8

Discourse Regarding China: Cyberspace and Cybersecurity

The significant position acquired, in recent years, by discourse analysis in studies conducted in international relations is, to a large extent, attributable to the success of the constructivist paradigm (Nicolas G. Onuf1, Alexander Wendt2, Thomas Lindemann3), and notably to the techniques of the Copenhagen School (security theories).4

Discourse is not a way of learning something about a reality, but rather a way of producing reality, rendering something a reality.5 The basic premise of discourse theory runs that the way in which we think and say things reflects the way in which we act in relation to the object of that discourse.6 Thus, according to this view, there exists no real world untouched by our thoughts, our ideas, and it would be useless to try to distinguish fixed political and social structures, a static reality, independently of our own interpretation of it.7

This theory also postulates that language is a form of social power. The social implications of discourse lie in its power to influence, its persuasive nature, its capacity to alter ideas, beliefs and behaviors.8 Discourse is a social practice which produces the effects of power, i.e. which is aimed at dominating other people.9

Discourse analysis, which is a relatively recent method in the field of international relations10, is commonly used to reveal the established relations between discourse and political practice11, in order to understand the way in which the textual and social processes are connected, and what the implications of those connections are12: how and why the political conditions behind the discourse arise13; to reveal the intentions inherent in the discourse14; to identify the discursive strategies employed to legitimize15 political actions (consensus- or consent-seeking; discourse in the service of a particular ideology; etc.).16

In this chapter, we examine the changes in the way in which China is viewed (representations, perceptions), by way of analysis of the discourse on the subject of China and its relation with the issues of cyberspace, Cybersecurity and cyberdefense strategies.

The corpora upon which this analysis is founded are as follows:

– for our first section, aimed at identifying the main themes in discourse and research about China (cyberspace, Cybersecurity), we use a very large corpus comprising essentially academic work and resources available on the Internet. We have limited the scope of our observation to resources in English and French;

– for the second section, where the goal is to study the arguments of discourse circulating within the American institutions of power, we draw upon three sources: the annual reports submitted by the Department of Defense to the United States Congress; the projections published by the National Intelligence Council; and the discourse of the successive US Secretaries of Defense. These sources enable us to cover a sufficiently long period of time (DoD annual reports are available for 2002 onwards; the NIC reports for 1997 onwards; and the speeches made by the Secretaries of Defense, online archives begin in 1995), offer the advantage of being available online in their entirety, and reflect the viewpoints of the people in power: the political and military decision-makers, and influential personalities.

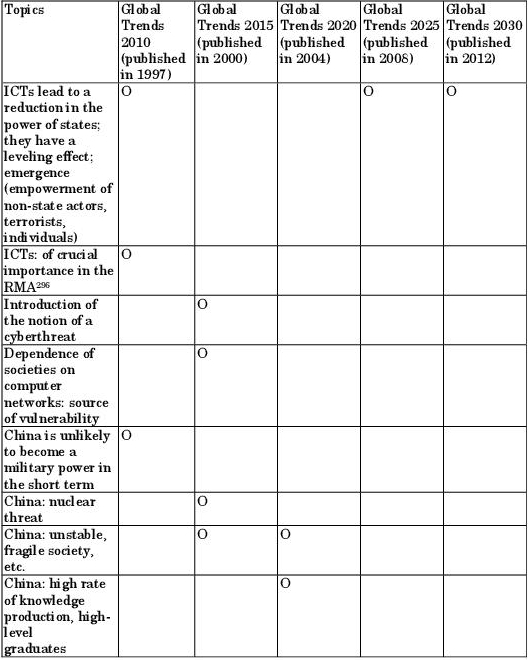

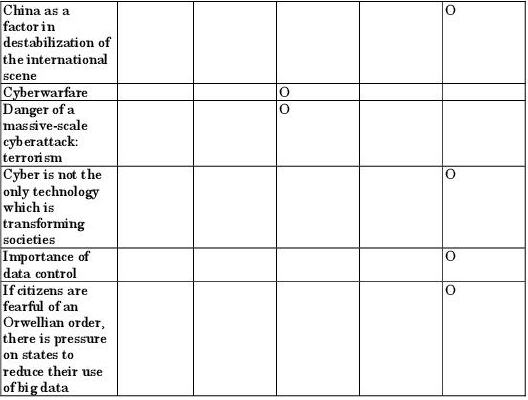

To illustrate this discourse, we give many long verbatim quotes, but also show summaries in table form so as to clearly reveal the evolution in terms of themes. The aim is to demonstrate the variables of the available discourses, the relationships between them, and the evolution of those discourses, over the past two decades. This initial analysis could, undoubtedly, later be supplemented by work on the evolution of the discourse conveyed through the media, but also in industrial environments. Finally, an additional project could address the more complex task of reconstructing the path of various ideas (where they first surface; what paths they follow as they are diffused; who has the power to influence). In this chapter, we limit this study of the evolution of ideas to identifying the scenarios which have emerged over the past 20 years.

8.1. Identification of prevailing themes

By way of a state of the art on the work conducted on the subject of China – particularly its relationship to cyberspace – we can see that the discourse on China is organized around relatively few themes, types of discourse, arguments, viewpoints.

8.1.1. Depictions of the Internet in China

Many research projects have been conducted on the topic of China’s Internet from a historical point of view (when it came about, how its industries have developed, who the designers of the Chinese Net are), from a statistical standpoint (number of users, evolution of uses), but also from a cartographic perspective (how the networks are organized, how the users and data flows are distributed geographically, etc.).17

The sources which can be consulted are many and diverse. Since the late 1990s, such reports have been being published by the Chinese government (White Paper on the Internet in China)18, the CNNIC (Statistical Report in the Internet Development in China)19, with regular statistical reports20 on the evolution of the Internet in the country being published.21 Many international websites give statistical data on the Chinese Internet.22 Studies are also regularly being produced by researchers, describing China’s Internet both from a technical and a general point of view (Liu Dong, 200523; Jane Lael, 200524; Z. Shi, Z. Guo, 200725; Burson-Marsteller, 201126); examining the roles of the actors involved in the Internet (Qiheng Hu, 200727; Zhang Guanqun, Wang Hui, Yang Jiahai, 200928), and the distribution of users (L. He, L. Gui, Q. Le, 200429; Guo Liang, 200530; Guo Liang, 200731).

These studies are joined by analyses which focus more specifically on the development of technologies in China:

– the history and evolution of the ICT industry in China (Zhu Gaofeng 200532; Nir Kshetri, 200933; Jiang Zemin, 201034; Xiangning Wu, 201035; George I. Askew, 201036; Guobin Yang, 201237; Michael Pecht, Weifeng Liu38; EU Report, 201339)

– the impact of China’s industrial development on the level of competitiveness of other states, both on a regional level (Zhu W. 200140; Ted Tschang, 200341; Xiangning Wu, 201042) and worldwide, notably analyzing the role of companies such as Huawei, ZTE, Lenovo (Report of the US Congress, 201243; Lucas Solorio, 201444);

– market access conditions applicable to the Chinese Internet (Peter K. Yu, 200145; WilmerHale report, 200646; etc.);

– regulation of industry (Lijun Cao, 200747). transform China, on the international stage48, but also internally (Z. Jonathan; W. Enhai, 200549)? What are the instruments (political, legal, etc.) and who are the actors involved in the regulation of the Chinese Internet (Mayer Brown, 201250)? Does the Internet have a levelling role in Chinese society (Scott J. Shackelford, 201451)?

8.1.2. Impact of cyberspace on Chinese society

Beyond descriptive, cartographic or statistical (etc.) approaches, the analyses in the existing body of literature focus, in particular, on the social, political, economic and legal transformations caused by the introduction of networking in China: for instance, civilian capability of expression, State surveillance and control of the populace, use of social networks, etc.; to what extent can cyberspace

The political nature of the Internet is noteworthy. Thus, a very great many publications examine the question of the democratization of societies thanks to the new powers granted to individuals by cyberspace (a space for expression, for circumventing censorship, for challenging), and the tension between (cyber) surveillance and sousveillance.

Thus, many works look at the question of democratization, organization of dissidence, the strategies of the Internet users to circumvent the State’s surveillance52, and those of the governments to control the Internet (Philip Sohmen, 200153; Jason P. Abbott, 200154; Michael S. Chase, James Mulvenon, 200255; Christopher R. Hughes, 200256; Chin-fu Hung, 200357, 200558, 201059; OpenNet Initiative reports, 200460; Wei Qi, 200561; Gary D. Rawnsley, 200662; Chunzhi Wang, Benjamin Bates, 200863; Xiaoru Wang, 200964; Ashley Esarey, Xiao Qiang, 201165; Séverine Arsène, 201266; Yiyi Lu, 201367; Jiao Bei, 201368; Loubna Skalli-Hanna, 201369]. The question of censorship and cyber surveillance, which is directly linked to the questions about the democratization of societies, is a crucial one (Jonathan Zittrain, Benjamin Edelman, 200370; James A. Lewis, 200671; Rebecca Mackinnon, 200872; Xiaoru Wang, 200973; Shishir Nagaraja, 200974; RSF report75; Xueyang Xu, Z. Morley Mao and J. Alex Halderman, 201176; Emilie Frenkiel, 201377). Researchers are also posing questions about the reconfiguration of national identities in the Network Age, and the manifestations of nationalism (S. Zhao, 199878; Christopher R. Hughes, 200079; Yu Huang, 200280; Françoise Mengin, 200481; Z. Wang, 200882; etc.), which is a potential source of insecurity for other states.83

The role of the social media is also essential in these analyses (Louis Yu, 201184; US Congress report, 201185; Edward Tse, Adam Xu, Andrew Cainey, 201286; KPMG report, 2013).87 The hypothesis usually formulated is that of the empowerment of the citizens, for whom the networks represent a forum to express themselves, where there is a relatively reduced degree of control by the authorities over free expression, the capacity to impose a political agenda (Haiqing Yu, 200488; Rebecca Mackinnon, 201089; Qin Guo, 201190; Gary King, Jennifer Pan, Margaret E. Roberts, 201391). The evolution of the Internet in China, its uses, its construction, reflect a “dynamic, changing Chinese society”.92 This upheaval is desired and supported by the State, which has invested heavily in the development of infrastructures, and encourages the development of the information society. In China, like everywhere else, the Web benefits everybody, although it does also expose everybody to new risks: greater openness, fuller communication, more abundant exchanges, freer expression, and greater capacity to watch and control. The revolution in ICTs does not directly lead to democracy. However, it does have political consequences. It impacts on societies’ development: the rise in power of the middle classes (who account for the majority of the population of Internet users), the desire for modernization, patriotism, social mobilization, disputes, etc.

It should be pointed out that a number of Chinese authors, or of Chinese descent, have discussed this socio-political aspect of the Internet (Tai Zixue 200693; Zhou Yongming, 200694; Xu Wu 200795; Yongnian Zheng 200796; Rebecca Fannin 200897; Sherman So and J. Christopher Westland 200998; Tiebing Xu, 200999; Hong Xue, 2010100; Yun Zhao2011101; Wang Jun 2011102; Guobin Yang 2011103; Rodney Wai-chi Chu, Leopoldina Fortunati, Pui-Lam Law, Shanhua Yang, 2012104; Guosong Shao, 2012105). cyberdefense are even often defined as being indicative of China’s true ambitions on the international stage.

8.1.3. The Chinese cyber threat

The “Chinese cyber threat” plays an important part in the considerations about China’s evolution and the relations it can have with the rest of the world.106 China’s practices in cyberspace, its policies and strategies for Cybersecurity and

Also, many observers view the cyber threat as being only one facet of the threat constituted by China, which is engaged in a processof growth, but whose unpredictable evolution presents cause for concern.

These issues (cyber threat, Cybersecurity, cyberdefense, cyber-policy and strategies) thus fit into the more global discourse about the Chinese threat. They are the topic of specific publications, which emerged in the United States in the 1990sand have since been widely disseminated the world over.

The topic of cyber threat is jointed around a number of variables:

The discourse about international insecurity, rooted in the worrying evolution of Chinese State- and non-State capacities and practices in cyberspace, dates from the end of the 1990s and the start of the 2000s (T. Yoshihara, 2001115; Peter Hays Gries116, whose study relates to the expression of Chinese nationalism following the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in 1999). Since then, a copious body of literature has been produced on this subject, and the overview given here is not, by any stretch of the imagination, intended to be exhaustive. Let us simply cite the works of John Tkacik, 2008117; Jayadeva Ranade, 2010118; Derek Scissors, Steven Bucci, 2012.119

In the discourse in the media worldwide about Cybersecurity, the Chinese hacker has become an imposing and unavoidable figure. However, s/he is absent from the academic reference works on the sociology of hackers from the late 1990s120, or even more recent works121, on the psychology of hackers.122 China is believed to be targeting cyber-attacks in all directions, without imposing any limitations at all on that activity (testing what it is possible to do, and attacking anything and everything that is exposed).123 Chinese hacking could have a significant impact on trade law and human rights.124 The phenomenon is so widespread that 2008 could, in fact, be dubbed the “Year of the Chinese hacker”.125

The literature about Chinese hackers mentions:

– non-State-sanctioned cyber-espionage126;

– the significance of cybercrime (Michael Yip127; Zhuge Jianwei, Gu Liang, and DuanHaixin128; Aidong Xu, Yan Gong, Yongquan Wang, Nayan Ai129), as a phenomenon in juvenile crimes130; in international relations (Lennon Yao-Chung Chang writes about the prevention of cybercrime, specifically in the context of the relations between continental China and Taiwan131), or indeed the threat to the West (David Hanel, 2013132); certain authors attribute the dynamism of this threat to the permissive attitude of the Chinese State;

– military-based operations (intelligence units133 stealing intellectual property on a worldwide scale134);

– the intervention of patriotic/nationalistic hackers, hacktivists (hackers whose motives are political), who have been besieging the networks for nearly 20 years, and whose practices are specifically examined in works such as those of Michael Yip and Craig Webber, who call them “cyber-warriors” 135; Alexandra Samuel136, who compares them to cyber activists, one of whose main objectives is to circumvent the State’s cyber control mechanisms; and Sheo Nandan Pandey137, who seeks to identify the Chinese characteristics of this hacktivism.

Figure 8.1. Hacktivism: defacement of a Website, signed by the group Honker Union of China. The content of the slogan displays the desire to defend the interests of the Chinese nation138

Figure 8.2. Screenshot of the Webiste http://www.ssol.com/ defaced by China Honkers139

8.1.4. The Chinese army: its practices, capabilities and strategies

The Chinese army, its strategies, its developments in terms of capacity, its manifest interest in information warfare, mastery of information space (and cyberspace), and the increasing use of computerization in the forces (or more specifically the notion of informationization, which covers the computerization of weapons systems but also the integration of operations in cyberspace), modernization of the forces as part of the revolution in military affairs140, are the focus of a not-insignificant portion of literary production, mainly in the form of official reports produced by or for the American administration.

These works may relate to the impact of China’s cyber-policies on international relations.

Amongst the numerous English-language publications on these subjects, we can cite the most significant as being: the work of James Mulvenon (1999)141, Toshi Yoshihara (2001)142, Nina Hachigan (2001)143, Timothy L. Thomas (2001144, 2004145, 2006146, 2007147, 2009148), Ken Dunham and Jim Melnick (2006)149, Brian Mazanec (2008)150, Kevin Coleman (2008)151, Ron Deibert and Rafal Rohozinski (2009)152, Bryan Krekel and George Bakos153, Jeffrey Carr (2009)154, Gurmeet Kanwal (2009)155, R. A. Clarke and R. Knake (2010)156, Elisabette M. Marvel (2010)157, Martin Libicki (2011)158, Dmitri Alperovitch (2011)159, Venusto Abellera (2011)160, C. Paschal Eze (2011)161, Mark A. Stokes, Jenny Lin and L.C. Russell Hsiao (2011)162, Li Yan (2012)163, William T. Hagestad (2012)164, Dennis F. Poindexter (2013), Larry M. Wortzel (2014).165

It would be remiss to neglect to mention the official reports painting China as a potential threat because of the development of its military capabilities. In seeking to uncover the view of the Americans, we can exploit the following resources:

– a report from the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives177, including China in a specific group of actors posing a cyber threat (China, Russia and Iran).

Reports from Cybersecurity companies contribute to this discourse about the actions of the Chinese army in cyberspace. The report most recently released in the media was produced by the American company Mandiant, in 2013.

8.1.5. Espionage

The question of cyber-espionage, which is an issue of strategic importance178, is cross-cutting, and therefore is included in works on cybercrime, cyber-attacks and State practices.

Whilst it clearly offers an advantage to infiltrate the computer systems of major enterprises, State services, armed forces, etc., the same actions directed at more modest actors raise questions: “Google Inc. (GOOG) and Intel Corp. (INTC) were logical targets for China-based hackers, given the solid-gold intellectual property data stored in their computers. An attack by cyber spies on iBahn, a provider of Internet services to hotels, takes some explaining […] The hackers’ interest in companies as small as Salt Lake City-based iBahn illustrates the breadth of China’s spying against firms in the U.S. and elsewhere. […] “They are stealing everything that isn’t bolted down, and it’s getting exponentially worse,” said Representative Mike Rogers, a Michigan Republican who is chairman of the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence”.179 This “no-holds-barred” strike is perhaps attributable to the voracious appetite of China, which is determined to make up lost ground (in terms of knowledge, technologies, all kinds of expertise) and, as quickly as possible, turn itself into a competitor or a credible alternative to American power. Scott Borg, Director of the US Cyber Consequences Unit, denounced what he believes “…may be the biggest transfer of wealth in a short period of time that the world has ever seen.”180

According to the US authorities, it is in this respect that Chinese espionage is radically different from that of the United States: the American cyber spies target the secrets of foreign governments, military secrets, and fight against terrorism. American cyber-espionage, it seems, is acceptable because it fits into the context of an acceptable norm – that of the power game on the international scene – and is only for defensive purposes (to protect the country against future threats). Chinese espionage goes beyond the bounds of the norm, attacking illegitimate targets, and having offensive objectives. With this discourse, the United States refuses to assume the role of the villain, which they place on the shoulders of China, Russia and Iran.

The threat constituted by Chinese cyber-espionage is apparently different from the cybercrime which takes place in the rest of the world. It is held to be a major threat, as “China’s economic espionage activities against the United States are greater than the economic espionage activities are of all other countries combined.”181 Many official reports are devoted to defining that threat.182

However, the author of that assessment, who feels the need to avoid any exaggerated statements (“Many discussions of Cybersecurity invariably involve exaggeration. The source of this exaggeration is often a lack of specificity in precisely assessing intent, capabilities, and effect”), tempers his judgment: “The effect, however, is not one of clear-cut benefit to China. The strategic implications of this theft are difficult to assess. Some call it the greatest transfer of wealth in history; others call it a rounding error for an economy as big as that of the U.S. Neither characterization is correct”. However, China’s espionage activities are singled out: “What is unacceptable is espionage for purely commercial purposes […] Where China’s espionage efforts differ significantly from international practice is in the rampant economic espionage carried out by Chinese government entities, including the PLA”.

Hence, returning to the example of the attack on Google a few years ago (2009-2010), James Lewis defines the acceptable limit: provided China’s intelligence services are attacking systems for subjects in the areas of security and national defense, it is acceptable; when those same espionage operations are used to steal industrial secrets, it becomes scandalous. The disagreement between China and the rest of the world appears to lie in this difference of opinion, the lack of sharing of international norms that are tacitly accepted by the actors within this international community.

Other stances seem to demonstrate China’s incompatibility with the “norms” of the international community: at the ITU conference, China proposed rules which were different to those accepted by the West. It marginalizes itself by way of its practices, its choices, its way of acting and thinking. Yet the problem of the background discord does not only involve China, because from the Western point of view, there are many states which do not conform to the norm, and the motives are numerous, especially in terms of respecting the fundamental values defined by the West as universal standards.

The West’s position, or at least that of the United States, seems firmly rooted. The solution proposed by James Lewis in his discussion of how to deal with the issue of Chinese cyber-espionage is essentially to attempt to change China’s behavior. In Lewis’ eyes, China’s “economic espionage provides a technology boost, but puts bilateral relations with the U.S. at risk and hampers China’s ability to create indigenous innovation”.183 There are significant limitations on the pressure which the USA can exert on China: “This is not a new Cold War. We cannot have a Cold War with one of our largest trade partners”.184

Published in February 2013, the report APT1: Exposing One of China’s Cyber-espionage Units185 claims to provide proof of the existence of Chinese military groups specializing in cyber-espionage operations, specifically targeting the United States. The survey, which examines 150 incidents observed over a period of 7 years, was able to reconstruct the profile of Unit 61398, attached to the 2nd bureau of the PLA, 3rd Department, located near to Shanghai. Besides this group, the authors of the report also claim to be observing dozens of others distributed throughout the world – around twenty of them in China.

All of the literature produced about Chinese cyberwarfare and information warfare capabilities has, since the 1990s, been painting the picture of an aggressive, fearsome nation, possessed of inexhaustible capacities (because when it is not a question of the threats represented by State actors themselves, it is a question of cybercriminals or indeed millions of citizens turned nationalistic hackers, constituting as many threats for the rest of the planet, in view of their skills and their motives); a nation whose defense strategies are unclear186, whose current approach of attacks carried out in information space is rooted in secular warrior practice (Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Chairman Mao’s irregular warfare). This portrait is based on the existence of forces of techno-warriors set up during the Cold War187, and expresses China’s determination to establish itself as an alternative to America’s hegemonic power, thus upsetting the international order established at the end of the Cold War. Faced with this situation, America and the whole of the industrialized world is in a vulnerable and inferior position (R. Clarke188; Joel Brenner189) because of their dependency on cyberspace, the number of potential enemies and the motives held by those foes, and seems to have no option but to prepare for confrontation by trying to make up their lost ground in terms of capabilities, both defensive and offensive.190 An alarmist discourse, rooted in the predictions made during the 1990s of a Cyber Pearl Harbor and other forms of cybernetic chaos, has taken hold amongst the political classes (for example, the Republican US Senator Mike Rogers declares that the United States is losing the cyberwar against China).191

It should also be noted that the subject of the Chinese cyber threat is often discussed by military or ex-military personnel: Timothy L. Thomas192, Scott J. Henderson193, Rich Barger194, Mark. A. Stokes195 and William T. Hagestad196 are among these commentators.197 Because of the profile of a portion of its directors, we can also consider that the publications emanating from Mandiant also fit into this category. Indeed, before he set up the company in 2004, Kevin Mandia worked as part of the 7th Communications Group (Pentagon), as a Special Agent for AFOSI (U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations). Travis Reese and Dave Merkel, both members of the company’s board of directors, are also former members of AFOSI. Richard Bejtlich, another member of Mandiant’s board of directors, and founder of the Website Tao Security198, was an intelligence officer in the U.S. Air Force CERT, as well as the Air Force Information Warfare Center (AFIWC) and the Air Intelligence Agency (AIA).

The publication of the report comes as the American authorities are engaged in a policy of toughening their positions in relation to cyberdefense: the announcement of the enhanced powers granted to Cyber Command199, a speech from the US Secretary of Defense about the need to protect the nation from cyber-attacks200, President Obama’s Executive Order on Cybersecurity201, dialog at the highest level between the United States and China over the question of Cybersecurity202, and toughening of the legal framework relating to cyber-warfare.203

Finally, the report has a place in an unusual economic context, which is extremely favorable for the Cybersecurity market (Mandiant’s turnover for 2012, which is over 100 million USD, is up by 76% in comparison to the previous year).204 The initiative does little to hide the commercial strategy of the enterprise: “Meet the Company That’s Profiting from Chinese Hacking.”205 The conclusions advanced by the report therefore may not be as objective as may otherwise be thought, and may not reflect reality, but only one aspect of that reality, with the perspective having been chosen with commercial or political aims in mind. These remarks lead us to consider all of the criticisms which have been leveled at the report, and the lessons that can be drawn from those criticisms.

The criticisms have come from China, based on clearly-defined arguments. The spokesman for the Foreign Ministry points the finger at the way in which the United States constantly levels accusations at China, saying that this type of approach is not helpful in solving the problem of cybercrime; that only international cooperation in the fight against cybercrime should be envisaged; that China too is one of the most prevalent victims of cyber-attacks; that the United States is the no. 1 source of those attacks, according to IP analysis; that China’s legislation, which has been toughened in recent years, and Chinese policy, take a dim view of such practices; that on the international scene, China, along with Russia and a few other countries, has proposed a code of good conduct which has thus far been snubbed by the United States; and finally, the spokesman expresses surprise that it is technically possible to so precisely locate and attribute blame to the aggressors, as it is well known that they tend to carefully anonymize their operations.206

Other criticisms, however, have come from the United States207 – particularly from the expert, Jeffrey Carr, first picking up on the numerous errors with which the dossier is fraught, and then the unsatisfactory methodology used. Thus, he points out:

These criticisms cast doubt on the very quality of the document itself, the validity of its conclusions, and the impartiality of its authors.

Another criticism relates to the taking of undue risks. Revealing information about the investigative capacities used in the gathering of the data will inevitably lead the aggressors to alter their behavior, thereby (temporarily, at least) weakening the united states’ security.208 However, the company gives a certain amount of self-criticism in this regard, explaining the choice within the report itself: it was felt that the publication of the truth merited this risk.

Whilst it does not truly provide any new information209, and fails to prove the identity of the aggressors, the report does, in its own way, contribute to the alarmist discourse, conforms to the train of thought developed over more than 15 years: it stresses how dangerous the operations carried out by the Chinese intelligence unit are, confirms the existence of units of techno-warriors (high-tech spies much like those employed by America), and emphasizes the vulnerability of the American actors (by highlighting the number of recorded incidents and the relative ease with which the aggressors carry out their espionage operations). The “experts” belonging to the company channel the same fear mongering discourse, backed up by evidence. Of course (as is their trade), they propose solutions to defend against these threats.

The process of securitization210 involves first identifying the threat (China, and its actions in cyberspace); naming the referential objects (critical infrastructures, companies, stability of the nation-State, western civilization, democracy, liberalism, cyberspace); next comes securitization proper, which entails the finding of solutions (cyberdefense policies, increasing of defensive and offensive resources, tightening of surveillance and control regulations, and commercial solutions).

In this process, the Cybersecurity firm is one of the key actors, on the side of the State, capable not only of offering solutions to the problems identified (protecting against the threat) but also of identifying and describing the threat. Thus, it has a significant degree of responsibility in the process of threat definition. The report and the criticisms of it demonstrate, once again, that, in spite of the effects of declarations, it is always possible to call the results into question, and put forward other, equally-credible hypotheses. The problem of attribution remains to be solved. However, though it may use uncertain results and debatable conclusions as a starting point, the technique still has an important part to play in the definition of a threat and (re)construction of a reality, which may have an impact not only from a commercial point of view (opening up new markets for (in)security) but also from a political standpoint (influencing the world view of the political decision-makers).

In the United States, a few rare critical voices are beginning to be heard – some of them calling for greater objectivity and discernment in the analysis of the threats (J. Carr and the various commentators on his blog about the Mandiant report; Eric C. Anderson in his Sino phobic discourse analysis211); others for greater restraint in the expression of the stakes in Cybersecurity policies (Martin Libicki, decrying America’s warlike rhetoric, which runs the risk of triggering an uncontrollable escalation in international violence212). Yet we may also ask about how much counterweight can actually be carried by critical views and calls for caution, in the face of an alarmist discourse which is anchored in nearly two decades of propaganda painting the image of a major adversary.

8.1.6. China, cyberspace and international relations

China’s might and its management of cyberspace are invariably of great importance in its international relations.213 The emphasis in debates and analyses is placed on a few central topics.

China’s use of cyberspace as a tool of power (John Oakley, 2011214; Sérgio Tenreiro de Magalhães, 2009215): interpretation error, an improperly-controlled action with unforeseen consequences, could put the spark to the powder keg. The risk is of the escalation of force, and of violence.228

These debates focusing on cyber-issues fit in with the broader question of the conditions of the ratio of strength between the two powers (David C. Gompert, 2011229), of which cyber is, ultimately, only one aspect, but one which causes numerous genuine tensions between the two states. Besides, adding cyberwarfare to the list of points of discord between China and the United States is, undoubtedly, not the best way to achieve better entente between the two states.230

In this context, it is rare to hear voices which attempt to relativize the significance of this specific threat: “Despite the PLA’s interest in and preparations for cyber operations, and the importance of networks to military operations, open source evidence does not justify the conclusion that the PRC is a threat per se. Much of what has been classified as a cyberattack is not hostile at all and is actually clandestine spying and a form of intelligence gathering inside computer networks. Hackers, China’s internal security threat, are likely their first and foremost priority.”231

8.1.7. Particular points from the Western perspective

Westerners are not capable of understanding Chinese society.232 This idea is formulated not by the Chinese, but by Westerners themselves.

Westerners have difficulty in comprehending the complex nature of modern China, because it does not fit into any of the typical categories. Tzvetan Todorov233 summarizes this complexity in the following terms: “China no longer corresponds to the “ideal model” of a totalitarian regime. Rather, to outside observers, China appears to be a baroque hybrid of communist rhetoric, represessive centralized administration and a market economy which allows, or even favors (something which would have been inconceivable in the time of Soviet and Maoist communism) openness to the outside world and enrichment of individuals.” The published analyses often dwell on the differences.234

Without appropriate referential frameworks to aid comprehension, for example, Westerners cannot understand why a society which frequently rises up against injustices does not rise up against the governing regime at the same time; why that society speaks out against corruption and embezzlement, but continues to have faith in its leaders.

Indeed, if we Westerners do not understand, affirms Jean-Louis Rocca, it is because our analytical filter yields nothing but contradictions. We would first be convinced that a democratic market is the only envisage able prospect; yet the culturalist paradigm speaks of the existence of a “Chinese model”, a specific approach, a particular channel, which is entirely defined. From this point of view, there would only seem to be solutions “à la chinoise”, different from our own. Interpretations of China thus hesitate between these two paradigms: thus, in order to discuss China’s political evolution, we say that it does not conform to the single model which is becoming widely adopted on the international scene (democracy), but we also accept that the switch to democracy in China may first require a political modernity “à la chinoise”, a transition to democracy or another form of democracy.235 Hence, analyses of China are constrained by the two paradigms (conformity to the Western democratic model; and the culturalist model).

These two paradigms are also found in the discourse produced about Chinese cyber strategy:

– China is far removed from the democratic model (there is control and censorship of the Internet in China), but also more generally from usages in accordance with the rules set by the international community. By placing emphasis on the lack of respect for these international rules with regard to espionage, the United States paint a picture of China which is outside of the “norms” which are becoming those of the modern international scene. The Chinese themselves appear to place themselves outside of this system, beyond the governance of these rules: after all, they published “Unrestricted Warfare”, meaning the usage of all kinds of technological tools in all directions, in contravention of the norms of international deontological laws or rules? By the principle of this contrast between an innocent (Western) democracy and authoritarianism236, measures taken by China would be condemnable (censorship, cyber surveillance), whereas those taken by democracies would be legitimate (cyber surveillance is a necessity for the maintaining of peace in a democracy). Could it be that the arguments are exaggerated when it comes to China? Do we lose some of the necessary objectivity? If this is so, however, is the problem limited to discourse about China or is it more general in discourse about Cybersecurity? Does the discourse about the cyber threat represented by the Chinese hacker accurately reflect the reality, or is it exaggerated?

– in addition, analysts also emphasize the development of a specifically Chinese channel, and have no hesitation in drawing the connection between ancient Chinese philosophy and modern thought (e.g. viewing China’s cyberdefense strategies and doctrines as deriving directly from Sun Tzu’s strategy). Western authors even affirm that China, because of its culture, its way of thinking, its philosophy, and its tradition, might be better prepared for cyberconflict than other nations in the world. Culturalism appears to be a practical way of explaining the Chinese exceptionality, as that country’s culture has always been deemed different, “separate”.237 Yet that uniqueness is not only to be understood in a negative light. We can hold up the difference as a model from which it would be wise to draw inspiration (e.g. by first understanding and then transposing the seminal principles laid down by Sun Tzu to our own culture, our own strategy).

Thus, our referential framework oscillates between two limits whereby China is an outsider, a “different” actor. This fundamental postulate greatly constrains any analysis, and is visible in the discourse published about China; “cyber” issues, security and defense are no exception to this phenomenon.

8.2. The evolution of American discourse about China, Cybersecurity and cyberdefense

We can gain an insight into American discourse and its evolution by analyzing three corpora: the Defense Department’s annual reports, relating to the evolution of China’s defense; the speeches given by the US Secretaries of Defense; and the prospective exercises carried out by the National Intelligence Council and published every four years. This corpus is not a reflection of the whole of American thinking, which would of course also be reflected through other political discourse (White House communiqués, Congress, GAO reports, etc.), the media, research publications, or websites, blogs, social media in the broadest sense. However, we have chosen to limit our corpus to these three sources, because we believe they give a fairly accurate illustration of the discourse of the dominant actors, which are capable of influencing political decision-making. Finally, these corpora have been chosen because they are easy to access (available on the Internet in their entirety), and for the period which they cover (the past two decades), which serve our objective here, i.e. to demonstrate the main arguments in the discourse and the evolution of those arguments over time.

8.2.1. The annual reports of the US Defense Department

As stipulated by the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, Section 1202, Public Law 106-65, amended by Section 1246, “Annual Report on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China”, of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010, Public Law 111-84, the Defense Department annually delivers a report to Congress on the progression of Chinese military power. Two versions of this annual report are produced: one which is not classified, which is available online on the Defense Department’s Website; the other which is classified. The report must focus on four aspects of the development of Chinese defense: its technological, strategic, organizational and conceptual dimensions. Finally, the report must not merely give overviews and observations, but rather must convey a prospective vision, all from the viewpoint of US/China relations, and of cooperation on issues of security.

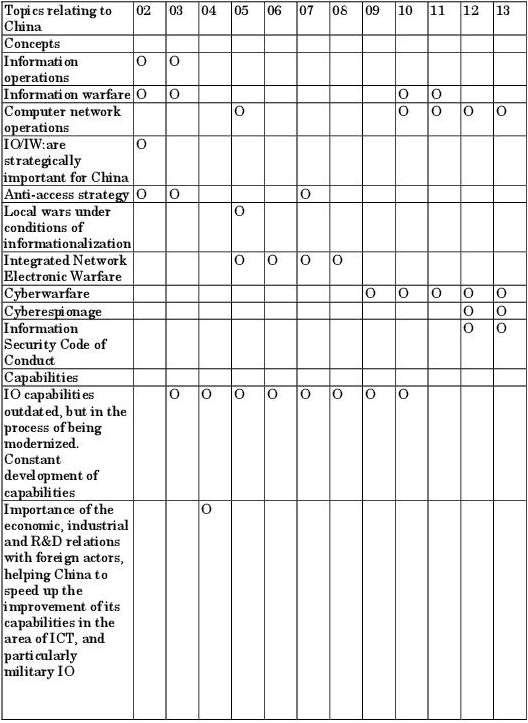

The first report published in 2002238 spoke of information operations and information warfare, and highlighted the strategic nature of those two concepts in Chinese defense policy: “China views information operations/information warfare (IO/IW) as a strategic weapon foruse outside of traditional operational boundaries”. Information space, which would later be called “cyberspace”, had a leveling effect: “China is particularly sensitive to the potential asymmetric applications IO/IW can have in any future conflict with a technologically superior adversary”. China was paying particular attention to IO and IW: “Both the Academy of Military Science and the National Defense University have published several books devoted, in part or completely, to this subject. These writings indicate a growing sophistication in the PLA’s understanding of all aspects of IO”. It was evident even at that point that China, like the United States, was integrating the use of ICT into military affairs: “China is pursuing IO/IW development as part of its overall military modernization. Combining information warfare--such as computer hacking--with irregular special and guerilla operations, would allow China to mount destructive attacks within the enemy’s own operations systems, while avoiding a major head-on confrontation”, with both an offensive and defensive objective: “Efforts have focused on increasing the PLA’s proficiency in defensive measures, most notably against the threat of computer viruses […] Increases in network defense likely will enhance China's understanding of virus propagation and behavior, creating a solid knowledge base not only for computer network defense (CND), but potentially also for computer network attack(CNA) through malicious software development”.

The report also highlighted China’s initiatives in terms of R&D in the domain, and the method of taskforce construction (in terms of human resources), based on using reserves of specialists – a method which would later be used by other countries: “In an effort to improve its skill base in the IT field, the PLA has been recruiting specialists via its reserve officer selection program”.

In spite of these efforts, the US felt that China did not yet have the means to penetrate the most heavily protected networks: “China has the capability to penetrate poorly protected U.S. computer systems”, but that did not take away from the potential danger it posed: China “potentially could use CNA to attack specific US civilian and military infrastructures”.

The development of nationalistic hacking added to the concerns created by the rise in power of China’s military capabilities, especially as the government could be supporting this kind of action: “In the near term, nationalistic hacking is likely to occur during periods of tension or crises. Chinese hacking activities likely would involve extensive web page defacements with themes sympathetic to China. Although the extent of Chinese government involvement would be difficult to ascertain, official statements concerning the leveraging of China’s growing presence on the Internet, and the application of the principles of “People’s War” in “net warfare”, suggest the government will have a stronger role in future nationalistic hacking”.

The 2003 report239 again deals with the same topics, but goes into greater depth. It again mentions the role of IO and IW in Chinese strategy, with these concepts notably encompassing “computer warfare, network warfare, temporal-spatial analysis, knowledge warfare, information protection, and electronic security”. The concept of IO is therefore a complex construct: it includes “elements such as combat secrecy, military deception, psychological warfare, electronic warfare, physical destruction of C2 infrastructure, and computer network warfare”. Above all, though, according to the United States, these IOs are, for China, a pre-emptive weapon, a non-conventional weapon, for asymmetrical conflicts.

The 2003 report also reiterates the importance of reserve units in the organization of IOs and IW, and states that China is setting up specialized units, in various cities throughout the country, thus forming a corps of cyberwarriors: “Specialized IO/IW reserve units are active in several cities developing “pockets of excellence” that could gradually develop the expertise and expand to form a corps of “network warriors” able to defend China’s telecommunications, command, and information networks, while uncovering vulnerabilities in foreign networks”.

According to the same report, the Chinese army possessed the means to carry out attacks on networks in armed conflicts: “Special information warfare units could attack and disrupt enemy C4I, while vigorously defending PRC systems”.

The 2004 report240 estimates that China’s IO capabilities are expanding and improving, although its “equipment is dated and does not appear to be readily available to most units”. However, the report predicts that: “domestic production, along with foreign technology transfers, probably will give the PLA access to a wider range of modern equipment in the future”. It also states that: “China is experiencing a rapid buildup of its information technology capabilities”. The rapidity of Chinese technological progress is founded largely on the acquisition of foreign technologies, technology transfers, knowledge-sharing, the installation in China of R&D centers for foreign companies, and the creation of joint ventures. Economic, industrial and research partnerships are thus helping speed up the process of modernization of the Chinese army.

One of the central subjects around which the American analysis pivots is the relationship between China and Taiwan, and the potential for that situation to evolve into an armed conflict. The scenario of this conflict thus serves as the background for the argument about Chinese development of IW capabilities, and is used to demonstrate the pertinence of the concerns formulated by the American observers: “During a cross-Strait conflict, China most likely would initiate an intensive perception management campaign, with both global and regional audiences, to reduce the desire of Taiwan to resist, justify China’s military campaign, and deter U.S. intervention”. Indeed, by controlling that information space, China would have the possibility to act quickly, to win a victory by playing with public perceptions (which are gold dust in psychological operations), and attacking the critical infrastructures and command systems of the enemy country. China could use information space to its advantage at every stage of the offensive operation: “China anticipates that this strategy will succeed because of the fragility of the Taiwan population’s psychology. The Chinese perception management campaign most likely would use Chinese, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other regional media to deliver messages to the Taiwan people and leaders. Unclassified Chinese writings reveal that attacking C4I systems, civilian information technology, and communication infrastructure are critical for gaining information superiority. Prior to an attack, Chinese information operations personnel and special forces or espionage agents most likely would gain and maintain access to such communication nodes for intelligence exploitation and disrupt critical infrastructure, such as the power grid and vulnerable collocated military and civilian telecommunications. Exploiting other portions of the information operations spectrum (through electronic warfare and denial and deception) also could disrupt Taiwan’s defenses, and attacks against unclassified DoD computer networks related to logistics could delay U.S. efforts to intervene”.

China’s capabilities are deemed entirely sufficient to be able to carry out operations against Taiwan. The report notes that Taiwanese experts have suggested their armed forces begin to prepare for this new kind of attack. Taiwan has high-level technologies and high-level engineers at its disposal, and can use them for its cyberdefense.

The 2005 report241 speaks not of “cyber”, but rather of “information technologies” and “Computer network operations”. The report highlights the emergence of a new expression in China’s vocabulary surrounding defense: "China’s latest Defense White Paper deployed authoritatively a new doctrinal term to describe future wars the PLA must be prepared to fight: “local wars under conditions of informationalization”. This term acknowledges the PLA’s emphasis on information technology as a force multiplier and reflects the PLA’s understanding of the implications of the revolution in military affairs on the modern battlefield”. This formulation defines the extent of the Chinese use of IW capabilities, whose development is continuing apace: “The PLA continues to improve its potential for joint operations by developing a modern, integrated command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) network and institutional changes”.

The report describes the components of information operations using a referential framework which is very similar to that employed by the US Department of Defense, notably distinguishing between CNO242, CNA243, CNE244 and CND245: “China’s computer network operations (CNO) include computer network attack, computer network defense, and computer network exploitation. The PLA sees CNO as critical to seize the initiative and “electromagnetic dominance” early in a conflict, and as a force multiplier”.

Specialists in Chinese affairs speak of the Chinese technique of Integrated Network Electronic Warfare. The report also stresses the lack of a formal Chinese doctrine concerning operations in cyberspace. This lack of official references, of a publically-available doctrine, destabilizes the United States, who must continue to pressure China to communicate about its projects, developments, capabilities, doctrines, etc., as the US does.

The 2006246, 2007247, 2008248, 2009249 and 2010 reports250 reiterate the observations on the same points:

In 2008258, the report alludes to the cyber-attacks originating in China, affecting networks all over the world:

– “In the past year, numerous computer networks around the world, including those owned by the U.S. Government, were subject to intrusions that appear to have originated within the PRC.”259 Although the attacks require particular capabilities and skills, there is, as yet, nothing to unequivocally indicate that they were the work of the Chinese army. Yet the very mention of the possibility of the Chinese army’s involvement is, in itself, a thinly-veiled accusation: “Although it is unclear if these intrusions were conducted by, or with the endorsement of, the PLA or other elements of the PRC government, developing capabilities for cyberwarfare is consistent with authoritative PLA writings on this subject”.260 The report also mentions other actors on the international scene who have openly laid blame at China’s door: “Hans Elmar Remberg, Vice President of the German Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Germany’s domestic intelligence agency), publicly accused China of sponsoring computer network intrusions “almost daily”261.

The 2009 report262 introduces the notion of cyber-warfare. The chapter entitled “Cyber-warfare” discusses the cyberattacks suffered by the US government, which are suspected (though cannot be proven) to have been carried out by the Chinese authorities. The report cites a number of cases of cyber-attacks recorded the world over (India, Belgium, the US), indicating the extent of the phenomenon: this is not merely a question of conflict between China and the United States.

The 2010263 and 2011264 reports take the same approach, citing a number of cyber-attacks recorded all over the world. These operations are classified as espionage activities, because the factor they have in common is the exfiltration of (often sensitive) data – e.g. strategic or military data. Although the 2010 report speaks of “cyber-warfare”, it often comes back to the notion of “IW”, and its psychological dimension, encompassed within the concept of the “Three Warfares” – a concept developed specifically by the Chinese army: “In 2003, the CCP Central Committee and the CMC approved the concept of “Three Warfares” (san zhong zhanfa), a PLA information warfare concept aimed at influencing the psychological dimensions of military activity”. These “three warfares” include Psychological Warfare, Media Warfare, and Legal Warfare. “The concept of the “Three Warfares” is being developed for use in conjunction with other military and non-military operations.”

The 2011 report265 defines what the United States views are the potential uses of the Chinese cyber capabilities: “Cyberwarfare capabilities could serve PRC military operations in three key areas. First and foremost, they allow data collection through exfiltration. Second, they can be employed to constrain an adversary’s actions employed to constrain an adversary’s actions based logistics, communications, and commercial activities. Third, they can serve as a force multiplier when coupled with kinetic attacks during times of crisis or conflict”. It also identifies sources of the Chinese doctrine – specifically two publications which have caught the attention of the American analysts: Science of Strategy and Science of Campaigns.

The question of cyberdefense cannot be reduced to the development of cyber capabilities and computer network operations. China is making an effort in the area of diplomacy by participating in multilateral and international fora, where it is often aligned with Russia – particularly in terms of promoting a vision of Internet governance. The United States is unhappy that China has not yet come around to its (the US) point of view, and accepted the application of international humanitarian law and the laws of war in cyberspace. Although it deals with cyber capabilities, the 2011 report preserves the notion of “IW”, highlighting the continuity of the Chinese policy of developing its capabilities in this domain for more than 10 years previously: “China is pursuing a variety of air, sea, undersea, space, counter space, information warfare systems, and operational concepts to achieve this capability, moving toward an array of overlapping, multilayered offensive capabilities extending from China’s coast into the western Pacific. [...] China is improving information and operational security to protect its own information structures, and is also developing electronic and information warfare capabilities, including denial and deception, to defeat those of its adversaries”. Later on in the same chapter, we find the same elements which have consistently been appearing since 2002, i.e., those relating to capability development, human resources, reservists, and strategic elements (CNO, CAN, CND and CNE).

In the 2012 report266, the notions of Information Warfare and Information Operations are absent this time.

The emphasis is again placed on the development of China’s capabilities: “In addition to the direct-ascent antisatellite weapon tested in 2007, these counter space capabilities also include jamming, laser, microwave, and cyber weapons”. At the heart of the concerns is the issue of cyber-espionage, in a section entitled “Cyber-espionage and Cyberwarfare Capabilities”, which begins by recapping the cyber-attacks carried out in 2011, stressing the nature of the targets affected. Up until then, the government’s and the army’s systems had been targeted. The report eagerly points out that private businesses have now fallen prey to the same operations. These allusions are reminiscent of the accusations of economic espionage carried out by the Chinese army for the benefit of the nation’s companies. These practices, which the US condemns, compound the differences of opinion regarding the means of governance of cyberspace. A section is given over to the economic espionage carried out by China, recalling that, of course, at least a dozen different nations conduct similar operations against the United States. China, however, appears to be the most active and the most persistent offender: “Chinese actors are the world’s most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage”.

The 2013 report267 touches on at least four aspects of cyberdefense: the developing Chinese power; the notions of pre-emptive weapons, informational superiority and asymmetry; economic cyber-espionage; and the code of conduct in the area of security.

China is firstly depicted as a power which has been in the process of development for over 10 years, but is now operational, according to the 2013 report: “The PLA has made huge progress in developing information technology and realizing information integration in recent years.”268 China is investing in the development of technological and cyber capabilities: “Beijing is investing in military programs and weapons designed to improve extended-range power projection and operations in emerging domains such as cyber, space, and electronic warfare.”

The PLA’s operations are considered as pre-emptive action weapons, with the aim of achieving informational superiority; this would enable China to combat superior adversaries (asymmetrical conflict, the equalizing nature of cyberspace). This informational superiority also contributes to its so-called Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

The report points out that in 2010, in China’s 2010 Defense White Paper, the PCR itself expressed concern over the cyberwarfare programs run by foreign nations. Each party (the US, China and other nations) thus believes itself to be in the right in its cyberdefense projects and measures, because the strategy is shared by all the major actors on the international stage.

According to the US Department of Defense, the development of cyber capabilities for warfare is consistent with Chinese military doctrine. The report, once again, draws on two reference documents from the Chinese body of strategic literature: Science of Strategy and Science of Campaigns. These two texts refer to information warfare, rather than cyber-operation directly.

The finger is also pointed at China for its practices of economic cyber-espionage, aimed at obtaining advanced foreign technologies: “Numerous computer networks, including those owned by the US government, were targeted for intrusion, some of which were attributable to the Chinese government and military.”269 The accusation is direct: “China is using its computer network exploitation (CNE) capability to support intelligence collection against the U.S. diplomatic, economic, and defense industrial base sectors that support U.S. national defense programs.”

China, along with Russia, is also internationally promoting its proposed Information Security Code of Conduct, which is intended to affirm the principle of exercising of the right of sovereignty over content and information flow.

All of this makes China a threat. Firstly, its technological capabilities in cyberspace (which give China the means to carry out offensive operations); and secondly the anti-access strategy is a threat to the freedom of projection of the American forces in the Pacific region. These observations have been being formulated since the beginning of the 2000s by the United States. China’s practices (economic cyber-espionage) and its objectives (the Code of Conduct) are contrary not only to the United States’ interests (of course), but also its values. There is a significant difference of opinion on these points.

8.2.2. Speeches of the Secretaries of Defense

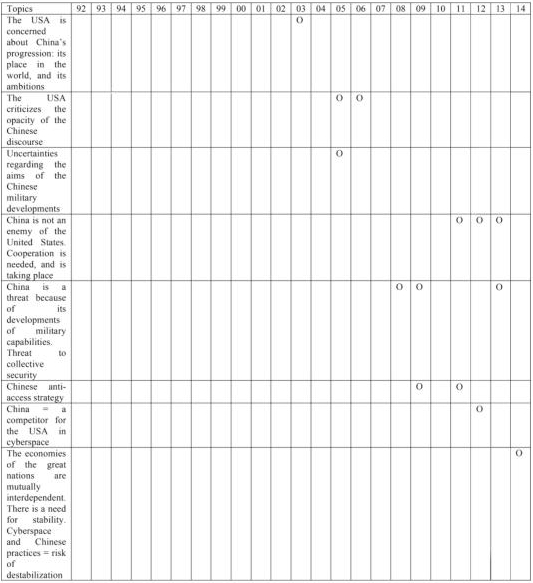

China has essentially been part of the discourse of the US Secretaries of Defense from the start of the 2000s. Chronologically, this corresponds to the date of establishment of the annual reports on Chinese military development produced by the Department of Defense, in accordance with the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2000, Section 1202, Public Law 106-65.

Whilst, in general terms, the speeches of the successive Secretaries of Defense between 1995 and 2014 increasingly discuss the issue of “cyber”, when we analyze the whole of the available corpus, we can see that China is not remotely associated with that issue until 2008, but that from that point on, the China issue becomes more apparent. Thus, between 2000 and 2007, the Chinese are mentioned essentially because of the concerns that they raise:

– because of the increasingly important role China is assuming on the international stage, and the uncertain prospects for its evolution: “…I don’t think it’s written exactly how they’re going to enter the world, goodness knows all the countries in the region and in the world are working to try to see that they enter the global community in a peaceful, rational way, without any grinding of gears”;270

– there are many unknowns in the equation – particularly in relation to the true efforts made by China in terms of military development, and in relation to China’s intentions (is this development of capability for peaceful or aggressive ends?): “Among other things, the report concludes that China’s defense expenditures are much higher than Chinese officials have published. It is estimated that China’s is the third largest military budget in the world, and clearly the largest in Asia. China appears to be expanding its missile forces, allowing them to reach targets in many areas of the world, not just the Pacific region, while also expanding its missile capabilities within this region. China also is improving its ability to project power, and developing advanced systems of military technology. Since no nation threatens China, we must wonder: Why this growing investment? Why these continuing large and expanding arms purchases? Why these continuing robust deployments? Though China’s economic growth has kept pace with its military spending, it is to be noted that a growth in political freedom has not yet followed suit. With a system that encouraged enterprise and free expression, China would appear more a welcome partner and provide even greater economic opportunities for the Chinese people”;271

– the nature of the diplomatic relations, when an incident occurs between the two countries: “A few months ago, as we all know, an unarmed EP-3 reconnaissance aircraft flying in the airspace over the China Sea was struck by a Chinese fighter and, of course, for a while we had 24 of our great personnel detained. Some ask why are we conducting surveillance against another nation? My answer to that is, “That’s what we do.” We are vigilant, we are watchful because we know that our interests and those of our allies in the region may be challenged and we must be ready”;272

– generally speaking, the United States criticize the Chinese approach for its opacity, the lack of transparency regarding China’s intentions and methods, and wonders about the effect such a stance might have on international relations: “China has a strong economic growth rate today and an industrious workforce. But there are aspects of China's actions that can complicate their relationships with other nations. As we discussed last year, a lack of transparency with respect to their military investments understandably causes concerns for some of their neighbors.”273

Regardless of the concerns, and of the developments of capabilities, the Secretary of Defense points out that the Sino-American relation cannot be envisaged as a hostile one: “I disagree with those who portray China as an inevitable strategic adversary of the United States.”274

Although this statement was made in 2011, from 2008 onwards the discourse has evolved. China has become a more openly apparent threat by virtue of the level of its defense capabilities: “In the case of China, investments in cyber-and anti-satellite warfare, anti-air and anti-ship weaponry, submarines, and ballistic missiles could threaten America’s primary means to project power and help allies in the Pacific: our bases, air and sea assets, and the networks that support them.”275 Now, therefore, the question of Chinese cyberwarfare capabilities arises.

The remarks were repeated in very similar terms the following year: “As we know, China is modernizing across the whole of its armed forces. The areas of greatest concern are Chinese investments and growing capabilities in cyber-and anti-satellite warfare, anti-air and anti-ship weaponry, submarines, and ballistic missiles.”276 Rather than the capabilities for symmetrical conflict, cyberdefense contributes to the Chinese anti-access strategy, thus endangering America’s abilities to project power and intervene in the Pacific region: “In fact, when considering the military-modernization programs of countries like China, we should be concerned less with their potential ability to challenge the U.S. symmetrically – fighter to fighter or ship to ship – and more with their ability to disrupt our freedom of movement and narrow our strategic options. Their investments in cyber and anti-satellite warfare, anti-air and anti-ship weaponry, and ballistic missiles could threaten America’s primary way to project power and help allies in the Pacific – in particular our forward air bases and carrier strike groups. This would degrade the effectiveness of short-range fighters and put more of a premium on being able to strike from over the horizon – whatever form that capability might take.”277

This concern did not disappear, because in 2011 the Secretary of Defense put forward the same arguments: “As I alluded to earlier, advances by the Chinese military in cyber and anti-satellite warfare pose a potential challenge to the ability of our forces to operate and communicate in this part of the Pacific. Cyber-attacks can also come from any direction and from a variety of sources – state, non-state, or a combination thereof – in ways that could inflict enormous damage to advanced, networked militaries and societies. Fortunately, the U.S. and Japan maintain a qualitative edge in satellite and computer technology – an advantage we are putting to good use in developing ways to counter threats to the cyber and space domains.”278 The concern expressed here is barely tempered by the certainty of a technological advantage on the part of the United States and Japan.

In view of the number of speeches given by the Secretaries of Defense, those which speak about the issue of Chinese cyberwarfare are, in the final analysis, relatively few.

Defense relations with China need to take place in a climate of cooperation, and encourage exchanges: “We also need you to strengthen defense ties with China. China’s military is growing and modernizing. We must be vigilant. We must be strong. We must be prepared to confront any challenge. But the key to peace in that region is to develop a new era of defense cooperation between our countries – one in which our militaries share security burdens to advance peace in the Asia-Pacific and around the world.”279

During his visit to Beijing in September 2012, Leon Panetta mentioned the cyberspace issue: “We’ve made it very clear that our engagement will continue to be guided by our adherence to a set of basic principles, including the following: one, free and open commerce; two, a just international order that emphasizes the rights and responsibilities of nations and the fidelity to the rule of law; three, open access by all to the shared domains of sea and air and space and cyberspace; and, lastly, resolving disputes peacefully, without coercion or the use of force.”280

In a speech delivered in New York in 2012, Leon Panetta pointed to the United States’ direct competitors in cyberspace, whose strategies lend legitimacy to the process of reinforcing America’s cyberdefense resources: “Our most important investment is in skilled cyber-warriors needed to conduct operations in cyberspace. Just as DoD developed the world’s finest counterterrorism force over the past decade, we need to build and maintain the finest cyber force and operations. We’re recruiting, we’re training, we’re retaining the best and the brightest in order to stay ahead of other nations. It’s no secret that Russia and China have advanced cyber capabilities. Iran has also undertaken a concerted effort to use cyberspace to its advantage.”281 In the same section, two types of threats are mentioned: terrorism, and the rise in power of the states of China, Russia and Iran. Leon Panetta identifies two major risks: that of the rise in capability, and that of the opacity, which could give rise to possible misunderstandings, incomprehension, doubts, and interpretation errors: “I recently met with our Chinese military counterparts just a few weeks ago. As I mentioned earlier, China is rapidly growing its cyber capabilities. In my visit to Beijing, I underscored the need to increase communication and transparency with each other so that we could avoid a misunderstanding or a miscalculation in cyberspace. This is in the interest of the United States, but it’s also in the interest of China.”282

China and cyberwarfare constitute a threat to the collective security of Europe and the United States, said Chuck Hagel in 2013, because they contribute to the global threat: “The foundation of our collective security relationship with Europe has always been cooperation against common threats. Throughout most of the 20thcentury, these common threats were concentrated in and around Europe. But today, the most persistent and pressing security challenges to Europe and the United States are global. They emanate from political instability and violent extremism in the Middle East and North Africa, dangerous non-state actors, rogue nations, such as North Korea, cyber-warfare, demographic changes, economic disparity, poverty and hunger. And as we confront these threats, nations such as China and Russia are rapidly modernizing their militaries and global defense industries, challenging our technological edge in defense partnerships around the world.”283 On the other hand, China has to play an active role in security – particularly in Asia: “No security architecture in Southeast Asia can succeed without the active involvement and participation of the two large emerging powers that border this region, China and India.”284

Cooperation with China has now been engaged in matters of Cybersecurity: “As part of our rebalance, the United States is committed to pursuing a positive and constructive relationship with China. We have very open discussions with China, including a productive visit last week by my counterpart, Defense Minister General Chang, whom I hosted at the Pentagon. He and I agreed that we must increase our cooperation and our mutual understanding, including through more defense exercises and the recently established U.S.-China Cyber Working Group. And we continue to encourage China to work toward greater transparency.”285

The DoD accuses China of cyber-attacks, whilst calling for greater cooperation and dialog on the issue: “We are also clear-eyed about the challenges in cyber. The United States has expressed our concerns about the growing threat of cyber intrusions, some of which appear to be tied to the Chinese government and military. As the world’s two largest economies, the U.S. and China have many areas of common interest and concern, and the establishment of a cyber working group is a positive step in fostering U.S.-China dialogue on cyber. We are determined to work more vigorously with China and other partners to establish international norms of responsible behavior in cyberspace.”286

In June 2014, Chuck Hagel delivered a speech at the National Defense University in Beijing. In it, he made mention of cyberspace several times:

– The economies of the great nations are mutually interdependent, but in order to prosper they require stability – particularly at a regional level. However, the threats arising in cyberspace are among the destabilizing factors liable to hamper economic expansion. In this respect, China and the United States have a shared interest (peace for/because of the economy): “As our economic interdependence grows, we have an opportunity to expand the prosperity this region has enjoyed for decades. To preserve the stable regional security environment that has enabled this historic economic expansion, the United States and China have a very big responsibility to address new, enduring regional security challenges alongside all the partners of the Asia-Pacific. We face North Korea’s continued dangerous provocations, its nuclear program, and its missile tests; ongoing land and maritime disputes; threats arising from climate change, natural disasters, and pandemic disease; the proliferation of dangerous weapons; and the growing threat of disruption in space and cyberspace.”287

– The United States wishes to decry Chinese practices (cyber-espionage) and also to find a solution; the Americans want greater communication and less opacity, and call on China to communicate about its cyber strategies, as the US does: “Openness and two-way communication is especially important in the area of strategic and emerging capabilities, and in managing regional security challenges. It is why we seek to resume a U.S.-China nuclear policy and strategy dialogue. It is also why, through our Cyber Working Group, the United States has been forthright in our concerns about Chinese use of networks to perpetrate commercial espionage and intellectual property theft. We’ve also made efforts to be more open about our cyber capabilities, including our approach of restraint. Those efforts recently took a major step forward when the Department of Defense, for the first time ever, provided to representatives of the Chinese government a briefing on DoD’s doctrine governing the use of its cyber capabilities. We’ve urged China to do the same.”288

– The United States will defend the principle of freedom of access to cyberspace: “Here in the Asia-Pacific and around the world, the United States believes in maintaining a stable, rules-based order built on free and open access to sea lanes and air space, and now, cyberspace”. The “freedom”, of course, relates to economic and security interests, but also to conflicting values (America’s desire to impose liberal democratic values on the whole of the world).

8.2.3. Prospective analyses conducted by the National Intelligence Council

The “Global Trends 2010” report289, published in November 1997, predicts that powerful states will lose some of their prerogatives because of the expansion of information technologies throughout the world: “governments whose states are relatively immune from poverty and political instability will still find that they are losing control of significant parts of their national agendas due to the globalization and expansion of the economy, and the continuing revolution in information technology”. The report also holds that “information technologies will continue to be the hallmarks of the revolution in military affairs”. These considerations about ICTs do not include the prefix particle “cyber”. Nor do they associate China with ICT issues. The authors of the report do not envisage China, in the short or medium term, becoming a genuine military power, as they imagine this process would be disrupted by the country’s internal problems (managing growth, urbanization, energy and food requirements, etc.).

“Global Trends 2015”290, published in December 2000, introduces the issue of the cyber threat – one of a variety of transnational problems which the United States is likely to have to face by 2015. The cyber threat is all the greater because American society is so heavily dependent on computer networks. Thus, this theme – a cyber threat posed to the critical infrastructures, and therefore to the whole of society – was already on the radar nearly 15 years ago: “Increasing reliance on computer networks is making critical US infrastructures more attractive as targets. Computer network operations today offer new options for attacking the United States within its traditional continental sanctuary—potentially anonymously and with selective effects. Nevertheless, we do not know how quickly or effectively such adversaries as terrorists or disaffected states will develop the tradecraft to use cyberwarfare tools and technology, or, in fact, whether cyberwarfare will ever evolve into a decisive combat arm”. China is not associated with the issue of a cyber threat. It is, however, associated with the threat of Weapons of Mass Destruction: “Short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, particularly if armed with WMD, already pose a significant threat overseas to US interests, military forces, and allies. By 2015, the United States, barring major political changes in these countries, will face ICBM threats from North Korea, probably from Iran, and possibly from Iraq, in addition to long-standing threats from Russia and China.”

The report “Global Trends 2020, Mapping the Global Future”291, published in 2004, tackles the question of cyber-warfare, which is the title of one of its chapters.292 Major cyber-attacks are likely to be attributable to terrorism. (“Bioterrorism appears particularly suited to the smaller, better-in found groups. We also expect that terrorists will attempt cyber-attacks to disrupt critical information networks and, even more likely, to cause physical damage to information systems”) rather than to a State such as China. When the report speaks of China, it is not to describe it as presenting a cyber threat, but rather to highlight its vulnerability to economic instability and its progress in terms of knowledge production (China produces more graduates than any other major power – a process which will undoubtedly help it to eventually overcome its technological out datedness), and its capacity to create a regional security order in case the Americans withdraw.