One World, Many Landscapes

Seasons and a Sense of Place

- In the summertime, at high altitude, wildflowers burst into color—like this lupine I found in mid-August near Tuolumne Meadows in the High Sierras.

120mm, 1/90 of a second at f/5.3 and ISO 100, hand held

- Pages 146–147: I created this image by shooting north from near Furnace Creek in Death Valley National Park during the dark of the moon in late February. I set my camera up on a bluff where I didn't think it would be disturbed. I used a portable AC power supply and an AC adapter so I had enough “juice” to last for many hours of continuous photography, then set the camera on Manual exposure and Bulb. I used an intervalometer—a programmable remote timer—to shoot the images through most of the night. While the camera was working I was even able to get some sleep!

10.5mm digital fisheye, 75 exposures stacked together in Photoshop, each exposure 4 minutes at f/4 and ISO 400, for a total exposure time of about five hours, tripod mounted

In landscape photography seasons matter—a very great deal! When I am planning a trip, or on location shooting, one of the first things I think about is the season. Some of my considerations are pretty obvious: in winter there is snow on the ground, in spring flowers are in bloom, and in autumn there are fallen, colorful leaves. But the importance of seasonality to landscape photography goes beyond the obvious, and is a crucial aspect of the sense of place that is palpable in superior landscape photographs.

Landscape photography does not exist in a vacuum. In fact, our response to a landscape image is inextricably bound up with how well that photo speaks to our sense of place. A landscape photo that doesn't have a strong sense of place is banal. This kind of wishy-washy image may work in a stock photo that is intended for generic usage, but it will not be the kind of photo that has emotional resonance.

There are many different kinds of places that can provide specificity to a landscape photo: intimate views, grand landscapes, mountains and oceans, jungles and deserts. In all of these kinds of landscapes, the season plays an important role in convincing the viewer that what they are seeing depicts an actual place at a specific time.

Somewhat paradoxically, while the best landscape photos do have specificity, they also have an emotional resonance that goes beyond the specific—and heads towards a Platonic ideal of the subject matter. Great images of majestic mountains remind us of the way mountains should be, if only we could be in the right place at the right season!

- Spring wildflowers make the coast of California beautiful beyond compare; the scene shown here with its carpet of yellow blossoms and a rugged coastline is at the western tip of the Point Reyes peninsula.

18mm, 1/160 of a second at f/11 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

Beyond the flowers-in-spring, snow-in-winter aspect of seasonality in landscapes, there are many more subtle ways in which the season is important to the landscape photographer.

An overlooked aspect of seasonality is the way it impacts lighting in landscape photos. The angle of the sun is different in different seasons. For example, in winter, lighting comes from a low angle, and if there are no clouds, it is harsher than at other times of year.

The time of year affects where the sun and moon rise and set on the horizon, and also how early or late this happens—with the changes in this geometry being of greater magnitude the further one is from the equator.

If you are shooting early in the morning or late in the afternoon—as is so often the case with landscape photography—the time of year impacts not only sun and moon and overall quality of light, but also the other astronomical bodies that you may be able to capture during twilight.

As a practical matter, I make careful note of the season when I am going on location with three points in mind:

- Are there special features of the landscape I should be looking for, e.g., spring flowers, snow, or autumn leaves?

- How does the season impact the quality of light?

- Will my days be short or long, and how does the season change the length of the process of the sun setting (or rising)?

You might not expect it to be true, but it is: some kinds of photography are actually easier when the days are shorter. For example, I don't have to wait up so late to begin my night photography! In addition, it is often the case that cold weather in winter and early spring can produce atmospheric conditions of huge clarity.

- At high altitude near Whitney Portal, California, in mid-October the signs of autumn were all around me. I composed this image of Lone Pine Creek to emphasize the fallen leaves in the foreground, so the seasonality of the photo is very clear.

18mm, circular polarizer, six exposures from 1/2 of a second to 8 seconds (exposures combined in Photoshop), each exposure at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Pages 152–153: It doesn't often snow in the coastal ranges of California. So when this dramatic winter snow storm dusted these low mountains I knew I had to take advantage of the weather. No one could see this scene without realizing that it was taken in winter.

200mm, 1/620 of a second at f/13 and ISO 200, hand held

Earth and Sky

We call them “landscapes”—but many of the best landscape photos don't have much “land” in them. Water and sky are as important to landscape as the ground.

After all, we've long since internalized the concept that our world is more than a flat plane. We know that the earth is a round globe traveling through space. It's intriguing to picture the landscape in the context of the sky: clouds, and how they relate to earth-bound formations, the heavens, and the majesty of the stars as they gyrate through the night.

Even when a landscape photo is restricted in subject matter to “terra firma,” the viewpoint of exciting photos tends to be unusual or offbeat. After all, there's nothing very interesting to most people in a mundane landscape that they see every day.

To find unusual viewpoints—which amounts to a threshold bar that you need to cross to create exciting landscape photos—you can include unusual atmospheric or weather conditions in your photo, or include the context of the earth as a spherical object, or point your camera straight at the earth, but from a novel angle.

For example, most people don't usually see the landscape straight down in an aerial view from above. Aerial photography turns normal landscapes into vast patterns that could be macro shots until you understand the scale of what you are looking at.

More in the realm of everyday landscape photography, both wide angle and telephoto lenses can transform mundane reality by changing the apparent rules of perspective. In the hands of someone who knows their optics, you can look at a landscape photo and see places in entirely new ways.

I am always cognizant that the most interesting aspect of many landscape photos is what they say about the relationship of the earth and sky—either in the direct portrayal in the image or when you stop and think about what you are seeing. With this in mind, when taking landscape photos I try to:

- Emphasize the role of the sky as an equal partner with the earth in my composition.

- Choose my angle of view carefully to reveal visual aspects of the landscape composition that are not obvious at first glance.

- Select my choice of lens and focal length with the impact upon the landscape image in mind (see pages 82–93 for more about lens choice).

- Hiking around the circumference of Mount Tamalpais, California, the sea of clouds made me feel as if I were the last person left alive in the world. In the distance, Mount Diablo rose above the clouds, the only landmark poking through the vast cover blanketing San Francisco Bay.

48mm, 1/160 of a second at f/6.3 and ISO 100, hand held

- From the open window of a small airplane, I shot straight down at the earth covered with snow in the Alaskan winter; the river shown here was completely frozen, with the bend in the river and island making a neat abstract pattern. You don't really know it is a landscape until you look at it for a while.

35mm, 1/640 of a second at f/5.6, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 64 slide and converted digitally to monochromatic, tripod mounted

Pages 158–159: Surrounded by the magnificent rock formations of Valley of Fire State Park in Nevada, I set my camera up for the night, and pointed it north. As the night wore on, I became increasingly concerned about the light pollution from the city of Las Vegas, airplane travel to and from McCarran airport, and the increasing cloud cover. However, when I processed the image I was pleased to find that these worrisome elements actually seemed to add to the composition.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 129 stacked exposures, each exposure 4 minutes at f/2.8 and ISO 400, for a total exposure time of eight hours and 36 minutes, tripod mounted

Mountains

Mountains are where the earth meets the sky, and are thus a special place in the hearts of landscape photographers and those who love the wilderness. There's no doubt that some of the most dramatic landscapes are in the mountains.

However, the wilderness landscape of the mountains is often not hospitable terrain. Even though the alpine meadows in The Sound of Music seem placid, truly mountainous terrain is rugged and snowbound and shows the cataclysmic and tortuous gyrations of the earth when looked at from a geologic time perspective.

Complex landscapes of upthrust igneous rock combined with glaciated areas and vast fields of snow may be interesting to geologists who study the bones of the earth, but these elements will mostly seem a jumble to viewers of a photograph unless there is an organizing principle in the composition.

The high mountains, particularly in wilderness areas, are one of my favorite places to be—but I recognize that these rugged and remote areas are not everyone's cup of landscape tea.

There's also the question of how you get to these places while carrying camera gear. Sometimes you can fly over mountains to get photos, but most often this is an arduous labor of love performed on foot.

- Banner Peak, in the heart of the Ansel Adams Wilderness area in the Sierra in California, glows with the last light of the setting sun. As the season progresses, this vista will change, and a lake dotted with islands—aptly named Thousand Island Lake—will be revealed.

Trekking through the mountains to a location even as relatively benign as Mount Banner is often an arduous affair. To get to the spot where I snapped this photo I forded rushing creeks, climbed a snow bridge over a waterfall far below, and crossed over miles of snow fields. Later in the season it would have been much easier, as the area is crossed by the John Muir Trail, sometimes derisively referred to by the hardcore as “The John Muir Superhighway.”

38mm, 1/640 of a second at f/11 and ISO 200, hand held

I try to convey my love of mountains and the wilderness in my landscape compositions using these strategies:

- Showing an interesting sky along with the mountainous earth

- Using the foreground to capture an element such as a flower that helps humanize the scale of the scenery

- Capturing mountains from a distance to allow the viewer to get a sense of a greater formation

- Trying to create a “symphonic” presentation, so the grandeur of the mountains prevails over the apparent chaos; for example, from a distance, a glacier can seem to be a kind of “highway”

- Dawn strikes Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the continental United States, from the east, leaving the lower elevations still in deep shadow.

70mm, 1/20 of a second at f/4.5 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

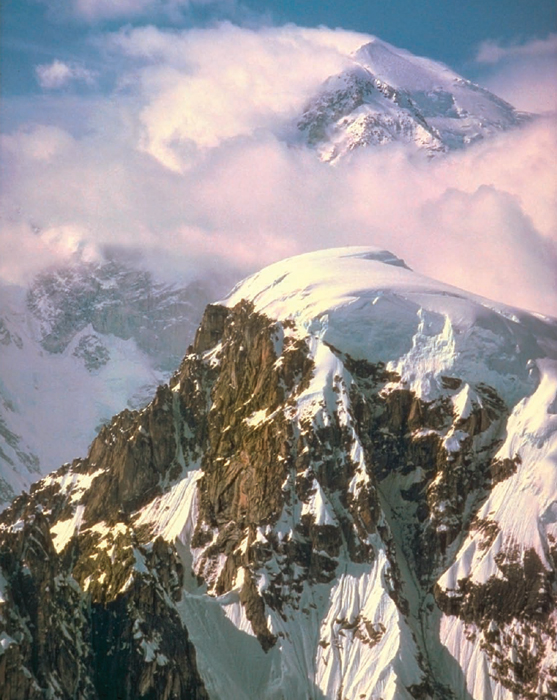

- This aerial photo shows a formation known as the Mooses Tooth in the foreground, with Denali behind it. (The official designation omits the apostrophe from Mooses Tooth.) I was leaning out the window of a small plane to take this photo. The pilot didn't seem very confident—he kept telling me about the bad air currents around Denali and that he hadn't done too much of this kind of flying before. I tried to ignore his running commentary while I concentrated on the symphonic landscape around me.

85mm, 1/1000 of a second at f/4, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 64 slide, hand held

- This is a shot of Ruth Glacier, one of the many glaciers that form an interlocking system around Denali in Alaska.

Leaning out of a small plane, with the wind whistling past me, looking down at this magnificent highway of ice and rock, I felt as if heroic music was playing all around me. The pattern of the glacial highway seemed to go on forever—and indeed Ruth Glacier does extend many miles in length.

Of course, when I shot this photo (in the 1980s) we did think the glaciers would go on forever, and had no concept of global warming. I'm sure a contemporary photo would reveal a glacier that has shrunk considerably.

35mm, 1/300 of a second at f/5.6, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 64 slide, hand held

Deserts

No topography is more barren, and no landscape more extreme, than the desert. Nonetheless, deserts are very fertile grounds for landscape photographers—because of their extreme and stark nature.

Perhaps more than in any other kind of landscape photography, you need to be properly prepared for desert photography. In the summer, this means protecting yourself from the heat, bringing plenty of water, and being extremely careful about navigation and topography. And in the winter, particularly at elevations above 5,000 feet, desert terrain can be astoundingly cold.

So my first rule of desert photography is to avoid summer heat and mid-winter chill. The best times of year for desert photography are spring and fall. In North America, I'd say late February through mid-May, and mid-September through mid-November, depending on exactly where you are planning to photograph.

No matter when I go to the desert, I take care to protect my photographic gear from extremes of weather, and from dust and sand.

Besides picking a time of year in which the weather is relatively temperate, here are some of the things I look for when I am going on location to photograph the desert:

- This high desert, sage brush environment is made visually interesting because of the patterned dusting with snow. In desert at elevated altitudes, it is not unusual to see snow in the winter months despite the overall lack of precipitation because days and nights are bitterly cold—so what snow there is lingers a long time depending upon patterns of sun and wind.

130mm, 1/500 of a second at f/11 and ISO 200, hand held

- Pages 168–169: Storms in very dry environments provide an opportunity for exciting photos—so my advice is to get ready for photography when you see inclement weather brewing near arid terrain. It was clear to me the minute I sniffed the ozone and saw the cloud cover that rainbows were likely, so I was ready for them with a polarizing filter mounted on my lens to enhance the saturation of the colors in the rainbow.

42mm, circular polarizer, 1/160 of a second at f/6.3 and ISO 200, hand held

- Weather conditions that are varied; the desert landscape is often most interesting before, during, and after storms

- Textures and patterns, writ both large and small; for example, the details in the patterns of shadows on a sand dune (small) or the contrast between snow and sage brushes on a distant desert mountain side

- Locations that provide foreground interest so that my landscapes can bring the viewer in to a larger landscape, but also find some relief from the vast, empty spaces of the desert

- I shot this image of late afternoon shadows in Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park in Utah near the Arizona border. Carrying photo equipment into sand dunes can be tricky, because sand is dangerous to cameras. However, sand dunes often are places where one can find very interesting patterns, particularly in the early morning or late afternoon.

105mm macro, 1/25 of a second at f/32 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Visiting Great Sand Dunes National Park in Colorado in late spring, I was struck by how the wind had “combed” the sand into neat lines of waves. Trudging over a sand dune I saw some flowers holding their own against the sand and wind, and knew I had to make an image.

105mm, 1/30 of a second at f/22, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 64 slide, tripod mounted

Seascapes

As long as there have been artists capturing the landscape their images have included the ocean. In times gone by the world's commerce travelled by water, navies ruled the world, and whales furnished the fuel people read by. The experience of shipwreck was common—everyone knew someone who had been wrecked. So the awesome force of the ocean was terrifying, and a proxy for all those majestic forces of nature that were beyond one's control. No wonder the ocean was such an important subject for so much art!

In today's world, the ocean no longer plays quite as crucial a role in the connectivity of peoples and commerce. However, it remains a great subject for photographers and other artists.

Always changing, never the same twice, calm or dramatic, a seascape is the canvas upon which the landscape photographer can practice his or her mastery of fundamental composition.

When I go on location to photograph seascapes:

- I check tide tables and weather forecasts so I can accurately assess what conditions are likely to be

- I never turn my back to the ocean, and always put safety first; it is never worth taking chances in order to get a photo, and it doesn't pay to underestimate the power of the ocean

- I shot this image from a bluff above Drakes Beach, in Point Reyes National Seashore, California. Drakes Bay can produce interesting waves because the prevailing wind direction opposes the direction of the surf—an effect you can see here in the middle line of waves which is actually headed outwards towards the topmost wave.

105mm, circular polarizer, 1/160 of a second at f/7.1 and ISO 100, hand held

- Heavy surf warnings were in the news. Hard rain was driving pounded surf into the storm-bound shore of the Northern California coastline. I carefully pulled my telephoto lens out, trying to shelter my equipment from the weather, and snapped this photo from a coast observation point, then quickly got the expensive piece of glass back into its protective bag.

200mm, 1/620 of a second at f/2.8 and ISO 200, hand held

- I shot this image from a bluff above Drakes Beach, in Point Reyes National Seashore, California. Drakes Bay can produce interesting waves because the prevailing wind direction opposes the direction of the surf—an effect you can see here in the middle line of waves which is actually headed outwards towards the topmost wave.

- I'm aware that the sea spray and sandy beaches can represent an extreme hazard to photographic gear

- I pack a polarizing filter near the top of my bag

- I look for patterns and shapes that exemplify the fundamental nature of waves as a building block for light, sound, and many other forces in the universe

At low tide, there are interesting ponds and shallows to photograph in the intertidal zone. At high tide, or when the tide is coming in, the surf is at its most ferocious and elemental. Let's face it: waves are always exciting to photograph, and including a rugged coastline can only enhance a landscape image.

- This image of the Tomales Point fork of Point Reyes, California is a good illustration of a seascape that manages to capture the feeling of the curvature of the earth. In other words, looking at this landscape it is not hard to feel that the world is indeed round because of the curved horizon lines on both the land and water.

18mm, 1/4 of a second at f/13 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

People and Landscapes

- Leaning over the edge of the parapet of the new Hoover Dam Bypass Bridge, I used my fisheye lens to shoot a vertigo-inducing view of the Hoover Dam. I was particularly interested to include the shadow of the bridge itself as an important element of the composition.

By the way, a little research shows that in addition to his great landscapes, Ansel Adams enjoyed making heroic images of important feats of engineering such as this very Hoover Dam.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 1/500 of a second at f/11 and ISO 200, hand held

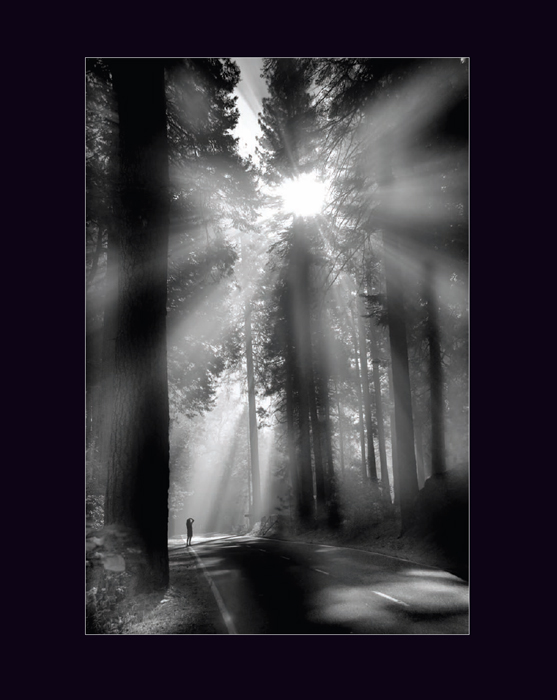

- Following a rock slide in Yosemite Valley, crepuscular rays from the morning created fascinating lighting effects among the redwood trees on the valley floor. I shot many variations on this image, but the one with the fellow photographer in it seemed to give a sense of scale to the trees—and it works better for me as an image than the version without people.

32mm, 1/400 of a second at f/5 and ISO 100, hand held

The truth is, it isn't so easy anymore to find a landscape that doesn't have people, or at least some traces of people in it. I've been there, in Alaska, in the high Sierra, and in other remote places—but you really have to work to find places that appear pristine, without any sign that people have been there.

If you don't believe me, look around carefully next time you are in the wilderness. Then wait for nightfall—if you didn't find evidence of civilization during the day, you will almost certainly see airplanes and satellites at night.

It isn't really clear that landscapes without people are such a good thing. The truth is that having people or their works in a landscape photo can greatly add to the interest of the image.

There are many kinds of landscape photos that involve buildings and people. City photography is one obvious example (see pages 186–189). But you also wouldn't think to photograph a landscape with quaint castles and ancient towns—such as you find in parts of Europe—without including these structures in some of your photos. Another kind of landscape with people creates compositions that contrast the beauty of the human form with the beauty of the natural landscape, to create images that may be more beautiful than either alone.

My recommendation is to be open minded about the definition of “landscape.” There are many things you might not think to photograph if you take a purist's view of landscape photography that are actually quite visually interesting. Furthermore, in many contexts the addition of a figure, town, or human artifact can really give a sense of scale to your landscape.

As a landscape photographer, it is fun for me to play with the difference that people have made. In some landscapes, not so much—but if you are photographing the Hoover Dam (page 176), the difference people have made is huge! It would take more than Photoshop to show this portion of the Colorado River without people (see pages 180–181 for an example of restoring a landscape to its pristine state using Photoshop).

- In this view of shadows and rock formations in the Pariah Wilderness on the Utah-Arizona border, my shadow gives the landscape a sense of scale.

I sometimes like to add a small self-portrait cloaked as a shadow, or hidden in a reflection, to my landscape imagery—as a way of saying “I was there!”

18mm, 1/80 of a second at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

It's hard to photograph in a place like Yosemite Valley without getting visitors in your shots, particularly on a sunny day late in spring.

- The original version of this photo shows the observation area next to the top of Vernal Falls on a fine spring day. There are folks walking around, looking at the scenery and taking pictures. A fence keeps them safe, away from the raging torrent.

- I decided that it would really be interesting to see this landscape vista without people, the way a Native American five hundred years ago might have viewed it. Voilà, a couple of mouse clicks later—and Photoshop has changed the world! The people and the fence are all gone. Now, there's nothing to stop me from standing at the very brink of Vernal Falls to make my photo, as I've often wanted to do.

Both: 25mm, 1/200 of a second at f/10 and ISO 200, hand held

Reflections

Reflections are one of my favorite things to photograph. Including a reflection in a landscape automatically increases the interest of the resulting photo, so locating sources of reflectivity—usually water in landscapes—that can be organically integrated into your landscape compositions should be a top priority.

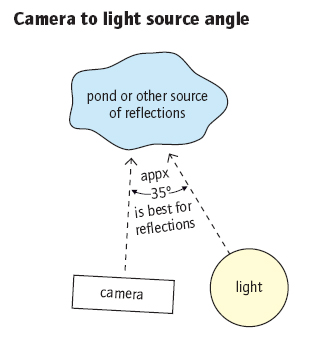

The best reflections occur when the predominant light source is not too harsh, for example, towards the end of the day. Ideally, for the best reflections, light should be coming from above and behind the camera, and to the left or the right. In this scenario, if you drew a line from the camera to the reflection, and a line from the light source to the reflection, the camera to light source angle would be about 35 degrees (see the diagram below).

Once you've located a body of water that is reflecting, there's an issue as to whether the water is in motion. If the water is moving, the reflections may not be as high quality as if the water is still. In addition, you may need to use a fast shutter speed to stop the motion of the water (see pages 118–123). Depending on the specific situation, this may mean you don't have sufficient depth-of-field for a given composition (see pages 106–113 for more about aperture and depth-of-field). The conclusion to be drawn from this is that still waters not only run deep, they are also best for photography!

- The colors in this reflection in Lake Tenaya in the Sierras of California seem more vivid than the “real-life” counterparts on the lake shore.

18mm, circular polarizer, 1/60 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

I almost invariably find that using a polarizing filter can improve the vividness and saturation of reflections—and this is one of the few filters that works better on your camera than when applied after the fact in the digital darkroom. In fact, there is almost no practical way to recreate the impact of a polarizer in post-processing, so plan to use one in the field in situations where it enhances the image.

- I came across this still pond while wandering on snow shoes in Yosemite Valley, California in the winter, and immediately decided that the reflections made the scene look like a wintery poem. The intricate patterns of a snow-covered tree are neatly caught and reflected in a pond, while the whole composition is “framed” on the left and right by out-of-focus trees.

170mm, 1/400 of a second at f/10 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- Wandering in downtown Oakland, California, with my camera, I happened to look across the canyon of “Broadway” and noticed these reflections in the windows of the office story on the other side.

200mm, circular polarizer, 1/250 of a second at f/7.1 and ISO 500, hand held

The City as Landscape

- I shot this view of Manhattan looking downtown towards the Empire State Building and the World Trade Towers from the deck of the Rockefeller observatory in the 1980s.

20mm, 2 seconds at f/16, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 25 slide, tripod mounted

- Hanging out of the door of a helicopter, with only a tethered harness to keep me from falling straight down, it almost seemed like I could touch the antenna on top of the World Trade Towers, but actually I was about 500 feet above the tops of the buildings.

Every time I look at my photos of the World Trade Towers, I feel quite sad because the day these buildings were destroyed by terrorists was a terrible day for humanity.

But at the same time, I'm glad to have these photos as a record of how things were—and also to assert once and for all the emotional importance of landscape photography.

50mm, 1/640 of a second at f/4, scanned from a 35mm Kodachrome 64 slide, tripod mounted

I know that you're going to look at me as though I'm kind of weird when I say that I enjoy shooting cities as landscapes. (Well, you already know that I love shooting cities if you've gotten this far through my book!) In this kind of photography, basically you ignore people. You pretend they aren't there.

Treating cities as landscapes takes a bit of imagination. Maybe some kind of super apocalyptic event has made all the people vanish, leaving the buildings intact (I certainly hope this never happens, of course!). This leaves the hills and mountains (the man-made buildings) and the canyons and valleys between the buildings (major boulevards are valleys, and deep narrow streets are canyons).

When photographing a city as this kind of landscape, I need to understand its topography, just as I would in the real mountains. Where are the high places that one can shoot down for a bird's eye view? What is the best position to photograph the massifs and towers that rise from the “plains” of smaller buildings?

Taking this one step further, just as with natural formations, planning tools can help to understand the lighting at specific times of day, as well as any special phenomenon that might make for a good photo. For example, it's interesting to plan a location session around moonrise or moonset behind a well-known landmark. See page 144 for more information about some of the planning tools I use.

Boiling what I've said down to basics, my first step when photographing a new city as landscape is planning. I learn about the history of the place before I visit, and I spend a great deal of time studying the best maps I can find. Next, I try to identify the following kinds of places in the city:

- Those that will work for bird's eye vistas from above

- Spots that give panoramic views of the skyline

- Interesting structures that will work well at sunrise, sunset, moonrise, or moonset

Of course, the best news for the photographer who treats a city as landscape is that unlike a real wilderness landscape assignment there's never any reason to go hungry, or to skip your lattes!

- I selected my location and planned this shot based on information gleaned from The Photographer's Ephemeris (see page 144 for more about TPE) about when the full moon would rise over San Francisco's Transamerica towers.

400mm, 2 combined exposures at 1/30 of a second and 1/2 of a second, each exposure at f/5.6 and ISO 400, tripod mounted

The Night Landscape

Night blankets the earth half the time, so it makes sense that landscape photographers should consider expanding their horizons to include the dark side. This particularly makes sense when you consider the drama inherent in lights at night—whether those lights come from stars or city streets. When the world is otherwise in darkness, vivid colors can seem all the more spectacular.

Generally, when I am photographing landscapes at night, I look for vistas where there is interest in both foreground and background. Background interest can come from star circles, but to maximize them (at least in the northern hemisphere) you do need to point your camera north.

Landscape exposures away from cities at night are long affairs—very long. In normal photography, you think of a shutter duration of more than 30 seconds as long. In night landscape photography, it is not uncommon to have total exposure time be in the hours.

While these images are often composites—because combining images in the digital darkroom using a technique called stacking cuts down on noise compared to a single exposure—the total exposure time is often in the hours.

This means that you may be able to take only one landscape photo per night. Therefore, it's wise to scout night photography landscapes when it is still light. This not only cuts down on the risks inherent in night photography, it also means that you are more likely to be able to orient your composition the way you want, and to frame it nicely.

- During a night photography workshop I led, the class photographed Bixby Bridge along the Big Sur coast of California. I think this photo humorously makes clear the very real hazards involved in night photography—although I haven't lost anyone in a workshop yet!

10.5mm digital fisheye, 3 minutes at f/4 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- Pages 192–193: This is a composite shot taken in the middle of the night in the Alabama Hills region of eastern California. The camera is pointing due north, as one can tell by the relatively stationary position of the north star in the center of the star circles.

In combination with the dramatic star circles in the sky, the unusual rock formations in the foreground create an otherworldly effect, almost as if this landscape had been shot on another planet.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 27 exposures, each exposure 4 minutes at f/2.8 and ISO 400, for a total exposure time of 108 minutes, images combined in Photoshop using stacking, tripod mounted