CHAPTER 5

How We Respond:

Approaches to

Conflict

When Sam gets an e-mail from his boss, giving him another assignment that is due this Friday, Sam reads the e-mail, shrugs to himself, and continues with the project he is working on.

When Tasha gets an e-mail from her boss, giving her another assignment that is due this Friday, she sighs, marks it down on her calendar, and scrambles to add it to her to-do list.

When Marvin gets an e-mail from his boss, giving him another assignment that is due this Friday, he picks up the phone and calls his boss to bargain. “I can’t get that project done on Friday, but if you can finish that report I am working on, I’ll get the new project mapped out so someone else can fill in the pieces.”

When Louisa gets an e-mail from her boss, giving her another assignment that is due this Friday, she calls him on the phone and explains, firmly and clearly, “I can’t possibly get that done by Friday. I already have a stack of work to do this week.”

When Bernie gets an e-mail from his boss, giving him another assignment that is due this Friday, he puts aside the report he is working on and goes into the boss’s office. “What do you need this project for? I need more information. And let me be clear with you about the projects I already have on my plate this week. Let’s see if we can devise a solution that works for you and for me.”

When we face differences and disagreements, we have choices about how we will respond to the situation. If you were to ask Sam, Tasha, Marvin, Louisa, or Bernie what their approach to that moment was, they may not be able to tell you. Each of them just responded in the way that made the most sense to them. We probably do not spend much time thinking about these choices; we may not even consider that we are making a choice. We respond in a way that we feel is comfortable and right for the situation. Most of us use only one or two approaches nearly all of the time.

Here is a short quiz that will help demonstrate the differences in these approaches. Picture yourself in the middle of a disagreement at work. Which of these statements sounds most like you?

1. I back off and let it go, even if it means that nothing is settled.

2. I prefer to do what others want for the good of the relationship.

3. I focus more on my goals and less on what others want.

4. Everyone should accept a little less than what he really wants so we can get on with the work.

5. I go to great lengths to understand what is important to others and to make sure they understand what is important to me.

Maybe the answer you give depends on whom you are having the disagreement with—your boss, your subordinates, or your peers or teammates. Maybe it depends on how important the disagreement is to you or to the office. Maybe it depends on other things going on in your life at the time, your mood, your health, the weather, the stock market, or what’s happening at home. This list cites five such patterns: avoiding, accommodating, driving, compromising, and collaborating.

Most of us have preferences and patterns for the choices we make. Sometimes our approaches work well. At other times, these patterns may be limiting and self-defeating. The people we work with have their own patterns and preferences, as well. As a manager, understanding your own approaches to conflict can help you make better decisions in how to respond to conflicts you face. Further, understanding more about the approaches of the people you supervise gives you additional tools to manage conflicts effectively.

Over the past thirty years, various authors have written about these different approaches people take.1 There are assessments available online that can help you identify your own preferences. One of the most accessible of these guides is Style Matters: The Kraybill Conflict Style Inventory at http://www.riverhouseepress.com.2

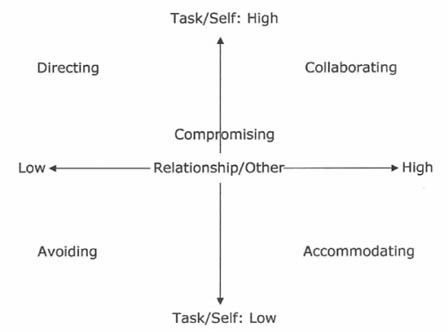

In this chapter I present in depth each of these five approaches to conflict listed above. Figure 5-1 is a visual way to understand these different approaches and their relationships to one another. The vertical axis represents concern or energy for one’s own goals (wants, needs, expectations), or the goals of the group one belongs to. The horizontal axis represents concern for the relationship or for the other person (or people), his or her wants, needs, and expectations. While the figure helps to explain and understand these differences, bear in mind that there are no distinct boundaries between these approaches.

Figure 5-1. Approaches to conflict.

![]() As you read the descriptions below, think about your own choices. When things are going smoothly, how are you inclined to respond?

As you read the descriptions below, think about your own choices. When things are going smoothly, how are you inclined to respond?

![]() How do you respond when tension rises in a disagreement? Does your reaction pattern shift?

How do you respond when tension rises in a disagreement? Does your reaction pattern shift?

There is no one right way to approach conflict. Each of these styles is appropriate in some circumstances, inappropriate in others. One challenge is to learn to use different approaches depending on different circumstances. As behavior specialist Abraham Maslow said, “When the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.”

Another dynamic to recognize is how your preferred style might shift when you are in a stressful situation.3 If your approach shifts dramatically when the tensions rise, you are likely to create confusion and distrust in those you work with. For instance, if your preferred style is accommodating under normal conditions, and your behavior shifts to directing when your anxiety rises, others are likely to be wary, finding your reactions unpredictable.

For each of the five approaches mentioned earlier, consider how that style can be an appropriate response to conflict. Then look at the downsides of overusing that style. Finally, for each approach, there are tips for working more effectively with another person who uses that approach.

Avoiding

The first example in the quiz, “I back off and let it go, even if it means that nothing is settled” is a statement of avoiding. It sits in the lower left-hand side of Figure 5-1: low energy for or attention to either the relationship or the task, as well as your own concerns. At times, there are good reasons to choose avoidance:

![]() Don’t sweat the small stuff. Let go of problems that, in the grand scheme of things, are just not that big a deal. Sometimes you have so many bigger problems to deal with that it’s better to let this one go. Suppose someone leaves a coffee cup in the office sink; it is easier to wash it out than to either chase down the culprit or create signage to hang over the sink.

Don’t sweat the small stuff. Let go of problems that, in the grand scheme of things, are just not that big a deal. Sometimes you have so many bigger problems to deal with that it’s better to let this one go. Suppose someone leaves a coffee cup in the office sink; it is easier to wash it out than to either chase down the culprit or create signage to hang over the sink.

![]() It’s just not worth it. You can spend a lot of energy banging your head against a brick wall, to no good end. Let it go—avoid the conflict. Suppose, for example, that when a new policy on comp (compensatory) time comes out, you as manager read it and groan. Now, you will have to explain to staff that the extra time they are putting in during this crunch won’t be compensated the way it was last year. People are not going to like it. They will complain, but there is nothing you can do about it. You don’t waste energy and effort trying to get the policy changed. You know from past experience that once something like that has been decided, the decision is final.

It’s just not worth it. You can spend a lot of energy banging your head against a brick wall, to no good end. Let it go—avoid the conflict. Suppose, for example, that when a new policy on comp (compensatory) time comes out, you as manager read it and groan. Now, you will have to explain to staff that the extra time they are putting in during this crunch won’t be compensated the way it was last year. People are not going to like it. They will complain, but there is nothing you can do about it. You don’t waste energy and effort trying to get the policy changed. You know from past experience that once something like that has been decided, the decision is final.

![]() Sometimes people need time to cool off. Or you need to cool off—or to get more information, or to consider what is going on, or to better understand what the problem might be. This is tactical avoidance; it is a short-term response, a postponement. You will revisit the conflict when you are better prepared.

Sometimes people need time to cool off. Or you need to cool off—or to get more information, or to consider what is going on, or to better understand what the problem might be. This is tactical avoidance; it is a short-term response, a postponement. You will revisit the conflict when you are better prepared.

On the other hand, some of us avoid problems, differences, and disagreements when the situation really needs to be addressed. A manager who always avoids conflict creates a very difficult workplace for everyone. For example:

![]() Small problems get bigger. Problems that start small or are manageable can grow into situations that are much harder to deal with—or even become insurmountable barriers. Avoidance seems like the best route to take—until a negative behavior becomes a pattern. For example, one coffee cup in the sink is a small thing; however, when staff consistently leave their dirty dishes stacked in the sink, expecting someone else to clean up their mess, the problem needs to be addressed.

Small problems get bigger. Problems that start small or are manageable can grow into situations that are much harder to deal with—or even become insurmountable barriers. Avoidance seems like the best route to take—until a negative behavior becomes a pattern. For example, one coffee cup in the sink is a small thing; however, when staff consistently leave their dirty dishes stacked in the sink, expecting someone else to clean up their mess, the problem needs to be addressed.

![]() The appearance of unfairness. Overuse of avoidance in the workplace can create significant difficulties. On survey after survey, the biggest complaint workers have is the perceived unwillingness of managers to take action against poor performers. Those who do pull their weight in the office, who are dependable and productive, watch another who is not held accountable. Their motivation and morale drop as they begin to wonder, “What is the point? Why am I expected to be responsible when others are not?”

The appearance of unfairness. Overuse of avoidance in the workplace can create significant difficulties. On survey after survey, the biggest complaint workers have is the perceived unwillingness of managers to take action against poor performers. Those who do pull their weight in the office, who are dependable and productive, watch another who is not held accountable. Their motivation and morale drop as they begin to wonder, “What is the point? Why am I expected to be responsible when others are not?”

![]() No paper trail. A manager who avoids confronting a poor performer often creates a difficult scenario. After weeks, or months, or even years, of not holding the employee accountable for the quality of his work or her tardiness, of avoiding the confrontation, and perhaps even of giving this person, year after year, positive performance reviews, the manager reaches a tipping point of exasperation, and calls the human resources office, wanting to terminate the employee. HR’s response? “You can’t fire this person. You have no justification in his personnel file.”

No paper trail. A manager who avoids confronting a poor performer often creates a difficult scenario. After weeks, or months, or even years, of not holding the employee accountable for the quality of his work or her tardiness, of avoiding the confrontation, and perhaps even of giving this person, year after year, positive performance reviews, the manager reaches a tipping point of exasperation, and calls the human resources office, wanting to terminate the employee. HR’s response? “You can’t fire this person. You have no justification in his personnel file.”

![]() No visible presence. I have worked with a few managers who seem to have perfected the ability to get from their own offices to the elevator without making contact with anyone else in the office—so, they never have any problems. At least, none that they can see. Others who work with them, however, are increasingly frustrated. Problems that could be resolved can’t even be raised.

No visible presence. I have worked with a few managers who seem to have perfected the ability to get from their own offices to the elevator without making contact with anyone else in the office—so, they never have any problems. At least, none that they can see. Others who work with them, however, are increasingly frustrated. Problems that could be resolved can’t even be raised.

Why do people avoid conflict even when avoiding as a technique is really not working for them? Often, it is fear: fear that their emotions will get out of control, or fear that they will hurt someone’s feelings, or someone will hurt theirs, or fear that they will do the wrong thing, or make a mistake. To move away from avoiding when you recognize a situation that you need to address, find ways to create a safe place for people to talk (see Chapter 13 for more detail):

![]() Set up a time to talk that allows both parties to express their ideas and concerns.

Set up a time to talk that allows both parties to express their ideas and concerns.

![]() Find a neutral place. If you are having a difficult discussion with an employee, come out from behind your desk. Talk over a conference table, or consider a more informal setting.

Find a neutral place. If you are having a difficult discussion with an employee, come out from behind your desk. Talk over a conference table, or consider a more informal setting.

![]() Allow people (yourself included) time to think through their responses or decisions.

Allow people (yourself included) time to think through their responses or decisions.

![]() Develop guidelines for the discussion so everyone knows what behavior is expected from one another. Simple statements like, “One person talk at a time” or agreeing to listen to one another can set a tone for productive discussion.

Develop guidelines for the discussion so everyone knows what behavior is expected from one another. Simple statements like, “One person talk at a time” or agreeing to listen to one another can set a tone for productive discussion.

![]() Establish a common goal or purpose. Clearly state the problem to be solved, or question to be answered, rather than state the answer you want someone to agree to.

Establish a common goal or purpose. Clearly state the problem to be solved, or question to be answered, rather than state the answer you want someone to agree to.

![]() Stay focused on issues, not on personalities or on assigning blame.

Stay focused on issues, not on personalities or on assigning blame.

If you are working with an avoider, alert the individual early on to potential problems or issues that may need to be addressed. Also, give the person time to think and consider, rather than demanding an answer in the moment.

Consider This

![]() Do you find yourself avoiding conflict more often than you’d like? Are there problems you can’t talk about? People you avoid?

Do you find yourself avoiding conflict more often than you’d like? Are there problems you can’t talk about? People you avoid?

![]() Are there conversations you are not having?

Are there conversations you are not having?

If so, identify the steps you will take to address one issue that needs attention.

Accommodating

In the short quiz at the beginning of the chapter, the second response “I prefer to do what others want for the good of the relationship,” is about accommodating. In the lower right-hand corner of the chart (Figure 5-1), accommodating places higher importance on “the other” or “for the group” than for what may be “important to me.”

There is a lot that is positive about accommodation as a strategy:

![]() Accommodating behavior often springs from feelings of compassion and empathy: “Their needs are great, my needs are small. What can I do to help?” For example, when Tom’s young daughter was diagnosed with leukemia, others in the office stepped in to cover his workload, no questions asked. The needs, expectations, or goals of the group are more important than those of the individual. Being a team player often means putting aside your own desires for the greater good of the whole group.

Accommodating behavior often springs from feelings of compassion and empathy: “Their needs are great, my needs are small. What can I do to help?” For example, when Tom’s young daughter was diagnosed with leukemia, others in the office stepped in to cover his workload, no questions asked. The needs, expectations, or goals of the group are more important than those of the individual. Being a team player often means putting aside your own desires for the greater good of the whole group.

![]() Sometimes accommodating can be like money put in the bank. “What you are asking for here is important to you, less important to me.” There is a spirit of cooperation within the office. When one employee has a daunting deadline looming, another person will offer to help out. So accommodating others sometimes gives you the leeway to ask for favors in the future. With team spirit, there is an unspoken expectation that favors will be reciprocated down the road.

Sometimes accommodating can be like money put in the bank. “What you are asking for here is important to you, less important to me.” There is a spirit of cooperation within the office. When one employee has a daunting deadline looming, another person will offer to help out. So accommodating others sometimes gives you the leeway to ask for favors in the future. With team spirit, there is an unspoken expectation that favors will be reciprocated down the road.

![]() Customer service is all about accommodating the customer. “What can we do to help?” “Certainly, we’ll take care of that right away.” My boss, other departments, and different offices in the organization have needs and requests, as do external customers. It is your job to respond, to deliver, to give them what they need when they need it.

Customer service is all about accommodating the customer. “What can we do to help?” “Certainly, we’ll take care of that right away.” My boss, other departments, and different offices in the organization have needs and requests, as do external customers. It is your job to respond, to deliver, to give them what they need when they need it.

There are limits to accommodating, however:

![]() Unlimited accommodating can’t be sustained over time. You run out of resources or energy to take on every task that is requested or expected of you.

Unlimited accommodating can’t be sustained over time. You run out of resources or energy to take on every task that is requested or expected of you.

![]() Sometimes, accommodating just encourages others to take advantage. Then, they don’t take responsibility for their own work.

Sometimes, accommodating just encourages others to take advantage. Then, they don’t take responsibility for their own work.

Why do people overuse accommodation as a response to conflict? Why do they allow their high concern for the relationship to override their own interests? The manager or supervisor who is desperate to be liked by her subordinates can slip into accommodation mode more often than is healthy for the organization, failing to hold staff accountable for their time or work products. “I want you to like me” “I want you to see me as a good person … a good worker … a good boss … a good guy.” Likewise, the subordinate who is too accommodating to the boss risks burnout and resentment as the assignments keep piling up.

A manager can also overuse accommodation when dealing with his or her own superiors or the external customers, committing the staff to more tasks than they can handle, and thereby losing sight of the priorities he or she has already established for the team. The result may be promises that cannot be kept, staff burnout, and important priorities not receiving adequate attention.

Consider This

![]() Do you find yourself saying, “Yes, I can do that” when in your heart you are saying “No, I can’t possibly take on one more thing”?

Do you find yourself saying, “Yes, I can do that” when in your heart you are saying “No, I can’t possibly take on one more thing”?

![]() Do you hear someone’s request with some agitation: How could they be asking me to do that again? And still find yourself agreeing to the task?

Do you hear someone’s request with some agitation: How could they be asking me to do that again? And still find yourself agreeing to the task?

![]() If your answer is yes to these questions, identify one issue that is important to you. What strategy can you use to raise this issue without concern for damaging the relationship?

If your answer is yes to these questions, identify one issue that is important to you. What strategy can you use to raise this issue without concern for damaging the relationship?

If you find you are over-accommodating, try the following:

![]() Acknowledge the importance of the relationship.

Acknowledge the importance of the relationship.

![]() Identify the issue at hand that needs to be addressed.

Identify the issue at hand that needs to be addressed.

![]() Build the relationship so that, as future problems arise, you can work through them without fear of rejection.

Build the relationship so that, as future problems arise, you can work through them without fear of rejection.

![]() Learn to say no to a request, perhaps by giving the other person alternative solutions.

Learn to say no to a request, perhaps by giving the other person alternative solutions.

If you are working with a person who is a strong accommodator, try the following:

![]() Pay attention to the relationship, as well as to the issue at hand.

Pay attention to the relationship, as well as to the issue at hand.

![]() Ask nonconfrontational questions about the person’s concerns, preferences, and opinions.

Ask nonconfrontational questions about the person’s concerns, preferences, and opinions.

Living on the Bottom Half of the Chart

Working with an avoider or an accommodator can seem like a pretty good place to be—or at least it can feel comfortable for a while. With avoiders, you don’t have to talk about difficult issues because they never come up. As long as no one voices a complaint, there is no problem to solve. And with accommodators, you can get what you need. As long as you make it clearly known, the accommodator is ready and willing to comply. What is not seen, under the surface, is the simmering resentment that can come back to bite you in uncomfortable places. That resentment can lead to passive-aggressive behavior, or what we call “the grits factor.”

Sometimes people who overuse avoidance and accommodation resort to passive-aggressive behavior. What do we mean by passive-aggressive behavior? On the receiving end, you may know that something is not right, is not working, but you can’t quite put a finger on it. The passive-aggressive person may go to great lengths to avoid or to accommodate—or to appear to avoid or accommodate, while undermining your efforts or policies, hoping that you get the message or feel the pain. Since the issues that need to be addressed are not on the table, you can’t work together to find solutions, or even any way to move forward toward finding those solutions. The person’s anger and resentment grow—and are often fed by—his or her reluctance or inability to address difficult issues.

Passive-aggressive behavior can be pretty costly. On the factory floor, there is an expression, “malicious compliance.” Workers who are ticked off at management have the last word, “Yes, you can tell me to do this, and I will do it—and when it fails miserably, you won’t know who to blame.” Passive-aggressive behavior: you can’t get a firm grip on what is going on but you know that something is wrong.

On the other hand, it’s a lot like cooking grits. Some of us have cooked grits the old-fashioned way—not microwave grits, but the real kind, simmered on the stove in a pot. The process goes something like this: Bring the water to a boil. Slowly pour in the grits, stirring constantly to keep them from lumping. Turn down the heat, and continue to stir so the grits don’t stick to the bottom of the pot. Experienced grits cooks all know that, at this point, you must stand back from the pot. While the grits are simmering, they have an uncanny way of popping up in the most unexpected places, spitting bits up into the air. If you are not careful you will have boiling hot grits on your face.

Sometimes people who live in the world of avoidance and accommodation are like those grits in the pot. Suddenly they erupt in the most unlikely places. Wow! Where did that come from? He was always such a quiet guy. Well, “that” came from gobs of resentment that have been simmering over time, maybe years, until they pop up in your face. If you are working with someone who has these tendencies, it is in your best interest as a manager over the long haul to give the individual ways to be more open, honest, and forthcoming about voicing his or her concerns. There is more on this in Chapter 14, on listening.

Similarly, as a manager you may be guilty of passive-aggressive behavior. If you recognize your own tendency to hold onto resentments and engage in passive-aggressive behaviors or have blow-ups (like those grits), you can develop the necessary skills to become more direct with your employees, raising issues and addressing differences and needs as they arise. That kind of behavior change takes time and a lot of courage and commitment, but it can be done.

Consider This

![]() Do you see yourself sometimes engaging in passive-aggressive behavior?

Do you see yourself sometimes engaging in passive-aggressive behavior?

![]() Do you find yourself in the middle of a grits explosion, wondering yourself why you blew up so quickly?

Do you find yourself in the middle of a grits explosion, wondering yourself why you blew up so quickly?

Directing

In the short quiz at the beginning of the chapter, the third statement is about directing: “I focus more on my goals, and less on what others want.” Looking again at the Figure 5-1 chart, you’ll see that the vertical axis represents concern for oneself or for getting the task done. Directing is in the upper left-hand corner and represents high concern for what you want, need, or care about, or high concern for “getting it done,” and less concern for what others want, need, or care about. Directing is an appropriate approach sometimes, and it is inappropriate at other times. First, let’s see the many ways that directing is an appropriate response to disagreements and disputes:

![]() If you can state in clear terms what you want, need, or expect, you greatly enhance the possibility of getting what you need. A good manager will say, “Here are my priorities, here is why, thought through and listed.” When the manager clearly states the vision, the mission, the work to be done, the team appreciates the clarity and the direction they are being given.

If you can state in clear terms what you want, need, or expect, you greatly enhance the possibility of getting what you need. A good manager will say, “Here are my priorities, here is why, thought through and listed.” When the manager clearly states the vision, the mission, the work to be done, the team appreciates the clarity and the direction they are being given.

![]() Healthy directing brings out the best in each of us. When the office puts together a proposal for a project, many people expend a lot of effort. What does this project need? What do we bring to it? How can we deliver in a way that stands out against the others? The energy and the thought processes that go into this direction raise the standard for everyone.

Healthy directing brings out the best in each of us. When the office puts together a proposal for a project, many people expend a lot of effort. What does this project need? What do we bring to it? How can we deliver in a way that stands out against the others? The energy and the thought processes that go into this direction raise the standard for everyone.

![]() Solid direction—even a good argument—can bring everyone closer together. This has been a huge lesson for me about conflict. That is, going toe-to-toe with someone who matters to you (boss, subordinates, or coworkers), and working through a difficult issue shows you that the other person will stick with you through it. You demonstrate your commitment to the work and to each other by engaging one another fairly. Likewise, you are still working together, often better than ever before, because you understand each other and you are assured of mutual loyalty to the mission and goals.

Solid direction—even a good argument—can bring everyone closer together. This has been a huge lesson for me about conflict. That is, going toe-to-toe with someone who matters to you (boss, subordinates, or coworkers), and working through a difficult issue shows you that the other person will stick with you through it. You demonstrate your commitment to the work and to each other by engaging one another fairly. Likewise, you are still working together, often better than ever before, because you understand each other and you are assured of mutual loyalty to the mission and goals.

On the other hand, there is danger in always being in directing mode. A person who is always directing, who lives by the axiom “My way or the highway,” creates unnecessary challenges for him- or herself and for everyone else as well. Here are some of the downsides of always being in competitive mode:

![]() People who are always in competitive mode are often fixated on being right. Other people’s ideas are not solicited or considered. When others raise concerns or questions, they can be shut down immediately.

People who are always in competitive mode are often fixated on being right. Other people’s ideas are not solicited or considered. When others raise concerns or questions, they can be shut down immediately.

![]() Or one person (sometimes the boss) takes credit for the work of the entire team. As he or she briefs higher-ups at the conclusion of the project, the report sounds as if that person completed the project single-handedly. All the work that the team has done is disregarded.

Or one person (sometimes the boss) takes credit for the work of the entire team. As he or she briefs higher-ups at the conclusion of the project, the report sounds as if that person completed the project single-handedly. All the work that the team has done is disregarded.

![]() Every disagreement can become a win-lose contest, with the competitive person committed to winning no matter what the cost. Sometimes this strong commitment to winning at the other’s expense degenerates even further to lose-lose: “Maybe I’ll feel some pain, but if I can make you lose more than me, it will be worth it.” As Coach Vince Lombardi famously said, “Winning isn’t everything. It’s the only thing.” This works really well for a football team, but in working relationships the “losers” do not simply walk away from the game. In disagreements or conflicts, over time the others who are not being heard or acknowledged for their contributions, or who are made to feel inept or unvalued, start looking for ways to even the score.

Every disagreement can become a win-lose contest, with the competitive person committed to winning no matter what the cost. Sometimes this strong commitment to winning at the other’s expense degenerates even further to lose-lose: “Maybe I’ll feel some pain, but if I can make you lose more than me, it will be worth it.” As Coach Vince Lombardi famously said, “Winning isn’t everything. It’s the only thing.” This works really well for a football team, but in working relationships the “losers” do not simply walk away from the game. In disagreements or conflicts, over time the others who are not being heard or acknowledged for their contributions, or who are made to feel inept or unvalued, start looking for ways to even the score.

![]() The manager needs the support of others to implement ideas. If you are always in competitive mode, you will find pretty quickly that you are hanging out there by yourself. Others may become hostile and combative, or give up and withdraw. Or, as one of my favorite baseball caps says, “I’m their leader; which way did they go?”

The manager needs the support of others to implement ideas. If you are always in competitive mode, you will find pretty quickly that you are hanging out there by yourself. Others may become hostile and combative, or give up and withdraw. Or, as one of my favorite baseball caps says, “I’m their leader; which way did they go?”

Consider This

![]() Are you eager to confront—so eager that others may back away from working with you, or avoid discussions with you?

Are you eager to confront—so eager that others may back away from working with you, or avoid discussions with you?

![]() Do you insist on having the last word?

Do you insist on having the last word?

![]() How important is winning to you?

How important is winning to you?

If you see yourself using this style too often, identify one disagreement and commit to using the solution-seeking model in Chapter 13, “Reaching Agreement.”

If you see yourself being overly competitive, try the following:

![]() Slow down.

Slow down.

![]() Rather than rush to give the answer, or give directives, practice listening; become curious about others’ ideas and views. You will find less resistance to your own ideas when you can take others’ views into account.

Rather than rush to give the answer, or give directives, practice listening; become curious about others’ ideas and views. You will find less resistance to your own ideas when you can take others’ views into account.

People who are always in directing mode want to be seen as competent, smart, and, above all, right. They want to be respected for who they are and what they know. How do you respond to someone who seems to be stuck in directing mode? Give them respect, and talk in terms of their interests. Both can go a long way toward opening up the competitor’s ears to what you have to say.

Similarly, demonstrate respect for who they are, what they know, and where they have been. You will read more on this topic in Chapter 15. Suffice it to say here that a person who is always in competitive mode wants to be seen as valued and worthy. Make certain that your tone of voice, your nonverbal communication, and your words convey that. At the same time, talk in terms of the other person’s interests. Talk about why what you have to say may be important. Think WIIFM— “What’s In It For Me”—from the other person’s perspective. Before you raise an issue, ask, “Why might he want to hear about what I have to say?” “What does she need from me?” This is the difference between “I need a raise” or “I deserve a raise,” and “Here is my value to you,” or “to the organization.”

Compromising

At the beginning of the chapter, the fourth statement was “Everyone should accept a little less than what they really want so we can get on with the work,” and this represents the compromising approach. On the Figure 5-1 chart, compromising is right in the middle. Yes, there is concern for what is important to you, as well as what is important to others, but in the interests of getting things done, everyone gives a little. I don’t get all of what I want. You don’t get all of what you want. We split the difference, meet somewhere in the middle. Traditional bargaining is one example of compromising, and it has several strengths to handling conflict:

![]() Compromise is useful when there are built-in limits to the resources available. The phrase that is often used in negotiation is “fixed pie.” If you are dealing with a fixed pie, a limited resource, compromise has the potential to give each party an acceptable partial resolution. For example, the management team working with the $9 million shortfall found themselves with limited resources—even more limited than they had imagined at the beginning of the year. Compromising was the approach they used to find a solution. After gathering as much information as they could, ultimately the group decided that each department could manage with something less than they had expected in order to come up with a viable answer to the budget problem.

Compromise is useful when there are built-in limits to the resources available. The phrase that is often used in negotiation is “fixed pie.” If you are dealing with a fixed pie, a limited resource, compromise has the potential to give each party an acceptable partial resolution. For example, the management team working with the $9 million shortfall found themselves with limited resources—even more limited than they had imagined at the beginning of the year. Compromising was the approach they used to find a solution. After gathering as much information as they could, ultimately the group decided that each department could manage with something less than they had expected in order to come up with a viable answer to the budget problem.

![]() Compromising can yield a fairly quick, “good enough” answer. Suppose the front counter schedule was challenging for an auto service facility. With a limited staff and the need to offer coverage in the evening hours, the manager set a schedule that seemed to fairly distribute the workload, including the 6:00 to 9:00 P.M. time slot. Everyone worked one evening a week, a compromise that provided no one person would be responsible for handling this less desirable period.

Compromising can yield a fairly quick, “good enough” answer. Suppose the front counter schedule was challenging for an auto service facility. With a limited staff and the need to offer coverage in the evening hours, the manager set a schedule that seemed to fairly distribute the workload, including the 6:00 to 9:00 P.M. time slot. Everyone worked one evening a week, a compromise that provided no one person would be responsible for handling this less desirable period.

But, sometimes compromising doesn’t yield the best decisions. For example:

![]() People can be too quick to jump to an intermediate solution and get a less than satisfactory result. In the standard budgeting process, a small amount of money may not be adequate to accomplish anything meaningful. Rather than pursue decision making through compromise, whereby each component receives a small allocation, setting priorities and assigning the limited resources to a single project may achieve better results.

People can be too quick to jump to an intermediate solution and get a less than satisfactory result. In the standard budgeting process, a small amount of money may not be adequate to accomplish anything meaningful. Rather than pursue decision making through compromise, whereby each component receives a small allocation, setting priorities and assigning the limited resources to a single project may achieve better results.

![]() Compromising can become more of a game than a good decision-making tool. When we know that decisions will be made through compromise, we tend to raise our goals at the outset, anticipating the compromise and perhaps thwarting the process.

Compromising can become more of a game than a good decision-making tool. When we know that decisions will be made through compromise, we tend to raise our goals at the outset, anticipating the compromise and perhaps thwarting the process.

Consider This

![]() Are you sometimes in too much of a hurry to get an answer and move on?

Are you sometimes in too much of a hurry to get an answer and move on?

![]() Might you be missing important information that could help everyone get to a better solution?

Might you be missing important information that could help everyone get to a better solution?

To move away from too much dependence on compromising, to keep from smacking your forehead later for missing a more comprehensive, less obvious solution, slow down. Get more information before thinking about an answer. Explore the possibilities. Find out what is important to the parties involved. Discover what is important to you—what this decision is really about—before making the decisions.

Collaborating

In the beginning of this chapter, the fifth statement was “I go to great lengths to understand what is important to others, and to make sure they understand what is important to me”; this statement describes the approach of collaborating. On the Figure 5-1 chart, collaborating is placed in the upper right-hand corner. It translates to high concern for what you and the relationship, as well as high concern for what is important to others. Breaking the word collaboration down to its parts, it is easy to see the “co-labor” in it—or, working together. In collaborating mode, both parties first spend time understanding the situation from both perspectives, then together they build a solution that works for both. When both the relationship and the decision are of high importance, taking the time that collaborating requires is well worth the effort.

The positive side of collaborating behavior is obvious:

![]() Everyone has his or her needs and expectations met. For instance, in the earlier example of the auto service front-counter schedule problem, the manager consulted each member of the staff about his or her preferences and personal situations. One member was taking classes at the local college, giving him a split shift through the week around his classes, and the evening hours every day really would work well for him. Another employee was juggling child care and her husband’s work schedule, and coming in later and working later each evening would work well with her. The solution was achieved through collaboration.

Everyone has his or her needs and expectations met. For instance, in the earlier example of the auto service front-counter schedule problem, the manager consulted each member of the staff about his or her preferences and personal situations. One member was taking classes at the local college, giving him a split shift through the week around his classes, and the evening hours every day really would work well for him. Another employee was juggling child care and her husband’s work schedule, and coming in later and working later each evening would work well with her. The solution was achieved through collaboration.

![]() Collaborating on a solution builds support for the decision. By working together to find a solution, both your needs and the others involved are appropriately met. When everyone leaves the room, people have a stronger commitment to implementing your decision. Each has ownership for problem solving when anyone hits a stumbling block.

Collaborating on a solution builds support for the decision. By working together to find a solution, both your needs and the others involved are appropriately met. When everyone leaves the room, people have a stronger commitment to implementing your decision. Each has ownership for problem solving when anyone hits a stumbling block.

![]() Collaborating builds the relationship. Building a mutually beneficial solution through collaboration requires listening to one another and respecting each other’s views and opinions. When you engage in this approach, the trust bond among manager and staff is strengthened. When there is another disagreement, you all engage one another in finding a solution because finding the last solution went so well.

Collaborating builds the relationship. Building a mutually beneficial solution through collaboration requires listening to one another and respecting each other’s views and opinions. When you engage in this approach, the trust bond among manager and staff is strengthened. When there is another disagreement, you all engage one another in finding a solution because finding the last solution went so well.

When I first saw the Figure 5-1 chart, I naively thought that collaboration was the answer to all of the world’s problems. We talk until we find a solution that meets your interests, needs, and expectations as well as mine. But when I applied my newfound enthusiasm to practical, real-life situations, I found that there were downsides to always collaborating all the time.

![]() Sometimes collaborating takes more time than the decision justifies. Perhaps you have attended those seemingly endless meetings, as I have, where everyone’s opinion is sought ad infinitum on a relatively trivial question, as everyone looks for a solution that will make everyone “happy.” What would make me happy at that point is for someone to make a decision so that we can get on to more important things.

Sometimes collaborating takes more time than the decision justifies. Perhaps you have attended those seemingly endless meetings, as I have, where everyone’s opinion is sought ad infinitum on a relatively trivial question, as everyone looks for a solution that will make everyone “happy.” What would make me happy at that point is for someone to make a decision so that we can get on to more important things.

![]() Sometimes collaborating may take more time than anyone has. In an emergency or a crisis, the leader needs to give directions so that staff can take action.

Sometimes collaborating may take more time than anyone has. In an emergency or a crisis, the leader needs to give directions so that staff can take action.

![]() Sometimes the manager is reluctant to step in and make a tough decision, preferring to rely on a collaborative approach for fear of making a mistake. But making a decision too slowly in the search for consensus can be a bigger mistake.

Sometimes the manager is reluctant to step in and make a tough decision, preferring to rely on a collaborative approach for fear of making a mistake. But making a decision too slowly in the search for consensus can be a bigger mistake.

![]() Collaborating can be used to avoid making any decision at all. “We’ll wait until everyone agrees,” becomes another way of saying, “We’re not going to make any decision.”

Collaborating can be used to avoid making any decision at all. “We’ll wait until everyone agrees,” becomes another way of saying, “We’re not going to make any decision.”

![]() Collaborating simply may not be possible. Where the disagreement or conflict is over limited resources, there may be no way to “expand the pie,” to build a solution that answers everyone’s needs.

Collaborating simply may not be possible. Where the disagreement or conflict is over limited resources, there may be no way to “expand the pie,” to build a solution that answers everyone’s needs.

By the way, I don’t use the term win-win when discussing collaboration. It is a popular phrase, but it can mislead people into expecting to win—getting back into that mode of “winning” at all costs. Decision making is often more complicated than win-win.

Consider This

![]() Do you sometimes agonize over getting to a decision—looking for everyone’s agreement before moving forward?

Do you sometimes agonize over getting to a decision—looking for everyone’s agreement before moving forward?

If you tend to overuse collaborating, the best solution is to create realistic deadlines for decision making. Solicit input from others, with the understanding that, if you can’t reach a solution together within this time frame, then you will make the decision. If you are working with someone who overuses collaboration, encourage the person to make decisions and provide deadlines.

Understanding these style differences in approaching conflict can help us to hear each other and respond to our differences more effectively. Remember, each person brings strengths as well as weaknesses to any decision-making process. In complex conflicts or disputes, resolution requires using each of these approaches appropriately along the way. As a manager, there will be times to clearly state and hold to your own needs and priorities, times to accommodate the needs of others, times when the only solution to a problem is to compromise, and times when you can work with others to achieve a collaborative answer.

Notes

1. Various authors have created similar charts for understanding these different approaches along a continuum of assertiveness and relationship, including Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann, Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (Tuxedo, NY: Xicom, 1974); and Robert Blake and Jane Mouton, The Managerial Grid (Houston: Gulf Publishing, 1964).

2. Ron Kraybill, Style Matters: The Kraybill Conflict Style Inventory (Harrisonburg, VA: Riverhouse Press, 2005).

3. Ibid, p. 12.