3

Value Creation in Buyer–Seller Relationships

This chapter focuses on one of the most important concepts in contemporary selling: value. Value-added selling sums up much of what securing, building, and maintaining customer relationships is all about. Taking advantage of the opportunity to really understand value and value creation will help you immensely as you move into the selling process chapters in Part Two of the book.

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- • Understand the concept of perceived value and its importance in selling.

- • Explain the relationship between the roles of selling and marketing within a firm.

- • Explain why customer loyalty is so critical to business success.

- • Recognize and discuss the value chain.

- • Identify and give examples for each category for communicating value in the sales message.

- • Understand how to manage customer expectations.

Adding Value is “Marketing 101”

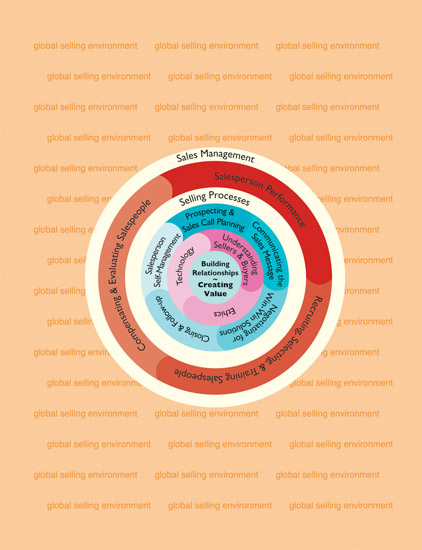

In chapter 1 we defined value as the net bundle of benefits the customer derives from the product you are selling and said that the communication of same is often referred to as a firm’s value proposition. It is up to the salesperson and the firm’s other forms of marketing communications to ensure the customer perceives these benefits as its value proposition. In transactional selling, the goal is to strip costs and get to the lowest possible sales price—in essence, the value proposition to the customer is low price. But relationship selling works to add value through all possible means, which is why we titled your book Contemporary Selling: Building Relationships, Creating Value and why we placed the elements of building relationships and creating value at the core (center circle) of the Model for Contemporary Selling.

Value-added selling changes much of the sales process. As you will see in this chapter, the sources of value (or, more properly, perceived value, meaning that whether or not something has value is in the eyes of the beholder—the customer) are varied. Moving to more value-added approaches to selling is not easy, and selling value is the single biggest challenge faced by sales professionals.1

Why a chapter focused solely on value? Two simple reasons: (1) The evidence is clear that success in selling depends greatly on the degree to which customers perceive that they achieve high value from a vendor relationship, and (2) many salespeople have trouble making a shift from selling price to selling value.

Role of Selling in Marketing

A good place to start understanding the role of value is with a brief review of marketing and the role of selling within marketing. For years, introductory marketing textbooks have talked about the marketing concept as an overarching business philosophy. Companies practicing the marketing concept turn to customers themselves for input in making strategic decisions about what products to market, where to market them and how to get them to market, at what price, and how to communicate with customers about the products. These 4 Ps of marketing (product, place or distribution, price, and promotion) are also known as the marketing mix. They are the toolkit marketers use to develop marketing strategy.

Personal selling fits into the marketing mix as part of a firm’s promotion mix, or marketing communications mix, along with advertising and other elements of the promotional message the firm uses to communicate the value proposition to customers. Other available promotional vehicles are sales promotion, including coupons, contests, premiums, and other means of supporting the personal selling and advertising initiatives; public relations and publicity, in which messages about your company and products appear in news stories, television interviews, and the like; and direct marketing, which might include direct mail, telemarketing, electronic marketing (via website or email or social media), and other direct means.2

These elements of marketing communications are referred to as a “mix” to emphasize that, when developing a strategy and budget for marketing communications, companies must decide how to allocate funds among the various promotional elements.

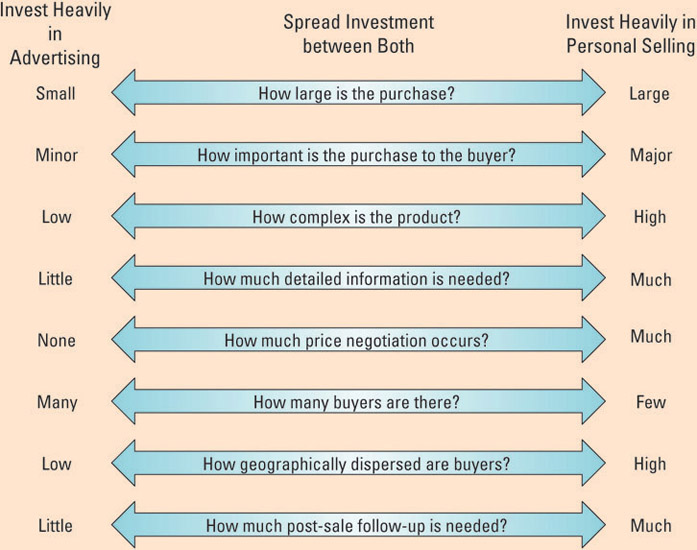

Several factors may affect the marketing communications mix, as shown in Exhibit 3.1. The size and importance of the purchase, complexity of the product, how much information buyers need, degree of price negotiation, number and dispersion of buyers, and whether postpurchase contact is required all drive decisions about the marketing communications mix.

To ensure that the message about a company and its products is consistent, the firm must practice integrated marketing communications (IMC), as opposed to fragmented (uncoordinated) advertising, publicity, and sales programs. IMC is very important to selling, as it keeps the message about the value proposition consistent, which in turn supports the overall brand and marketing strategy. Key characteristics of effective IMC programs are:

- IMC programs are comprehensive. All elements of the marketing communications mix are considered.

- IMC programs are unified. The messages delivered by all media, including important communications among internal customers (people within your firm who may not have external customer contact but who nonetheless add value that will ultimately benefit external customers) are the same or support a unified theme.

- IMC programs are targeted. The various elements of the marketing communications mix employed all have the same or related targets for the message.

- IMC programs have coordinated execution of all the communications components of the organization.

- IMC programs emphasize productivity in reaching the designated targets when selecting communication channels and allocating resources to marketing media.3

FedEx has been very successful at IMC, in both B2B and B2C markets. This is important, since the core of FedEx’s business is adding value through high-priced but fast and dependable service. To achieve this, internally all employees are trained to behave as though they have customers whether they actually interface with external users or not. That is, various departments within FedEx practice relationships-building among each other. Good internal marketing provides a consistency of message among employees and shows that management is unified in supporting FedEx’s key strategic theme of adding value through reliability. Externally, FedEx uses all the elements of the marketing communications mix—advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, public relations/publicity, and various methods of direct marketing, including a strong web and social media presence. FedEx is careful to communicate its value proposition consistently via each element of the mix.

Exhibit 3.1 Factors Affecting the Marketing Communications Mix

Role of Marketing in Selling

You just saw that selling plays a crucial role in the success of marketing strategy. But how do things work in the other direction—that is, how does marketing affect selling? As we discussed, the marketing communications mix (or promotion mix) is one element of the overall marketing mix that a firm uses to develop programs to market its products successfully. Products may be physical goods or services. Some firms market primarily services (such as insurance companies), while others market both goods and accompanying services (such as restaurants).

We know that the marketing mix consists of the famous 4 Ps of marketing: product, place (for distribution, or getting the product into the hands of the customer), price, and promotion (marketing communications). Like the elements of the marketing communications mix, each element of the marketing mix plays a large part in forming and communicating the overall bundle of benefits that a customer ultimately will perceive as the value proposition. This is why salespeople benefit from a well-executed marketing mix strategy.

Marketing also has an important role in gaining input and ultimate buy-in from the sales force on marketing strategies. The best way to do this is to involve salespeople and their managers in the marketing planning process from the ground up. Also, good communication lines must always be open between sales and marketing so that salespeople can contribute their considerable insight gained “on the firing line” to marketers engaged in strategic market planning, product development, and all aspects of IMC strategy development and execution.4

In truth, salespeople hold incredible value for marketers. The knowledge shared by salespeople provides a more in-depth understanding of the marketplace and the customer that benefits marketing decision making. Leaders who encourage organization members within sales and marketing to build social connections between each other help to ensure that channels exist for the passage of important knowledge, which is a challenge in organizations where sales and marketing operate in a dysfunctional manner or a total vacuum relative to each other.5

Recently, there has been considerable talk of something of a “war” between sales and marketing in many organizations. That is, salespeople are from Mars; marketers are from Venus—the idea being that a variety of differences in the goals and roles of sales and marketing people create tension within a firm that can be a challenge to avoid and, if unchecked, can sub-optimize the customer’s experience. Strong executive leadership on the sales and marketing teams, coupled with an organizational culture of mutual respect for each role, can go a long way toward gaining crucial cooperation and collaboration between sales and marketing. Also, regular joint exercises in goal-setting and planning between sales and marketing are a key toward maximizing the customer’s experience with the firm and its offerings. Finally, identifying some performance metrics that both sales and marketing will be evaluated against greatly helps to promote a spirit of mutual focus on the customer’s experience.6

For example, nowadays marketing is directly responsible for generating an increasing number of leads for follow up by sales. Unfortunately, in too many cases sales fails to effectively follow up on the leads. This may be because of sheer volume or due to a perception that the lead quality is poor. To fix this, marketing and sales need to work together to establish better prequalification procedures and then prioritize the leads in the funnel so that sales doesn't feel that marketing is just throwing leads against the wall in quantity to see if they stick.7

At the end of the day, in order for an organization to do the best possible job of building relationships and creating value, sales needs marketing and marketing needs sales. Both groups must work together to make the customer’s experience with the firm and its offerings the very best experience possible.

Clarifying the Concept of Value

Later in the chapter we will discuss ways value can be created by a firm and communicated by its salespeople. First, however, let’s clarify a few issues related to value.

Value Is Related to Customer Benefits

Value may be thought of as a ratio of benefits to costs. That is, customers “invest” a variety of costs into doing business with you, including financial (the product’s price), time, and human resources (the members of the buying center and supporting groups). The customers achieve a certain bundle of benefits in return for these investments.

One way to think about customer benefits is in terms of the utilities they provide the customer. Utility is the want-satisfying power of a good or service. There are four major kinds of utility: form, place, time, and ownership. Form utility is created when the firm converts raw materials into finished products that are desired by the market. Place, time, and ownership utilities are created by marketing. They are created when products are available to customers at a convenient location, when they want to purchase them, and facilities of exchange allow for transfer of the product ownership from seller to buyer. The seller can increase the value of the customer offering in several ways:

- • Raise benefits

- • Reduce costs

- • Raise benefits and reduce costs

- • Raise benefits by more than the increase in costs

- • Lower benefits by less than the reduction in costs.8

Suppose you are shopping for a car and trying to choose between two models. Your decision to purchase will be greatly influenced by the ratio of costs (not just monetary) versus benefits for each model. It is not just pure price that drives your decision. It is price compared with all the various benefits (or utilities) that Car #1 brings to you versus Car #2.

Similarly, the value proposition a salesperson communicates to customers includes the whole bundle of benefits the company promises to deliver, not just the benefits of the product itself. For example, Dell Computer certainly communicates the customization and bundling capabilities of its PCs to buyers. However, Dell is also careful to always communicate its service after the sale, quick and easy access to their website, and myriad other benefits the company offers buyers. Clearly, perceived value is directly related to those benefits derived from the purchase that satisfy specific customer needs and wants.

For years, firms have been obsessed with measuring customer satisfaction, which at its most fundamental level means how much the customer likes the product, service, and relationship. However, satisfying your customers is not enough to ensure the relationship is going to last. In relationship-driven selling, your value proposition must be strong enough to move customers past mere satisfaction and into a commitment to you and your products for the long run—that is, a high level of customer loyalty. Loyal customers have lots of reasons why they don’t want to switch from you to another vendor. Those reasons almost always are directly related to the various sources of value the customer derives from doing business with you.

Loyal customers, by definition, experience a high level of satisfaction. But not all satisfied customers are loyal. If your competitor comes along with a better value proposition than yours, or if your value proposition begins to slip or is not communicated effectively, customers who are satisfied now quickly become good candidates for switching to another vendor. The reason building relationships with customers is so crucial to building loyalty is that its win-win nature bonds customer and supplier together and minimizes compelling reasons to split apart.9

The Value Chain

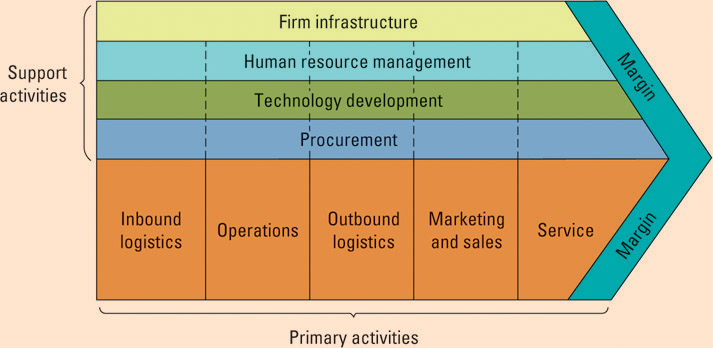

A famous approach to understanding the delivery of value and satisfaction is the value chain, envisioned by Michael Porter of Harvard to identify ways to create more customer value within a selling firm.10 Exhibit 3.2 portrays the generic value chain. Basically, the concept holds that every organization represents a synthesis of activities involved in designing, producing, marketing, delivering, and supporting its products. The value chain identifies nine strategic activities (five primary and four support activities) the organization can engage in that create both value and cost.

Exhibit 3.2 The Generic Value Chain

Source: Reprinted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster Adult Publishing Group, from Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, by Michael E. Porter. Copyright © 1985, 1998 by Michael E. Porter. All rights reserved.

The primary activities in the value chain are:

- • Inbound logistics—how the firm goes about sourcing raw materials for production.

- • Operations—how the firm converts the raw materials into final products.

- • Outbound logistics—how the firm transports and distributes the final products to the marketplace.

- • Marketing and sales—how the firm communicates the value proposition to the marketplace.

- • Service—how the firm supports customers during and after the sale.

The support activities in the value chain are:

- • Firm infrastructure—how the firm is set up for doing business. (Are the internal processes aligned and efficient?)

- • Human resource management—how the firm ensures it has the right people in place, trains them, and keeps them.

- • Technology development—how the firm embraces technology use to benefit customers.

- • Procurement—how the firm deals with vendors and quality issues.

The value-chain concept is very useful for understanding the major activities that can create value at the organizational level. CEOs in recent years have been working hard to align the various elements of the value chain, meaning that all facets of the company work together to eliminate snags that may impair the firm’s ability to secure, build, and maintain long-term relationships with profitable customers.

When the supplier’s value chain is working well, all the customer tends to see are the results: quality products, on-time delivery, good people, and so on. If the value chain develops just one weak link, the whole buyer–seller relationship can be thrown off. For example, a glitch in the value chain of one of Walmart’s vendors can delay delivery, resulting in stockouts in Walmart stores. If this happens repeatedly, it can damage the firms’ overall relationship. To reduce the potential for this happening, Walmart (which is known as a leader in implementing the value chain) requires all vendors to link with its IT system so that the whole process of order fulfillment is as seamless as possible.

Lifetime Value of a Customer

One element depicted in Exhibit 3.2 is margin, which of course refers to profit made by the firm. Back in chapter 1 we were careful to say that the goal of relationship selling is to secure, build, and maintain long-term relationships with profitable customers. If this seems intuitively obvious to you, that’s good. It should. In the past, many firms focused so much on customer satisfaction that they failed to realize that not every satisfied customer is actually a profitable one! Today, firms take great care to estimate the lifetime value of a customer, which is the present value of the stream of future profits expected over a customer’s lifetime of purchases. They subtract from the expected revenues the expected costs of securing, building, and maintaining the customer relationship. Exhibit 3.3 provides a simple example of calculating the lifetime value of a customer.

Selling to this customer is a money-losing proposition in the long run. Firms should not attempt to retain such customers. The analysis raises the prospects of firing a customer, which is a rather harsh way to express the idea that the customer needs to find alternative sources or channels from which to secure the products he or she needs. Of course, this assumes that other, more attractive customers exist to replace the fired one.11 Firms engaged in value-chain strategies who don’t pay attention to margin usually don’t stay in business long.

On the other hand, for profitable customers, increasing the retention rate—meaning keeping customers longer—by increasing loyalty can yield large increases in profits. This is because, as you can see from the calculations in Exhibit 3.3, it is much less costly to retain existing customers than it is to acquire new ones. Exhibit 3.4 shows the potential impact of customer retention on total lifetime profits in different industries. These issues are closely related to CRM, which will be discussed in chapter 5.

Quantifying the value proposition is an important element of successful selling. The Appendix (Selling Math) at the end of this chapter provides an approach, in spreadsheet format, to quantitative analysis of a product and its value to a customer.

Exhibit 3.3 Calculating the Lifetime Value of a Customer

| Estimated annual revenue from the customer | $15,000 |

| Average number of loyal years for our customers | ×5 |

| Total customer revenue | 75,000 |

| Company profit margin | ×10% |

| Lifetime customer profit | 7,500 |

| Less: Cost of securing a new customer | 3,500 |

| Cost of developing and maintaining the customer (est. 6 calls per year @ $500 each) | 3,000 |

| Average number of loyal years for our customers | ×5 |

| Total selling cost | 15,000 |

| Estimated costs of advertising and promotion per customer (from marketing department) | 500 |

| Lifetime customer cost | 15,500 |

| Lifetime value of the customer (lifetime profit – lifetime cost) | – $8,000 |

Exhibit 3.4 Impact of 5 Percent Increase in Retention Rate on Total Lifetime Profits from a Typical Customer

| Industry | Increase in Profits |

| Advertising agency | 95% |

| Life insurance company | 90% |

| Branch bank deposits | 85% |

| Publishing | 85% |

| Auto service | 81% |

| Auto/home insurance | 80% |

| Credit card | 75% |

| Industrial brokerage | 50% |

| Industrial distribution | 45% |

| Industrial laundry | 45% |

| Office building management | 40% |

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business School Press. From The Loyalty Effect, by Frederick Reichheld and Thomas Teal. Boston, MA. Copyright 2001 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, all rights reserved.

So far, we have looked at important issues of value creation from the perspective of the selling firm via the value-chain concept. In the next section, we identify specific value-creating factors the salesperson can communicate to the customer.

Communicating Value in the Sales Message

In the chapters in Part Two of the book we will discuss the process a salesperson follows to successfully communicate the sales message. But now we turn our attention to one of the most important content issues in selling: value proposition. In chapter 7 you will learn how to translate the idea of value into specific benefits to the buyer. To help you organize your thinking about value, now we focus on 12 broad categories from which you can draw these benefits in order to practice value-added selling. Keep in mind that it is customers’ perceptions of these factors that are relevant. For example, Toyota might have excellent product quality, but if this is not communicated to customers, they may not perceive it as excellent. The 12 categories for communicating value are:

- Product quality

- Channel deliverables (supply chain)

- Integrated marketing communications (IMC)

- Synergy between sales and marketing

- Execution of marketing mix programs

- Quality of the buyer–seller relationship (trust)

- Service quality

- Salesperson professionalism

- Brand equity

- Corporate image/reputation

- Application of technology

- Price.

Product Quality

David Garvin has identified eight critical dimensions of product quality that can add value.12

- • Performance. A product’s primary operating characteristics. For a car, these would be traits such as comfort, acceleration, safety, and handling.

- • Features. Characteristics that supplement the basic performance or functional attributes of a product. For a washing machine, they might include four separate wash cycles.

- • Reliability. The probability of a product malfunctioning or failing within a specified time period.

- • Conformance. The degree to which a product’s design and operating characteristics meet established standards of quality control (for example, how many pieces on an assembly line have to be reworked due to some problem with the output). Conformance is related to reliability.

- • Durability. Basically, how long the product lasts and how much use the customer gets out of the product before it breaks down.

- • Serviceability. Speed, courtesy, competence, and ease of repair for the product.

- • Aesthetics. How the product looks, feels, sounds, tastes, or smells.

- • Perceived quality. How accurately the customer’s perceptions of the product’s quality match its actual quality. In marketing, perception is reality.

For manufacturers of physical goods, product quality is the most fundamental of all sources of value. In the consumer health products space, the name Johnson & Johnson (J&J) has for years been synonymous with product quality. On every dimension listed above, J&J products have excelled. But over the past few years J&J experienced a raft of bad press about contamination in some of its most famous brands of over-the-counter medications. Bottles of tablets and capsules were reported by consumers as containing foreign elements that turned out to be residual materials from a lax production line. For J&J, like any manufacturer, news like this is devastating to its customer relationships—not just end users of the products like us, but also the many retailers that sell J&J products in stores around the globe. The sales force at J&J has been racked by multiple recalls that have left some shelves bare and retail customers scrambling to make up for lost sales and profits by promoting other manufacturers’ items in substitute. The lesson is that, in today’s competitive marketplace, one can never allow product quality to be compromised. At this stage, it remains to be seen if J&J will ever recoup the lost market share based on its highly publicized recent problems in this area.

Channel Deliverables (Supply Chain)

Firms that have excellent supply-chain management systems add a great deal of value for customers. A supply chain encompasses every element in the channel of distribution. FedEx is an organization that brings to its clients excellent supply-chain management as a key value proposition. FedEx salespeople, as well as FedEx’s overall IMC, constantly communicate this attribute to the marketplace.

Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC)

We have already seen how important integration of the marketing message is in managing customer relationships. When Lou Gerstner, former CEO of IBM, took the job, one of the first things he noticed as he visited various IBM field operations was that the image, message, and even the logo of IBM varied greatly from market to market. Such variance is almost always due to poor IMC. IMC starts with a firm’s people understanding and accepting its mission, vision, goals, and values. Then the message about the value proposition gets communicated to employees through internal marketing. Finally, it gets communicated to customers and other external stakeholders through all the elements of the promotion mix. Clients expect and deserve consistency in the way your value proposition is put forth. With great IMC, salespeople can refer to a well-known message about their firm that is all around to solidify the client relationship. IBM’s Gerstner put a great deal of emphasis on cleaning up the firm’s global IMC, which resulted in a clear and consistent message about what IBM stands for and how it delivers value to customers.

Synergy between Sales and Marketing

An easy definition of synergy is that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Sales and marketing exhibit synergy when they are both working together for the greater benefit of customers. The whole concept of our Model for Contemporary Selling centers on synergy—seamless organizational processes focused on managing customer relationships. When sales and marketing are out of sync, customers are marginalized and the value proposition is weakened. One way to ensure synergy is with cross-functional selling teams that include members of marketing in key roles.

Procter & Gamble is a firm that has put a great deal of energy into this issue. A vivid example of creating value through synergy is the way P&G develops its regular promotion schedule for its brands. Brand management works directly with field sales management to create a schedule and product mix for the promotions that best serve P&G’s clients. Thus, when a salesperson presents a new promotion to a customer, he or she can sell the value of the thoughtful planning that took into account the customer’s needs and wants in making P&G’s promotional decisions.

One important facilitator of synergy between sales and marketing is the use of dashboards by both teams. You will read more about dashboards in Chapter 5, but for now the concept in a nutshell is that marketing and sales agree on a prioritized shortlist of metrics that will be captured and displayed so that members of each group can easily track progress. Often firms display the dashboard as a homepage on a laptop or tablet. Incentives can be offered for salespeople to gather and report information in support of the dashboard elements.13

Execution of Marketing Mix Programs

Firms that do a great job of integrating the marketing mix provide opportunities for value-added selling. Salespeople enjoy communicating with clients about their firm’s plans for product changes, new-product development, and product line extensions. And a history of a strong marketing mix program gives salespeople and the firm credibility that helps turn prospects into new customers. Thus, customers have confidence that your firm will support its products through effective marketing mix programs.

Quality of the Buyer–Seller Relationship (Trust)

A key issue in relationship quality is trust. Trust is a belief by one party that the other party will fulfill its obligations in a relationship.14 Obviously, building trust is an essential element of selling. It represents confidence that a salesperson’s word (and that of everyone at his or her company) can be believed. It signifies that the salesperson has the customer’s long-term interests at the core of his or her approach to doing business. An atmosphere of trust in a relationship adds powerful value to the process.

The value of trust for salespeople is heightened when they are focusing on selling more comprehensive and in turn complex solutions to other organizations. In the critical relationship initiation stage, the greater the intangibility or complexity of what is being offered by the selling organization the greater the need for trust is on the part of the buying organization. This is because intangible products and complex products inherently increase risk perception on the part of buyers.15

Service Quality

Ethical Dilemma ![]()

Handling a Declining Account

Ben Lopez has been with Bear Chemicals for seven years and has earned a reputation as one of the best salespeople in the company. Starting as a detail salesperson calling on small specialty companies, he worked his way up to key account manager, calling on some of Bear’s largest customers.

Today, Ben was faced with a difficult decision. Midwest Coatings, Ben’s smallest account, called again this morning, wanting him to come out and talk about problems with its new manufacturing operations.

When Ben first started with the company, Midwest was Bear’s largest customer. However, over the last few years Midwest has become less competitive and has seen significant declines in its market share, with a corresponding reduction in the purchase of chemicals. Of even greater concern was the trend for foreign competitors to deliver higher-quality products at lower prices than Midwest.

Unfortunately, Midwest still views itself as Bear’s best customer. It demands the lowest prices and highest level of service. Its people call frequently and want immediate attention from Ben, even though Bear has customer support people (customer service engineers) to help with customer problems and service. For Ben, a growing concern is his personal relationship with several senior managers at Midwest. The chief marketing officer and several top people at Midwest are Ben’s friends and their children play with Ben’s kids.

After the phone call this morning, Ben called his boss, Jennifer Anderson, to get direction before committing to a meeting. He explained that the problems at Midwest were not Bear’s fault and a customer support person should deal with them by phone. Ben was worried that going out there would take an entire afternoon. He did not want to waste his time when a customer service engineer could handle the situation. Jennifer, who knew about the problems at Midwest, suggested it was time for a full review of the account. She also told Ben that it might be time to classify the company as a second-tier account, meaning Ben would no longer be responsible for calling on Midwest. While acknowledging the problems with Midwest, Ben is hesitant to lose the account because it might create personal problems for him at home.

Questions to Consider

- Should Ben drop Midwest as his account and let it become a second-tier customer?

- What obligation does a company have to customers who no longer warrant special service or attention?

Services are different from products. In particular, services exhibit these unique properties:

- • Intangibility. Services cannot be seen, tasted, felt, heard, or smelled before they are bought.

- • Inseparability. Unlike goods, services are typically produced and consumed simultaneously.

- • Variability. The quality of services depends largely on who provides them and when and where they are provided.

- • Perishability. Services cannot be stored for later use.

These unique properties of services create opportunities for firms to use them to add value to the firm’s overall product offerings and for salespeople to communicate this value to customers. Ethical Dilemma provides you with an interesting situation in which the future viability of service quality as a value-adding aspect of a customer relationship is called into question.

Because of the unique properties of services, it should not be too surprising that the dimensions of service quality are different from those for goods:

- • Reliability. Providing service in a consistent, accurate, and dependable way.

- • Responsiveness. Readiness and willingness to help customers and provide service.

- • Assurance. Conveyance of trust and confidence that the company will back up the service with a guarantee.

- • Empathy. Caring, individualized attention to customers.

- • Tangibles. The physical appearance of the service provider’s business, website, IMC materials, and the like.16

Nowadays, even when selling physical goods, these dimensions of service quality often trump other sources of value for customers (assuming no product quality problems, of course!).

Salesperson Professionalism

Your own level of professionalism in the way you handle yourself with customers is a great potential source of value to them. What is professionalism? It includes little things such as clear and concise correspondence, proper dress, good manners, and a positive attitude and can-do demeanor. Part Two of this book covers many aspects of how to exhibit professionalism as you go about relationship selling.

Brand Equity

Brand equity is the value inherent in a brand name in and of itself.17 Brand equity is a bit like the concept of goodwill on the balance sheet, since if a company liquidated all its tangible assets, a great brand would still add terrific value to the firm. Examples of brands with high equity are Coke, IBM, McDonald’s, and Apple. In selling, when all else is equal, your job is generally easier if you can sell the value of your brand. Global Connection builds an interesting case for salespeople developing their own personal global brand.18

Corporate Image/Reputation

Closely related to brand equity is the concept of how corporate image or reputation adds value. Some firms that have financial difficulties continue to gain new clients and build business simply based on their reputation. On the other hand, the perils of losing and then trying to regain company reputation are well documented. Many firms in the financial services sector saw their brands tarnished as they were blamed (rightly or wrongly) for contributing to the economic downturn that began in the late 2000s. It is demoralizing for a salesperson to have to represent a firm to customers when its name is in the press as a “bad guy.” Selling for an organization with a strong, positive image provides a leg up on competition, and the confidence that image brings to clients can overcome many other issues in making a sale.

Application of Technology

Some firms add substantial value to customer relationships through technology. Fortunately for the salesperson, communicating this value-adding dimension is usually quite straightforward. Pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Merck have developed sophisticated software for medical professionals that help them organize their daily jobs. Such activity is one example of strategic partnerships, which are more formalized relationships where companies share assets for mutual advantage. We’ll look more closely at value-adding technology in chapter 5.

Be your own Global Brand

What comes to mind when people see you? Or hear your name? That’s your personal brand. It’s the sum total of what people know about you—what they think of you after you’ve had a conversation, given a speech, or they’ve seen you in the public eye in some way. The idea is no different from what comes to mind when you see a product brand like Nike, Apple, or any global brand.

Every time you speak, you are branding yourself, and it’s important to think strategically about what and how you are delivering that message. Your conversations, presentations, emails, phone calls, and conversations in the hallway all send signals. Are you talking about big ideas? Are you clear, concise, and interesting? Do people appear to sit up and pay attention when you speak?

People have a feeling about others, almost as soon as they meet and work with them. They continue to shape that feeling with the more interactions they have. Pretty soon, they see them walking down the hall, and something registers, positive or negative. It’s within your power to make that feeling positive. What constitutes a strong personal brand? There are seven aspects of a powerful personal brand. A personal brand:

- • Is instantly recognizable

- • Stands for something of value

- • Builds trust

- • Generates positive word of mouth

- • Gives a competitive advantage

- • Creates career opportunities

- • Results in professional and financial success.

Wherever you are today in your professional life, you can start sending strong, positive signals that will cut through the clutter of day-to-day business and create a buzz about you. Everyone has the power to create their own positive personal brand. In fact, you could argue, they must if they want to succeed in a competitive global economy. It’s up to you to create the strategy and messages needed to create a buzz and a powerful brand.19

Questions to Consider

- Identify two or three great global brands. What do they do that makes them a great brand globally?

- Consider yourself as a brand in the context described above. What activities and steps can you take now to ensure that you will have a solid personal brand that will add value to your own career on a global basis?

Price

Now we are back to where we started in this chapter: price. As we said before, many salespeople have difficulty transitioning from selling price to selling value. You may be surprised to see price mentioned as a value-adding factor in selling. However, remember the discussion on value as a ratio of benefits to costs. For customers, value is the amount by which benefits exceed their investment in various costs of doing business with you (including the product’s price). And one of the ways we pointed out that you can increase value is by reducing costs (in this case, lowering price).

For some firms, low price is a key marketing strategy. Usually, such firms manage to compete on price by having consistently lower costs than competitors. The lower cost structure may have a number of sources, among them greater production efficiencies, lower labor costs, or a better supply-chain management system. Famously, Southwest Airlines has competed successfully for years using a low-cost strategy. Its operating efficiencies translate into not only lower prices but also better profit margins.

Sometimes firms feel relegated to competing on price because they see themselves as being in a commodity market. That is, their offering has no real differentiation from that of competitors and therefore a purely transactional selling approach is deployed (we discussed transactional selling in chapter 1). Put another way, the salesperson has none of the other value-adding sources above to bring to the customer. An interesting question that is more for a marketing strategy course than a selling course is how or if a firm can escape commoditization and find ways to strategically differentiate itself through some of the means above. For now, suffice it to say that transactional selling is unlikely to provide you with the kind of stimulating career opportunity we laid out in chapter 2 and it is not the approach that is the focus of this book.

Managing Customer Expectations

We have seen that salespeople can draw on a wide array of factors in communicating their firm’s value proposition. Each factor provides a rich context for communicating benefits to customers, a key topic in chapter 7. A final caveat deserves mention as we close our discussion of value. For any potential source of value or benefit, it is essential that the salesperson (and their firm) not overpromise and underdeliver. Instead, in relationship selling it makes sense to engage in customer expectations management and thus underpromise and overdeliver, which creates customer delight.

As we discussed in Chapter 1, customer delight—exceeding customer expectations to a surprising degree—is a powerful way to gain customer loyalty and solidify long-term relationships. Overpromising can get you the initial sale, but a dissatisfied customer will likely not buy from you again—and will tell many other potential customers to avoid you and your company. In executing the various selling process steps in Part Two of this book, remember the power of managing customer expectations.

Summary

Salespeople who really know how to communicate the value proposition to customers are well on their way to success. In selling, it is a customer’s perceptions of the value added that are key. Sales and marketing play major roles in communicating the value proposition. This message must be consistent in all forms in which it is communicated—hence the importance of integrated marketing communications (IMC).

Michael Porter’s value-chain concept provides a very useful model for understanding value creation at the firm level. At the salesperson level, we present a variety of categories from which a salesperson can draw to communicate various aspects of value as benefits to customers.

Key Terms

perceived value

marketing concept

4 Ps of marketing

marketing mix

promotion mix (marketing communications mix)

integrated marketing communications (IMC)

internal customers

internal marketing

utility

customer satisfaction

customer loyalty

value chain

margin

lifetime value of a customer

firing a customer

retention rate

supply-chain management

trust

brand equity

strategic partnerships

Before you begin

Before getting started, please go to the Appendix of chapter 1 to review the profiles of the characters involved in this role play, as well as the tips on preparing a role play.

Characters Involved

- Alex Lewis

- Abe Rollins

Setting the Stage

As part of a realignment of territories in District 10, Alex Lewis has just acquired a few customers from Abe Rollins. The realignment took place to better equalize the number of accounts and overall workload between the two territories, and both Alex and Abe welcome the change.

Unfortunately, one of Alex’s new accounts, Starland Food Stores, is giving him some problems. On his first call on buyer Wanda Green, she took the opportunity to hammer hard on Alex that (to quote) “The only thing that matters to me is price, price, price. Get me a low price and I will give you my business.” Alex knows that over the three years Abe called on Wanda, the two of them developed a strong professional relationship. Therefore, Alex gave Abe a call to see if they could get together over lunch to discuss how Alex might shift Wanda’s focus away from just price to other value-adding aspects of the relationship with Upland.

In truth, Upland is pretty competitively priced item-to-item versus competitors. However, it is definitely not the lowest-priced supplier, nor would Alex have the discretion to make special prices for Wanda.

Alex Lewis’s Role

Alex should begin by expressing his concern about Wanda’s overfocus on price as the only added value from Upland. He should be open to any insights Abe can provide from his experience on how to sell Wanda on other value-adding aspects of the relationship.

Abe Rollins’s Role

Abe should come into the meeting prepared to give a number of examples of how Alex (and Upland Company) can add value beyond simply low price. (Note: be sure the sources of added value you choose to put forth make sense in this situation.) Abe uses the time in the meeting to coach Alex on how he might be able to show Wanda that, while Upland’s products are priced competitively, they offer superior value to the competition in many other ways.

Assignment

Work with another student to develop a 7–10 minute exchange of ideas on creating and communicating value. Be sure Abe tells Alex some specific ways he can go back to Wanda with a strong value proposition on the next sales call.

Discussion Questions

- Select any firm that interests you. Which aspects of the 12 categories for communicating value you learned in the chapter do you believe are most relevant for the firm you selected, and why is each particularly important to that firm?

- What do you think are the most important ways sales can contribute to a firm’s marketing, and vice versa?

- Why is it so critical that marketing communications be integrated?

- What is customer satisfaction? What is customer loyalty? Is one more important in the long run than the other? Why or why not?

- Take a look at Exhibit 3.2 on the value chain. Pick a company in which you are interested, research it, and develop an assessment of how it is doing in delivering value at each link in the chain.

- Consider service quality as a source of value. Give an example of a firm of which you have been a customer that exhibited a high degree of service quality. Also, give an example of poor service quality you have experienced at a firm.

Mini-case 3 Bestvalue Computers

BestValue Computers is a Jackson, Mississippi, company providing computer technology, desktops, laptops, printers, and other peripheral devices to local businesses and school districts in the southern half of Mississippi. Leroy Wells founded BestValue shortly after graduating from college with an Information Technology degree. Leroy began small, but soon collected accounts looking for great value at reasonable prices with local service. When Leroy started his business in Jackson, he believed that anyone could build a computer. In fact, other than the processor and the software that runs computers, many of the components used are sold as commodities.

Leroy initially viewed his company as a value-added assembler and reseller of technology products. This business model was so successful that Leroy decided to expand from Jackson throughout southern Mississippi. To facilitate this expansion, Leroy hired Charisse Taylor in Hattiesburg to sell his products to all of south Mississippi, including the Gulf Coast, where a number of casinos were locating.

Before hiring Charisse, Leroy made sure that she had a reputation for developing long-term relationships with her customers and that she was a professional with integrity. Charisse did not disappoint Leroy. She has grown the business significantly in the two years that she has been with BestValue. Charisse credits her success to being honest with customers, which includes explaining exactly what BestValue can provide in terms of software and hardware. That way, no one is surprised with the result. In fact, many times customers have remarked to both Charisse and Leroy that they received more than they expected.

Now Leroy has set his sights on the New Orleans and Memphis markets. In addition, many of his initial customers have grown beyond a couple of desktop computers. They are starting to ask Leroy if he can provide and service local area networks (LANs), which allow many computers to share a central server so that workers can share files and communicate much more quickly. Leroy has decided to pursue the LAN business because selling, installing, and servicing LANs seems to be a natural extension of his current business.

However, adding the LAN products and accompanying services to his existing line of business represents a big addition to his current method of operation, which is to provide high-quality, high-value computers and peripheral devices. This new venture into providing more of a service than a product seems somewhat risky to Leroy, but he recognizes that LANs are the wave of the future and that to remain viable he will have to start viewing his company as more of a service provider than a product provider.

To facilitate Leroy’s expansion into Memphis and New Orleans, he has hired two new salespeople. They are similar to Charisse in that they are relationship builders who believe providing clients with more than they promised is the key to successful selling today. This attitude is important because the competition in these two markets will be tough. Much larger competitors like Dell, IBM, and Hewlett-Packard have been selling equipment in these areas for a long time, so it will be very important for the sales reps to communicate BestValue’s message of great value, including reasonable prices and local service. In fact, Leroy realizes that the only way to compete with the big boys is to be better than they are, by providing value over and above what they offer. That philosophy has made BestValue a success so far, and Leroy thinks it will work in these new markets too.

Questions

- Identify and describe the categories of value creation on which BestValue currently relies most.

- How can BestValue utilize the service quality dimensions to make sure it is communicating a consistent message of high-quality service and value every time someone from the company interacts with a customer?

- Even though BestValue provides basically a commodity product, what role can the concept of brand equity play for BestValue’s sales reps as they begin contacting customers in the New Orleans and Memphis areas?

- What is the role of the BestValue sales reps in managing customer expectations? How can they ensure that new customers in the New Orleans and Memphis areas are delighted with their purchases? Be specific and explain.

- What are some dangers that BestValue must take into account as it moves into the new markets and begins to provide LAN products and services? How will value creation change for it with the addition of LANs?

Appendix: Selling Math

An important element in relationship selling is developing an effective and persuasive value proposition. In the vast majority of sales presentations a critical component of the value proposition involves a quantitative analysis of your product and its value to the customer. This Appendix, which we call Selling Math, provides the tools to develop the quantifiable justification for a value proposition. All of the spreadsheets discussed in this Appendix can be found at the website for Contemporary Selling (along with other important information). Please go to www.routledge.com/cw/Johnston and download the spreadsheets before you continue. Working through the spreadsheets as you read the Appendix is the best approach for understanding and applying Selling Math. In addition, the spreadsheets are interactive, so you can create your own scenarios and see how a change in one component of the analysis alters other elements.

Most quantitative analysis involves a spreadsheet and is usually in one of two formats:

- • If you are selling a product that is sold to a reseller (for example, a retailer), use the profit margin spreadsheet.

- • If you are selling a product or service that is used in the production of the business, use the return on investment (ROI) spreadsheet.

In customer relationship management (CRM) the customer value proposition is ascribed to one of three scenarios: (1) acquisition of new customers, (2) retention of existing customers, or (3) additional profitability (see Chapter 5). When creating a value proposition it is a good idea to identify which of these three is the most important objective in the presentation and create your spreadsheet around that goal. For example, if you were going to sell a new brand of clothing to a department store, you might argue that it would bring in new customers who are loyal current customers of the brand that had not shopped at the store previously. You might also argue it will increase retention by offering existing customers a larger selection which results in their greater satisfaction. Finally, you could argue the addition of the new brand would increase profitability because of the demand for the new product from existing and new customers, which would result in increased sales and profits. Analyzing the customer’s needs and then matching the company’s products to those needs is essential in choosing the most appropriate objective and spreadsheet model. This is not to say the other advantages should be ignored, just not quantified in the spreadsheet. Let’s consider each scenario more closely and give some examples.

Acquisition of new customers

In a retail purchase situation a customer may have many concerns and questions. Often a critical question in taking on a new product or service is, would the addition of your product or service actually bring new customers to the store? Keep in mind that consumers today are overloaded with product choices and a vast array of convenient purchasing options. When was the last time you went out of your way to find a particular product? Most likely this would occur when the product is a specialty good with high brand recognition. In this selling scenario, you would want to prepare a ROI spreadsheet.

Retention or retaining new customers

Does the addition of your product or service allow the buyer to have better customer satisfaction? As we have discussed in relationship selling, exceeding customers’ expectations results in keeping customers. It is much less expensive to keep existing customers than to attract new ones. How much is this actually worth to the company? It is possible to see the value of retaining particular customers through different kinds of analysis.

- • If the goal is to determine the worth of a customer you would use the lifetime value formula (see earlier discussion in this chapter).

- • If the objective is customer retention, you would choose an ROI spreadsheet using the lifetime value of the customer offset by the inventory costs of your product.

Profitability

Profit is generated by a reduction in costs or an increase in sales. Questions that are frequently addressed in this selling scenario include: Does the addition of your product or service reduce labor or operational costs? Will the purchase of the product by the reseller increase sales? The information to address these questions can be measured and dealt with in a quantitative analysis.

If the profitability objective is based primarily on reducing costs, you should choose the ROI spreadsheet. The cost savings would be compared to the cost of purchase to see if the ROI is positive. The bottom line of the ROI spreadsheet is the net savings or return to the company. If the purchase produces a positive ROI—in other words, if the savings are greater than the costs—it is a good match between the buyer’s needs and the seller’s product/service. If the purchase would produce a negative ROI—the cost is greater than the savings—it may mean the prospect is not a qualified buyer or the value proposition is not well developed (for example, there are too many product features relative to the cost targets for the customer).

If the value proposition is profitability based on increasing sales, you should choose the profit margin spreadsheet. The revenue from additional sales would be compared to the cost of purchase to project profit margin. The reseller spreadsheet is a simple calculation of costs less discounts, offset by retail price. An actual seller would supply costs and discounts. It is always important to be as accurate as possible in assigning costs and discounts; a thorough analysis of the customer’s business and your company’s own pricing flexibility is crucial to developing an accurate forecast. All research including interviews with store personnel should be documented and/or presented as evidence in your sales presentation. Let’s examine each of these spreadsheet models.

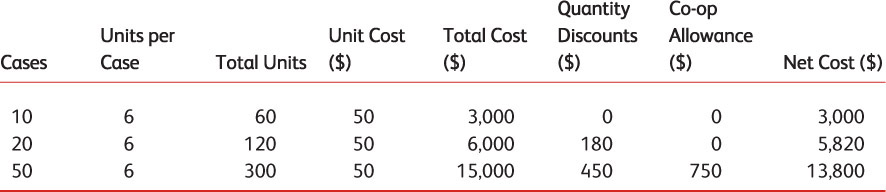

Understanding the Profit Margin Spreadsheet

- • The Units column indicates the size of the purchase in the multiples in which they are sold. For example, some products are sold only by the case and therefore units would be number of cases. If products were sold individually then it would be the number of individual units.

- • Unit cost is the wholesale price of the unit. If your unit were a case, it would be the price of the case. As stated above, this information would be readily available to you in your industry. It is not easily ascertained outside the company. You might have to find an industry average, ask for a range from an employee, or work backwards from retail price. To work backwards, you could take the retail price less the markup and discover the cost. For example, if you see a product advertised for $100 and you research the industry and discover there is usually 100 percent average industry markup, you can deduce that the cost would be $50. Another option would be to check prices at online discounters or cost clubs. They sell closer to wholesale and you could use their numbers as your wholesale cost.

- • Total cost is number of units multiplied by the unit cost. Be sure you are using concurrent numbers. For example, if you discover the wholesale cost of a bottle of water is. 29, but it is sold in cases of 12, you will first need to translate the unit cost to the cost for a case (12 ×. 29), or break down the number of units from number of cases to number of actual bottles.

Example

| Cases | Units per Case | Total Units | Unit Cost ($) | Total Cost ($) |

| 10 | 6 | 60 | 50 | 3,000 |

| 20 | 6 | 120 | 50 | 6,000 |

| 50 | 6 | 300 | 50 | 15,000 |

- • In B2B quantity discounts are often used to encourage larger purchases. The amount of the discount varies by industry and research can determine an industry standard. Quantity discounts are normally expressed as a percentage of the total cost.

- • Another common discount in B2B, especially in heavily advertised brands, is co-op allowances. This is money allocated for promotion of the seller’s product by the reseller. Co-op discounts are often a percentage of the total cost. These discounts would be offered only if the reseller engaged in advertising that would significantly promote the seller’s product. Co-op discounts are not usual for small orders or commodity items.

- • Net cost would be the result of subtracting all discounts from total cost.

Example

- • Manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) is the price of the product to the end user. It is the price without promotional allowances (markdowns, on sale, clearance, etc.). To find the best MSRP you should go to an actual brick-and-mortar retail location, not a discounter, and research the price at which your product is selling. Online resellers may discount the price and therefore you will not get an accurate MSRP. Manufacturers suggest a retail price to maintain brand equity. If you shop at a reseller location that also maintains strong brand equity you will get a more accurate MSRP.

- • Revenue is the amount of sales generated by the order. The MSRP would be multiplied by the number of units. Be especially careful that you convert units into individual units because the MSRP will be for one unit. If your total cost was figured by the case, you will need revenue projections that include all the units within the case.

Example

| MSRP ($) | Units | Revenue ($) |

| 100 | 60 | 6,000 |

| 100 | 120 | 12,000 |

| 100 | 300 | 30,000 |

- • Net profit, the bottom line, is revenue minus net cost. The buyer is most focused on this number. You should create a graph showing the increasing levels of profit with increased order size.

- • Profit margin per unit could be a persuasive indicator. The revenue from the sale of the product or service is reduced by the cost of goods sold to determine profit margin. If the profit margin generated by the unit were significantly higher than the average margin experienced by the buyer, this would be of value. For example, in a grocery store markup on staple items is generally low, often below 30 percent. If your product could generate a pm/unit of more than 50 percent, especially if shelf space needs were low, the purchase would be highly valued.

Example

| Net profit ($) | Profit Margin/Unit ($) |

| 3,000 | 50 |

| 6,180 | 52 |

| 16,200 | 54 |

- • Markup is the percentage added to the cost of the product to determine the selling price. Markup based on retail price should be included if you worked backwards to find the wholesale cost. The formula for markup is Cost / (100% – GM%)=Selling price. You can replace GM in the formula with the average markup to determine cost. Markup could be an industry average if specific numbers are unavailable. Markup is often used to determine if the return on the space your product occupies is worth the investment. For example, retail stores calculate their return on shelf space based on the sales generated from the square footage of selling space available. If your product requires more selling space than the revenue it will generate, it would be a bad purchase decision for the customer.

Understanding the ROI Spreadsheet

| Plan 1 | Plan 2 | Plan 3 | |

| Expenses | |||

| Daily | |||

| Average number of staff | |||

| Average amount of time | |||

| Labor minutes used | |||

| Labor hours | |||

| Monthly | |||

| Labor hours | |||

| Average hourly wage | |||

| Total monthly cost | |||

| Yearly | |||

| Investment | |||

| Product/service cost | |||

| Additional costs | |||

| Total yearly cost | |||

| Net savings | |||

| Over time … | |||

| ROI/month |

The ROI spreadsheet requires a deeper understanding of your buyer’s business than the profit margin spreadsheet. It also requires access to sensitive information about the company’s operations. If you are selling a product or service that will decrease costs to the customer’s business and consequently increase profitability, you need to show your buyer the value of buying/investing in your product. Profitability from the purchase is called the return on investment (ROI). In many cases the main expense is labor costs, as in the example. You can use the same format, substituting rows as needed to adapt to the other expenses.

In this example we have chosen to present three options to the buyer with each providing a greater return. It is not always necessary to have numerous options, but it does help illustrate the financial advantage of building the relationship with a long-term contract.

The purpose of the ROI spreadsheet is to persuade the buyer to invest in your product or service. The payoff of their investment, or the return, is the difference between their current expenses and the new purchase.

- • The spreadsheet begins by addressing the expenses. The buyer will be more comfortable discussing the current situation from this point of view. It is also a good idea to show the need for your product before introducing the price.

- • If your product/service is going to reduce labor costs, you first need to know the current labor costs. Begin by determining the current cost of labor associated with the task the sale will impact. If you are selling accounting software, this could be the number of people who will use the software. If you are selling Internet access, this would be the number of employees who will benefit from faster connections. In this example we have started with daily usage and built into the larger picture. Many buyers will find it easier to think in smaller time blocks. “How many minutes would you estimate you spend waiting on the phone per day?” is much easier to answer than asking the same question for minutes per year.

- • Average amount of time is the current use of time by the employees included in the staff calculation above. For example, if they use about 30 minutes a day on a task that will now be eliminated or streamlined, that would be put in the cell. Time wasted while waiting on connections or slow computers could also be included.

- • Labor minutes used are the number of staff members multiplied by the average amount of time worked. This tells us the total usage for the company on a daily basis.

- • Since most wages are calculated per hour we need to convert minutes into hours. Thus, labor hours are the labor minutes divided by 60.

Example

| Daily Expenses | Plan 1 |

| Average number of staff | 10 |

| Average amount of time | 12 |

| Labor minutes used | 120 |

| Labor hours | 2 |

- • Labor hours/month is calculated to build the bigger picture. Since investments are not made on a daily or even monthly basis, we need to build up to the yearly usage. Labor hours multiplied by 30 gives us the labor hours per month.

- • To determine the actual cost of the labor hours we need an average hourly wage. Be sure to note that this is an average. In some cases all employees impacted by the investment will be comparable in earnings, in other cases there may be great disparity between management and staff. This is your best attempt at parity and can be quite easily researched.

- • Total monthly cost is calculated by multiplying average wage by labor hours/month. This amount is the cost to the buyer of not buying your product or service.

Example

| Monthly | |||

| Labor hours | 54 | 60 | 66 |

| Average hourly wage | $9.00 | $9.00 | $9.25 |

| Total monthly cost | $486 | $540 | $611 |

Most investments in B2B are long term, not merely for 30 days. To calculate the yearly cost of not buying, we would multiply total monthly cost by the number of months in the year.

Example

| Yearly | $5,832 | $6,480 | $7,326 |

The next section of the ROI spreadsheet is the introduction of the investment or cost to buy your product/ service. These costs are usually easy to find, as they are the retail price of the good or service.

- • Product/service cost is the actual amount the business needs to “invest” in the solution. It should be expressed in the total cost for the year to keep our analysis logical.

- • Additional costs might be installation, training, maintenance, support, compatibility upgrades, etc. In building strong relationships, all costs should be discussed. Hidden costs are unethical and do not contribute to long-term relationships.

- • The total yearly costs are the sum total of the investment for that year. Services are often repeating investments. Many times a discounted price is offered for multiple year contracts. In some buying situations, a large purchase could be amortized over an extended period. All costs should appear when presenting the ROI.

Example

| Investment | |||

| Product/service cost | $5,000 | $6,000 | $5,500 |

| Additional costs | 1,200 | 0 | 0 |

| Total yearly cost | $6,200 | $6,000 | $5,500 |

The bottom line of the ROI spreadsheet is the net savings. If the purchase produces a positive ROI—in other words if the savings are greater than the costs—it is a good match between the buyer’s needs and your (the seller’s) product/service. If the purchase would produce a negative ROI—the cost greater than the savings—it may mean the prospect is not a qualified buyer or that price negotiation is needed.

As stated previously, there are often advantages to making a commitment to purchase for more than one year. It is an advantage to the seller to know they will have the repeat business, and an advantage to the buyer to know they have created a relationship with the seller that can provide them with benefits from customer service and reduced ordering costs. In the case of some B2B purchases, the one-time purchase price is spread out over the life of the product. In both these instances it is important to show the ROI over the life of the contract or product. In the example, we chose to look at the investment over a three-year period. The yearly return for each year is added together to determine the actual return over the three-year life of the investment.

Since many businesses use monthly cash-based accounting methods, it is a persuasive tool to break down the large investment dollars into monthly returns. If you take the three-year ROI and divide by the number of months in the same time period (36) you find the ROI per month. As consumers we find $99 per month easier to accept than $1,200. In B2B, the same psychology applies.

Example

| Investment | |||

| Total yearly cost | $6,200 | $6,000 | $5,500 |

| Net savings | 280 | 480 | 1,826 |

| Over time (36 months) | 840 | 1,440 | 5,478 |

| ROI/month | $23 | $40 | $152 |

If you are using the ROI spreadsheet to quantify the acquisition of new customers, a few modifications would be made. You would need to forecast the number of new customers that would be attracted. You would also need a lifetime value for the customer (see Exhibit 3.3). This would determine the revenue stream.

Example

| Minimum | Average | Exceptional | |

| Acquisition | |||

| Number of new customers | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Lifetime value | $5,000 | $5,000 | $5,000 |

| Revenues | $15,000 | $20,000 | $25,000 |

| Investment | |||

| Product/service cost | $13,000 | $17,000 | $20,000 |

| Additional costs | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,500 |

| Total yearly cost | $14,500 | $18,500 | $21,500 |

| ROI (Revenues less total yearly cost) | $500 | $1,500 | $3,500 |

The revenues generated would be offset by the cost of the product/service and any related costs. Be sure to include all costs that will be associated with the decision. In this example we are selling advertising space. The additional cost of artwork for the ad design is shown as an additional cost. If you were selling a product that would provide value through customer retention, your product cost would be the investment.

The ROI in the acquisition example shows that a $20,000 yearly investment in advertising could return $25,000 in sales revenue and thereby not only recover the expense but actually return $3,500. The spreadsheet also shows that in the worst-case scenario the return on the investment would be $500.

As you work through the spreadsheets it is important to note the challenge of these analyses is not the calculations but, rather, verifying the accuracy of the data. Without valid data the analyses are not very valuable to you as the salesperson, or the customer. Indeed, a poor analysis with invalid data could do more harm than good to the relationship. Mastering the relationship selling process means, in part, becoming comfortable with understanding, creating, and then explaining these kinds of analyses to customers.