Chapter 7

Leiden University

Abstract

This chapter recounts the history of Leiden University, which is very closely linked to the history of the charming city that bears that name. Established in the 16th century, Leiden University is Holland’s premier institution of higher education, with historical strengths in several fields, including law, physics, and medicine. The university’s famed Botanical Gardens are popular with tourists.

Keywords

Leiden; the Netherlands; Town and gown; William of Orange; Hortus Botanicus; Architecture; Canals; Nobel Prize

Holland’s oldest and most prestigious university, Leiden University has a most impressive roster of alumni (presidents, prime ministers, royalty, Nobel laureates) and has justifiably earned its place in the pantheon of Western Europe’s institutions of higher education. What made Leiden (sometimes Leyden)—a sleepy, modestly sized, and incorrigibly picturesque city of interlocking canals, narrow streets, and centuries-old, lopsided dwellings, home once upon a time to textile manufacturing and book production and today to whooshing bicycles, clanking church bells, and chugging boats—a candidate for the site of the Republic of the United Provinces’ (as the nascent Netherlands were known) first university more than 450 years ago (Figure 7.1a and b)? The widely recounted, though possibly apocryphal (Jurriaanse, 1965), version of events is that William the Silent, Prince of Orange and leader of the revolt against Spanish dominion in the Eighty Years’ War, chose to reward the city of Leiden and its citizens for the resistance they offered to Philip II’s forces during the harrowing siege of 1574. The grateful monarch offered his doughty but battered subjects a choice: a university for their city or tax exemption; the citizenry in its collective wisdom selflessly took the long view. In hindsight, they chose wisely (assuming they actually did make such a choice) and are to be congratulated. Today, this alluring city of 120,000 inhabitants plays host to thousands of young minds from Holland and all corners of the globe who come because of the university’s outstanding academic reputation, reflected in both European and world rankings. With 20,000 students swarming around, Leiden is, statistically speaking, a university town, yet perhaps not as obviously so as some American college towns, such as Chapel Hill, North Carolina or Oxford, Mississippi, or, for that matter, St Andrews in Scotland. Students from the United States in particular may be drawn by the fact that Leiden was for several years a not unwelcoming home to the Pilgrims, who operated a printing press in the city in the early 17th century in an effort to spread their gospel before finally setting sail on the Mayflower for the New World. It was also home to a young John Quincy Adams, sixth president of the United States, who studied for a brief period at the university.

In establishing the university, there would be no papal bulls, no ties to Rome, just as would be the case a few years later in Dublin with the founding of Trinity College. This was to be a Protestant university, accommodating and reflecting the views of not only strict Calvinists but also those of latitudinarian disposition: ‘moderates and precisians’ (Woltjer, 1975, p. 1). The university’s contemporary blue-and-white seal still carries the institution’s name (taken from a nearby Roman fort) in Latin, Academia Lugduno Batava, along with its motto Praesidium Libertatis, which translates to ‘Bastion of Liberty.’ Forbearance and freedom of conscience were the ideals championed by the founding fathers, and over the years the university has strived to create and maintain a democratic and intellectually inviting ethos.

Willem Otterspeer (2008) has written an affectionate, richly illustrated history of the university, which takes the reader effortlessly from the earliest times to the present. Spoils from a number of confiscated Catholic monasteries bankrolled the royally decreed university. Ironically, but inconsequentially, the university’s charter, dated January 6, 1575, was issued in the name of rebuffed King Philip II of Spain, who was still de jure count of Holland. The following month, the establishment of the university was celebrated with prayer and perorations in a thronged Pieterskerk, the church in Leiden dedicated to St Peter, and resting place of some of the most notable figures in the history of the university (Figure 7.2). The formalities continued with a colourful procession to the new university’s first home, the former convent of St Barbara. The parade was led by a squad of soldiers in the city’s signature colours of red and white, which are today everywhere to be seen, including on the city’s coat of arms: two red keys to the gates of heaven in saltire on a white background. The procession included allegorical representations of the four faculties that would anchor teaching and scholarship in the embryonic institution: Theology, Law, Medicine, and the Liberal Arts or Philosophy. A boat, with Apollo, Neptune, and the nine muses on board, sailed along the canal, adding to both symbolism and spectacle. The celebration concluded with a modest dinner and an enthusiastic fireworks display. A depiction of the inaugural pageant and the order of procession (with names of all the dignitaries) can be seen in the Academiegebouw and also in the stylish Faculty Club immediately opposite.

The historical seal of the university, which dates from 1576, boasts Minerva as the institution’s guiding spirit. In her role as goddess of arms she reminds us of the siege and the events that led up to the creation of the university, while as goddess of wisdom she symbolizes the university’s raison d’être. In this rendition, she has laid down her arms and is seen reading a book. Minerva must have smiled favourably on her charge for in 1765 the Encyclopedia of Diderot and d’Alembert referred to Leiden University as ‘la première de l’Europe,’ even though it was relatively small. The university moved in 1577 from its initial location to the Faliede Bagijnkerk and thence in 1581 to the convent of the Dominicans of Maria Magdalena (or White Nuns) on the far side of the canal, a site which it still occupies, although the original building was destroyed by fire in 1616. It is from here on February 9 (dies natalis, as it’s known) every year that the Rector Magnificus and the black-gowned and black-bonneted professorate process to the Pieterskerk, at their head the university beadle (or pedel, to use the locally preferred variant) carrying a silver mace topped off with a statuette of—it need hardly be said—Minerva. (Leiden, it should be noted, has no monopoly of the hard-working goddess; she is a ubiquitous presence on academic domes, seals, and crests and in university plazas and courtyards around the world.) The monochrome academic garb, only very occasionally relieved by a splurge of red or green, is more sober than one would find in, say, Oxford or Salamanca, but is in keeping with the temper and history of the institution. The cool, minimally decorated, and luminous interior of the waiting church provides a further reminder of the university’s roots in the Reformation period.

Several members of the royal family have graduated from the university, including the present monarch King Willem-Alexander, as well as his mother and grandmother, Queens Juliana and Beatrix. In 2005, Queen Juliana was awarded an honorary doctorate for her commitment to freedom of expression and the responsibilities that go hand in hand with that freedom. Eighty years earlier, Queen Wilhelmina received an honorary Doctor of Law degree at the Pieterskerk on the occasion of the university’s 350th anniversary. A commemorative plaque with a relief of the queen’s head is mounted above the interior door of the Great Auditorium. The ties that bind, bind tightly in the case of the House of Orange and Academia Lugduno-Batava.

∗∗∗

The university converted the property of the former church Faliede Bagijnkerk for various uses, including the library, anatomy theatre (Theatrum Anatomicum), botanical gardens (Hortus Botanicus), and the fencing school where students were trained in swordsmanship, riding and shooting: mens sana in corpore sano. A popular series of engravings from 1610 by Willem van Swanenburg, based on drawings by the Leiden artist Jan Cornelis van’t Woudt, captured these quite different dimensions of life, each of which has a rich history, at the university in its formative days.

The seed of the university library was the eight-volume polyglot Biblia Regia, donated by William the Silent on the occasion of the institution’s founding. The first recorded mention of a library is 1587 when the Vaulted Room of the original university building was used to house the budding collection. Lack of space soon saw the library relocate across the canal to the first floor of Faliede Bagijnkerk, as depicted in the famous print by van Swanenburg. The folio volumes can be seen chained to the plutei (furniture designed for storage and reading), neatly arranged according to subject matter (mathematics, philosophy, literature, theology, etc.). In the early days, access and rights issues often came to the fore. Keys were distributed to professors and others of standing, on the condition that they would not be transferred or copied. Predictably, they were, which resulted in locks being changed and students being denied access for years on end. (For a history of the library’s first 100 years, see Pol, 1975.) With time more liberal policies evolved, and the collection, by the early 19th century housed in a greatly expanded library on the same site, grew impressively, both in size and in terms of its special holdings. That growth continued to the point that a brand new building was constructed in 1984, which once again meant hauling all the holdings across the canal. Leiden has been something of a trendsetter in modern librarianship and is credited with having produced the first printed catalogue prepared by an institution of its holdings and with being the first to systematically develop and manage special collections. In its current location, the main library of Leiden University houses more than 5 million volumes, tens of thousands of Oriental and Western manuscripts, and an extensive collections of maps. In addition, it boasts a remarkable collection of 12,000 drawings, 100,000 prints, and 80,000 photographs. Alongside paintings and prints by hometown luminary Rembrandt and many other leading Dutch painters, there are works by Canaletto, Dürer, and Hogarth.

Also since relocated from the Faliede Bagijnkerk is Leiden University’s anatomical theatre, which was built in 1596 and was one of the very first of its kind in Europe (Figure 7.3). The original structure, with six tiers of concentric seats around a rotatable dissection slab, allowed students and other interested individuals, not least members of the university senate and the city fathers, to view clearly the dissection of both animal and human bodies. Often the bodies were those of criminals who had been hanged publicly, though at other times cadavers had to be sourced from neighbouring townships by the anatomical assistant, who also worked part-time in the botanical gardens. Seating position in the amphitheatre reflected social rank, and those with most standing in the local community sat closest to the anatomical action. Such was the popularity of public dissections that they have been described as ‘a 17th century tourist attraction of the first order’ (Huisman, 2008, p. 10). A number of artists, including Rembrandt, who was born in Leiden and briefly attended its university, painted anatomical scenes, though his much analysed masterpiece, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, depicts an event that actually took place in Amsterdam, not in his birthplace. Posters would announce forthcoming dissections, which, for understandable reasons, tended to take place in the cooler months, with classes being cancelled so students could attend. Sometimes medical students were allowed to dissect an arm or a leg (Mulder, 1984, p.4). A modest admission charge was levied to deter the frivolous and those of ghoulish bent.

During the 18th century, the theatre gradually fell into disuse, before being demolished in 1821. A reconstruction of the amphitheatre greets the visitor to the Boerhaave Museum, about a 10-minute walk from Rapenburg 70, as Faliede Bagijnkerk is now known. The museum, which grew out of an exhibition of scientific and medical instruments that was mounted at the university in 1907, is named after Herman Boerhaave, Professor of both Medicine and Botany, who, in the first half of the 18th century, revolutionised the practice of medicine through his innovative bedside manner and individual treatment of patients. His name was widely known, and among those who came to Leiden to visit or study with him were Carl Linnaeus, Peter the Great, and Voltaire. In the summer months, Boerhaave would teach botany to students in the Hortus Botanicus. This Galen of the Gardens was a legendary instructor, greatly liked and hugely admired. During his time at Leiden he trained almost 2,000 students, many of whom came from abroad. Boerhaave, whose remains lie in the Pieterskerk, would unquestionably recognise the modern-day amphitheatre as being a faithful replica of the original, right down to the materials used and the dozen or so animal and human skeletons mounted on the upper echelons. These figures, which hold aloft flags with the words ‘Memento mori,’ ‘Vita brevis’ and ‘Nosce te ipsum,’ are there as reminders of the vanity of the here and now. The sleek, large-screen monitor that sits beneath the wooden panel bearing the inscription ‘Theatrum Anatomicum’ is a jarring concession to modernity. On Museum Nights, local thespians don period costume and white-coated anatomists dissect a deer.

∗∗∗

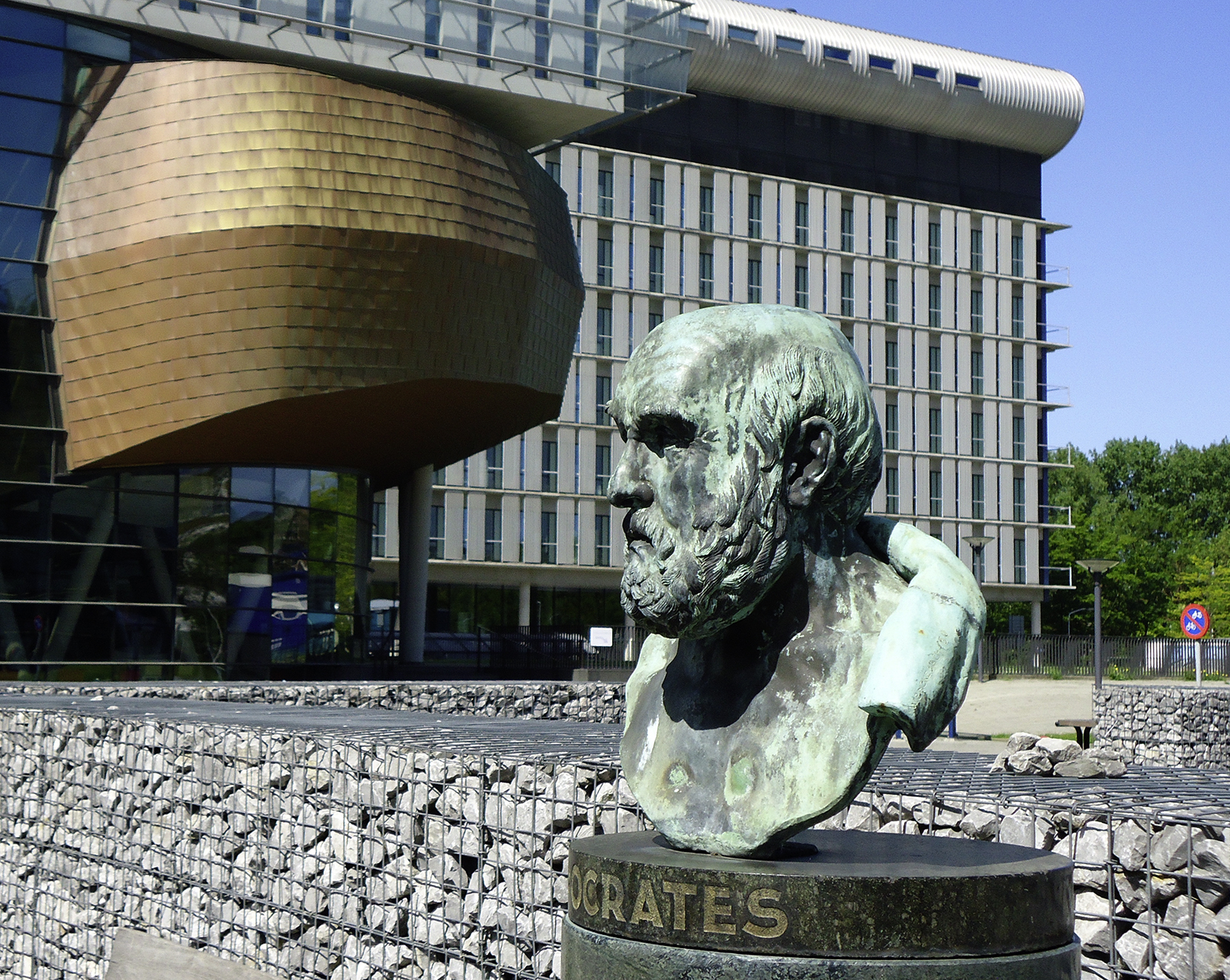

Universities, by their very nature, are dense concentrations of disciplinary expertise and repositories of codified knowledge, even though not all have equal standing in every field at any one or all times, and even though only a handful eventually emerge as uncontested centres of excellence in a particular domain. At some point in its evolution a university may become reflexively associated with a particular discipline or intellectual movement; Göttingen with mathematics and Chicago with sociology in the early part of the 20th century are two good examples of this. The sociologist Tom Gieryn (2006) refers to these (and other blue riband sites of knowledge production, validation, and dissemination) as ‘truth-spots.’ Such a place ‘lends credibility to claims and legitimacy to beliefs’ and over time becomes ‘the absolute center of gravity in a scientific field’ (p. 2). Leiden is an exemplar. In the early part of the 18th century, the university was ‘the epicenter of the network of scientists who specialised in botany and medicine’ (p. 5). Hardly surprising, then, that Linnaeus should come to Leiden from his native Sweden in an effort to have his ideas for a new taxonomic system subjected to scrutiny by those deemed to know best; a truth-spot, one might say, begets public trust and operates, in effect, as a powerful form of localised peer review. There is a bust of the Great Man, wide-eyed and his face alive with curiosity, in the Systematic Garden of the Hortus Botanicus (Figure 7.4a and b). These extensive formal gardens, comprising countless specimens of plants, hot houses, an orangery, and an enormous winter garden constructed from glass and metal, from the upper platform of which the entire expanse can be viewed, were first laid down more than 400 years ago, making them not only the oldest in the Netherlands but also among the oldest such gardens in the world. They are situated just behind the Academiegebouw and extend along the curved bank of the Witte Singel canal all the way to the large observatory that today functions primarily as a visitor and education centre (Figure 7.5). The horticulture-minded visitor will be greeted by a bust of Carolus Clusius, the first prefect of the Hortus Botanicus, in front of the site of the original plant garden. Clusius, another notable whose remains rest in the Pieterskerk, is responsible for making the Netherlands synonymous in the popular imagination with the tulip, a flower that was originally cultivated by the Turks. One of the factors that contributed to the garden’s growing scholarly (and cultural) importance was the collecting of medicinal herbs, plants, and (dried) plant specimens by seafaring employees of the Dutch East India Company; another was the acquisition of the Japanese plants and seeds collection of Philipp von Siebold, whose fostering of East–West ties is commemorated in the tranquil Memorial Garden named after him. The fruits of the Dutch Golden Age are to be found in this urban oasis, which, from the beginning, was ‘not strictly speaking, a hortus medicus, but a genuine hortus botanicus’ (van Uffelen, 2015, p. 15).

∗∗∗

A tour of the botanical gardens brings one full circle to the omphalos, the Academy Building or Academiegebouw. (It is also referred to as the New Academy in order to distinguish it from the Old Academy, namely, the Faliede Bagijnkerk—echoes of Edinburgh, with its Old College and New College.) If Leiden University were to be defined by but one building—which it effectively was until the beginning of the 19th century—it would be the understatedly photogenic Academiegebouw (Figure 7.6). It features on postcards more than any other building in Leiden and is much reproduced in books and brochures. Cloaked in fog or lightly dusted with snow it presents especially well. The building has become a popular symbol of the university and a magnet for visitors, and it is commonly and affectionately referred to as the heart of the university. The church-like structure, made of red brick, is visibly the building of yore, though the steeple and the four gold-faced clocks were added later. High up can be espied a globe, atop which stands sage Minerva.

Each of the university’s seven faculties has a room in the building, and it is here that ceremonial events, celebrations, and receptions take place; that one finds many working reminders of the institution’s past; that one comes face to face, in oil, bronze or alabaster, with many of the great names from the university’s long history. But first impressions can be misleading: the unassuming exterior doesn’t so much as hint at the Gothic Revival sections of the interior, with their high, vaulted ceilings, coloured-tiled floors, and lead-lined windows. In 2009, a sensitive renovation of the building, one that included the use of a palette of old Dutch colours, improved the layout, functionality, and flow of the overall space and introduced contemporary elements without compromising the building’s architectural integrity. The inner courtyard, populated with wall-mounted and freestanding busts of distinguished figures, now has a glass roof (Figure 7.7). Upstairs the barrel-vaulted gown room, with its large, looming portraits of William of Orange and Prince Maurits, houses the robes worn by the professors on special occasions, showcased in glass.

The Senate Chamber, in previous incarnations the lecture room of the Faculty of Medicine and before that the dispossessed nuns’ choir, is a portrait gallery in its own right, the largest non-museum portrait collection in the Netherlands. To be inducted into this particular hall of fame, one has to meet three criteria: to be deceased, to have had a portrait painted by a notable artist, and to have had an excellent academic reputation. This room is also where Ph.D. candidates defend their dissertations. The faces, stacked four deep around the walls, stare down unflinchingly at the formally attired doctoral candidate seated at the long baize-covered table, his ‘seconds’ or supporters—paranymphs, to use the archaic term—at his side, across from the examiners. Behind the inquisitors, there is a large fireplace with a flamboyant chimneybreast bearing the coats of arms of the governors and at its centre a portrait of William of Orange, the omnipresent founder and ‘Father of the Fatherland.’ All in all, it must be an unnerving experience for the student being examined, with, possibly, added stress caused by the presence of family and friends seated immediately behind. The seconds are there to provide moral support, as it were, though in the past their boxing skills came in handy when tempers flared and fights broke out. Outside, the beadle waits, nervously fingering his pocket watch. At the anointed hour, he enters the room and, in time-honoured tradition, proclaims ‘Hora est,’ at which point discussion ceases, no matter who is speaking (Figure 7.8). The defence is therewith concluded. Led by the mace-less beadle, the professors, in full regalia, then recess to deliberate and decide the candidate’s fate. Although it was the case in the 17th century that professors could be fined for failing to wear their robes at public doctoral defences, things have relaxed appreciably since then (Otterspeer, 2008, p. 55). These days an external examiner from afar having arrived sans gown to take part in a Ph.D. defence will have one provided. It’s just like turning up jacket-less at the Ritz.

In the past, degree candidates would wait to take their final exams in the so-called Sweat Room (Zweetkamertje), also known as the Sweatbox, of the Academiegebouw. This single-windowed anteroom, with its bare wooden floor and primitive table, is covered from top to bottom with the multi-coloured hand-written names of students who passed their master’s or doctoral examinations; recipients of honorary doctorates are also eligible to leave their mark. It looks not unlike a mural by Cy Twombly. A ladder rests against the wall for those hoping, futilely, to find a swatch of unmarked space high up. Among the thousands of scratched (on the table) and scribbled (on the walls) names are those of Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill, and the present King of the Netherlands, discretely protected by slivers of plexiglass (Figure 7.9a and b). Inscribed above the entrance to the room are Dante’s words, ‘Lasciate ogni speranza voi che entrate’ (‘Abandon hope all ye who enter here’). To the right-hand side of the door is a cartoon of a visibly distressed, bow-tied student waiting to hear the verdict and to the left another of an elated young man clasping his crisp diploma. It is unclear exactly when this amusing (and possibly unique) tradition began but it is an interesting variation, albeit a more localised and less aesthetically pleasing one, on the red victors plastered on the walls of Salamanca’s colleges and cloisters by its graduating students.

Behind locked doors on the ground floor of the Academiegebouw is the Great Auditorium, with its modestly sized pipe organ, rows of wooden benches, and, along the sides and rear, stalls marked variously ‘Doctoren,’ ‘Professoren,’ ‘Lectoren en Privaat-Docenten,’ ‘Rector Magnificus,’ and ‘Pedel.’ One knows one’s place, literally and figuratively, in this formal setting, which retains the look and feel of the chapel that it once was. Standing on a podium beneath a wooden canopy in front of the assembled ranks of colleagues and guests, the newly appointed (full) professor delivers his inaugural lecture, laying out his scholastic stall as it were, before exiting the chamber for a much-needed libation and well-deserved encomia in the adjacent reception area.

∗∗∗

From the outset, Leiden University was closely connected to both the city and the larger environment, governed as it was jointly by three curators, appointed by the States of Holland, and a quartet of city burgomasters. Leiden was not, and still is not, a collegiate university: students have always lived in lodgings and rental accommodation throughout the city, making them an integral aspect of community life. At one time, the university even had its own law court, which had the right to deal with cases involving persons connected to the university. In some respects, Leiden was not altogether unlike the University of Edinburgh, founded only 7 years later, which from its very earliest days had an intentionally civic character. Governance at Leiden was not always straightforward, and ‘the condominium of town and university’ (Jurriaanse, 1965, p. 14) resulted in friction. Tensions surfaced recurrently between the States, the city, and the professorate in the formative decades as each group of stakeholders sought to exercise control over the allocation of resources and the appointing of professors. As elsewhere—the University of Salamanca, for instance—town and gown did not see eye to eye on the issue of privileges. The local citizens took exception to the exemptions granted to members of the university community from toll charges and taxes on alcohol as well as to exemptions from military service. Such indeed were the perquisites of student life that a lucrative underground trade in some of these privileges developed (Otterspeer, 2008, p. 38). As was so often the case in the history of Europe’s early universities, bubbling resentment in Leiden boiled over into physical violence to such an extent that the States of Holland and the City of Leiden jointly approved and co-financed a student militia to maintain nocturnal law and order. But early tension gradually ceded to harmonious co-existence, and by the 19th century the bond between town and gown had strengthened: ‘There were nearly always three or more professors sitting on the city council’ and ‘[n]ot a single school or almshouse existed that did not have professors on its board’ (Otterspeer, 2008, p. 183).

Nevertheless, relations between town and gown were at times strained by the social differences that existed between the parochial local population and the cosmopolitan student body, ‘diverse in terms of religion and primarily upper-class’ (Otterspeer, 2008, p. 41). It is no secret that the offspring of the country’s upper crust have long favoured the university. The various student associations, though organisationally somewhat different from one another, have much in common with fraternities at American universities, not least in terms of their penchant for partying, pranks, and sartorial conformity: groups of blazer-wearing young men breeze through the streets of the city, by day and night. Social networking remains the defining purpose of such bodies on both sides of the Atlantic. L.V.V.S. (Leidse Vereniging Voor Studenten) Augustinus, one of the oldest societies at Leiden and housed on the Rapenberg diagonally across from the Academiegebouw, grants occasional admission to non-members and international students. L.S.V. (Leidse Studentenvereniging) Minerva, a large fraternity cum sorority with flag-bedecked premises in Breestraat, is traditionalist and elitist in nature (Figure 7.10). These and other student societies, such as Quintus (motto: ‘Diversity and Tolerance’), are made up of many sub-sections, reflecting the social, cultural, and recreational interests of their members. Every August they reveal their true colours during EL CID, a week of bibulous excess that welcomes new students to Leiden and introduces them to canal-side living. Think of it as the Dutch equivalent of Raisin Weekend at the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

Leiden University, though blessed with some captivating aspects, is not a serious contender in the global pulchritude stakes. But it also does not aspire to be an Oxford or a Salamanca. From the earliest days, the university secured space and premises where it could and adapted these to its needs, a recent example being the airy architectural conversion of a former arsenal, now home to East Asian Languages and Culture (Figure 7.11). The university’s buildings, classrooms, laboratories, departments, administrative offices, and research centres are scattered around the city, and to the casual eye there is little evidence of integrated design or an institutional master plan, though the ubiquitous logo, on windows, signs, walls, and doors, does at least ensure that the institution is never far from one’s mind. Many humanities departments are to be found in the area bounded by Witte Singel and Maliebaan, at the hub of which is the main university library: domed, low-slung, and equipped with considerable subterranean capacity. Hereabouts, large tracts of stained concrete, red brickwork, and glass combine to create a somewhat harsh modernist landscape that does not benefit from the use of a strange, funnel motif throughout. One could be on a campus almost anywhere, but for the nearby canals, pretty wooden footbridge (the Paterbrug), forests of parked bicycles, and the occasional glimpses of both the observatory and the tower of the Academiegebouw in the near distance.

The attractiveness of Leiden University is due in no small measure to its picturesque host city, the birthplace of one of the masters of art. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leiden in 1606, of humble stock, and there attended the Latin school, as boys of that era did before enrolling at university. Visitors will find the gabled schoolhouse with its red-tiled roof just off the Het Gerecht, a cobbled square in the heart of the old city. Diagonally across from the school is the looming Gravensteen, a university building that was formerly a prison and the site of many executions (Figure 7.12). A returning Rembrandt would feel very much at home, though possibly surprised to find a replica desk and mannequin in the window of the commercial premises that have since replaced the school of his youth. With the notable exception of his family abode, which was unceremoniously demolished by the city in the early part of the last century, the defining landmarks of his era are mostly extant and recognisably themselves, renovations and re-modelling notwithstanding: the adjacent Pieterskerk, which dates from the 12th century, and Leiden University’s emblematic Academiegebouw, a couple of hundred yards away across the canal on the Rapenberg. Rembrandt matriculated in 1620, some 45 years after the founding of the university, to study Science and Anatomy, but the call of the canvas was too great for the then 14-year old, and he thus became the institution’s most distinguished dropout—Leiden’s early version of Harvard’s Bill Gates.

In the Gravensteen, faded, polychromatic wall drawings of religious themes made by former residents (prisoners, to be precise) can still be seen. The building is a slightly chaotic clump of congealed structures of very different architectural styles that have evolved over the centuries. From the Pieterskerk Hof one sees a building with a handsome classical façade, the bricked-up windows notwithstanding. Viewed from the other side (which would have been Rembrandt’s view from his schoolroom), the two towers become clearly visible along with a gallery and a classically proportioned townhouse slightly off to one side. The overall structure has been renovated but not to the extent that its original purpose cannot be divined. For instance, you’ll see an idle torture device standing tall in an interior courtyard. The oldest parts, the tower and the dungeon below it, date from the Middle Ages. In 1555, an additional prison with four tiny cells was constructed. These cells, which have dense stonewalls, narrow windows and heavy-duty, multiply bolted doors, now function as seminar rooms, albeit of a claustrophobic kind. On the small table there is a computer, evidence of modernity, on the curved ceiling the very hooks from which prisoners once dangled while being subjected to torture. The overall effect is disconcerting. The gallery was the spot from which sheriffs, magistrates and the nobility would watch executions taking place in the courtyard, a spectacle much enjoyed by the local populace and grounds to cancel classes, somewhat to the annoyance of the academic authorities (Figures 7.13 and 7.14). The past is ever present in the Gravensteen. No wonder some people feel genuinely spooked by the place.1

∗∗∗

A quite different kind of architecture is to be found in the sleek contours of the Oort Building and Huygens Laboratory on the Niels Bohrweg, home to the Leiden Institute of Physics. This newer part of the university abuts the enormous Leiden Bio Science Park and the Leiden University Medical Center (home to an anatomical museum), a hypermodern mix of Big Pharma and higher education on the other side (literally) of the (railway) tracks, far removed in every sense from the Academiegebouw and the historic core of the university (Figure 7.15). (Willem Otterspeer [2008] actually speaks in C.P. Snow-like terms of the ‘sharp split between the two cultures embodied by the railway line’ [p. 236] that bisects the city.)

On the wall of the Huygens Laboratory are signatures of distinguished physicists (Max Born, Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Erwin Schrödinger, and many others), a testimony to the university’s numerous contributions to the development of the field in both modern and pre-modern times. Eminent colloquium speakers may be invited to leave their mark on the glass-protected surface (Rickman, 2008). The inscribed wall was formerly in a laboratory named after Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, the experimental physicist whose pioneering work into the properties of matter at extremely low temperatures—he was the first to liquefy helium—won him the Nobel Prize in 1913.

But Leiden was making major contributions to physics long before then. Indeed, the university was one of the very first in the world to incorporate experimental demonstrations and the use of specialised instrumentation into the teaching of the subject. (The material truth of that statement can be witnessed in the Boerhaave Museum, which contains a trove of scientific instruments, from astronomical quadrants and steam pumps to microscopes and handcrafted surgical instruments.) Much of the credit for the introduction of the new ‘physica experimentalis’ goes to Professor Burcherus de Volder, who was influenced by practices he observed at the Royal Society of London during a trip to England in 1674 and insisted they be adopted at Leiden. Gradually, in Leiden and elsewhere, Newtonian physics replaced Cartesian modes of thought, with the new empiricism trumping philosophical speculation and metaphysics (Luyendijk-Elshout, 1975).

Onnes was not the only Leiden professor to be awarded the Nobel Prize for physics. Hendrik Antoon Lorentz, who came to the university at age 16 and earned his Ph.D. five years later, was appointed to the Chair of Theoretical Physics at the precocious age of 24, and during the course of his career made significant contributions to a variety of fields, ranging from hydrodynamics to general relativity. In 1902, he was honoured with the ultimate prize for both his experimental and theoretical work. Each year the university invites an eminent visiting academic to hold the Lorentz Chair at the institute named after him. By way of an aside, universities are understandably keen to be associated with Nobel prize winners, though there is little standardisation in terms of accounting. The individual may have been an undergraduate at institution A, completed a Ph.D. at B, spent some time as a post-doctoral researcher at C (as, for example, future Nobelist Enrico Fermi did at Leiden in 1924), held successive full-time academic appointments (whether before or after the prize-winning contribution or, indeed, the actual conferral of the award) at D, E, and F and over the course of a career have held visiting professorships, of varying duration, at G, H, I, J, and K. That being so, one should not be altogether surprised to find all 11 universities proudly listing said prize-winner among the ranks of their distinguished alumni, scholars and visiting professors. Basking in glory-by-association is perfectly understandable, but there is more to it these days, as the number of Nobelists linked with an institution may influence public perceptions and international rankings.

When Lorentz retired from his chair at Leiden, he had hoped to recruit Einstein as his replacement, but it was not to be. Ironically, Einstein had written some years earlier to Onnes asking for a job at the university but apparently his letter remained unanswered. The professorship went instead to Paul Ehrenfest, who, as it turned out, became a close colleague and friend of Einstein, following the latter’s first visit to the university. In 1920, Einstein was officially appointed to a three-year visiting professorship and delivered his inaugural lecture on October 27, 1920. The April 2006 cover of Physics Today featured a picture (caption: ‘A Leiden duet’) on its cover showing Ehrenfest at the piano and Einstein standing playing the violin. Onnes’s nephew, Harm, an early member of the art group De Stijl, which was founded in a house near Rembrandt’s birth spot, painted several portraits of Einstein during his sojourns in Leiden. Apart from his own formal contributions to physics, Ehrenfest deserves a pat on the back for housing Niels Bohr and Einstein in adjacent bedrooms on the top floor of his house, ‘where they moved quantum mechanics forward through daily arguments’ (Kuper, 2006).

∗∗∗

Leiden has always been a civilised city, one that reveres literacy and libraries (Hoftijzer & van Ommen, 2008). In 1587, various members of the Elzevier family established a bookshop and printing business in a house immediately adjacent to the university; the building is long since gone, but it can be seen in engravings of the period and, specifically, in Hendrick van der Burgh’s c. 1650 jolly painting A Graduation Ceremony at Leiden University. In the 19th century, the modern scholarly publishing behemoth Elsevier (no relation to the Elzevier family) took the original business’s name along with its Non Solus printer’s mark.

The city’s reverence for the scholarly and literary extended to the university, and efforts were made to recruit big names. In 1578 the noted humanist Justus Lipsius was appointed to the Chair of History. He was viewed widely as the embodiment of the university’s ideals and served for a period as Rector Magnificus. (Lipsius, in said role, appears in the group portrait, The Four Philosophers, by Peter Paul Rubens.) In 1593, the university recruited another renowned humanist, Josephus Justus Scaliger, who accepted an offer to join the ranks of the faculty with no formal obligation to either teach or participate in university meetings. He was not the only one to be lured in such fashion at the time: the botanist Clusius and the classicist Claudius Salmasius were also paid more than double the regular professors. Scaliger was even referred to, and with no disrespect intended, as an ‘ornament’ of the university (Otterspeer, 2008, p. 45). He was what today would be called an ‘academostar’ (O’Dair, 2001)—the kind of highly productive, highly cited, highly visible professor whose name adds lustre to the hiring institution and whose reputation, by the same token, grants him or her considerable bargaining power. Scaliger quickly became a powerful magnet for scholars and students from all over the continent, a case of money well spent as it turned out. Scaliger’s name lives on in the shape of the Scaliger lectures and the Scaliger Institute, which was founded in 2000 as a centre for the study and use of the university library’s special collections. Although Scaliger is on record as having described the city of Leiden as a ‘swamp amidst swamps’ (van Ommen, 2009, p. 3) and its inhabitants in terms they would probably not wish to have heard, this ‘sixteenth century Einstein’ who was granted the right to wear his princely red gown by the university remained there until his death (van Ommen, 2009, p. 3). Some of his books were donated to the library; the university posthumously acquired others.

Another bibliophile and philanthropist of note was Johannes Thysius, the son of a rich merchant, who earned both a bachelor’s degree and a doctorate at the university before dying at the young age of 31. In his will, he left his collection of 2,000 books along with a large sum of money for the purpose of establishing a public library on the Rapenburg Canal. The library, a fine building in the Dutch classical style and one of the country’s Top 100 heritage sites, was completed in 1657. Today, admission is by appointment only, which may not quite be what the benevolent Mr. Thysius had in mind (Figure 7.16).

Despite the best of intentions at Leiden, the ideals of rational enquiry and intellectual tolerance were not easily or always attained: in the early 17th century, the precisians asserted their authority over matters of ideology and curriculum and eased out some of those of whom they disapproved. When it came to religious doctrine and the teaching of philosophy, disputes were agonistic, at times requiring formal mediation. In the middle of the 17th century, the Curators of the University prohibited the name of René Descartes from even being mentioned, whether in opposition to or in defence of his views (Woltjer, 1975, p. 7). Coincidentally, the great philosopher lived in Leiden for a time and enrolled as a student in 1630 (6 years after the Black Plague had decimated the population) in order to gain access to the university library collections and to attend lectures on mathematics and astronomy. A plaque identifies the canal-side house on the Rapenberg (No. 21) where he lodged. And it was in Leiden that Descartes’s influential Discourse on the Method was first published. During the Dutch Golden Age, loosely co-extensive with the 17th century, the university developed into an acknowledged powerhouse of humanistic scholarship (Theology, International Law, Arabic Languages and Culture) and became a major site of advances in both science (Botany, Physics) and medicine (Anatomy, Physiology).

∗∗∗

Leiden University, like every institution, has had its good days and bad days. One of its darker moments occurred during World War II when the occupying Germans expelled Jewish professors. Their colleagues, most notably Law Professor Rudolph Cleveringa, stood tall in defiance, the students went on strike, and the peeved Germans retaliated by closing down the university and tossing Cleveringa in jail. On the bright side, the university had, and was seen to have, lived up to its motto (‘Bastion of Liberty’) during that difficult period. Today, Leiden University shows little sign of resting on its laurels, having grown enormously during the second half of the 20th century, and not just in terms of its physical plant. Student numbers climbed from under 3,000 in the 1940s to almost 18,000 by the mid-1990s, by which time there were as many female as male students. Expansion has continued on all fronts since then. In recent years, the university has established a permanent campus (Leiden University College) in The Hague, offering courses in subjects such as Public Administration and International Relations, Peace, Justice and Sustainability. These have proved to be extremely popular with both Dutch and foreign students, and expanding enrolments have triggered major construction projects. Back in Leiden, ground was broken in 2013 on the first phase of a new science campus, which will collocate the various research institutes of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences. When the project is completed in 2022, the gross floor level of the purpose-built, mini campus will be 100,000 square metres. Boerhaave, Eherenfest, Lorentz and Onnes would all doubtless approve and also be amazed at the sophistication of the facilities. But resting on its laurels would, one imagines, be especially difficult for a university that is itself responsible for one of the most influential rankings of universities worldwide, the eponymous Leiden Ranking, produced annually by the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (www.socialsciences.leiden.edu/cwts/products-services/leiden-ranking.html), an acknowledged centre of excellence for quantitative studies of science. This is one university that can hardly fail to look itself in the mirror.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.