10

Stakeholders and investors

This chapter outlines how to identify, prioritize, and engage with external stakeholders to add value to your corporate responsibility program.

Feedback is a gift (source unknown).

When I started my career in environmental management in the mid-1980s, the term “stakeholder engagement” did not exist. Today, there are businesses built around providing your company with this essential aspect of your corporate responsibility program.

There are several schools of thought about engaging stakeholders in your program, and like so many things in the sustainability/corporate responsibility field, the definitions can be vague and imprecise. Let’s start with a definition of stakeholder engagement:

Stakeholder engagement is a formal process of relationship management through which companies or industries engage with a set of their stakeholders in an effort to align their mutual interests, to reduce risk and advance the triple bottom line – the company’s financial, social, and environmental performance.69

At its essence, stakeholder engagement is really about getting input on your program goals, progress, and plans. Because the reputation of your company is a hallmark of success for your corporate responsibility program, it makes sense to identify the stakeholders who influence your company’s CR reputation and invite them to participate in your program. In the process you will build relationships with these individuals and groups and gain valuable insights for shaping your program. This chapter will delve into these rules of engagement and give some specific examples of effective practices.

There are several ways to engage with your company’s stakeholders, ranging from somewhat passive means (e.g., suggestions received on your company’s website) to a formal standing advisory panel. While there are a myriad of variations for engaging stakeholders, this chapter will cover practical advice for formal engagement (e.g., stakeholder panels) and informal engagement (e.g., consulting with a few external contacts) that you can adapt to your circumstances. While your company’s employees are an important stakeholder group, this chapter is solely focused on stakeholders who are external to your company (employee engagement is covered in Chapter 11). Also, I deliberately distinguish the socially responsible investment (SRI) community from other stakeholders because there are some unique aspects of engaging with this segment that warrant additional advice covered later in this chapter.

Who are stakeholders?

A stakeholder is any group or individual that has the ability to impact and/or that may be impacted by your company’s operations and/or policies. Stated another way, a stakeholder is an entity that has a legitimate social, economic, political, or environmental “stake” in your company’s activities. The term “stakeholder” was once more narrowly defined as shareholders, regulators, employees, and customers. Today, as a result of changing expectations, stakeholders comprise a much broader set of constituencies that must be defined on a case-by-case basis for the particular circumstances of your company.

Stakeholders may include:

• Ownership interests. Investors, partners, shareholders, analysts, and ratings agencies

• Customers. Business customers, consumers, and consumer advocates

• Employees. Current employees, potential employees, retirees, and labor unions

• Value chain and operational support. Suppliers, contractors, and service companies

• Industry. Industry associations, industry opinion leaders, and competitors

• Community. Residents near company facilities, chambers of commerce, resident associations, schools, community organizations, spiritual communities, special-interest groups, and indigenous peoples

• Civil society. NGOs, activist groups, charitable associations, and clubs

• Government. National or federal policymakers, state policymakers, local policymakers, regulatory and tax authorities, and customs officials

• Multilateral organizations. Examples include the United Nations, World Bank, and the International Finance Corporation

Formal stakeholder engagement

Formal stakeholder engagement involves establishing a committee that you will work with over the long term, either on a particular project or as a standing advisory board to provide general input for your program. This type of engagement carries the most overhead in terms of governance procedures, ground rules, and operations, but it can also provide the biggest benefits to your program. The principal benefits of operating a formal stakeholder panel stem from the relationships you will build by working with a committed group of people over a longer period of time. The stakeholders will gain a deeper understanding of your company and the issues you face. This understanding, coupled with their diverse perspectives, will provide insights and guidance that can help guide your program. Also, if your company encounters difficult issues, the stakeholders on your panel will be well positioned to comment on your behalf because they will be invested in your program and knowledgeable about your strategies.

Project XL

In the mid-1990s, I was involved in one of the early environmental programs based on formal stakeholder engagement. The program was called Project XL, which stood for “eXcellence and Leadership,” and was a cornerstone of then Vice President Al Gore’s “reinventing government” initiative. The basic idea was to develop a process to improve environmental performance while reducing government bureaucracy. The projects that were authorized under this program featured formal stakeholder committees to engage in the decision-making process and oversee the performance. Because this project broke new ground in the arena of stakeholder engagement, it is a useful model to extract a few salient tips for formal stakeholder engagement today.

Intel submitted a proposal focused on a facility still under construction at the time, called Fab 12 in Chandler, Arizona.70 The essence of the proposal was that all of the facility’s air emissions would be totaled up and reduced so that the total pollution from the facility would be significantly less than the regulations would require. In exchange for this added level of environmental protection, Intel would not have to seek additional permits each time the manufacturing process changed. The project included a stakeholder panel that would be intimately involved in defining the final agreement as well as overseeing implementation.

To identify the stakeholders for this panel, Intel started with the existing community advisory panel (CAP) that was made up of neighbors, local activists, and local regulators. The CAP appointed members from their ranks that had an interest in environmental issues to the stakeholder panel. In addition, Intel made sure that each of the federal, state, and local regulatory agencies with a relevant oversight role was represented on the panel. Finally, because this was a precedent-setting project, Intel invited some national NGOs to participate as well.

As the group came together, they had to define their roles and responsibilities. There were long debates over whether the stakeholders on the panel would need to be in full consensus (unanimous agreement) or whether a majority vote would suffice. Consensus was considered problematic because it essentially gave veto rights to each panelist. I recall my boss at the time, Larry Borgman, had a phrase that encapsulated stakeholder roles, which he dubbed “the four Vs.” This stood for “View, Voice, Vote, Veto,” and his belief was that stakeholders should have the first two but not the second two Vs.

The panel eventually decided to use a “group consensus” process to reach decisions. This meant that each of stakeholder categories had to agree. In other words, all of the panelists were assigned to groups, such as NGOs, local residents, regulators, and Intel, and each of these groups got one vote. If any group objected, the vote would fail. This allowed consensus to move ahead even if one member of the panel objected but their group was in favor.

The ultimate success of this project was due, in no small measure, to our very talented facilitator, the late Chuck McLean who, despite constant veto threats and charged emotions on this project, brilliantly led the team to consensus on every tough issue.

The stakeholder panel broke into sub-teams that met at least monthly to work through each aspect of the permit. Because the issues we were discussing in these groups were technical, Intel funded independent technical analysts that were chosen by the stakeholders to help them understand the concepts and thus be more fully engaged. Intel also contributed funding to cover the expenses for some of the stakeholders.

This stakeholder panel was ultimately successful in producing a final agreement that allowed Intel to operate without changing its operating permit, significantly reducing the facility’s environmental impact. Because the permit capped the total emissions from the site, Intel was motivated to develop innovative ways to keep emissions under that threshold so that they could continue to expand their operations without triggering time-consuming environmental permitting processes.

The panel stuck together for more than a decade after the project was approved to oversee implementation. During that decade, Intel was able to build two additional factories (at a capital expense in excess of $6 billion) on that site without ever changing the permit negotiated under Project XL. This level of flexibility is unprecedented for environmental permitting and resulted in significant savings in time and money for Intel.

Establishing a stakeholder panel

Below are a few important principles for establishing and operating a formal stakeholder engagement panel:

Define the reasons to engage

Not every company, program, or project needs a formal stakeholder advisory panel. Operating these panels is time and resource intensive and thus you should use them only in certain situations. Circumstances are appropriate for formal engagement with a stakeholder panel when:

• Your company is developing a new strategy and/or goals

• Your company is changing its business model or building a new facility

• You want to significantly revise your corporate responsibility programs

The common element in these cases is that your company is experiencing significant change, seeks input, and is open to act on the advice. If you are more interested in getting the credibility that comes with engaging stakeholders or just testing the waters to get reactions to your programs, a formal engagement model is not recommended and may backfire.

Find a facilitator

I highly recommend starting with a talented facilitator. When seeking independent perspective and opinion, a third-party facilitator can help guide the process so that you get true diversity of perspective and influential opinions. I have used Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) while at Apple and, more recently, Ceres at AMD – both are excellent at establishing and facilitating stakeholder engagement processes.

Identifying stakeholders

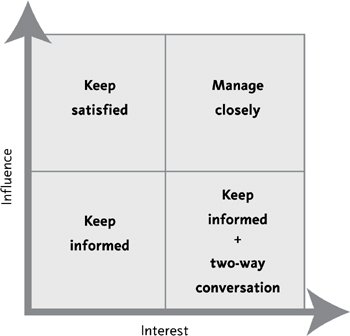

Often called “stakeholder mapping” the 2x2 matrix in Figure 6 sets out the generic process you can apply to identify your stakeholders. Again, this is a process that is best conducted with a third-party facilitator because it takes you out of the role of “hand-picking” your panel. The people and groups in the top-right corner of the matrix – those who are both interested and influential – are the best candidates for a formal panel. This is not to say that other segments of the matrix are unimportant. The matrix is only a guide to establish priorities for how to interact with different groups of stakeholders.

Stakeholder mapping works well when you have already identified the “material issues” in your corporate responsibility strategy (see Chapter 3) because your facilitator will be able to match the stakeholder interests to these issues. Of course, you may also engage stakeholders to guide you in the process of selecting material issues, but the makeup of the group may change based on the issues selected. Typically, your team will work with the facilitator to put names of people and groups into the matrix in Figure 6.

Figure 6 Stakeholder mapping matrix

The matrix illustrates four categories of how your company might choose to engage with various stakeholders. There is a continuum of engagement methods that ranges from “ignore” to “partner,” but for this example, we are looking for the people/groups to join an advisory panel (the “manage closely” quadrant of the matrix). In many cases, the stakeholder groups to invite to the panel will be obvious. For example, if your company is frequently targeted by environmental activist groups for its use of packaging materials, you would want to select one of the more influential, yet reasonable, groups focused on packaging issues. The matrix provides a tool for your team to rank the various groups by their level of interest in topics that concern your company and their level of influence over those topics.

While some stakeholder groups are ideal candidates for your advisory panel, you should not lose focus on other organizations. For example, Greenpeace is highly influential on packaging issues but is more interested in a competitor than your company. In this case, it makes sense to put Greenpeace in the “keep satisfied” quadrant to avoid becoming its next target. Engagement with the stakeholders in this category could include holding a regular dialogue with them to understand their issues and report on your progress on these issues. Since Greenpeace is focused on preserving the rainforest, your dialogue should focus on your company’s policies and programs to eliminate packaging made from rainforest materials.

For the stakeholders that are not as influential as Greenpeace, but have demonstrated genuine interest in your company’s CR programs, it is beneficial to keep them informed and listen to their input. For example, the neighborhood association near one of your company’s facilities has repeatedly contacted company management about noise issues. While this group’s narrow interests and low influence would not make them a great candidate for a standing advisory panel, it is still very important to have an active dialogue with stakeholders that are interested in your company. Ignoring these groups risks alienating them, which could lead to protests, or worse. By engaging with interested groups you can not only avoid alienation, but also create ambassadors for your company.

In addition to this initial sorting of stakeholder interest and influence on key topics, your team should assess the posture of stakeholders toward company engagement. While some stakeholder groups are interested and influential, they might be poor candidates for an advisory panel. For example, groups that are established to campaign against companies, such as Greenpeace, are not likely to affiliate themselves with a company advisory panel, nor would their participation be all that useful in this context. These groups are far more comfortable working from a distance so that they can maintain their independence and highlight alleged company misdeeds in the press.

Other factors to consider when selecting stakeholders include:

• Issue relevance. Does the stakeholder focus on the issues relevant to your company?

• Willingness to engage. Does the stakeholder have the experience, time, and inclination to engage with your company?

• Influence. Does this stakeholder reach a broader audience? This factor is often the critical decision point

• Innovation. What is the stakeholder’s track record for creating new approaches or contributing to partnerships?

• Location. Is the stakeholder focused in the geographic areas of importance to your company?

Define the issues for engagement

Start the process by defining the key issues for review and discussion. These issues should be important for your company and for the stakeholders on the panel. Make sure that these are issues for which you truly want and can use feedback. For example, at the time of this writing, AMD recently established a new set of material issues and is working on the development of strategies for them. Working with Ceres, AMD is establishing a stakeholder panel to review this work and advise us on these strategies as well as ways that AMD might measure and improve its overall corporate responsibility performance.

Establish governance and ground rules

In the Project XL example above, Intel used a very structured governance process that was appropriate for that project. Typically, the rules of engagement will not have to be as defined or rigid as this example. In most cases, the sponsoring company is seeking advice and it is clear to all involved that the ultimate decision for acting on the advice remains with it. Even so, it is useful to define the purpose, scope, and objectives of your panel in a charter document. This document should outline the following elements:

• Purpose and scope. This section of the charter document outlines the scope of the engagement with the panel. For example: the panel will focus on advising the company about corporate responsibility strategies. It should also state that the panel serves as an advisory body and the company is under no obligation to act on advice from the panel (again, it is best if you demonstrably take actions based on the panel advice, but this provision in your charter can help align expectations). You should also include language in this section of the charter that makes it clear that no confidential information will be shared with the panel to avoid any implication that this is a group of “insiders” (this is especially important if your panel includes investors)

• Governance. Typically, the panel will operate by consensus. When the panel is established as an advisory group, a governance provision is somewhat unnecessary since all opinions are welcome. If the panel will have some decision-making authority, it is essential to establish the ground rules for reaching a decision (e.g., consensus, simple majority, group majority, group consensus, etc.) in this section

• Confidentiality. This section sets out how the identities and opinions of the stakeholders will be shared beyond the panel’s operations. In most cases, panels operate by the Chatham House Rule, which states: “Participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.” There may be cases where you and/or your stakeholders want to reveal information from the panel – for example, if you chose to publish panel opinions in your corporate responsibility report. In these cases, obtain all panelists’ consent to disclose in writing before proceeding

• Funding. It is important to define the extent of financial support that your company will provide to stakeholders for their participation. Financial support is negotiable, but is typically provided for the nonprofit participants for items such as travel costs and independent technical assistance

• Facilitation. Make it clear that a third-party facilitator will be utilized to manage the panel operations at the cost of the sponsoring company

• Terms of membership. This section sets out the length of engagement and the expectations for the number and duration of meetings as well as any deliverables. This section should also outline a code of conduct that members are expected to follow and the process for releasing a member from the panel. For example, a member could be released if they violated the confidentiality terms

Informal stakeholder engagement

There is a range of ways to get input from stakeholders that are less formal than creating a standing stakeholder panel. Although these methods are less formal, it still makes sense to go through a stakeholder mapping exercise to identify the people and groups that you want to contact. The main difference between formal and informal engagement is the depth of the commitment. In the formal stakeholder panel the participants have made a long-term commitment to the company and issues. Informal consultations have no such commitment. The advantage of informal stakeholder engagement is that you can get feedback quickly and easily from a broad sample of people and/or groups. The disadvantage is that the feedback may not be as well informed and you won’t necessarily have the time to build the relationships and trust that come from a formal panel.

Below are some proven methods to engage with stakeholders short of setting up an informal panel:

Exercise your network

Look over your network of contacts and conduct a quick stakeholder mapping exercise. Select a few influential people and set up phone calls or one-on-one meetings to cover the issues in your program and obtain feedback. A good practice is to draft an interview guide and background document ahead of time and share it with the people you will call. Also, you should think through what you might offer them for their time. For example, if the results from interviews might be of interest to them, you should offer to share a summary.

Online forums

In the Internet age, it is almost impossible to avoid a continuous dialogue with a wide variety of stakeholders though social media. Just by monitoring and responding to the comments on your blog feed, Twitter, and Facebook accounts, you will get a sense of stakeholder opinions. You may also have a “contact us” feature on your CR website and report that will garner some stakeholder feedback (in my experience, however, this format generates more solicitations than real feedback). You can also develop more focused online forums to solicit feedback by setting up challenges, prizes, or contests on your website, Facebook page, or other external site. One of the more innovative examples of online stakeholder feedback is from SAP. The company published its CR materiality matrix on its website in a format that allowed users to move the issues between the quadrants on the matrix.71 Its system records the selections by each person who interacts with the site.

Third-party research

This method engages a third party as a go-between for the company and the stakeholders. This allows the stakeholders to be more forthcoming with opinions. Depending on the situation, you can set up these interviews to allow the stakeholders and/or the company identity to remain anonymous.

Focus groups

These are similar to the formal stakeholder panel model discussed above with one important difference: the stakeholders have no continuing obligation after the meeting. Focus groups are typically issue-specific meetings where your facilitator is collecting opinions on an issue from a diverse group. It is wise to go through all of the steps you would in setting up a standing stakeholder panel – defining the scope of engagement, selecting participants, establishing ground rules, and selecting a facilitator – but within a more narrowly defined scope and schedule.

Engagement with socially responsible investors (SRI)

Socially responsible investors are a distinct category of stakeholders for your company’s CR programs. The SRI community is a diverse mix of investment fund managers and analysts who are, in general, very sophisticated in their level of understanding of both your company’s business model and your CR strategy. To understand how to work effectively within the SRI community, it is helpful to divide it into two categories: SRI analysts and SRI funds.

SRI analysts

These are the firms that collect and analyze your company’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) data and provide the results to investors. Sustainable Asset Management (SAM), Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), Trucost, Sustainalytics, and IW Financial are some of better-known entities providing this service. While there has been consolidation in this field, there are still many SRI analyst firms that gather data for the investment community.72

ESG analyst firms also sell their research to provide the data for company rankings such as Newsweek magazine’s “Green Rankings” and Corporate Responsibility Officer Magazine’s “100 Best Corporate Citizens” list. Each of these rankings utilizes a different and sometimes proprietary method for ranking company performance. The “Rate the Raters” study by the consulting firm SustainAbility does a nice job of exploring the world of corporate responsibility rankings and ratings.73

The important thing to understand is that each of these analyst firms uses a different and often proprietary screening method to evaluate your company. For example, one analyst may weigh water conservation more heavily than carbon management while another may put labor issues in the forefront. The bottom line is that there is no harmonized way to measure corporate sustainability, so each firm does it in its own way.

SRI funds

The number of investment funds that apply a social/environmental screen to company stocks is growing rapidly. The 2010 Social Investment Forum report states that there are now 493 SRI funds, which is more than double the 201 SRI funds that existed in 2005. Some of these funds have been around for quite a long time, such as Calvert Investments (founded in 1976) and Trillium Asset Management (founded in 1982), but new SRI funds are popping up all the time. Also, many of the large public employee retirement funds such as TIAA-CREF and CalPERS use some form of ESG screening for a portion of the funds they manage.

From my experience, there is little consistency in how SRI funds screen companies on ESG issues. They may buy research from one or more of the analyst firms or use their own screening methods or some hybrid. Many of these funds also have blanket prohibitions against buying stock in certain firms depending on their business. For example, many of the religiously based investment funds will avoid companies involved in tobacco, alcohol, or weapons.

It is likely that members of the SRI community will be participants in the various forms of stakeholder engagement discussed above, but because the SRI community can influence your company’s stock, there are a few additional methods to interact with them discussed here.

The SRI world is complex. There are a myriad of socially screened mutual funds, ESG investment analysts, and responsibility ratings systems. For example, the 493 U.S. investment funds in the Social Investment Forum report accounted for $569 billion in total net assets.74

Each SRI fund utilizes its own screening system to decide which companies it will include in its portfolio. As mentioned above, some funds simply screen out companies involved in alcohol, tobacco, or weapons. Other funds have their own in-house analysts that screen investments based on their investors’ social or environmental priorities, or use the research from ESG analysts described above to select stocks.

If you get the impression that working with the SRI world is complex and time-consuming, you are correct. However, there are huge benefits that you can achieve for your company by engaging with this stakeholder group. The primary benefits are:

Increased investment

The Social Investment Forum estimates that, as of 2010, the total professionally managed assets following SRI strategies amounts to $3.07 trillion and is growing at a faster pace than conventional investment assets. This report estimates that SRI assets grew at 380% from 1995 to 2010, while conventionally managed assets grew 260% during this same period. In addition, SRI investments grew during the 2008–2009 financial crisis while conventionally managed assets remained flat.75 Based on these trends, some corporate investor relations departments have identified SRI funds and analysts as important stakeholders.

Lower volatility

SRI-managed funds are dominated by large institutional investors such as state or city employee retirement funds. These groups tend to be value investors rather than market-timers that move in and out of stocks quickly. These are the types of investor that appeal most to your investor relations department because they hold stock for a longer period of time and can lower the volatility of your company’s shares.

For many years now the SRI community has collaborated on developing and filing shareholder resolutions on ESG issues. If your company is publicly traded in the U.S., any shareholder with $2,000 worth of stock can file a resolution. The resolutions can be on almost any matter involving the company and, with few exceptions, must be included on the overall “proxy ballot” (where all shareholders get to vote on the resolution – one vote for every share they own). Decades ago, social activists discovered the shareholder resolution process as a way to raise awareness within companies on a wide variety of issues. Often, the SRI community will develop several standard resolutions that are filed by shareholders of targeted companies. For example, in 2011, a series of resolutions were filed that asked companies to assess their human rights policies in countries outside the U.S. where their business operations are hosted.

The Social Investment Forum Foundation reported that more than 200 institutions filed ESG shareholder proposals between 2009 and 2010.76 Typically these proposals ask the shareholder to vote on an ESG issue that the filers would like to see the company address. For example, Apple received a filing that sought to require the company to issue a public sustainability report (as opposed to the report Apple issued solely on supplier responsibility).

Each year, the number of these shareholder resolutions increases and the number of votes they attract increases as well. By working collaboratively with the SRI community you will be in a better position to understand which issues are likely to be included in shareholder resolutions and possibly avoid a filing by proactively explaining your company’s performance on these issues.

ESG proxies, or shareholder resolutions, may demand that your company disclose its carbon emissions or endorse human rights principles. If you encounter an ESG proxy, you can often negotiate with the proxy filers (usually an institutional investor in your company) and, by explaining your programs or agreeing to take additional steps, you may be able to get the proxy withdrawn before it is added to the shareholder ballot. After negotiating on several ESG proxy issues at two companies, my experience is that working with the proxy filers is a far better process than putting the issue to a shareholder vote. While the company will usually win the vote, the ballot will have to include the issue and your company’s voting recommendations – all of which have to run through a lengthy review process and can be controversial. By engaging in an open dialogue with the filers, you can build trust and mutual understanding. It is likely that you are working on the same issues in the filing and, with some internal negotiations, may be able to rearrange priorities and satisfy their concerns.

The SRI ‘road show’

Investor road shows – where your company’s executives travel to meet with a number of influential investors and analysts – have been a common practice in the investment world for some time. This format has also become an annual or semi-annual event for many corporate responsibility leaders. The SRI road show is simply a series of meetings with SRI fund managers and analysts, the purpose of which is to tell your CR story and hear their feedback. Your investor relations (IR) department, in conjunction with your CR team, usually sets up these meetings and agrees on the speakers and the key messages. Over the course of a few days, a team from IR and CR will meet with several fund managers and analysts in their offices – in the U.S. this means going to Boston, New York, and Washington, DC. Your company might also cover the SRI firms in the European market. The Asian SRI community is still in an early stage, but growing rapidly.

On my last SRI road show, we conducted nine meetings in two days with most of them scheduled back-to-back. The typical presentation starts with an overview of company financials, strategy, and outlook from the IR department representative. The back half of the presentation is focused on the corporate responsibility story. In my experience, the SRI community is completely focused on the CR section of the presentation. If you are ever on one of these road shows, expect that you will be on center stage.

The structure of the CR portion of the presentation should cover the background for your program, strategy, goals, performance indicators, and any hot topics. For example, during AMD’s last SRI road show we spent a substantial amount of time discussing a relatively new and sensitive issue: conflict minerals. This issue refers to the use of minerals originating from conflict areas in Central Africa. The profits from mining and trading in these minerals have funded armed groups responsible for mass killings and rapes in the region.77

Whether your role is to present the CR story or if you are helping to develop the content for these meetings, it is best to set a schedule in advance to go over the presentation and hold a dry-run session with the team. In your dry-run session, assign someone to play the role of the investors and analysts and ask hard questions about the issues in your presentation and other issues that you may not anticipate. Remember, this is a sophisticated audience with years of experience reviewing corporate responsibility programs. Also, make sure to build in time for feedback. Given the SRI community’s level of knowledge, their feedback can be extremely valuable for your program. By having an interactive discussion, you will build relationships with these important stakeholders.

The SRI community has formed an association known as SIRAN (the Social Investment Research Analysts Network). By connecting with SIRAN, your company can efficiently cover many of the SRI analysts with one meeting or conference call. Conducting group meetings with a variety of SRI representatives can be efficient, but it may not be sufficient for your company’s needs. One-on-one meetings with SRI fund managers who are tracking your company are still the best way to have an in-depth dialogue. These one-on-one meetings will not only help solidify the relationship, but they also tend to allow for a more open exchange and a deeper dive into issues. In addition, the SRI funds and analyst groups all look at CR data in different ways. For example, some funds may focus on water usage statistics while others look primarily at labor issues in the supply chain. By meeting with a select group of fund managers and analysts you can build an understanding of their top issues, and hopefully address them at the meeting and follow-up.

Conclusion

At its essence, corporate responsibility is about integrating social and environmental concerns into corporate decision-making. To do this effectively, you need to understand the views of influential stakeholders external to your company who are well versed in these topics. While there are many ways to engage stakeholders and gain their perspectives, all leading corporate responsibility programs include some form of stakeholder engagement. Regardless of the format that works for your company, this is an essential element to building a credible program. Use the tips and experiences in this chapter to create a stakeholder engagement process that is customized to your company’s culture and circumstances.