What Is Being Done Elsewhere

As we have seen, the concept and construction of the cellular telephone system offers a solution to some of the ever-growing telecommunications problems of the densely populated, highly industrialized countries of the western world with their increasingly mobile populations. As an example, on many of the inhabited islands along the coasts and fiords of the Scandinavian countries of northwestern Europe, travel by boat is essential for business and pleasure and is as common as travel by automobile is in the United States. High costs and technical difficulties have hampered the expansion of the public wireline telephone service to these islands, most of which lie in the North Sea just off the mainland. The installation of a cellular system covering these areas, for use by portable and fixed stations in homes on the islands and by mobile units in boats and cars, expands the communications horizon for these citizens who live offshore. In Sweden, more than 11% of the population have cellular telephones; in Finland the figure is 10.7%; in Norway it is 10.5%; and in comparison, in the United States (in 1995) the figure was 7.4%.

As of mid-1994 there were some 41 million cellular telephone subscribers, worldwide, using 192 service installations in countries such as Algeria with 12,000 subscribers, and in Zimbabwe where installation of their first cellular system had just begun. However, the future promises tremendous growth. In the European countries alone, 50 million cellular telephone subscribers are expected to sign up for service by the year 2000. It has been predicted that by then there will be more wireless telephone subscribers, using the global system for mobile use (GSM) and the conventional cellular systems, than those who are connected to the conventional wired telephone systems.

For lesser developed countries the cellular concept offers a method of linking together those large and small population centers that are too far apart to economically connect by wire. No country can develop its resources and grow successfully without a reliable and rapid means of communication available at a reasonable cost to all of its citizens. In the United States this came about through the invention and early popularization and use of the telegraph and then the telephone.

The telecommunications industry in the United States has always been in private hands but has been strictly controlled by government regulations. Nationally the industry is controlled by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), in the states the Public Service Commissions exert control, and local jurisdictions control with their building and zoning boards. That was the situation up to now, but as described in the previous chapter, the regulatory picture is changing.

In Europe and most of the rest of the world, the telephone and telegraphs systems had always been a tightly held government monopoly. In the 1980s, the political climate began to change and a trend toward the partial, if not complete, privatization of telephone monopolies in most countries began. These governments also began to allow competition from private companies in the telecommunications industry. In Europe, in addition to the above changes, there came the effects of the European Union (EU) and its attempts to provide standardization and regulations in all fields, including telecommunications, that would apply to all of the member countries on the continent. It is not yet clear how this concept will mix with the very strong national pride that exists in most of these countries. There may be problems and conflicts with the long-standing national regulations in those countries where the ownership of the telecommunications industry that is to be covered by EU regulations varies from being fully privatized in some countries, to being one-hundred percent government owned in others.

To be completely satisfactory, a national telephone system must be simple, inexpensive, and flexible enough so that it can be used in both urban communities as well as in the less densely populated rural areas. A cellular system appears to meet most if not all of these requirements. Single cells, each covering areas up to twenty miles across in sparsely populated areas or small urban centers, can be linked together into a country-wide service by the use of microwave relays. This eliminates the need for erecting poles, stringing wires, or laying the cables of a conventional hard-wired telephone system. In some types of terrain, the usual construction methods are impossible: large swamps or wide river deltas are obvious examples. Many villages in some of the tropical countries needing some type of communication with the outer world, are built on such ground.

There is added flexibility to cellular systems in that the radio frequencies used for communication can be selected according to the conditions that will be encountered. The lower frequencies, 400 MHz for example (as was used in some of the early systems in Europe), can cover longer distances between cell sites and give better foliage penetration than the higher frequencies of 800 or 900 MHz. This may be an important factor in some tropical countries where jungles and rain forests are frequently encountered. This 400-MHz frequency band was never considered for cellular telephone service in the United States. By the time the FCC got around to looking at cellular communication and authorizing its use, the 400-MHz portion of the spectrum was already filled with other users and services.

Once the local regulatory and zoning problems have been overcome, the physical components of a cellular system are relatively quick and easy to set up and put into operation compared to a wireline system. Nearly everything can be preassembled prior to installation. Where electrical power is not available, a bank of batteries, kept charged by solar cells or fossil-fueled generators, can be used to provide the necessary power for the equipment at the cell sites. Completely packaged cell sites, fitted into a van or trailer, are available for use in isolated areas. Where needed, individual cellular call boxes or kiosks can be set up in village squares or along major highways, again using solar power to charge the batteries needed to operate the telephone. This practice can be adopted in urban areas, too. In Mexico, for example, plans have been made to install some 500 stand-alone public telephone kiosks using cellular telephones.

It is the prior planning, as you have seen, that takes time. Evaluating the terrain and making propagation studies, either on the ground or through the use of specially prepared maps of terrain data and then running the on-the-ground confirming tests, all take time.

The first generation of cellular systems tended to be “national” in design and construction using software and hardware developed by the industrial telecommunications sources in each country. In the United States, the first system was called the Advanced Mobile Phone Service (AMPS); in Scandinavia it was Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT); in the United Kingdom, Total Access Cellular System (TACS); and a cellular system in Japan, Nippon Telephone and Telegraph (NTT), was developed by Japanese telecommunications interests and so on.

None of these were compatible. In Europe, for example, travelers going from England across the English Channel to France, or visitors from France crossing the border into Germany could not use their cellular telephones once they had crossed into another country. In Europe the telecommunications services were government owned and controlled and feelings of national pride stood in the way of too much cooperation at first.

This lack of coordination in communication matters became a source of irritation to business travelers. As commerce became more and more international, particularly with the growth of the European Union and the impact of regulations and rule-making beginning to be felt, the need for a compatible, all-over cellular system became urgent. This need was also fed by the great increase in cross-border travel by holiday makers to vacation spots on the continent or in United Kingdom.

The trend toward the privatization of the European government-owned and controlled telecommunications services in the 1970s and 80s, combined with the expansion of the telecommunications equipment industry to cover countries worldwide, eased the transition to a common system. One of the first tasks of the newly organized European Union was to set up the European Commission (EC) to run the new organization. This was essentially the “civil service” of the community, the units and people that did the work. Then Directorates, covering the various fields of common interest such as agriculture and fishing, were organized under the Commission. Directorate DG XIII, for example, was set up to organize “Telecommunications, information industries and innovation.”

One of the main objects of the EC was the standardization, “harmonization” as they called it, of goods and services so that they could flow freely throughout the countries of the European Community. The standardization of telecommunications systems and equipment was an important part of this effort and it led to the establishment of the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI). This is an organization of industry/government groups designed to accomplish standardization of existing wireless communication systems and equipment throughout the countries making up the European Community.

A second generation cellular system, using digital techniques, called Global System for Mobile Radio (GSM), was developed through the efforts of ETSI and has become the standard system in Europe. With a common cellular system and contractual agreements regarding roaming service between countries and carriers, a traveler now can use a cellular telephone all over the European continent. Billing information is exchanged through a central clearing organization so that the international user pays everything through their home service.

GSM was originally planned for telecommunications use in Europe and was developed through the coordination of industry and intergovernmental agreements, as has been said. This is a digital system, which operates in the 900-MHz band in Europe. Because it is digital, it takes up less room in the spectrum and gives more capacity to the system operator. It is also less likely to suffer from interference. Eavesdropping and cloning, problems that have been described and that particularly plague analog cellular signals, are practically eliminated with the digital signals. GSM systems are now being introduced into countries all over the world. Of the 192 cellular telephone installations that were in place throughout the world in 1995, about seventy of them are GSM systems. This system has been adapted for use in the first 1,900-MHz personal communications systems (PCS) coming on-line in the United States.

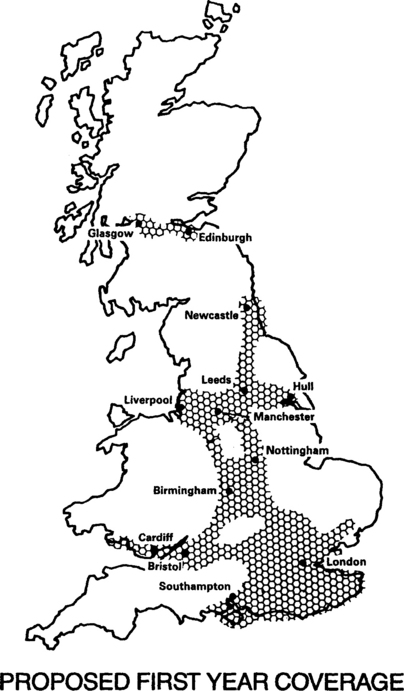

An example of typical growth in Europe is illustrated in Figure. 8-1. It can be seen that the original system of one of the English carriers was designed to provide service in only the major business centers and on the main highways connecting them. Service was also planned to cover the heavily urbanized southeast area of the country. The present coverage now, with some 3,000 cells, covers about ninety-eight percent of the country, including some of the offshore islands in the North Sea, off the coast of northern Scotland.

Typical cellular penetration rates in Europe, the percentage of the population that owns and uses a cellular telephone, are about six percent for the United Kingdom, two percent for France, and four percent for Germany. The higher rates of penetration for the Scandinavian countries have already been discussed. Like everywhere else in the world, these figures will go up as the price of the instruments and the cost of the service goes down.

Similar growth patterns exist in the rest of Europe where, as in the United Kingdom, the original plans to cover only the main urban areas and the connecting highways had to be changed and greatly enlarged to include entire countries as the use of cellular telephones grew. And in Eastern Europe, as in the old East Germany, the installation of cellular systems is overtaking the conventional wired telephone systems.

In Asia, cellular service is growing, too. In Australia, there are some three million cellular telephone users, while in the busy, highly urbanized, commercial center of Hong Kong there is a penetration rate of six percent. In China there are some 11 cellular services, rapidly expanding coverage throughout the provinces and the country, serving over a million subscribers at the present time.

Japan, who introduced a cellular telephone system in 1977, was the first country with such a system. Now they have approximately 4.3 million subscribers. Another system that is coming online is Personal Handyphone System (PHS). It will operate digitally in the 1,900-MHz band and is somewhat similar to the recently introduced PCS systems in the United States. The Japanese PHS handset can be used in and around the home as a normal cordless telephone, accessing a base wireless unit that is installed in the house and connected to the local wired telephone network there. When used outside of the house and out of range of the home unit, the instrument performs as the usual cellular telephone by connecting with cell sites that are installed around the area. There are fifty thousand base stations installed in Tokyo. The range for these handsets is 100 to 200 meters or 300 to 600 feet. Japanese authorities estimate that the system will have about thirty-eight million subscribers by the year 2010. This is very similar to the system described in Chapter 3.

The countries of Central and South America all have cellular services and are expanding them as their economies grow. For example, Mexico has some 400,000 subscribers, and in Brazil, where there has been service since 1990, there are over 600,000 cellular users. In Argentina there are 200,000 users.

Until there is a universal cellular system, providing worldwide service with just one handset, there are one or two options available to travelers who want to use a cellular telephone when traveling overseas. If you are going to an area with a GSM cellular system, you can rent a handset that is compatible with the GSM system from a company that specializes in this service, before you leave the United States. The GSM cellular calling number will be already assigned to your instrument so that you can pass it on to people in your office and to your family before you leave. The instrument will be delivered to your hotel or to you at the airport. In Europe, the service will be through one of the United Kingdom cellular carriers and is good for roaming in some twenty-three European countries at the present time; there will be more in the future. If you run into any problems there is a twenty-four hour service number to call for help. This sort of service is also available in some of the Asian countries, including Australia, and in the business centers of Singapore and Hong Kong. It can be seen that the ability to communicate with anyone anywhere will no doubtedly expand as commercial markets open up and grow in other countries, and the number of travelers to these countries increases.

Another service, operating along a different line, for cellular users who travel overseas has been developed. The company providing this service does not deal directly with the user, but the service is wholesaled to your local cellular carrier. The local cellular carrier then sells this service to you and bills you for your overseas calls through your normal billing channel. This is done in a manner similar to the long distance service resellers that are in the market today who buy up blocks of time at a discount from the long distance telephone companies and then sell this service to you. The big advantage of this type of service is that anyone phoning you will use your local cellular number to reach you no matter where you are located, in the United States or abroad.

To take advantage of this service you must notify your local cellular carrier that you are traveling overseas and want to use a cellular telephone while you are away. You will then receive a handset that will be compatible with the service that is in use where you will be traveling. You will also be given a subscriber identity module (SIM). This is a “smart card” that is programmed with your specific cellular profile and personal data. This card is slipped into the telephone handset for use when you are overseas. Imbedded in this card is the information that tells the local U.S. cellular service that you are in your overseas location and that you are a valid roamer with an authorized ID.

If someone back at home or in your office wants to call you, as we have said, they use your local cellular number. The mobile telephone switching office (MTSO) of your local carrier, having been made aware that you are now using this overseas service, switches the call to the overseas service provider who locates you via the cellular service in the area in which you are located. The service will also work in reverse for those visiting the United States from Europe and Asia. Dual-mode instruments are under development and on the way. It is planned that these handsets will be capable of working with either the GSM service overseas or the advanced mobile phone service (AMPS) service in the United States. Instruments like this will be very useful for frequent travelers to overseas destinations.

As further evidence of the growth in the general acceptance of the use of cellular telephones, there is now a hotel in Paris in which a cellular telephone handset is automatically provided with your room. The cellular telephone number is given to you and the handset is activated for your use when you check into the hotel. The service is through one of the French cellular carriers.