5

The First Stretch Is to Embrace

Conflict and Connection

Though it all may be one in the higher eye

Down here where we live it is two.

—Leonard Cohen1

In conventional collaboration, we focus on working harmoniously with our team members to achieve what is best for the whole team. We talk rather than fight. This approach works when we are in simple situations that are under control: when all of our perspectives and interests are, or can be made to be, congruent. But when we are in complex, uncontrolled situations where our perspectives and interests are at odds, we need to search out and work with our conflicts as well as our connections. We need to fight as well as talk.

DIALOGUE IS NOT ENOUGH

The most profound experience I have had in collaborating is also the one that raised the most confusing questions. Between 1998 and 2000, I facilitated a project in Guatemala to help implement the peace accords that ended that country’s genocidal thirty-six-year civil war. The project brought together leaders of many of the factions that had been caught up in this brutal conflict: cabinet ministers, former army and guerrilla officers, businessmen, indigenous people, journalists, youth. The understandings and relationships and commitments that this project generated produced many important initiatives to repair Guatemala’s torn social fabric. United Nations representative Lars Franklin said that this project planted and nurtured many seeds, including four presidential campaigns; contributions to the Commission for Historical Clarification, the Fiscal Agreement Commission, and the Peace Accords Monitoring Commission; work on municipal development strategies, a national antipoverty strategy, and a new university curriculum; and six spin-off national dialogues.2

One pivotal event in the work of this team occurred on the final morning of their first workshop. They were sitting in a circle, telling stories about their personal experiences of the war. A man named Ronald Ochaeta, a human rights worker for the Catholic Church, talked about the time he had gone to an indigenous village to witness the exhumation of a mass grave from one of the war’s many massacres. Once the earth had been removed, he noticed a number of small bones and asked the forensic scientist if people had had their bones broken during the massacre. The scientist replied that, no, the grave contained the corpses of pregnant women, and the small bones were those of their fetuses.

When Ochaeta finished telling his story, the team was completely silent. I had never experienced a silence like this and was struck dumb. The silence seemed to last five minutes. Then it ended and we carried on with our work.

This episode made a profound impact on the team and on me. When team members were interviewed five years later for a history of the project, many of them traced the important work that they had subsequently done together to the insight and connection manifested in those minutes of silence. One of them said, “After listening to Ochaeta’s story, I understood and felt in my heart all that had happened. And there was a feeling that we must struggle to prevent this from happening again.” Another said, “In giving his testimony, Ochaeta was sincere, calm, and serene, without a trace of hate in his voice. This gave way to the moment of silence that, I would say, lasted at least one minute. It was horrible! It was a very moving experience for all of us. If you ask any of us, we would say that this moment was like a large communion.”3 In a Catholic country like Guatemala, to refer to a moment of team communion means a moment of a team being one body.

The story of the five minutes of silence in Visión Guatemala became the crowning chapter in my first book, Solving Tough Problems. It epitomized my understanding (which originated at Mont Fleur) that connecting with others, and through this revealing and repairing the social whole, was the key to collaboration. The experiences I had with such connecting, in this and other projects, also satisfied my own longing to engage harmoniously with others and with something larger than myself.

In 2008, I went back to Guatemala for the tenth anniversary of the project. I was happy to see my colleagues again but also concerned by what was happening there: a deepening economic crisis; increasingly serious threats from organized crime and elements of the military; and disappointment in the new government, led by our Visión Guatemala teammate, now president, Álvaro Colom. I was interested in what the team thought of the work we had all done together, which I had written about so enthusiastically.

I had lunch with one of my friends, a leftist researcher and activist named Clara Arenas. She knew how significant I had found the dialogue in our team, so she pointedly told me that she and her colleagues had recently become so frustrated with the poor results from the many dialogues that were taking place in Guatemala that they had taken out a full-page newspaper advertisement saying they would no longer participate in these processes. They did this because the government expected that the organizations participating in dialogues would meanwhile desist from organizing strikes and marches and other forms of popular resistance. Arenas and her colleagues were not willing to demobilize—to abandon one of the primary means they had to achieve their objectives. And if they couldn’t mobilize to assert their perspectives and positions, then they weren’t willing to dialogue to engage with the government. I admired Arenas and knew that she was telling me something important. But I couldn’t fit it into the way I understood collaboration, so it stayed with me as an unresolved tension.

Five years later, I had three experiences that showed me how to resolve this tension.

In October 2013, I had a sharp interaction with David Suzuki at a meeting of the board of his foundation in Vancouver. Suzuki is a Canadian geneticist who has presented popular radio and television shows on science for more than forty years. He is an outspoken environmentalist and is among the country’s most respected public figures. At that time, he was in the middle of a momentous battle among environmentalists, fossil fuel companies, and the federal government over how Canada should deal with climate change, especially the high carbon dioxide emissions from its oil sands projects.

Before the meeting, I had read one of Suzuki’s speeches in which he had said that he would be willing to engage with the CEO of a consortium of oil sands companies only if the CEO would “agree on certain basic things”—for example, that “we are all animals, and as animals our most fundamental need, before anything else, is clean air, clean water, clean soil, clean energy and biodiversity.”4 I thought that Suzuki’s insistence that he would dialogue only if the principles he believed in were agreed to in advance was unreasonable and unproductive, and at the meeting I challenged him about this. His position was that given the absence of agreement on such fundamental matters, it was better for him not to engage, so he was instead going to focus his energies on mobilizing public and political opinion in support of the principles he believed in.

This brief exchange struck me. I had heard a similar argument many times from other people in other contexts: that the principles they were asserting were right and needed to be accepted as the starting point for any collaboration. I had always confidently dismissed these arguments on the grounds that such disagreements over principles were usually the reason why collaborations didn’t occur, and that agreement could be reached only through—not prior to—engagement and collaboration. But Suzuki’s provocation stayed with me, because the principles he was asserting seemed correct and because I held him in such high esteem that I could not easily dismiss his argument.

I could now see that engaging and asserting were complementary rather than opposing ways to make progress on complex challenges, and that both were legitimate and necessary. Different kinds of asserting—debates, campaigns, competitions, rivalries, marches, boycotts, lawsuits, violent confrontations—are part of every story of systemic change. Asserting and counter-asserting inevitably create discord and conflict. But I thought that perhaps some people and organizations could do the asserting while others did the engaging; I had heard activists refer to “outside the room” and “inside the room” roles in efforts to effect change. I hoped that this complementarity meant that others could focus on asserting and I could maintain my comfortable focus on engaging.

In early December 2013, I got home to South Africa, and a few days later Nelson Mandela passed away. For weeks, local and international newspapers were filled with obituaries and reflections on his life and legacy. I also reflected on my understanding of his biography, with which my own had become intertwined. By 2013, social and political relations among South Africans had become more fractious and less forgiving, and many were reevaluating the success of the “miraculous” 1994 transition that Mandela had led.

Now, with this coming right after my exchange with Suzuki, I realized that in focusing so much on Mandela’s efforts to achieve his objectives through engaging and dialoguing with his opponents, I had downplayed his efforts to achieve these same objectives through asserting and fighting. Before Mandela went into prison, he had led illegal marches and other campaigns against the apartheid government, gone underground and made clandestine trips abroad, and served as the first commander of the armed guerrilla wing of the African National Congress (as late as 2007, ANC leaders were still being denied visas to enter the United States on the grounds that they had been members of a terrorist organization). After Mandela was released, during the negotiations leading up the 1994 elections and then during his presidential term, he often pushed his opponents hard to advance his positions.

A more complete picture of Mandela’s leadership, I could now see, showed that he knew how and when to engage, and how and when to assert. The extraordinary transition in South Africa had been effected through Mandela and others employing both engaging and asserting. In thinking about my own work, I realized that I had been focusing only on the part of the picture in which I had been physically present: although I usually met the people I worked with in workshops designed to enable them to dialogue with one another, most of them spent a lot of their time outside the workshops fighting one another. In fact, this fighting was what made the workshop dialogues so remarkable and useful. So now I wondered whether the engaging and asserting roles could really, as I had been hoping, be kept separate.

Then, in Thailand in May 2014, after months of violent We Force confrontations, the army staged its coup. Some of my Thai colleagues were outraged at this antidemocratic action. Others were relieved that a further increase in violent conflict had been halted and hoped that a strict military government could establish a new set of rules that would enable an orderly and peaceful construction of a We Collaborate scenario.

I wasn’t sure which of these positions I agreed with. I understood the limitations and dangers of a military government. And I also could understand the junta’s impulse to impose orderly and peaceful collaboration: they were suppressing asserting to enable engaging.

This extreme event gave me the last piece of the puzzle I had been sitting with. I was surprised by what I could now see: a coup d’état is the logical outcome of the way of collaborating that I had been focused on since Mont Fleur. If we embrace harmonious engaging and reject discordant asserting, then we will end up suffocating the social system we are working with. This is what Arenas had been trying to tell me all those years earlier in Guatemala.

In stretch collaboration, we cannot only engage and not assert. We need to find a way to do both.

THERE IS MORE THAN ONE WHOLE

One consequence of the imperative to both engage and assert is that prioritizing “the good of the whole”—whether that whole is our team or our organization or our community—is neither sensible nor legitimate.

All social systems consist of multiple wholes that are parts of larger wholes. Author Arthur Koestler coined the term holon for something that is simultaneously a whole and a part.5 For example, a person is a whole in himself or herself; which is part of a team, which is a whole in itself; which is part of an organization, which is a whole; which is part of a sector; and so on. Each of these wholes has its own needs, interests, and ambitions. Each whole can be part of multiple larger wholes.

There is therefore no such thing as “the whole,” so to claim to be focusing on achieving “the good of the whole” is misleading if not manipulative: it really means “the good of the whole that matters most to me.” If we say that we are prioritizing “the good of the team,” for example, then by implication were are deprioritizing the good of individual members of the team (smaller wholes) and of the organization (a larger whole). In stretch collaboration, we therefore attend not simply to the good of a single whole, but rather to the good of multiple nested and overlapping holons and to the richness and conflict that this inevitably reveals.

The Holonic Structure of Social Systems

In facilitating collaborative teams, I have made this mistake by focusing on the objectives of the team as a whole and thereby implicitly asking participants to leave their individual and organizational objectives at the door. In doing this, I was also conveniently overlooking the fact that the interests of these larger and smaller wholes were identical only for me and perhaps the team leader: we were the only ones who, when we championed the interests of the whole team, were at the same time championing our own interests.

In 2013, almost thirty years after I left Montreal, I moved back there with my wife, Dorothy, to open the Canadian office of Reos Partners. This gave me the opportunity to see my home with fresh eyes. I found this experience delightful and also puzzling: after many years living in other places, I noticed something distinctive in the low-key way that many of the Canadians I worked with approached the challenges we were dealing with, but I didn’t know what to make of it.

The following year, in connection with the upcoming 150th anniversary of Canada’s founding, my colleagues and I conducted interviews with fifty Canadian leaders. We asked each of them what he or she thought it would take for Canadians to succeed in creating a good future.6

During the period when we were conducting interviews, acrimonious and disturbing debates were taking place in Canada and internationally about the place of Muslims in Western societies. One of the people I interviewed was Jean Charest, a former premier of Quebec, who made a striking comment about the political incentives for enemyfying which foreshadowed the US presidential contest two years later:

Demagogues thrive by cultivating insecurity and demonizing certain groups. They emphasize differences rather than the things we have in common. Human nature is such that we remember negatives better than positives. It’s easier to vote against something—or someone—than for it. For politicians, it’s always tempting to pit one group against the other because it works so well and so rapidly.

Then I interviewed Khalil Shariff, the CEO of the Aga Khan Foundation Canada, an organization established by the worldwide spiritual leader of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. Shariff had a thoughtful perspective on Canadian culture that I had never heard before:

In the world as a whole, the notion of homogeneity is quickly disappearing, for two reasons. First, we’re more aware of our individual differences—our “selfness”—than ever before. Second, we have experienced demographic movements that historically were unheard of. These two factors mean that the idea of managing difference and being able to live in some kind of common framework might be fundamental for any society today.

Someone once told me that, for an individual, humility is the king of virtues. What is the king of virtues for a society—the virtue from which all other virtues and capacities stem? I wonder if the capacity for pluralism might be the source from which all others stem.

If you can build the social capacity to deal with pluralism, then you can deal with a host of other questions. The scaffolding of Canadian society—this commitment to pluralism—is invisible to most Canadians. We don’t always understand it explicitly, and we might take it for granted, but it is embedded in us.

Shariff also offered me a personal challenge: “Perhaps this collaborative work you have been doing around the world, which you are so proud of, is not simply an expression of your personal gifts. Perhaps you have been expressing something of the culture you were brought up in.” Canadian culture is not the only one that values pluralism, and Canadians often also express contrary values—for example, in their brutal suppression of indigenous culture. But Shariff was pointing out the crucial value of a culture of pluralism to being able to live and work with contradictory and confounding wholes.

EVERY HOLON HAS TWO DRIVES

The key to being able to work with multiple wholes is being able to work with both power and love. I proposed this framing in my 2010 book Power and Love and continue to find it crucial to making sense of the dynamics of collaboration.

In this book I defined power, following the insightful work of theologian Paul Tillich, as “the drive of everything living to realize itself.”7 The drive of power is manifested in the behavior of asserting. In groups, the power drive produces differentiation (the development of a variety of forms and functions) and individuation (parts operating separately from one another).8

I defined love, also following Tillich, as “the drive towards the unity of the separated.” The drive of love is manifested in the behavior of engaging. In groups, the love drive produces homogenization (the sharing of information and capability) and integration (parts connecting into a whole).

My thesis was that every person and group possesses both of these drives and that it is always a mistake to employ only one. Love and power are not options that we can choose between; they are complementary poles and we must choose both. Here I was elaborating on the point that Martin Luther King Jr., a student of Tillich, made when he said, “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic.”9 I cited many examples in small and large social systems of the twin degeneracies that occur when one of these drives is exercised without the other, and of the generative synthesis that occurs only when they are exercised together.

Every living whole or holon has the drives of love and power. Love, the drive toward unity, reflects a holon’s partness: that it is part of larger wholes. Power, the drive toward self-realization, reflects its wholeness: that it is a whole in itself. Being able to work with both love and power is therefore a prerequisite to being able to work with multiple wholes.

I once talked about this book to a Dutch association of interim managers. These are professionals who do a variety of management jobs, filling temporary gaps in organizations that have special projects or someone on leave or a delay in a new manager taking up his or her position. Their reaction to my thesis was that the need to work with both power and love was obvious: that their whole job as managers was reconciling the drive to self-realization of individual team members with the need to unite the team to achieve its collective self-realization.

I also developed a better understanding of the centrality of power and love for working with social systems as I spent more time with politicians and activists. I was surprised when Antonio Aranibar, who managed a political analysis unit at the United Nations, sponsored the Spanish edition of this book. When I asked him why he thought the book was useful, he said that in his view the essence of politics is aligning the interests of smaller and larger wholes.

Then Betty Sue Flowers suggested that I study how US President Lyndon Johnson had done this aligning. I found a biography of Johnson that contains a riveting account of how he succeeded in enacting landmark civil rights legislation through attending carefully to the interests of individual legislators and thereby harnessing their individual political wholes into a collective one. The biographer writes about a meeting between Johnson and historian Arthur Schlesinger:

Johnson turned to the individual senators, the other forty-eight Democratic senators. “I want you to know the kind of material I have to work with,” he said. Schlesinger was to recall that “he didn’t do all of them, but he did most of them”—in a performance the historian was never to forget. Senator by senator Johnson ran down the list: each man’s strengths and weaknesses, who liked liquor too much, and who liked women, and how he had to know when to reach a senator at his own home and when at his mistress’s, who was controlled by the big power company in his state, and who listened to the public electrification cooperatives, who responded to the union pleas and who to the agricultural lobby instead, and which senator responded to one argument and which senator to the opposite argument. He did brief, but brilliant, imitations; “When he came to Chavez, whose trouble was alcoholism, Johnson imitated Chavez drunk—very funny.”10

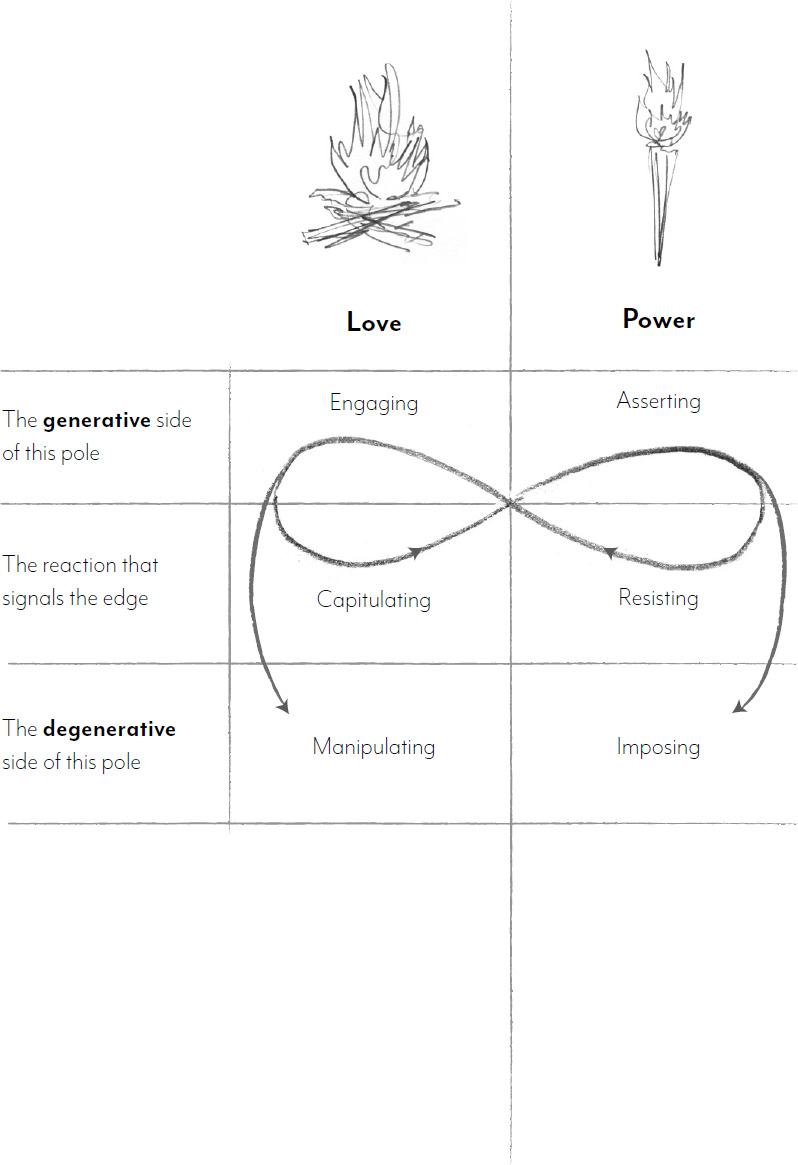

ALTERNATE POWER AND LOVE

After I published Power and Love, I learned that psychologist Barry Johnson had developed a methodology for mapping the relationship between poles such as power and love. Johnson suggests that we must differentiate between problems that can be solved and polarities that cannot be solved but only managed.11 He explains that in a polarity the relationship between two poles is analogous to the relationship between inhaling and exhaling. We cannot choose between inhaling and exhaling: if we only inhaled, we would die of too much carbon dioxide, and if we only exhaled, we would die of too little oxygen. Instead, we must both inhale and exhale, not at the same time but alternately. First we inhale to get oxygen into our blood; then when our cells convert oxygen to carbon dioxide and the carbon dioxide builds up in our blood, we exhale to let it out; then when the oxygen in our blood falls too low, we inhale; and so on. If we are healthy, this involuntary physiological feedback system maintains the necessary alternation between inhaling and exhaling and enables us to live and grow.

Barry Johnson’s mapping enabled me to make sense of my confusing experiences with engaging and asserting. It explained what we need to do to exercise love and power and to work with multiple wholes. I could now see that my early understanding of collaboration—that it meant embracing harmony and rejecting discord—limited its applicability and effectiveness. When I tried to employ this kind of harmony-only collaboration, I usually failed and therefore ended up defaulting to adapting, forcing, or exiting.

When we collaborate, we exercise love and power alternately. First we engage with others. As our engaging continues and intensifies, eventually it produces in them an uncomfortable feeling of fusing and capitulating: of having to subordinate or compromise what matters to them in order to maintain the engagement. This reaction or feeling of discomfort is a signal that they need to switch to asserting or pushing for what matters to them (as Arenas and Suzuki did). But then, as their asserting continues and intensifies, eventually it produces in us an impulse to block or push back or resist. This reaction or feeling is a signal that we need to return to engaging. (In this simple example, I have given each party only one role, but in fact both parties can play both roles.)

We can understand the imperative to alternate between engaging and asserting if we consider what happens if either of these two reactions or edges of discomfort is ignored and overstepped. If we keep asserting and pushing past the other’s attempts to resist, then the result will be our forcing or imposing what matters to us onto them, and thereby defeating or crushing them. In the extreme case, then, employing only asserting produces war and death (this was the possibility of a civil war that some Thais feared during the violent clashes of 2013–2014). This risk, which is widely recognized, is why it is important to notice the feeling of resistance that signals that asserting is going too far and that engaging is required. Engaging when it is needed prevents asserting from becoming degenerative.

Managing the Polarity of Love and Power

On the other hand, if we keep engaging others beyond the point where they feel they are being compromised, then the result will be our manipulating or disempowering them. In the extreme case, then, employing only engaging produces suffocation: the kind of lifelessness that is produced through imposed peace or pacification (this was the possibility of deadening that some Thais feared would be the outcome of the 2014 coup). This risk, which is less recognized, is why it is important to notice the feeling of capitulating that signals that engaging is going too far and that asserting is required. Asserting when it is needed prevents engaging from becoming degenerative.

This less recognized risk of unconstrained engaging is what I had been missing in my post–Mont Fleur embrace of engaging and dialoguing, and rejection of asserting and fighting. Barry Johnson points out that if we are focused above all on the risk of unconstrained asserting (as I was), then we will mistakenly understand engaging to be an ideal rather than only a pole, and thereby produce this opposite pitfall. The mistake I was making was to reject asserting as uncivilized and dangerous, and therefore to push it into the shadows. This didn’t make the asserting disappear; it just drove it underground so that I exercised it less consciously and cleanly.

Psychologist James Hillman points out that many people who, like me, work in “helping professions” make this mistake of rejecting asserting and power. He writes,

Why are the conflicts about power so ruthless—less so in business and politics, where they are an everyday matter, than in the idealistic professions of clergy, medicine, the arts, teaching and nursing? In business and politics, it seems, there is less idealism and more sense of shadow. Power is not repressed but lived with as a daily companion; moreover, it is not declared to be the enemy of love. So long as the notion of power is itself corrupted by a romantic opposition with love, power will indeed corrupt. The corruption begins not in power, but in the ignorance about it.12

When we block asserting, we pervert it and make it degenerative and dangerous.

As Hillman points out, in business and politics the value of asserting (competition and contestation) is commonly accepted, as is the coexistence of asserting and engaging (for example, cooperating to maintain a playing field on which fair competition can take place). But in the field of collaboration, the conventional misunderstanding that you need to engage rather than assert implies that we need to make deliberate efforts to enable generative asserting.

Conventional collaboration focuses on engaging, and that does not make room for asserting, so it becomes ossified and brittle; it settles into a stupor and gets stuck. Stretch collaboration, by contrast, cycles generatively between engaging and asserting, enabling a social system—a family, an organization, a country—to evolve to higher levels.13

When I have given lectures about Power and Love, I have observed that most people are more comfortable either with love and engaging, or with power and asserting. Their preferences are both personal and cultural. They may be able, when they are in low-stress contexts (such as with colleagues and friends), to fluidly employ both of these drives, but when they are in high-stress contexts (such as with opponents and enemies), they default to and get stuck in their comfort zone. Often they recognize the danger of overutilizing their stronger drive and hold back. Some people have said to me, “At work, I feel more comfortable exercising power—I see love as something for home—but as a result, I am often accused of bullying, so I try to rein in my power.” Other people have said, “I feel more comfortable exercising love—I see power as dangerous—but as a result, I often get hurt, so I try to limit my love.” Moreover, often people choose to focus on employing their stronger drive, and they let someone else—their spouse, their business partner, another part of their organization—employ the other one.

Stretch collaboration requires all of us to embrace both love and power. If we constrict—if we weaken our stronger pole or outsource our weaker pole—we will not be successful in collaborating in tough contexts. So we need to do the opposite: practice employing our weaker pole and thereby strengthen it. We need to stretch.

The key to alternating between engaging and asserting is to know when to employ which, so as to keep the cycle generative rather than degenerative. David Culver, the former CEO of Alcan, the Canadian aluminum company, was known as an outstanding manager. When he retired, social innovation researcher Frances Westley asked him for his secret. He answered, “When I feel myself wanting to be compassionate, I try to be tough, and when I feel myself wanting to be tough, I try to be compassionate.” So moving between engaging and asserting requires paying attention to the feedback that signals imbalance (crossing the edge into degeneracy) and then making the corresponding rebalancing move. When our engaging is producing capitulation and therefore at risk of manipulating, it is time to foster asserting. When our asserting is producing resistance and therefore at risk of forcing, it time to foster engaging. The key is not to maintain a position of static balance but to notice and correct dynamic imbalance.

The skill to employing both engaging and asserting is to be alert and courageous enough to be able to make a countervailing move when it is required. In a situation or system that is dominated by engaging, if we begin to assert, then we may be seen as impolite or aggressive. In a situation or system dominated by asserting, if we begin to engage, then we may be seen as weak or disloyal. Going against the tide therefore takes patience: to be able to wait for the moment when the dominant movement is producing frustration, doubt, or fear, and then to make the countervailing move.

The essential practice required for embracing conflict and connection is, then, to attend to how we are employing love and power. When we notice ourselves overemploying love—insisting that the unity and good of the collective whole that we care about must be paramount—then we need to employ power and to live with the conflict, perhaps disturbing, that this will produce. And when we notice ourselves overemploying power—insisting that the expression and interests of the constituent part that we care about must be paramount—then we need to employ love and to live with the collectivism, perhaps constraining, that this will produce. We must keep employing both.