4.

The Imitators

All we’ve done is copy Herb Kelleher’s successful

model. In fact, we’re maybe the only people to copy

it successfully and maybe take it beyond where

Southwest has gone with it. But other than that it’s

still Southwest’s model.

—Michael O’Leary, CEO, Ryanair Holdings

The nature and outcomes of imitation vary widely. Some firms copy a model as is, whereas others adapt it to their own circumstances or attempt to produce a marked improvement on the original. A few attempt to understand how a borrowed model will fit in, but others are content with replicating its most visible external feature.

Still, most firms remain focused on the barriers they can put in the way of would-be imitators of their own innovations rather than dwell on how they can benefit from imitating others. Most cannot break free from the stigma associated with imitation—to the point that many executives I have talked to took offense at the very suggestion that their firms engaged in imitation (even when it was evident that they have borrowed key ideas and features from others).

However, even those comfortable with the “i” word admitted that they lacked a systematic, proactive approach to imitation. They rarely sought lessons from their prior imitation attempts or from the experience of others in their industry and beyond. Most did not address, let alone resolve, the vital correspondence problem, which, as you have seen, lies at the heart of the imitation challenge.

Although some firms look to imitate an isolated business principle, others view an entire business system as a potential model. When the modeled system is complex, albeit structured—say, a memory chip manufacturing operation—one approach has been that of copy exact: the precise replication of a working plant in another location to the most minute detail. The assumption is that because a complete understanding of the system is virtually impossible, an exact replica will ensure the fidelity and reliability of the outcome even when cause and effect are poorly understood.

A company that replicates its own plant has unfettered access to information; and, as complex as chip manufacturing is, most of its elements (e.g., machinery, assembly room temperature) can be codified and are hence replicable. The same cannot be said of a business model used by another firm that imitators observe from the sideline, with access only to its visible elements. Imitators also find it challenging to decipher the intricate network of relations among the various elements that make up a comprehensive system. Still, as difficult as the imitation of systems and models may be, in many instances it has been accomplished successfully, whereas in other instances the imitation effort has fallen short or collapsed.

The imitation cases recounted in this chapter illustrate some of the main varieties of imitation and their outcomes, both successful and not successful, as well as the challenges involved in the process. As reviewed in detail in chapter 5, companies are especially likely to choose as their models leading firms that are large, prestigious, and seemingly successful, more often than not the industry or business segment leaders. Southwest Airlines, Wal-Mart, and Apple serve here as examples, although other examples are recounted in this chapter as well as throughout the book.

Here, I discuss how various companies have tried to imitate the model firms, the assumptions that they have made (or neglected to make), and the outcomes of the efforts. I ask whether imitators were able to observe—and, more importantly, understand—what was behind the façade of a successful model, including the relevant context associated with its apparent success, and whether imitators were able to implement the chosen variant.

Southwest Airlines

Southwest Airlines started in 1971 when it launched a service between its Dallas, Texas, base, Houston, and San Antonio with three Boeing 737 aircraft. The first commercially successful discounter, Southwest led a dramatic change in the airline industry, when discount carriers, formerly a marginal portion of the U.S. domestic market, came to control one-third of the market. Southwest’s business model seemed simple enough.

- Fly short-haul and point to point (rather than connect via a hub), simplifying route structure and eliminating the time and complexity of luggage transfer.

- Use the same aircraft type (Southwest even standardizes cockpit instrumentation on its various 737 models), triggering savings in equipment purchase, maintenance, staffing, and crew training while enhancing deployment flexibility.

- Keep planes in the air longer, a key advantage in a capital-intensive industry, by rapidly turning them around (especially important for short routes) and maintaining flexible work rules.

- Land in secondary or less congested airports (permitting still faster turnarounds). These airports are less likely to be contested or dominated by established carriers and charge lower landing fees, but they are close enough to major destinations that passengers find them desirable.

Moreover, crews are paid in the lower range, and this practice, combined with higher productivity, makes for the lowest cost per block hour among the major industry players.1 The Southwest model has proved to bring costs down by as much as 40 to 50 percent compared with the models of legacy carriers and, together with high load factors, supported a 60 percent fare drop and a tripling or quadrupling of traffic on many routes. The same principles of simplicity are applied to sales (most are made online, saving on costs and commissions and improving cash flow), distribution, and service. Customers get low, simplified fares (compared with the convoluted systems of legacy carriers), no advanced seating (now offered at a premium), and no-frills and yet energetic service by crews willing to go the extra mile.

Although Southwest set as its competition Greyhound buses rather than established carriers, its head-to-head airline competitors invariably found themselves on the losing side. By 2008, the airline was flying 104 million passengers per year in eighty-two markets. In sharp contrast to the industry as a whole, Southwest has been consistently profitable and has come to command a market value greater than that of all the major legacy competitors combined.

Although recent performance benefited from fuel hedging, this profitability can be explained by Southwest’s financial strength as well as its cost-cutting culture. By now a large carrier, Southwest has kept to basics such as short routes (average trip length grew modestly, from 525 miles in 1995 to 818 in 2006) and quality service (in 2008, it had the lowest complaint rate of any carrier). To accommodate its growing fleet, Southwest introduced automated production control, a practice that reduced scheduled maintenance by 10 to 15 percent and increased aircraft utilization rates. Maintenance planning and aircraft routing were synchronized, lowering plane downtime.

Still, as much as it was the first to introduce its innovative business model, Southwest Airlines was also an avid and successful imitator. Its model was based in part on crucial lessons drawn from prior failures of discount carriers such as People’s Express; the careful selection of imitated elements, such as the IT infrastructure replicated from legacy carriers, was directly based on those prior lessons. Donald C. Burr, head of People’s Express, attributed the demise of his airline, the first large-scale discounter, to information technology deficiencies. Southwest management understood well that this deficiency was equally relevant, if not more relevant, to an upstart bent on cutting costs through operational efficiencies while maintaining quality, and the airline sought to remedy it while improving on the models from which it was taken. Southwest, in other words, took it upon itself to resolve the correspondence problem in the way imovators do—that is, not only by matching the correspondence requirements but also by exceeding them in a way that creates distinct value.

Southwest’s success took the industry players by surprise. The point-to-point model was counterintuitive, because the hub-and-spoke system was considered superior in cost, coordination, and pricing power.2 These perceived advantages and the prior failures of discount airlines such as People’s Express and Air Florida allowed the new airline to fly under the radar of its competitors, avoiding serious attention for years.

When Southwest finally gained visibility, competitors saw a deceptively simple model, supposedly amenable to easy replication. Flying the same aircraft type was a no-brainer. Removing frills promised to lower costs and simplify operations. Flying point to point and into secondary airports was also easy: even though it meant lower utilization of hubs for hub-and-spoke carriers, this drawback was mitigated by incentives offered by local communities eager to attract air service.

Imitating Southwest

One wave of imitators—represented by ValuJet (now called AirTran) and Spirit—sought to replicate the Southwest model of point-to-point, single-model flying but take it one step further by removing any remaining frills from the original no-frills model. As a Kidder Peabody analyst commented, “Many startups have aspired to the noble claim of being the next Southwest. But only ValuJet has the costs, margins, and management experience to even approach that title. We call it Southwest without the frills.”3

Similarly, Spirit Airlines has become the “king of cheap,” transforming itself from a conventional low-cost airline to an ultra-low-cost carrier that offers some seats for a penny but charges for any conceivable service on the ground and in the air, even a glass of water. In biological terms, ValuJet and Spirit engaged in emulation (the copying of observable actions), which falls short of full-fledged imitation in that emulation fails to capture opaque elements. This was possible because both imitators followed visible and codified elements in the tradition of the copy exact model.

Former Skybus chairman Bill Diffenderffer suggests that this type of replication tends to focus on a single aspect of the model—in this case, low cost.4 Such single-aspect repetition amounts to what biologists call imprinting, the instinctive replication of an action. Imprinting works when the model is in plain view and actions are visibly related to the imitation target, but it is rarely useful in complex or opaque situations. In a well-known biological application of imprinting, a duckling follows not only its mother but also any moving object: the action might be similar, but the outcome varies markedly, with possibly ominous consequences in the latter case.

Similarly, the business limits of lesser forms of imitation are obvious. Consider the case of Diffenderffer’s airline, Skybus, which recruited veterans of Southwest and Ryanair, a successful European imitator, to help absorb the model. Flying single-model aircraft, Skybus offered discount service to secondary airports in large city destinations, with the first ten seats on every flight sold at $10 each; like Ryanair, Skybus supplemented its revenue by using its airplanes as billboards. All this proved to no avail, and in April 2007 Skybus ceased operations.

Although the official announcement cited fuel prices and a deteriorating economy, Diffenderffer also blames the airline’s backers, who were glued to an impossible combination: a premium service à la JetBlue at Ryanair prices (more on those carriers later). As is usually the case in imprinting and emulation-like imitation, deviations from the model were discouraged. For example, Skybus avoided using a reservation system that could bring in more customers because it was not a part of the model. Portions of the Skybus model—such as charges for checked luggage, priority seating, and the selling of the first few seats at a sharp discount—were in turn imitated by other airlines after Skybus’s demise. The $10 seat idea was also adopted by BoltBus, a joint venture between Greyhound Lines and Peter Pan Bus Lines, which offers at least one seat for a dollar.

Differentiating from Southwest

Another group of Southwest imitators, represented by JetBlue, sought to retain core features of the model but differentiate on a strategically important element. JetBlue’s founder, David Neeleman, worked at Southwest after it acquired his Morris Air start-up and used to complain that Southwest was reluctant to tweak its formula. Neeleman chose service as a differentiator, producing what might be called “premium discount” service. If most discounters offer safety and punctuality with no-frills service, JetBlue offers semipremium service, with assigned leather seats and personal TV screens. JetBlue, which emphasizes service-related performance and traditionally has one of the lowest ratio of bumped passengers, recruited Southwest veterans, including a CFO and a head of human resources. Still, JetBlue retained the Southwest model of a point-to-point, single-aircraft fleet (it later added a regional jet) and simplified its fare structure.

These actions permitted JetBlue to control costs as well as Southwest did (for instance, in 2006, its cost per available seat mile, or CASM, was 8.27 cents versus 9.79 cents for Southwest) while drawing passengers who sought better amenities. Another reason for JetBlue’s success was that it rapidly expanded into regions having little Southwest presence and that it established a hub in New York’s JFK Airport that enables international connections without incurring any of the costs associated with seamless intercarrier routing.

“Carrier Within a Carrier” Imitators

Some imitators seek to preserve their long-running business model while absorbing an imitation into a separate unit cordoned off from their main operations. The idea is to extract the benefits of the imitated model while preserving sunk investment and infrastructure, to reach new markets and customers while retaining existing ones, and to navigate around labor agreements and a corporate culture that is resistant to change. The concept is enticing in that it offers the promise of having your cake and eating it, too, and it seems to circumvent the need to address the correspondence problem.

However, as you will see, the benefits are illusionary. The correspondence problem cannot be avoided but is simply shifted and in many ways amplified, because the imitator now must deal with two competing systems that cannot be reconciled but at the same time are not fully compartmentalized. The likely outcome is a halfhearted imitation that produces the worst, rather than the best, of all worlds.

The airline industry illustrates this principle. As Southwest commanded an ever-increasing market share, legacy carriers became keen to prevent their customers from defecting as well as to tap price-sensitive new customers. Shackled by union agreements and determined to protect their investment in hub-and-spoke infrastructure, legacy carriers came up with a tempting concept: a carrier within a carrier. The idea was to preserve the existing model, with its hub route system, frequent flier programs, and first-class section, and establish a separate unit that would essentially replicate Southwest Airlines and compete with discounters on their own terms.

Among the spin-offs were Continental Airlines’ CALite, Shuttle by United (to be followed by Ted in 2004), US Airways’ MetroJet, and Delta’s Song. These carriers within a carrier copied Southwest’s simplified fare structure, eliminated perks such as onboard food, improved aircraft and crew utilization, and reduced selling and distribution costs. Some, though not all, have also adopted the single-aircraft formula. Others went as far as to mimic Southwest’s casual dress and informal attitude by flight attendants. Late legacy imitators, such as Delta’s Song, sought to borrow not only from Southwest but also from successful differentiators such as JetBlue.

CALite, Continental Airlines’ low-cost unit, was established in 1993 following the exit of its parent from a second bankruptcy filing. The unit was supposed to compete with Southwest (though initially shying away from its rival’s geographic base in the Southwestern United States), copying principles such as point-to-point flying, no-frills service (single-class, no meals), fast turnaround, and a casual-mannered flight crew. Unlike Southwest, CALite offered assigned seating and frequent flier miles (at a reduced level) and, in a departure from the Southwest model, used multiple airplane types.

The imitation proved a dismal failure. In its 1994 10-K filing, Continental noted that its CALite unit, operating what were known as “peanuts flights,” encountered “operational problems” and was unprofitable. It added that “linear” point-to-point flying was responsible for 70 percent of the unit’s losses, because it prevented the airline from leveraging its Houston and Newark hubs. In the meantime, the managerial time and capital expended in launching and operating CALite eroded service at the main carrier, and customer complaints mounted. In 1995, the unit was folded into its parent, with only portions of the model, such as quick turnaround time, surviving. Continental’s CEO, Gordon Bethune, later commented that “if we had let things go another six months, we could have lost the farm.”5 Bill Diffenderffer, at the time a senior vice president at Continental, says that CALite failed because it cannibalized the full-fare passengers of the main carrier, created brand confusion, and, instead of generating real cost savings, simply shifted costs around.6

Other legacy spin-offs fared no better. Launched in 1994, United’s Shuttle took direct aim at Southwest’s territory. Like the original, it offered frequent point-to-point service but retained a first-class cabin (a feature that was popular with business travelers, who could use their status or miles to upgrade), advanced seat assignment, and frequent flier miles. This initiative collapsed when Southwest, by then a strong carrier, mounted an aggressive response. United failed to create a cost structure for the division that would be commensurate with running a low-fare airline; for example, it maintained supervisory staff levels at an identical level to those of the main carrier.7

Undeterred by the failure, United launched another spin-off, Ted, in 2004, this time avoiding head-to-head competition with Southwest and instead targeting weaker Frontier and America West. Ted differentiated itself from Southwest by offering amenities such as satellite radio and free movies, but passengers were not enticed and the unit was shut down in June 2008, with one magazine proclaiming, “Ted is dead.”8

A similar attempt was US Airways’ MetroJet unit. With a bloated cost structure, it could not handle the downturn of 9/11 in 2001 and closed in December that year. “MetroJet,” reflected Southwest chairman Herb Kelleher, “said they were going to be a low-fare airline, but they weren’t a low cost airline.”9 Years later, Naresh Goyal, founder of India’s Jet Airlines, echoed the theme, saying, “There are no low cost airlines in India, only low-fare, no-profit carriers.”10

Yet another try came from Delta, which botched a carrier-within-a-carrier spin-off dubbed Delta Express in the 1990s and launched Song in 2003. With a $75 million war chest, a team made up of executives from Delta and consulting firm McKinsey was assigned to deflect the encroachment of discounters even at the cost of short-term profitability. Having studied the failure of Delta Express and other carriers within carriers, the team set a goal of fifty minutes’ turnaround time, with planes kept in the air for more than thirteen hours a day, roughly 20 percent better than in Delta’s main operations. Flight attendants were expected to tidy up cabins before landing, and cleaning crews entered planes as passengers were exiting at the other end. Unit management hoped to wring out close to one-quarter of operational expenses via lower crew wages and more efficient aircraft usage.

One lesson from past spin-offs was to obtain more independence from the parent company, but Song and Delta shared pilots, maintenance, and other resources. A second lesson was to create a distinctive brand, but the Song brand differentiated in pretty much the same way as an earlier follower, JetBlue. When asked what separated Song from JetBlue, Tim Mapes, Song’s chief marketing officer, evoked images of emotional attachment and lifestyle: “We are going to build a brand, not just an airline.” 11 Song peddled its own branded, upscale merchandise on board as well as in Song-branded retail stores in New York’s SoHo and in Boston, and the company further differentiated itself by focusing on female customers and by maintaining visible ties with its parent.

Unfortunately, these were not differentiating factors that customers were looking for or were willing to pay for, and, given the presence of JetBlue, Song could not even offer novelty. At the same time, these factors added to costs: constrained by prior labor agreements, Song was paying its pilots on the same wage scale as in the parent carrier, with its industry leading wages. Flight attendants and most ground crews worked for lower wages and at lower staffing levels (e.g., four flight attendants instead of the six assigned to a 757 in the main carrier), but this staffing level hurt morale, undermining the promise of superior service. Song operated mostly single-type aircraft, but to turn a profit its 757s needed more passengers than Southwest’s 737s and JetBlue’s Airbuses and took longer to turn around. In two years, Song was gone. A similar fate awaited European spin-offs (e.g., KLM’s Buzz) that remained integrated with the main carrier.

All in all, not a single legacy carrier succeeded in imitating Southwest Airlines by adopting a carrier-within-a-carrier formula, with the possible exception of Silk Air, a Singapore Airlines wholly owned subsidiary. Silk Air leveraged its parent’s superb hub, Changi airport, as a base for point-to-point flight connections to long-range international destinations. For the other airlines, the spin-off model yielded cost savings that were too modest to close an operating cost gap of almost 50 percent. Legacy carriers also had to carry the significant administrative burden and costs associated with the heavily regulated International Air Transport Association structure, from which their spin-off units could not be shielded. Encumbered by an existing customized fleet, spin-offs could not match even codified elements of the Southwest model, such as standard versions of aircraft ordered at the bottom of the industry cycle.12

Would-be imitators were even further behind in imitating tacit elements, as Kelleher wrote in the firm’s 2005 Annual Report: “While a number of other airlines may attempt to imitate Southwest, none of them can duplicate the spirit, unity, ‘can do’ attitude, and marvelous esprit de corps of the Southwest employees, who continually provide superb Customer Service to each other and to the traveling public . . . Even though many have attempted to imitate many aspects of Southwest, they cannot duplicate our most important element of success—our people.”

Although Kelleher talked about good employee relationships and esprit de corps, the Southwest culture is also one of a constant quest for cost savings, something legacy carriers were not immersed in; this is a challenge that parallels that of pharmaceutical innovators seeking to enter generics. The result was an imitation that lacked the fundamental ingredients that made the original a success and at the same time clashed with the imitators’ own systems, producing the worst, and not the best, of all worlds. In the meantime, legacy carriers were so fixated on their imitation target that they took their eyes off the ball and neglected to look at the possibilities of improving their existing models. Diffenderffer observes that network carriers have forgotten that the legacy model worked well for airlines like Cathay Pacific, Singapore Airlines, and British Airways and have forgone ways to differentiate and make a profit in the network world.13

A similar trend was observed outside the airline sector. To compete with cut-price clones, IBM established its low-end Ambra division in 1992, outsourcing production and selling by mail and phone. The idea was to copy the clones—the same clones that were virtually invited in when IBM released its “Purple Book” of product code to encourage use of its standards but were now eating its lunch. The unit shut down in 1994 after encountering many of the same problems that plagued airline spin-offs, such as brand confusion. This division stood in sharp contrast to the structure IBM used when launching the PC, which was a separate profit center located far from headquarters and with autonomy to source from anywhere, to set prices, and to establish sales channels.

Similarly, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) stumbled when it tried to enter the PC business from its main operation without establishing the necessary low-cost structure. In the automotive sector, General Motors created its Saturn division as an imitation of Japanese car manufacturers, adopting practices such as reducing the number of job classifications and replacing conventional assembly with teams. This attempt, too, has failed, as did Extreme, the discount division of supermarket chain Albertsons. In all those instances, the attempt to replicate a model developed elsewhere, while failing to sever relations with an existing model rooted in another context, has proven unworkable.

Importing the Southwest Model

An important form of imitation involves the importation of a model from one environment to another, usually across borders. WestJet, in which JetBlue founder David Neeleman has been an investor, was launched in 1996 and copied Southwest’s formula in the Canadian market. “We decided to replicate the Southwest model and Canadian-ize it,” says Clive Beddoe, the airline’s chairman and CEO.14 Like Southwest, WestJet uses only 737s but provides assigned seating, food (for purchase), lounge access, and JetBlue’s television service. The formula has been highly profitable. In 2005, Spring Airlines, Eagle Airlines, and Okay Airlines emerged in China with the same idea, and Neeleman took the model to Brazil with Azul, a JetBlue look-alike airline that tries to match some bus fares.

However, the best exemplars of successful importation of the Southwest model are two European airlines: Ryanair and EasyJet. Although all imitators are subject to the correspondence problem, importers face a wider array of challenges because they transplant a model in another soil and must consider differences between the two environments. In the case of these two European start-ups, certain similarities supported imitation: just as the deregulation of the U.S. aviation market was vital for the emergence of Southwest, the deregulation of the European market in 1993 opened up opportunities for importers from that continent.

Although intra-European travel is mostly international and hence potentially more complex, the removal of passport and visa restrictions as part of European Union integration made for smoother travel and created additional demand. Other conditions conducive to a Southwest-type model also prevailed: secondary airports were plentiful, most flights were short, and the United Kingdom offered a cheap, lightly regulated base akin to Dallas. Higher population density was an advantage beyond what was available in the United States. The EU market presented tougher competition because of the wide availability of rail service, but airlines could compensate for this with even greater attention to cost containment. Finally, Southwest’s failure to expand to Europe removed a potentially formidable competitor.

Ryanair started life in Dublin in 1985 as a discount carrier undercutting the pricing of the British and Irish flag carriers. There was one problem: the new airline did not have the cost structure to support its low fares, and that shortfall led to £18 million worth of losses. As the story goes, when Ryanair’s founder, Tony Ryan, recruited Michael O’Leary, now CEO of Ryanair Holdings, as his personal assistant, O’Leary promptly advised his boss to shut down the money-losing enterprise. Instead, in 1991, Ryan took O’Leary to Dallas to visit Southwest Airlines and meet with its CEO and president. When the two returned home, they set out to replicate the Southwest model. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, O’Leary said (as noted at the beginning of this chapter), “All we’ve done is copy Herb Kelleher’s successful model. In fact, we’re maybe the only people to copy it successfully and maybe take it beyond where Southwest has gone with it. But other than that it’s still Southwest’s model.”15

Rather than imitate subtle portions of the Southwest model, such as its friendly service, Ryanair went with a vengeance after the codified elements. It retained the basic tenets of the original model but went further in pursuit of the formula of selling at the lowest possible price to the greatest number of people. It relentlessly reduced overhead and charged for any conceivable service, from baggage handling to priority boarding, assigned seating, and drinks. Seats do not recline, allowing more passengers to fit in. Window shades and front seat pockets are nowhere to be found, because they add weight and require cleaning, adding to turnaround time.

More recent steps include the elimination of check-in stations and checked luggage, and the company is considering the option of charging passengers to use the toilet on board (mostly to shorten turnaround time) and to offer a cheaper fare for those willing to stand during the flight. Every inch inside and outside the aircraft is exploited for advertising, and tie-ins with related providers (such as rental cars) add revenue. Flight crews buy their own uniforms, and office workers purchase their own pens; virtually all tickets are sold online. A frequent flier program does not exist.

“We’re like Wal-Mart in the US—we pile it high and sell it cheap,” says O’Leary.16 This theme was echoed by an analyst who called the airline “Wal-Mart with wings.”17 The formula has been highly profitable, with net margins hovering around 20 percent, some three times that of competitors. Southwest’s Kelleher complimented Ryanair by calling it “the best imitation of Southwest that I have seen.”18

For its part, EasyJet mates the Southwest model of low cost with the superior service and convenience of flying into major airports à la JetBlue. It boasts, like Southwest, that “people are a key point of difference” and “are integral to our success.” On its Web site, the company acknowledges “borrowing the business model from American air carrier Southwest” but adds that “our customer proposition is defined by ‘low cost with care and convenience.’ This means that while we are committed to keeping our costs low, we will provide our customers with a quality product and good service.”19

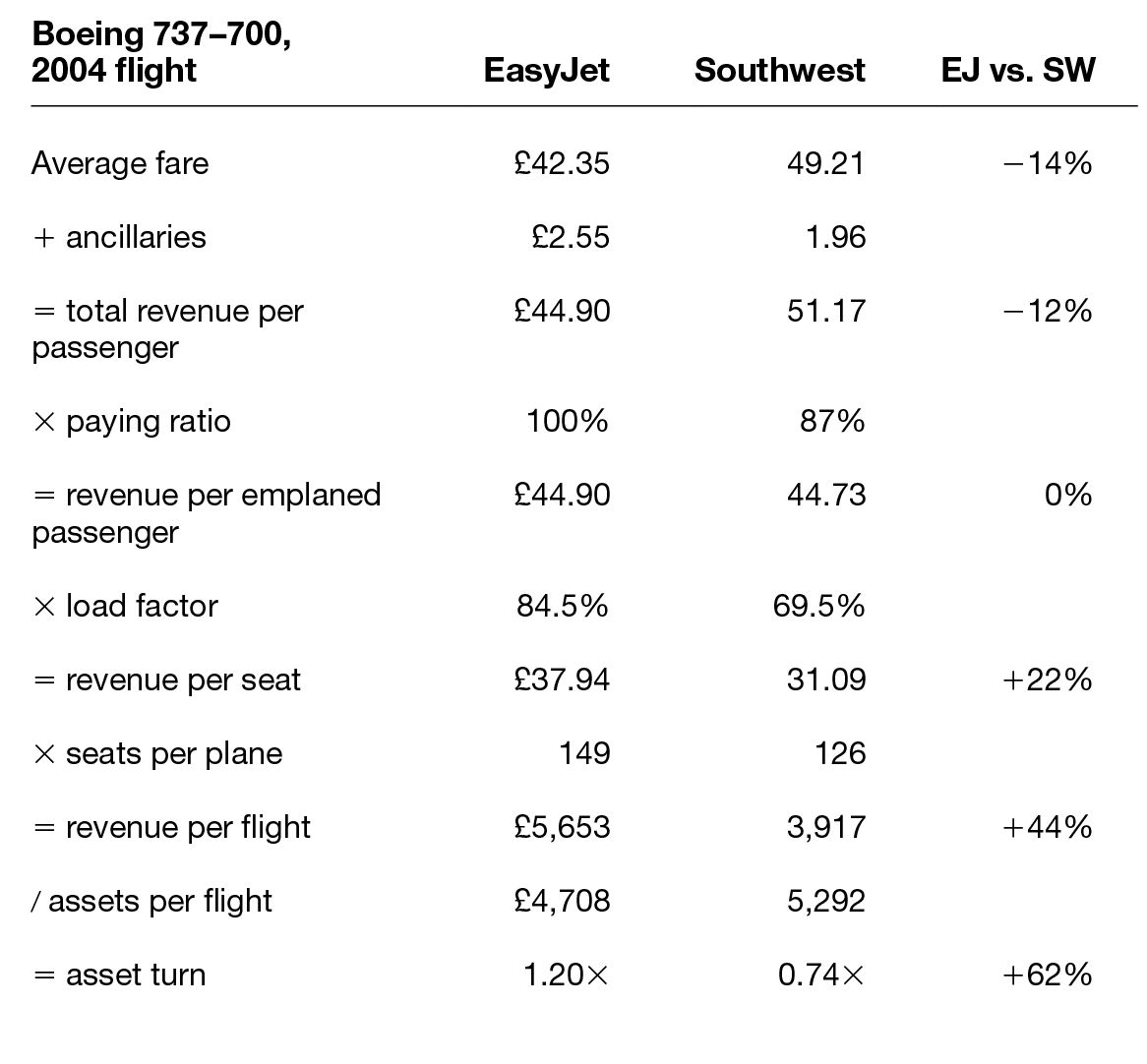

At a 2005 conference, EasyJet management acknowledged copying from Southwest the ideas of point-to-point service, a single-craft (same model) fleet, a balance of small and large airports, quick turnaround, and a high utilization schedule; however, it claimed to surpass Southwest in seat density and load factor (84.5 percent versus 69.5 percent). At the same time, it claims to have pioneered direct sales (the company does not pay travel agent commissions and does not participate in global distribution systems), boasts nearly 100 percent Web-based ticketless sales with no restrictions, uniform one-way pricing on all flights (compared with Southwest’s six fare categories, down from eleven in 2000), with prices increasing (rather than declining) closer to departure. EasyJet took the simplicity concept further into everything it does, including crewing (it has no seniority scales). See table 4-1 for a summary of how EasyJet balances imitation and innovation.

EasyJet not only enjoys a considerable cost advantage over established competitors such as British Airways and conventional discounters such as British Midland, but also its results compare favorably with Southwest’s (see table 4-2).

Like Southwest, EasyJet says that “many have tried to imitate EasyJet’s business model, but few have succeeded” but contends that many of its own innovations have been copied, including its uniforms and its one-way pricing, which was adopted by Ryanair (which in 2000 had six fare categories) and by British Airways, which made such pricing optional.20

Once Ryanair and EasyJet proved successful, Asian importers followed. Unlike the United States and Europe, Asia is not politically and economically integrated, and, because international flights are governed by bilateral agreements, routing is more complex. Although this circumstance calls correspondence into question, sufficient compensating factors exist. For instance, Asian customers are very price sensitive, and that makes discount fares more enticing; and even though cheap substitutes (bus, rail, and ferries) abound, they are notorious for old equipment, questionable safety, and rudimentary conditions, making even no-frills air travel look attractive.

TABLE 4-1 Imitation and innovation in the EasyJet business model

| Element of business model | Pioneer |

|---|---|

| High asset turn with low fares | |

| Point-to-point network, no hubs | Southwest |

| Simple fleet | Southwest |

| Balance of small and large, convenient airports | Southwest |

| Quick turnaround, high utilization schedule | Southwest |

| High seat density | Beyond Southwest |

| High load factor | EasyJet |

| Simple pricing model | |

| One-way pricing on all flights | EasyJet |

| No restrictions (Saturday nights, etc.) | EasyJet |

| One price on each flight at any one time | EasyJet |

| Price goes up, not down, closer to departure | EasyJet |

| Transparent, consumer-friendly, easy | EasyJet |

| Low-cost distribution model, from start-up | |

| 100% ticketless | EasyJet |

| 100% direct to the consumer | EasyJet |

| Zero travel agents’ commission | EasyJet |

| Zero use of global distribution systems | EasyJet |

| Initial sales through call center, phone number on side of plane | EasyJet |

| Nearly 100% Web distribution | EasyJet |

Source: EasyJet. 2005. Presentation at the UBS 2005 Transport Conference, London, September 19–20. Used with permission.

Comparative performances for EasyJet and Southwest

Source: EasyJet. UBS 2005 Transport Conference, London, September 19–20. Used with permission.

Air Asia’s Tony Fernandes based his airline on the Ryanair model, enticing Conor McCarthy, former COO of Ryanair, to sign up for a 5 percent stake. Air Asia operates one aircraft type, although it switched from the Boeing 737 to the Airbus A-320, which it claims is 12 percent cheaper on a unit cost basis and 20 percent cheaper on a cash cost basis. Like Southwest, Air Asia had bought the Airbus planes at the depth of the industry downturn after the outbreak of SARS and the attacks of 9/11. Food and drinks are not allowed on board Air Asia flights, presumably so as not to offend religious sensitivities but also to reduce turnaround time. Bank account transfer has been introduced as a substitute for credit cards, which are not yet common in that part of the world. 21

Recently, Fernandes has launched the long-haul Air-AsiaX, which offers premium seating, but he insists he is “sticking zealously to the bible of low cost competition” by avoiding interline connections and by striving to keep his planes in the air 18.5 hours a day, higher than any other airline. 22 Once Asian imitators got going, they spread quickly, with dozens of discount airlines offering versions of the Southwest model or second-generation imitations such as the EasyJet/JetBlue model of frilled discount adopted by Adam Air. In India, Air Deccan copied the Southwest model in 2003 but was soon followed by hordes of copycats unable to make money in the crowded skies. 23

Finally, some airlines adopted selected elements of the Southwest model. This process looks simple enough, because it does not involve an entire system and enables selectivity, but at the same time there is a risk that the imitator will fail to duplicate the intricate relationships among the model’s various elements and will be left with a feature that does not fit with other system elements or lacks critical support components in the original model.

To preempt a Southwest assault on its Seattle hub, for example, Alaska Airlines chose to deploy a single aircraft type, accelerate turnaround time, and reduce the cost of customer interface à la Southwest. At the same time, it retained premium differentiation by providing a first-class cabin and a frequent flyer program, but its formula of delivering “the best value in the industry” has shown mixed results.

America West has had some success by transforming itself into a discount variant—with a CASM of 7.81 cents, very close to Southwest’s 7.77 cents (in 2004)—while maintaining a hub and a first-class cabin. It emphasizes operations and service, catapulting from worst to first in on-time performance between 2007 and 2008.24 To reinforce its differentiation from no-frills discounters, the airline (renamed US Airways) imitated Continental Airlines practices such as cash rewards to all employees when operational goals are met and individual awards for service. Other imitators have had some success by copying isolated elements of the Southwest model, such as productivity pay, which provided an incentive for pilots to turn planes around fast.

Wal-Mart

The year 1962 was a momentous year in discount retailing. Kmart (reincarnated from an 1899 five and dime store chain, itself modeled after Woolworth), Wal-Mart, and Target were all founded that year, as was Woolco, Woolworth’s discount division. None of these was the discount store pioneer, having been preceded by E.J. Korvette, Mammoth Mart, Zayre, and Vornado, among others.

By 1962, discount retail was already a $2 billion industry. The pioneers are now gone, and, with the exception of Woolco, the 1962 entrants lead the category and the retail sector as a whole.

The most renowned among them is Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, with more than $350 billion in annual revenue. Famous for its large scale and “everyday low prices” (“stack them high and sell them low”), Wal-Mart is well known for superefficient logistics and information systems. It was the first retailer to automate supply chain management, beginning with computerized inventory control in 1974 and proceeding to point-of-sale automation in 1979, electronic data interchange in 1981, and a satellite network in 1985. Its vendor-managed inventory system links suppliers with distribution centers and retail outlets, where sales are continuously tallied and analyzed. A cross-docking system served by a proprietary truck fleet and distribution centers minimizes inventory and lowers sales cost by 2 to 3 percent compared with the industry average.

The efficiencies yield major savings: when it won the Retailer of the Year award in 1989, Wal-Mart’s distribution costs were estimated at 1.7 percent of sales, versus 3.5 percent for the then bigger, scale-advantaged Kmart, and 5 percent for Sears. Wal-Mart’s logistics and information systems also enable close monitoring of customer trends, enabling the retailer to adjust purchasing and merchandising.25

Wal-Mart’s strategy was imitated not only by its retail competitors but also beyond the sector. O’Leary, Ryanair’s boss, was proud for the airline to be called “The Wal-Mart of the Sky,” and when Dell CEO Kevin Rollins was asked about his company being labeled “the Wal-Mart of computers,” he retorted, “They’re trying to damn us with faint praise. [But] we think of it as high praise, when you look at Wal-Mart’s success.”26

Selected elements of the Wal-Mart model, from its vaunted information system and supplier tie-ins to its door greeters, have been avidly copied by many in the industry and beyond. Yet as much as Wal-Mart has become a model for others, it has shown a keen ability to look at and, where appropriate, imitate other firms and business forms. Wal-Mart’s founder, Sam Walton, was quoted as saying, “Most everything I’ve done I’ve copied from somebody else”; for example, the company’s hypermarkets were opened after Walton saw the format on a visit to Brazil.27

Wal-Mart was also quick to adopt competitors’ non-proprietary, third-party innovations, such as Target’s computerized scheduling system. In 2000, Wal-Mart successfully defended an infringement suit before the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that dress design was not protected by law. When U.S. newcomer Tesco opened small outlets offering fresh produce, Wal-Mart quickly followed the innovation of its one-time imitator with its Market Side version.

Wal-Mart, however, was not only an imitator but also an imovator: when it borrowed, it also sought to perfect, improve, and leverage key strategic junctions. An example is bar code technology, which Wal-Mart adopted from the grocery industry. Instead of using it only to tally prices, as in the original usage, Wal-Mart leveraged the technology to analyze purchasing patterns—a valuable capability for any retailer but especially for one that competes on supply chain efficiencies and pricing.

Imitation by Kmart and Other Discounters

Contrast Wal-Mart’s strategy with that of rival Kmart. Backed by the capital, know-how, and experience of five and dime stores, Kmart enjoyed a head start in the discount segment. At the end of 1963, it owned 53 stores, whereas Wal-Mart was contemplating opening its second; by 1979, Kmart had 1,891 stores versus 229 for Wal-Mart. The scale advantage translated into savings in purchasing, marketing, and distribution, but it did not offset Wal-Mart’s operational efficiencies. Kmart failed to invest in support systems and outsourced its transportation and management information systems, because keeping them in house could not be justified by traditional ROI criteria. As a result, while Wal-Mart spent less than 2 cents on distribution per dollar of goods sold (the industry’s lowest), Kmart spent 5 cents.

It was only in early 1982, after it had fallen far behind, that Kmart began to imitate Wal-Mart in earnest. It started with information technology, putting a former Wal-Mart consultant in charge of the effort. Unfortunately, Kmart lacked the capabilities and circumstances to make the most of the effort. Many of its stores were placed in less attractive urban areas so as to reach its target customers, but this location kept out-of-town shoppers away and made it difficult for trucks to deliver efficiently. Kmart recognized the problem in 2003, when it pulled out of the fresh food business, where distribution is critical. It then tried to copy selected Wal-Mart elements, such as installing bag carousels and negotiating prices based on shelf space rather than volume alone. With a higher cost structure, Kmart failed to match Wal-Mart’s price advantage, and so Kmart tried to shift up-market. But it lacked the knowledge and brand name to cater to this segment, and its store locations did not help. Merged with Sears, a reorganized Kmart continues to struggle. 28

Dollar General has taken a route somewhat akin to that pursued by Ryanair. The company was established in 1939 but in later years has become a keen observer of Wal-Mart, to which it consistently refers in its annual reports. Dollar seeks to outsave and outsimplify the Wal-Mart model. It maintains low inventories, limits advertising costs, and locates in low-rent areas. It keeps a lid on costs by limiting its offerings to a narrow range of small-ticket items and differentiating itself with the convenience of a smaller, quick-in-quick-out urban outlet. Together with a sophisticated supply chain, the limited number of sale items allows Dollar to put operating costs on par if not lower than Wal-Mart’s. For instance, in 2003, when Wal-Mart earned 3.5 cents per dollar in sales, Dollar made 4.3 cents. Wal-Mart reacted to Dollar General by testing a “Pennies-n-Cents” section in some of its stores that offers a similar product selection at identical prices.29

Best Buy’s chairman, Dick Schulze, announced in 1995 that ten years from that time Best Buy would be a $100 billion firm, a prediction echoing that of Wal-Mart’s founder in 1990. Now Best Buy is the largest U.S. electronics retailer and is expanding internationally. Taking a page from Wal-Mart, Best Buy seeks operation and scale efficiencies, but it differentiates itself by offering customers much greater product variety, technically literate assistance, and ease of shopping, winning awards for best signs and aids to shopping, best layout for helping customers find what they are looking for, fastest checkout, and most helpful advertising. When Schulze made his prediction, Best Buy was the only major retailer to come close to Wal-Mart’s cost of doing business, which it had done by imitating Wal-Mart’s supply chain and focusing on increasing transaction rates rather than measuring performance strictly in terms of profit per transaction.30

Combined with Wal-Mart’s foray into big electronics, Best Buy’s strategy put Circuit City in a bind. Like Skybus, Circuit City tried to imitate the two incompatible models: one focused on price competition, the other on knowledge, experience, and service. Desperate to cut costs but lacking in operational capabilities, Circuit City took the extreme measure of firing its best (and hence highest-paid) salespeople, in essence removing the in-store professional service differentiation with Wal-Mart. At the same time, Circuit City established its Firedog installation service, a copy of Best Buy’s Geek Squad, which presumably was intended to provide differentiation from Wal-Mart at what P&G would call “the second moment of truth”: the point of usage. In so doing, Circuit City created an incompatible model that provided neither the best price nor the best customer service. By the end of 2008, Circuit City was in liquidation.

Learning to Imitate

Toys ‘R Us faced a similar onslaught to that experienced by Circuit City when Wal-Mart started expanding aggressively into toys. It initially repeated the error of legacy airline spin-offs, imitating a low-price model without the low-cost basis to match. Only after being acquired by a group of investors in 2005 did the company shift away from price competition, change store layout, improve merchandise turnover, and invest in training. Toys ‘R Us also started to work closely with manufacturers to generate unique product ideas, the same strategy pursued by Target. Toys ‘R Us imitates Wal-Mart practices in discount pricing and supply chain but has now managed to differentiate itself sufficiently to draw a modest price premium, compensating for its scale and efficiency disadvantages. The company has also become more agile in taking advantage of emerging and differentiating opportunities, most recently by opening small stores and stands in malls vacated by bankrupt Kay Bee Toys.

Supermarket chains went through a similar learning curve. After trying to match a Wal-Mart-like pricing structure that their operational cost models could not sustain, they shifted to compete on ambiance, fresh selection, and unique products.

Kroger, for example, maintains the cheapest price position among traditional grocers, and its urban stores offer selected groceries at very low prices; it differentiates itself by offering a more upscale shopping experience, greater selection, smaller packaging, and the convenience of prepared food. This practice allowed Kroger to take market share from smaller grocers while holding its own vis-à-vis Wal-Mart and other large retailers. Kroger also contracted with Dunnhumby, a Tesco-owned research firm, to analyze shoppers’ purchase patterns.

The Home Depot, Staples, Nordstrom, and Gap also copied selected Wal-Mart features, such as bar codes, supplier information sharing, and point-of-sale automation, practices that enabled them to narrow the cost gap without giving up differentiating factors.31

Another successful differentiating imitator is Target. Like JetBlue and Best Buy, Target differentiates itself from Wal-Mart by positioning as “premium discount,” providing higher quality as compared with discounters and at a lower price than specialized retailers (“expect more—pay less”). In this respect, Target is like Warner Bros., a latecomer to animation, which adopted “a ‘utility’ strategy of low cost and differentiation.”32 Target, too, worked to contain costs while introducing novel, premium features.

The model has worked well, with stock returns considerably higher than those of Wal-Mart. Target, which has been described as being “remarkably open to outside influences,” imitates elements of the Wal-Mart model in operations, supply chain, IT, and sales but differentiates itself in merchandising and marketing.33 Given its upscale positioning, Target’s management believes that it does not make sense to follow Wal-Mart into emerging markets at this time. As Greg Steinhafel, chairman and CEO, comments, “One could argue that as India and China get more affluent, they are much more ready for a Target-type strategy.”34 At the same time, Target boasts that its experience with affluent customers makes its model difficult to replicate. As Robert Ulrich, former Target CEO, noted, “I am not saying it can’t happen over time [but] saying that the Yugo is going to turn into BMW is pretty silly.”35

Like EasyJet, E-Mart, a South Korean discount retailer, imported elements of the Wal-Mart and Target models, adapting them to its domestic market. E-Mart offers spacious, Target-like stores but in a Korea-inspired outdoor market atmosphere. It differentiates on the customer interface side, an area where a local player has a natural advantage over a foreign competitor: the chain has bought out the Korean operations of Wal-Mart, which failed to properly adjust its own model to local requirements.36 Other retail importers, such as China’s Wu-Mart, have adopted a similar strategy, with considerable success.

Apple

When Steve Jobs returned as Apple’s CEO, one of the first things he did was to reverse a licensing program that imitated the IBM’s PC approach of letting would-be competitors in on its code in the hope of establishing a new standard. Although the strategy deviated somewhat from that of IBM in that it looked to license the system rather than give it away for free, the result was the same, with clone makers taking a substantial share of its market. Jobs knew the risks based on his own experience: when Apple launched its first personal computer, Asian imitators copied it so fast and furiously that twenty of them were banned by the U.S. International Trade Commission from selling their versions in the United States. Over the past decade, virtually all of Apple’s new products, from the iMac to the iPod and the iPhone, as well as many of its methods and processes, have been imitated soon after launch.

Apple carefully cultivates its image as an innovative company, so much so that in its 2006 product show it dispatched an Elvis impersonator to make the point that an imitation would never match the original. Yet Apple is itself a consummate imitator. John Sculley, one-time Apple CEO, wrote that much of the Macintosh technology “wasn’t invented in the building.”37 The Mac’s visual interface came courtesy of the Palo Alto Research Center, or PARC, a Xerox facility visited by Jobs, who hired some of its researchers. Aspects of the interface—most famously the mouse—were not invented by Xerox but by a scientist named Doug Engelbart, who cooperated with a number of would-be PARC researchers.

Once commercialized, Apple’s application was imitated by Microsoft to create Windows; later versions of both Windows and the Mac operating system include many features originated by others. Years later, Apple would imitate, and improve on, the Gateway retail store concept, only to see Microsoft (led by a Wal-Mart veteran) follow the same path. In 2005, a seller of Lugz boots accused Apple’s advertising agency of copying a Lugz commercial, adding that it was particularly shocked by the imitation because of Apple’s reputation for being “so innovative.”38

More than anything, Apple is a master of assembly imitation : it follows in the paths of many predecessors, which have used existing technologies and materials to generate new technologies by recombining them. Gutenberg’s printing press combined oil-based ink with screw presses used in the making of olive oil and wine. McDonnell Douglas’s DC-3, perhaps the most successful aircraft ever made, rested on a combination of prior innovations that together produced an ingenious and yet simple machine.39 Apple followed similar logic, with Jobs suggesting, “Don’t try to start the next revolution, just crank out smart, affordable consumer products.”40 A master assembler, Apple reserves its creativity for the novel recombination of existing technologies: “Apple is widely assumed to be an innovator . . . In fact, its real skill lies in stitching together its own ideas with technologies from outside and then wrapping the results in elegant software and stylish design . . . Apple . . . is, in short, an orchestrator and integrator of technologies, unafraid to bring in ideas from outside but always adding its own twists.”41

Steve Dunfield, a former Hewlett-Packard executive, offers Taiwan’s Asustek as another example of a PC maker that uses an assembler approach.42 Asustek makes PCs that use a mix of new and existing technologies, innovating on portability, design, and practicality in an affordable package. As one analyst noted, the company broke “the PC industry typical cycle of having to produce something that was always better and faster,” instead “creating something that was more affordable and more portable.”43 Asustek veered away from its motto when it introduced new models every six weeks—a practice that confused consumers—but has since rebalanced.

Companies lacking Apple’s diverse skills tried to combine their skills with those of outside partners, deploying a variant of the assembly–recombination strategy. The weakness of the strategy is that it adds the complexity and transaction cost associated with running an alliance. Microsoft and Samsung aligned with other vendors to offer a full music package to compete with iTunes, but the approach failed, in part because the two companies, successful as they are, have limited alliance capabilities.

“Recombination by partner” did work, however, for SanDisk. CEO Eli Harari commented, “There is no mystery here that what [Apple has] done is worth copying and improving on.”44 An alliance with RealNet-works enabled SanDisk to capture, by the end of second quarter 2006, 10 percent of the market for digital music players, and the company then teamed with Zing Systems and Yahoo! to offer a new wireless device whose capabilities at times surpassed the original. It took a similar approach with the Sansa View, which offered twice the storage capacity of the iPod nano for the same price.45

As in all imitation attempts, successful recombination requires a solution to the correspondence problem or, better yet, a solution that provides a superior fit than the original. Mary Kay Cosmetics married the home party—originated by Tupperware, best known for its food storage containers—with the direct sales model pioneered by Avon in the cosmetics business. With their strong social group element, the home parties were an even better fit with cosmetics than with Tupperware. Further, the combination was consistent with Mary Kay Ash’s vision of her organization as a community of self-enhancing women. Other entrepreneurs would later attempt to imitate the combination of direct sales and social parties and apply it to other market segments, but in the absence of proper fit, many of these efforts fizzled.

Success “Secrets”

Why have some imitators been more successful than others? When one looks closely at the cases described in this chapter, a few factors seem to separate the winners from the losers.

The losers failed to unlock and decipher the black box that contained the explanation for the model’s success. They oversimplified the original, hoping that the replica would produce identical outcomes, but they failed to capture the model’s complexities, including the contingency factors, such as underlying capabilities, that impact a model’s performance. Many thus repeated the error of Fleischer, a one-time leading animation studio. Once it fell behind latecomer Disney, Fleischer tried to copy it, but Fleischer lacked the capability to effectively use new color technology. Further, the Disney approach of “saccharine realism did not fit with that of its animators.”46 Another group, represented by Skybus and Circuit City, attempted a “rational shopper” approach of mixing multiple models, but without resolving the contradictions among them.

In summary, failed imitators did not engage in true imitation and, in particular, failed to solve, or even tackle, the correspondence problem. As a result, they were not able to produce a working replica, let alone adapt the model to changing circumstances as did the Meiji reformers.47

Successful imitators, in contrast, were able to solve the correspondence problem in a number of ways. One group, represented by Ryanair, ValuJet, and Dollar, extended the model in a fashion consistent with, but exceeding, its underlying codified principles. Another group, represented by the likes of JetBlue, Target, and Best Buy, imitated key elements of the model but carefully differentiated themselves in other aspects—in particular, premium service.

The most successful appear to have been the importers, who transplanted the model into another environment. This group performed a sort of arbitrage, reaping the advantages of being a pioneer in a new territory while mitigating risks by replicating something that had proved to work—in an environment that offered similar or superior underpinnings. In that, the importers are, in the words of Lionel Nowell, formerly of PepsiCo, imitators, “because in reality you’re just imitating what is already done, success you [have] had somewhere else.”48 At the same time, they are also innovators, consistent with Levitt’s definition of an innovation not only as something that has not been done before but also as something that has never been done before in a particular industry or market.

Finally, it was clear that our imitation models themselves were consummate imitators. They have imitated others but have done so selectively and via resolution of the correspondence problem, especially regarding vital strategic junctions. This is what Southwest Airlines did when it rectified the critical omission by People’s Express in the form of an underdeveloped information system, and what Wal-Mart did in absorbing elements practiced by first movers while amplifying their value by perfecting its supply chain and rapidly ramping up scale. This is also what Apple did when it learned from failures (such as Gateway’s stores) and successes (such as IBM’s PC) and moved to develop and leverage combinative skills.

At the same time, these model companies were, and made sure they remained, innovative. Our models were, in a word, imovators.

Takeaways

- Imitation approaches vary from a replication and extension of an existing model to differentiation, importation, and recombination.

- Most successful copycats engage in true imitation, which includes deciphering cause and effect and resolving the correspondence problem.

- Most failed copycats engage in rudimentary forms of imitation that fall short of true imitation. They seek to retain their existing systems side by side with an imitated model, or they try to combine contradictory models.

- Imitation models are often themselves consummate imitators as much as innovators; they are, in other words, imovators.