Conclusion

The Future Is Teams

The old workplace is dead. Long live the new workplace!

Slow-moving, top-down bureaucracies are disappearing. Disruptive technologies have increased connectivity and the speed of communication. Work is becoming more flexible—and just plain faster. Organizational boundaries are blurring.

You can read about these changes every day in the business press. For example, The Economist recently proclaimed:1 “It is time to start caring about sharing.” This was just the latest in a string of stories about the arrival of the so-called sharing economy. The term captures an essential aspect of the startups that are replacing service providers like taxi cab companies and hotels. These traditional businesses have been dominated by organizations with generous numbers of full-time employees. But pioneers such as Uber and Airbnb are based on a different model, providing virtual platforms to connect thousands of private individuals who offer services independently and on their own time.

The New Regime

Does anyone have a real job in a real organization anymore? CIO Insight has said that “outsourcing is the new normal.” Inc. has introduced the new “anywhere office” being created by the growth of the flexible workforce. So, you have been warned. You need to pay more attention to new ways of collaborating and teaming. If not, you might find yourself out of the loop and out of work.

Hype or reality? Let's look more closely at the trends.

Will Your World Be Blue, Green, or Orange?2

You should take this question seriously.

Based on a survey of 10,000 employees and 500 human resource professionals around the globe, consulting firm, Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC), created three different scenarios that define how the workplace might evolve by the year 2022. So sit back and imagine: Which future will you inhabit?

In the Blue World, big business dominates. Corporations continue to consolidate and integrate, taking over a larger share of private sector activity. You work in a big multinational where you expect to be employed for decades, with a level of job security that you could not have imagined 10 years ago. While your employment is stable, your work is anything but. In return for this security, you are expected to shift tasks constantly and quickly move up a steep learning curve. You need to be able to develop new working relationships with people who have just joined your organization—through the hiring process or through acquisitions. You also have to stay in sync with colleagues in a network of firms your organization partners with on an ad hoc basis. Far from meaning more top-down management, you find that your company is happy to let you self-manage this shifting network of relationships, as long as you meet the precise and comprehensive set of metrics through which your performance is measured on a daily basis.

In the Green World, social responsibility is more than a buzzword. It is the ticket for doing business. Social media has created radical transparency in global companies, which societal pressures have pushed to become models of environmentally and socially sound practices. CEOs looking to drive “good growth” have spotlighted the HR function, since boosting employee morale and providing a work-life balance are considered top priorities throughout the business world. Your organization has steadily moved toward a flat, fluid structure where you are given more freedom to design your own role and goals to fit your lifestyle and personal passions. This raises a key challenge: in an organizational culture tailored to the needs of individual employees, how do you keep everyone on the same page? You find yourself needing to spend more and more time aligning around collective goals with your teammates and keeping in touch when everyone is able to make their own schedule.

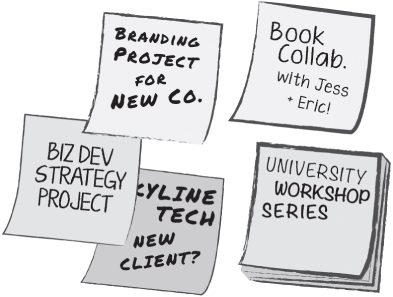

In the Orange World, Silicon Valley–style entrepreneurialism is the rule rather than the exception. The concept of the full-time job is so last century. Networking technologies have made large, permanent organizational structures largely obsolete. Instead, highly specialized independent contractors or small companies come together to collaborate on a project-by-project basis. You might be building a website for one business in the morning and designing logos for another one in the afternoon. While you enjoy the freedom of working when and where you want to, you cringe at the need to gear up every time a new project starts. You have to form a new team with other contractors and entrepreneurs, some of whom you have never worked with before, and build rapport quickly so that you can deliver a product on time and on target. You rarely miss the old multinational you used to work for, but you do notice that you spend a lot more time on managing group dynamics than you ever did as a cubicle rat.

Which world do you think you will live in? Notice that in each case, technological and cultural changes will push you to focus more time and energy on managing team relationships. Whatever the world looks like in 2022, collaboration skills will be at a premium. Formal authority will be even less useful in motivating others. You will be even less able to rely on a unified company culture to keep everyone on the same page. Shifting work arrangements and networks will make it harder for you to fall back on long-term relationships with colleagues to get work done. In any scenario, then, it will take more effort to make shared commitments and stick to them. Good teamwork will be more relevant than ever as saying-doing gaps grow between co-workers and partners who move quickly from one project to the next.

So, how did you answer the question: Will your world be Blue, Green, or Orange? As far as collaboration goes, your answer leads to the same conclusion. You will have to spend more time on teamwork.

Teamwork Trends

Think further about these possibilities, and you might begin to see that the future is even more complex than you first imagined. Major sociocultural and technological trends will likely cause four significant changes in the way you collaborate with your teammates.

Flatter Teams

“Wait, what's a circle again?”

The last time you asked that question was in preschool. But then again, nothing about this group would surprise you right now. As you look around the meeting table, you are having trouble identifying a true team leader, because there is no leader. There is only a facilitator, who explains: “It's what we call teams now. This is the product development circle, remember? So, should we get started talking about our tensions? I have another tactical meeting with the sales circle to get to soon.”

The person to your left pipes up: “I'm processing a tension about the new launch date. It's coming up, and I need more support on working out some of the bugs to hit our deadline.” After the group helps your colleague identify a “lead link” in the research circle who could help her get debugging support, the next person raises his hand. “I have a tension about the kitchen. Nobody takes time to clean up after themselves and I've done the dishes for the past three days straight.”

Circles? Tensions? Lead Links? If you are having trouble keeping up with the jargon, you can appreciate what the employees at companies like Zappos and Medium experienced when they first implemented the new collaborative process called Holacracy.3 Created by programmer Brian Robertson, the system does away with management hierarchies in favor of flat, interconnected teams that assign roles and solve problems on the fly, through regular meetings. Productivity guru David Allen likes its relentless focus on adaptation and rapid decision making. Another appealing aspect: no middle management bottlenecks.

Holacracy is an extreme example of a shift in work relationships away from hierarchy and toward decentralized decision making. More and more businesses are gradually moving in this direction, spurred by a growing body of research and real world case studies demonstrating that empowering employees with more autonomy makes them more motivated and fosters a diversity of perspectives that often leads to better decisions. In Chapter 1, we introduced you to W.L. Gore and Associates, which was an early adopter of the “lattice” organizational structure, where small, interconnected teams of associates replace vertical chains of command. Having employees follow the guidance of mentor-like leaders rather than being supervised by managers has landed Gore on Fortune magazine's “100 Best Companies to Work For” list for the past three decades.

At IDEO, employees are “invited” to attend meetings.4 When they do, they expect the best idea in the room will win whether it comes from a new designer, or the CEO. Vice president Tom Kelley believes that this democratic atmosphere and the lack of a strict management structure are crucial to spurring the creativity his teams need to keep their innovation edge: “Innovation requires that we draw upon every single person in our organization for ideas. However, if there's a strict hierarchical system, people would have a hard time expressing their opinions since employees tend to want to please their superiors. It's important to flatten the organization and build a culture where everyone's idea is respected and where mistakes are allowed to happen.”

Never one to shy away from walking the walk, Kelley has been mentored by employees 15 years his junior so he can get a different generational perspective on his work.

At the productivity software company Basecamp,5 a rotating management system means each person will have to step into a leadership role at some point. This keeps team rapport high as it eliminates the management-labor tensions that create barriers to collaboration in many businesses.

Despite the benefits of the trend toward flatter teams, it also raises a host of new challenges. For example, Basecamp co-founder Jason Fried had to take an unusual step for his company when an employee complained about wanting new managerial responsibilities: he let her go—and this in spite of her being a top performer. She needed vertical mobility that the company could not provide. Misalignments around developmental goals such as this one are a key issue raised by flattened structures.

At Zappos, many employees value the high level of input they have under Holacracy. Under this system, even a shuttle bus driver was able to make it company policy to keep trash out of the vehicle. On the other hand, employees find that they spend more time and energy figuring out roles that can shift frequently as tasks are reallocated on the fly. At Gore, the model of having informal guides instead of managers means policy enforcement can be tough, since employees need to be self-motivated to adhere to company norms.

In sum, the trend toward more autonomy in teams has the potential to unlock vast reservoirs of employee energy and creativity, but it also creates a freewheeling environment in which it can be tougher to have a structured discussion about team commitments.

Looser Structure

It feels like a large-scale version of the garage where Jobs and Wozniak launched Apple. But actually, it is a co-working office. Mike looks out the windows of his conference room at the other independent designers and consultants whose workspaces are connected like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Professionals are chatting on iPhones with clients in all corners of the world, their conversations blending with the sounds of indie rock streaming over the wireless speakers hanging over his head.

Mike turns back to his colleague, a marketing specialist, who is soliciting ideas on a new company name from three entrepreneurs involved in a rebranding process. The specialist is wearing a faded black t-shirt and tan chinos, mirroring the laid-back fashion sense of his clients. After Mike wraps up this meeting, he will don a button-down shirt and a blazer for a presentation downtown at a corporate office. He will make sure to get there a little early to touch base with the representatives of the marketing firm that contracted with him to design logos for their client.

Like the other independent professionals with whom he shares a co-working space, Mike values the independence of being a freelancer. But he sometimes feels far from free, because he spends so much of his time managing relationships with the different partners and companies in his network.

Mike represents a significant trend: the rise of contingent labor. By 2020, freelancers and temps are expected to make up 20 percent of the workforce,6 up from about 15 percent today. While temp agencies have provided staffing solutions since their rise in the 1950s, companies like Taskrabbit are reducing the role of the middleman and connecting companies directly with freelancers. These modern-day temps run errands and perform quick services, but a growing number of businesses like MBA and Company are offering high-level consulting talent to staff entire strategy and operations projects.

This trend has been driven in part by a weaker economy in which employers are more able to maintain flexible workforces to raise efficiency and keep overhead low. But workers are also driving the trend: millennials tend to value the independence and flexibility of freelancing. Ironically, as workers become more independent, social networks become denser and teams become more ubiquitous.

Wider Connections

Your alarm rings at 2:45 a.m. You shake yourself awake and shuffle down the hall to your home office. Luckily, since the call with your Shanghai colleagues is audio only, you can wait to get dressed. The rest of your day's schedule will be spent on calls and videoconferences with other partners and clients in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, and Atlanta. Your work has become unmoored from geography. You can do your work anywhere, and travel whenever a face-to-face meeting or facilitation is really necessary.

In this globalized, highly connected world, as many as 50 million Americans—40 percent of the workforce—work from home at least part of the time.7 Approximately 48 percent of all managers spend half of their week working remotely (from home or on the road). Since co-location is rarely required to get work done, it makes sense not to commute daily to a building filled with offices and cubicles where everyone communicates through email and phone anyway. Proponents of telecommuting tout the cost savings to companies that do not need large office spaces to support their workforce.

But robust telecommuting arrangements have a dark side, too. Always open on your desktop are two windows: your email that you are constantly refreshing, and your company's chat application. Since you work mostly from home and on the road, you feel a need to be always available and visible to the rest of your team members.

Another drawback is the pressure to put in “virtual face time.” A study conducted by Boston University professor Erin Reid8 revealed a major division among the staff at a global consulting firm. Some were clearly seen as being less committed and lower achievers whereas others were viewed as star performers. The difference? Consultants in the first group had formally requested flexible schedules to take care of their families and handle other affairs at home. The “star performers” asked for no time off, but they actually worked fewer hours—50 or 60 rather than the standard 80. They just found ways to make it seem like they were always working. For example, they would strategically send an email or two at odd hours. Those who were known to be working from home were only perceived to be less productive than their colleagues who never bothered to tell anyone about the arrangement.

Other studies reveal that those who work remotely are often even more productive than their office-bound counterparts.9 Research conducted by the Chinese travel website Ctrip showed that employees working from home made 13.5 percent more calls—almost a whole extra workday's worth of productivity per week.

As wide teams become the norm, you will need to learn how to contend with a few distinctive challenges: the challenge of working and being “virtually visible” at all hours; the challenge of conveying the impression when you work remotely that you are busy and productive, even though you are actually more busy and productive than your co-workers in the office; and, of course, the challenge of teaming with geographically dispersed co-workers who are on multiple teams in multiple time zones.

Faster Work

“Anything—a misremembered line, an extra step taken,10 a camera operator stumbling on a stair or veering off course or out of focus—could blow a take, rendering the first several minutes unusable even if they had been perfect. You had to be word-perfect, you had to be on script, and you literally had to count your paces down to the number of steps you needed to take before turning a corner.”

So Michael Keaton described the incredibly stressful experience of making Birdman. It was filmed to look like one long, continuous shot. Actors did 10- to 12-minute takes that had to flow perfectly to be usable. Under Alejandro González Iñárritu's direction, a team of actors and craftsmen came together to shoot this award-winning film (four Academy Awards, including best picture in 2015) in fewer than 30 days.

This is the so-called Hollywood model of working. Get used to it. Here is what you can expect: an opportunity is identified and a team is assembled that works together only as long as it takes to finish a project. You might collaborate with some people on multiple assignments, but on each one you have to re-form a team only to dissolve it again a few weeks later.

In more and more businesses, the Hollywood model is applied to fixed-term projects that are large and complex, requiring a number of differentiated, complementary skill sets. The last hundred years or so of enterprise have been based on the manufacturing model. But no longer. “More of us will see our working lives structured around short-term,11 project-based teams, rather than long-term, open-ended jobs,” NPR's Adam Davidson predicts.

As work becomes faster, Hollywood style, your ability to be a flexible, committed, high-performing teammate will determine whether you work at all.

Your Toolbox for the Hyper-Collaborative World

Now you have seen the future of teamwork: flatter, looser, wider, faster. Are you prepared? Not to worry. We know you are prepared, because you know how to apply the 3×3 Framework (Figure C.1).

A quick review shows that the 3×3 Framework will help you:

Establish Commitments

Every team—now and in the future—needs to make commitments in the form of goals, roles, and norms. Team members will need to be honest with themselves and each other about their abilities and their competing commitments. One of your team's greatest assets will be a high-performing culture, which promotes the adaptability and flexibility needed in the hyper-collaborative physical and virtual worlds.

Check Alignment

Teams have always drifted from their initial commitments. The pushes and pulls that cause drift will only continue to multiply as work becomes flatter, looser, wider, and faster. Fortunately, teammates will help get projects back on course when they have been properly prepared to identify and address misalignments.

Close the Saying-Doing Gap

Successful teams are disciplined about developing habits that support their commitments. In the early twentieth century, William James said that habits are the great flywheel of society. That same flywheel will continue powering the age of digital communication, wide teams, and project-based work.

Passion and Performance through Process

But wait—you are already living in the hypercollaborative world. As William Gibson, the cyperpunk novelist, once said,12 “The future is already here. It's just not evenly distributed yet.”

Entire organizations are structured like a high-performing team that works flatter, looser, wider, and faster. Just consider Salesforce.com. Starting with a customer resource management (CRM) product that was launched in 1999, Salesforce.com has grown to become one of the most highly valued cloud computing companies in the world. Somehow, as this company grew from a startup to an organization of 10,000 employees and a market capitalization of over $50 billion, it has been able to maintain a strong culture of innovation. Under the leadership of founder Mark Benioff, it has avoided the usual pitfalls of startup success: a ballooning bureaucracy, limited flexibility, and flagging passion.

Salesforce.com has retained its startup energy by adopting the SCRUM technique of teaming. SCRUM was originally developed in the 1980s by game developers, Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka, to increase speed and agility on product development teams. It values innovation and shared responsibility among all members of a cross-functional team. Management gurus Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland13 adapted the idea to general business practices, and it has steadily gained popularity in many organizations. To truly and successfully implement SCRUM requires a mindset in which managers are enablers rather than enforcers. Workers also have to see themselves differently: self-organizing and accountable rather than simply following the lead of their bosses.

An over-the-top commitment to clear structure supports flexibility. Benioff's V2MOM system14 (vision, values, methods, obstacles, and measures) maps out every product and to-do in the company, from large product launches to the weekly office grocery list. Employees have personal to-do lists that they use to track their progress quarterly. For projects that are high-priority, an internal CEO is assigned, and given as many resources as necessary. This system exemplifies the 3×3 principles: it clearly lays out commitments, creates a process for check-ins, and helps to minimize the saying-doing gap. Even further, it helps ignites passion among workers.

At an annual internal job fair, employees are encouraged to shop around for opportunities. No one should feel “stuck,” or locked in to just one job. “Any job you do long enough, it starts to get a bit boring, and I was told to explore,” said Leyla Seka, a manager of Salesforce's App Exchange.15 Retaining workers who are excited and passionate has helped to supercharge the company. As of 2015, Salesforce.com had won Forbes' Most Innovative Company Award three years running. Other achievements: some of the highest customer satisfaction ratings in the industry and a sector-leading stock price.

Benioff has already ushered his Salesforce.com teams into the hyper-collaborative world. With the tools in this book, you can bring your team there, too.

So What About You?

Let's end by imagining how you might take a small step toward putting the 3×3 Framework into action. And since the process is iterative—not a linear, one-time event—let's loop back to where we started at the beginning of this book…

…With the sweat still dripping down your face. Your hands are cramping from pulling on the rope with all your might. You look up and the boulder attached to the rope is still there, still stubbornly in place. Your fellow team members begin piling on to join you. After all, as soon as you haul the rock 30 feet, you all get to leave the company retreat and head to a celebratory team dinner.

Only this time you stop everyone from blindly grabbing the rope and yanking. Perplexed, your teammates gather around as you ask what the team's goal should be. “Obviously to get the rock across the finish line,” someone offers. But you keep pressing. When you start asking about the roles and norms that will best achieve that goal, you see ah-ha looks appearing.

Rather than having everyone pull at random, you decide to yank the rope in unison. You put the strongest team members closest to the rock and assign the most outgoing team member to be the motivator, going up and down the line making sure everyone is engaged.

Energized, the team begins pulling. But after a few seconds, the motivator realizes that the rock could be moving faster. He suggests corrections to the team's pulling technique that create better leverage. After the team makes the change, the rock begins moving quickly and steadily forward. Once it crosses the mark, everyone cheers, having conquered the social loafing barrier that had been plaguing the team.

“Maybe teams can work after all,” you say to yourself as you wipe the sweat off your brow. You join the others as they walk off the field and head to dinner. It feels good to know that you are finally, fully a…committed team.