Introduction

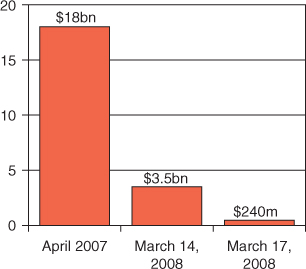

Several factors suggest that the U.S. financial markets may be more in need of transparency today than at any time in past history. As just one of many potential examples, a looming credit crisis forced the sale of Bear Stearns Co., the fifth-largest U.S. investment bank. Its stock market value reached $18 billion in 2007, then fell to $3.5 billion on March 14, 2008.1 Two days later, the firm was rescued by JPMorgan Chase for a mere $236 million2—a transaction made possible only with a $30 billion infusion from the Federal Reserve.3

Market Capitalization of Bear Stearns ($bn)

Source: NYSE.

Regrettably, the ill-fated rescue of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan Chase—with the help of the U.S. taxpayer—further decimated the economic climate, and added to the number of serious and costly policy blunders committed by U.S. regulators since the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. This most recent blunder, contrary to addressing the profound, underlying policy issues motivating corporate executives to mismanage firm risk(s) in heretofore unseen levels with catastrophic consequences to shareholders and the general public, offered a veiled assurance to other would-be misanthropic executives that the financial responsibility for any additional, egregious acts of corporate irresponsibility would be borne squarely upon the shoulders of (innocent) taxpayers. As a result, large firms—those of central significance to the U.S. economy—received yet another assurance from regulators that the moral and financial responsibility for the negligent and/or criminal mismanagement of firm assets would, as a general rule, be passed on to the general public, and not to those actually responsible.

The Federal Reserve was forced to make an additional $400 billion available to stem the tide of rising bank failures.4 The failure of IndyMac meant that thousands of individuals with large deposits would receive just 50 cents on the dollar for every dollar over the $100,000 limit.5 This period has been described as a “self-reinforcing downward spiral of higher haircuts, forced sales, lower prices, higher volatility, and still lower prices.”6 The cause: a fundamental lack of confidence,7 precipitated by a lack of transparency, leaving investors unable to evaluate risk or monitor management.8

Contributing factors include fundamental changes in the housing market (e.g., reduced interest rates, inflationary housing prices, innovative mortgage products, relaxed underwriting standards), and an increasing reliance upon leverage and complex derivative instruments.9 The result is that current methods for conceptualizing and measuring transparency have proved less than adequate, signaling the need for fundamental improvements.10

The unmistakable result of current U.S. regulatory policy—as represented most clearly by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Sarbanes-Oxley)—has been to create a moral hazard of heretofore unseen proportions: a situation in which the general public (the taxpayer) is forced to accept financial responsibility, if not moral culpability, for the criminal wrongs of America's corporate elite. The architecture of the American corporation is wholly by design and not accidental: Shareholders hire managers who are to act as professional stewards of the firm's assets.

To ensure that this function is fulfilled and that managers act in the best interests of shareholders—who are the firm's owners—managerial actions, at least in theory, are continuously monitored, either by shareholders directly or by shareholder proxies. One particularly obvious monitoring device intended expressly for the purpose of monitoring firm management is the board of directors, whose members are elected by shareholders and whose purpose is to ensure that managerial action is congruent with shareholder interests.

Consequently, the primary objective of regulatory policy in this regard is to enable and to embolden shareholders, as owners of the firm, to monitor corporate managers more effectively—that is to say, accurately—and with increasing efficiency—for example, such that the primary monitoring functions consume minimal firm resources. Within the modern taxonomy, the equivalent (regulatory) objective is more often stated in the following way: Regulatory policy seeks to facilitate corporate transparency, essentially to protect the interests of shareholders and the general public from the potential wiles of (deceitful) managers.

It is important to note that, as an empirical fact drawing from many decades of empirical data, the vast majority of corporate managers are not in fact law violators. In spite of this, “transparency”—a condition in which the remote, inner workings of an organization are ostensibly and reliably visible to external, interested parties—retains value even when it can be shown that the overwhelming majority of corporate managers, in effect, lack mens rea (i.e., criminal intent). Corporate transparency retains value in such cases in that those who invest in public corporations generally speaking do so in order to maximize their return on investment. For instance, over the long run the expected return of investing in a diversified portfolio of equities is greater than the expected return resulting from stuffing cash in a mattress, as one example.

Transparency not only decreases the probability that firm managers will violate the law—for example, largely by increasing the likelihood that malefactors will be caught—but it simultaneously increases the probability that managers will act in accordance with the interests of shareholders by engaging in the very types of behaviors that enhance the equity value of the firm. Consequently, in objective terms, the value of corporate transparency is actually multifaceted.

However, since the objective of this book is to empirically analyze the U.S. regulatory regime—vis-à-vis this sought-after condition referred to as “corporate transparency”—the focus is on the former rather than the latter purpose of transparency. This is largely because U.S. regulators have actively sought, through various interventions and at a great cost—both direct as well as indirect—to enhance corporate transparency as a means of reducing corporate malefaction. Consequently, this book seeks to analyze the policy impact of this era of (primarily financial and accounting) regulation. In this regard, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the most exhaustive securities regulation since the New Deal era, is especially noteworthy. Sarbanes-Oxley—more so than Dodd-Frank—is the lustrous “crown jewel” in the modern era of U.S. financial securities regulation. More than any other single piece of legislation, it represents the official position of U.S. policymakers—for better or for worse—toward economic competition within the paramount context of the modern, public corporation.

A major assumption of the authors is that comprehending U.S. regulatory policy—and its significant impact upon global financial markets11—is simply impossible without first grasping a basic appreciation of Sarbanes-Oxley. To relay a relevant personal anecdote, while covering a recent global conference sponsored by the Milken Foundation—very likely the world's leading think-tank—I conversed with a senior Goldman executive about the recent series of financial crises, many of which have involved financial institutions.

Frustrated that Sarbanes-Oxley—given its focus upon risk management—had not played an active role in that day's discussions, I queried the executive about his views on the law, and its influence upon the ensuing series of financial crises. His reply to me—“Sarbanes-Oxley? Oh, you mean that accounting law?”—was broadly indicative of a myopic trend that has severely detracted from nearly every serious effort to comprehend the root cause of the current global economic malaise: an artificial limitation of the focus to regulatory policies enacted within the past 12 months.

Individuals, including CEOs of global firms, leading policy makers, and even members of Congress, whose knowledge and understanding of U.S. regulatory policy is limited to those policies enacted in the past quarter century, will be entirely unable to understand the underlying roots of the modern demise of the U.S. economic engine and the ensuing effect on global economic conditions. Absent this understanding, policy makers will continue to adhere to untested assumptions—or worse, to implement as policy measures that cannot be justified on a rational basis—even when there is ample empirical evidence to suggest the failure of these assumptions as all but inevitable. Sarbanes-Oxley, as the most sweeping regulatory change since the New Deal, clearly fits in that category.

While it is true that a host of other policies have been enacted since 2002, none have been so comprehensive, sweeping, or indicative of U.S.—and therefore to a large extent, global—regulatory policy as has Sarbanes-Oxley. Furthermore, the subsequent policy enactment of Dodd-Frank adheres to the same narrow regulatory formula as Sarbanes-Oxley, and thus this discussion—in many, if not most, aspects—pertains equally to both laws. As such, in order to understand how we arrived at this critical juncture, it is essential to first gain an appreciation of the true antecedents—that is to say the etiology—of the modern economic crisis.

A primary assumption of this treatise is that the current economic malaise is largely—though not entirely—a result of regulatory insipience stemming in part from a total inability or unwillingness to either conceive of or to empirically evaluate (alternative) theories not supported by the modern zeitgeist. As Albert Einstein once said, “Whether you can observe a thing or not depends on the theory which you use.” It is the theory which decides what can be observed.12 The modern policymaker—as predicated largely on the basis that it is in fact “modern”—tends to overestimate the limits of its own capacity to attain knowledge, including an ability to produce, at will, desired changes in the global economy without producing even more rueful, unintended consequences.

Well-intentioned regulations end up having undesirable—at times disastrous—and wholly unintended effects. If anything, the financial turmoil and havoc wreaked upon the global economy by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 should inspire in the objective observer a profound sense of humility: The extent of our knowledge is much more tepid than we might otherwise have been led to believe. Former SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt—one of the most vocal supporters of Sarbanes-Oxley–era regulation—once stated, “Today, American markets enjoy the confidence of the world. How many half-truths, and how much accounting sleight of hand, will it take to tarnish that faith?”13

Given the financial turmoil generated by this era of regulation, a much more humble—and honest—question would have been, “How many more failed accounting regulations are necessary to destroy faith in the U.S. financial markets?” In a single decade, failed regulation has done far greater damage to the U.S. economy—and by extension to the global economy—than the sum total of criminal activities committed by corporate executives, for whom there were already ample legal restraints.

Regrettably, Sarbanes-Oxley's most ardent supporters—of whom Arthur Levitt is only the most prominent and the most visible—who championed its legislative enactment and successfully beat back any subsequent efforts at its repeal (as the facts later became more widely known) have yet to publicly evince either remorse or culpability for the clear and rueful effects it has produced, not to mention its complete and total failure to achieve any of the desired or intended objectives. Arguably, any aspirations for the future of the U.S. economy may very well rest upon the abilities of Mr. Levitt and his like-minded colleagues to objectively re-evaluate the normative role of comprehensive regulatory changes. Unfortunately, that has yet to occur.

As Einstein once aptly noted: “So many people today—and even professional scientists—seem to me like someone who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest.”14 The reference is apt in that Einstein was referring to those for whom learning and studying is a profession, and not those who lack educations. In a similar manner, the 2010 enactment of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act suggests that policy makers learned nothing from the palpable failure of the U.S. regulatory mélange prior to the global financial crisis. Rather than work feverishly to construct a new foundation, as needed to correct the existing fundamental flaws, they instead redoubled their efforts, further imposing upon the global economy an inefficacious regulatory framework that, it may reasonably be argued, enhances economic volatility, and punishes productivity, while producing no clear winners.

Restoring order to the U.S.—and likewise to the global—economy requires, at the minimum, a basic understanding of the etiology of the recent crisis. While failed regulatory policy has not been the sole cause of the ensuing global chaos, this book seeks to argue that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002—like its successor the Dodd-Frank Act—inadvertently contributed to the present turmoil thus enabling it to spread.15 Through this book, readers receive a persuasive, empirically-based, and objective analysis as to the origins of these critical developments. Furthermore, it also provides a clear outline of suggested improvements, as urgently needed to turn the tides of global economic instability.

A popular saying suggests that when the U.S. sneezes the world catches a cold. Because America's economic future now hangs in the balance, the global relevance of this book is clear. As a result, it is dedicated to all those who share the slightest concern for the future of the U.S. and global economy, and is intended as a vital means of reigniting global economic progress through improved policy. It constitutes an invitation not only to Americans but to individuals of all nationalities and political persuasions to set policy differences aside in order to work together for positive change. Please don't make the mistake of expecting your elected representatives to take the first step, it will be too late. Start today: Read this book, get informed, and contribute meaningfully to the world we share.

1. L. Steffy, “Law Can't Stop Failure,” Houston Chronicle, March 20, 2008.

2. CBS/AP, “Wall Street Mixed on Bear Stearns Collapse,” March 17, 2008.

3. D. Guodong, “Troubled U.S. Financial Market Raises Worries of Deeper Recession,” China View (Washington), March 22, 2008. www.chinaview.cn.

4. BBC, “Rescue for Troubled Wall St. Bank,” March 17, 2008. http://news.bc.co.uk/l/hi/business/7200038.stm.

5. Guodong, “Troubled US. Financial Market Raises Worries.”

6. Testimony of Timothy F. Geithner, President and CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs of the U.S. Senate on Actions by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in Response to Liquidity Pressures in Financial Markets (April 3, 2008).

7. For a discussion on the underlying mechanics, see R. P. McAfee, “The Real Lesson of Enron's Implosion: Market Makers Are in the Trust Business,” The Economists' Voice 1, no. 2 (2004): Article 4.

8. A competing argument may be that these problems were not the result of a transparency deficiency. While this is relatively complicated, transparency was clearly lacking in terms of balance-sheet financing and firm risk, which prevented investors from being able to effectively monitor managerial decision making.

9. See, for example, The President's Working Group on Financial Markets (2008), Policy Statement on Financial Market Developments; R. Herz, “Lessons Learned, Relearned, and Relearned Again from the Credit Crisis: Accounting and Beyond,” Financial Accounting Standards Bureau (FASB): Chairman's Office, September 18, 2008.

10. For instance, to the degree that transparency results in uncertainty and stress it may have a deleterious effect on decision making. See J. Ledo, J. O. Chinnis Jr., M. S. Cohen, and F. F. Marvin, “Influence of Uncertainty and Time Stress on Decision Making.” Decisions Science Consortium, Inc., Reston, VA, 1996. www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a306834.pdf.

11. P. Yeoh, “Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: Learning from the Competing Insights.” International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 7 (2010): 42–69.

12. A. Einstein, as quoted in A. Salam, Unification of Fundamental Forces: The First 1988 Dirac Memorial Lecture (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

13. As quoted in Alex Berenson, The Number: How the Drive for Quarterly Earnings Corrupted Wall Street and Corporate America (New York, NY: Random House, 2003), xx–xxi.

14. Quotation from a letter to Robert A. Thorton, Einstein Archive (EA-674), Hebrew University, Jerusalem, December 7, 1944.

15. Yeoh, “Causes of the Global Financial Crisis,” 42–69.