4

Unconventional, Stretch Collaboration

Is Becoming Essential

One doesn’t discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.

—André Gide1

For most people, stretch collaboration is unfamiliar and uncomfortable.

STRETCHING CREATES FLEXIBILITY AND DISCOMFORT

John and Mary are dealing with their son Bob, who has again fallen behind on his mortgage payments. But this time they are trying to employ stretch instead of conventional collaboration.

The three of them feel a loving family connection, but they also admit that they are coming at this situation with different experiences and perspectives and needs. They talk openly and vehemently about these differences: John says that he feels angry and helpless in the face of his son’s problems; Mary says that she is worried for her grandchildren and also that her and John’s own plans for a comfortable retirement will be put in jeopardy; and Bob says that he is putting all of his energy into his struggling small business and wishes that his family would be supportive rather than only critical. This fight is upsetting and also relieving: they still don’t see eye to eye, but they all feel better understood.

They realize that they do not agree on what their real problem is or on what the solution is—maybe they never will agree and maybe they actually don’t know. But they are willing to try out some modest new actions that they think could help. John guarantees a bank loan to Bob’s company; Mary helps Bob’s wife, Jane, look for a job; the two couples talk together about their situation; Bob and John spend Saturdays together with the grandchildren. It’s not that their challenges suddenly get easier, but their greater openness enables them to see and try out some new possibilities. Bob and Jane’s finances start to improve.

The four of them also back off from trying to change what the others are doing—which, in any case, has not been successful. Instead, they each consider what they themselves might do differently. John makes an effort to connect with Bob on matters other than finances; Mary stands up to John more strongly; Bob talks with a small-business advisor; and Jane takes control of their household budget.

These shifts all help lessen the anger and frustration they feel toward one another and toward their situation. The financial and emotional pressures on them have not gone away and could still overwhelm them. But now they are more able to deal with these pressures thoughtfully and as a family.

All of them find this shift from conventional to stretch collaboration to be difficult. They feel uncomfortable to be stretching: opening up both to greater conflict and to more genuine connection, trying out unfamiliar new actions that may not work, and accepting their own roles in and responsibilities for what is happening. But they are hopeful that this different approach will work better.

HOW TO END A CIVIL WAR

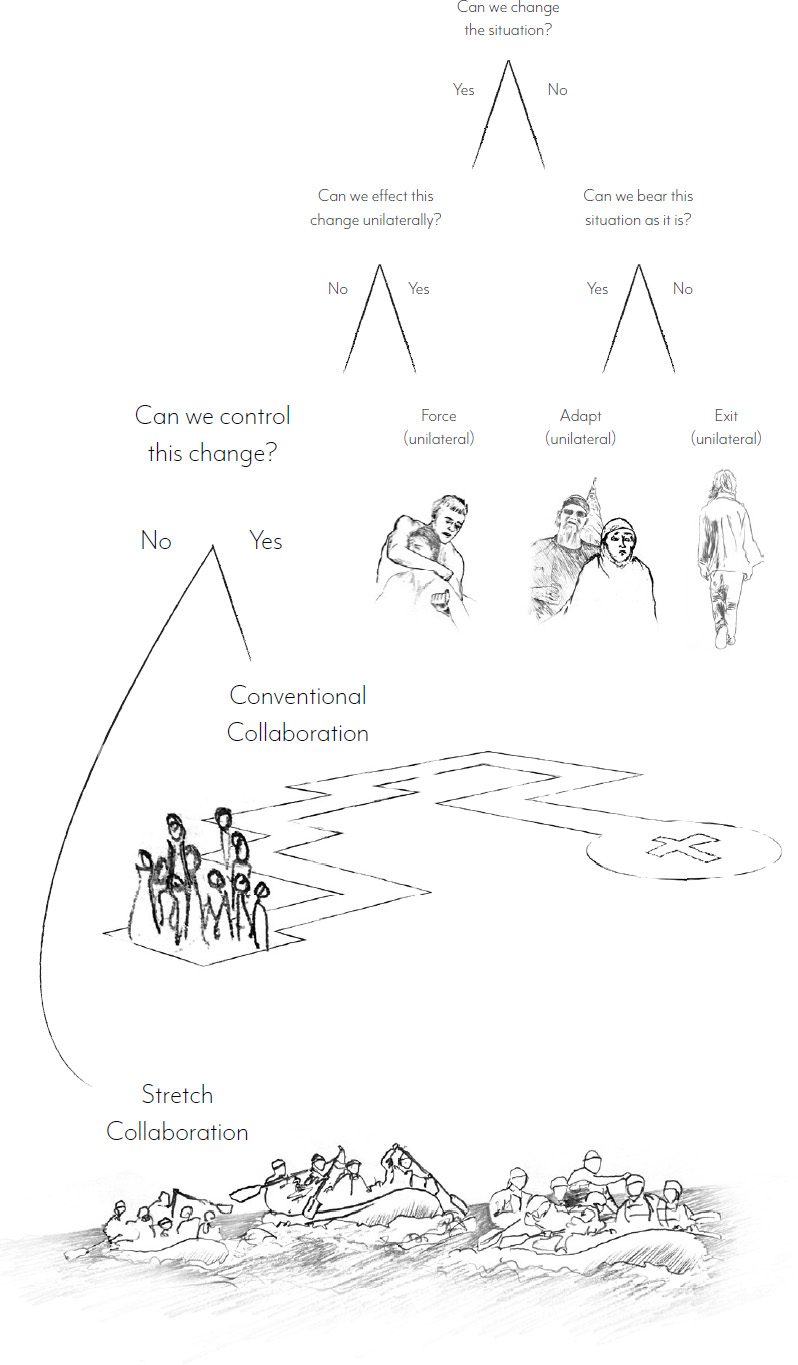

If we cannot address our challenges through forcing, adapting, or exiting, then we will need to employ collaboration. And if our challenge is complex and contentious, then the conventional approach to collaboration will not work and we will need to employ an unconventional one.

My experience in South Africa in 1991 gave me a glimpse of such an unconventional approach. But it was only later, in Colombia, that I was able to make out clearly how this new approach worked and how it differed from the conventional one I had been trained in.

Colombia was, since the 1960s, one of the most violent countries in the world, with armed clashes among the military, the police, two left-wing guerrilla armies, right-wing paramilitary vigilantes, drug traffickers, and criminal gangs. This conflict killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and forced millions to flee their homes.

In 1996, a young politician named Juan Manuel Santos visited South Africa and met with Nelson Mandela, who told him about the Mont Fleur project. Santos thought that such a collaboration might help Colombians find a way out of their conflict. He organized a meeting in Bogotá to discuss this possibility and invited me to participate.

The meeting involved generals, politicians, professors, and company presidents. Several leaders of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) participated by radio from a hiding place in the mountains. The participants were both excited and nervous to find themselves in such a heterogeneous group. One Communist Party city councilor, spotting a paramilitary warlord across the room, asked Santos, “Do you really expect me to sit down with this man, who has tried to have me killed five times?” Santos replied, “It is precisely so that he does not do so a sixth time that I am inviting you to sit down.”2

Out of this meeting the collaborative project named Destino Colombia was initiated.3 An organizing committee convened a team of forty-two people that represented the conflict in miniature: military officers, guerrillas, and paramilitaries; activists and politicians; businesspeople and trade unionists; landowners and peasants; academics, journalists, and young people.

This team met three times over four months, for a total of ten days, at a rustic inn outside of Medellín. Both of the illegal, armed, left-wing guerrilla groups, the FARC and the smaller National Liberation Army (ELN), participated. Although the government offered them safe passage to the workshops, the guerrillas thought this would be too risky, so we arranged for them to participate in the team’s meetings by telephone. Three men called in from the political prisoners’ wing of a maximum-security prison and one from exile in Costa Rica.

Most members of the team were talking with the guerrillas for the first time and were frightened of retribution for what they might say. We communicated using two speakerphones in the meeting room. When people walked by the speakerphones, they gave the phones a wide berth, afraid to get too close. When I mentioned this fear, one of the guerrillas observed that our microcosm was reflecting the macrocosm: “Mr. Kahane, why are you surprised that people in the room are frightened? The whole country is frightened.” Then he promised that the guerrillas would not kill anyone for anything said in the meetings.

Jaime Caicedo was the secretary general of the far-left Colombian Communist Party, and Iván Duque was a commander of the far-right paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). One evening, Caicedo and Duque stayed up late talking and drinking and playing the guitar with Juan Salcedo, a retired army general. The next morning, Caicedo wasn’t in the meeting room when we were due to start, and I asked the group where he was. They made jokes about what might have happened to him. One person said, “The general made him sing.” Then Duque said, menacingly, “I saw him last.” I was concerned that Caicedo had been murdered and was relieved when a few minutes later he walked into the room.

(Years later I heard a revealing coda to this story. Duque had gone into the jungle to meet his boss, Carlos Castaño, the notorious head of AUC. Castaño excitedly told Duque that AUC fighters had discovered the location of their archenemy Caicedo and were on their way to assassinate him. Duque pleaded for Caicedo’s life, telling Castaño the story of that evening together at the scenario workshop and saying, “You can’t kill him; we were on the Destino Colombia team together.” After much arguing, Castaño called off the assassination. I interpreted this story as exemplifying the transformative potential of such collaborations: to be willing to defy Castaño on this matter of life and death, Duque must have transformed his sense of his relationship with Caicedo and of what he himself needed to stand for and do.)

As the work progressed, the team members became less afraid and more willing to speak frankly. Businessman César De Hart said that he had firsthand experience of the conflict with the guerrillas, did not trust them at all, and believed that the country’s best hope for peace would be to intensify the military campaign against them. It took courage for him to say this because he was directly challenging not only the guerrillas but also the rest of the team and their hopeful belief that a peaceful solution was possible. He was willing to be open and confrontational, and the team’s relationships were now strong enough to hear such a statement without rupturing. Furthermore, when De Hart said exactly what he was thinking and feeling, the fog of conceptual and emotional confusion that had filled the room lifted, and we could all see clearly this mistrust and the possibility of intensified conflict that it implied.

By the end of their third workshop, the team had agreed on four scenarios. The first, “When the Sun Rises We’ll See,” was a warning of the chaos that would result if Colombians just let things be and failed to address their tough challenges (this scenario, in terms of the Thai framework, exemplified adapting). The second, “A Bird in the Hand Is Worth Two in the Bush,” was a story of a negotiated compromise between the government and the guerrillas (conventional collaborating). The third, “Forward March!” was the story foreshadowed in De Hart’s suggestion that the government crush the guerrillas militarily and pacify the country (forcing). The fourth, “In Unity Lies Strength,” was a story of a bottom-up transformation of the country’s mentality toward greater mutual respect and cooperation (stretch collaborating). The team did not agree on which solution to the conflict was most likely or best, so they presented these narratives to their fellow citizens, in newspaper articles and television broadcasts and small and large meetings all around the country, simply as alternative possibilities.

After Destino Colombia, my Colombian colleagues organized several follow-up multistakeholder processes that I facilitated. In one meeting, a group was wrestling with a difficult issue when a politician demanded that they agree on a certain point of principle. I thought that such an agreement would not be possible at that time and urged the group to carry on without agreement, and they did. I was surprised that by the end of the meeting they had agreed to work together on several initiatives, notwithstanding their earlier nonagreement.

The next day, I related this puzzling incident to Antanas Mockus, a former mayor of Bogotá. “Often we do not need to have a consensus on or even to discuss principles,” he said. “The most robust agreements are those that different actors support for different reasons.” I now understood that people who have deep disagreements can still get important things done together. The bar for making progress on complex challenges is therefore not as high as most people think: we do not need to agree on what the solution is or even on what the problem is.

Over the decades that followed, I was gratified to see that the scenarios and the extraordinary process that produced them remained a touchstone in conversations among Colombians about what they could and should do. At different times over these years, each of the four scenarios seemed to explain what was happening in the country, so these narratives continued to help Colombians make sense of their situation. In 2010, Santos was elected president of the country, and he characterized his government’s program as an enactment of “In Unity Lies Strength.”

In 2016, Santos finally succeeded in negotiating a peace treaty with the FARC and initiating one with the ELN, and for this he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. On the day of this award, his official website posted a note that characterized the first meeting he had organized with me twenty years before as “one of the most significant events in the country’s search for peace.”4

I knew that over the intervening years there had been many different large-scale efforts to resolve the conflict, so I was surprised at the significance that Santos assigned to Destino Colombia. I asked Alberto Fergusson, a psychiatrist and friend of Santos, about this. Fergusson’s explanation was that for Santos, the crucial lesson of Destino Colombia, which had animated his political work ever since, was that—contrary to received wisdom—it is possible for people who hold contradictory positions to find ways to work together.

The Destino Colombia project helped Colombians work together in a way that contributed to ending a fifty-two-year civil war. This project exemplifies in three ways the stretch approach to collaboration.

First, the Destino Colombia team members were not simply trying to solve one single problem or to optimize one superordinate good, even though their rhetoric was that they were collaborating for the good of Colombia. They were in the middle of a conflict and did not agree on what the solution was or even on what the problem was. They agreed only that the situation they were facing was problematic, and they viewed it as problematic in different respects and for different reasons.

Although the team enjoyed working together and felt some commitment to one another, they were not simply or only one team. They all had stronger connections and commitments to their own organizations and communities (Duque’s effort to save Caicedo was the exception that proved this rule). This non-unity was what made their work together so contentious and also so rich and valuable. They collaborated, then, without having a single focus or goal.

Second, the team did not agree on a plan for what should be done in the country. They agreed only that there were four scenarios as to what could happen and that they didn’t want the first, status quo, one. Everything else they (and others who made use of the scenarios) did, they worked out as they went along, over the years that followed. So they collaborated without having a single vision or road map.

And third, although the team members held strong views about what ought to happen, they weren’t able to compel the others to go along. Here again, the microcosm reflected the macrocosm: the war had gone on so long because no party was able to impose its will on the others. So the team collaborated without being able to change what others were doing.

STRETCH COLLABORATION ABANDONS THE ILLUSION OF CONTROL

Destino Colombia highlights the ways in which our conventional understanding of collaboration is constricted. Stretch collaboration requires us to stretch in three dimensions; in all of these, stretch collaboration includes and goes beyond conventional collaboration (see page 2).

In summary, conventional collaboration assumes that we can control the focus, the goal, the plan to reach this goal, and what each person must do to implement this plan (like a team following a road map). Stretch collaboration, by contrast, offers a way to move forward without being in control (like multiple teams rafting a river).

The first dimension is how we relate to the people with whom we are collaborating—our team. In conventional collaboration, we maintain a controlled and constricted focus on achieving harmony in the team and the good and the objectives of the team as a whole. But in complex and uncontrolled situations, we cannot maintain such a focus because the members of the team have significantly different perspectives, affiliations, and interests, and are free to act on these. So we have to stretch to open up to, embrace, and work with the conflict and connections that exist within and beyond the team.

Five Ways to Deal with Problematic Situations

The second dimension is how we advance the work of the team. In conventional collaboration, we focus on reaching clear agreements on the problem we are trying to solve, the best solution to this problem, and the plan to implement this solution, and then on executing this plan as agreed. But in complex, uncontrolled situations, we cannot achieve such definitive agreements or predictable execution, because the team members do not agree with or trust one another and because the results of the team’s actions are unpredictable. So we have to stretch to experiment with—try out—multiple perspectives and possibilities in order to discover, one step at a time, what will work and move us forward.

The third dimension is how we participate—what role we play—in the situation we are trying to address. In conventional collaboration, we focus on how to get people to change what they are doing so that we can successfully execute our plan. Implicitly we mean getting other people to change what they are doing; we see ourselves as outside of or above the situation. But in complex, uncontrolled situations this is simply impossible: we cannot get anyone to do anything. So we have to stretch to step fully into the situation and to be open to changing what we ourselves are doing.

To be able to collaborate successfully in complex situations, we must stretch in all three of these dimensions. These stretches are unfamiliar and uncomfortable. The next three chapters lay out how to make these stretches.