Overview of Culture and Cultural Values

Edward Hall (1976), the founder of intercultural communication, asserted that “culture is communication and communication is culture” (p. 191). He emphasized that the types of information exchanged and shared, the reason a communication takes place, the way a person communicates, and to whom a person responds—all of these factors are rooted in the cultural values that a person subscribes to. What is meaningful to a person is based on how he or she perceives his or her world through the cultural lens that he or she holds and the cultural environment in which he or she lives.

Culture is an intricate concept with over 160 different definitions (Ferraro 2003; Schneider & Barsoux 1997; Kroeber & Kluckhohn 1952). One of the earliest and most widely cited definitions is “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by a man as a member of society” (Tylor 1871, p. 1). Ferraro (2001) defines culture as “everything that people have, think, and do as a member of their society” (p. 19).

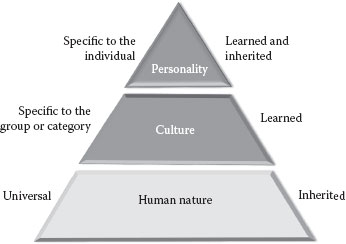

In a similar vein, Hofstede (1980) sees culture as software of the mind or mental programming, analogous to the way that computers are programmed, composed of patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting. He sees culture as one of three layers of human mental programming, with specific components that differentiate it from the other two (see Figure 4.1).

The foundation layer is human nature, which Hofstede (1980) views as “what all human beings, from the Russian professor to the Australian aborigine, have in common: it represents the universal level in one’s mental software. It is inherited with one’s genes” (p. 5). Hooker (2003) places needs like food, shelter, and nurturing in this core set of commonalities that all human beings share. How one meets these needs, however, is derived from the other two layers. For example, all human beings need food; the difference lies in what people eat in different countries.

The second layer is culture. Culture is an intermediate layer between human nature and personality; it is cultivated, shared, and group based. Human beings learn from their experience and their surroundings; this, in turn, shapes their behaviors, attitudes, and values. All aspects of culture can be learned, taught, or observed from one’s family, peers, or environment.

Figure 4.1 Three levels of human mental programming. (Hofstede, G., Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991.)

Culture can be studied from many perspectives (Karahanna et al. 2005; Kaarst-Brown & Evaristo 2002):

1. National—based on a person’s country of origin.

2. Ethnic—based on shared background or descent; for example, Malaysia has three major ethnic groups: (1) Malay, (2) Chinese, and (3) Indian.

3. Religious—based on a shared set of spiritual beliefs, which may cross ethnic and national boundaries; for example, American or Arab Muslims and Chinese or Japanese Buddhists.

4. Gender—based on identification as female or male.

5. Generational—based on membership in an age cohort; for example, distinguishing grandparents from parents from children or elders from youngsters.

6. Social—based on educational background or professional status.

7. Corporate or organizational—based on work-related values arising from the way that people are socialized or oriented to the organization in which they work.

8. Technological—based on a shared technology, which can shape one’s way of thinking, feeling, and acting; for example, norms inherent in technology usage or adoption.

Note that these different kinds of culture may overlap with, align with, or conflict with one another. For example, national culture may align with religious culture, corporate culture may conflict with gender culture, or technological culture may conflict with generational culture. A person may belong to many different types of culture over time, or to more than one at a time, depending on the situation.

The top layer of our programming is personality, which is unique to each individual human being. Personality is partly inherited, partly learned, and partly accumulated over the course of a person’s life. In contrast to culture, personality is acquired over time, as well as inherited. Culture does influence a person’s personality, since acquired over time equates to time spent immersed in a culture. Yet Hooker (2003) emphasizes that within a single culture, a wide range of personalities exists. It is thus misleading to use national character to stereotype all members of a country. For example, it is true to some extent that the Japanese emphasize politeness and tend to be reserved and introverted in nature, whereas Americans are often direct in their statements and possess extroverted personalities. However, there are also Japanese who are outspoken or rude and Americans who are shy or courteous.

In support of Hofstede’s view of culture, Hall (1976) provides a more comprehensive analysis of the way culture touches our daily life:

Culture is man’s medium; there is not one aspect of human life that is not touched and altered by culture. This means personality, how people express themselves (including shows of emotion), the way they think, how they move, how problems are solved, how their cities are planned and laid out, how transportation systems function and are organized, as well as how economic and government systems are put together and function (pp. 16–17).

Despite the many variations of culture, anthropologists agree that culture has three distinct characteristics (Hall 1976):

1. Culture is learned, not innate. People learn how to behave, feel, or think according to what they experience in their social environment because culture is not derived from genetic characteristics.

2. Culture is an interrelated complex whole. Cultures are logical systems and provide coherent parts to a society.

3. Culture is shared by a group or category and is not specific to an individual; rather, it is a collective concept.

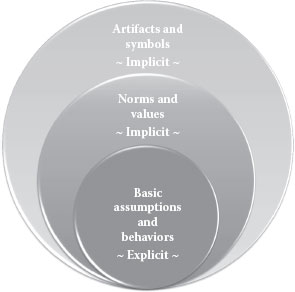

Figure 4.2 The onion model: Manifestations of culture at different levels. (Adapted from Hofstede G., Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991; Schein E.H., Organizational Culture and Leadership, 1st ed., San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985; Trompenaars F., Riding the Waves of Culture—Understanding Diversity in Global Business, Chicago: Irwin, 1994.)

Hofstede (1980) and Trompenaars (1994) suggested an onion model (see Figure 4.2) to describe the different layers of culture, with the degree of complexity increasing as one moves from the outer layers to the core. In the outermost layer is what people have or own, manifested as artifacts or material objects. In the middle layer is what a person thinks, reflected in their beliefs, attitudes, and values. Finally, in the innermost layer or core is what people do, determined or at least colored by their normative patterns of behaviors and assumptions.

Artifacts, Products, and Symbols

At the outermost layer of the onion are artifacts, products, or symbols, visible as gestures, words, images, or objects. People within the same culture share a common set of these symbols. One example is jargon (specialized words or language used by certain groups of people to describe their work). For example, medical doctors use different terms from the average person to explain a flu, while lawyers have ways of explaining a contractual agreement that laymen may not fully understand. This outermost layer is explicit, superficial, changeable, easily copied, or modified by other groups and consists of behaviors that are easily recognized or observed.

According to Gudykunst and Ting-Toomey (1988, p. 61), norms are “prescriptive principles to which members of a culture subscribe.” The underlying hypothesis of cultural value studies is that people from different cultures differ normatively in their value orientations, which ultimately results in differences in the overt behaviors that are exhibited by many of the people much of the time. Hofstede (1991) defines values as “a broad tendency to prefer certain states of affairs over others” (p. 8). Schwartz’s (1992) definition is more elaborate, stating that values are “desirable states, objects, goals, or behaviors, transcending specific situations and applied as normative standards to judge and to choose among alternative modes of behavior” (p. 2). In support of this latter definition, Scarborough (1998) asserts that values are, in large part, culturally derived and, as a result, cultural values drive a person’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

Basic assumptions are the implicit or hidden aspects of culture that spring from needs at the core of human existence (Trompenaars 1994). Basic assumptions are the behavioral rules that regulate actions and guide people to workable ways of managing their relationships with the environment (external adaptation), as well as with other people (internal integration) (Schneider & Barsoux 1997). At this core layer, behaviors often have unconscious motivations because basic assumptions are not articulated and are taken for granted. Several scholars have identified specific dimensions within this layer of culture: (a) Hall (1959, 1976) concerning time, space, and context; (b) Hofstede (1980) concerning work-related values; and (c) Trompenaars (1994) concerning business values. (See Chapter 6 for a more detailed discussion of these.) Hofstede’s work on basic assumptions has enhanced our understanding of the complexities of culture, a vital perspective for organizations or people who need to work together to find solutions to shared problems.

Ferraro, G.P. 2003. The Cultural Dimension of International Business. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gudykunst, W.B. & Ting-Toomey, S. 1988. Culture and Interpersonal Communication. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Hall, E.T. 1959. Silent Language. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Hall, E.T. 1976. Beyond Culture. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Hofstede, G. 1980. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hofstede, G. 1991. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hooker, J. 2003. Working Across Cultures. Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Kaarst-Brown, M. & Evaristo, J.R. 2002. International cultures and insights into global electronic commerce. In P. Palvia, S. Palvia & E. Roche (Eds.), Global Information Technology and Electronic Commerce, 4th ed. (pp. 255–276). Marietta, GA: Ivey League Publishing.

Karahanna, E., Evaristo, J.R. & Strite, M. 2005. Levels of culture and individual behavior: An integrative perspective. Journal of Global Information Management, 13(2), 1–20.

Kroeber, A.L. & Kluckhohn, C. 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. Papers, 47 (1). Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

Scarborough, J. 1998. The Origins of Cultural Differences and Their Impacts on Management. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Schein, E.H. 1985. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, S.C. & Barsoux, J. 1997. Managing Across Cultures. London: Prentice Hall.

Schwartz, S.H. 1992. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

Trompenaars, F. 1994. Riding the Waves of Culture—Understanding Diversity in Global Business. Chicago: Irwin.

Tylor, E. 1871. Origins of Culture. New York: Harper & Row.