1 Radical Adaptability

Black Rock Desert in northern Nevada is probably the worst place on earth for thousands of people to gather during the last week of August. Midday temperatures on the lifeless salt flats hover near 110°F. The nearest electrical connections and running water taps are almost ten miles away. You need goggles and a face mask for protection from the sudden dust storms with their fifty-mile-per-hour winds. And yet, since 1991, Black Rock Desert has drawn as many as eighty thousand people annually to the Burning Man celebration.

By design, Burning Man is a strange and otherworldly place, where many of the outside world’s rules don’t apply. For nine days out of the year, a community springs up in Black Rock Desert as a social experiment in which money is forbidden and extreme creativity is celebrated. It’s the only place you’ll ever see Deadheads and classical musicians composing new harmonies together, while anarchic pyromaniacs join with tech elites to build gigantic flaming artworks, new age spiritualists exchange deep thoughts with business executives, and tree huggers work side-by-side with gun lovers to maintain the campgrounds and protect the fragile desert ecosystem.

It all works, not in spite of the harsh desert environment but because of it. The shared communal predicament of enduring such adverse conditions sustains a deep sense of commitment to a shared mission and belonging amid scorching heat, frigid nights, and whirling dust storms. “Communities are not produced by sentiment or mere goodwill,” Burning Man cofounder Larry Harvey once said. “They grow out of a shared struggle.”1 The struggle for existence is what drives collaboration at Burning Man. The unforgiving desert is a crucible for creativity.

Keith Ferrazzi had been going to Burning Man every year for sixteen years when the pandemic shut down plans for the 2020 gathering. At the time, he reflected with coauthor Kian Gohar, who is also a “burner,” on the parallels between the world’s shared struggles and the lessons offered by the world of Burning Man. The founders of Burning Man refer to it as an “experiment in temporary community dedicated to radical self-expression and radical self-reliance.”2 After many months of research, some of our team members who had been to “the Burn” realized that this depiction also precisely describes the pandemic. Burning Man is a small and deliberate social experiment, and the pandemic turned out to be its own kind of social experiment for the workplace, an accidental and tragic experiment, conducted on a global scale.

Without doubt, the pandemic foisted on the globe tragic levels of adversity and an unwelcome social experiment in grief and privation. And yet, because of the hardships it placed on our lives and how it required us to react, the pandemic also turned out to be a source of tremendous insight, creativity, innovation, and community for many of us, similar to the shared experience of thriving in the desert. We hope it will be a powerful and positive inflection point for us all, and we aspire to share the most important leadership lessons learned through this book.

Adaptation happens to be the one thing that human beings do better than any other animal on the planet. We’re not the biggest, we’re not the fastest, and we don’t have the sharpest teeth or the strongest claws, yet we are the dominant species on earth, thanks to our extreme and relentless adaptability to change.

Work Isn’t Working

For decades, Keith and Kian have preached that industry disruption has been so painful precisely because leaders have failed to adapt their strategies and ways of working to the unique demands of rapidly accelerating disruption. The two of us have designed and facilitated hundreds of leadership team engagements globally, coaching executives to harness innovation and exponential technologies to build a better future. In our experience, it’s always a challenge to persuade these executives that their team cultures are stuck in the past and desperately inadequate for the future ahead. The competencies required for team leadership have been shifting for decades, and it’s time to recognize the advantages of meeting these trends. How we work hasn’t been working for a long time, but we’ve continued to cling to outdated ways of work as though we were hanging by our fingernails over an abyss.

Then, in 2020, the entire world was struck with a level of disruption that few had ever imagined. The need for a new level of adaptability in the workplace became a dire necessity, not just a competency of the truly best. All the practices Keith and Kian had been recommending to executive teams for years suddenly became must-do items rather than nice-to-haves. In a single year, adversity ushered in more changes in ways of doing business than we had seen in decades. It was a weird new world of work, a great laboratory in so many ways, one that offered all of us a blank slate on which we could reinvent how we work, how we experiment at work, and who we invite into our conversations.

From our perspective, a window of opportunity had flown wide open, and we were excited to hear many people acknowledge how the crisis had brought out the best in them and their teams. “We know how to do this,” said Cathy Clegg, leader of transformation initiatives at GM manufacturing. “This is where GM truly shines.” She and others, when forced to improvise, rose to the challenge with unprecedented levels of tenacity, innovation, and some of the so-called soft skills of leadership: humility and vulnerability. We had been granted permission to explore without borders, the way we had felt free to ride bicycles at midnight across the roadless flat desert floor at Burning Man.

When leaders were compelled to set aside red tape and delegate more decision-making, results flowed faster than ever before. Companies responded by collaborating more intensively and communicating more thoroughly. Team members were more candid with each other and spoke more freely and directly because the emergency eliminated opportunities for conflict avoidance and passive-aggressive communication. Team members also became more generous. They broke out of siloed that’s-not-my-job behaviors. And out of sincere concern for each other, they asked, “How can I help?” The crisis set teams free to take action. And it made teams better.

All around the world, big companies and small businesses alike were forced to discover new processes, new markets, and new business models that proved to be lasting sources of competitive advantage. London’s top Michelin-star restaurants got into the business of home deliveries and cook-it-yourself meal kits.3 Stagekings, an Australian theater set-building company, pivoted to making home office desks under the brand name IsoKing—and looked to expand to Europe.4 Spice seller Diaspora Co., with its suppliers in India locked down, switched to taking preorders as a cash-flow strategy and saw sales surge 35 percent.5 In Taiwan, where airlines devoid of passengers in early 2020 put a new emphasis on shipping packages, China Airlines enjoyed a surprisingly profitable second quarter.6 Even in a radically disrupted business environment, companies learned they could thrive if they could crack the code of radical adaptability and master its lessons.

At the same time, though, working in a crisis left many feeling stressed and worn down. The hours were long, and all the improvised jury-rigged systems and processes suffered from frequent breakdowns. Without proper support for sustaining these new modes of work, many companies were merely “crisis adapting.” Without the right tools and coaching, some felt overwhelmed and defeated. Many people had a hard time seeing the magic and the possibility. They wanted it all to stop. They just wanted to go back to work.

That notion gripped Keith with a sense of urgency bordering on panic. What if this new world of work ended up permanently tarred by its association with the pandemic? What if tradition and inertia proved to be so strong that all the bad old habits snapped back into effect as soon as the pandemic ended? Crises are so exhausting that it’s natural to want to return to the comfort of the familiar. But if we were to do that and resume working the way we had before, such a return would be yet another disaster, one that would last long after the pandemic had passed into history.

At Ferrazzi Greenlight, where our job is to accelerate team transformation, we’d noticed that some teams we were coaching had adapted extremely well in certain areas, while other teams had proven innovative in very different ones. Keith began organically piecing together a methodology for clients composed of insights and best practices gleaned from the others. He began hosting small virtual gatherings of clients to exchange ideas. That’s when he realized what was needed was a central forum for exploring and sharing what the best of the best were doing to survive.

It became clear to us at Ferrazzi Greenlight that we should never go back to the way things were. We couldn’t afford to lose such hard-won momentum. So we pledged to turn the experiences and lessons learned during the crisis into big wins for our customers, for our companies, and for each other. We would preserve all the practices we had honed during the crisis. And while we’re at it, we pledged to make our work in this new world more purposeful, more meaningful, and more humane.

Let’s never just go back to work.

Let’s go forward!

Research Basis for This Book

At Ferrazzi Greenlight’s research institute, we launched what we thought at the time would be a several-month project called Go Forward to Work (GFTW). We recruited change agents from big companies, entrepreneurs, and some of the most well regarded thought leaders—people who shared our vision of how the rules of work were being rewritten day-by-day and didn’t want the opportunity squandered. We wanted to create a place to stop and cocreate what the future would look like five years forward: a place to analyze how much change would be necessary and what exciting possibilities lay ahead, all in light of the best practices we were seeing and collectively sharing from our pandemic experiences.

To that end, we developed partnerships with Harvard Business Review Press, Dell Technologies, Salesforce, SAP, EY, Anaplan, LHH, WW, Headspace, World 50, and many other brands and associations. Our teams of researchers supported the production of dozens of stories appearing in Forbes, Fast Company, the Wall Street Journal, and Harvard Business Review. We reached thousands of leaders through team engagements, coaching sessions, and virtual town halls in partnership with our GFTW faculty fellows (practitioners and thought leaders who guided and published our research) and GFTW fellows (internal change agents from across industries and corporations). We leveraged online conferences and podcasts with direct calls to action to join this movement and contribute to our collective research at GoForwardToWork.com.

We knew we had a responsibility to not let this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity pass us by. And so we documented all the innovations and best practices that were happening on the fly and considered how they could lead our vision in the years to come. And we crowdsourced a research-based methodology for what leadership means in a radically volatile world.

A New World of Work Is Emerging

Before the pandemic, Keith and Kian had been to hundreds of events exploring the future of work, a term that in our view was just a loosey-goosey feel-good phrase for intellectual pontification by thought leaders and executives who thought the future of work was on some distant horizon. But both of us struggled with this term, because the so-called future of work had been unfolding in real time all around us for years before the pandemic. And although we were screaming from the rooftops about the need for executive teams to change, many companies just punted and operated in a manner reminiscent of yesteryear. But suddenly in 2020, this future of work became the present of work, and every leader realized they had to pay attention. They had to pivot or get left behind.

Our research at GFTW discovered commonalities among those who were thriving and revealed the difficulties that most leaders were struggling with. We found that the urgency of the situation melted the frozen routines and the ossified protocols that had long posed obstacles to growth and change. We came to see a new world of work emerging from the old world (see figure 1-1). In the new pandemic world, companies attempted things that they would never have tried to do under normal circumstances in the old world. Projects nobody wanted to take on suddenly made sense. Digital transformation projects that previously had a five-year implementation plan materialized literally overnight. Product development cycle times were reduced to fractions of their prior times. Small, accidental experiments bore fruit that led to greater successes. Companies rethought their workplace physical footprint and shuttered their office buildings. Like never before, they became open to flexible work arrangements and pivoted week by week, cocreating major strategic choices on the fly. The levels of mutual support were astounding as team members co-elevated—they lifted each other up in an esprit de corps of resourcefulness and experimentation.

FIGURE 1-1

The old and new worlds of work compared

“Covid became the common enemy,” recounted Pam Klyn, vice president of product and brands at Whirlpool. When the pandemic forced the closure of the R&D labs at Whirlpool, workers resorted to testing washing machine parts in their home garages and basements. They exchanged parts to be tested by meeting fellow team members at arranged spots on specific stretches of interstate highways. Once Whirlpool’s new technical center is ready to open in southwest Michigan, Klyn’s teams have told her they want to take their work forward, not backward. “It’s about sustaining energy,” Klyn explained. “People want to hang on to the gains.”

Radical Adaptability: A Blueprint for Success in the New World of Work

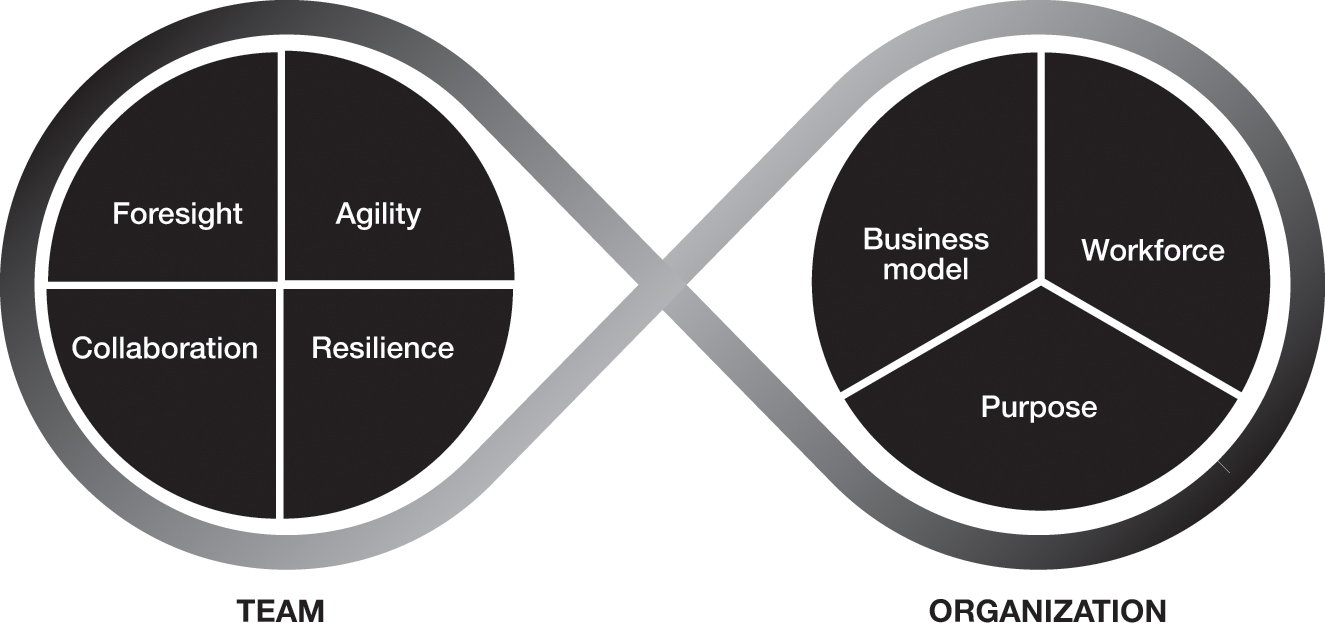

From our research interviewing more than two thousand leaders through the pandemic, we identified a consistent pattern of successful leadership competencies across industries and synthesized that into a new leadership methodology for a future of accelerating change and uncertainty. We call this methodology radical adaptability (figure 1-2). It presents all the lessons of crisis leadership in the form of a sustainable model for leading continuous change through the coming years of unexpected turmoil, opportunity, and transformation.

FIGURE 1-2

Radical adaptability

The seven chapters that follow represent best practices in how to build a radically adaptable future to compete in this new world of work. Chapters 2 through 5 describe how to build a radically adaptable team, and chapters 6 through 8 introduce how to leverage that team to build a radically adaptable organization. Together these seven chapters form an infinite loop that reinforces radical adaptability and transformation.

Chapters 2 through 5 tackle core leadership competencies that, when stacked on top of each other, create a circular flow state for teams to operate at peak performance:

- Collaborate through inclusion. Embrace the possibility of richer diversity of virtual, remote, and hybrid teamwork to drive innovation exponentially forward.

- Lead through enterprise agile. Extend and expand the cultural ethos of short-term sprints that kept us on our trajectory during the crisis, and find an operating system that allows us to thrive sustainably amid continued volatility.

- Promote team resilience. Bounce forward in the face of setbacks and recognize that good leaders strive to maintain the emotional and physical energies of the team.

- Develop active foresight. Learn to see around corners to avoid unsuspected risk and to systematically explore new possibilities.

The final three chapters present an operating model for your radically adaptable team to build a radically adaptable organization by deploying the radical adaptable team skills of collaboration, agility, resilience, and foresight to three enterprise-wide applications:

- Future-proof your business model. Develop an ongoing process of experimentation to create and realize your company’s future vision of itself.

- Build a Lego block workforce. Redesign your workforce to support a flexible, nimble, cost-effective, and creative future.

- Supercharge your purpose. Build a movement for radical adaptability by discovering and communicating your organization’s long-term purpose.

The essence of radical adaptability is that it is predictive, proactive, and progressive, very unlike the typical response to change, which is inherently reactive and conformist. By definition, adaptability is the ability to adjust to new conditions. Adaptability is a coping mechanism. Radical adaptability is a transformational mechanism. Radical adaptability prompts you to constantly anticipate change, reinterpret it, and transform yourself through change. Through radical adaptability, you embrace the new world of work and grow with it, while others merely adjust and adapt to it.

Competing in the New World of Work

We believe radical adaptability best describes what every company can and must do within the next eighteen months to leap forward five years. Otherwise, you’ll be left behind in the dust by your competitors. In 2020, we accelerated change that was years in the planning, even though the pandemic was exhausting. Going forward, we believe you can thrive and win the future, if you use the research methodology offered by radical adaptability and do it in ways that strengthen your organization and not wear it out. The urgency of change is real. The challenge is how to maintain your energy and passion through change and not crumble from its strain and pace.

It has become clear to us that sustaining competitive advantage in a post-pandemic world will require leaders to master radical adaptability every day and in every role in the organization. The specifics are different for every company, but the radical-adaptability framework will inspire leaders to catapult their organizations forward, make up for lost time, embrace new realities, and win new frontiers.

Though the word transformation suffers from severe overuse these days, radical adaptability requires true transformative leadership. Traditional work processes, business models, and workforce structures will not prepare us for the future that’s rising up faster than most would assume. For example, take a moment to visualize what you assume might be the reality of your job or industry in five years. There’s a good chance that all those things need to get done in the next eighteen months if you want to be anything more than a follower and if you don’t want to lose ground to your competitors. The hurdle for success has been raised exponentially, and the terrain has become simultaneously rockier. This new world of work requires a new set of attitudes, processes, and practices that will achieve not just 10 percent improvement over yesteryear, but 10X transformation to prepare you for a future that is faster than you think.

The difference is all in how we choose to go forward.

Embedded in our innate human gift for adaptability is our instinctive drive to create meaning out of the ashes of catastrophe. Disasters have always served humankind as engines for innovation and progress. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 also gave Chicago the most advanced fire prevention laws on earth. Cholera epidemics in the 1800s gave New York City world-class health and sanitation codes. The deadly 1995 Kobe earthquake provided Japan with the world’s strictest and smartest building regulations. In a similar way, the Covid-19 pandemic provided us with a new set of world-class codes for work, if we go forward with them.

Disasters don’t just destroy. They reveal. They uncover the weaknesses in human structures—both physical and social—that had long outlived their usefulness when disaster struck. That was true in 1871, when wood-framed buildings in Chicago’s tightly packed downtown burned like matchsticks. It was also true in 2020, when hierarchies and bureaucracies were exposed for their inadequacies while teams and networks of teams rose up and declared, “This is when we are at our best.”

The pandemic revealed in ways big and small much of what hadn’t been working with work for a long time: top-down, overplanned, draining, reactive, bureaucratic, static, and narrowly mission oriented. Now we’ve all been invited to join a new world of work that has been emerging for many years, one that’s collaborative and inclusive, agile, resilient, anticipatory, reinventive, flexible, and purpose-driven.

New ways of thinking don’t come easy. Sometimes it takes immersion in a new, strange world to recognize that the familiar world has not been serving you very well.

Leading in the New World of Work

Some years ago, Keith brought one of the world’s top automotive executives to Burning Man, someone we’ll call François, for confidentiality purposes. François showed up in a sport shirt, khaki shorts, and a state of mind that was curious but highly skeptical.

Once he got over the mild shock of what everyone else was wearing (or not wearing), François naturally gravitated toward the hundreds of gearheads who create Burning Man’s mutant vehicles—bizarre mobile machines that are a mix of engineering genius and artistic inspiration. A 2019 Motor Trend feature on Burning Man included images of a fire-breathing dragon built on the chassis of a GMC Safari van. Another featured vehicle looked like a forty-foot steel shark with the guts of a Cadillac, and yet another was a double-decker bus expanded to a quad-decker and tricked out in LEDs.7

François spent a lot of time with the mutant vehicle creators. One in particular was an eccentric genius who, François discovered, was a design engineer at one of François’ competitors, and who kept spewing fantastical musings of what was possible in the future of mobility and how hard he had to work to make this dream a reality. François assumed he knew the car industry very well, but this mad genius showed him how much he lacked in inspiration and imagination. François was shaken to his core.

One night, he brought that eccentric genius engineer back to the camp for something Keith calls the otherness exercise. Keith asks each guest to return at dinner time with a stranger they have strong judgments about—someone who, outside the world of Burning Man, they would consider strange and outrageous and would avoid. Over our meal, Keith facilitated the conversation as he would in a team-building exercise, prompting the dinner guests to get to know the stranger who they might have considered “the other,” as a way to develop empathy and understanding for the unknown. In business and in life, empathy is a certain path to expanding your insights and sense of possibility.

Before the end of Burning Man, François confided that his experience left him questioning everything about his leadership style. He pondered why he hadn’t offered his most creative people the chance to fully express themselves through their work, much as the wild genius engineer had. And he wondered if the excitement and engagement he had witnessed among the mutant vehicle makers could also be unleashed in his own team back at work. He’d begun to question whether he had unwittingly served as a tool of a hierarchy and a bureaucracy that no longer served him, his employees, or the company? By the end of the week, François had swapped out his sport shirt and khakis for a Day-Glo loincloth.

After Burning Man, François reentered his familiar world feeling newly energized and eager to pass the inspiration on to his team. He decided to create ways to listen to their ideas more carefully—both formally and informally—and to give them more freedom to make decisions at deeper levels of the company and to trust them to cocreate bolder solutions, with fewer intermittent checks and balances. The auto industry’s transformation to electric power was then just on the rise, and although an enterprise commitment to transformation was far from articulated, some members of François’s team insisted on working on what that transformation strategy could and should be. Over the next eighteen months, they developed some truly brilliant new designs and led the company to accelerated product development results that would not have happened otherwise.

The many months we spent in the strangeness of a pandemic exposed all of us to the same possibility of personal transformation that François faced at Burning Man. We could either duck into a tent and wait for the dust storm to pass or find our way to new heights by exploring the unknown through radical adaptability. During the pandemic, we witnessed how fast and how far people can go when they’re given the chance to rise to the occasion and manage their way out of one crisis after another. That is the ethos of radical adaptability.

Shaping the Future

Building a new world of work won’t be easy. The coming years of recovery and renewal offer a historic opportunity to remake our organizations and our futures, but only if we accept this as an inflection point for true reinvention. The radically adaptable way of leading described in this book is designed to future-proof both your personal leadership style and your business. That’s because it is built on the assumption that for the foreseeable future, we will all be going forward to work in a new world of constant change and disruption. That’s the promise of this book: to help you develop a sustainable leadership style and strategy to guide you through low tide, tsunamis, and fair seas. We firmly believe that the number one lesson from the pandemic must be that we have to develop a strategy to survive similar shocks in the future, be they events or the relentless disruption of technological and social change.

As this book goes to print, our GFTW research continues, and we extend to you our invitation to join the movement and contribute to the research, at GoForwardToWork.com. The coming pages represent the best practices and insights derived from more than a year of this crowdsourced research. To execute radical adaptability, however, the methodologies by themselves will not be enough to compete in a new world of work.

Why? Remember the name Tilly Smith.

In late 2004, Tilly Smith was a ten-year-old girl from Surrey, England, who was vacationing with her parents during winter break at a small, secluded oceanfront resort in Phuket, Thailand.

Tilly was strolling the beach with her mother when the water at their feet started behaving very strangely. “The sea was all frothy like on the top of a beer. It was bubbling,” she would later recall.8

In school two weeks earlier, right before the winter break, Tilly had seen a documentary about the devastating Hawaiian tsunami of 1946, which killed ninety-six people in the seaside town of Hilo.9 The video described how the tsunami had taken the people of Hilo by surprise because they had failed to recognize the danger signs when the waters in Hilo Bay began frothing and fizzing minutes before the big wave arrived.

Frightened by what she knew about the water bubbling at her feet, Tilly pulled on her mother’s arm and warned her that a tsunami was on its way. Her mother was skeptical, but Tilly started screaming about her lesson in school. Tilly’s mother finally relented, and she and Tilly’s father spread the word. Hotel security cleared the beach, and the great Indian Ocean tsunami struck minutes later. In the hours that followed, more than two hundred thousand people were killed by tsunami waves all across the Indian Ocean basin. Thailand’s coastal towns suffered tens of thousands of deaths, but the secluded beach where Tilly and her family were staying was the only beach in Thailand with zero fatalities.10

When Tilly returned home to England, she was hailed as a hero for saving more than a hundred lives that day, all because she’d learned her school lessons so well.11 But that’s not really what made her a hero.

It was important, of course, that Tilly had knowledge and insight about tsunamis and why the water was behaving so strangely. But that was only half the equation. What made Tilly a hero was her resolve, her belief in what she knew, and the courage it took to put her knowledge and insights into action.

Tilly knew something important about the world that her mother didn’t. When Tilly’s mother first tried to shrug off her daughter’s warnings, Tilly didn’t back down.

Instead, she got angry. She told her mother, “Right, I’m leaving you, because there is definitely going to be a tsunami.” That was enough to impress Tilly’s mother that her daughter might be right. Together with Tilly’s father, they alerted hotel security. Minutes later, when the tsunami struck, all the guests and staff were safely sheltered in the upper floors of the resort hotel.12

Courage, not knowledge, is what made Tilly Smith a hero. Her knowledge was essential, but without the courage of her convictions—without expressing her righteous anger to her mother in that crucial moment—her knowledge about tsunamis would have died with her that day, along with her parents and everyone else on the beach.

From all the committed change agents who contributed to this book, this is their challenge to you: to be this kind of hero. To be like Tilly. Be the lonely voice who speaks up because you can see what’s coming in the new world of work. Take this knowledge, absorb these insights, and then exercise the courage required to be the radically adaptable leader who puts them into action. And when your colleagues push back, when maybe even your boss tells you that you can’t pull this off, that it won’t work—don’t back down.

Think of Tilly Smith.

Stand by what you know to be true.

Fight for the actions you know are needed to compete as a radically adaptable leader, and win in this new world of work.

Show you have courage that’s at least the equal of the world’s most heroic ten-year-old.