7

PRESENTATIONS: PLANNING AND PREPARING

Knowing how to give good presentations is essential to achieving success in your organisation and career. That may not seem apparent if you just started in an entry-level position in a company, and most of the presentations you’ve made thus far were in school. But what you learned in school will help as you advance in an organisation and find yourself making more presentations to broader audiences. CFOs are in great demand as presenters. According to CFO Magazine, ‘CFOs increasingly find themselves confronting eager audiences, as boards, Wall Street, and other constituencies call upon them for greater insight into corporate performance and strategy.’1

This chapter and the one that follows focus on presentations: their purpose, elements and structure, and how to use presentations to communicate effectively. In this chapter, we will discuss how to plan and outline your presentation. The next chapter will focus on designing and delivering slide presentations. Appendix E distils the considerations presented in these two chapters into a convenient checklist form.

So, what is a presentation? Simply put, it’s showing and explaining something to an audience. What you present could be an idea, a solution, a service, a product, a project or something else. The audience could be an individual, such as your boss, a small group, such as members of your team, or hundreds of people.

There are many reasons for presentations, but they can be distilled into two main categories. The first reason is to inform: You provide the audience with new information or new insights. The second reason is to persuade: You try to convince the audience to support a plan or a cause, change their minds about an issue, or take action.

Presentations can be formal or informal. You could make a 20-minute presentation about a new product to your company’s top executives. Or you could have three minutes to explain your product to a busy senior executive who missed your presentation and is hurrying out to a meeting. You could be called into a meeting on a moment’s notice and asked to answer a question about the product. Whether you have 20 minutes to deliver a presentation or only a few minutes or whether you’re presenting to top executives, your supervisor, or your colleagues, you have to be prepared, and that begins with planning.

PLANNING

In this book, an entire chapter is dedicated to planning and outlining before writing a report. Similarly, planning your presentation is an important step. This section summarises the questions you should ask while planning your presentation:

First, determine your purpose. Why are you making the presentation? Is it to inform or educate your audience about a topic, such as the business application of an accounting rule? Are you trying to convince your audience to support your plan to reduce costs, or change from opposition to support of a merger, or to buy a company product?

Next, identify the topic(s) of your presentation. Your topic could be about any aspect of a company’s business: strategic planning, operations, finance, accounting, marketing, sales, human resources, logistics, research and development, education and training, and more. It could be about economic, social or other issues. Once you decide on your topic and learn about your audience, you can develop the key message for your presentation.

To determine your audience, think back to the discussion of audiences in chapter 5. Members of your audience might consist of people you work with every day; other people in your organisation, such as your supervisor, a business manager or the CFO; or people outside your company, such as customers or clients, investors, consultants, and others. It might include a mix of people from inside and outside your organisation and people from other countries. Your audience’s familiarity with your topic might vary.

Ascertaining the needs and wants of your audience should be a top priority as you plan. ‘During the planning phase of your presentation, always remember that it’s not about you. It’s about them,’ writes communications coach Carmine Gallo. ‘The listeners in your audience are asking themselves one question—“Why should I care?” Answering that question right out of the gate will keep your readers engaged.’2

Your presentation must be attuned to the needs, interests and concerns of people in your audience. To align your presentation with their interests, you must understand your audience first. What are their interests? Likes and dislikes? What motivates them? How are they likely to receive your presentation—with enthusiasm, indifference or hostility? Who are the influencers in your audience? These are the people who influence or make important decisions, and you will need their support for your ideas and initiatives. What can you say that will resonate with them?

Learning about your audience may require you to do some research. Assume you work for a large company, and you are speaking with managers across the organisation about development of an important product that will involve every manager and department. You want to know what questions they might ask. You could preview your presentation for one or two managers and solicit their questions. You might talk about your presentation with others in your organisation and get their questions. As a result of your research, you could decide to revise your presentation to address some of the questions, and you will be better prepared to answer others.

Some speakers, especially if they are new to making presentations, may be a little intimidated by the audience. An audience can be sceptical, ask tough questions, and maybe call you out if you make a mistake in the information you present. But the audience is on your side. ‘In the real world, the average attendee at a conference or presentation has no interest in judging or critiquing you,’ says author and speaker Justin Locke.3 ‘They all have one single thought uppermost in their mind and that thought is, “please, please, don’t let this presenter bore me to death for the next hour.”... Far from preparing to disdainfully judge you, the majority of the people in the audience are rooting for you like mad.’

Your last step in planning should be to investigate what the circumstances of your presentation will be. This includes the number of people in the audience, the size of the meeting room, the time of the presentation, the seating arrangements, your position in relation to the audience, the lighting and the comfort level of the room. If you are speaking to a large audience of several hundred people, you may have more of a challenge holding their interest than if you were speaking with ten people in a more intimate setting. Audiences may be more attentive in the morning than in the afternoon or evening. Uncomfortable chairs or too much or too little lighting may distract audiences.

OUTLINING YOUR PRESENTATION

Storyboard: A Visual Outline

When writing a report or other document, you begin by writing an outline. With a presentation, you start with a visual outline: a storyboard.

Although you can use PowerPoint, Keynote, Prezi or other software tools for this purpose, some presentation designers and consultants recommend you create an outline the old-fashioned way: by hand, using a pen or pencil and paper or a whiteboard. The reasoning is that the physical act of writing and sketching stimulates creative thinking, the free flow of ideas and a fresh approach to looking at problems or issues without working within the restrictions of software templates. In her book, slide:ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations, Nancy Duarte notes that much of today’s communication has an intangible quality. ‘Services, software, causes, thought leadership, change management, company vision—they’re often more conceptual than concrete, more ephemeral than firm. And there’s nothing wrong with that,’ writes Duarte.4 However, writing by hand can help to express your ideas so that they feel tangible and able to be acted upon.

You can jot ideas and sketch rough illustrations on a blank sheet of unlined paper, with one idea for each sheet. Or, if you prefer, you can write and illustrate on a whiteboard. Another option is to sketch on sticky notes and stick them to a whiteboard, a wall, a mirror or whatever else you want to use, as shown in figure 7-1. You can easily rearrange them as you organise your presentation, and their size limits the number of words you can write on a single note. This helps you to concentrate on the idea, not the wording.

At this point in planning your presentation, your aim is to sketch on paper or a whiteboard as many ideas as you can. The operative word is ‘many.’ Don’t quit after jotting down a few ideas, keep going. Don’t stop to try to organise your ideas. This is comparable to creating an outline for a written report or other document by brainstorming, mind mapping or free writing, as described in chapter 5. When you feel you truly have run out of new ideas, take a break and do something else or just relax. Time away from preparing your outline can give you a fresh perspective.

When you return to your outline with fresh eyes, study the paper, whiteboard or sticky notes containing your ideas and illustrations. Which ideas should you drop, which should you keep? Do any new ideas occur to you? Consider asking colleagues, friends and others to look at your ideas. They may offer new insights or raise new questions about what ideas to use. Get rid of papers or sticky notes containing ideas that you won’t use, or file them for possible future use. Draw an ‘X’ through or erase ideas on your whiteboard. Through this process, you can identify, organise and develop the ideas that will form your presentation and start thinking about your key message.

Figure 7-1: Wall With Sticky Notes Outlining a Presentation

Source: Flickr (Credit: Kelsey Ruger). Whitney Quesenbery and Kevin Brooks, Storytelling for User Experience, (New York: Rosenfeld Media, 2010) www.rosenfeldmedia.com/books/storytelling/

Developing Your Key Message

In preparing your storyboard, think about your key message. Duarte writes, ‘Your primary filter should be what I call your big idea: the one key message you must communicate. Everything in your presentation should support that message.’5 One approach to developing your key message is to adapt a practice from journalism. To get started writing a story, some journalists write the headline first. This gets them thinking about the key message and how to capture it in a few words.

You could follow their example and write a headline for your presentation that captures your key message. It should be concise, specific and offer a benefit. In his book about Apple CEO Steve Jobs’ presentation secrets, Carmine Gallo suggests headlines should be no more than 140 characters, the Twitter maximum. For example, in a 2007 presentation, Jobs introduced the iPhone to the world with the simple but powerful phrase, ‘Apple Reinvents the Phone.’

Audience Memory Curve

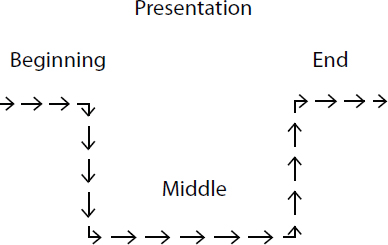

Now that you’ve developed your key message, where should you place it in your presentation? A wellestablished principle, the audience memory curve, says that people are most likely to remember what was said at the beginning and the end of a presentation. So, state your key message at the beginning of the presentation, build upon it in the middle and reinforce it at the end (see figure 7-2 for an illustration of the audience memory curve). If there is one thing people should take from your presentation, it’s that message.

Figure 7-2: Audience Memory Curve

Introduction

Once you know your key message, you can decide on an introduction. Your audience may look alert and attentive at the start, but don’t fool yourself. You have only a few minutes to engage people, otherwise, your audience will lose interest, so you need an introduction that will immediately get their attention. The following are some verbal examples of ways to immediately captivate your audience:

Explain why you’re givingthepresentation. ‘I’m here to explain how the software programme our company developed can help customers to better manage their inventories.’

Define a problem. ‘Our company’s electricity costs increased faster than expected in the fourth quarter. Here are five steps we can take to control costs.’

Identify an opportunity. ‘We have an opportunity to enter a new market: Brazil. Should we take advantage of the opportunity and enter the market? Today I will discuss why we have that opportunity and suggest a decision-making process for determining whether we should enter the market.’

Make an attention-getting statement. ‘Over the next five years, one out of every five people in our company will retire. That means 5,000 people will leave our workforce. That’s more than have retired in the past ten years. How are we going to recruit and train people fast enough to replace our growing number of retirees?’

Share a personal experience. ‘For the past few years, I’ve been working as a volunteer tutor in a community college programme. I’ve been tutoring an immigrant from China. When he arrived, he did not speak English, and he had no job skills. Now, he reads and writes English, he received his general equivalency diploma for secondary school, he’s studying computer programming, and he plans to apply for citizenship. Today I want to talk about giving back to your community by working as a volunteer, the personal satisfaction you can get from volunteering and how you can learn more about volunteering.’

Share a quotation. ‘Henry Ford said, “Obstacles are the frightful things you see when you take your eyes off your goal.” I’m here today to talk about goals, specifically, about three goals for our company: to increase sales by 10% a year, every year; increase profits by 7% a year; and increase our reinvestment in the company—in new factories, plants, and equipment and in hiring and training people—by 5% a year.’

Share an anecdote. ‘When a tidal wave hits, basically, three scenarios follow: Some people feel they have seen it all before, and they do nothing...and drown. Others will save themselves and evacuate (and when it’s over, seldom have homes to return to). Finally, there are those who survive and say, “This is a tidal wave. I better learn to surf tidal waves.” Tonight, I’d like to talk about how our business needs to learn to surf tidal waves.’6

Ask a rhetorical question. Ask a question in which the answer is implied: ‘If our cash flow continues to deteriorate, can we survive as a company?’

Ask a real question. ‘Our company has grown into the dominant organisation in our industry and markets in the United States. So, has the time come to expand globally? It has, and here’s why.’

Surprise your audience. ‘Thanks to you, our magnificent employees, our company has made a terrific comeback this year. And to show management’s appreciation for your hard work and dedication, we are reinstituting the performance bonus programme that was cancelled two years ago.’

Start with some humour. You could relate a humourous anecdote, tell a funny story that you heard or read, or tell a joke. But there are risks in joking. The audience might not be amused. Instead of laugher, there is an uncomfortable silence. If you’re telling a joke, some people may already know the punch line. Or, they may not appreciate your type of humour. If you want to start with humourous remarks, you might try them out first on some colleagues or friends.

Give a demonstration. You could do a demonstration, for example, of a new product. Show the product on a screen and explain its features and benefits. But the product might still seem remote to the audience. They can see it, but they can’t get close to it, touch it, handle it, or examine it. A solution might be to pass samples of the product around the room. At the introduction of its MacBook line of notebook computers in 2008, Steve Jobs discussed the design of a new aluminium frame that enabled production of lighter, thinner, more durable notebooks. Staff members passed out samples of the frames.7

Of course, a live demonstration assumes the product can be easily shown and handled. A demo of your company’s new rocket for launching satellites wouldn’t work in a conference room—for obvious reasons. Maybe you could take the audience to a launching pad for a demo. That would certainly get their attention.

Which introduction should you use? As always, this depends on your audience. If you are making a presentation to top executives or business line managers, they’ll want to know immediately why you’re doing the presentation and why they should care. So, you could start with the reason for your presentation. Alternatively, you could start by defining a problem, stating a solution and then going into how to achieve the solution.

If you start with a quotation, anecdote or rhetorical question, segue quickly to the purpose of your presentation and why your audience should be interested. For example, in the preceding anecdote about the tidal wave, the speaker quickly goes on to tell the audience how to ‘surf the tidal wave,’ or how to manage through a crisis.

Don’t wait until you have to make a presentation to start thinking about ideas for an introduction. When you come across an inspiring quote or relevant anecdote, file them away for future use. You can find ideas in many sources: books, articles, reports, blogs and other web content, the media and more. Some sources are listed in the bibliography at the end of this book.

Transitions

Build strong transitions between your introduction and your content, between the major elements of your content, and between your content and closing. They break the presentation into discrete but interconnected parts, making it easier for your audience to follow along as you move through your presentation. Box 7-1 shows where you can insert transitions during outlining to remind yourself to connect each piece of your content to the next.

Box 7-1: Presentation Outline With Transitions

| Introduction |

| Transition |

| Content |

| Theme (Key message) |

| Transition |

| Supporting argument #1 |

| Transition |

| Supporting argument #2 |

| Transition |

| Supporting argument #3 |

| Transition |

| Conclusion |

You can use a transition to look back in your presentation and then look forward. Let’s consider an example. In the list of possible introductions in the previous section, the second point was this:

Our company’s electricity costs increased faster than expected in the fourth quarter. Here are five steps we can take to control costs.

The transition for this introduction is the second sentence. This transition can be carried throughout the rest of the presentation. After introducing the first step, discussing it, summarising it, and then looking back and then forward, the speaker’s next transition could be, ‘That was the first of my five suggested steps to control costs. Now, let’s move on to the second step.’ The speaker could use the same transition for each step. After discussing the five steps, the speaker might say, ‘To summarise, these are the five steps I’ve suggested to control costs,’ and then transition to the conclusion.

Guidelines for Content

Now that you’ve decided on your introduction, you can gather and outline your content. Recall that presentations generally have two purposes: to inform or persuade. Depending on the purpose of your presentation, you may choose to alter the content of your presentation to support your purpose.

When your purpose is to present information, you provide the information, explain why you are providing it and why the audience should be interested. For example, when speaking to a group of managers about a new system for cost accounting that the company is introducing, you could briefly explain the system, why it was introduced, how it will help managers in accounting for costs in their departments or business lines and how managers can help with managing the system.

When your purpose is to persuade, make your case for why the audience should support your point of view, commit to a plan, or take a course of action. Begin with your key message, support it with arguments, and back your arguments with statistics, examples, anecdotes, analogies and other support.

The advice in the rest of this section will help you to arrange your content to not only convey your information but also keep your audience interested.

Tell a Story

Telling a story through your presentation can be an unexpected but effective method for presenting your content. People can be captivated by a story, and no wonder. Humans have been telling and listening to stories for millions of years. Stories are our way of remembering, sharing and finding meaning in experiences. ‘Everybody—regardless of age, race or gender—likes to listen to stories,’8 writes Paul Smith, director of Consumer & Communications Research at the Procter & Gamble Company. Stories inspire people. Stories are memorable. Audiences are more likely to remember facts if they are woven into a story than if they are simply presented as facts. Stories are persuasive. An audience might resist a speaker who tells them what to do, but they could be won over with a story.

Executives are accustomed to using conventional language to persuade, building their case with facts, statistics and quotes from authorities. Even if they succeed, however, they’ve done so only on an intellectual basis, and people are not inspired to act by reason alone. Famed American screenwriting lecturer and coach Robert McKee discusses how storytelling can be a more persuasive technique than using rhetoric.9

The other way to persuade people—and ultimately a much more powerful way [than rhetoric]—is by uniting an idea with an emotion. The best way to do that is by telling a compelling story. In a story, you not only weave a lot of information into the telling but you also arouse your listener’s emotions and energy. Persuading with a story is hard. Any intelligent person can sit down and make lists. It takes rationality but little creativity to design an argument using conventional rhetoric. But it demands vivid insight and story telling skill to present an idea that packs enough emotional power to be memorable. If you can harness imagination and the principles of a well-told story, then you get people rising to their feet amid thunderous applause instead of yawning and ignoring you.

By turning a presentation into a story, you greatly increase the chances that people will remember what you say, observes Nick Morgan, CEO of Public Words. According to Morgan, a CEO who gives rational arguments for increasing profits with lots of numerical support will only end up boring his audience. Furthermore, he or she is not likely to inspire employees to work to make those profits happen. ‘If, on the other hand, he links our efforts (somehow) to finding the Holy Grail, or beating the Evil Empire, ...we’re far more likely to remember—and act—upon what he’s saying,’ says Morgan.10

Big picture stories, like a company that was almost destroyed by the global recession and financial crisis managing to make a comeback, lend themselves to storytelling. But how can you tell stories about less dramatic things like getting inventories under control and reducing inventory costs?

In this case, you could tell stories about the ramifications of inadequate inventory control on people throughout the organisation, for example:

The business line manager who cannot get the materials necessary to keep production on schedule

The logistics manager who is trying to find space for an excess of inventory

The failure of a team to complete a project on schedule because of a lack of parts and equipment

The cost accountant who is trying to calculate the costs to the company of excess inventory

As you continue your presentation, you could describe the success of the CFO and financial managers in developing and implementing a plan to manage inventory more efficiently, thereby reducing costs and inefficiencies.

Creating a story will help your audience connect to your content, especially if your purpose is to persuade. Storytelling can be a useful technique if you need to put your numbers in context, as discussed in the next section.

Put Your Numbers in Context

Stephen Few, author of Show Me the Numbers, says, ‘The information that’s stored in our databases and spreadsheets cannot speak for itself. It has important stories to tell and only we can give them a voice.’11 He describes this storytelling process as the ‘statistical narrative.’ When assembling a statistical narrative, one of the most important characteristics to address is context. A story cannot be told through numbers alone. Even if the numbers measure something important, they need to be presented in context.

Few contends that appropriate comparisons are a vital way to provide context for numbers. Examples of providing context include comparing the present to the past, examining targets and forecasts, looking at other things in the same category, such as competitors’ products, and discussing norms and averages.

Numbers should be concrete, relevant and in context:

XYZ company reports its profits increased 15% or $20 million in the current year versus last year. Profits increased because the company cut costs 5% and increased revenue 10%.

This statement is concrete and relevant to the company’s investors and management, but there’s no context. Add statements that provide context so that the reader can interpret the meaning of numbers. Compare the previous statement to the following one that gives more context.

XYZ company reports its profits increased 15% or $20 million in the current year versus last year. The profits of XYZ’s closest competitor increased only 5% or $5 million during the same period. XYZ is now the most profitable company in its industry. Of the $20 million profit, XYZ plans to reinvest half back into the company, use $5 million to pay down its debt and hold the remaining $5 million in a cash reserve.

Keep It Simple

If there’s one overarching reason why presentations aren’t effective at communicating content it’s because they are unnecessarily complex. Keep your presentation simple. It’s a rule not only for presentations but also for communication generally. David Duncan, president of Denihan Hospitality Group, echoes this sentiment in explaining his communication philosophy: ‘Keep communication simple. Some people start with the details and soon get lost in complex technical discussions.’ (See interview 12 with Duncan in appendix A.)

One way to keep your presentation simple is to separate the body of your presentation—your content—into three sections that develop your core message or theme. Why three? The rule of three is widely used in writing, storytelling, movies, books, cultures, history and organisations. Studies have shown that people have difficulty holding more than three things in short term memory, but they will remember units of three.12 Julius Caesar said ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ Thomas Jefferson wrote of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. In 2011, Steve Jobs introduced the iPad2 as ‘thinner, lighter, and faster’ than the original.

Sometimes, it may make sense to have more than three sections of content. However, audiences could feel overwhelmed and start to tune out if you try to squeeze more sections and more details into a presentation. Also, audiences could grow impatient and sceptical. Instead of focusing on the information you are presenting, they will wonder why you can’t communicate your ideas more efficiently or if you really understand your topic.

Deliver a Presentation, Not a Document

In making a presentation, you are speaking directly to your audience, which is entirely different from writing a report and sending it to people. But some presentations look and sound like reports. The presenter takes a page of a document, plugs the information into in a slide, puts the slide on the screen and reads the slide. Garr Reynolds, author of Presentation Zen, a book about presentation design and delivery, calls this type of presentation a ‘slideument (slide + document).’ The audience is struggling to simultaneously read a presenter’s ‘slideuements’ and listen to the presenter. Before long, the audience gets frustrated and stops paying attention to the speaker and the slides.

Corporate presentation coach Jerry Weissman agrees that most slides tend to hinder rather than help presenters. ‘The all-too-common complexity of the slides forces presenters either to skim over them or, in the worst case, read them verbatim.’13 Weissman says he isn’t recommending that presenters eliminate slides completely. He suggests designing slides that are simple and serve only to support the narrative of your presentation and do not distract from the presenter. See the section on designing effective slides later in the next chapter for tips on how to avoid creating overly complex, distracting slides.

Slides are one of the most common visual aids used in presentations, but whether you use slides, a flip chart or a whiteboard, your visuals should illustrate, illuminate and amplify your ideas. A single image or a line of text on a screen can communicate your idea with more power and eloquence than a screen full of words. Imaging is particularly effective with people who are oriented to learning and understanding through visual images. Let your visuals serve only as visuals and do not force them to be your entire presentation. Every element of your presentation should work together to reinforce your key message. By speaking, you connect with those in the audience who are attuned to learning by listening. If you want your audience to read a document supporting your presentation, it should be separate and not crammed into your slides.

Deliver a Meaningful Presentation

It seems obvious that you would want you presentation to be meaningful, but if you get engrossed in discussing facts and figures and preoccupied with your visuals, you may forget about why you’re doing your presentation in the first place. There’s also the risk you’ll deliver a presentation that has little, if any, meaning for the audience—it could leave your audience confused and unenlightened. In planning your presentation, ask for a reality check from colleagues or others. Do they think your presentation will have value for your audience?

Establish Credibility With Your Audience

Whether your reputation precedes you, or you’re an unknown quantity, you must establish credibility with your audience. In making an argument, present both sides and explain the reasons for your point of view. Demonstrate your mastery of detail. Back your presentation with solid research—look online for articles, studies, reports, statistics, web content and other sources of information. Talk to people in your company who are knowledgeable about the subject of your presentation and can offer observations and insights. Talk to people at trade groups, universities and other organisations about your topic.

Manage Your Time

Remember, based on the audience memory curve shown in figure 7-2, audience interest is lower in the middle of your presentation when you are delivering your content than at the beginning and the end. So, how can you keep the audience’s attention? One way is to manage the time for your presentation. Can you complete your presentation in ten minutes? Or twenty minutes?

Sometimes, you may need to make a longer presentation because of the nature of the content or because you’ve been asked to make a 30-minute presentation. So, how do you keep your audience engaged? With a half-hour presentation, you might organise the presentation in three 10-minute segments. At the first 10-minute mark, introduce a new idea, concept or question, or make a challenging statement to reengage your audience, and then proceed to develop your idea or question for 10 minutes. At the second 10-minute mark, repeat the process. Use strong transitions to weave the sections together into a coherent whole.

Ensure Your Information Is Accurate

In the interest of providing your audience with credible information—and maintaining your credibility with your audience—make absolutely certain your information is accurate. This is a particular concern when you are presenting technical information, such as accounting and tax information, and your audience comprises other accounting professionals—or even customers and clients. In these circumstances, if you present inaccurate information, you can be certain someone will correct you, which is as unpleasant as it is embarrassing.

Create a Report

In addition to creating visuals and speaking, you can create a report to support your presentation. Your report can further develop the ideas, issues and questions you covered in your presentation, address questions raised by the audience following your presentation, provide more value to those who attended your presentation, and create a favourable impression of you because of your desire to serve the interests of your audience beyond delivering your presentation.

Your report should not be copies of your slides, which you designed to support and enhance your presentation, and not separate documents. You might include some of the information in your slides in your report if it helps to illustrate a point, provide an example, or serve another purpose. But slides are one thing, a report is another.

You can hand out your report after your presentation or send it to those who attended. If your report is heavy on quantitative information, you might consider distributing it beforehand.

Developing a Content Outline: An Example

Here’s a simple example of how you might develop a content outline using the techniques discussed previously. In the list of possible introductions in the ‘Introduction’ section earlier in this chapter, the fourth option was ‘make an attention-getting statement.’ The example given was ‘Over the next five years, one out of every five people in our company will retire. That means 5,000 people will leave our workforce. How are we going to recruit enough people to replace our growing number of retirees?’ Let’s use this scenario to develop a content outline, assuming your audience is a small group of your company’s managers.

There are many ways to approach the presentation of content. You could begin by restating the ‘How are we going to recruit’ question. That question will frame this section of your presentation. Alternatively, you could begin with the solution to the question: ‘Here is how we are going to recruit...’

Then put the question in context by providing some numbers:

Number of people currently employed by the company

Number who will leave because of

retirement

other reasons, such as taking another job

Number who will need to be hired over next five years to

replace retirees

replace those who leave for other reasons

fill new positions created by the company’s growth

Another way to approach the content is by looking at the issue from another perspective—the skills and experience of people who will be leaving because of retirement or other reasons. How many financial managers or accountants will leave over the next five years because of retirement or other reasons? How many line managers? How many machinists? This approach allows you to discuss not only the number of people but also the skills that will be needed. So, the question is not simply hiring a certain number of people but also hiring people with the right skill sets.

To put these departures in human terms, you could (with proper permission) include brief profiles of a few of the people who will be leaving: a controller who has been with the company for 25 years, an IT director with 10 years with the organisation, or others.

Now that you have sufficiently outlined and contextualised the problem, it is time to discuss your arguments for addressing the problem.

The first step in getting content might need to be information gathering. Do a study, perhaps with the assistance of a consultant, of general recruiting practices and those of the company’s competitors. Find out what the best practices in recruiting are and which companies have stood out for their success in recruiting. Your study also might include asking employees who recently joined the company their reasons for joining and asking those who are leaving for other jobs the reasons they’re leaving. Survey employees for their opinions about working for the company, what the company could do to create a more attractive work environment, and how it might recruit people.

A second step might be the development of a strategic plan for recruiting new employees. Use ideas and best practices in recruiting that were gleaned from the study to suggest creating and staffing a position for a company recruiter, taking steps to make the company a more attractive place to work, and creating a marketing campaign to attract new workers. Your plan might also include an initiative to reach out to certain workers to ask them to stay with the company for a period of time past their retirement date. The plan can include a budget for recruiting and hiring workers.

The third step might be outlining the implementation of the plan. This would include the specific phases of implementation, who will be responsible for implementation, their responsibilities and duties, a system for measuring progress toward implementation, and so on.

Some in your audience might be sceptical that your plan will work. To win them over, the last portion of your presentation can address their main concerns. You can anticipate their concerns by speaking with some audience members you know will be sceptics before your presentation or other people in your company. By doing your research in the development of your plan, you can show how other companies have implemented similar plans that were successful in recruiting more workers.

The Close

Based on the audience memory curve (figure 7-2), remember that your audience is most likely to remember the beginning and the end of your presentation, so give some thought to creating a memorable close. Rephrase and reiterate your key message. Summarise your arguments. Call your audience to action.

Let’s go back to our example of recruiting enough people to replace retirees. In your close, you could hypothesise about what would happen if the company wasn’t able to recruit enough people to replace its retirees and others. The company’s growth could be less than expected and its profits reduced. It could have less money to reinvest in the business, hire and train workers, and maintain wage and compensation programmes that are competitive in its industry. Work could be slowed or disrupted by a shortage of key workers, and the stress on current managers and workers could increase. The company could lose workers to competitors who pay better and offer better working conditions, exacerbating the company’s worker shortage.

Call your audience to action by having them complete a survey about working conditions at the company—what they like and what they don’t like. Ask your audience to spread the word about the survey throughout the company. Ask what questions your audience has about the retirement issue and for suggestions on how to recruit people. Through this process, you can engage your audience, inform them about the issue and challenge them to help address it.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Be clear about your purpose in making a presentation.

Know your audience: who they are, their interests, their concerns and why they should care about your presentation.

Decide on a key message. Reinforce that message throughout your presentation.

Create an outline of your presentation using pens and markers, paper and index cards, and sticky notes. These tools will spark your creativity and help you develop ideas and organise your presentation.

Craft a strong introduction. Otherwise, you risk losing your audience.

Craft a strong conclusion, with a call to action.

Use the power of storytelling to engage, motivate and inspire your audience.

Endnotes

1 Laura DeMars, ‘Uh, Is This Microphone On?’ CFO.com, Mar. 2007 www.cfo.com/article.cfm/8759623/c_8766497

2 Carmine Gallo, The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs: How to be Insanely Great in Front of Any Audience, (New York: McGraw Hill, 2010).

3 Justin Locke, ‘Presentation Skills 101: How to move away from trauma and perfect your skills,’ CPA Insider, Feb. 2011 www.cpa2biz.com/Content/media/PRODUCER_CONTENT/Newsletters/Articles_2011/CPA/Feb/PresentationSkills101.jsp

4 Nancy Duarte, slide:ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations, (Sebastopol, California: O’Reilly Media Inc., 2008).

5 Nancy Duarte, ‘Create a Presentation Your Audience Will Care About,’ HBR Blog Network [website], Oct. 2012 http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2012/10/create_presentations_an_audien.html

6 Philip R. Theibert, How to Give a Damn Good Speech, (New York: Galahad Books, 1997), p. 91.

7 Carmine Gallo, The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs: How to be Insanely Great in Front of Any Audience, (New York: McGraw Hill, 2010).

8 Paul Smith, ‘The Leader as Storyteller: 10 Reasons It Makes a Better Business Connection,’ TLNT.com, Sept. 2012 www.tlnt.com/2012/09/12/the-leader-as-storyteller-10-reasons-it-makes-a-better-business-connection/

9 Bronwyn Fryer, ‘Storytelling that moves people,’ Harvard Business Review, Jun. 2003 http://hbr.org/2003/06/storytelling-that-moves-people/ar/1

10 Nick Morgan, ‘How Do You Take an Ordinary Presentation and Turn It Into a Powerful Story?’ Public Words blog [website], May 2012 http://publicwords.typepad.com/articles/2012/05/how-do-you-take-an-ordinary-presentation-and-turn-it-into-a-powerful-story.html

11 Stephen Few, ‘Statistical Narrative: Telling Compelling Stories with Numbers,’ Perceptual Edge [website] Visual Business Intelligence Newsletter, Jul./Aug. 2009 www.perceptualedge.com/articles/visual_business_intelligence/statistical_narrative.pdf

12 Carmine Gallo, ‘Thomas Jefferson, Steve Jobs, and the Rule of Three,’ Forbes, Jul. 2012 www.forbes.com/sites/carminegallo/2012/07/02/thomas-jefferson-steve-jobs-and-the-rule-of-3/

13 Jerry Weissman, ‘Learning Presentation Skills by Learning to Swim,’ Harvard Business Review, Aug. 2011 http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/08/learning_presenting_skills_by.html