The Tao of Landscape

Why Landscape Photography

Tao (![]() , sometimes transliterated “Dao”), is a philosophy with ancient roots that refers to the primordial essence of things, the natural order of existence, and the fundamental aspects of the universe. Traditionally, it is difficult to define Tao or to express it in words, but it is possible to know Tao, and to feel it—and, when the force is with one, to express Tao in art.

, sometimes transliterated “Dao”), is a philosophy with ancient roots that refers to the primordial essence of things, the natural order of existence, and the fundamental aspects of the universe. Traditionally, it is difficult to define Tao or to express it in words, but it is possible to know Tao, and to feel it—and, when the force is with one, to express Tao in art.

One kind of art that has traditionally concerned itself with Tao is Chinese landscape painting, which was often practiced as a spiritual exercise. Mountains and wild scenery were very important in these landscape paintings, and symbolized closeness to raw nature, as well as embodying a source of spiritual energy and life.

This mystical sense of being in-synch with nature is a vital part of what landscape photography means to me, and why this kind of photography is so important to me.

In a similar and related way, my trips to the wilderness have the same benefit. When I begin my journey into the wilderness, often trekking into an unfamiliar environment and encountering dangers that are very different from those found in a city, I am weary of the hypocrisy and excesses of so-called civilization. By the time I am leaving the wilderness, I am refreshed and renewed, with a sense of purpose and oneness with nature, and the perspective to undertake the challenges that face me in life.

Of course, not all landscape photography takes the wilderness as its subject matter. For that matter, not all landscape photographs are intended to be “beautiful” or large in scale. Photographs on a microscopic scale, images of the polluted environment, and the New Topographics Robert Adams-style shots of banal subdivisions and housing projects captured neutrally are just as much landscape photos as are the grand Ansel Adams set pieces of pristine monochromatic nature.

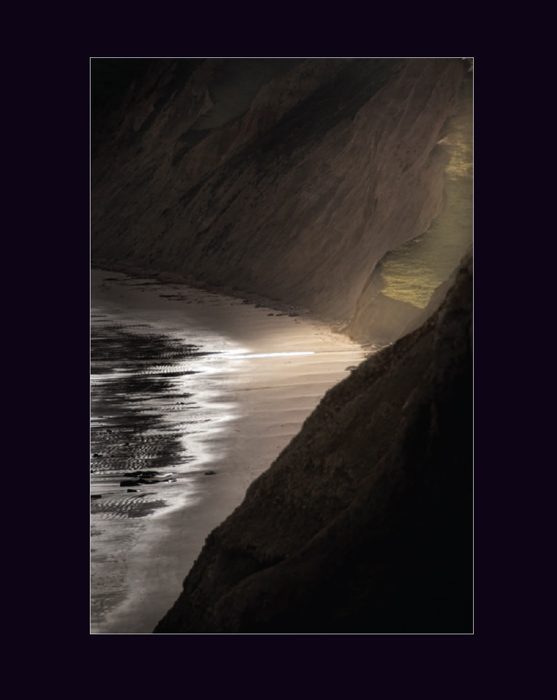

- Without darkness there is no light, and when things are darkest, distant light seems brighter. Metaphor and solace, perhaps, for troubled times—or at least my meditation on this “grab shot” from the bluffs above Drakes Bay in Point Reyes California.

One doesn't often think of landscape photography as requiring good reflexes and split-second timing, but sometimes it does, and this image is a case in point. Sunlight, filtered through a gap in the clouds, illuminated the cleft only very briefly. Blink and it was gone.

I underexposed by about two f-stops compared to an average light reading to increase the contrast between the dark cliffs and the sunlight, and shot with a 200mm lens—the longest lens I had with me.

200mm, 1/640 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, hand held

- Pages 12–13: It's hard to believe that this lush landscape showing the foothills of the California Coastal Range with Mount Diablo behind was taken just a short way from downtown Oakland, California. In part, the magic of the scene is created by the morning mists and clouds—which were gone a few minutes after I snapped this photo. Also contributing to the effect is the ephemeral green lushness of the California hills in springtime. Both factors go to show how important timing is in landscape photography—a few minutes earlier or later, or at a different time of year, and this image would not have been possible.

120mm, 1/640 of a second at f/10 and ISO 200, hand held

Personally, I know which of these modes I'd prefer as my goal, although slavish imitation of something that has already been done is not to be desired.

Technique and craft are the strategies used to arrive at a goal. Before exploring the craft of landscape photography in the digital era, it is necessary to understand the Tao of landscape photography and its underlying goal—as well as understanding one's personal predilections in terms of genre and style.

- This is an image shot about an hour after sunset of the famous Wave rock formation in the Coyote Buttes area of the Paria Canyon/Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness along the Arizona-New Mexico border. Access is by permit only, is severely limited, and involves a hike over rough terrain.

Sunset comes early in the late autumn (when I shot this image), and the jumbled country around the Wave was very dark at night. Still, I figured I'd have no problem getting out the way I had come by the light of my headlamp. But in the darkness I lost my way. I ended up spending the night pacing in circles to keep warm, teeth chattering.

As the pale light of dawn began to illuminate things, I was glad I had stopped. Between impassable crags, a gorge and network of crevasses opened at my feet. I turned around, and began to make my way back down, coming shortly to the cairn-marked trail, which I had crossed without recognizing it in the night.

To photograph at sunset or after sunset in a remote location means getting back after dark—or spending the night. This is one place I'd gladly take the risk of a cold night if I get to photograph it again.

12mm, 30 minutes at f/11 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

That said, I do believe that the goal of all landscape photography is essentially the same—to reconnect with the Tao and magic of the world around us.

At its best, landscape photography should be conducted as a spiritual exercise related to finding ourselves and our place in the universe. An important part of this exercise is experiential—and great landscape photos result from the authentic feeling of being fully present, along with a mastery of the tools and craft of photography.

- Long before the sun was up, I headed west on an empty Nevada highway towards Death Valley National Park. The air was cool before dawn, and I drove with my windows down enjoying the breeze. I knew things would get hot soon enough.

At the Hells Gate entrance to Death Valley National Park, I took a cutoff past the Wonder Mine. A little above the Wonder Mine, I pulled off by the side of the road to photograph because I could see the first light of morning beginning to create a purple, layered effect in the foothills of the Funeral Mountains.

I waited, and as the sun came up, I snapped this photo. Then the sun rose a little higher, and the full heat of daytime in Death Valley was upon me.

300mm, 1/50 of a second at f/36 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- If you don't spend much time out in nature, you might think that the sun follows a simple routine, rising in the east and setting in the west. To some extent this is, of course, true—but if you note where on the western horizon the sun sets, you'll observe that the points where the sun sets track a great journey from north (in the summertime) to south (in the winter), and back again. (This statement is true in the northern hemisphere, and reversed in the southern hemisphere.) The further north you are, the greater the north-south journey on the horizon that the sun undertakes.

Don't worry if this sounds complicated—if you observe the setting sun over a few months, you'll get the idea. Modern planning tools can also help pinpoint your understanding of where you have to be in relationship to astronomical bodies to make specific images (see page 144).

My thought in capturing this image was—as you can see in the result—to position the setting sun between the two trunks in this split tree near where I live in the San Francisco Bay area. The trick, of course, was a matter of timing: the sun will set between the trunks only twice a year and there's only a split second in any given sunset in which the sun will be in the right position for a straight-on shot—and also, of course, the sunset should be spectacular as in this shot.

75mm, 1/250 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, hand held

- Pages 22–23: Slightly to the north of Badwater— the lowest point in North America at 282 feet below sea level—lies the so-called Devil's Golf Course. This is a formation of seemingly endless crystallized salt spires arranged, well, like a diabolical golf course.

As I considered how to make an interesting composition from the barren landscape that stretched seemingly without end, I realized that a fisheye lens made the horizon seem to be curved—in essence turning the flat plane of the Devil's Golf Course into what might be an alien world.

To add further to the apparent strangeness, I added the star burst effect to the sun by stopping my fisheye lens down to its minimum aperture, f/22.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 1/500 of a second at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

Landscape in the Modern World

In a world that is burgeoning with people, where global warming and global “weirding” have led to unpredictable climate cycles, where finding nature often implies a long and targeted journey rather than merely stepping out of one's front door, what does it mean to be a landscape photographer?

The reason I photograph the landscape in the first place is that this activity has to do with connecting to the Tao, the essential spirit, of the world around one (see pages 14–23). However, a more down-to-earth view of the role of the landscape photographer (so to speak) is certainly possible.

At its core, landscape photography is a genre that is used to show spaces within the world, ranging from the tiny to the vast. There's certainly a sense among some photographers that landscapes should be about capturing nature and showing vistas that are free of references to humanity. In addition, the best landscape photographs are often elegiac and appreciative of the scenery that is shown.

This romantic point of view essentially equates landscape photography and nature photography. How much sense does it make to be doctrinaire about this viewpoint? In the modern world, several of the assumptions about landscape photography that this viewpoint embodies are not universally valid. For starters, it's quite clear that it makes sense for some landscapes to include both structures and people (for more on landscapes with people see pages 176–181).

In fact, a modern view of landscape photography pretty much has to include some sense of people and their artifacts—even when the evidence of humanity is scant because visitors have truly followed the precept of “leaving nothing but footprints and taking nothing but photos.”

In a famous poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley, the great emperor Ozymandius has left a huge monument he thought would last forever, yet it has vanished under the vast and trackless sands. In the same way, much of what our generation of humanity builds upon the earth will eventually pass—in one way or another. But for the time being, the structures, marks, defilements, and attempts at beautification are very evident—and a proper subject for landscape photographers.

- In its time, Mare Island was the largest naval shipyard on the west coast of the United States with literally thousands of workers during the Second World War. Then Mare Island was abandoned, and the artifacts of activity became a kind of urban landscape in decay.

To make this shot of a gantry used to work on naval vessels, I picked a dramatic viewpoint so that the vanishing point seems to go on forever, with the mechanism echoed in the reflections in the rain puddles—much as one might seek to dramatize a view in the mountains with reflections and perspective.

24mm, 1/20 of a second at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

The best attitude one can have towards these extant structures is to embrace their transience. This means moving from Tao, where the landscape photographer spiritually begins, to Wabi-sabi (![]() ), a Japanese aesthetic and world view that accepts that everything passes, and is transient and incomplete. Art based on Wabi-sabi (as for example, the genre of urban exploration photography) accepts this decay and decline as beauty—and utilizes it as the prime vehicle for conveying emotion in imagery. All things pass, and in their passage lies beauty.

), a Japanese aesthetic and world view that accepts that everything passes, and is transient and incomplete. Art based on Wabi-sabi (as for example, the genre of urban exploration photography) accepts this decay and decline as beauty—and utilizes it as the prime vehicle for conveying emotion in imagery. All things pass, and in their passage lies beauty.

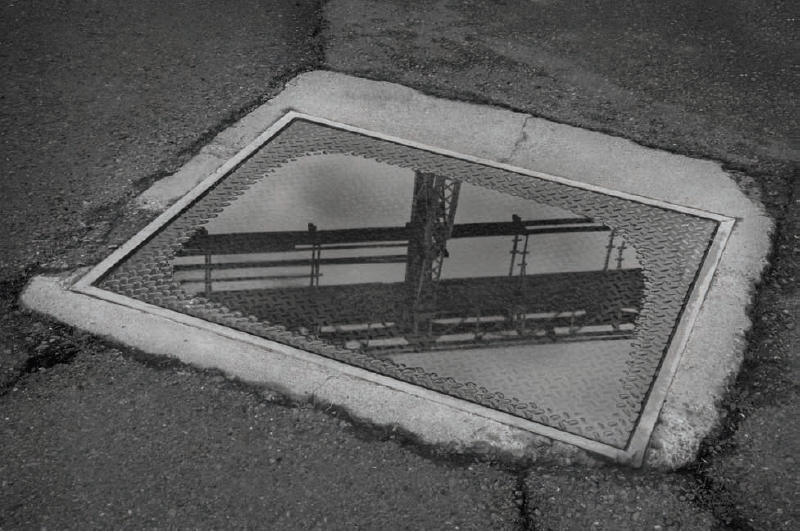

- In this shot, a puddle frames the distant landscape-like view of the gantry shown in the photo on page 25. The reflection is itself framed by a trap door that presumably leads to an underground passage, or world.

The point of this shot is the framing of the reflection—thereby fitting in with one of the traditions of landscape photography in which a frame internal to the photo is used to add compositional interest to distant elements.

36mm, 1 second at f/29 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- A digital infrared capture brought out the texture and colors in this abandoned dry dock. As you can see, the dry dock is several stories deep, and recent rains have emphasized the decayed look of the stone walls—almost like a natural landscape.

70mm, 1/100 of a second at f/5 and ISO 200, hand held (digital infrared capture)

- Coming into Las Vegas, Nevada after a week or so of photography and dusty camping, my two sons and I decided to opt for a luxury high-rise hotel. From our thirtieth-floor room, the clouds reflected in the mirrored windows of a facing building and made a nifty, almost abstract landscape—with the clouds and sky seeming to move across the face of the building against the strong horizontal lines of the architecture like musical notes on a staff. I used a polarizing filter and a wide open aperture (f/5) with low depth-of-field to help cut down the reflections in the window I was shooting through (it wouldn't open). The polarizer also helped to boost the saturation in the reflections that are the subject of the photo.

80mm, circular polarizer, 1/30 of a second at f/5 and ISO 200, hand held

- Pages 30–31: The landscape of San Francisco Bay is a great and wonderful panorama laid out for those of us lucky enough to live or visit there—yet so many people live their day-to-day lives without taking a moment to look at the elegant and wondrous vistas around them. Unlike many human structures, the Golden Gate Bridge adds to the visual beauty of the landscape.

This image shows the sunset at a time of year when the sun was setting at the midpoint of the bridge. I timed the exposure for almost the last possible moment when the ball of the sun was still visible—with the idea of creating an image that shows the Golden Gate Bridge almost compressing, or pressing down on, the sun.

250mm, 1/1250 of a second at f/13 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

Grand Landscapes

When discussing his photography in Yosemite Valley and the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Ansel Adams noted that he had “great opportunity to follow the light and the storms, hoping always to encounter exciting situations.” Adams wrote that he liked to keep moving as he made clear when quoting an Edward Weston quip: “If I wait for something here, I may lose something better over there.”

The grand, graphic, and lyrical landscape—even in the absence of people and their artifacts—is not, in fact, really about land. Weather and lighting are two crucial aspects of the landscape. Even mundane terrain becomes exciting if the weather or light—or both—are interesting enough. The most exciting landscape in the world is boring when the weather is placid and the light flat. Essentially and existentially, the weather and the lighting are more important than terrain.

- The Alabama Hills, below Mt. Whitney and the high crest of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, are a wonderfully jumbled area of rock formations and arches—a veritable maze of passageways and vistas that is often seen as a visual shorthand for the wilderness of the western United States. This is the area that was used as the background in so many of Hollywood's early westerns and films such as Gunga Din—around every corner there is an iconic formation of rocks that you might recognize from those late night reruns.

If this is the fabled wilderness of early Hollywood, John Wayne, and John Ford, then why all the traffic on the right side of the image? Actually, the lights are made by only a few cars—but this is definitely a different view of the famous landscape location, and one that took some planning to make. To create this image, I was in position on a high, rocky crag well before sunset. An establishing shot captured the immense vista with the details of the rocks, and then a long series of captures through the night recorded the movements of stars—and the few cars on the roads.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 25 captures stacked in Photoshop, each capture 4 minutes at f/3.2 and ISO 250, tripod mounted (total exposure time 1 hour and 40 minutes)

From the viewpoint of the photographer, the three secrets of landscape photography are location, location, location—where you plant your tripod and camera. Once they found the right spot for the image that they had pre-visualized, neither Ansel Adams nor Edward Weston hurried from location to location, even though the idea that the photograph may be greener over the next hill is always a constant anxiety in the field. The two other crucial elements—weather and light—come into play over time, or through repeat trips to a specific location.

The primordial experience of the landscape photographer is waiting—waiting for the weather, waiting for the light to be right, and maybe waiting for the sun, moon, and stars to be oriented in a specific location or direction. All good landscape photographers are good at waiting.

- For years, I had been keeping an eye on this old tree in a meadow in Yosemite Valley, California. Each trip I made to Yosemite I'd make a point of checking out the tree to see that it was still there, and to see whether the lighting was right. Finally, on this bright but snowy day in February, I made this image, contrasting the gaunt and nearly dead tree with the cloudy but luminous and sumptuous light surrounding Yosemite Falls. I processed the photo keeping the gauzy transparency of the day in mind—so the final effect intentionally looks almost as much like a watercolor painting as it does like a photo.

18mm, 1/250 of a second at f/11 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

One thing that makes landscape photography so interesting is the dichotomy between its apparent simplicity, and how difficult it actually is to do well. You'd think there is nothing simpler than finding a spectacular view, pointing some camera, any camera at it, using nominal or default automatic settings, and walking away with a grand landscape. Sometimes, although very rarely, this is indeed the case.

But the fact is that there is no wealth of great landscape photos. This is a discipline that requires planning and luck to be at the right place at the right time.

Often, considerable effort is required to get the photographer and equipment to the location. A sense of Tao is required to be spiritually connected to the landscape, and understanding Wabi-sabi is needed to love the landscape despite of—or because of—its imperfections.

Add to this the sense of Zen patience you'll need to let the light and weather unfold over time in the perfect way—and the challenge of this tough and frustrating genre is made abundantly clear.

- At the western-most end of the Point Reyes peninsula in California, the cliffs end abruptly in the endless swells of the Pacific Ocean. From an aerie above this rugged landscape, I photographed the lighthouse, ocean, and stars—using a combination of exposures long enough to soften the dramatic surf that always pounds this coast, and to create trails from the stars that were visible on this unusually clear night.

10.5mm digital fisheye, composite of foreground (10 minutes at f/2.8 and ISO 100) and sky (13 stacked exposures, each exposure at 4 minutes, f/4, and ISO 100), tripod mounted, total exposure time 62 minutes

- The redwood trees of California may be the tallest living things on earth, but the ancient bristlecone pines have the distinction of being the oldest. These gnarled specimens live at high altitude in the remote ranges of eastern California and Nevada, where life sustaining resources—water and nutrients—are in short supply. One of the secrets to the longevity of the species is the lack of competition in their high and dry eco-niche.

I photographed this bristlecone pine in the Patriarch Grove of the White Mountains in eastern California. I used an extreme wide angle lens (10.5mm digital fisheye) to capture the complex form of the tree as well as the dramatic clouds in the background.

10.5mm digital fisheye, 1/60 of a second at f/22 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- Pages 40–41: I climbed high on the East Mesa Trail in Zion National Park. If you look carefully, you can see the trail I came up as well as distant landmarks such as Angel's Landing, better known from below on the canyon floor. As the sun set, I took this photo, hoping to capture the landscape in its immensity and grandeur—and at the same time communicate the complexity of the system of rocks and side canyons which I had traversed on my trek to this location.

14mm, 2/5 of a second at f/22 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

Intimate Landscapes

At the opposite end of the scale from the grand landscape is the intimate landscape. Intimate landscapes can be tiny, but it's important to understand that they don't have to be. Like with grand landscapes, there's an almost infinite variety of subject matter possible.

Consider for a minute the phrase “Intimate landscape of,” and as an exercise think of how many ways you could complete the sentence. I think you'll see that there are a great many possibilities—and not all of them obvious until you spend a little time.

So intimate landscapes have as much variety of subject matter as larger landscapes. Lighting and positioning are still crucial—position of the camera in close-up shots is very, very sensitive—and waiting perhaps a little less so, depending upon the circumstances. But one key issue is establishing the visual intent to create a landscape.

- This image shows a “forest” of sea palms—a kind of kelp that grows in the intertidal zones. Each plant is a bit less than a foot high, so the scale of the entire composition is quite small—even though the viewer has no way of realizing this scale at first glance. My interest in the image was to create a vista that is essentially small in size, but that sucks the viewer in as though it was a grandly-scaled landscape. This dichotomy between the initial impression and a more thorough analysis creates an “Aha!”moment—and provides much of the interest in the image.

48mm, 45 exposures at shutter speeds from 1/6 of a second to 1/20 of a second, exposures combined in Photoshop, each exposure taken at f/29 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

A portrait of a flower is not a landscape unless there are some unusual circumstances, like a petal that seems to go onto the horizon line, or a burst of light within the flower that seems to echo a sunrise.

Bear in mind that scale and size are always relative. To an ant, a small bowl is the size of one of our houses—and if the ant were human, that human could probably not conceive of a structure as large as one of our houses.

The best photographs of intimate landscapes play on this ambiguity inherent in our appreciation of the size of things: the viewer looks at an image and thinks it is vast, or doesn't fully understand the scale. Further inspection reveals a close-up. Half the battle is won because you've intrigued, excited, and interested your audience by presenting something that may be everyday in an unusual way.

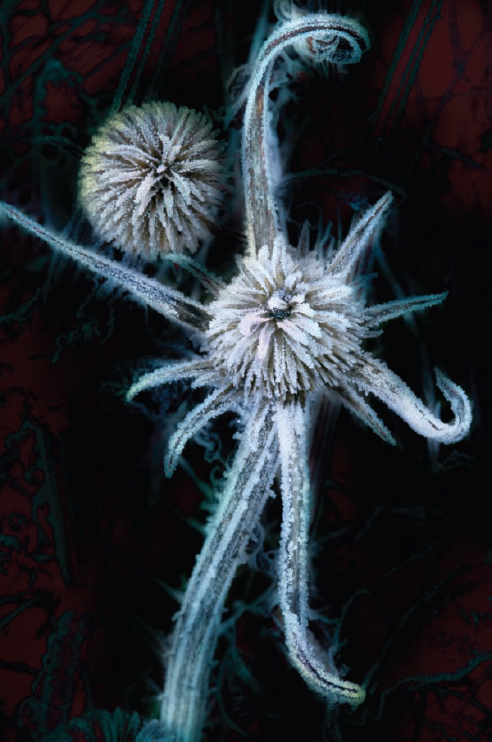

- This thistle is shown covered with frost—a rare phenomenon in the hills of coastal California. I underexposed the photo so that the hoary frost-covered plant emerges stark in contrast to an almost black background.

105mm macro, 1/4 of a second at f/36 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Alone at high altitude in the White Mountains of eastern California as the sun set, I focused on this intimate view of ancient bristlecone pines rather than the grander vistas that surrounded the scene (for examples, see pages 2–3 and 38–39).

The golden light was beautiful, and I was interested in the way the composition framed one gaunt and apparently lifeless specimen of bristlecone within another. Since the light was coming from behind my position, my biggest challenge was to make the photo without including my shadow, and that of my camera and tripod.

18mm, 1/15 of a second at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

Imaginary Landscapes

Does a landscape have to actually exist to be the basis of an interesting image? My answer is a resounding, “No.” Some of my favorite landscapes in art are imaginary—wholly or in part.

Of course, the ethics of photography depend on the situation and context, and how a photo is used and described. A journalist showing a landscape photo in a story that is about a forced migration, for example, has no right to substantially alter the landscape to make things look better (or worse).

But when I present a digital image as art, I am by definition making no claims about the authenticity of the image—in the sense that it may or may not correspond to any actual reality. In point of fact, there is really no way anyone else could capture even the “straight” landscapes that I create unless they were there at exactly the same time as me. These views have ceased to exist the moment after I have shot them, as light and weather changes.

Interestingly, even when there are a row of photographers shooting a landscape together—as sometimes happens—each photographer usually comes back with somewhat different results.

In any case, I take it as perfectly ethical and reasonable to improve the landscapes I've shot in the digital darkroom. Depending upon how you look at things, this is a sliding scale or a slippery slope!

No one will object when a landscape photographer increases contrast and tonality after the fact. This kind of minor adjustment is universally performed by serious photographers.

From there, it is a fairly short leap to improve composition by embedding portions of the landscape that was shot to make vistas seem to go on forever. Once you are compositing an image into itself, why not take it a step further and composite other images in to create a composition, or even add details by painting them in?

The sky is the limit once you accept the proposition that landscapes don't have to be real—and, in fact, that it may not be possible to create such a thing as a “real” landscape. When it comes to digital photographs of landscapes in the digital darkroom, the only real limit is your imagination.

- I love the view from Yosemite Valley, California when the weather gets foggy. My sense of awe and mystery increases because of what is not revealed as much as what I can see.

With this image, I post-processed the photo to increase a sense of partial revelation—and also to make the image look more like a Chinese ink landscape painting. Most of what you see in this image is “real”—my digital painting simply increased the fog in places and rendered the rock formations more firmly in others.

130mm, 1/250 of a second at f/6.3 and ISO 100, hand held

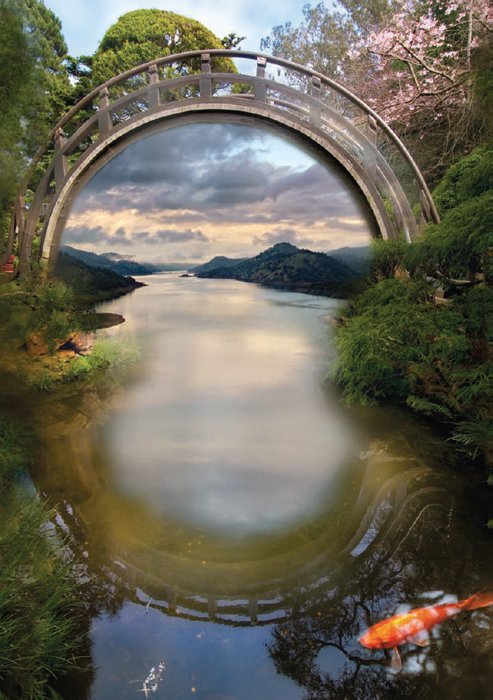

- This composite of three images shows a distant landscape opening through an ornamental bridge. The bridge is “actually” in the Hagiwara Tea Garden in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, and the landscape seen through the bridge was captured in the western Sierra foothills. The large, decorative koi swimming in the right foreground of the image is a third photo.

Putting these three photos together in Photoshop let me make a fantastic composition that I think of as a “portal”—the image invites the viewer to enter a different and magical land.

Bridge (Hagiwara Tea Garden): 14mm, 1/200 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, tripod mounted; Landscape (Don Pedro Reservoir): 20mm, 1/160 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, hand held; Fish: 70mm, circular polarizer, 1/100 of a second at f/5 and ISO 200, hand held

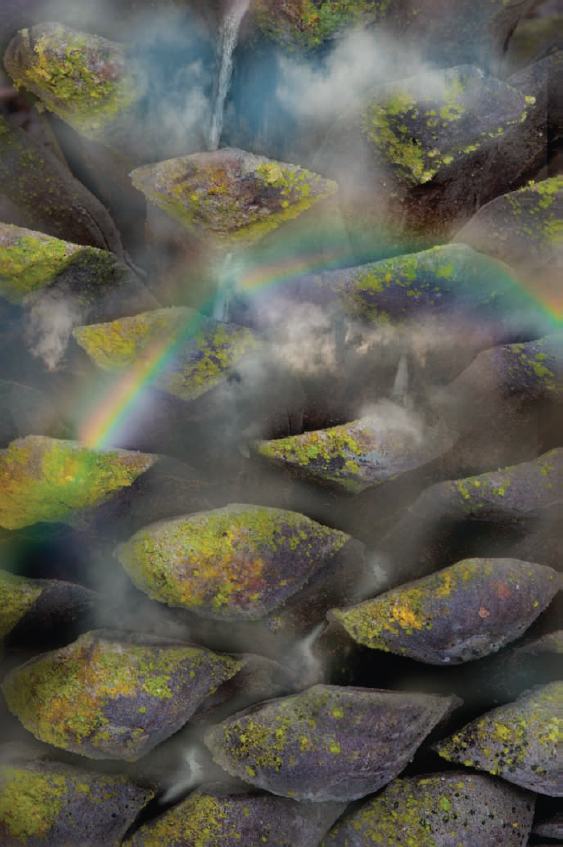

- This fantastic landscape is based on an original macro shot of a pine cone, taken on an evening walk on a coastal trail near the Golden Gate Bridge. Looking through my macro lens, it almost seemed to me like I was looking down on a mesa—my sense of scale got utterly lost, and I could see canyons and rivers. I exaggerated this effect by copying and pasting in several photos from my library and using digital painting to achieve the look I wanted.

105mm macro, 1.6 seconds at f/40 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Pages 50—51: The road beneath these windswept lines of trees seemed to go on forever. I exaggerated the effect by compositing successively smaller versions of the image into itself so the image seems to go on longer than it “actually” does.

40mm, 1/250 of a second at f/6.3 and ISO 200, hand held

Abstractions and Patterns

Some of the most interesting landscape photos that I've made work because they show patterns. By a pattern, I mean an overall composition with one or more recurring elements, although the elements that repeat can vary somewhat.

In landscape photography, the most interesting pattern compositions quickly take on an abstract look—observing the photo, the viewer is at first not quite sure whether they are seeing a grand landscape or something completely different, such as a textile, repeating tiles, or an ink painting.

An important aspect of patterned abstractions in nature is that they often convey a tactile sense of the subject matter. It's hard to look at a close-up of snow and ice crystals without thinking about how it would feel to handle the frozen structure.

Generally, an abstract landscape should begin by making the viewer guess about the scale of what they are seeing. Next, the fact that there is a repeating pattern should be conveyed in some way. Finally, a very real sense of texture should be conveyed.

An interesting landscape that lends itself to abstraction can be photographed to reveal many different possible permutations of the patterns that it conveys. It's often amazing how varied different views of the same patterned landscape can be. Sometimes it is worthwhile to present several related abstractions of the same landscape together—to show the different views of the same subject matter playing off each other (see example on pages 54–55).

The viewer should want to reach into the composition and handle what's there—and have strong feelings about the sensations that handling the subject matter would cause because of its textural nature, whether the photo shows an icy river bank or a distant, barren landscape that could never actually be “touched” in “real life.”

Everything comes to an end, as do all patterns. The best abstract and textural photos of landscapes convey a sense of pattern—but they also show the limits of that pattern. In other words, your photo of a pattern in landscape should convey the nature of the pattern, including repetition (if it's present in the composition). But the photo will be most interesting if the viewer can discover the limits to the pattern. The world without end is interesting, but the human eye is even more fascinated by boundary conditions.

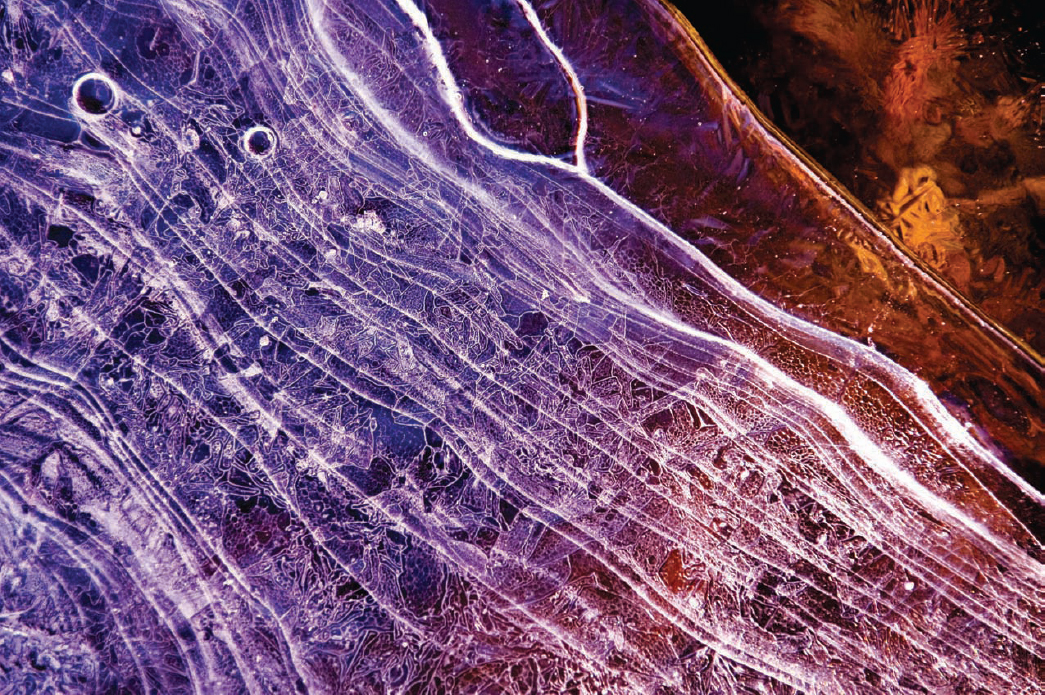

- I was exploring a grove of bristlecone pines high in the White Mountains of Eastern California. My thoughts were directed towards photos that showed entire trees, or even towards grand landscapes that included trees. But I had to stop and recalibrate my vision when I saw the patterns in this tree.

The patterns in the bark reminded me of the brush strokes of ink sumi-e landscape painting—so I shot the patterns on a macro scale rather than the tree as a whole.

105mm macro, 1/8 of a second at f/36 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- From Zabriskie Point, in Death Valley, California, the vistas spread out in magnificent variety. I find myself drawn to this spot, and have enjoyed photographing the views from Zabriskie Point over the years. I am most interested in views like this one that take the sun-baked hills and abstract them, so they are almost textural—and look like they could be a quilt.

56mm, 1/15 of a second at f/29 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- Top, right: This view from Zabriskie Point captures the ridge lines of the surrounding formations in profile—so they look like the folds in fabric if you didn't know it was a landscape.

70mm, 1/25 of a second at f/29 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- Bottom, right: A broader view from Zabriskie Point still gives a textural, abstract sense—as though one is looking at fabric, or a giant footprint rather than a landscape.

48mm, 1/80 of a second at f/11 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- On a foggy morning, I hiked a short distance to the beach. By the time I got to the ocean, the clouds were lifting and the sun was breaking through.

This was a day of fairly big surf, with interesting waves that moved irregularly and crashed with vigor. I decided to concentrate on the movement of the waves.

So that I didn't have to think about my camera settings, and so that I knew I could “stop” the motion of the waves, I boosted the ISO to 400, put the shutter speed to 1/2000 of a second, and used the exposure compensation control to underexpose by one f-stop (check your camera manual to see it if has this control, and how to use it). Putting the focus mode to manual, and focusing at infinity, meant I didn't need to worry about focus lag.

When the right wave came along, I was ready to catch it, backlit by the sun as it crashed on the steep shoals of the beach.

The result is an abstraction, poetry in motion: the viewer doesn't know exactly what they are looking at until they examine the image carefully—and may wonder where this photographer was standing to make the capture.

200mm, 1/2000 of a second at f/8 and ISO 400, hand held

- Along the banks of the Merced River in Yosemite Valley, California on an early spring morning, I noticed these interesting looking patterns in the skim ice, and stopped to make a photo using my macro lens. Depending on climate conditions, this kind of shot is usually best made early in the day before interesting ice formations melt away.

200mm, 1/100 of a second at f/5 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- This is an early morning view of a remote playa—or dried lake bed—in Death Valley, California. I shot the photo intentionally so that at a glance it is ambiguous about scale.

This is not a macro view; rather it starts angled close but continues the pattern created by the dried mud out to the horizon line. The harsh, directional lighting created by the rising sun adds to the sense of pattern—the viewer can tell the direction the light is coming from by looking at the shadows on the left side of the photo.

Close examination of these shadows also shows definitively that this is not a macro shot per se, and that the apparently repetitive patterns, almost like natural tiles, extend a great distance, but probably end on the left, where you can see the shadows, likely from a stand of vegetation.

31mm, 1/15 of a second at f/25 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

The Landscape in Black & White

Many of the photographs of the past that we regard as great landscapes—for example, the work of my hero Ansel Adams, or the photos of the great Edward Weston—are monochromatic. It's therefore natural to wonder whether we should be making landscape imagery in black and white—and also to consider what kinds of landscape images work best when they are rendered monochromatically.

My recommendation is to shoot digital RAW files that can later be converted in the digital darkroom to black and white. The advantages of RAW, and the mechanics of the many ways to go about converting a RAW file to monochrome, are extensively explained in my book Creative Black & White: Digital Photography Tips & Techniques (Wiley)—and if you are seriously interested in black and white, you should probably find a copy.

Since I am shooting RAW—which preserves all the information associated with an image file—I can decide later whether I want to present my photos as monochromatic or color images. I can even prepare two versions of the image, one in color and one black and white—and see which I like best.

However, to create great monochromatic landscapes it helps to think monochromatically in the first place. Some landscape subjects will work in black and white—and others need color. If you know you are planning to create a monochromatic image, you can choose your subject accordingly, frame it so it works best in monochrome, and expose for monochromatic processing.

- On the east side of the Sierras, the Alabama Hills extend for miles, a maze of jumbled rock, arches, and pinnacles framed in front of the crest of the high Sierra Nevada Mountains.

This is an early morning capture that uses monochrome to convey the harsh lighting contrasts shown in the landscape as the sun was rising (from the left of the photo).

52mm, 1/400 of a second at f/8 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

To create effective monochromatic landscape photos, you should look for:

- Compositions with extensive tonal range, where important portions of the image can viably be rendered as either black or white.

- Dramatic differences in the relationships between lights and darks in the image.

- Landscapes where the color in the image camouflages the underlying composition, and is not essential to the image.

Without color, compositional issues become far more important. In particular, you should pay attention to the way extremely dark areas relate to very bright areas to form the overall image. It often makes sense to underexpose or overexpose a monochromatic image to emphasize this compositional effect.

Before the advent of color photography, all photos were monochromatic. As time goes by, that era is receding into the dim past that memory can hardly recall. We see in color—so learning to see monochromatically requires affirmative (but worthwhile) effort. In the digital era, monochromatic imagery is not an anachronism but rather an intentionally mannered mode of reducing our landscapes to their stark and bare compositional essentials.

- To capture the sun coming through a break in the clouds during this wild and stormy day in the Alabama Hills, I underexposed by several f-stops. This allowed me to render the clouds as very, very dark while still showing detail and clarity in the foreground landscape.

20mm, 1/1600 of a second at f/20 and ISO 200, hand held

- A telephoto view (with a 150mm focal length) contrasts the foreground rock formations with the mountains shown in the background. This contrast helps make the mountains look otherworldly, and not quite real.

150mm, 1/400 of a second at f/10 and ISO 200, hand held

- Pages 64–65: On a cold winter's day, I wandered Yosemite Valley on snow shoes. When I reached the edge of the forest shown, and noticed the majestic cliff face towering above the trees, I was absolutely compelled to pull my tripod off my pack and shoot a series of images, of which this was the most interesting. Photography complete, I headed to the lodge for some hot chocolate by the fireplace.

27mm, 1/350 of a second at f/10 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- In this photo, the jagged edges of the dark shadows on the right contrast with the lines of the arid hills on the left to create an interesting landscape composition.

200mm, circular polarizer, 1/160 of a second at f/11 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

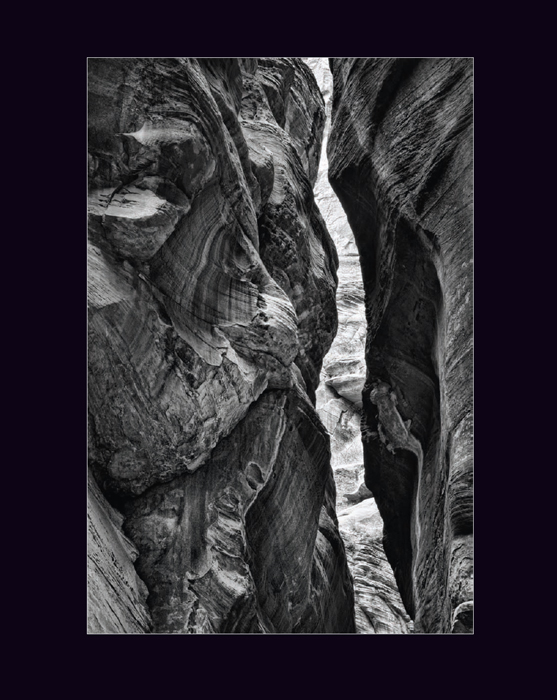

- Heading up the narrows of the Virgin River in Zion National Park, Utah, I was struck by the contrast of the narrow band of light coming through the slotted opening compared with the relative darkness of the rock walls around it. Rendering this contrast in monochrome seemed the purest way to convey my interest in this harmonious contrast between lights and darks.

75mm, 2 seconds at f/25 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Pages 68–69: On a foggy night in the Presidio in San Francisco, California, the street lights coming through the trees helped make a delicate and magical landscape out of what otherwise might have been a fairly mundane and normal view of trees in the city.

56mm, 52 seconds at f/4.8 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

The Lonely Road

In his poem “Ithaka,” C.P. Cavafy writes of the journey of Odysseus and that the real point of his voyage is experiential, and not about the destination; therefore, one should “pray that the road is long, full of adventure, full of knowledge.”

Photography is often about the journey, not the destination—and every journey starts with a road. J.R.R.Tolkein would have it that there is really only one Road (with a capital R): like a great river, it reaches every door step, and all paths are tributaries. In the words of his character Bilbo Baggins, “You step into the Road, and if you don't keep your feet there's no knowing where you might be swept off to.”

When I head out on a photography trip—whether it's an assignment or a self-assignment, whether there's only a loose goal in mind or the project is tightly defined—there's always a road. Even if my destination requires travel by foot or plane, it is pretty hard to get to a decent landscape without using a road. Then again, once you are on the road, as Tolkein reminds, you never know where it will take you. And as Cavafy's Odysseus learns, you are wise to take advantage of the unplanned stops. Some of my best photos have happened when I have let go of my idea about my destination, loosened up, and taken the time to look around me. It is true that serendipity happens, if you let it!

So roads figure largely in my landscape work—if not as the destination, then an important stop along the way.

I like to capture roads in all their endless, evocative variety—usually when they are almost empty at the beginning or the end of the day. If you look at my images and they make you think you can almost hear the wind whistling in the empty spaces of the landscape as a single car rushes by, then the photos have achieved the impact I am seeking.

Since roads will figure in any journey you make to a landscape destination, why not regard the road as an important part of your landscape photography?

- I had spent the night photographing star trails using an interval timer to create composite exposures of many hours duration. After finishing photographing the stars, I found a remote spot shortly before dawn where I could rest for a few hours. Early light woke me too soon, before sunrise. I drove down the road, stopping when I saw sunrise glinting on a few crags in a distant mountain range.

I parked the van beside the empty road and assembled my camera on my tripod. Placing the tripod in the center of the highway, I shot this photo of the first car of the day heading towards me in the cool of the morning before the sun came up harsh and strong.

If you want to try a shot like this, be careful about planting your tripod in the middle of the road (as I did here). You want to be sure that you have adequate visibility in both directions, and that no cars are coming.

200mm, 0.3 of a second at f/22 and ISO 200, tripod mounted

- This photo shows State Route 178 with the town of Inyokern, California in the background shortly after dawn. Inyokern, which lies about 50 miles to the northeast of Mojave, California, is a pretty hot, dry, dusty, and run-down place, notable for the presence of the Mojave green rattlesnake, a creature that combines the normal rattler pit venom with an advanced neurotoxin that paralyzes its victims. But in the oblique light of an autumn morning from above and beside the road, Inyokern looks positively glamorous.

48mm, 2 seconds at f/22 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- Pages 74–75: This is a shot showing the road near Tioga Pass, the highest car crossing of the High Sierra in California. To make this photo, I stopped at one of the first overlooks. The moon was brightly lighting the far side of the canyon, but where I stood the defile was in deep shadow. I waited for a car to start to climb the grade up to the pass, then exposed the image for two minutes—long enough for the car headlights to light the entire stretch of the road.

14mm, 2 minutes at f/5.6 and ISO 100, tripod mounted

- When I drive through Nevada, I am always struck by the wide open spaces and vastness of this country of basins and ranges. However, without eye-catching features the landscape can seem repetitive—and it can be hard to arrange a striking composition. Adding an empty road with its bold, striped yellow lines to contrast with the barren hills gives interest to the landscape as a whole.

70mm, 1/160 of a second at f/8 and ISO 200, hand held