CHAPTER 6

Building the Project Plan

This chapter covers the following topics:

• Creating the project management plan

• Building the project schedule

• Designing a project network diagram

• Planning for project costs

• Writing the staffing management plan

• Assuring and controlling project quality

• Communicating with project stakeholders

• Analyzing project risks

• Implementing the procurement management plan

Remember the story of Noah and the ark? When did he build that ship? Aha! He built it before the rain started. That’s the same idea with all of this planning you’re doing for each of your projects. By effectively planning, analyzing, and examining your plan from different perspectives, you increase your chances of completing your project on time and on budget.

At this point of your project, you’ve already done a great deal of work. Look back at all you’ve accomplished: you’ve created a vision, researched the technology, partnered with management, created a budget, made a WBS, and assembled your team. Phew! That’s a ton of progress, and the actual implementation of the project work hasn’t started yet. Don’t get discouraged—these activities that you’ve been doing are the building blocks of a strong foundation for the success of your project. Without all of those activities, your project would be doomed.

This chapter focuses on bringing your plan together. If you’ve done all of the preliminary work described in the earlier chapters, your plan is already coming together—which is grand. However, there are still a few more things that require your attention before you set your plan into motion. Particularly, you need to give some thought to the project schedule, the risk, and the procurement activities defined in your plan and determine if everything is reasonable. This is crucial for any project. What looks good on paper doesn’t always work well in execution.

Building the Project Plans

Depending on the size of your project, your project plans will vary. The project plan is not one big plan, but rather a collection of subsidiary plans that detail how different conditions, scenarios, and actions will be managed. It is a formal document that is reviewed and, hopefully, approved by management. The project plan is not a novel that tells the story of how the project will move along, but rather a guide that allows for changes to the project plan as more details become available.

In a predictive project, rather than adaptive projects, the project plan may evolve, but there are some elements within the project that generally do not change—or are protected from change. Of course, the foundation of the project is the project scope. Recall that the project scope is all of the required work—and only the required work—to complete the project objectives. The project scope statement defines what the project will and won’t accomplish. Once the project scope statement has been agreed upon, your change control system protects it.

Other elements of the project plan that should be immune from change are the project charter and the performance baselines. The project charter authorizes the project. It is a formal document that allows the project manager to manage the project work, resources, and schedule to deliver on the project scope. Performance baselines are time, cost, and scope objectives that the project manager must meet within the project delivery. These baselines rarely change unless an approved change happens in the project, and then these baselines are updated to reflect the approved change. In other words, you’re supposed to have enough time and budget to meet the requirements of the project scope.

Addressing Project Factors

As you begin to plan out the project in both predictive and agile approaches, you need to address the project factors that will affect how the project operates. These factors are the environmental, social, and governance conditions and can have great influence over the project approach. You may need to work with your project sponsor or product owner to address these concerns. You don’t want to ignore these factors; if you don’t have a clear plan of attack and strategy on how these factors should be managed, they’ll haunt your project throughout.

Environmental factors describe where the project work will take place. Consider how a project can affect the water, soil, air quality, and community and consider the ethical and regulatory requirements. For example, there are regulations on disposing computer equipment. You don’t want a project to disrupt or spoil the environment for ethical reasons, but also consider the goodwill of the organization, and legal requirements you’ll need to adhere to. Environmental conditions can also mean the organizational environment—such as how your project may disrupt the business, the day-to-day operations of the people working in the organization, and their attitude to the project and the change it ultimately brings to the organization. This is where politics can creep into a project, something that is inevitable in almost all projects, so you’ll need a strategy to manage perceptions of your project and how it helps, or hinders, the people in the organization.

Social factors are directly related to the politics of the organization as well. It’s no secret that there will be forces for and against your project. There will be power plays, pet requirements, and attitudes you’ll have to contend with as your project marches towards its vision. Social factors also include how society, your organization’s customers, and community view your project and what it aims to accomplish. Some projects target social good, such as setting up free Wi-Fi access in a park or an improvement in wastewater management, for example. It’s always important to ask how the project is viewed by the positive and negative stakeholders and how you can improve upon their perception of the project.

Governance is about following the rules of the organization and regulations specific to your organization’s industry. All organizations have their own way of conducting business, of getting things done. Consider how you request IT resources, how you hire contractors, or how your team schedules vacation time. There are rules or best practices within your organization to do these and other tasks that will be entirely different from how other organizations accomplish these same common activities. You want to know the rules, the governance, and work within those boundaries. Your project may also need to follow government regulations that are specific to your industry or the type of project work you’re doing. These regulations are requirements, and you must stay in compliance or there will likely be fines, penalties, and even a pause in your project execution.

Planning for Security and Privacy

Project planning, especially in IT projects, also entails addressing the security and privacy requirements of the project. The project manager, product owner or project sponsor, key stakeholders, and the project team must consider the need for privacy and security of the data they’ll be working with in the project. IT projects often encompass data that should remain private and secure, so you’ll need a policy and strategy for all team members for accessing and working with such data in the project. Many organizations require operational security, such as background screening and security clearance requirements.

Your IT project plan will likely need to address the following privacy and security considerations:

• Data confidentiality and security

• Remote access

• Authentication protocols

• Regulatory requirements

• Physical security of equipment and technology

• Intellectual property and trade secrets

Security and safeguarding data and information is always an early consideration in project planning. You’ll need to know your organization’s security policies and restrictions in order to plan effectively. You may have to work not only with your IT department but also human resources and maybe even lawyers or a legal department to understand the security requirements and approaches you’re allowed to take to remain in compliance. Throughout the project you’ll need to examine the security approaches to ensure that the team remains in compliance.

Creating Project Plan Documents

When you and your project team create the elements of the project plan for a predictive project, you can start from scratch and build your plan, or you can rely on historical information to lend a hand. Many times project managers will find that their projects are similar to past projects they’ve completed. Rather than reinventing the project management wheel, they’ll rely on past project plans to serve as templates for their current projects. There’s nothing wrong with this approach at all—it’s just working smart, not hard. Of course, when you use older plans as templates, you’ll update the older plans to reflect your current project.

Regardless of which approach you take to building your project plan, there are some common project management documents you should include in your comprehensive plan:

• Project charter This document comes from someone in a supervisory position that is higher in the organizational chart than the immediate management of the project team. This document authorizes the project. All projects need a project charter.

• Scope baseline The project scope baseline is actually a combination of three documents: the project scope statement, the work breakdown structure (WBS), and the WBS dictionary. The scope baseline is used throughout the project when there are questions about the project requirements, execution concerns, risk management, cost estimating, issues, and other project management activities. You’ll use the scope baseline as a guideline for all future project decisions.

• Time and cost estimates for each work package Recall that time and cost estimates reflect the labor and materials needed to deliver the project. This portion of the project plan will also detail how the estimate was derived, the degree of confidence in the estimate, and any assumptions associated with the estimates.

• Performance measurement baselines These baselines are boundaries or targets the project manager and the project team are expected to perform within. For example, the cost baseline may predict the amount of budget that should be spent by a given milestone, with an allowable variance. Time and cost are the most common baselines that you’ll measure your project performance against.

• Milestones and target dates for the milestones Within your project, there should be easily identified milestones that signal you are moving toward project completion. Associated with these major milestones are some target dates that you and management agree on. This allows you and management to plan on resource use, consider adjunct processes within your business, and keep all stakeholders informed of where the project should be heading—and when.

• Resource requirements Resources are people, materials, tools, equipment, facilities, and services that you’ll need to get your project done. There may be portions of your project plan that require procured resources or temporary specialized resources to complete. The required personnel, materials, and services should be identified, their availability determined, and their associated costs documented.

• Issue log Issues are risks that have occurred in the project. This doesn’t mean that the risk was identified; an issue can happen because a risk was overlooked during planning. For example, if a team member quits the project, that’s an issue; it was always a risk that people on the team could leave during the project execution. There will often be open issues and pending decisions as the plan is first created. This section of the plan identifies and documents the issues to be determined and allows the project to continue. Of course, the decisions and issues in this section of the project plan should be addressed accordingly, which may cause other areas of the project plan to be updated. In an adaptive project, issues are known as impediments or blockers and the project manager, coach, or scrum master is responsible for resolving those issues.

• Assumptions log An assumption is anything that you believe to be true but haven’t yet proved to be true. In IT, you often have to make assumptions in your planning: the software and hardware will work together, the new hardware drivers will work with the existing operating system, the learning curve of the software isn’t too drastic, and more. When you complete risk management planning, you’ll test these assumptions to prove your theories true or false. Assumptions that prove false can become risks in the project.

• Quality requirements Quality is an esoteric concept—what’s fast, good, and super to you may not be fast, good, or super to me. To have quality in an IT project, you must define the quality metrics, provide quantitative measurements that will equate to quality, and explain to the project stakeholders what the measurements mean and how they’ll map to the requirements for quality acceptance within the project. Your organization may also subscribe to quality programs, such as Six Sigma or ISO programs. You’ll need to include the project requirements for quality in these management-driven programs.

• Calendars Your project management plan needs two calendars: a resource calendar and a project calendar. The resource calendar defines when the project resources are needed, when the resources are available, and when the resources will be used in your project. Remember that resources are more than people—materials, facilities, and services are resources, too. The project calendar defines when the project work will take place. You’ll define the working hours of the project, company holidays, and busy seasons when the project work may, or may not, take place.

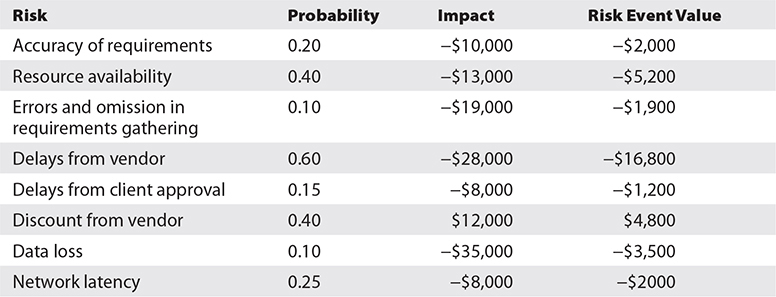

• Risk register The risk register, sometimes called the risk log, is a document that defines each risk, its probability, impact, and overall risk score, and an issue owner. The risk register should also reference or document the defined risk response for each risk event. Some projects may also include a risk owner that owns the risk and is empowered to enact the planned risk response should a risk event come into fruition. All risks are updated, tracked, and documented if their status or outcome changes.

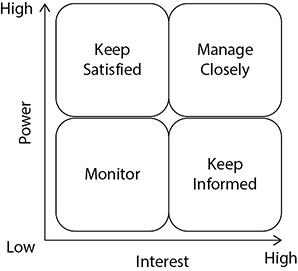

• Stakeholder management strategy Your project will likely have negative, neutral, and positive stakeholders. The stakeholder management strategy defines how you’ll bolster support for your project, fend off the negative stakeholders, alleviate fears and concerns, and promote the support for your project. You’ll use the stakeholder management strategy along with the project’s communications management plan.

• Supporting details The supporting details are any relevant documentation that influenced your project decisions, any technical documentation, and any relevant standards the project will operate under.

These project documents will be unique for each project, and you might need to adjust some of the documents as the project moves forward. Changes to the project scope, for example, will cause changes to the cost and schedule baselines, but not to the project charter. You’ll use these documents to help you refine your project plans, but also to help you in the project execution. The documents, plans, reports, and other communications that come out of project planning and project management are called artifacts. Project artifacts should be archived as part of the project. Typically, a project team member is responsible for these artifacts and their organization, location, and access.

Creating the Project Scope Management Plan

The project scope management plan defines how the project scope in a predictive project will be defined by the project management team in terms of the project requirements, how the scope will be monitored and controlled throughout the project, and how the scope will be verified by the project customers. The project scope is all of the required work for the project to be considered complete, and it’s based on the requirements of the project stakeholders. This project plan focuses on the requirements and benefits of the project—things that are in scope. It also defines, in the project scope statement, the things that are considered out of scope.

This plan directs your creation of the project scope statement, the WBS, the WBS dictionary or the product backlog in an agile environment. Recall that these three elements comprise the project scope baseline. Once you’ve created the project scope statement and your stakeholders have approved the scope, you’ll decompose the scope into the work packages. Each work package, as I’m sure you remember, can be estimated for time and cost within your project. Along with the WBS, you’ll create a companion document—the WBS dictionary. This document defines what the work packages are, what resources are needed for the work packages, and the time and cost estimates for each work package.

The project scope management plan also defines how the scope might be allowed to change. If you’ve ever managed a project before, you know that stakeholders change their minds—often. The scope’s change control system is defined in the project scope management plan—you don’t want (or need) change requests fluttering into your inbox on a daily basis. In theory, if you’ve accurately collected the project requirements, there should be few to no change requests. In practice, however, stakeholders aren’t as thorough as you are in collecting and offering requirements. Generally, change requests are needed for the project scope for four reasons:

• Errors and omissions Oops! The stakeholders or the project manager goofed and didn’t accurately include all of the requirements in the project scope. When there are errors or omissions in the project scope, the scope must be revised to reflect the newly added requirements.

• Value-added changes Sometimes there is a great reason to add elements to the project scope. The additions can be profitable for the organization, make the deliverable better, or create benefits that are low in cost and high in value. Value-added changes are documented and folded into the project scope.

• External events There’s a world outside of your project that doesn’t care about your project. New releases from vendors, new laws and regulations, and competitors can all change your project scope. External events are a common element that can change the direction of your project scope.

• Risk events A risk is an uncertain event or condition that can have a positive or negative effect on your project. Some of your project work may be too risky, so it might be carved out of the project scope. Other events, such as a discount from a vendor if you add a few elements, is a good deal, so you might add the new elements to the project scope.

When a change request is introduced, the change must pass through the project’s integrated change control system, which is part of the project’s project management information system. Change requests must be documented and explained as to why the change is warranted. Undocumented change requests are not implemented in the project—get the change request in writing, define who started the change request, and explain why the change might be needed. Once the scope change request has been documented, it enters the scope change control system. Technically, as you can see in Figure 6-1, there are four change control systems: scope, schedule, costs, and contract.

Figure 6-1 An approved change request has an effect on the entire project.

In an adaptive project the product owner acts as the change control board. The product owner evaluates each change for its business value to the product and determines if it should be added to the product backlog. If the change is added to the product backlog, it is also prioritized in the backlog—it doesn’t automatically go to the bottom or top of the list.

A scope change request passes through the configuration management system, which examines the scope change request’s effect on the features and functions of the project’s product. For example, a scope change request could be to add reporting features to a piece of software. The reporting features would affect the features and functions of the project’s product, so the change would be evaluated, weighed for value, and then documented as part of the product scope, if approved.

All change requests, scope or otherwise, pass through integrated change control to assess the effect of the change on the entire project. A scope change request could affect the project costs, schedule, quality, human resources, communications, risk, and even procurement. Integrated change control is the requirement that a proposed change request be examined for its true impact on the project. Once the change request is determined to be accepted or rejected, the result is communicated to the appropriate stakeholders and documented in the change log. Yes, even changes that aren’t approved go into the change log as a record of what happened to the change and why it was rejected.

A change to the project scope can affect the product scope statement, the project scope, the WBS, and the WBS dictionary; it can even have ripples into the project plan. All of these documents and affected plans need to be updated to reflect the approved change. When a change enters the project scope and it’s approved, then you’ll also need the time and monies to reflect the approved change. Approved changes to the project’s scope and budget will cause the corresponding baselines to be updated, too.

Changes that happen early in the project usually don’t cost as much as changes that are requested later in the project. It’s easier to change the project plan and its documents than to change the physical work that has already been completed in the project. The physical work of the project and the results of project execution are also affected by this scope management plan. The work results must be examined by the project stakeholders to verify that the results are acceptable to them. This examination is called scope verification, and the project’s scope management plan defines when and how the verification will happen.

Scope verification usually happens at the end of project phases and always at the end of the project. The goal of scope verification is for the project customer to accept the deliverables that the project team has created. Scope verification is an inspection-driven process that the customers, key stakeholders, or project champions do with the project team and project manager. If there are mistakes or errors in the inspection, the project manager can create a “punch list” of things that must be corrected before the project deliverables are accepted by the project customer.

Defining the Project Schedule Management Plan

Your predictive project must have a definite set of deliverables that mark its end. Projects also require a finish date. Some projects’ finish dates are a touch firmer than others—for example, building a football stadium before the season begins. Or consider a project that management says must be completed before a peak business period. Other projects, such as the release of a new e-mail program within an organization, can tend to go on forever and evolve into runaway projects.

Runaway projects stem from a loosely guarded project scope, poor planning, and lack of research. Of course, the longer a project takes to produce its deliverables, the more the project will cost. In addition, to make it personal, a missed deadline can impact bonuses, incentives, and raises for project managers and team members. The best way to reach a target date for completion is to plan, plan, plan. And then analyze the plan. And then adjust and readjust the plan until it is acceptable and the team is ready to implement the technology. The project schedule management plan defines several things for the project manager and the project team:

• What project activities need to be completed

• An estimate of how long the project activities will take to complete

• When the project activities will need to happen and in what order

• What resources are needed for the project activities and when the resources will be needed

• How the project schedule can be adjusted, compressed, analyzed, or manipulated for the best possible outcome for the project

• How the schedule will be monitored and controlled

• A cadence to the project communications, regularly scheduled events, and communications

A project schedule should be a reflection of the WBS, the accumulation of all of the work packages within the project, and the assignment of resources for each task. Most new project managers work around specific target dates for milestones, phases, and a completed project. This makes the most sense, right? IT professionals are used to working off a specific calendar for so much of their lives that this next concept can be a little confusing at first: if possible, do not schedule project tasks to happen on a specific date.

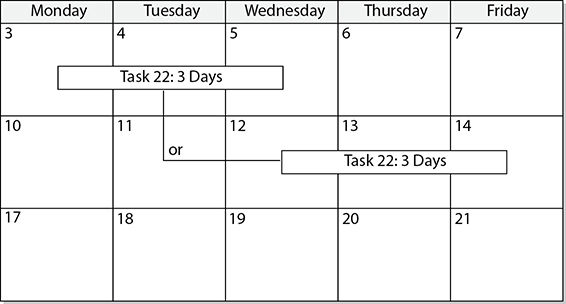

Project managers should not work around specific dates when creating the project plan, but instead should initially work around units of time—for example, one day, two weeks, three months, and so on. Rather than saying a specific work unit will take place next Thursday and Friday, it’s better to say that a specific task will take two days to complete. Why? Isn’t next Thursday and Friday the same as two days? Yes, and no. Assigning two days to complete a task rather than two specific days allows you to move the task around within your project plan. Figure 6-2 demonstrates the concept of working in units of time rather than specific dates. This little trick allows for a process you’ll learn more about later in this chapter: project compression.

Figure 6-2 Assign tasks to be completed in units of time rather than by specific dates.

Working with units of time rather than specific dates for each of the tasks within your project plan allows you to tally your plan to a specific amount of time—regardless of when the actual project is implemented. For example, if tasks within your project are all assigned a deadline based on the project start date of July 9 and end date of November 2, each task is very time constrained and date specific. However, this same project takes 90 workdays (depending on the year and allowing for weekends). When you assign tasks units of time within the span of 90 workdays, regardless of when the actual start date commences, the project can shift 90 days into the future from the start date.

Often, however, project schedules and deadlines are determined before the project even begins. We’ve all been there, right? We’re handed a project to create an application that must be delivered by an unrealistic date. There hasn’t been real reflection on the needed time to create a quality application by the given date. In these instances, the project manager still needs to address the project, the work decomposition, and the assignment of resources to complete the work, just as with a project where the end date is not known.

During project planning, you’ll create the WBS based on the project scope. Once you’ve created the WBS, you can enter the activity list into Microsoft Project or your favorite project management information system (PMIS) software. Once you enter the activities into Microsoft Project, you can create a Gantt chart like the example shown in Figure 6-3. It shows a mapping of each of the units of work required to complete each phase of the project.

Figure 6-3 A Gantt chart maps activities to a project calendar.

The Gantt chart is ideal for simple, short-term projects. It is a timeline of the events with consideration given to tasks that can be completed concurrently within a project’s life span. Traditional Gantt charts have some drawbacks:

• Gantt charts do not display detailed information on each work unit. (Microsoft Project does allow project managers to add task information and notes within a Gantt chart on each task.)

• Gantt charts display only the order of tasks.

• Gantt charts do not clearly reflect the order of tasks in multiple phases.

• Gantt charts do not reflect the shortest path to completion.

• Gantt charts do not reflect the best usage of resources.

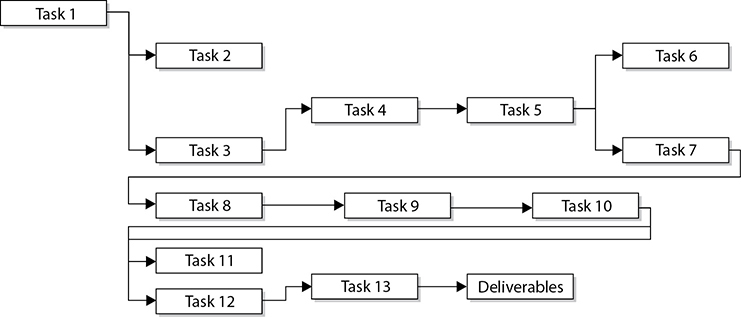

To address these issues, project managers can use a project network diagram (PND). PNDs are fluid mappings of the work to be completed. (Figure 6-4 shows a sample of a portion of a network diagram.) Incidentally, the terms “PND,” “project network diagram,” and “network diagram” all refer to the same workflow structure—don’t let the different names confuse you. Such diagrams enable the project manager and the project team to tinker with the relationships between tasks and create alternative solutions to increase productivity, profitability, and the control of a project.

Figure 6-4 Network diagrams demonstrate the relationships between tasks.

A PND visualizes the flow of work from conception to completion. Network diagrams provide detailed information on work units and enable project managers to analyze tasks, resources, and the allotted time for each task. You can use a PND to determine the flow of work to predict the earliest completion date. Network diagrams are ideal for these situations:

• Detailed project planning In large projects that may span several months, or even years, a network diagram is essential, as it can correlate each task in relation to the project scope. Through a network diagram, the project manager, management, and the project team can see the entire project plan from a high-level view and then zoom in on a specific portion of the project plan.

• Implementation tracking As tasks are completed on time, or over time, the number of time units used can accurately display the impact on dependent tasks within the project. If you use software to track the project implementation, the reflection of the impact is automated for you. Imagine a task that has four dependencies and is two weeks late in completion. The failure of the task to be completed on time now pushes the dependent tasks back by two weeks. A network diagram can illustrate this impact and allow the project manager to react to the changes by adjusting resources or other dependent tasks.

• Contingency plans Network diagrams enable a project manager to play out “what if?” scenarios with any work unit within the project plan. A project manager can adjust units of time to see the impact of the work units on the entire project. For example, it may be obvious to see an impact on dependent tasks when a work unit is two weeks late, but what about units that are completed early? Imagine that pay incentives are based on project completion dates—a series of work units that each have one day shaved off of their target completion times may have positive impacts on all future tasks.

• Resource control A network diagram shows the flow of work and the impact of the finished tasks on the rest of the project. By using the Gantt chart’s assigned resources to a unit of work, a project manager can add or remove resources to a task to complete it faster or delay the completion. Resources can be both workers and physical objects such as routers, faster computers, and leased equipment.

Using the Precedence Diagramming Method

The most common method of creating a network diagram is the precedence diagramming method (PDM). PDM requires the project manager to evaluate each project activity and determine the order in which the activities should be completed. You’ll determine which activities are successors and which are predecessors. In other words, each activity in your project has some activities that must come before it in a particular order and activities that will come after the current activity, also in a particular order. Once this information is obtained, you can begin to snap the pieces of the PDM puzzle together. You must give careful consideration to the placement of each activity, as all activities are connected even if they are scheduled to run concurrently.

Each unit of work in a network diagram using PDM is represented by a rectangle called an activity node. Predecessors are linked to successors by lines and the flow of the work is always left to right, as Figure 6-5 demonstrates. One work unit can be both a successor and a predecessor. For example, the task to install and configure a web server may first require the installation of an operating system; only after the web server task is completed can the web pages the web server will host be added.

Figure 6-5 Network diagrams flow from left to right and connect predecessor and successor tasks.

To begin creating the network diagram using PDM, a project manager and project team have to determine the order of tasks to be completed. Basically, a project manager asks, “What tasks must be completed before the next tasks can begin?” The activity list, which you derived from your WBS work packages, is what you are sequencing. You do not want to include activities that are too short in length to be useful. Based on your project, you may have work units that last days or weeks—generally not hours.

As you add tasks to the network diagram, draw a line between tasks to connect them in the successor/predecessor relationship. As expected, the network diagram is read left to right, top to bottom. Most tasks within the diagram will have a successor and predecessor—except for the first and last tasks in the project. Once the diagram has been completed with successor and predecessor tasks, it is considered a connected network. A project manager, or anyone involved in the project, can trace any activity through the network.

The relationship between activities is what allows a project to move forward or to wait for other tasks to complete. An accurate description between tasks is required for the project manager to analyze and adjust each task in the network diagram. Figure 6-6 shows the dependency types you may have between tasks.

Figure 6-6 Dependencies describe the relationship between tasks.

There are four types of dependencies:

• Finish-to-start (FS) This relationship is the most common. It simply requires the predecessor task to complete before the successor task can begin. An example is installing the network cards before connecting PCs to the Internet.

• Start-to-start (SS) These tasks are usually closely related in nature and should be started, but not necessarily completed, at the same time. An example is planning for the physical implementation of a network and determining each network’s IP addressing configurations. All tasks are closely related and can be done in tandem.

• Finish-to-finish (FF) These tasks require that the predecessor task and the successor task be completed at nearly the same time. In this relationship the successor tasks cannot be completed before the predecessor task is completed. An example is rolling out a new software package and finishing the user training sessions. While users are in the new training session, the new software should be installed and configured on their workstations by the time the training session ends.

• Start-to-finish (SF) These rare tasks require that the predecessor not begin until the successor finishes. You won’t find yourself using this activity all that often. It’s often used with just-in-time scheduling for inventory and manufacturing instances. For example, if you’re opening a coffee shop, you’ll want your inventory of coffee to be on hand as close as possible to when the construction of your shop is done. The coffee has to be ordered to officially open the shop, and the construction has to be done before you can open the doors. You’ll need to time the order of coffee with the completion of the construction in order to open your doors on time without your merchandise spoiling—or tying up your cash flow in inventory that’s not being sold.

Managing Logical Constraints

A constraint is a boundary or limit based on the project. You’ve dealt with constraints before: a preset budget for your project, an inflexible deadline, limited availability of computer hardware, or locating a resource with a specific skill. Constraints are any factors that can limit your options. The project manager and team must document constraints and their risks examined, and then the project manager must plan on how to meet the project objectives within the identified constraints.

When it comes to scheduling activities, you can also create constraints on the relationships you assign between your activities. For example, an FS relationship is constrained by the completion of the predecessor before the successor can begin. This is a natural constraint. This relationship between activities is sometimes called hard logic. Hard logic (aka mandatory logic) describes the matter-of-fact order of activities. For example, you must install the operating system before you install the application. On the other hand, soft logic is when the project manager decides to do tasks in a particular order based on experience, conditions in the project, time, or other reasons. This logic is also called discretionary logic. For example, it is a good “old school” practice to have completed all the coding before beginning the testing phase. It is not mandatory—you can unit-test certain modules that are complete before all the coding is done—but it is preferred to have all the coding complete before any testing begins.

In some conditions, you might want to schedule a task to wait before starting, and that’s called lag time. Lag time means that you’re adding time to the activity’s start date. The opposite of this is called lead time, when you’re moving the activity’s start date backward to allow it to overlap with other activities. Lag time is always positive time or waiting time. Lead time is always negative time and often overlaps with other activities.

Often in project management, projects have preset deadlines that require project managers to work backward from the assigned completion date. The problem is that the person establishing the deadline may not realize the work required to complete a project by that given date. Unfortunately, this is often the way project management works: you’re assigned a deadline and then you have to figure out how to complete the tasks by that date.

Whenever possible, avoid using specific dates for tasks unless it is absolutely required. With date constraints, you are signifying that a certain task must happen on a specific date, regardless of the completion of tasks before or after it. The best method of assigning tasks is to use a unit of time and then predict when the task may happen based on the best- and worst-case scenarios for the predecessor tasks’ completion.

There are three types of date constraints:

• No earlier than This constraint specifies that a task may happen any time after a specific date, but not earlier than the given date.

• No later than This constraint is deadline oriented. The task must be completed by this date—or else.

• On this date This constraint is the most time oriented. There is no margin for adjustment, as the task must be completed on this date, no sooner or later.

You can set these constraints on a task by using your project management software.

Management constraints are dependency relationships imposed because of a decision by management—this includes the project manager. For example, suppose a project manager is overseeing the development of a web-based learning management system. The website will allow students to register for classes, check grades, and pay for their tuition, all online. The e-commerce portion of the project and the database development portion of the project are scheduled to happen concurrently. Because of the unique relationship between the two tasks, the project manager decides to rearrange the work schedule so that the database portion of the project must finish first and then the e-commerce portion of the project may begin. The project manager accomplishes this by changing the relationship between the tasks from start-to-start to finish-to-start. Now the database task must be completed before the development of the e-commerce portion. This is another example of soft logic.

There are actually eight types of constraints that you may use in your project schedule management plan:

• As soon as possible (ASAP) When you specify a task constraint of ASAP, you schedule the associated task to occur as soon as it can. This is the default for all new tasks when assigning tasks from the start date. This constraint is flexible.

• As late as possible (ALAP) When you have a task with this flexible constraint, you schedule the task to occur as late as possible without delaying dependent tasks. This is the default for all new tasks when scheduling tasks from the end date.

• Start no earlier than (SNET) A task assigned the SNET constraint starts on or after a specific date. This constraint is semiflexible.

• Start no later than (SNLT) This semiflexible constraint requires that a task begin by a specific date at the latest.

• Finish no earlier than (FNET) This constraint requires that a task be completed on or after a specified date. This constraint is semiflexible.

• Finish no later than (FNLT) This semiflexible constraint requires that a task be completed on or before this date.

• Must start on (MSO) A task with this constraint must begin on a specific date. This constraint is inflexible.

• Must finish on (MFO) This inflexible constraint indicates a deadline-oriented task. The task must be completed by a specific date.

Managing Technical Constraints

Technical constraints stem from FS relationships. Most often within an IT project, tasks will be logically sequential to get from the start to the end. These constraints are the simplest and most likely ones you’ll find in a project. The technical constraints you may encounter when building your network diagram fall into two major categories:

• Discretionary constraints These constraints allow the project manager to change the relationship between activities based on educated guesses. Imagine two tasks that are scheduled to run concurrently. Task A, the design on the web interface, must finish, however, before Task B, the development of the web application, is well under development. Because of the cost associated with the programmer, the project manager changes the relationship between the tasks from SS to FS. Now the first task must finish before the second task begins.

• Resource constraints A project manager may elect to schedule two tasks as FS rather than SS because of a limitation of a particular resource. For example, if you are managing a project that requires a C++ programmer for each task and you have only one programmer, then you will not be able to use SS relationships. The sequential tasks that require the programmer’s talents dictate that the relationship between tasks be FS.

Managing Organizational Constraints

Within your organization, multiple projects may be loosely related. The completion of another project may be a key milestone for your own project to continue. Should another project within your organization be lagging, it can impact your own project’s success. For example, suppose that you work for a manufacturing company that is upgrading its software to track the warehouse inventory. Your project is to develop a web application that allows clients to query for specific parts your company manufactures. The success of your project requires the warehouse inventory project to be completed before your project can end. You enter these relationships into your network diagram as FF, with the origin activity representing the foreign project.

Scheduling with Gates

We all know that gates are things that swing open and allow you to pass through. In project management, there are also gates that are part of the project governance. A governance gate governs how the project is allowed to move from one phase of the project into the next phase of the project. A governance gate defines the conditions that must exist for the project to move forward—for example, forms completed, budget reconciled, and stakeholder approval of the work completed so far.

Another common gate is tied to quality: you can’t move on—that is, you can’t pass through the quality gate—until certain conditions are met. A quality gate requires an inspection of the work your team has completed to confirm that it meets the quality requirements of your organization, PMO, customer, or even laws and regulations. If the quality is sufficient, then the quality gate will swing open and your project can move forward.

Consider, for example, a project that includes a phase to replace old network cabling with new cable in the plenum (the area above the drop ceilings). There are regulations, industry practices, and standards that all affect this project. The quality gates would require an inspection of the installed cable for accuracy, standard adherence, and compliance. If the cables pass the inspection, the project can continue onto its next gate; if not, the project is stalled until the problem is fixed. Once the problem is corrected, the gate swings open and the project can move forward.

Another gate, for projects in the public domain, is legislative approval. A government-sponsored project has different accountability than a project using private funds. Legislative approval would review the work and either cancel the project or continue to invest in the project based on its merit and success.

Building the Project Network Diagram

Because the project network diagram can be a long and detailed map of the project, you probably don’t want to enter it into a computer on the first draft. One of the best methods of building and implementing the PND is on a whiteboard using sticky notes. A project manager, along with the project team, should begin by defining the origin work unit on a sticky note and then defining the project deliverables on another sticky note. On the left of the whiteboard, place the origin task, and on the right, place the deliverables. Now the project manager and the project team can use the activity list to identify the relationships between the units of work.

You and the team will continue to create the PND by adding activities in the order they should happen given upstream and downstream activities. This can be a long process, but it’s necessary in order to complete the PND. Chances are, you’ll be moving activities around and changing their relationships—that’s why the whiteboard and sticky notes are so nice.

Once you have roughed out the network diagram, you’ll refer to your time estimates for each activity. You can use the WBS, PERT, and supporting details to reiterate the amount of time allotted for each task. Once you’ve recorded the units of time, you may then begin to assign the resources to the tasks. Use sticky notes to move and strategize the relationships between the tasks, connecting each task with an arrow and identifying the relationship between the tasks to be implemented. You will have to consider the availability of the resources to determine if tasks can truly run concurrently within a network diagram. In other words, you can’t assign a programmer to two activities that are supposed to happen at the same time.

After you have constructed the initial diagram, examine the activity lists and the WBS to determine if any tasks or project deliverables have been omitted. If you find omissions, update the WBS and task list to reflect the work and deliverables you’ve found. Examine the relationships directly between tasks but also the relationships of tasks upstream and downstream. Review these relationships to see if you can edit any of the tasks to save time or resources. If so, rearrange the necessary tasks to update the diagram. A balance of acceptable risk and predictable outcome is required to discern the type of relationships involving each task.

A project manager must also consider business cycles, holidays, and reasonable times for completing each task. For example, a company has sent new cellular modem cards to all of its employees working out of the office on laptops. Part of the deployment is a request that the users in the field connect to the corporate LAN as soon as they receive their cellular cards. There must be a reasonable amount of time allotted between the cards being shipped to the users in the field and the confirmation that the cards have been received.

Finally, once you’ve created the network diagram, break for a day or two to allow the team to ponder any additional tasks or other considerations in the workflow prior to implementing the plan. When you reconvene to finalize the network diagram, consider the amount of risk you’ve allowed into the project by asking these questions:

• Are there adequate resources to complete the project?

• Are the time estimations accurate?

• Are there too many concurrent tasks?

• Are resources spread too thin?

• Is this a proven plan?

• Is the plan realistic?

There are two other project network diagrams that you should be topically familiar with. The first is the critical chain method (CCM). CCM is similar to the critical path method (CPM), but it accounts for the availability of project resources, whereas CPM assumes the project resources are available all the time for the project work.

Another diagramming technique is GERT, the Graphical Evaluation and Review Technique. This diagramming approach has questions, branches, and loopbacks that allow you to move forward, backward, or sideways in the project according to the outcomes of the project work. For example, GERT may ask, “Are the results of network testing greater than 90 percent or less than 90 percent? If greater than 90 percent, go on to Activity D; if the results are less than 90 percent, return to Activity C.”

Analyzing the Project Network Diagram

One of the most satisfying accomplishments in IT project management is to step back and, looking at the PND, follow the project conception through each task to the final deliverable of the project. Don’t get too infatuated—this network diagram will likely change.

Now that the PND has been constructed, you can find the critical path. The critical path is the sequence of events that determines the project completion date. The critical path is the path with the longest duration from project start to project completion. For example, imagine that you have created and analyzed your network diagram. Most likely it depicts multiple paths from project start to completion. Usually, just one of the project paths will take longer than any of the other paths. This is the critical path. (I say “usually” it’s just one because you could have two or more paths that tie for the longest paths in the project network diagram.) It’s called the critical path because if any activities on it are delayed, the project completion date is also going to be late.

Calculating Project Float

Given you know that activities on the critical path cannot be delayed, what about activities that are not on the critical path? Can these activities be delayed? Yes, usually they can—but there is a limit to the amount of time an activity not on the critical path can be delayed. This limit is called float. (Sometimes this is called “slack,” but it’s the same business.) There are three different flavors of float:

• Free float The length of time a single activity can be delayed without delaying the early start of any successor activities

• Total float The length of time an activity can be delayed without delaying project completion

• Project float The length of time the project can be delayed without passing the customer’s expected completion date

Most project managers allow their project management software to calculate the available float on each activity, but it’s really not that hard to do manually. To find the float for each activity, first find the earliest possible start date and the earliest possible finish date for each activity by completing what’s called the “forward pass.” Once you’ve got this info, you do just the reverse through the “backward pass”—find the latest possible start and latest possible finish date for each activity. There are a few different methods for calculating project float. Here’s one of the most common approaches.

Calculating float is one of the toughest topics in this book for most people to grasp. It’s weird, it’s confusing, and most project managers never do this stuff manually—they’ll let Microsoft Project do it for them. I’ll walk you through a scenario, but the process of calculating float is also a great example of how watching someone do this may be easier than reading about it. And for that reason, I’ve also created a video that demonstrates this entire process.

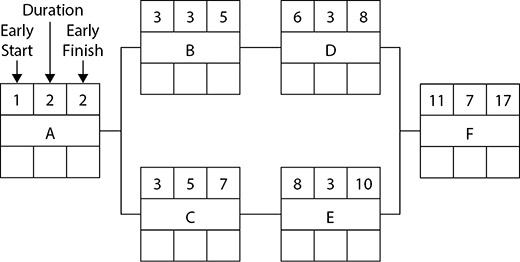

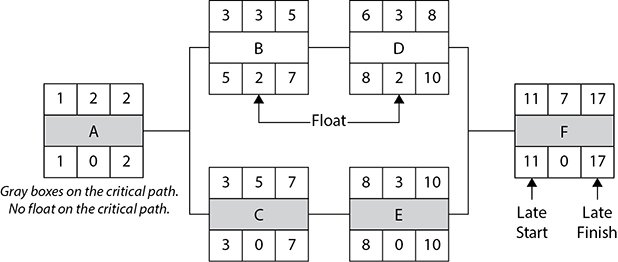

For this example, we’ll be using the simple project network diagram shown in Figure 6-7. (You can print Figure 6-7 from the online resources that accompany this book if you’d like; it’s in Adobe Acrobat PDF format. See Appendix C for accessing the online resources.) As you can see, there are two simple paths to completion: ABDF and ACEF. The number over each node represents the duration of the activity. If you add up the duration of each path, you’ll find the critical path—the longest path to completion. In this example, it’s ACEF because it takes 17 days, while ABDF takes only 15 days.

Figure 6-7 The longest path to completion is the critical path.

Now let’s try the forward pass. (Again, there are different methods of finding float, so don’t be concerned if you’ve been exposed to a different one.) Follow these steps:

1. Make the Early Start (ES) for Activity A one, because you’ll start on Day one. Add the duration of the activity to the ES and you’ll have three. Now this part trips up some folks: subtract one day from the value of the ES and the task duration to arrive at the Early Finish (EF) of the activity. The reason is that the duration of Activity A is only two days, not three, right? In other words, if you start on Day one, you should have two days of work to get to Day two. The EF for Activity A is two.

2. The next activities are Activity B and Activity C. The ES for both of these will be three. Why? Because Day three is the next day in the schedule, the earliest possible day to begin either activity.

3. Let’s finish the ES for activities B, D, and F first. The EF for Activity B is the ES, plus the duration, minus one, for an ES of five. The ES for Activity D is six and the EF for Activity D is eight. The ES for Activity F is 9, and the EF for Activity F is 15.

4. Now let’s do activities C, E, and F. The ES for Activity C is three, and the EF is seven. The ES for Activity E is eight, and the EF is ten. Activity F is the last activity in the project, so you can bet it will be on the critical path—with no float. The ES for Activity F is actually 11, because Activity F cannot begin until your project team completes Activity E. So, the EF for Activity F is actually 17. Figure 6-8 shows the project updated with all of the ES and EF dates.

Figure 6-8 The ES and EF dates are found by completing the forward pass.

Now that the forward pass has been completed, it’s time to do the backward pass. It’s a cinch; just follow these steps:

1. Begin with the last activity in the network diagram, Activity F, which has an EF of 17. Make the Late Finish (LF) the same as the EF value: 17. The reason is that Day 17 is the latest day the project can finish without being late.

2. The Late Start (LS) for Activity F is the LF value, minus the duration of the activity, plus one. Yes, plus one. Because you’re going backward in the network, you’ll add one rather than subtract one. This accounts for the full day of work you have completed on the first activity and the last activity. So, Activity F has an LF value of 17, less the duration of 7, plus 1, which equals an LS of 11. It’s no coincidence that the EF and the LF have the same value of 17. It’s also no coincidence that the ES and LS have the same value of 11. This is because this activity is on the critical path.

3. Next let’s do activities D, B, and A. The LF for Activity D is ten—one day prior to the ES of Activity F’s LS. You get the LS for Activity D by subtracting the duration of the activity, plus one, which equals eight. The LF for Activity B is seven and the LS is five. The LS for Activity A is, well, it’s the first activity in the project. Do you think it will have any float? Hey! You’re right—it’s on the critical path, so we can skip it for now.

4. Let’s go back and complete the backward pass for E, C, and A. The LF for Activity E is ten, and the LS for Activity E is eight. The LF for Activity C is seven, while its LS is three. The LF for Activity A is two, and its LS is one. Figure 6-9 shows the completed backward pass.

Figure 6-9 The backward pass reveals the LF and the LS.

To finalize the process of finding float, you’ll subtract the LF from the EF and the ES from the LS on each activity. Wherever there’s a zero, you have a task on the critical path; wherever there’s a number, the activity has float. In this example, activities B and D have two days of float. Okay, technically they both don’t have two days of float; there are two days of float on the whole project. Or you could say that Activity B and Activity D can each have one day of float, or either activity can have two days of float. However you slice it, if either activity goes two days beyond its expected completion time, this project is late.

Forecasting Adaptive Project Completion

Adaptive projects don’t move through the same schedule approach that predictive projects do. Recall that adaptive projects work in iterations of two- to four-week time periods. The team selects the most important items from the top of the product backlog based on how much work they think they can complete in the iteration. The requirements from the product backlog are called user stories and are assigned story points. A user story is just a way of writing a requirement so everyone can understand it. User stories follow this formula:

As a role

I want this feature

So I get this value

For example, “As a salesperson, I want to place orders through my phone app, so my customers can get their product delivered quickly.” Based on how difficult the user story is to create, it’s assigned a point value that is relative to the user stories. For example, an easy user story might have three points, but a difficult user story might have 13 points. The point value isn’t hours of work, it’s just relative sizing, like T-shirts get sized small, medium, large, and x-large.

Over time and with experience, the team will learn how many points they can actually complete in an iteration. For example, they may predict they can complete 36 stories points worth of work in four weeks. The number of points the team can complete may vary wildly at the beginning of the project as the team’s efficiency settles, but when the number of story points accomplished settles, it’s called the team’s velocity. Velocity is how many points the team can reliably complete in an iteration. In this example, the velocity is 36 user story points. To predict how long the project will last, you’ll examine how many user story points are in the product backlog and divide that number by the team’s velocity.

For example, the product backlog has 128 user story points remaining and the team’s velocity is 36. 128 divided by 36 is 3.55, which indicates four more iterations are needed to complete all of the user stories in the product backlog. If each iteration lasted four weeks, you could safely predict the project will take 16 weeks to complete based on the current velocity.

Creating the Project Cost Management Plan

The project cost management plan defines how the project will be estimated and budgeted and how the costs will be controlled. In Chapter 5, I detailed the costs of project management. This is a great example of how projects and project management planning are integrated—what you do in one area affects another. You need to plan specifically for project costs, but you need other project management plans in order to plan effectively for project costs. As more and more information becomes available in your project, you can plan in more and more detail.

The first portion of the project cost management plan should define how you’ll complete project cost estimating. In your organization, you may have some specific rules about cost estimating, metrics you’re required to use, and even a chart of accounts that defines standardized costs for certain types of project work. These organizational requirements that control how and what you plan are called enterprise environmental factors. Always follow the rules and policies of your organization when it comes to planning and estimating for costs.

As a reminder, to create accurate cost estimates, you’ll need six things:

• Project scope baseline

• Project schedule

• Human resource plan

• Risk register

• Enterprise environmental factors

• Organizational process assets

You’ve seen all of these inputs to cost estimating before—except for the risk register and the human resource plan. Each of these inputs has some cost factor associated with it, which is why you’ll need all of them to predict how much the project is going to cost the organization. I’ll address the human resource plan and the risk register later in this chapter.

Cost budgeting, the second process that the cost management plan defines, is the aggregation of the costs of each work package in your project’s WBS. It is the sum of all the costs the project will incur and is put into an authorized budget so that the project can execute the fully composed project management plan. The project’s cost budget does not include any reserves for time or risks—these are special budgets for your project, not part of the project execution. The performance of your project is measured, often enough, against the approved project budget.

Your project’s cost budget is largely built on the cost estimates of your project. That’s why it’s so important for you to document the basis of your cost estimates—how did you determine it would cost your project $24,987 for a particular server configuration? My point is that the project cost estimates are only as good as the supporting detail. If the supporting detail is fiction, then you can bet dollars to donuts the project’s budget is going to be skewed as well.

One of the most important parts of the project cost management plan is how the project costs will be controlled and monitored. The project manager has the responsibility of tracking project costs for all areas of the project scope that have a cost factor. There must be cost reconciliation between what the project manager says the project will cost and what the project actually costs in execution. Monitoring and controlling of the project costs uses several approaches:

• Leading the team to do the work properly the first time to avoid cost overruns

• Thoroughly investigating the true costs of change requests

• Tracking costs to project deliverables against the total costs of the project by phase and overall project costs

• Measuring project performance against the costs of the project to reach said performance

• Stopping unapproved changes of all sorts from entering the project

• Making corrective actions to bring cost overruns back into alignment with the project cost baseline as much as possible

Basically, you’ve got to work with the project team and stakeholders to prevent waste by accurately planning the project work and then accurately doing the project work. When there are mistakes in the project, go to the problem immediately to try to find a solution for the problem. As a project manager, you’re responsible for wastes, cost overruns, and deficits. The actions you take should always be linked to project performance.

Planning for Project Quality

Ask ten people what they think quality is, and you’ll probably get ten different answers. Quality, when it comes to project management, is the entire project and how the project satisfies the stated and implied requirements of the project scope. Quality is creating for the project customer exactly what was promised in a way that’s cost and time effective. Quality is more than just balancing the scope, time, and cost of a project, however—it’s a fitness for use and a conformance to project requirements. In project management, you achieve quality by planning quality into the project—not inspecting the results of the sloppy work and then fixing problems later. It’s always more cost effective to do the work properly the first time.

The quality management plan defines what quality is for your project, how you’ll plan for quality, and then how you’ll inspect the project work to ensure that quality exists within the project deliverables. The first step in planning for quality is to understand what the project customers want—this means you’ll refer back to the scope baseline. By understanding what is expected of the project in exact terms, you can plan to achieve the expectations in exact deliverables. This is one of the reasons it’s so important to get the customer stakeholder to approve the project scope statement and the WBS. You don’t want to be planning to achieve quality for the wrong requirements.

When you begin to plan for project quality, you’ll start with the requirements of the project, and then you’ll need to address quality assurance. Quality assurance (QA) is an organization-wide quality policy or program that your organization subscribes to. Quality assurance examines the quality requirements of the project, inspects the results of quality control, and ensures that the project is using the correct quality standards and terminology in the project. Your organization may use a home-grown quality policy that staff has written, or it may participate in a program such as Six Sigma or Total Quality Management. These quality programs usually have the same theme that W. Edwards Deming, the grandfather of quality, created in his Quality Circle: Plan, Do, Check, Act. My point is, your organization may already have a standardized approach to quality assurance that your project will need to follow. That’s great!

Your quality management plan also defines the quality control technique you’ll use in your project. Quality control is the inspection of the work results that your project creates. By inspecting the work results, you’ll know if the work has been done to plan, if the work adheres to the QA metrics, and whether the work needs to be corrected before the project moves forward or it’s acceptable to you. Consider a project to install a network in a new office building. In this construction project, you might have 1,500 network connections to create throughout the building. For each network drop, you’d have a specific requirement of where the jack is to be positioned, how the network cable is punched down, and how the cables are secured between the network drop and the patch panel. The specifications of the work are the requirements, the planning of how you’ll achieve the requirements is the quality assurance, and the inspection of the network is the quality control.

Along with your quality management plan, you may also create or adapt a process improvement plan. The process improvement plan is a project management plan that defines how the processes within the project can be analyzed for potential improvement. The process improvement plan is ideal for projects where there’s a repeatable process, such as installing 1,500 network cables, or for project types that your organization may do over and over as part of your business. It’s really a good idea to use a process improvement plan because it helps you, the project manager, really think about and understand the workflow of a project and how you might shave off some wasted time by getting rid of non–value-added activities.

You can use the process improvement plan to define and analyze several things about your project:

• Process boundaries You’ll identify where a process begins and where a process stops. By understanding the process boundaries, you can document what conditions are needed for a particular process to begin and what conditions must be true for a process to stop.

• Process configuration identification This fancy-schmancy term just means that you identify all of the components within the process. You’ll document how a process is completed, what the process interfaces are, and what each process in your workflow accomplishes.

• Process metrics If you don’t measure, you can’t improve, but in order to measure, you need to know what the metrics are for measurement. You can measure a process on speed, cost, efficiency, throughput, or whatever metric is most appropriate for the type of work the process is participating in.

• Targets for improvement Once you’ve completed process analysis, then you can begin to re-engineer the processes, set goals for process improvement, and try small changes to the process to measure what results the changes may bring.

I’ll talk more about the execution of quality and the inspection of project deliverables in Chapter 11. It’s perfectly acceptable for a project manager to use a previous project’s quality management plan to help achieve quality in the current project. The application of quality control, however, will likely change for each project, as each project has different variables than the last.

Preparing for Managing a Project Team

I think you and I would agree that every organization in the world is unique when it comes to managing employees, the culture of the organization, and how much authority the project manager has over managing their project team. The enterprise environmental factors, the structure of the organization, the policies and guidelines of the organization, and the experience of the project manager all affect how much authority and decision-making ability the project manager has over the project team. As a project manager, you need to understand how you’ll manage the team and still be within your “rights” as a project manager in your organization. You don’t want to overstep your boundaries, but you’ll need to manage your team effectively so that you can get them to complete their assignments as required.

Considering the conditions within your organization, you’ll create two plans to address how you’ll lead and manage your project team: the human resource plan and the staffing management plan. And, yes, as with other project management plans, you can adapt your current plan by drawing on plans from previous, similar projects. The first plan to discuss is the human resource plan. This plan defines the needed roles and responsibilities of the project team. A role is a definition of a type of team member who does a specific kind of actions—for example, network engineer, application developer, database administrator. Roles are generic descriptions of the project team members, not employees named specifically. Attached to the roles are the responsibilities or actions the roles are to fulfill on the project team.

One approach that’s worked for me is that when I plan for the project work, I don’t worry about who will be doing what. I focus on the role that will take care of the specific work. For example, you might assign the entire network cabling activities to the network engineer; later, once the initial planning is done, you’ll determine how many specific people can fill the role of the network engineer and slice the activities across the people who can satisfy the one specific role in the project. This way, during planning the project team, you’re not worried about getting a specific person, you’re just identifying the skills the roles will need in order to accomplish the specific responsibilities.

The human resource plan also addresses the type of structure the project is operating in. Recall our conversation on functional, matrix, and projectized structures from Chapter 3? The type of structure you’re in will help you as the project manager to determine who has to report to whom. In a functional structure, where the functional manager is in charge, the reporting structure is easy and shallow. Similarly, in a projectized structure, the team works on just one project at a time, and the project manager is in charge. In a matrix structure, however, your project team members have to report to you, their functional managers, and any other project managers that they work for. Communications, reporting, and resource management get messy in a matrix structure, so ample planning is needed.

The second plan, the staffing management plan, addresses how project team members will be brought on to and released from a project team. It’s this plan that is so important in a matrix structure, as you’ll need to coordinate timetables with other project managers and the project team members. This plan addresses the project calendar—when the project work is expected to take place. It also addresses the needed resource calendars—when the project resources are available for project work.

The staffing management plan also includes an assessment of what is needed for team development. This can include training, team activities, and expectations of team leadership roles for senior project team members. You can’t expect the project team to complete the project without the appropriate skills to complete the project work. Training is an essential part of the team development, and it’s also considered a cost of quality.

The staffing management plan can, and I believe should, include a definition of how a rewards and recognition system works. If your project can reward the project team for a job well done, then the project team should know the rules, the rewards, and how they can achieve those rewards. Rewards can be financial, time off, contributions to their employee review, or other incentives for each employee. What motivates one employee may not motivate someone else. As a general rule, you should shy away from “zero-sum rewards,” which are rewards only one person can win, such as a reward for being employee of the month. As a side note, you will want to reward the project team with genuine praise when it’s appropriate. This isn’t something that’s in your project plan, but when a project team member does a great job, you should acknowledge it. I’ll talk more about team development in Chapter 7.

Writing the Project Communications Management Plan

Without a doubt, the best method to communicate with others is face-to-face communication. However, in most organizations, that’s not always a possibility. So, as a project manager, you’ll need to create a communications management plan to address other approaches for communicating and define what is and is not allowed, preferred, and required.

In order to create solid management alliances, you’ll need to communicate. In order to communicate effectively, you’ll need a communications management plan. Considering stakeholder analysis, the project manager and the project team can determine what communications are needed. There’s no advantage to supplying stakeholders with information that is not needed or desired. Time spent creating and delivering unneeded information is a waste of resources.

The communications management plan helps to determine which person needs what information, when that person needs the information, the modality in which the information is expected, and which stakeholder will supply the information. The communications management plan identifies the appropriate communication technologies, types of forms, and types of meetings, and it creates a schedule of when communication is expected to occur.

A communications management plan organizes and documents the process, types, and expectations of communications. It provides the following:

• A system to gather, organize, store, and disseminate appropriate information to the appropriate people. The system includes procedures for correcting and updating incorrect information that may have been distributed.

• Specifics on how confidentially constraints of sensitive information within the project or organization will be addressed and documented, and the role of the individual(s) who may manage the confidential information. Project managers often have access to sensitive information, such as financial, human resources, and even classified government information. The plan must establish safeguards within the organization (or project) to ensure that confidential information is protected.

• Details on how needed information flows through the project to the correct individuals. The communication structure documents where the information will originate, to whom the information will be sent, and in what modality the information is acceptable.

• Information on how the information to be distributed should be organized, the level of expected detail for the types of communication, and the terminology expected within the communications.

• Schedules of when the various types of communication should occur. Some communications, such as status meetings, should happen on a regular schedule; other communications may be prompted by conditions within the project.

• Methods to retrieve information as needed.

• Instructions on how the communications management plan can be updated as the project progresses.

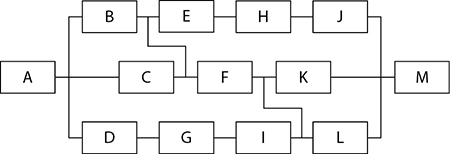

It’s been said that 90 percent of a project manager’s time is spent communicating. You’ll be communicating with the project team, the project sponsor, business analysts, customers, vendors, and other stakeholders all the time. People will want information from you, and you’ll want information from other people. One tool that you can add to the communications management plan is a communications matrix, shown in Figure 6-10. This matrix lists all of the stakeholders and maps out who needs to speak to whom. You can get fancy and create a legend beyond what I’ve done here, but basically it’s a tool that can help you facilitate communication between certain stakeholders and the project.

Figure 6-10 A communications matrix identifies which stakeholders must communicate.