Chapter 18

Building a Foolproof Set

In This Chapter

![]() Driving the rhythm

Driving the rhythm

![]() Selecting the right key for harmonic mixing

Selecting the right key for harmonic mixing

![]() Developing a style all of your own

Developing a style all of your own

After you’ve taken a look at the different ways you can mix your tunes together (refer to Chapters 14, 16 and 17), you need to start examining the tunes you’re using in the mix.

As well as looking a bit more closely at why a tune can mix well with one tune but not another, this chapter covers developing your own style when DJing rather than simply replicating all those who’ve come before you. No one’s saying that following the same fundamentals as other DJs is wrong, but if you can think about what you’re trying to do with the order of the tunes in your mix, you’ll be a lot better DJ than the one who only focuses on mixing tune A with tune B just because they sound good together.

Choosing Tunes to Mix Together

The tunes you select and the order in which you play them are just as important as the method you use to get from tune to tune. The best technical mix in the world can sound terrible if the tunes don’t play well together, and boredom can set in if you stick to the same sound, genre and energy level (pace and the power of the music) all night.

In order to get a feel for what kinds of tunes mix well with each other, you need to consider the core differences (other than the melody, the vocals, the instruments used and so on) that make tunes of a similar genre different from one another. These core differences are the driving rhythm, the key in which the tunes are recorded, and the tempo at which a tune was originally recorded.

Beatmatching – the next generation

Matching the pounding bass beats of your tunes is one thing, and after you get the knack, playing the bass drums of two tracks together is simple and sounds good with the correct attention to EQ (equaliser) control (see Chapter 16). However, the bass drum is just the beat. The core driving rhythm is a rhythm that you need to consider and listen out for in tunes, and it isn’t just evident in dance music. All music is made up of combinations of core driving rhythms.

If what follows sounds a little childish, that’s because it is. I remember it from school, so thanks to Mr Galbraith for making this concept stick!

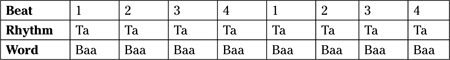

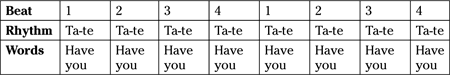

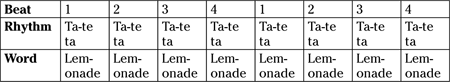

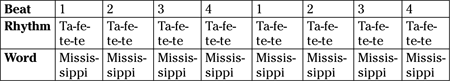

When beatmatching bass drum beats, you only have to consider the solid thump thump thump thump of the beats playing over each other. Now you need to listen out for one of the four driving rhythm fundamentals too: ta, ta-te, ta-te-ta and ta-fe-te-te. Most popular music has four beats to a bar, and each of the driving rhythm sounds occurs on the beat, so you get four of each to a bar:

Ta is just a single sound on each beat of the bar (sounds like baa from the nursery rhyme ‘Baa, Baa, Black Sheep’):

Ta-te are two sounds of equal length on each beat (sounds like Have you in the line ‘Have you any wool’ from ‘Baa, Baa, Black Sheep’):

Sometimes you don’t hear the ta (Have) part of the rhythm, and just hear the second, te (you) part, known as an offbeat. This simple offbeat is a favourite rhythm for producers who want a powerful, stripped-down sound to a tune.

Ta-te ta is like saying lemonade on each beat. It’s very similar to ta-te, except that instead of two equal sounds you get two quick sounds (which take up the same time as ta in the ta-te rhythm) followed by one sound that lasts as long as the te half of ta-te. Splitting the ta-te ta rhythm into two, the halves are ta-te and ta (Lemon and ade). You say lemon very quickly, and it lasts the same duration as ade:

Ta-fe-te-te is like saying Mississippi on each beat of the bar; four equal sounds to each beat give a powerful, hypnotic rhythm to the tune. This sound is the duggadugga rhythm I mentioned earlier for ‘I Feel Love’. It adds a lot of energy to a bass melody, and if you add a filter or a flanger effect to this rhythm (see Chapter 10), it leaves the dance floor in a trance.

Producers combine these driving rhythm fundamentals with each other to make unlimited combinations of rhythms when writing tunes. For instance, they might use three ta-te tas followed by a ta-fe-te-te to make up one bar, or get even more complicated and create bars with ta, ta-te, ta, ta-te-ta driving rhythms.

When considering what tunes to use in the mix, listen to how well these driving rhythms play over one another. A good fallback is that if a complicated multi-layered driving rhythm contains a ta-fe-te-te foundation in its make up, you can treat the tune as though it’s an entirely ta-fe-te-te driving rhythm.

Mixing with care

Mixing between similar driving rhythms can be a bit tricky. In the right hands, ta-fe-te-te (Mississippi) mixes in beautifully to another ta-fe-te-te, and this constant driving rhythm is what often adds a feeling of power and energy to the mix. But if you don’t precisely beatmatch the tunes, the four sounds fall in between each other, giving eight very messy sounds. The same goes for ta-te ta: you need good beatmatching skills to mix two of these driving rhythms together (or to mix ta-te ta into ta-fe-te-te).

Mixing simpler ta or ta-te rhythms with each other (including the offbeat part of ta-te, where you only hear the second te sound) or into either of the more complicated rhythms (ta-te ta and ta-fe-te-te) is a solution to this mixing challenge. However, this method will eventually stifle your creativity (and often the energy of the mix). If you need to go from a complicated driving rhythm to a simple one and then back again to a complicated one in order to progress through a mix, you’ll break up the flow of the set. That’s why spending time to refine your beatmatching skills is important, so that you’re happy mixing complicated driving rhythms.

Changing gear

Mixing from one driving rhythm to another is extremely important to the power of the set. Going from a ta rhythm to ta-te ta can make the mix sound faster and more intense, even if the beats per minute (bpm) are still the same. Changing from ta-fe-te-te to the offbeat version of ta-te (only the te part) is an incredibly effective way of making the mix sound darker by simplifying and concentrating the sound from a frantic rhythm to a simple, basic rhythm. When coupled with a key change (see ‘Changing the key’ later in this chapter), the effect can lift the roof off!

Getting in tune with harmonic mixing

Your beatmatching may be perfect (see Chapter 14), your volume control may be spot on (see Chapter 16) and you may have chosen two tunes with complementary driving rhythms, but sometimes two tunes sound out of tune with each other. Harmonic mixing comes in at this point, and is the final step for creating truly seamless mixes. Harmonic mixing isn’t an essential step of the mixing ladder by any means, and it may be something that party and rock DJs never consider, but as an electronic dance music DJ, if you want to create long, flowing, seamless mixes, harmonic mixing certainly plays a very important part.

Most DJs first approach harmonic mixing by accident and then try to improve through trial and error. Trial and error is extremely important. Blindly following the rules that I give in this section for what key mixes into what is a bad idea. Knowing how the key affects how well tunes mix together is important, but more important is developing an ear for what sounds good when tunes are mixed together, rather than referring to a rule.

However, you need somewhere to start from and somewhere to turn to if you’re unsure what to do next, which is where the principle of key notations comes in. You have a choice of two systems to help you understand. Brace yourself here. The terminology surrounding key notations may seem like a foreign language, but don’t worry – it’s not something to be scared of.

Traditional key notation

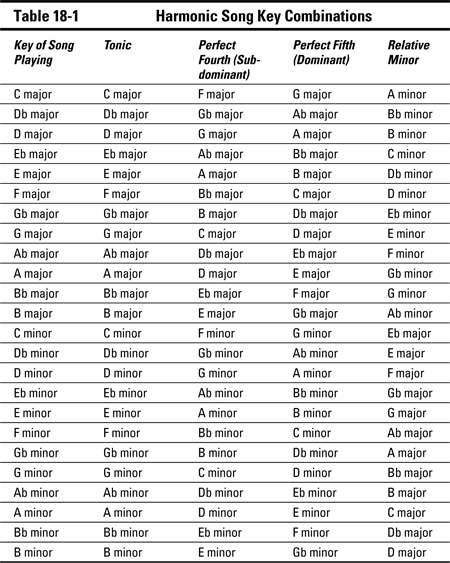

In the Western world, music has 24 different keys: 12 major and 12 minor. This is known as the traditional key notation system. Whether a key is major or minor depends on the notes you use to create that key. Each key mixes perfectly with four keys and mixes to an acceptable level with two other keys, as shown in Table 18-1. Don’t worry if Table 18-1 looks like nonsense; there’s an explanation of what it means at the end of the table!

It’s okay, don’t panic; calculating which keys combine best with each other is actually very simple. In Table 18-1, look at C major and then look at the keys written next to it. C major obviously mixes with a tune with the same key as its own (known as the tonic), but it also mixes beautifully with the three keys next to it: F major, G major and A minor. However, because C major works really well with A minor, you can also incorporate the keys that A minor works well with. These key combinations from A minor are acceptable rather than perfect. You have to judge for yourself whether they match well enough for what you’re trying to do (which is why it’s important to use your ears to gauge the sound of a mix, rather than just referring to a chart).

This chart is kind of mind-blowing though, and isn’t easy to read. The minor/major thing is a bit confusing if you don’t have any musical experience, and working out what mixes into what can take a while. Fortunately, Mark Davis at www.harmonic-mixing.com developed the Camelot Sound Easymix System, which takes the confusion out of working out what key mixes with what.

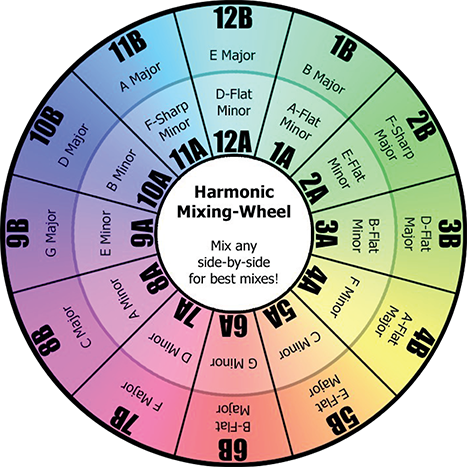

Camelot Sound Easymix System

The keys that mix harmonically are identical to those in the traditional notation, but rather than looking at a confusing table you only need to look at the keycode for the key of the tune that you’re playing, and then look to the left and right and directly above or below, depending on whether the key you’re referring to is on the inner or outer ring of the diagram.

So if your tune is 12B (E major), you can mix it with a tune with the same key, with 11B, 1B from the same major family, but you can also mix it perfectly with 12A from the minor ring and you may get a nice result mixing into 11A and 1A tunes.

The system works perfectly if you calculate each of your tune’s keys and play them all at zero pitch, never changing their speed. But when beatmatching, you need to alter the speed of your tunes to make the beats play at the same time. On normal CD decks and turntables, the pitch of the tune changes as you change the speed (which is why it’s called a pitch control rather than a speed control), and the original key starts to change into a new one. Therefore, when using the Camelot Sound Easymix System, for every 6 per cent you change the pitch, you need to change the keycode by seven numbers according to their system.

(Copyright 2001, Camelot Sound/DJ Pulse, used with permission)

Figure 18-1: The Camelot Sound Easymix System.

For example, if you have a 3B tune and pitch it up to 6 per cent, it’s no longer a 3B tune but is now a 10B tune. Or if you pitch the tune down by 6 per cent, it becomes an 8B tune. Move around the circle by seven segments to see for yourself. A 6 per cent pitch change means that the 3B tune is no longer suited to 4B, 2B, 3A, 4A and 2A. For a good harmonic mix, you need to choose tunes which, when you adjust their pitch so you can beatmatch them, play with a keycode of 11B, 9B, 10A, 11A or 9A.

If you’re DJing with turntables, the success of this 6 per cent keycode adjustment can depend entirely on how accurate your turntables are. Use the calibration dots on the side of the turntable to see whether the turntable truly is running at 6 per cent. (Refer to Chapter 6.)

Harmonic mixing is a vast concept that you can bend, twist, break or ignore at will, and the extreme concepts could take up ten of these books. If you want to delve deeper into the theory of harmonic mixing, visit DJ Prince’s website, which is dedicated to harmonic mixing. Visit www.djprince.no when the mood strikes, and say hi from me – or take a look at an incredibly detailed book called Beyond Beatmatching by Yakov Vorobyev and Eric Coomes.

Keying tunes

Both the traditional and Camelot notation systems may sound helpful, and you’ll soon find they’re very simple and easy to understand, but one thing is still missing: how do you determine the keys of your tunes?

The three different ways to work out the key of a tune are:

- Review online databases: DJ forums and websites across the Internet offer huge databases of song keys. The people who created the Camelot Sound Easymix System have a subscription-based database at www.harmonic-mixing.com, and forums like www.tranceaddict.com/forums have huge numbers of posts dedicated to the keys of tunes, old and new.

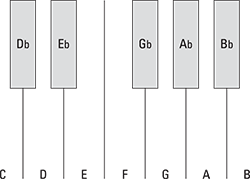

- Use your ears: Figuring out the key by ear is by far the hardest work, taking patience, a good ear for music and a fair bit of musical theory knowledge. Here’s one way to do it:

- Play the tune at 0 pitch on the turntable/CD player.

- Use a piano/keyboard or a computer-generated tone to go through all 12 notes on the scale, as shown in Figure 18-2.

Figure 18-2: The 12 notes on a piano scale.

- The note that sounds the best and melts into the music is the root key (the C in C major, and so on).

Finding whether the key is minor or major takes the whole thing to another level of complication, and if you want to go into that in detail you need to start looking at musical theory books. Check out books like Guitar For Dummies, 2nd Edition, by Mark Phillips and Jon Chappell, and Piano For Dummies by Blake Neely (both published by Wiley), because they explain this theory in a way that’s easy to understand.

I’m a drummer at heart and have zero musical theory knowledge, so the way I was taught how to gauge minor/major by ear is that if the music sounds striking, bold and solid, it’s likely to be a major key. If the music evokes emotion and tugs at your heart strings, it’s likely (though not guaranteed) to be in a minor key.

I’m a drummer at heart and have zero musical theory knowledge, so the way I was taught how to gauge minor/major by ear is that if the music sounds striking, bold and solid, it’s likely to be a major key. If the music evokes emotion and tugs at your heart strings, it’s likely (though not guaranteed) to be in a minor key.If you don’t want to delve too deeply into musical theory, you can work out the root of the key and be happy with that knowledge, and then simply use trial and error to find the best tunes to mix in. This isn’t much better than trial and error without knowledge of the theory, but it’s a step closer to harmonic mixing – and sometimes a step is all it takes.

Though it’s hard work and takes a lot of musical knowledge, working out the key (or just the root key) yourself is useful because as you listen to the tunes and find out the key, you develop an appreciation for what to listen to and eventually develop an ear to judge which tunes match together without the need to refer to a list of suitable tunes or a notation like the Camelot Easymix Sound System.

- Software: Computer programs are available that work out the key for you. One of these programs, Mixed in Key, analyses each of your music files and calculates what key it’s recorded in according to the Camelot system (see the earlier section ‘Camelot Sound Easymix System’). The program is surprisingly accurate, extremely effective and available from www.mixedinkey.com.

- Apps: There’s an app for that … Whether it’s an app that plays musical notes to help you work out the key using your ears, or an app that listens to a tune through your phone’s microphone and calculates the key for you, your smartphone is powerful enough to do the hard work for you. Search the iTunes and Android app stores for ‘harmonic mixing’.

Knowing how much to pitch

Your decks may offer you an 8 per cent pitch range or may let you go faster or slower by 100 per cent, but unless you have a special reason for going really fast or slow, if you go much over 5 per cent pitch then the majority of the music may start to sound strange to the ears of the people on the dance floor. If you have a master tempo control on your decks, you can play the music as fast or slow as you like and the pitch won’t change, just the speed, but I don’t suggest going much past the 10 per cent mark unless you’re trying to be creative.

How far you can push the pitch of a tune (without master tempo) depends entirely on the tune itself and the genre of music you’re playing. When playing rock sets, it’s rare that I go more than 3 per cent slower or faster – but I happily pitch loads of instrumental house tunes up to 12 per cent, and no one notices. (However, I never go past 5 per cent with most vocal tracks.)

You can transform some genres into something new by cranking up the pitch. A DJ I know used to play a 33 rpm house record at 45 rpm because it changed it into a great sounding drum and bass tune (though I don’t think that track had any vocals).

Like everything else in DJing, no hard and fast rule exists, but if you find yourself straying too far past 5 per cent it’s important to ask yourself whether the tune still sounds okay. The reason you need to increase (or decrease) the pitch by so much may be because you’re crossing genres – trying to mix a smooth house track into a trance track, for example. Although the structure, the key, the driving rhythm and the pitch of the tune may all sound fine, from a genre point of view you need to decide whether these tunes really play well next to each other. Like the bully and the cool kid at school, just because two tunes fit together like jigsaw pieces in many ways, it doesn’t mean that they’re meant to stick together. They may be from different jigsaw puzzles!

Developing a Style

The tunes you pick to play and the way you mix them come together to define your DJ style. Your style can and should be pliable depending on what club you’re playing in and what kind of music is expected of you.

Your style may also change from what you play in the bedroom and hand out on CD to what you play in a club. You may be a trance fiend in the bedroom, but the club you work at demands commercial dance music, so you have to tone down the music you play. This fact doesn’t pigeonhole you as a commercial dance DJ; it’s quite the opposite. You’re actually a well-rounded DJ: you can play top trance in the biggest clubs in the land, or play commercial tunes and tailor your set list to a mainstream crowd.

The genre of music you play doesn’t define how you put it together, though. Between key changes, tempo changes, energy and genre changes, you can put together your own unique style but also one that’s still aimed at the people you’re playing for – the crowd in front of you.

Easing up on the energy

Whether it’s rock music or dance music, if all you do is play music at full pace, full power, full volume all the time, the only thing you can do is slow down or reduce the energy. But if you’re almost at full energy, waiting to give more when the time’s right, you’re a DJ in control of the crowd or listener.

When playing live, try to take the crowd through different levels of emotions. Take them from cheering and smiling to a little more intense, eyes closed and hands in the air, and then back to cheering and bouncing up and down on the dance floor. If you can put together a musical experience instead of choosing 20 tunes just because they mix well with each other, you’ll be more creative and able to work the crowd, and hopefully will be regarded as a great DJ.

If you’re DJing at parties or rock nights, power and tempo can often play second fiddle to how well known a tune is. Consider the big tunes you play at parties – the energetic ones that get the most people onto the dance floor. If you play one after the other for two hours, everyone will be exhausted! In this instance, it’s good to think about using slower tracks to give people a breather (and others the chance to fall in love).

You’d do well to consider genres too, as a party/rock DJ. Playing Van Halen all night in a rock club may keep some people happy (me especially!) – but you risk alienating the fans of the harder stuff. And a seamless set of northern soul may sound cool to you at a party, but sometimes people just want to dance to Kylie!

Changing the key

Harmonic mixing (see ‘Getting in tune with harmonic mixing’, earlier in this chapter) isn’t just a way to let you mix in the next tune seamlessly: you can use key changes to step up the power of the night or take the set into a more intense, dramatic level.

When you want to come up for air from a deep place, I find that changing up in key so that the notes are slightly higher in pitch makes the mix sound brighter, happier and full of renewed energy. If you’ve spent a long time in the set playing dark, complicated trance or hard house tunes, a simple offbeat driving rhythm that changes the mix up in key can be like a strong espresso in the morning: it gives the mix and the crowd a burst of energy and leads you into a new part of your mix.

Increasing the tempo

For dance DJs, if the first tune you use in a mix is set to play at 130 bpm and you beatmatch all the tunes that followed precisely, the entire set plays at 130 bpm and bores the pants off the dance floor.

The normal progression of a set is to have an upward trend in beats per minute from start to finish, with a couple of tunes creating a speed bump by slowing the pace down by 1 or 2 bpm for a short period – then revving it all up again, which can work really well. Slowing down the set slightly for five minutes can add energy rather than kill the set.

The easiest way to increase the pace is to gradually increase the pitch fader through a series of tunes. If you have the patience (and length of tune to allow it), at the end of every two bars move the pitch fader by a small amount (about 2 or 3 millimetres). Spread out through enough tunes, you can get to the perfect number of beats per minute at which you want to play with no one noticing.

Be careful when moving the pitch control, because if you do it too quickly, the people on the floor will hear the music get higher in pitch (remember, it’s not just a speed control – it also changes the pitch of the music). If you have equipment with master tempo activated, which keeps the pitch the same no matter what speed you set it to play at, you can be a bit faster with this tempo change (about 15 seconds per bpm).

Jumps

If you don’t have the patience to stand over the tune and move the pitch control by small amounts, you can use the breakdowns and other changes in the tune to boost, or jump, the pitch by around half a per cent. Use the first beat of the bar on the new phrase to jump up the pitch control. How much you can increase the pitch, and whether you can spread this move over a couple of bars rather than the entire track, depends on the tune you’re playing.

If you’re planning to instantly jump the pitch as the tune hits the breakdown, do it between the last beat of the phrase and the first beat of the breakdown. You’re best doing this with tunes that don’t have a strong melody to the breakdown, and it takes practice and experimentation to get it right.

Genre changes

Switching from house to R&B or from trance to breakbeat (and eventually back again) can be an extremely effective and unnoticeable way of speeding up the mix, because the change in beat structure can hide the tempo changes.

Avoiding stagnation

When you think enough about the music you play and the order and style you play it in, you start to fall in love with a few mixes. I fell into this trap a few times, repeating the same series of mixes week after week or night after night. (This is especially common in warm-up sets, when you can wrongly assume that people don’t care about what or how you mix.)

- A mix that works in one club with one set of people doesn’t automatically work the next night with a different set of people.

- Regulars in the club recognise the mix and you appear uncreative.

- You just go through the motions; the fun and excitement has gone.

Because of the amount of time you spend practising, you should have a sixth sense about the options available to you when mixing in and out of tunes. For the sake of your development, the people on the dance floor and the tunes in your box that never see the light of day, don’t stick to the same transitions.

Respecting the crowd

Developing your own style is extremely important, but you still need to respect the crowd you’re playing to, especially when trying to get work. It’s one of those catch-22 situations that you can’t avoid: how do you gain the experience you need to get a job if you can’t get a job without experience?

If you’re a famous DJ, your style can be anything you want. Almost like the emperor’s new clothes, some folks will love what you’re doing no matter what you do or what you play.

But when you’re trying to build up your reputation or just starting off, you need to be careful about pushing the crowd past their comfort level. If the crowd expect to hear most songs playing normally, and you’re busy scratching, dropping samples and looping sections from some pretty freaky choices of tunes, you may lose the crowd, and it could be your first and last night! It may be your style, but it’s not the ‘house’ style.

Read the crowd and drop in your skills bit by bit over time, and who knows, as they get used to it, your style may become the house style!

Demonstrating your style

When you make a demo mix to show off your skills, your style is entirely up to you. (Head to Chapter 19 to find out more about making a demo.) Your demo is a reflection of who you are and what you want to do as a DJ. Show off how good you are at scratching, if that’s what you do, use your six decks past their potential, and add layers of effects and loops to create the most awe-inspiring mix anyone’s ever heard!

You’re not cheating if you listen to other DJs. When you’re not listening to new tunes or your own mixes, throw someone else’s mix on. Hearing how someone else does something in the mix can often inspire you to try something new and take the idea to another level.

You’re not cheating if you listen to other DJs. When you’re not listening to new tunes or your own mixes, throw someone else’s mix on. Hearing how someone else does something in the mix can often inspire you to try something new and take the idea to another level. A tune is made up of the backing track (the drums, bass line and any rhythmic electronic sounds) and the main melody and/or vocals. The backing track is the driving force to the tune, and within it is a rhythm of its own that is separate, but works in harmony with, the pounding bass beats. A great example of this is the duggadugga duggadugga duggadugga duggadugga driving rhythm in Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’.

A tune is made up of the backing track (the drums, bass line and any rhythmic electronic sounds) and the main melody and/or vocals. The backing track is the driving force to the tune, and within it is a rhythm of its own that is separate, but works in harmony with, the pounding bass beats. A great example of this is the duggadugga duggadugga duggadugga duggadugga driving rhythm in Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’. Although ta and ta-te are simpler and easier to beatmatch, they tend to be strong bass lines, and because they’re so strong they don’t always mix well. If the rhythm of one tune is ta and the other is the offbeat te (you don’t hear the ta from ta-te), unless the ta note from one tune and the offbeat te from the other tune are very similar, the mix can sound strange and out of tune. (See ‘

Although ta and ta-te are simpler and easier to beatmatch, they tend to be strong bass lines, and because they’re so strong they don’t always mix well. If the rhythm of one tune is ta and the other is the offbeat te (you don’t hear the ta from ta-te), unless the ta note from one tune and the offbeat te from the other tune are very similar, the mix can sound strange and out of tune. (See ‘