Why GVT Leaders Need Intercultural Competencies

Intercultural Competency Is Indispensable to Global Virtual Teams

Why does culture matter in a teamwork environment? Specifically, in what ways does culture matter when teams are collaborating in a virtual space—when they are working together at a distance? Hall (1976) asserted that “culture is communication and communication is culture” (p. 65). A person’s culture and communication cannot be separated, since both are intertwined and interdependent in terms of attitudes, values, and behaviors. The research that I have conducted clearly demonstrates that cultural behaviors are derived from the communication style and that the communication style is rooted in cultural values.

Challenges arise when teams use computer-mediated technology for communicating because such platforms lack the nonverbal cues that are essential for cultures that depend on context for effective communication. Other cultures depend largely on text, whether written or verbal; for them, using computer-mediated technology as a platform for collaboration makes cultural differences less salient, thus equalizing the team members’ ability to work together. Inevitably, a wide range of challenges can arise that intensify the effects of culture on global virtual teams (GVTs); such issues need to be directly and openly addressed, hence the need for global leaders to have strong cultural competencies. Past studies have clearly established the contradictory effects of culture on the GVT performance. Whereas some scholars agree that culture does influence the way people manage and collaborate in a team setting (Cogburn & Levinson 2003), others argue that culture has no impact on the way that people collaborate when using computer-mediated communication (CMC) (Shachaf 2008).

The readiness of an organization to fully employ the GVT work structure is directly dependent on developing GVT leaders and team members who are culturally competent. In this chapter, I present what I call the cognition, emotion, and behaviors (CAB) of intercultural competency. These three aspects form the answers to crucial questions such as “Are you aware of and knowledgeable about different cultural values? Can you tolerate and be sensitive to the cultural nuances of others? Can you emulate and then acculturate to new cultural values and reshape your behaviors accordingly?” First, however, let us define the concept of intercultural competency.

What Is Intercultural Competency?

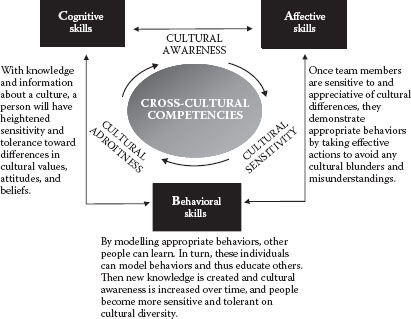

Ferraro (2010) defines culture as “everything that people have, think and do as members of their society” (p. 20). In the “Cultural Characteristics” section in Chapter 4, I use the onion model (Barsoux & Schneider 1998) to illustrate the many layers of culture: artifacts, values/beliefs, and basic assumptions and behaviors. GVT leaders need to be familiar with Ferraro’s definition, as well as the idea of multiple layers of culture, in order to competently manage team members with different cultural backgrounds. Koester et al. (1993) conceptualized intercultural competence as having three aspects: (1) culturegeneral understanding, (2) culture-specific understanding, and (3) positive regard of the other. Chen and Starosta (1997) suggested that the process of developing intercultural communication competence also has three aspects: (1) cultural awareness, (2) cultural sensitivity, and (3) cultural adroitness. These findings suggest that leaders need to observe what people think and do by practicing awareness, sensitivity, and specific behavioral approaches. One way of thinking about this is the CAB Intercultural Competency Framework, discussed in depth as follows.

Acculturation is the process whereby people learn to behave in a particular way based on their observations of a cultural role model. In the context of GVTs, team members need to fully understand the cultural differences present within the team before acculturation can take place. Each member of the team needs to acknowledge and recognize how he or she works within the team environment, as well as how and why others work the way that they do. Team members must not only tolerate but also accept these differences if their heterogeneous team is to be successful. An important role of the GVT leader is to model proper behavior for their team and help their team members become aware of their behavioral characteristics. Acculturation is not merely about changing one’s personality or character; rather, it means each person adapting to and shaping the way that the team works so that the team can blend together into a smoothly functioning unit. The GVT work structure also demands changes in the way that people communicate and collaborate since it requires the use of CMC, including social media tools such as Facetime, Skype, WhatsApp, Twitter, Messenger, and so on.

Some might question the need for culturally competent GVT leaders when the team members may never meet in person, since they are collaborating at a distance. In fact, GVT leaders will confront many cultural idiosyncrasies, even—sometimes, especially—in the virtual workplace. For example, team members will likely bring to the table different management practices, communication styles, decision-making and negotiation styles, conflict resolution methods, and time management ideas, among other things. Skilled GVT leaders will be able to find the right fit and balance between their own cultural values and the new multicultural context in which they are now operating. Additionally, leaders will need to encourage cultural awareness within the team using the knowledge and information that they acquired during cross-cultural training and instill cultural sensitivity by fostering tolerance and appreciation and by modeling the desired behaviors. In other words, they need to take action in the right way.

To build high-performing GVTs, organizations must develop cross-cultural competencies in their employees. These cultural competencies need to align with and accommodate the GVT work structure. To be effective leaders, as well as managers, employees will need to develop strong cultural competencies, incorporating a high level of cultural awareness, sensitivity, and behavior. With respect to GVTs, team members need to develop a similar set of skills as expatriates who travel, work, and live in another country. Unlike expatriate employees, GVT members need not adjust to living abroad, but, in a sense, they are still working abroad, and, as such, they will undergo the same cognitive and emotional challenges of adjusting to people of different cultures. The process is similar to the expatriation adjustment process, though without all its phases. For example, working with new colleagues who are total strangers may require a high degree of awareness of how others think and function. People need to be culturally savvy when working with others who have different work styles, time management habits, decision-making processes, negotiation skills, and so on. These differences may be detrimental to team success if they are not properly understood and appreciated.

CAB Intercultural Competency Framework

Cultural competency has three aspects, which, together, form the basis for the CAB Intercultural Competency Framework (Zakaria 2000; Chen & Starosta 1997):

1. Cognitive—cultural awareness—what is culture, and who is affected by it? At this level, people form perceptions about others who are different from themselves. They begin to form perspectives about others, with or without any background knowledge about the specific culture. This aspect, if not modified by the other two, can lead people to formulate stereotypes, defined as a generalized opinion about all the members of a cultural group based on limited knowledge. GVT members will need both general and culture-specific training on what to do and what not to do so as to form accurate, well-rounded perceptions.

2. Affective—cultural sensitivity—why do we need to understand people who are different from us? At this level, team members may feel threatened or uncomfortable when their way of working is questioned by others. Those who are ignorant of these differences, and of the stress created by them, may unintentionally offend or hurt others.

3. Behavioral—cultural adroitness—how can we better understand other people’s differences? What actions can we take that are appropriate and relevant to the people whom we are leading and managing? When ought we to behave in accordance with a cultural condition or situation? This can be challenging for people with no experience working in an environment where different cultural values come into contact. Team leaders without such experience may not know what to do or how to behave respectfully toward other cultures.

Figure 15.1 demonstrates how these three aspects feed into one another and can be used as a basis for developing all three types of cross-cultural competencies: behavioral, cognitive, and affective (Zakaria 2008).

Figure 15.1 CAB Intercultural Competency Framework. (Adapted from Zakaria, N., The possibility of water-cooler chat? Developing communities of practice for knowledge sharing within global virtual teams, in M. Raisinghani (Ed.), Handbook of Global Information Technology, Chapter IV (pp. 1–14), New York: Information Science Reference, 2008; Chen, G.M. & Starosta, W.J., Human Communication, 1, 1–16, 1997.)

Some people find working with colleagues from different cultures appealing and exciting, whereas others find it frustrating and challenging. The key questions are whether or not such experiences help to develop and build cultural competency, whether or not they enable participants to discover more about themselves and their own culture, and whether or not it helps participants to know others better.

For example, some people may express frustration with working across time zones since it makes it difficult to interact in real time. Team members in Asia, for example, will be 12 hours apart from their colleagues in North America. Members from the same time zone may end up discussing team business among themselves, leaving their colleagues from other time zones to catch up when they awake. Or ideas may be deliberated at different times, making it difficult to reconcile and negotiate in real time, unless members are willing to split the difference (some stay up late; others get up early) or delay the decision-making process. Many people report that waiting up for meetings off their accustomed time schedule makes them exhausted and anxious. Others report feeling demotivated when their colleagues are not collaborating. Team members may fail to communicate these concerns and simply keep their silence. With such a wide range of cultural challenges, it is important for all team members to be aware of the nuances of cultural values that affect the development of the trust that is necessary for achieving a cohesive team. Some team members will develop a high level of trust for their colleagues based on demonstrated progress toward the set goals—for example, if they see their colleagues working hard to meet deadlines. This approach is known as task orientation. Others will trust their colleagues only after developing a relationship with them—for them, trust evolves naturally over time. This approach is known as relationship orientation. Given these cultural differences, GVT leaders need to carefully manage and harmonize the first stages of forming the team. How can the GVT leader develop a balanced strategy? For example, he or she needs to create a warm and welcoming climate for a group of strangers who are coming into contact with one another for the first time. Some kind of ice-breaker activity may speed up the rapport-building stage for those who are relationship oriented. At the same time, for those who are task oriented, the leader will need to incorporate the agenda and goals of the project so that these team members feel a sense of direction and clearly understand the goals.

Organizations, for decades, have spent time planning and organizing various kinds of training for their executives who will be going abroad for international assignments. The same type of training is necessary for those who are virtually going abroad through a GVT. The aim of all these cross-cultural training sessions is to increase the cultural competency of GVT leaders and members who will be working with people from different cultures—an experience similar to that of expatriates. The following subsections explore the three parts of the CAB model in detail.

Understanding cultural differences usually takes place at the cognitive or thinking level. Cultural competence begins with knowledge about cultural diversity. Cultural values are normally learned first at the cognitive level—whether learning about other cultural values or about one’s own cultural values. At this initial stage, information about unfamiliar culture(s) needs to be first acquired and then fully understood; this may include differences surrounding the basics such as food, climate, language, geography, time, and so on. This cognitive process relies on increasing self-awareness: a good understanding of one’s own cultural peculiarities. With this improved understanding, a person can learn to better appreciate others’ differences, as well as accurately predict the effects of their behavior on others.

Additionally, at the cognitive level, a person needs to have relevant information and an understanding of culture. Only with the appropriate cultural training, the cultural knowledge can be fully acquired. At this level, once a person obtained concrete knowledge, it allows one to accurately interpret and make sense of the cultural situation that is faced by them. Also, with cultural knowledge, a person will use their intellectual capability to analyze and reason out the cultural challenges faced. Solid cognitive intellectual capacity of cultural differences will lead to cultural sensitivity.

Thus, awareness of oneself and one’s own culture is as important as awareness of another’s. At the cognitive level, people are expected to know two things: (1) themselves and (2) others. Yet it is difficult for a person to learn about others if he or she does not fully know why he himself or she herself does things the way that he or she does. The phrase knowing me, knowing you summarizes a balanced approach in which people discover their own and others’ cultural values, attitudes, and beliefs. It is human nature not to question one’s own culturally learned behaviors—but, when one observes people from another culture and compares what they do with what one normally does, it opens one’s eyes. Therefore, a leader needs to learn about the most basic layer of culture by searching for information and building a knowledge base about the new culture(s) that he or she encounters. At this level, both the organization and the leader are responsible for obtaining as much general and specific cultural knowledge as possible.

To have the best hope of success, an organization must provide cross-cultural training for its employees who will be leading GVTs, with the goal of helping managers effectively integrate their GVT members into a cohesive whole. Leaders need to think creatively about how to balance their team’s diversity of cultural backgrounds. This is less challenging, obviously, for a leader whose team members all originate from a single country or from culturally similar countries. For example, suppose that a leader from Thailand is asked to manage a team that includes members from South Korea. The leader needs to understand a single new set of cultural values (South Korean). But suppose that a leader from America is asked to manage a GVT that is composed of members from Spain, Japan, and India. This leader now needs to be equipped with an understanding of three new cultures. This is the scenario that MNCs often face. The most important skill to develop at this stage is a high level of cultural awareness, built on a thorough knowledge of the culture(s) in question and a mind-set that is attuned to diverse cultural values. Such leaders need to be open minded and mentally prepared so that they can avoid the stereotypical perceptions of members from other cultures.

At the second level of cultural competence, a person will develop emotional intelligence that is useful for understanding culture, and it involves affective skills. A person is required to look deeper than simple cognitive knowledge or logic. Once we accept someone’s cultural differences at the rational and cognitive level, we can be tolerant and appreciative of their uniqueness. With concrete cultural knowledge, at the affective level, a person is expected to develop a high level of sensitivity when confronted with cultural frustrations. Once a person is considerate and appreciative of cultural differences, they will also become composed, patient, and flexible when faced with myriad cultural complexities. It also becomes easier for a leader to acknowledge that he or she is different and to ensure that such differences will not be a barrier to working together. A person will try to adjust and take preventive measures to overcome the differences. At this level also, a person will use their own intuition, wisdom, and values to make sense of cultural synergies that are obtained by working with others. In a similar vein, with a strong cognitive foundation, global leaders would become fully aware of cultural differences, which, in turn, can make them sensitive to cultural nuances.

What is cultural sensitivity? Cultural sensitivity is when a person is able to put himself or herself in another’s shoes, to accept the differences with an open heart and without emotional strain. Cultural sensitivity is difficult to achieve because human beings often become emotional when faced with a situation that they cannot comprehend. Instead of reasoning things out cognitively, based on logic or knowledge, people tend to resort to emotions. To overcome this, people must learn to make inferences and interpret various types of communication. For example, people need to be familiar with both verbal and nonverbal communication patterns so that they can communicate equally well with both people who depend heavily on words and people who rely on cues such as facial expression, body movements, gestures, personal space, and so on. They can then be more sensitive to the body language of others.

To take another example, a person may be aware that, in Asian countries like Malaysia or Indonesia, people generally have a relaxed attitude toward time and are therefore not always punctual. To an outsider, this may come across as a lack of urgency or poor time management. Deadlines may need to be extended. According to Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1997), a culture that ascribes to a monochronic time dimension, as do many Western countries (e.g., the United States, Germany), will adhere to time strictly. Time is viewed as linear in which only one thing takes place at a time. On the other hand, for people belonging to a polychronic culture (e.g., Thailand, Indonesia), time is flexible, and people can do many things at once. Imagine a GVT leader who needs his or her team to make an important decision; now, imagine that the team is composed of members from both monochronic and polychronic cultures. How might a leader with such knowledge accommodate such differences when he or she needs every team member to make decisions on time and punctually? The leader will need to educate his or her team about such differences so that they can appreciate the timeline of the work and acknowledge an appropriate sensitivity to time. As stated earlier in this section, cultural sensitivity means the ability to perceive and adapt to different situations in order to achieve harmony and cohesiveness among colleagues from diverse cultures.

By being culturally sensitive, a person will be more observant and perceptive of one’s own actions and others’ actions. A person will naturally adapt and mimic the behaviors of others to obtain culturally appropriate behaviors. Hence, appropriate behavior occurs when people have sufficient basic and specific knowledge about a culture and have learned to be tolerant, responsive, and open to cultural differences. Only then can he or she demonstrate acquired behavioral skills. Armed with both knowledge and sensitivity, people will perform more effectively and efficiently in the workplace and interact cohesively in a GVT.

However, it is not easy to correctly emulate a cultural behavior without a solid understanding of and sensitivity to that culture. Human behaviors are complex, even more so when rooted in different cultural values. Culture is also complex, and this combination of complexities makes it exceedingly difficult for change to happen at the behavioral level. Human behaviors cannot be changed overnight. It takes time to change attitudes, perceptions, and values. Only when a leader keeps an open mind to see and acknowledge the differences within his or her team and an open heart to readily accept and appreciate those differences can the appropriate behaviors be modeled and, ideally, emulated. At this stage, a person may achieve acculturation, wherein he or she has learned to accept, adapt, and then replicate what is observed. This process is easier when the person is convinced that there is a good reason for doing so and is the last stage of achieving cultural competency. A person can also become innovative through re-creation by performing an action that is based on his or her understanding and knowledge of culture. Once the innovative actions and behaviors are acceptable to others in a particular culture, that new knowledge is further added to the cognitive intellect of a person.

In the GVT context, people often work with strangers in a virtual space and cannot observe their physical behaviors. For such behaviors to be solid, a leader needs to model the desired behavior for his or her team members. For example, a communication style that is direct and straightforward can be perceived as rude and harsh by a culture that appreciates subtlety and indirection. How can a GVT leader steer deliberation, the discussion of issues, and decision making if he or she is not sensitive to the various ways that people communicate? How can a GVT leader avoid cultural blunders that might harm the group relationship or negatively affect the task to be accomplished? Leaders need to take a proactive role in modeling the right behaviors for their team. Once the leader shows the correct way to behave in a culturally fraught situation, the members can follow suit; this, in turn, promotes a sense of bonding among the members because they can then work in a more cohesive manner. Through the right conduct and actions, members will gain cultural experience and can subsequently educate others on what is appropriate and inappropriate. Creation of new knowledge will increase as more people gain experience working in GVTs.

A leader might have a so-called cultural blind spot, meaning they do not know what a given culture considers required, acceptable, or taboo. A cultural blind spot could indicate simple ignorance, or it may imply that the person fails to take into account anything other than what he or she personally finds acceptable. Such a person is referred to as ethnocentric, meaning they hold the belief that their way of doing things is the best way. GVT leaders need to model culturally appropriate behaviors by acting in ways that are appropriate and relevant to the team that they are managing.

In sum, these three aspects are presented as a set of guidelines for GVT leaders to use in developing their cultural competency (see Chapter 17). The model is not only based on sequential stages; it also introduces a cyclical process wherein any of the stages can take place first and be followed by any of the others. Cultural knowledge is required before the affective/emotional aspect can be reached, and it presents the third stage (behavior) as result[ing] when people have sufficient basic and specific knowledge about a culture and have learned to be tolerant, responsive, and open to cultural differences. As the name CAB denotes, these represent the basic ingredients for a skillful leader of GVTs. It is useful to note that cultural challenges can arise at any of the stages, and different competencies may be required. An affective issue may arise when a leader reacts emotionally to a cultural disparity; with the right knowledge, however, the leader can suppress his or her instinctive reaction and instead respond with more sensitivity. The cognitive stage may be a trigger point for someone who is ignorant of cultural differences, but, when equipped with the appropriate knowledge, the person may be more appreciative of what he or she perceived at first as silly or ridiculous. The behavioral stage can be puzzling or irritating when a leader observes certain behaviors. As such, the stage can also be an initiating process when a leader observes certain behaviors that are not the norm—but, if the leader has the requisite cultural knowledge, he or she can recognize the roots of the behavior and resolve the issue.

In addition to the CAB intercultural framework, there are many other dimensions on which leaders can build competency. For instance, Adrian Furnham (http://adrianfurnham.com), a renowned behavioral psychologist and professor with experience in teaching more than 28 nationalities in the United Kingdom, points out that “The world is getting smaller each day and although we may be ethnically different, human beings are quite homogenous” (Friday Magazine). He argues that leaders can be trained and developed and that there is not necessarily such a thing as a born leader. Cultural differences need not be a barrier to becoming a competent global leader, since any individual with sufficient inspiration and dedication can choose to educate himself or herself culturally. Furnham identifies seven dimensions that organizations can use when developing cross-culturally competent leaders (see Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Dimensions of Global Leadership in the Context of GVTs

Leadership Dimension | Cultural Context |

Cultural immersion | Ability to acculturate to a new environment with different cultural values, beliefs, and behaviors |

Capability | Possession of the necessary leadership skills, both in qualifications and experience |

Care | Ability to be compassionate, to express empathy for and care about the well-being of those whom they lead |

Connection | Ability to interact effectively with a variety of people, develop relationships, and make connections easily |

Consciousness | Awareness of one’s surroundings and of the changes in one’s environment, particularly when dealing with cultural diversity |

Context | Possession of a well-defined perspective for developing measures and strategies to cope with a GVT’s cultural dynamics |

Contrast | Ability to compare cultural behaviors |

Barsoux, J.-L. & Schneider, S.C. 1997. Managing Across Cultures. London: Prentice Hall.

Chen, G.M. & Starosta, W.J. 1997. A review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity. Human Communication, 1, 1–16.

Cogburn, D.L. & Levinson, N.S. 2003. US-Africa virtual collaboration in globalization studies: Success factors for complex, crossnational learning teams. International Studies Perspectives, 4, 34–51.

Ferraro, G.P. 2010. The Cultural Dimension of International Business. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hall, E.T. 1976. Beyond Culture. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books/Doubleday.

Koester, J., Wiseman, R.L. & Sanders, J.A. 1993. Multiple perspectives of intercultural communication competence. In R.L. Wiseman & J. Koester (Eds.), Intercultural Communication Competence [International and Intercultural Communication Annual], 17 (pp. 3–15). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Shachaf, P. 2008. Cultural diversity and information and communication technology impacts on global virtual teams: An exploratory study. Information and Management, 45(2), 131–142.

Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. 1997. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Zakaria, N. 2000. The effects of cross-cultural training on the acculturation process of the global workforce. International Journal of Manpower, 21(6), 492–510.

Zakaria, N. 2008. The possibility of water-cooler chat? Developing communities of practice for knowledge sharing within global virtual teams. In M. Raisinghani (Ed.), Handbook of Global Information Technology, Chapter IV (pp. 1–14). New York: Information Science Reference.