What Global Leaders Should Know about Managing “Working Together at a Distance”

Over the past few decades, management theory has encouraged organizations to stride ahead, confident in the belief that leaders can be developed and shaped into a winning character, defying the widespread maxim that “Leaders are born, not made!” However, with the 21st century’s impetus of globalization, organizations have transformed the workplace into a boundaryless, innovative, and multicultural structure. This new phenomenon has forced organizations to create strategies that demand global leaders who are competent in managing virtual teams that thrive on diversity in many forms. Appropriate cross-cultural training needs to be developed and disseminated because the current workplace is composed not only of teams that are made up of heterogeneous members but also teams whose members are noncollocated and are strangers to one another. To recruit and retain talents who can shepherd a multicultural team to success in the virtual workplace may seem like a daunting task for a human resource manager. Instead, it may be more useful for a firm to train its own people as global leaders to prepare them for dealing with cross-cultural nuances and benefit from the synergies that are created by heterogeneous team members. In the context of global virtual teams (GVTs), then, the challenge is what strategies should a firm employ to nurture and develop global leaders who are culturally sensitive and competent to build and manage a high-performing GVT? Does it require diverse leadership characteristics, traits, values, and expectations?

Consider the culturally rooted challenges in the global virtual workplace that is illustrated in the scenario mentioned earlier in this section. What are the chances that such a situation could create conflict, frustration, confusion, and misunderstanding between multicultural, noncollocated team members? As a consequence of these difficulties, a company may find itself with demotivated and uncommitted employees. The reality is that, in many typical multinational corporations (MNCs), working at a distance is challenging and stressful, yet it can also be rewarding and exciting if handled properly. For instance, people no longer need to travel thousands of miles or suffer the turmoil and uncertainty of relocation and adjustment, while the company avoids the cost of cross-cultural counseling to prepare them for the expatriation process and the cultural shocks that they might encounter. The noncollocated workspace offers an innovative work structure in which many operating costs can be reduced or even eliminated. Similarly, many employees may find such opportunities deeply satisfying, since they can learn from and about diverse multicultural management and leadership styles.

On the other hand, cultural diversity poses heightened difficulties, and it can be a real challenge for people who have never had the opportunity to work in a GVT structure. Even those who have had GVT experience may still find it difficult to accomplish their goals due to inexperience in managing both the cultural and virtual aspects of this work structure. In each new heterogeneous team, leaders need to find unique ways to manage members and allow new ways of working to emerge out of different cultural values, attitudes, and practices. At the organizational level, the key questions for the human resource manager include the following: How can we recruit new talent and new executives who can fit into the GVT structure? How can we train and develop culturally competent global leaders who are able to deal with virtual teams that are composed of diverse cultural backgrounds? Does an employee have what it takes to work in a virtual work structure? How many will be willing to put up with these new challenges when their workload or responsibilities in their own office are competitive and demanding? With such questions in mind, how does the human resource manager strategically plan for their human capital? For example, should candidates be told in detail about the GVT structure during their interview, or should they be allowed to independently learn about it over time?

In previous studies, scholars in the field of international human resource management have clearly established that failures in expatriate international assignments may be due to many factors: inability to adjust to the environment, the lack of tolerance from spouse and children, homesickness, inadequate cultural orientation and preparation from their organization, mismatched levels of expectations regarding achievement and goals, uncompetitive and insufficient compensation and financial packages, and many others (Harzing 1995; Mendenhall & Wiley 1994; Bird & Dunbar 1991; Oddou 1991; Tung 1987).

Nowadays, the work landscape has changed because multinational organizations depend heavily on GVTs to exploit the synergistic values of human capital and eclectic talents working at a distance. The physical workplace has become a virtual workspace offering high mobility, flexibility, and accessibility. As the saying goes, “Two heads are better than one” (or “Alone, we can do so little; together, we can do so much”); this suggests the potential benefits if organizations fully commit to the use of such teams. On the other hand, the lack of opportunity to meet in person may pose psychological, managerial, and behavioral challenges. Despite this drawback, one of the key advantages of GVTs is that firms do not need to send their executives to a foreign country, and thus people no longer need to relocate. Firms can save the cost of expatriation; managers can avoid the stress of culture shock frequently experienced by expatriates; and international human resource managers no longer need to help expatriate employees cope with the multiple issues that come with living in an unfamiliar country.

Yet I question whether the GVT structure can totally eliminate the impact of culture shock, since these teams will include people from different cultures. GVTs are largely dependent on or composed of heterogeneous members. Does this imply that GVT members will experience virtual cultural shock? After all, culture shock can arise from various sources: working with strangers with whom one has no shared historical background and who have diverse communication styles, different uses and functional roles of technology, large time differences, and many others. Obviously, GVT members do not need to undergo the expatriation process and its associated stresses: no relocating agenda, no fuss of travelling for long hours on the plane, no issues of family adjustment, no orientation to a new workplace, no repatriation difficulties when they return home, and so on. But the cultural nuances remain. GVT members will experience culture shock but in a different manner; they will still need to adjust to their colleagues’ cultural nuances and learn to work with strangers in a virtual work sphere.

The findings of my research on GVTs and the use of email have several important implications for the leaders of multinational and international organizations, particularly with respect to cross-cultural collaboration in a distributed environment.

The collapse of the traditional hierarchical structure and the emergence of a more flexible, loose organizational structure provide new opportunities for collaboration by reducing the barriers of geographical distance and time zones. Specifically, my work offers an increased transparency and a greater understanding of the diverse management styles and multiplicity of cultures facing MNCs, and suggests methods for building a more effective cross-cultural training that will boost cultural awareness and sensitivity, teaching appropriate behaviors for overcoming cultural differences, developing intercultural online communication competencies, and designing culturally sensitive information technology applications for effective electronic collaborative and communication tools. All of these practical elements serve the goal of enabling people to collaborate effectively at a distance using a sociotechnical infrastructure that is compatible and congruent with their varying cultural value orientations and ideologies.

Leaders in MNCs who will manage GVTs need to consider several elements that are central to any discussions of culture and GVTs. These elements are based on the following perspectives.

Executives sent on assignment to a foreign country by their parent company are known as expatriates. An expatriate is a person who lives and works in a foreign country, relocating from his or her home country to a host country. Expatriates will generally work in the host country for a certain number of years and need to adjust accordingly. Such adjustment is known as the expatriation process, whereby people learn to behave in accordance with the host country’s norms based on their observations of others. According to the classic model introduced by Oberg (1960), the expatriation process has four phases. The first is the honeymoon phase in which executives or managers experience a sense of euphoria when management asks them to move to another country. Everything seems encouraging and delightful. They are excited, anticipating that they will get global exposure, gain knowledge and expertise, and perhaps get promoted. During the honeymoon phase, expatriates view travel to a new and exciting foreign land as an excellent opportunity. They look forward to a new workplace with challenging tasks and new people with new behaviors, values, and attitudes. At this stage, people usually do not regret the decision to go far away from home. They feel fully prepared to take on the challenges, and, when they arrive at their new workplace, they encounter warm greetings from their new colleagues, a pleasant boss, and a friendly work environment conducive to success.

In Oberg’s second stage, conflicts begin to arise due to culture shock, which is the inability to adjust and assimilate to the new culture in the host country. According to Browaeys and Price (2010), the concept of culture shock was introduced as far back as the late 1950s. Culture shock is defined as the uncertainty and anxiety that arise when people are confronted with a new culture and subsequently experience feelings of loss, confusion, and social and cultural unimportance/low status in the new workplace. Culture shock also occurs when an executive encounters conflicts that are rooted in clashing cultural values, norms, and rituals. As one might expect, culture shock usually leads to unpleasant consequences. Numerous studies have established that many expatriates fail in their international assignments (Bird & Dunbar 1991; Oddou 1991). Instead of staying abroad for the committed number of years, they came back much earlier than expected, sometimes within less than a year. What happened? What are the causes? If an expatriate fails to tolerate and accept the difficulties encountered in his or her new locale, both the home country and the host country management will be disappointed, their colleagues will be left with many perplexing questions, and their families will be apprehensive and disheartened. What is the cause of this expatriation disappointment? Is it due to the difficulty of accepting culturally related changes during this stage?

The third phase in the expatriation process is adjustment or stability. To reach this phase, the expatriate must fully understand the nature and characteristics of the host culture and accept the cultural differences. One of the defining characteristics of culture is that it is learned by a society or group of people over time rather than inherited. Culture is also dynamic (not static) and transferable from one generation to another. Therefore, from a cultural standpoint, the adjustment process, as experienced by an expatriate, can have different outcomes. According to Rice & Rogers (1980), people first go through the process of screening cultural characteristics and selecting which to adopt. People evaluate these new cultural characteristics based on whether they are (1) better or more useful, (2) consistent with existing practices, (3) easily learned, (4) identifiable through trial and error, and (5) recognized as beneficial by all people ascribing to that society. Second, this cultural borrowing is a reciprocal process. People who undergo the organizational and cultural change and the people who are making the changes need to be equally accepting. It cannot be a one-way process. Third, the transference of culture may not be flawless; that is, newcomers to the culture may not recreate or adopt it in its original form; they may eliminate some things and introduce new things. Leaders may model certain practices by making modifications to fit with the current context and culture, both organizational and national. Fourth, it is not easy to transfer the patterns of behaviors, belief systems, and values (p. 179, para 2). As Ferraro (2010) says, “[S]ome cultural practices are more easily diffused than others” (p. 33). There is a strong interaction between organizational culture and the indigenous or local culture. In order to understand the organizational leadership of an organization, we need to observe both the impact of organizational culture on leadership practices and the influence of national cultural values on the development of leadership behaviors.

The last phase is called adaptation. In this stage, expatriates have attuned their minds, emotions, and behaviors to a new way of doing things. Simply awareness and acceptance are insufficient; expatriates must be able to assimilate and acculturate to the new way of doing things in their host country. Some people adopt a certain value because it is similar to their own or because it lets them exercise both their lifestyle and work values. What makes people resist accepting new values? Some of the cultural values observed in the new workplace may not be consistent with their own. Other cultural values take time to change—for example, time orientation. In some cultures, people think nothing of coming to a meeting 15 minutes late; this lateness is part and parcel of the way that they do things at work since, for them, time is not money and is therefore relatively unimportant. This may be difficult to accept for someone from a culture that values time and punctuality and considers it wasteful not to meet due dates and deadlines. Similarly, in a high power distance culture, the boss will walk into a meeting and tell everyone what needs to be done, giving instructions without further discussions. Their authority is a manifestation of the bureaucratic and hierarchical organizational structures within which they function and is a symbol of status, but it may be off-putting to someone who is accustomed to a more collegial boss/employee relationship. All these cultural values embedded in one’s thinking, perceptions, and actions take time to change. People cannot change overnight, even if the organization has trained them in and exposed them to diverse cultural values. Changes in human behavior are hard to achieve because internal change takes longer than changes to systems, infrastructures, and policy. Yet acculturation must take place for expatriates to achieve a smooth adaptation.

Are You Experiencing Virtual Cultural Shock?

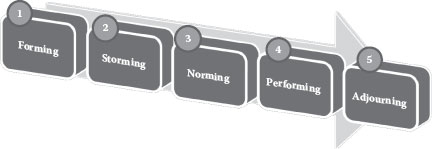

For many decades, knowledge of the expatriation process has allowed organizations to plan for the impact of expatriate employees’ adjustments when they first move to a host country. A new workplace means a high probability of adjustment failure, dependent on the cultural distance between the home and the host country and the degree of shift from the old to the new value orientation. Despite the reduction in culture shock when a person no longer has to travel thousands of miles, a new process of adjustment takes place reflecting the impact of cultural shocks on the virtual work structure. In the GVT context, global leaders still need to manage a similar cultural adjustment process because team members come from many different cultural backgrounds. Global leaders need to understand the team process: how it is formed and how it functions. Tuckman and Jensen’s (1977) teamwork model illustrates the typical process of team development (refer to Figure 14.1).

According to Tuckman and Jensen, in the first phase, forming, members begin the process of getting to know each other. This is an ice-breaker stage wherein members are strangers to one another; they have little or no understanding of the other team members or of their past performance. At this point, people will be in the honeymoon phase; they will be excited and enthusiastic about meeting their GVT colleagues for the first time and looking forward to starting the project, although they have no grounds as yet to trust one another. In the second stage, storming, members may experience conflicts or difficulties in adjusting to their tasks. This stage is where culture shock often occurs. During this stage, the team members undergo a negotiation process in which roles, deadlines, responsibilities, and tasks are spelled out, and a leader is assigned or emerges; this process allows them to begin to understand and trust one another. At this stage, continued conflict or a mishandled crisis can damage this trust that is beginning to develop.

Figure 14.1 Stages of group development. (From Tuckman, B.W. & Jensen, M.C., Group and Organizational Studies, 2, 419–427, 1977.)

During the next stage, known as norming, team members develop a clearer understanding of what needs to be done; norms, procedures, and routines are put in place; and conflicts are resolved. The stage is also known as adjustment because, by this time, team members have learned a little about each other and have begun to trust one another despite their cultural nuances and differences. During the next stage, performing, teams become more comfortable with one another; at this stage, trust is fully developed, and people work as cohesively as possible. This stage also prepares team members for adjustment and, eventually, adaptation, as members become acculturated to the cultural diversity of others.

Global leaders need to manage cultural adjustments and map them against the teamwork model to understand how virtual cultural shock can be minimized or even eliminated in order to achieve a high-performing team. Virtual cultural shock needs to be managed the same way as the normal version. Although the source of virtual culture shock may be different, and its effects are less detrimental, GVT members will still encounter such challenges because the stranger phenomenon is at work. A stranger can be conceptualized when team members are assembled to work on a project without the opportunities to meet each other either before or after the project takes off. It is a common strategy for many MNCs to cut the cost of travelling and expatriation, and thus, oftentimes, members do engage, communicate, and collaborate without meeting with each other face to face and have to learn to develop trust over time. It is only when the initial crisis of adjustment to one another has been resolved that norms are established, team members perform optimally as trust strengthens, the dynamics of the team evolve, and collaboration becomes more solid. The successful accomplishment of intermediate goals will further reinforce the trust that is being built. In the last stage, adjourning, their tasks have been accomplished, and the team members disperse, perhaps experiencing a feeling of loss since they have developed relationships and friendships with their colleagues.

Trust formation varies across the five stages; global leaders need to understand the level of trust and the speed (or slowness) of its growth in each of the stages. Each stage will have different challenges that need to be managed appropriately and in congruence with the cultural preferences and styles of the team’s members.

Bird, A. & Dunbar, R. 1991. Getting the job done over there: Improving expatriate productivity. National Productivity Review, 10(2), 145–156.

Browaeys, M.-J. & Price, R. 2010. Understanding Cross Cultural Management. London: Prentice Hall.

Ferraro, G.P. 2010. The Cultural Dimension of International Business. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Harzing, A.W. 1995. The persistent myth of high expatriate failure rates. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 6, 457–475.

Mendenhall, M.E. & Wiley, C. 1994. Strangers in a strange land: The relationship between expatriate adjustment and impression management. American Behavioral Scientist, 37(5), 605–620.

Oberg, K. 1960. Cultural shock: Adjustment to new cultural environments. Practical Anthropology, 7, 177–182.

Oddou, G. 1991. Managing your expatriates: What the successful firms do. Human Resource Planning, 14(4), 301–309.

Rice, R.E. & Rogers, E.M. 1980. Reinvention in the innovation process. Knowledge Creation, Diffusion and Utilization, 1(4), 499–514.

Tuckman, B.W. & Jensen, M.C. 1977. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies, 2, 419–427.

Tung, R.L. 1987. Expatriate assignments: Enhancing success and minimising failure. Academy of Management Executive, 1(2), 117–126.