration rented classroom space here and there, including in the imposing Dominican convent of St Stephen, while students, as was common in the earliest universities before residential colleges or halls were established, lived in the local community, renting or sub-renting rooms, boarding with townsfolk, or even lodging with their professors (Figure 6.1a and b). At Salamanca, as at some other medieval universities, a conservator, whose role was to nurture harmonious town-grown relationships and protect the rights and privileges of members of the university community, was responsible for the regulation of rents. Alfonso X, a sage fellow, decreed that, ‘The city where the School is to be established should have good air and beautiful environs, so that the masters who teach and the students who learn may live there in health and may rest and enjoy themselves in the evening when they are weary from study’ (quoted in: Villar, 1980, p. 15). Anyone traversing Salamanca’s cacophonous Plaza Mayor, one of the world’s great public spaces, after the work day has ended will be left in no doubt that the monarch’s advice regarding eventide relaxation continues to be heeded to the fullest extent, by both town and gown.

The city of Salamanca has been around much longer than its eponymous university. It was founded by Celtic tribes, settled by the Romans, and subsequently taken by the Moors in the eighth century before its eventual re-conquest and gradual emergence as a major centre of learning and ecclesiastical power, beginning in the 12th century and reaching its apogee around the 16th century (the Siglo de Oro, or Golden Century). That is the pocket version of events; the reality is, of course, much more convoluted.

The Old City, sometimes referred to as La Dorada, or Golden City, because of the warm honey-coloured glow of its sandstone buildings, which look as if they have been fashioned out of huge slabs of fudge, is the crowning glory of the region (Figure 6.2). It, however, is not the most obvious of locations for one of the world’s most venerable universities. The city of Salamanca, population roughly 200,000, lies untroubled in the arable flatness of northwest Spain, some 120 miles from Madrid, high above sea level. It is a living city cloaked in antiquity. A reconstructed first-century Roman footbridge, stonily guarded at one end by a headless pig (also referred to, fancifully, as a lion), funnels visitors and Sunday strollers across the Tormes River to the foot of the city walls, from behind which rises the blended mass of the Old and New Cathedrals. Salamanca is a year-round tourist attraction, for Spaniards as well as foreigners. In 1988, the Old City, a kaleidoscopic commingling of Romanesque, Moorish, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque elements, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. The university is, arguably, the Koh-i-Noor in the city’s coruscating architectural crown. This is not the Castile of which Somerset Maugham wrote, ‘with its reserve, its taciturnity and its ceremonial stiffness’ (Maugham, 2000, p. 43) (Figure 6.3a and b).

There is no disputing the fact that Salamanca is an outrageously beautiful city, an architectural delight that oozes religion and religiosity. Decay, decomposition, dereliction, degeneration, and deliquescence are certainly not words that come to mind as one wanders from college to chapel, monastery to square, cathedral to museum, university to convent, library to dormitory. Yet, at the risk of sounding heretical, the town is almost too good to be true. So much of what greets the eye has been painstakingly restored, primped, and lovingly polished. Are visitors perhaps traversing a giant Warner Brothers lot transformed into a late medieval city? The relentless tide of youth suggests not.

∗∗∗

Like other ancients, the University of Salamanca has had its ups and downs; history did not always treat it leniently, as Julian Alvarez Villar (1980) makes clear in his readable biography of the institution. The university’s initial development and subsequent expansion benefitted in no small measure from both royal and ecclesiastical patronage, in the form of exemptions from tolls and generous tithing, something that did not always go down well with the local citizenry, who felt hard done by. Students were also exempted from military service, an agreeable perquisite for some. By the end of the 14th- and beginning of the 15th century, the adolescent institution had roughly 500 students, most of whom were clerics, and multiple chairs had by that time been established in subject areas such as Canon Law, Grammar and Rhetoric, Medicine, Logic and Philosophy, Theology, and Greek. Unlike today, students in medieval times wielded significant power. At both Bologna and Salamanca, for example, a student rector, elected from among the student body, headed the institution and with his advisors was responsible for administrative affairs and academic appointments—a case perhaps, from a contemporary perspective, of the lunatics running the asylum. (Students at the ancient universities of Scotland, including St Andrews, do still elect a [Lord] rector, but this is a largely honorific appointment.) In Salamanca, professors were appointed to chairs by a process known as opposition (oposición)—a medieval joust with words rather than lances between aspirants and questioners, on the outcome of which students had the right to vote (Figure 6.4). A chair brought with it great prestige, but holders were held to certain standards; they would have their wages garnished if they missed classes without good cause and could forfeit their chair if they neglected their duties for more than 6 months. In addition, it was not uncommon for the rector to drop in on a professor’s lecture to check that the requisite material was being covered and that the teacher actually taught for the whole hour and in Latin.

With so much at stake—lifelong tenure and salaried retirement in the case of a permanent chair; a 3- or 4-year term of office in the case of a lesser position—it is not surprising that such oppositions became highly contested and highly politicised events characterised by vote canvassing: ‘The often impecunious and hungry student was subject to the inducement of a little silver or a sumptuous meal’ (Maugham, 2000, p. 242). Wheeling and dealing, more or less blatant, has always been a feature of academic politicking: ‘Each of the great religious orders was anxious to have its members hold theological chairs, and the colleges had the same attitude towards the chairs of law. Thus, intense competition, coupled with the turbulent nature of the Salamancan students, caused public quarrels and denunciations or even riots in which the crown constantly had to intervene’ (Addy, 1966, p. 17). Rivalries also existed between different naciones (between students from, for instance, Andalusia and the Basque country), which could lead to the flourishing of arms and the shedding of blood. And like any self-respecting university d’un certain âge, Salamanca had its very own St Scholastica Day-like riot, in November 1644, when town and gown set upon one another with gusto: pistols, swords, and more were called into service, mayhem resulted, and old scores were settled vengefully. From the earliest times, there had existed ‘a smouldering enmity between town and gown’ (p. 49) in this fairest of cities.

Modest growth and unhurried construction of university premises characterised Salamanca in the 15th century. In 1474, the building of the first university library, a collection of 200 or so volumes, was begun; it opened for 4 hours a day (Rodríguez-San Pedro Bezares, 1991, p. 12). Teaching, at Salamanca as elsewhere, consisted of lectures, disputations, and systematic analysis of classical and sacred texts, all conducted in Latin, and that continued very much to be the case until the major curricular reforms that were exhaustively debated during the late 18th- and early 19th centuries injected the spirit of the Enlightenment into the corridors and classrooms of straitlaced Salamanca.

Steady as she goes soon gave way, though, to full steam ahead. The university’s halcyon days coincided with the Siglo de Oro, a time of artistic flowering and humanistic thought, and a newfound focus on political, legal, and economic issues. This was also a momentous period of colonisation for Spain, the morality of which was debated at Salamanca, and by none more vigorously than the noted scholar Francisco de Vitoria, who, with enthusiastic student support, had been elected in 1526 to the Prima Chair in Theology, the most sought-after professorship in all of Spain at the time. During his years at the university, Vitoria taught thousands of students, and his trenchant views on the inalienable rights of indigenous peoples earned him widespread fame and enduring respect. For some, he is nothing less than the father of what today is called international law, and in turn the classroom in which he taught in the Escuelas Mayores is no mere classroom, rather ‘it is the cradle of international law’ (Scott, 2000, p. 75). Such, in fact, was the university’s standing at the time that Christopher Columbus travelled to Salamanca to discuss with members of a specially convened royal commission his credulity-stretching plans for reaching the East Indies by sailing westwards across the Atlantic: they ‘scoffed at [his] idea that the world was round’ (Mertz, 1998, p. 609). Salamanca was also home for a few years to Hernán Cortés, who conquered the Aztec empire. Cortés entered the university at age 14 but left before graduating to join the ranks of ‘those brutal, courageous, passionate, idealistic, earthy, humorous, cruel and humane men who subjected a continent and discovered a world’ (Maugham, 2000, p. 56).

Gold from the Americas fuelled the growth of higher education throughout Spain, while the country’s territorial aggrandisement in turn created a demand for a new breed of professional civil servant, known as letrados. It was thus that the Catholic Monarchs (los Reyes Católicos), Ferdinand and Isabella (Figure 6.5), looked to leading universities like Salamanca to train future generations of state officials and career bureaucrats—the aforementioned letrados—knowledgeable in jurisprudence and public administration.1 These truly were the institution’s glory days, architecturally and academically: ‘The Spanish universities are at the height of their glory, and Salamanca is queen among them all. The seventy chairs of the university are filled by the best scholars of the age and provide instruction not only in the usual subjects of a curriculum inherited from the Middle Ages … but also in more out-of-the-way branches of knowledge …’ (Grice-Hutchinson, 1952, p. xi). Medicine, however, was still finding its feet, with far fewer matriculated students than other faculties: in the last quarter of the 16th century, Medicine had on average 180 students compared with Canon Law’s almost 2,800. In fact, the history of medicine at Salamanca was checkered—now flourishing, now faltering. Much has changed since the creation in the mid-16th century of the House of Anatomy (destroyed by flooding) with its anatomical amphitheatre, where the cadavers of paupers and executed people were dissected. Its most recent successor, the anatomical amphitheatre attached to the Colegio Mayor del Arzobispo Fonseca, was built in 1925 but is now used for other purposes, the Faculty of Medicine having decamped to much more modern and spacious quarters outside the city.

By the second half of the 16th century, the university was home to roughly 6,500 students, high and low born, wealthy and impecunious, diligent and indolent. Upper-crust students, as at other ancient universities over the centuries, behaved in the manner to which they were accustomed, while being indulged by the university authorities who typically granted them a long leash: ‘Noble youth were often accompanied to class by their retinue and sometimes sent only their servants to take notes for them’ (Anderson, 2002, p. 240). Similar practices are not unheard of today, of course, though they are no longer the prerogative of the socially elite.

As with empires, so it is with institutions. The effulgence of the Golden Century ceded to stagnation, and by the 18th century Salamanca had lost much of her lustre: ‘A stale and vapid curriculum, too often taught by a lackadaisical and routinarian faculty … a faulty system of tenure’ and students who ‘were lazy and absent from class’ (Addy, 1966, p. xv). Desuetude wasn’t all: the university was operating under straitened financial circumstances, and belt tightening was the order of the day; in 1752 a royal decree required that the institution curtail its spending on the pomp and ceremony associated with the awarding of doctoral and master’s degrees. Sumptuary laws in the groves of academe, no less! But worse was to follow. Military conflict, economic crises, and epidemics took their predictable toll. The Spanish War of Independence, as wars have often done to Europe’s great and ancient universities, caused major disruption and considerable damage to university property, with the result that the number of matriculated students plummeted to less than 200 in the early 1800s. The bloody Battle of Salamanca in July 1812, at which the Duke of Wellington’s forces routed the French, was a particularly dark day for both city and university.

A gradual but important recovery began in the late 19th century under the leadership of the philosopher and writer, Miguel de Unamuno, whose head is one of many notables to be seen on the medallions dotted around the great Plaza Mayor (Figure 6.6). He was appointed rector twice, first from 1900 to 1924 and later from 1930 to 1936. The owlish Unamuno, with his long nose and peering, bespectacled gaze, was a man of exceptional moral courage and integrity, who was exiled in 1924 for his outspoken criticism of the government of General Miguel Primo de Rivera. His subsequent denunciation in 1936 of General Francisco Franco’s newly installed regime almost got him shot and resulted in his house arrest, during which he died of a heart attack. Unamuno was instrumental in, to take just one specific illustration, creating and securing government funding for the new Faculty of Medicine and, more generally, in putting Salamanca firmly back on the academic map. The former Rector’s residence is now a museum (La Casa-Museo Unamuno), which sits immediately next to the main entrance to the Escuelas Mayores, the historic core of the university. The two-story 18th-century building, the impressive doorway of which is flanked by pilasters on tall plinths and crowned with an ornately carved university coat of arms, incorporates a reception area, an archive, and a small research centre. On the upper floor, visitors can see Unamuno’s simple brass-framed bed and crucifix, paintings (several of the man himself) and antique furniture, a simple study with his desk and personal effects, and his library and academic gown—all frozen in time. The much-loved Unamuno reinvigorated the moribund institution, and such has been its growth ever since that the Old City can no longer contain the university within its clutches.

∗∗∗

The core of the University of Salamanca consists of three interconnected components: the Patio de Escuelas (the Courtyard of the Schools), the Escuelas Mayores (the Upper, Major, or Senior Schools building—all three qualifiers are used in translation), and the Escuelas Menores (the Lower, Minor, or Junior Schools) (Figure 6.7a, b and c). These ancient buildings are tightly contained in the Old City, although they may be easily missed by the map-clenching, first-time visitor as they are dwarfed on the one hand by the tied-at-the-hip Old (12th century) and New (16th century) Cathedrals and on the other by the skyscraping towers of the Pontifical University, established to fill the pedagogic void when the Spanish government dissolved the faculties of theology and canon law at the ancient university in the 19th century.

The Patio de Escuelas is the historical axis of the university—with the Escuelas Mayores and Escuelas Menores (where young students were prepared for admission to the university proper) connected via the courtyard, the most important component of which is the former Hospital del Estudio. Built in the 15th century, the hospital no longer functions as a safe haven for ailing or needy students as its name might suggest. Today it houses the rectorate and a tastefully renovated boardroom (Sala de Juntas), formerly a chapel, where the university’s governing body convenes. A statue of the tonsured Fray Luis Ponce de León, who was appointed Thomas Aquinas Professor of Theology in 1561 and is a revered figure in the history of the university, commands the Courtyard of the Schools, wryly amused, one imagines, by the clumps of peering and pointing tourists below, their telephoto lenses seeking out one grotesque element in particular: the little frog (in medieval iconography a symbol of lust) that sits atop a skull high up on the right-hand side of the façade (Figure 6.8). According to local lore, those who espy the frog will succeed academically, though another version has it that one will be married within a year if he or she spots it. Truth be told, there are almost as many frog stories as there are motifs on the façade.

If you want to know what a university looked like in the 16th century, what it would have felt like to be a doctor expatiating ex cathedra, a student sitting shivering in a chilly classroom, or a scholar poring over incunabula in a closed-access library, the relatively compact Escuelas Mayores is as good a place as any in Europe to visit. Construction of the Escuelas Mayores began in 1415, yet the upper floor was not completed until 1879. The building’s stunning Plateresque façade was completed in the 1520s during the reign of Los Reyes Católicos, and both Ferdinand and Isabella, regally attired and clasping a single scepter (symbolising national unity), can be seen clearly above the twin doors on the first register, serenely surveying the passing generations. Plateresque (from the Spanish plata for silver) is an architectural style characterised by decorative exuberance: think twisted pillars and floral motifs, animals and skulls, fantasy creatures and festoons, shields and escutcheons. The term ‘Churrigueresque,’ after the Churriguera family of architects and sculptors, whose baroque handiwork is much in evidence in Salamanca, is also used to describe this particular genre. A little, it must be said, goes a long way, and these mantillas of masonry can sometimes result in aesthetic indigestion. The façade of the Escuelas Mayores is among the most photographed buildings not only in Salamanca, but also in Spain. It is situated at one end of the rectangular Patio de Escuelas, at the other end of which is the twin-arched entrance to the quadrangular calm of the Escuelas Menores, surely one of the most beautifully proportioned spaces in all of Salamanca. Amongst other things, it houses the University Museum, a darkened room of which contains Fernando Gallego’s 15th-century ceiling mural, The Sky of Salamanca, a faded fusion of astrological and astronomical elements.

There is much to see at the Escuelas Mayores: a running frieze rich with swirling motifs; a highly decorative honeycombed ceiling in the Moorish tradition; a three-flight stone staircase (the Stairs of Knowledge) that leads to the upper floor, encased regrettably if necessarily, as is the lower, with glass to keep the elements at bay. Everywhere ornamentation; the eye is granted no respite. This, no doubt, is what Villar (1980), in his book on the art and ceremonies of the University of Salamanca, had in mind when he spoke of ‘the traditional Spanish horror vacui’ (p. 42). What makes the setting distinctive, however, is the sequence of lecture halls and formal meeting rooms that served (and in some cases still do) the academic and administrative needs of the institution. The white-walled, small windowed lecture hall named in honour of León, with its rows of roughly hewn, backless wooden benches and scuffed desk tops, reminds one just how primitive conditions were in bygone times, though the benches were undoubtedly an improvement on straw-strewn floors, which had once been the norm here, as elsewhere. At the front of the spacious aula, there is an elevated wooden pulpit, over the back of which is ‘a wooden hood somewhat like a great extinguisher’ (Maugham, 2000 p. 160) from which tumbled words of wisdom in Latin: to hold a chair was to talk down, literally speaking, to one’s students. To the right is a balustrade with a continuous settle where members of the resident faculty and visiting luminaries would sit and listen. Little has changed, with the exception of the ectoplasmic projection of the good friar onto the podium—a disconcerting nod in the direction of the Epcot Center. The academically brilliant León taught with distinction at the university, of which he was a graduate, from 1561 until his death in 1591, except for the period 1572–76 when the Inquisition imprisoned him in Valladolid. The great man had more than one run-in with the thought police over his allegedly heretical views, in actuality all part of a longstanding feud between the Augustinians (León’s lot) and the Dominicans (his denouncers). Returning to the classroom after his involuntary absence, León ascended the pulpit and, so it is handed down, prefaced his homecoming lecture with the words, ‘As we were saying yesterday …’

Elsewhere the actors are flesh and blood, and the performance one with which León himself would have been quite familiar. The Assembly (or Ceremonies) Hall, formerly the lecture theatre for canon law, is now reserved for events of the kind that Salamanca organises so well. The vaulting is not unlike that of a giant cave in a Rioja winery, the overall effect not unlike that of a chapel. But there are no oak casks, no polychrome saints here. Instead there are rows of red-upholstered seats, a dais, six chairs, and a presidential table bedecked, incongruously, with a free-standing crucifix facing the assembled dignitaries, behind all of which rises a giant triangular canopy crowned by the pontifical coat of arms. On the walls hang 17th-century Brussels tapestries (another giant exemplar can be found in the Sala de Juntas) and a 19th-century grisaille of the ubiquitous Ferdinand and Isabella. To either side, empty seats await the colourfully attired members of the faculty, who will walk two-by-two in their finery from the Aula Francisco de Salinas through the ancient building to the Assembly Hall (the ceremonial robes are stored in glass cupboards for all to see), where the honorary doctorate recipient will take centre stage. A staff-carrying master of ceremonies, flanked by a pair of heralds wearing red velvet tabards and leggings, leads the procession. The pastel-coloured capes (the different colours signify the different faculties), which are worn over black gowns with cuffs made of white lace, are topped off by matching multitasseled birettas—all in all a most distinctive ensemble. Spanish academic dress is very different from that of, for instance, Oxford where the preference is for wing-sleeved gowns and black mortarboards or Finland where a silken top hat and sword are awarded to doctoral students. Factor in the music, and the overall impression is more high church than highbrow, but no less impressive for that.

Lucky is the scholar who is invited to Salamanca to receive an honorary degree, for this is an institution that respects tradition and knows how to put on a show. Your accomplishments will be extolled by your sponsor, after which the Rector Magnifico, speaking in Latin, will place an appropriately coloured biretta, its tassels a-shimmering, on your head, present you with a gold medal and, for good measure, slip a ring on your finger to symbolise your future attachment to the university. Before the proceedings conclude and the dignitaries recess (in reverse order, the oldest faculties to the fore) you will be bear-hugged successively by the rector and the bow-tied Doctors, and, from a pulpit off to the side, you will then deliver an acceptance speech that will be followed, in turn, by an address from the rector. This will be a day, a spectacle not easily forgotten.

There is still much more to see in the Escuelas Mayores, including an ornately decorated chapel; facsimiles of important historical documents pertaining to the formative university; a restored 16th century, penis-challenged manikin used for bandaging practice; religious statuary and relics; yet more paintings of Spanish monarchs; and at one corner of the upper gallery the spectral remains of a severely faded mural featuring two figures holding, it would seem, staffs and lit candles. Their intended purpose was not so much to elevate the spirit as to deter incontinent or lazy students in the nearby lecture halls from using this corner as an ersatz urinal when the call of nature was too strong to ignore.

The pièce de résistance of the Escuelas Mayores is the Old Library, off limits to the casual visitor. One must peer through the nose-smudged glass entrance to glimpse the Baroque wooden bookcases, their finely bound contents now at near permanent repose. A distinctive feature of the large rectangular reading room, with its vaulted ceilings, is a much photographed collection of (to use the language of the original cataloguers) ‘round books,’ or globes from different parts of Europe that were donated to the university in the middle of the 18th century. Look but don’t touch is the message in this library. (In earlier days, the Vatican threatened book thieves with excommunication.) Margarita Becedas’s (2002) book, one of a series of pocket-sized publications, Historia de la Universidad, produced by the university press, describes some of the treasures (Bibles, maps, missals, manuscripts, codices, incunabula, engravings, etc.) housed in the ancient university library, where one will also find the arca boba (fool’s chest), a heavy-duty, high-security safe for storing the university’s valuables, not unlike Sir Thomas Bodley’s ‘blacke iron Chest’ at the University of Oxford.

Not part of the university, but an important part of the institution’s long history is the Old Cathedral, much of which was destroyed as a result of the great Lisbon earthquake of 1755. For years, students completing their licentiate degree would defend their thesis and debate the finer points of law, philosophy, or theology with their professors—‘the dreaded nocturnal examination’ (Addy, 1966) as it was known—in the small, decorative jumble that is the Chapel of St Barbara, one of several dotted around the cathedral cloister. Popular accounts have the nerve-wracked student spending the night seated in a leather chair (it is still there and can be sat upon with admission fee to the Old Cathedral) at the foot of the altar, his feet touching the tip of the tomb of Bishop Juan Lucero (who founded the chapel in 1344). Behind the student on the retable can be seen a graphic depiction of the decapitation of St Barbara. Now, if that didn’t help focus the candidate’s mind … (Figure 6.9). George Addy’s (1966) detailed account of the rituals and procedures involved in a doctoral defence suggests that the candidate went home after the initial encounter and only returned to the chapel the next day accompanied en route by junior faculty members in full academic regalia. As the examination protocols were protracted, a dinner was required. The cost of the repast was borne by the student, who was additionally obligated to provide each examiner with ‘two doblas or castellanos, one large wax candle, a box of citron, a pound of sweets, and six hens,’ while also ensuring that the ‘bedels received four chickens, and the constable and secretary received three reals each plus their supper’ (Addy, 1966, p. 31). To each his just desserts, it would appear. Today, this would be viewed as tantamount to bribery or at the very least evidence of a conflict of interest.

Graduation was thus not merely an ordeal but also a cripplingly expensive business—prototypical student debt, if you will—for doctoral students, as they were required to personally underwrite the cost of processions, musicians, banquets, and the dispensing of far from trifling gifts. The multiday ceremonies typically concluded with a bullfight in the main square of Salamanca after which the student would write his vítor (or victor) on the walls of the university using the blood of the bull mixed with (the recipe varies ever so slightly) clay, oil, and paprika. The term vítor is an anagram with each letter personalised. This form of tagging dates from the 14th century and is associated most especially with Salamanca (Figure 6.10a and b). The walls of the principal university buildings and of the major colleges throughout the city are covered with these deep red inscriptions that celebrate successful doctoral defences, a charming tradition that persists. It all makes today’s doctoral hooding ceremony at American universities seem anemic in comparison.

On exiting the cathedral, the successful student would be greeted by minstrels known as tunos, who sang and serenaded newly minted doctors and, in good troubadour tradition, young lovelies. This was how tunos strove to make ends meet. The tradition flourishes, and it is commonplace today to see troupes of young (almost always male) musicians (students or recent graduates) dressed in minstrel costumes, a coloured sash across their torso indicating the faculty to which they belong, playing a mix of instruments: guitar, bandurria (similar to a lute), accordion, tambourine, and drum. The Plaza Mayor, with its captive throng, is one place where they can be relied upon to ply their trade with relish.

Needless to say, there is an admission charge to tour the Escuelas Mayores. Salamanca knows full well the commercial value of its well-preserved historical assets and misses not a trick in packaging its patrimony. Multilingual tour guides and serpentine school parties, more interested in their iPhones than the finer points of Spanish Plateresque, will go where’er you go (Figure 6.11). And—no accident this—tourists exit the university precincts through a remarkably well-stocked shop selling a wide selection of university-related apparel and university-branded ware, with some items priced in the 600–700 Euro range. What would the late Unamuno make of it? But, to be fair, that is no different (bar the eyebrow-raising price tags) from Christ Church in Oxford, King’s College Chapel in Cambridge, or the Library of Trinity College Dublin. Academe is now an established sub-genre of cultural tourism, with all of the associated paraphernalia and merchandising gimmicks. Audio guides and QR codes are provided for those who don’t trust their own eyes or simply want to switch off.

∗∗∗

No history or profile of the University of Salamanca would be complete without some mention of the constellation of colleges (major and minor, in local terminology) that, between the 14th and 17th centuries, grew up around the university. In certain respects, the collegiate system of Salamanca was akin to the early network of Oxbridge halls, essentially a mechanism for providing students with a home, security, and financial support, albeit in this case one based on a rather complicated set of institutional arrangements. Although the various colleges operated under the university’s ‘influence and protection … acknowledging the authority of the Rector or Chancellor’ (Villar, 1980, p. 90), the system fell into decline and eventual dissolution as a result of constitutional abuses, structural tensions, and internal squabbles.

Two of the most distinguished and architecturally significant of the major colleges are today fully functioning parts of the university. The older of these (founded in 1401) is the Colegio Mayor de San Bartolomé (also known as the Colegio de Anaya), housed in a particularly fine Neoclassical structure (not its original home) on one side of the airy Plaza de Anaya directly opposite the New Cathedral (Figure 6.12). At the building’s heart there is a dignified quadrangle, from which a monumental staircase leads to the upper level. Countless busts, portraits, and medallions populate this lovingly restored space. Within the interior of the college are generations of red victors and celebratory initials proudly adorning the walls; here, past and present commingle effortlessly. The same holds for the Colegio Mayor del Arzobispo Fonseca, popularly known as the Royal College of Irish Nobles, as it was here during the 16th century that Irish Catholics came to escape political and religious persecution in their homeland and train for the priesthood. Over the years many who went on to become eminent leaders of the Church in Ireland were prepared in Salamanca. Until the middle of the 20th century, the college maintained its Irish connections and special character. Today, however, Colegio Arzobispo Fonseca is a university residence, with its own bar and chapel (boasting a resplendent gilded altarpiece), for visiting scholars and distinguished visitors, and it is a tourist attraction in its own right: the building was declared a national monument in 1931. The square courtyard, a most harmonious arrangement, has galleries on two levels, access to which is provided by a pair of Renaissance-style cloister stairways (Figure 6.13a and b). Visitors directing their gazes upwards will see decorative pinnacles, continuations of the gallery’s columns, atop each one of which is perched a naked child, something for sash-wearing graduates and their happy families to giggle about while sipping cava and nibbling canapés at commencement receptions.

Complementing the historical core of the university is the purpose-built, strategically conceived Villamayor campus (Campus Universitario Miguel de Unamuno, to give it its full name), a brisk 20-minute walk from the narrow streets and animated squares of the city centre. Most of the academic schools, departments, and university-linked research centres are now concentrated on this sprawling green-field site close to the banks of the river; Philology, housed in the Colegio Mayor de San Bartolomé, and Chemistry, housed in a stolidly modern building just inside the city walls overlooking the Roman bridge, are two exceptions. Yet few, if any, tourists will venture beyond the remnants of the city walls to visit Villamayor, a campus that only came into being within the last decade or two. Most will have no idea that it even exists and will depart believing that the university is synonymous with, and reducible to, a half a dozen or so exceptionally pretty structures. The main university library, named after Francisco de Vitoria and containing almost 1 million volumes, is located on the Villamayor campus, far removed geographically, architecturally, and functionally from its predecessor (Figure 6.14). The library is an uncompromising modernist construction, encased in girders of yellow steel; it could be easily mistaken for an airport terminal.

Salamanca, while carefully curating its heritage and public image, is not afraid to break with tradition. Most of the university departments (Medicine, Biology, Law, Philosophy, Pharmacy, etc.) and university-related research centres—by far the most striking of which is the red-clad, Neo-Brutalist home of the IBFG (Instituto de Biología Funcional y Genómica)—that make up the Villamayor campus are constructed of locally hewn stone and brick and generously spaced, in anticipation of further growth (Figure 6.15). The soul of the university may lie in the Old City, but the master-planned heart of the enterprise is to be found in Villamayor.

∗∗∗

Very rarely is the name of a female encountered in the recorded history of the university. In that regard, Salamanca is no different from most of its institutional peers throughout Europe. Beatriz Galindo, born sometime between 1464 and 1474 in Salamanca, was an exception. A prodigy, she studied grammar and Latin at one of the University of Salamanca’s dependent institutions, and her academic prowess soon brought her to the attention of the local professorate. ‘La Latina,’ as she was to become known far and wide, graduated in Latin and Philosophy at the University of Salerno before returning to her native Salamanca, where she was appointed preceptor to the children of Queen Isabella (of whom she also became a confidante) and may have taught at Salamanca, though the records are murky on this. Galindo subsequently moved to Madrid, where she established a hospital. Statues of La Latina can be found in both cities. Another trailblazer and near coeval peer was Lucía de Medrano, who may also have taught classics for a period at the university at the beginning of the 16th century, but as with Galindo, there is a dearth of conclusive documentary evidence.

∗∗∗

Despite all the changes, challenges and tribulations the centuries have brought, the University of Salamanca forges ahead, rightfully protective of its traditions, proud of its longstanding connections to, and influence on, universities in Latin America, and acutely aware of the need to adapt continuously to shifting societal demands and expectations. In all of this, ‘lo único esencial, lo único vertebral y permanente sea la continuidad en la referencia simbólica, la fascinacion de un nombre: ¡Salamanca!’ (Rodríguez-San Pedro Bezares, 1991, p. 21).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.