CHAPTER 3

What We Need: The

Satisfaction Triangle

Has this ever happened to you? You are embroiled in an argument about a matter that is important to you and also to an employee. After several back-and-forth exchanges, you finally say, “Okay, then, we’ll do it your way.” You do what you can to give that employee exactly what he is asking for, only to find out later that he is still ticked off. You are left wondering, “What is his problem? Isn’t he ever satisfied?”

On the other hand, you may have had another experience as well. An employee storms into your office, upset about a policy that, as far as she is concerned, just isn’t working. You listen. She continues talking; you continue to listen. In the back of your mind, though, you are thinking, “I don’t know what we can do to fix that. It is what it is … nobody else has complained.” She keeps talking and you keep listening. Finally she looks at you with relief and says, “Thanks for listening. I feel better. I’ll talk to you later.” You didn’t do anything, and somehow the situation is now okay. You are left wondering what happened.

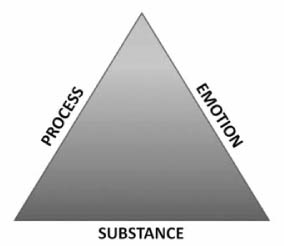

Usually in a conflict or disagreement, as we look for an acceptable solution, we focus on the substance of the outcome. Everyone wants something. The conventional wisdom tells us that getting that something means that the conflict is dissolved. Did you get what you asked for? If so, then you are happy. If you did not get what you wanted, then you are not happy. In the first scenario, your expectation is that, when you finally decide on a solution, the employee will be satisfied. In the second scenario, you do not expect the employee to leave your office satisfied unless you take some action that is acceptable to her. But the reality is often more complex than that. Just as important—sometimes more important—are the other two sides of the satisfaction triangle, shown in Figure 3-1: process satisfaction and emotional satisfaction. Understanding all three sides of the satisfaction triangle can provide managers with a more extensive set of tools for resolving conflicts.

Figure 3-1. Satisfaction triangle.

This example illustrates how all three sides of that triangle can contribute to satisfaction in a conflict. The final decisions that the group reached on budget allocations provided satisfaction on substance, though at the end of the process no one got all of what he or she wanted. Those long meetings they labored through, preparing charts and scrutinizing data, and sometimes arguing over specifics, answered their need for process satisfaction. Each person on the team understood how the decisions had been made, and where the final decisions came from. The respect for each other that they demonstrated in the midst of their disagreements and their willingness to listen to one another provided them with emotional satisfaction as well—each of them knew that he or she had been heard and had been treated with respect throughout the discussions, even as the meetings ground on and the outcome was elusive.

Substance Satisfaction

Satisfaction on substance is fairly easy to gauge. What are the answers? What are the solutions? What decisions are made? To adequately meet people’s needs for substantive satisfaction, try the following:

![]() Move beyond initial demands and positions. Why does each of us take these positions? What are our interests, objectives, or concerns?

Move beyond initial demands and positions. Why does each of us take these positions? What are our interests, objectives, or concerns?

![]() Manage expectations. Identify what people expect, clarify realistic and unrealistic expectations, lower expectations that are unreasonable.

Manage expectations. Identify what people expect, clarify realistic and unrealistic expectations, lower expectations that are unreasonable.

![]() Establish joint goals and common purpose. How does the question or disagreement relate to the work of the organization? Be clear that decisions ultimately are made to support the organization’s work, not for any other agenda.

Establish joint goals and common purpose. How does the question or disagreement relate to the work of the organization? Be clear that decisions ultimately are made to support the organization’s work, not for any other agenda.

When a problem is solved, when a solution is found that meets the needs and interests of those involved, this is a satisfying moment, indeed. In the experience of the executive team responding to the budget crisis, each member reported that the solution developed by the team was satisfactory—that is, it met enough of their needs and interests to be acceptable to all.

Several years ago, a client showed me an article citing research conducted in the early nineties through the University of Minnesota, involving interviews of people who had appealed their court decisions. Of the people who go to court and lose, a relatively small number decide to appeal the decisions. The researchers asked randomly selected individuals why they decided to go through the appeals process. After all, appealing a court decision is costly, time-consuming, and emotionally draining.

The findings showed that, among the people the researchers interviewed, far more than half did not really expect a different decision at the next higher level. Puzzled, the researchers asked, “Why, then, did you choose to appeal?” Their responses were about process satisfaction and emotional satisfaction. Some felt that the process as originally described to them was not what actually happened in court. Others said that the appeal itself was part of their right to due process. For still others, emotional satisfaction was more important: They did not feel that they had been heard at the lower court level or else they felt that they had been treated disrespectfully during the trial.

Process Satisfaction

Process satisfaction involves clarity about how decisions are made, knowing where you can have input, believing that the decisions are fair and consistent, and accepting that the standards for decision making apply to others the same way as they apply to you.

Consider two employees from different organizations, each interested in a promotion. In Organization A, an opening is posted and several people apply; three are internal, four are external. The criteria for the position are clearly described, application procedures are carefully delineated, and notice is circulated about the position several weeks before the deadline. Candidates are interviewed. When Jim is not selected, he is sent a letter thanking him for his application and providing some reasoning for the selection that was made. Jim is disappointed at not being selected, but satisfied that the process was fair and transparent. He recovers relatively quickly from the disappointment and refocuses on the job at hand.

In Organization B, no notice is given that there is a vacancy. The manager brings the new hire down the hall to introduce her to the rest of the staff. Jane is surprised: “How did she get that job? I have been working here for fifteen years. I know the computer system and our procedures, I know the history and all of the people we deal with. I will have to train her to do the job that I should have gotten. And I never knew about it!” Not only is Jane disappointed about not getting the promotion, but she is ticked off about the process itself. This employee expends considerable energy complaining to others about the new hire.

To provide process satisfaction, then:

![]() Be clear about how the decisions will be made, and who will make them.

Be clear about how the decisions will be made, and who will make them.

![]() Have policies and procedures for decision making, and follow them. There are many organizations that have created volumes of policies and procedures that are not followed or, worse, that are only applied occasionally. This approach opens managers up to accusations of favoritism.

Have policies and procedures for decision making, and follow them. There are many organizations that have created volumes of policies and procedures that are not followed or, worse, that are only applied occasionally. This approach opens managers up to accusations of favoritism.

![]() Be consistent in decision making across departments and among employees. This can be challenging in a large organization. Employees talk to other employees working in other divisions. When one supervisor allows his or her employees to have flexible schedules or alternate work schedules, word passes throughout the building faster than the flu. Other employees want the same advantages and opportunities. They expect fairness and consistency when these policies are interpreted for them. Establishing clear criteria for these decisions provides a transparent policy.

Be consistent in decision making across departments and among employees. This can be challenging in a large organization. Employees talk to other employees working in other divisions. When one supervisor allows his or her employees to have flexible schedules or alternate work schedules, word passes throughout the building faster than the flu. Other employees want the same advantages and opportunities. They expect fairness and consistency when these policies are interpreted for them. Establishing clear criteria for these decisions provides a transparent policy.

![]() Provide opportunities for input into decisions, and let people know when and how that information will be used.

Provide opportunities for input into decisions, and let people know when and how that information will be used.

Further exploring the importance of process satisfaction in the workplace, Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne identified three principles (the three Es) of fair process for employees:1

1. Engagement. When conflicts or problems arise, encourage input, allow others to question ideas, suggest their own remedies, or challenge proposals.

2. Explanation. Yes, it is the manager’s responsibility and authority to make decisions. When you have made a decision, close the loop. Clarify for employees the thought behind the decisions. Acknowledge their ability to understand by keeping them informed about your decisions. This acknowledgment demonstrates your respect for their efforts and expertise. It also allows them to let it go. Sometimes this is a step in process satisfaction that is too easy for a manager to overlook.

3. Expectation clarity. Be clear with employees about what is expected of them, what the “rules” are, what their areas of responsibility are, and the performance standards and penalties for failure. Giving people notice and fair warning is essential to maintaining process satisfaction. With clearly identified job expectations, you can then hold employees accountable for their work. And that accountability is seen as fair. Additionally, the wise supervisor is clear with an employee in assigning a project: an unambiguous description of what is expected, a due date or deadline, (sometimes) designated milestones to be met along the way, and criteria for acceptable project completion. She then asks the employee to describe back to her what the assignment is so that she can ascertain that the assignment is understood and clarify any confusion that may have occurred in their communication.

When you become aware of the importance of process satisfaction to the resolution of disputes, you will see opportunities for process satisfaction in many situations. During the budget crisis described above (the $9 million shortfall), team members met for long hours poring over tables and data. At the end of each meeting, they identified data gaps and other areas for analysis. At the next meeting, they returned with more information. One reason they reached an acceptable solution was that each understood and participated in the decision-making process. In the end, each knew where the decisions came from because they had participated in creating them.

On the other hand, process dissatisfaction can take a toll on employee morale—and productivity. Recently an employee explained to me his frustration with his supervisor. He had put in extra hours while his boss was on leave. The supervisor’s boss assured him, “Oh, yes, you can get overtime for this,” which he did. When the supervisor returned and gave him a similar assignment, she said, “You will get comp time for this, not overtime.” The employee’s perception was that the decisions made by his boss were arbitrary and capricious, that he couldn’t count on policies, or more importantly, on how the policies would be interpreted. When I met this employee, he was demoralized. “I’ll work eight hours a day, but I am leaving at 5:00. I am tired of being jerked around.”

Consider This

![]() Identify a conflict you have been a part of when a lack of clarity about the process contributed to the conflict.

Identify a conflict you have been a part of when a lack of clarity about the process contributed to the conflict.

![]() In this situation, what would have provided process clarity?

In this situation, what would have provided process clarity?

![]() Identify a policy or procedure within your organization that does provide process satisfaction when the outcome itself may not satisfy.

Identify a policy or procedure within your organization that does provide process satisfaction when the outcome itself may not satisfy.

Emotional Satisfaction

Emotional satisfaction really comes down to, “Was I heard?” and “Was I treated with respect?” Everyone needs to feel listened to, respected, and safe. If, in the process of looking at a problem, people feel threatened or discounted, they are far less likely to accept any decisions that are made.

If we go back to the budget-crisis example, note that members of the executive team respected one another. When one spoke, others leaned forward and listened. They did not always agree. In fact, on some points there was strong disagreement. But they maintained their commitment to each other to respect their differences of opinion and to listen to one another. To put it another way, emotional satisfaction was an integral part of their problem-solving approach.

At the beginning of this chapter I cited the example of a woman who came into your office worked up about a policy issue. From your perspective, “All I did was listen.” From her perspective, you respected her and her opinions enough to give her your time, to listen to her. That is just what she needed. To provide that emotional satisfaction, you need to:

![]() Create a safe place for difficult discussions. Some simple ground rules or guidelines can help: avoid personal attacks, keep an open mind, respect others’ opinions, speak for yourself.

Create a safe place for difficult discussions. Some simple ground rules or guidelines can help: avoid personal attacks, keep an open mind, respect others’ opinions, speak for yourself.

![]() Listen. Put aside your own thoughts and opinions. Turn away from the computer screen or the text message and give the person your undivided attention.

Listen. Put aside your own thoughts and opinions. Turn away from the computer screen or the text message and give the person your undivided attention.

![]() Respect confidentiality. If you tell people that you will keep a conversation confidential, you must keep your word. If you determine that the information really must be shared with someone else, be clear at the outset that you cannot maintain that confidentiality—and talk about whom you will be speaking with, what information you will pass along.

Respect confidentiality. If you tell people that you will keep a conversation confidential, you must keep your word. If you determine that the information really must be shared with someone else, be clear at the outset that you cannot maintain that confidentiality—and talk about whom you will be speaking with, what information you will pass along.

![]() Of course, people have emotions, even at work. Provide safe ways for them to be expressed and heard.

Of course, people have emotions, even at work. Provide safe ways for them to be expressed and heard.

Many times I have listened to a simple complaint that has taken on a life of its own within an office. “My supervisor doesn’t even say hello to me. When we pass each other in the hall, she doesn’t acknowledge that I exist.” That manager may be caught up in her own thoughts. More often, the manager may not realize how important a nod, a smile, or hello can be to a subordinate. The employee carries those experiences of recognition and acknowledgment into times of conflict and disagreement.

Consider This

![]() Identify an experience you have had during which someone listened to you. What effect did that have on you? What effect did it have on the conflict?

Identify an experience you have had during which someone listened to you. What effect did that have on you? What effect did it have on the conflict?

![]() When someone disagrees with you, are you able to put aside your own thoughts and hear what the person is saying?

When someone disagrees with you, are you able to put aside your own thoughts and hear what the person is saying?

Understanding the satisfaction triangle can give you a powerful tool as a manager, especially when you cannot give your employees substance satisfaction. What they are asking for simply cannot be done. The resources are not available. A request may have to be denied because of policy. To maintain the supervisor’s authority, the performance evaluation cannot be changed.

However, many times you can provide process satisfaction. You can develop clear processes and procedures for how decisions will be made, you can inform people of those processes, and then you can follow them. You can allow time for the employees to have input. When a decision is made, you must remember to close the loop: communicate what the decision is and explain what will be expected of them.

Virtually all the time, you can provide emotional satisfaction. The first step is to treat employees with respect—always. And when differences and disagreements arise, listen to what they have to say, and always treat them respectfully, even when you disagree.

Note

1. W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne, “Fair Process: Managing in the Knowledge Economy,” HBR on Point (Boston, Harvard Business School, 2003).