Chapter 4

CEO Perceptiona

Summary

Following the collapse of Enron and several other leading global firms, U.S. legislators responded swiftly with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, a stringent rules-based system widely considered the most comprehensive economic regulation since the New Deal. Research suggests the law may produce serious unintended harmful consequences, resulting in a call for further research to evaluate its impact upon firms. However, the law's impact upon CEO perception is potentially more relevant than its actual costs, as this factor can be expected to directly influence how firms respond to the new law.

This paper contributes to both literature and practice in several ways. First, it conducts a review and analysis of multiple literatures to develop a comprehensive understanding of Sarbanes-Oxley and its potential impact upon firms. Second, CEO perception of the law is evaluated using a random sample survey of Fortune 500 CEOs (n = 206), and the results are discussed in detail. This is the first study to focus explicitly on CEO perceptions of this important law, and is likely to be useful to managers, policymakers, and regulators alike.

Introduction

After the collapse of Enron and reports of accounting fraud at WorldCom, HealthSouth, and other leading firms, Congress enacted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, widely considered the most comprehensive economic regulation since the New Deal.1 Past research has questioned whether the law was necessary, while there is research to suggest that the law may harm firms.2 The salience of these findings is increased by recent research suggesting the role of business is to give primacy to investors.3 Whereas CEOs are likely to possess a superior knowledge of the law, little to no research has sought to document how it is generally perceived by them.

This represents an important topic for several reasons. CEO perceptions of important regulation, especially those strongly held, may influence the quality of firm compliance, at a time when “corporations are under fire.”4 Arguably, managers who believe the law to be beneficial are more likely to champion its objectives, versus complying superficially. Within the context of the global financial crisis, the importance of achieving effective corporate governance structures has attained greater significance.5

Furthermore, CEOs, as leaders of global firms that have withstood enormous challenges in order to implement Sarbanes-Oxley, possess valuable, direct knowledge of the law and its effects. Senior managers, who arguably possess superior knowledge of the strategic challenges and opportunities facing the firm, can be expected to provide valuable insights about the merits of regulatory reform. Research suggests managerial perception to be a vital element of policy analysis, while it also underscores the need for a more extensive use of survey research in particular.6

This paper examines three basic research questions: (1) How do large firm CEOs perceive the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002?; (2) What insights might this reveal about the policy and/or its implementation?; and (3) How might policymakers benefit from this information? The results suggest that large-firm CEOs, in general, perceive Sarbanes-Oxley as a tax upon firms; that their concerns are articulately expressed and supported by relevant research; and that a pronounced fear of incrimination is currently driving perception.7 This study suggests that negative CEO perceptions of this important law pose an unnecessary social cost to investors—equivalent to the degree that they effectively reduce the quality of firm compliance.8

This paper seeks to contribute to the literature on Sarbanes-Oxley in several ways. First, a review of the relevant research on Sarbanes-Oxley is conducted, which draws from multiple literatures. Second, this is the first study to focus squarely on managerial perception of this important legislation, which may be more policy relevant than the actual impact of the law.9 This study seeks to fill an important gap in the literature by empirically documenting how and why senior managers perceive this landmark legislation.

Summary of Relevant Literature

To date, researchers have sought to analyze the impact of the law upon firms. Cohen and colleagues (2007), for instance, find that Sarbanes-Oxley altered the structure of managerial compensation owing to an increase in managerial risk aversion, and reduced research and development spending and capital investments.10 Litvak (2008)11 found that the law was the cause for a reduction in corporate risk-taking, especially for riskier and better-governed firms.

However, the precise impact of the law remains a subject of much controversy. A more recent and growing body of research suggests that, considering all factors, firms and investors are likely to experience negative consequences.12 A particular area of concern within the research has been the law's impact upon corporate risk. For instance, Bargeron, Lehn, and Zutter (2010)13 report a decrease in corporate risk-taking, while Akhigbe, Martin, and Nishikawa (2009)14 suggest an increase in the period immediately following the law's enactment.15

On a related note, Carmona and Trombetta (2008) denote the process by which inflexible, “rules-based” accounting systems can impose significant costs upon firms and the accounting profession in general.16 This infers that regulatory structures may exert an influence upon managerial perception of a law, independent of its content. Sarbanes-Oxley is a rules-based system, characterized by specific criteria, definitions, thresholds, precedents, examples, and implementation guidance.17

Such factors have made it increasingly difficult for firms, as well as the accounting and audit professions to perform their roles effectively.18 Furthermore, there is no clear indication that rules-based systems perform superior to their more flexible—principles-based—counterparts, while there is growing evidence to suggest that they are more costly and less effective.19 These factors suggest several reasons why managerial perceptions of Sarbanes-Oxley may be negative.

Survey

Drawing from a review of the literature, a 25-item survey was developed, as included in the Appendix, to evaluate managerial perception of this important law. The survey was pretested with PhD students and researchers with advanced degrees. In addition, an earlier version was pretested on a convenience sample of 20 firms. The target population is CEOs of the Fortune 1000.20 A random sample of 550 firms was selected, and complete responses were ultimately received from 206 firms.21

Several potential limitations exist. Survey research in general is particularly vulnerable to sampling error (e.g., individuals who differ in important ways are systematically excluded), a nonrandom selection process, and systematic differences between those who did and did not respond to the survey.22 Bias is difficult or even impossible to completely eliminate. To address this issue, the entire population of Fortune 1000 firms was selected for potential survey, and random sampling was employed to eliminate many of the problems associated with more complicated selection methodologies. This effectively rules out the first two potential sources of survey bias.23 To address the third potential source, statistical analysis failed to reveal any systematic difference(s) between participant and nonparticipant firms.

Results

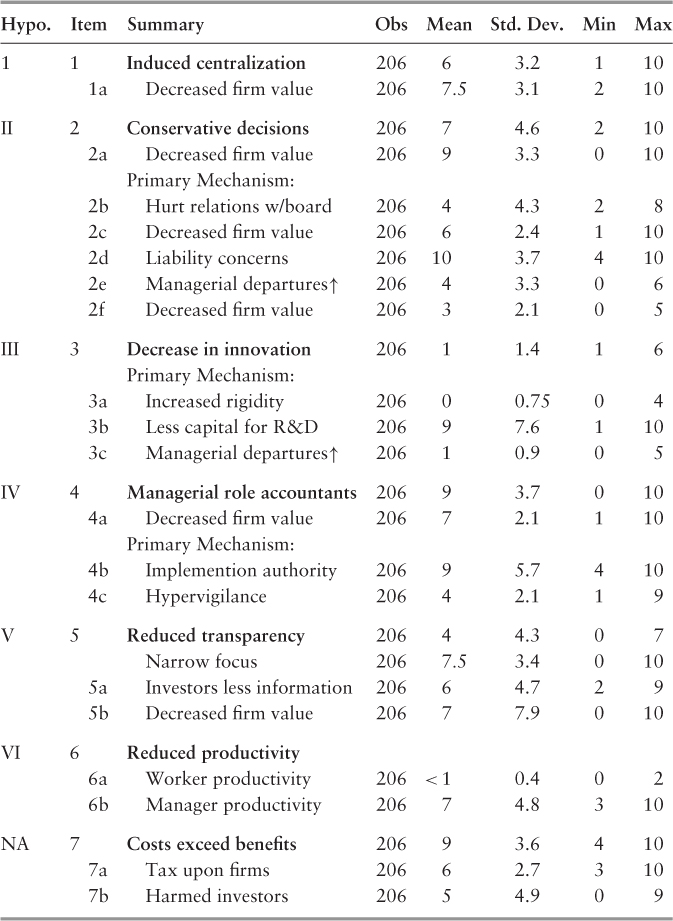

The survey evaluates (1) CEO perception of Sarbanes-Oxley and (2) the rational justification for their views. CEO respondents indicated a strong perception—for example, the mean response was a 9 out of a possible 10—that the costs of the law exceed its benefits. This is another way of stating that it represents a “tax” upon firms, and that it harms more than it benefits investors.24 The survey then sought to clarify what factors were motivating this perception.

The first potential explanatory factor addressed by the survey involves firm centralization. Sarbanes-Oxley compliance is mechanical and prescriptive. Since firms are not free to choose how to achieve the desired objective(s), certain adaptations may be required that reduce any competitive advantage(s). Research suggests that centralization decreases Sarbanes-Oxley compliance costs as well as the risk that a firm will fail to comply.25 Furthermore, stringent repercussions—for example, a criminal court trial and 20 years in jail—potentially await any manager guilty of transgression. Consequently, managers may favor centralization, given that it reduces managerial uncertainty over financial reporting.26

Survey results suggest that CEOs, on average, strongly perceive that Sarbanes-Oxley has induced firm centralization, producing a degree of rigidity that has either “harmed the firm and/or decreased its value.”27 This perception receives at least moderate support from the research, which suggests that centralization may impair the contingent fit between a firm's strategic priorities and its contextual variables.28

The second factor evaluated by the survey is the law's perceived impact upon managerial decision-making. Ensuring board independence is a key objective of Sarbanes-Oxley. However, there is research to suggest this may increase CEO turnover,29 inhibit board monitoring behaviors, and reduce the involvement of the board in managerial decision-making.30 Consequently, board independence may add to the decision making stress of the CEO and decrease her access to required information, biasing decision making in favor of conservatism.

Another prominent concern is the threat of criminal liability. Under section 302—the managerial certification requirement—violations carry a potential fine of $5 million and 20 years in jail, while the scope of activities prosecutable under criminal law has been expanded.31 Prosecutors and juries also received more discretion to determine specific acts that may be prosecuted.32 It is to be expected that managers will seek to reduce their exposure to personal liability, preferring a low-risk, restrained growth strategy over a high-risk plan targeting market dominance.33

Consequently, the results uncovered by the survey fail to surprise. They reveal a strong perception among Fortune 1000 CEOs that the law has biased managerial decision-making in favor of conservatism, and that this has detracted from firm value. The survey also sought to uncover the rational justification for this broadly held perception. CEOs report a strongly felt need to reduce exposure to civil and criminal liabilities, as present under the law. This finding is similar to Litvak (2008), who suggests the law induced a tendency towards “defensive management.”34

More surprisingly, study results suggest large firm CEOs do not perceive of Sarbanes-Oxley as having negatively impacted firm innovation.35 Detractors of Sarbanes-Oxley have long claimed a harmful impact upon innovation, an effect that has been documented in the research literature.36 One reason is that Sarbanes-Oxley increases the marginal cost associated with all types of change—including those yielding tangible improvements—due in part to its extensive documentation requirements. Consequently, firms can be expected to enact fewer changes, constraining innovation.

However, the survey results fail to lend support to this particular point of view. This is likely due to the fact that respondent CEOs are exclusively from large firms, whose R&D spending is less likely to be negatively impacted by relatively costly compliance requirements. In comparison, Sarbanes-Oxley has been shown to have a pernicious impact upon young, small growth firms.37

Arguably more intuitive are the survey results suggesting that auditors gained managerial influence under Sarbanes-Oxley, which is perceived as having harmed firms. Even before Sarbanes-Oxley, research documents that auditors played an influential role in the managerial decision-making process.38 Furthermore, managerial accounting has long been considered important to the development of firm strategy.39 The law bolsters these relationships by defining internal controls to encompass nearly every firm process.

Since accounting firms monitor compliance and have the power to punish malefactors, they received no small increase in prestige and earnings.40 Anecdotal accounts lend further support to the survey results suggesting auditors now influence both the development of firm strategy and a broad range of managerial decisions.41 In rational justification of this perception, respondent CEOs are relatively homogenous in their view that accounting firms received a generous increase in implementation authority due to Sarbanes-Oxley, and that this has been abused.42

The survey also evaluates CEO perception of the law's ability to achieve increased transparency. Audit quality depends upon having access to the right information,43 whereas rules-based standards are likely to impose a rigid, one-sized-fits-all accounting approach that deters a comprehensive and accurate disclosure.44 Furthermore, highly prescriptive laws may make it more difficult for accountants and auditors to detect and prevent inappropriate behavior,45 and research suggests that firms have switched, rather than reduced, their earnings management practices, so as to avoid detection.46

Even regulators admit the immensely difficult, if not impossible, task that the average investor faces in trying to comprehend financial statements in the post–Sarbanes-Oxley–era.47 While the information quality of firms' financial statements was allegedly decreasing,48 investors were led to place greater trust in the general reliability of financial reporting,49 inferring a decrease in transparency. The idea that important laws can exert significant effect contrary to their intended consequence has been documented in prior research, and therefore is not entirely surprising.50

Survey results reveal a moderately held perception among large firm CEOs that Sarbanes-Oxley has effectively decreased transparency.51 Respondent CEOs, in general, suggest two contributing factors: (1) that the law's focus on internal controls is overly narrow, and (2) that firm disclosures have become less useful to investors, thus making it more difficult to monitor firm managers effectively (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1 Summary Statistics, Overall Sample

The findings uncovered in this part of the study receive moderate support in the research literature. Under rules-based regimes, accountants are prone towards a mechanistic application of the law,52 and consider rigid adherence an indispensable means of avoiding incrimination.53 Consequently, financial reports are now longer, more complex, and utilize extensive footnotes.54 Firms' 10-K reports in the Dow Jones industrial average have doubled in average length over the past six years.55 Some firms now routinely disclose nonmaterial, insignificant bookkeeping weaknesses that possess only a remote chance of affecting financial statements.

The outcome is a significant increase in the volume of disclosure-related activities—so as to ward off potential lawsuits and/or placate the firms' auditors56—but a decrease in their comprehensibility. The result is a dilution in the quality and usefulness of financial statement information, increasing monitoring costs.57

Discussion

Much research on Sarbanes-Oxley has focused on accounting costs, while little is known about how CEOs, in general, perceive the law, or more importantly why. This study analyzes managerial perceptions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. A key finding is that managerial fear of incrimination influences, at a deep level, CEO perception. Inflexible rules, coupled with greater opportunities for prosecution and stiffer penalties, negatively impact CEO perception of this important law. Given the research suggesting that stricter regimes are not unequivocally superior to principles-based standards (e.g., Trombetta 2001),58 arguably a principles-based implementation may achieve the desired objectives with reduced social costs.

In summary, the survey suggests that large firm CEOs consider that the costs of Sarbanes-Oxley outweigh any potential benefits, such that it represents a tax upon firms. Furthermore, the survey reveals that this negative perception is due to three primary factors, which are generally believed to have been caused by the law:

This study also increases our understanding of the potential effects of rules-based systems upon firms and CEOs. CEOs broadly report that it is the law's harsh legal repercussions—its reliance upon inflexible rules versus principles—and not any disagreement with its specific objectives that currently fuels the negative perception of this landmark legislation. Although research demonstrates managerial perception to be a critically relevant element of policy analysis,59 all too often CEO concerns about Sarbanes-Oxley have been dismissed as self-interested “carping.”60 An important takeaway of this study is that CEO concerns about this important regulation, rather than reflecting exaggerated, unfounded criticism, are broadly supported in the academic literature, and therefore appear to have a strong rational basis. Arguably, they deserve closer attention.

Managerial scandals at Enron, WorldCom, and other leading firms, helped to motivate Sarbanes-Oxley and tarnished the reputation of the public firm CEO. Arguably, a major outcome was that CEOs were afforded a less central role in important policy deliberations, especially those pertaining to corporate governance. Perhaps it is time for this to change.

Appendix to Chapter 4

Both the survey instruments employed in this study, as well as the statistical analyses utilized to infer meaning to the results are set forth in the following section. A careful analysis of the survey instrument and the results achieved strongly suggest that the study captured something other than CEO antipathy for a stringent regulation. Furthermore, it bears noting that CEOs are inherently predisposed in favor of regulatory reform enhancing firms' ability to raise capital in the public markets, as this constitutes a critical factor for operating success. Because Sarbanes Oxley, through enhancements in corporate transparency, promised to ease the burden of raising public capital, the status quo expectation would be for CEOs to support—rather than oppose—the law.

Survey Instrument

The general purpose of this survey is to better understand and appreciate the overall impact that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 has had upon your firm. In particular, we are seeking to evaluate the nonpecuniary costs that the law has imposed on firms. Nonpecuniary costs, a term originating in the law, refers to a loss that cannot be quantified monetarily, but which nevertheless detracts from the well-being or utility of the firm. Since they are not traded in markets, no market price exists by which to calculate damages. Research suggests several reasons why it may be difficult for managers to recognize even significant nonpecuniary costs incurred by the firm as a result of a particular regulation. As a result, this study seeks to evaluate the hypothesis that firms have incurred potentially significant nonpecuniary costs as a result of Sarbanes-Oxley.

In making your responses, please focus on your own firm's experiences, versus what you may have read or discussed with colleagues. This survey may be completed in as little as 20 minutes, depending upon your answers.

Survey Items

Before beginning, please attest that you have a high level of familiarity with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act as well as the impact it has had upon your firm. If you do not, please do not complete the survey.

In responding to the remaining survey items, please adhere to the “0 to 10” scale in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Survey Response Scale

| Response | Interpretation | Effect perceived as… |

| 0 < y ≤ 1 | No effect (untrue) | NA |

| 1 < y ≤ 4 | Effect (true) | Moderate |

| 4 < y ≤ 7 | Effect (true) | Significant |

| 7 < y ≤ 10 | Effect (true) | Dominant |

For instance, if you both observe an effect and believe that it is “dominant” you would respond to the question by inserting either an “8,” “9,” or “10.” Conversely, if there is no observed effect (or N/A), you would respond with a “0.” All items relate to the firm where you are principally employed. Prior to responding, please read carefully the explanations and definitions that were provided separately. All descriptions and definitions were taken from the study text and various business dictionaries, and are necessary to understand the question in its proper context. Results are summarized in Tables 4.3 through 4.5.

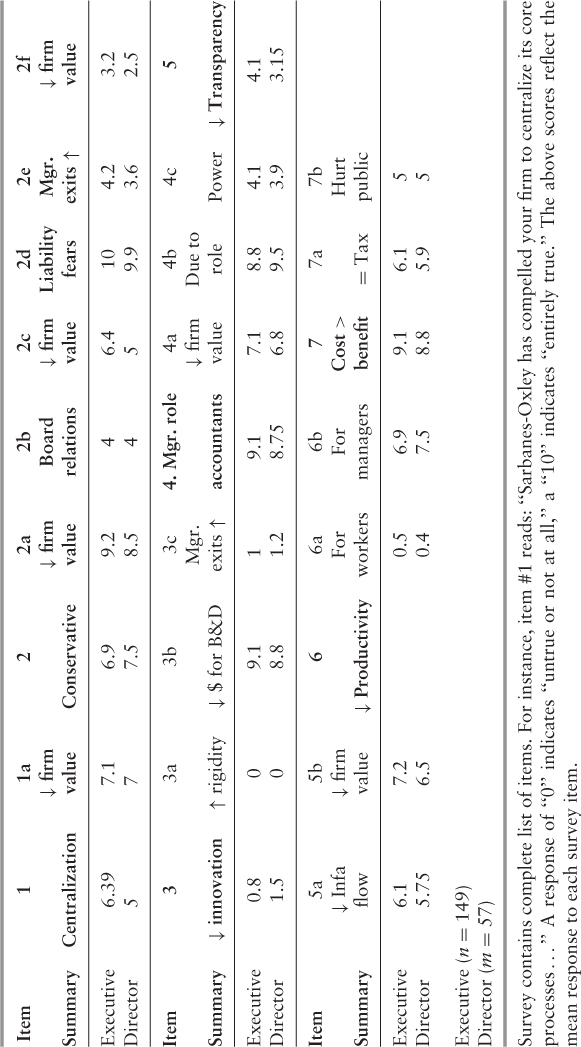

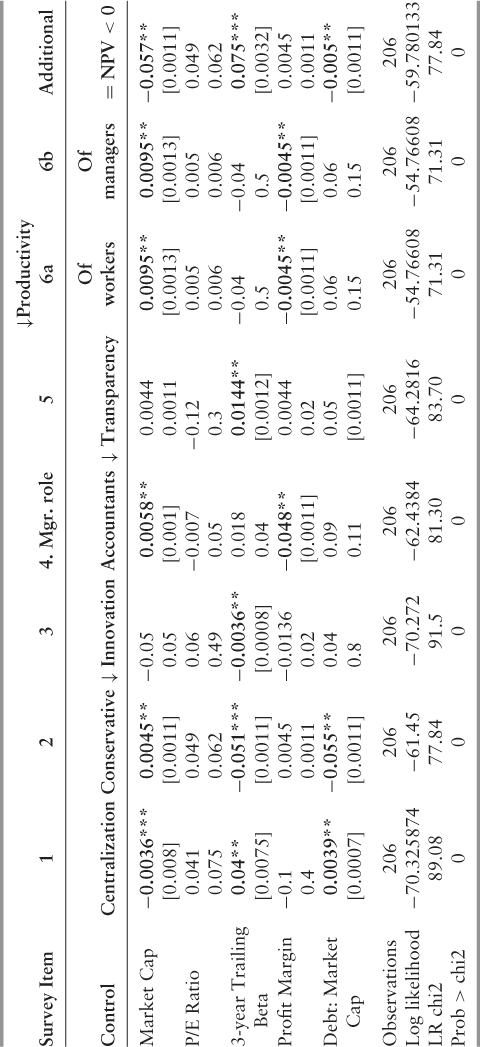

Table 4.3 Summary of Results, Mean by Function

Survey contains complete list of items. For instance, item #1 reads: “Sarbanes-Oxley has compelled your firm to centralize its core processes…” A response of “0” indicates “untrue or not at all,” a “10” indicates “entirely true.” The above scores reflect the mean response to each survey item.

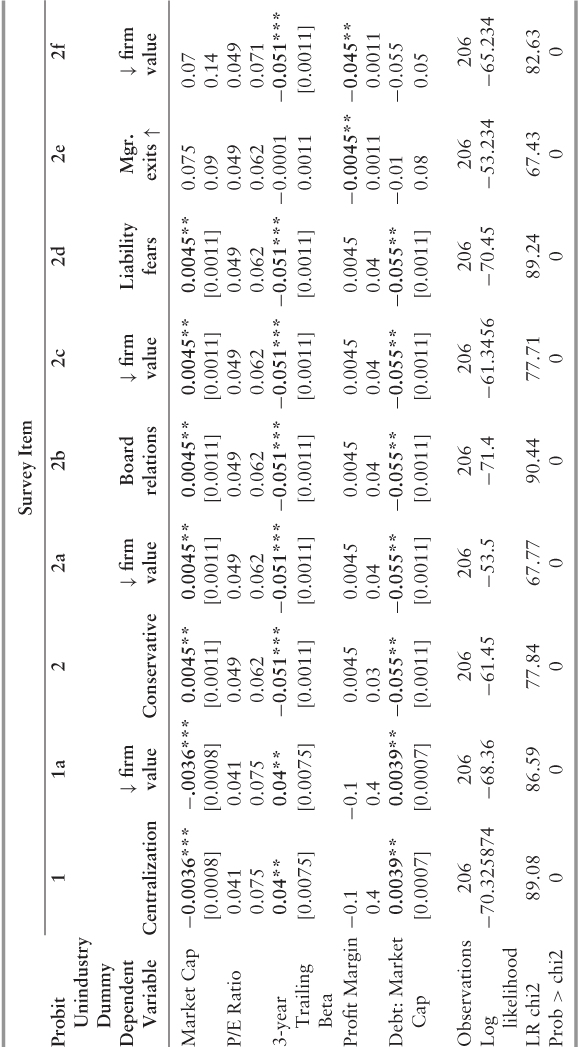

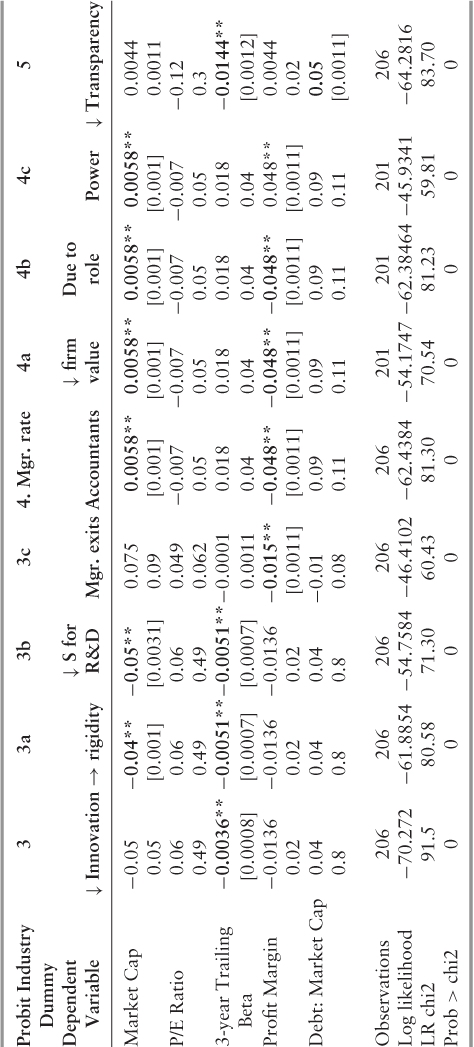

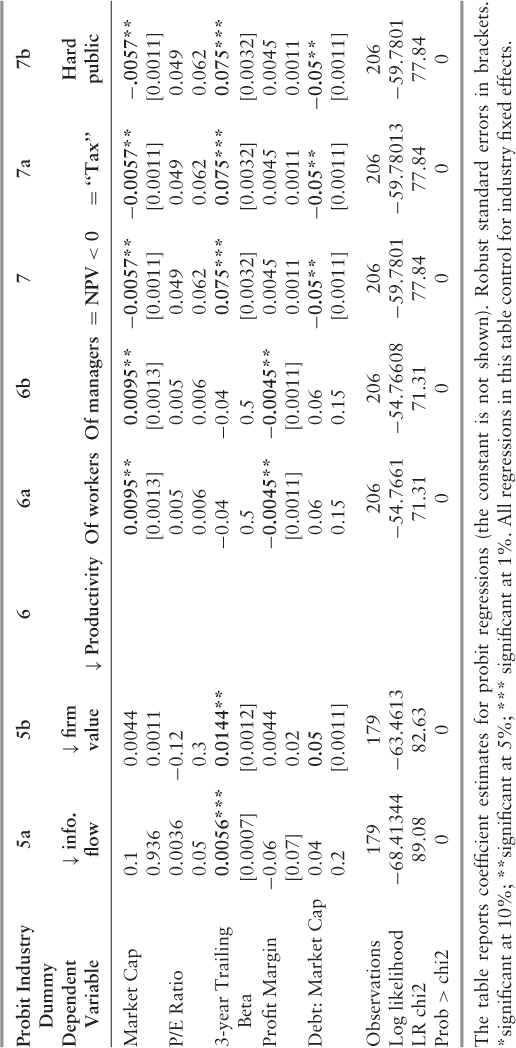

Table 4.4 Ordered Probit Regression Results

Table 4.5 Summarized Ordered Probit Regression Results for Main Hypothesis

Notes

1 R. McAfee, “The Real Lesson of Enron's Implosion: Market Makers Are in the Trust Business.” The Economists' Voice, 1, no. 2 (2004).

2 M. DeFond and J. Francis, “Audit Research after Sarbanes-Oxley,” Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 24 (2005): 5–30; C. Baker, “Ideological Reactions to Sarbanes–Oxley.” Accounting Forum, 32, no. 2 (2008): 114–124. In spite of occasional high-profile corporate failures and/or accounting scandals, the annual rate of audit failures, defined in terms of successful litigation or U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) sanctions, is nearly zero.

3 A. M. Adam and T. Shavit, “Roles and Responsibilities of Boards of Directors Revisited in Reconciling Conflicting Stakeholders' Interests While Maintaining Corporate Responsibility,” Journal of Management and Governance 13 (2009): 4.

4 P. Monfardini, W. C. Zimmerli, K. Richter, and M. Holzinger, “Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance.” Journal of Management and Governance, 13, no. 4 (2009).

5 M. Hilb, “Redesigning Corporate Governance: Lessons Learnt from the Global Financial Crisis.” Journal of Management and Governance, 2010.

6 P. Buckley and M. Chapman, “The Management of Cooperative Strategies in R&D and Innovation Programmes,” International Journal of the Economics of Business 5 (1998): 369–81; H. L. Tosi, Jr., “Quo Vadis? Suggestions for Future Corporate Governance Research.” Journal of Management and Governance 12 (2008): 2.

7 A potential insight of May (1995) is that managerial perception and decision making are influenced by the significant increase in personal liability exposure managers that incur under Sarbanes-Oxley.

8 Perhaps by incorporating CEOs as stakeholders in the regulatory development and implementation process, it may be possible to enhance such perceptions.

9 Buckley and Chapman, “The Management of Cooperative Strategies.”

10 D. Cohen, A. Dey, and T. Lys, “The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002: Implications for Compensation Contracts and Managerial Risk-Taking.” Working Paper available at, SSRN, 2007. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1027448.

11 Litvak, K., “Defensive Management: Does the Sarbanes-Oxley Act Discourage Corporate Risk-Taking?,” 3rd Annual Conference on Empirical Legal Studies Papers available at SSRN, 2008. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1120971.

12 For a discussion, see: H. Li, M. Pincus, and S.O. Rego, “Market reaction to events surrounding the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002,” Journal of Law and Economics 51 (2008): 111–134; I. X. Zhang, “Economic Consequences of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 44 (2007): 74–115; Z. Rezaee and P.K. Jain, “The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and Security Market Behavior: Early Evidence,” 23 Contemporary Accounting Research (2006). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=904649 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.498083; V. Chhaochharia and Y. Grinstein, “Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Impact of the 2002 Governance Rules.” 62 Journal of Finance (2007), 1789–1825. The law's potential for positive, unintended effects are not covered in this analysis though for purposes of evaluation these are limited strictly to its ability to achieve the intended objectives.

13 L. L. Bargeron, K. M. Lehn, and C. J. Zutter, “Sarbanes-Oxley and Corporate Risk-Taking,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 49 (2010): 34–52.

14 A. Akhigbe, A. D. Martin, and T. Nishikawa, “Changes in Risk of Foreign Firms Listed in the U.S. Following Sarbanes-Oxley.” Journal of Multinational Financial Management 19 (2009): 193–205.

15 Underscoring the broad and fundamental disagreement over Sarbanes-Oxley, John, Litov, and Yeung (2005) argue that regulation that seeks to protect investors by improving governance mechanisms will both increase risk and improve firm value.

16 S. Carmona and M. Trombetta, “On the Global Acceptance of IAS/IFRS Accounting Standards: The Logic and Implications of the Principles-Based System.” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 27, no. 6 (2008).

17 See M.W. Nelson, “Behavioral evidence on the effects of principles- and rules-based standards,” 17 Accounting Horizons (2003): 91–104 for a discussion on rules-based accounting systems.

18 C. Baker and R. Hayes, “The Enron Fallout: Was Enron an Accounting Failure?” Managerial Finance 31 (2005): 5–28.

19 M. Trombetta, “The Regulation of Public Disclosure: An Introductory Analysis with Application to International Accounting Standards.” In Contemporary Issues in Accounting Regulation, eds. S. McLeay and A. Riccaboni (Boston: Kluwer, 2001), 119–134; J. Ronen, “Policy Reforms in the Aftermath of Accounting Scandals,” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 21 (2002): 281–286.

20 The most recent list—as of the original date of publication—of the Fortune 1000 may be found at the following Web address. http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/2009/full_list/.

21 The response rate benefited from several helpful factors: Respondents were permitted ample time to respond, during which period numerous follow-up efforts were made, and support from professional colleagues was also enlisted in order to encourage target firm responses.

22 F. Fowler, Survey Research Methods, 4th ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008).

23 Ibid.

24 Respondents were asked about the extent to which they agreed with a particular proposition (for example, “The costs of the law exceed its benefits…”). A mean response of a “9” indicates near-total agreement. The law is perceived as a tax to the extent that it is seen as harming firms without actually helping them.

25 A. Marchetti, Sarbanes-Oxley Ongoing Compliance Guide: Key Processes and Summary Checklists (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007).

26 U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), Integrated Approach, Accountability, Transparency, and Incentives Are Keys to Effective Reform (Washington, DC: GAO, 2002).

27 Rigidity in this sense is believed to impair the firm's ability to respond to its competitive environment.

28 J. Jermias and L. Gani, “Integrating Business Strategy, Organizational Configurations, and Management Accounting Systems with Business Unit Effectiveness: A Fitness Landscape Approach,” Management Accounting Research, 15, no. 2 (2004): 179–200.

29 V. Laux, “Board Independence and CEO Turnover,” Journal of Accounting Research, 46, no. 1 (2008): 137–171.

30 R. Clark, “Corporate Governance Changes in the Wake of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act: A Morality Tale for Policymakers Too.” Georgia State Law Review, 2005, 251.

31 Under Sarbanes-Oxley, managers who do not knowingly intend to engage in fraud can now be prosecuted for fraud. Prosecutors no longer have to prove intent.

32 C. Lerner and M. Yahya, “‘Left Behind’ after Sarbanes-Oxley.” Regulation, 30, no. 3 (2007): 44–49.

33 For example, Zhang (2007) estimates that, because of Sarbanes-Oxley, the market capitalization of U.S. public firms fell by $1.4 trillion. With approximately 10,000 publicly traded firms, the estimated net effect is nearly $140 million per firm, possibly caused by a (suboptimal) reduction in risk.

34 Like defensive medicine, defensive management refers to practices strictly intended to shield the actor from criminal and/or legal liabilities.

35 This hypothesis was not supported (ux = 1; SDx = 1.4). Thus, it cannot be concluded that Sarbanes-Oxley has negatively impacted the rate of firm innovation.

36 See, for instance: Litvak (2008); Lerner and Yahya (2007) and H. Shadab, “Innovation and Corporate Governance: The Impact of Sarbanes-Oxley,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business and Employment Law 10 (2008): 955–1008.

37 M. Wintoki, “Corporate Boards and Regulation: The Effect of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Exchange Listing Requirements on Firm Value,” Working Paper, available at SSRN, 2007. http://ssrn.com/abstract=968413.

38 S. Salterio and L. Koonce, “The Persuasiveness of Audit Evidence: The Case of Accounting Policy Decisions,” Accounting, Organizations, and Society 22, no. 6 (1997): 573–588.

39 R. Kaplan, “The Competitive Advantage of Management Accounting.” Journal of Management Accounting Research 18 (2006): 127–135.

40 For a discussion, see: A. Pollock, Addressing the unintended burdens of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act. Testimony to the House Government Reform Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs. (2006) www.aei.org/speech/24156 and, J. Lyon & M. Maher, “The importance of business risk in setting audit fees: Evidence from cases of client misconduct,” Journal of Accounting Research (2005) 43: 133–151.

41 D. Henry, M. France, and L. Lavelle, “The Boss on the Sidelines: How Auditors, Directors, and Lawyers Are Asserting Their Power.” BusinessWeek, April 25, 2005.

42 This refers largely to the belief that accounting firms have taken advantage of Sarbanes-Oxley's ambiguous provisions in certain areas (for example, Section 404) to increase their own profits by requiring unnecessary testing.

43 R. Simnett, “The Effect of Information Selection, Information Processing, and Task Complexity on Predictive Accuracy of Auditors,” Accounting, Organizations, and Society 21, no. 7/8 (1996): 699–719.

44 Carmona and Trombetta.

45 C. Baker and R. Hayes.

46 D. Cohen, A. Dey, and T. Lys, “Trends in Earnings Management and Informativeness of Earnings Announcements in the Pre- and Post-Sarbanes-Oxley Periods.” Working Paper available at SSRN, 2005. http://ssrn.com/abstract=658782.

47 C. Hewitt, Speech by SEC Staff: Remarks to the Practicing Law Institute's SEC Speaks Series. Washington, DC: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2007. www.sec.gov/news/speech/2007/spch020907cwh.htm.

48 T. J. Rodgers, “FASB: Making Financial Statements Mysterious.” Cato Institute Briefing Papers. No. 105, 2008. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

49 A. J. Pollock, Speech: “Has Sarbanes-Oxley Harmed Entrepreneurs?” Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 2007, www.aei.org/speech/26375.

50 R. McAfee and N. Vakkur, “The Strategic Abuse of Antitrust Laws.” Journal of Strategic Management Education 1 (2004): 1–18.

51 Relevant summary statistics are ux = 4 out of 10; SDx = 4.3 also out of 10. The mean is low and the standard deviation high relative to other survey items that proved significant.

52 Carmona and Trombetta.

53 Henry, France, and Lavelle.

54 Baker, C.

55 A. J. Radin, “Have We Created Financial Statement Disclosure Overload?” The CPA Journal Online, 2007, www.nysscpa.org.

56 Radin.

57 To the degree that investors respond—perhaps out of frustration or false assurances—by reducing monitoring activities, there is a paradoxical increase in the likelihood of fraud. For a discussion, see: P. Povel, R. Singh & A. Winton, “Booms, busts, and fraud,” 20 Review of Financial Studies (2007):1219–1254.

58 M. Trombetta, “The Regulation of Public Disclosure: An Introductory Analysis with Application to International Accounting Standards,” in Contemporary Issues in Accounting Regulation, eds. S. McLeay and A. Riccaboni (Boston, MA: Kluwer, 2001), 119–134.

59 P. Buckley and M. Chapman, “The Management of Cooperative Strategies in R&D and Innovation Programmes,” International Journal of the Economics of Business 5 (1998): 369–81.

60 See, for instance: A. Stone, “SOX: Not So Bad After All?” BusinessWeek, August 1, 2005.

a This article originally appeared in the Journal of Strategic Management Education under the title “CEO Perception and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.”