An endless number of computer crime cases is available for you to read. Most of the crimes presented in the following sections come from the Department of Justice Web site, online at www.cybercrime.gov. In these cases, we’ll look at several types of computer crime and how computer forensic techniques were used to capture criminals. The cases presented here illustrate some of the techniques that you will learn as you advance through this book. As a forensic investigator, you never know what you may come across when you begin an investigation. As the cases in this section show, sometimes you find more than you could have ever imagined.

Hacker Sentenced for Identity Thefts from Payment Processor and Retail Networks

Alberto Gonzalez, 28, led a hacking and identity theft ring that compromised record-breaking numbers of credit cards. For his part in the crimes, Gonzalez received the longest sentence imposed for criminal hacking to date. In March 2010, in separate cases, U.S. District Court judges sentenced Gonzalez to two 20-year prison terms for hacking into several retail networks and a major payment processor.

Gonzalez committed access device fraud, aggravated identity theft, computer fraud, conspiracy, and wire fraud. He and his associates hacked into major U.S. retailers, including the TJX Companies, BJ’s Wholesale Club, OfficeMax, Boston Market, Barnes & Noble, and Sports Authority. He also led the group that breached the Dave and Buster’s restaurant chain electronic payment systems. The second prison sentence, 20 years and one day, was for two counts of conspiracy for assisting others in breaching the networks of card processor Heartland Payment Systems, supermarket chain, Hannaford Brothers Co. Inc., and nationwide convenience store chain, 7-Eleven.

Between July 2005 and his arrest in May 2008, Gonzalez and his group hacked into retail credit card payment systems by installing sniffer programs that captured payment card numbers used at the stores and by wardriving. Wardriving involves driving around in a car with a laptop computer looking for unsecured wireless computer networks. Gonzalez and his co-defendants stole more than 40 million credit and debit card numbers from major retailers. They sold the numbers and also committed ATM fraud by encoding the stolen data onto blank cards and then withdrawing cash from ATMs.

Gonzalez’s ring hid and laundered their fraudulent gains by moving the money through bank accounts in Eastern Europe and using anonymous Internet-based currencies in the United States and abroad.

Gonzalez gave malware to other hackers that enabled them to bypass firewalls and anti-virus programs to break into companies’ networks. (Malware is discussed in the Security Awareness section below.) Gonzalez admitted that his assistance allowed his co-conspirators to steal tens of millions of card numbers, adversely impacting hundreds of financial institutions.

In the largest investigation to date of its kind, the U.S. Secret Service worked abroad and in the United States using computer forensics to solve these cases. In July 2007, Secret Service in Turkey worked with Turkish agents to obtain Ukrainian suspect Maksym Yastremskiy’s laptop while he danced at a nearby nightclub. After downloading data, U.S. agents returned the computer to Yastremskiy’s hotel room. Instead of user names, Yastremskiy’s accomplices used secure communication networks with numerical IDs.

Detectives noted Yastremskiy’s chats with an American who sold millions of stolen credit card numbers to Yastremskiy. The American used the identity “201679996.” The detectives worked with Carnegie Mellon University experts to link the numbers to a Russian e-mail address that belonged to Gonzalez. Ironically, Gonzalez had been working with the Secret Service as a consultant since 2003.

Shortly thereafter, the Secret Service arrested an Estonian hacker and found more than 40 million unsold credit card numbers linked to the break-ins at U.S. companies on two Latvian servers.

For months, Gonzalez hid in the National Hotel where he was living off more than $400,000 cash. He had buried another $1.1 million in the back yard of his parents’ house. On May 7, 2008, agents raided Gonzalez’s hotel room, condo, and parents’ home. Gonzalez was then arrested.

Source: Wired.com, August 17, 2009, http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2009/08/tjx-hacker-charged-with-heartland; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs, http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2010/March/10-crm-329.html.

Man Charged with Operating Online Scheme to Steal Income Tax Refunds

In June 2010, Mikalai Mardakhayeu was arrested and charged for his alleged role in an online phishing scam. The international scam was designed to steal U.S. taxpayer income tax refunds. Mardakhayeu is a Belarusian national living in Massachusetts. He was charged with conspiracy and wire fraud.

As alleged in the indictment, in 2006 and 2007, Mardakhayeu and his co-conspirators operated Web sites that offered lower-income taxpayers online tax return preparation and electronic tax return filing services at no cost. The fraudulent Web sites claimed to be authorized by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Co-conspirators in Belarus allegedly collected the data entered by taxpayers and then changed the returns so that the legitimate tax refund payments would be redirected to U.S. bank accounts that Mardakhayeu controlled. In some cases, his co-conspirators increased the amount of the claimed refund.

Allegedly, his co-conspirators electronically filed the modified returns with the IRS and various state treasury departments. As a result, the U.S. Treasury and state treasury departments deposited stolen refunds of approximately $200,000 into bank accounts that Mardakhayeu controlled. If convicted, he could be sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS), http://www.justice.gov/criminal/cybercrime/mardakhayeuIndict.htm.

In this case, the forensic examiner might have found the files used to create the fraudulent Web sites. If the files were deleted, parts or all of them could have been recovered. Other evidence might include the actual data entered by the victims. The server logs and bank deposit records might have recorded who accessed the accounts. The forensic examiner has a wide variety of tools available to extract data and deleted information.

Newell Rubbermaid Network Hacked for Botnet and Adware Scams

In June 2008, a federal judge sentenced 21-year-old Robert Matthew Bentley to 41 months in prison and payment of $65,000 in restitution for conspiracy and computer fraud. Bentley and others (who are still being investigated) infected hundreds of computers in Europe with adware. The cost to detect and neutralize the adware was tens of thousands of dollars. Bentley and his co-conspirators were paid for installing the adware through a Western European-based operation called “Dollar Revenue.”

The investigation began when the U.S.-based Newell Rubbermaid Corporation and at least one other European-based company reported a computer intrusion against the companies’ European networks to the London Metropolitan Police.

This complex, multiyear, international criminal investigation also involved the U.S. Secret Service, the Finland National Bureau of Investigation, London’s Metropolitan Police Computer Crime Unit, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Each of these law enforcement organizations detected and responded to botnets of computers secretly controlled by Bentley and his co-conspirators. Evidence was found on computers in Florida that were used in the actual intrusions and to receive payment for placing the adware.

See U.S. Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS), http://www.justice.gov/criminal/cybercrime/bentleySent.pdf. See also “Hacker Pleads Guilty to Computer Fraud” at http://pcworld.about.com/od/adware/Hacker-Pleads-Guilty-to-Comput.htm.

This case spanned several countries. National and international law enforcement agencies had to work together to track the illicit computer accesses. By installing the adware and accepting payments, the suspect unwittingly left a trail of forensic evidence. The evidence may have included items such as the parts of the program used to control the botnets.

Former Intel Employee Indicted for Alleged Heist of $1B in Trade Secrets

This case involves employee theft of valuable intellectual property. Stealing and selling proprietary information has become big business. When proprietary information is stolen, a computer forensic investigator may work in tandem with corporate human resources and compliance professionals to help examine not only how the theft occurred, but also provide evidence for prosecution. This case shows that the FBI takes a tough line against stealing data from former employers.

In 2008, Biswamohan Pani, 33, a former Intel employee, was indicted for wire fraud and the theft of more than $1 billion worth of trade secrets from Intel. The stolen information was valued in research and development costs and included mission-critical details about Intel’s processes for designing its newest microprocessors. According to the affidavit, Pani told Intel management that he was resigning to work for a hedge fund and that he would use his accrued vacation until his termination date on June 11, 2008.

Pani remained on Intel’s payroll through June 11, 2008, but he started work at Intel rival Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (AMD) on June 2, 2008. From June 8 until June 11, 2008, Pani used his Intel laptop to access Intel’s servers and download commercially sensitive data, including more than 100 sensitive documents, 13 of which were classified by Intel as “Top Secret.” He also downloaded a document explaining how the encrypted Intel documents could be reviewed from an external hard drive after he left Intel. The indictment also alleged that Pani attempted to access Intel’s computer network again two days after his last day at Intel. On July 1, 2008, proprietary Intel documents were located at Pani’s home.

During his June 11 exit interview, Pani acknowledged his confidentiality obligations and falsely told Intel that he had returned all of Intel’s property, including any documents or computer data.

Per the indictment, AMD personnel neither requested the stolen information nor knew that Pani had taken or would take it. Pani may have planned to use the information to further his career, with or without his employer’s knowledge. Both Intel and AMD have assisted the FBI investigation.

If convicted, Pani faces up to 10 years on the trade secret charge, and an additional 20 years on each of the wire fraud counts.

See U.S. Department of Justice, Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS), http://www.justice.gov/usao/ma/Press%20Office%20-%20Press%20Release%20Files/Nov2008/PaniBiswamohanIndictmentPR.html. See also Secure Computing Magazine, September 18, 2008, http://www.securecomputing.net.au/News/123155,amd-worker-charged-with-intel-theft.aspx.

In this case, computer forensic evidence may include the date and time the files were downloaded as well as access information showing that Pani logged into the Intel servers. Time and date stamps are an important part of the computer forensic process. You will learn about these and other forensic techniques later in the book.

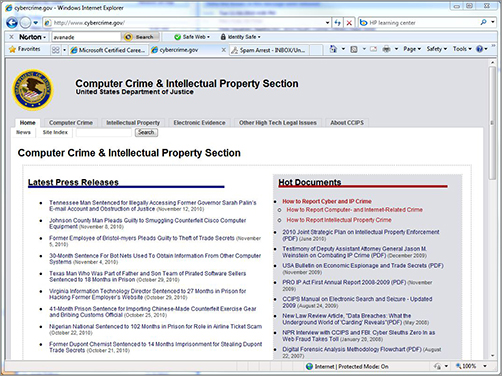

Figure 1-1 is from the Web site of the Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section of the Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (http://cybercrime.gov). Here you can find a lot of useful information and additional cases.

Figure 1-1: cybercrime.gov Web site (U.S. Department of Justice)

disaster recovery

The ability of an organization to recover from an occurrence inflicting widespread destruction and distress.

best practices

A set of recommended guidelines that outline a set of controls to improve internal and business processes, performance, quality and efficiency.

The following examples illustrate that computer forensic investigators have no idea where their cases will end up. As a computer sleuth, you may be required to work across state lines and with various agencies. You may end up working with several companies in various countries. You may wind up at a dead end because it takes too long to get the information you need or the employer decides not to prosecute. The computer forensic world is full of surprises.