Chapter 15

Picking Up on the Beat: Song Structure

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding how songs are constructed

Understanding how songs are constructed

![]() Introducing beats, bars and phrases – and a certain sheep

Introducing beats, bars and phrases – and a certain sheep

![]() Working out where you are in a tune

Working out where you are in a tune

![]() Relying on your memory and instincts

Relying on your memory and instincts

![]() Trying out your skills on a sample structure

Trying out your skills on a sample structure

Being a good DJ means developing a split personality. One half of you plays tunes that the dance floor will love and the other half of you creates the perfect mix from tune to tune in the perfect order.

Being able to beatmatch doesn’t automatically make you an amazing DJ, especially if you’re mixing rock, indie or party tunes, which don’t lend themselves to beatmatching. How you adjust the EQs (equalisers) and overall sound level changes the dynamics of a mix (see Chapter 16 for more info), but the most important factor is choosing which parts of your tunes to mix over each other, and knowing when your tunes progress from introductions to verses to choruses and eventually to their last part. After all, whether you beatmatch or not, you need to know when your tunes are about to end!

Your knowledge of beat structure kicks in at this stage. Starting from the simple bar, which grows into a phrase, which blossoms into a verse – songs are mapped out in an extraordinarily ordinary fashion.

When you crack the code of how a tune is constructed, eventually you won’t need to think about it. Your instincts will take over to help you effortlessly create smooth transitions through your set that will bring you praise for your skills.

Why DJs Need Structure

The simplest of mixes involves playing the introduction (intro) of a new tune over the last part (the outro) of the tune you wish to mix away from. In order to start this mix in time, the DJ needs to know when the outro is about to start. By analysing how beats and bars are put together to make up intros, verses, choruses and outros (which I describe in detail in the section ‘Studying Song Structure’ later in this chapter), you won’t miss a beat.

Knowledge of beat structure is vital for all kinds of DJs. Whether your style is to create minute-long seamless transitions from tune to tune, or you fade up one tune as another ends, an understanding of how a tune is put together enables you to mix without any risk of gaps in bass drum beats, drops in the fun and energy of the night, or, even worse, silence.

Multiplying beats, bars and phrases

Just as a builder constructs a wall from hundreds of bricks layered on top of each other, and then adds that wall to other walls to make a house, a songwriter groups together the beats in a tune and adds these to further groups, and then joins these groups together to make larger structures, all of which are part of a bigger whole – the song.

But before you start looking at how walls make a house (or how verses and choruses make a tune), you need to know how to build a wall – or create a verse – out of beats and bars. The good news is that if you can count to four, you can easily deal with beat structure, because the building blocks of nearly all tunes you’ll encounter are grouped into fours:

- Four beats to a bar

- Four bars to a phrase

- Four phrases to a verse (normally)

I say ‘normally’ because, although typically made up of four phrases, the length of a verse can change depending on the decision of the songwriter.

How do I phrase this? How many bleats to a baa?

A bar comprises four beats in most house, trance and electronic dance music – and also in most rock, pop, country and party tunes. The easiest way to explain how these four beats become a bar and four bars become a phrase is with song lyrics.

Unfortunately, I’d have to pay a lot of money if I wanted to use the lyrics to a recent, famous song here, so instead I’ll use the nursery rhyme ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’ to show how the magic number four multiplies beats into bars and phrases.

The first line in this nursery rhyme is ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’, which lasts one baa – sorry, bar – in length. Each one of these words is sung on a different beat of the bar, and the first word has more emphasis than the next three have.

- Beat 1 – Baa

- Beat 2 – baa

- Beat 3 – black

- Beat 4 – sheep

Moving on into the nursery rhyme, this first bar is the first of four bars that make up the first phrase. Notice how these four lines/bars make up the first part of a story: a question is asked and then answered in a total of four lines/bars.

- Bar 1 – Baa, baa, black sheep,

- Bar 2 – Have you any wool?

- Bar 3 – Yes sir, yes sir,

- Bar 4 – Three bags full.

After this first phrase, the next phrase (four bars) moves the story on, giving more information: who the three bags are for.

- One for the master,

- One for the dame,

- And one for the little boy

- Who lives down the lane.

The next two phrases repeat the pattern: the first phrase asks the question; the second phrase gives more detail.

- Baa, baa, black sheep,

- Have you any wool?

- Yes sir, yes sir,

- Three bags full. (End of phrase 3; rhyme is 12 bars to here.)

- One to mend the jerseys,

- One to mend the socks,

- And one to mend the holes in

- The little girls’ frocks. (End of phrase 4; total duration is 16 bars.)

It’s easy to see why some would group together the first two and the second two phrases as two different parts of the rhyme, to treat it as two eight-bar phrases. But notice that those eight bars are very clearly split into two sets of four bars: both halves start with the identical ‘Baa, baa, black sheep, have you any wool? Yes sir, yes sir, three bags full’ phrase, but the next phrase is different.

The sheep can dance

Go back to your DJ setup and play one of your tunes – try to pick one with a very simple bass drum followed by a bass/clap drum pattern at the beginning.

When you hear the beats start playing, instantly start singing (or speaking) the ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’ nursery rhyme in time with the beats. On the downloadable example, when you get to the end of the rhyme, you’ll notice that the main melody starts playing. If it doesn’t, you either didn’t start singing on the first beat of the bar or you weren’t singing in time with the beats.

If you’re using your own tune for this, listen to the music when you finish the rhyme. Nine times out of ten, if you get the timing right, when you finish, either the melody will kick in or something very noticeable will change in the tune.

When you think you’ve got this, stop singing before anyone hears you!

Counting on where you are

It may already have occurred to you that not many DJs can be seen mouthing the words to ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’ in the DJ booth. Instead of relying on song lyrics to navigate the beat structure of a tune, DJs who are new to this concept count the beats as they are playing in a very special way.

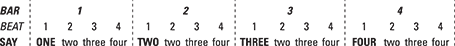

Go back to the start of the tune you played in the last section, and as the music plays, count along with the beats, as shown in Figure 15-1.

Figure 15-1: Counting along with the beats.

Count the bar number as the first beat of the bar. The point of saying the bar number first is simply so that you know which bar you’re on.

Hearing the cymbal as a symbol

Good DJs try to get away from literally counting the beats as they play as soon as possible. It’s quite simple to navigate through a track just by listening to what happens at the end of the four-bar phrases.

Going back to the ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’ nursery rhyme example, you know that if you hear ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’, you’re either in phrase 1 or 3. And the next line (either ‘One for the master’ or ‘One to mend the jerseys’) tells you whether you’re in phrase 2 or 4.

However, not all songs have lyrics to follow to let you know where you are in the tune. Even though music without lyrics sometimes has a change of the melody through the different phrases, you may need a little more guidance to help you pinpoint your position. If you’ve just dropped the needle or started the tune at a random point with a view to starting a mix, you need to know how to work out where you are in a four-phrase (16-bar) pattern.

The four phrases given in the ‘Baa, baa, black sheep’ example have three key, different types of ending:

- The end of the first and third phrase (probably identical)

- The end of the second phrase (the halfway point)

- The end of the fourth phrase (the final and most powerful point)

The end of the first and third phrase may have a small cymbal crash on the fourth beat of the bar or the first beat of the next bar. Or it may have nothing, which is just as useful as a cymbal crash; if nothing is at the end of the bar, then you know that you’re at the end of phrase 1 or 3.

The end of the second phrase, the halfway point, has a little more to it, because that first half exists as a discrete part of the story. This ending may have a small change to the drums, such as a mini drum roll or loss of bass drums, and end with a cymbal crash on the fourth beat or on the first beat of the next (ninth) bar.

So far, this means that if you don’t hear anything at the end of a phrase, you know you’re at the end of phrase 1 or 3. If you hear a small build-up, you know you’re at the end of phrase 2.

Then when you hear a much bigger, swelling build-up, you’re at the end of phrase 4 and the tune is about to progress into a new section.

Everything changes

Markers at the end of each phrase are common in some genres, but don’t assume they’ll always be there! Remember, rules are there to be broken. In the same way that some tunes elongate verses and choruses from 16 bars to 32 bars (and longer), removing the obviousness of these end-of-phrase markers can sometimes be what makes a tune feel different and special. This is especially the case with deep house music.

If some of the end-of-phrase markers are absent from a tune without lyrics, listen to how the music changes as the tune progresses. The main hook may start over, the melody may have a key change, another instrument may be introduced, another drum sound or synthesised sound may be added, or you may pick up on a general shift in the power of the music through the addition of filters or compressors – a feeling to the music rather than something that you can actually hear and define. All of these changes happen as a new four-bar phrase begins.

Actively listening to your tunes

To be an active listener you need to really listen to what’s playing. Rather than just sitting back and enjoying the music, concentrate on the sounds that you’re hearing: drum rolls, cymbal crashes, vocal samples (an ‘Oh yeah’ at the end of a bar is a good indicator!), changes in melodies or the bass line, strange whooshing, filter or other electronic noises; any of these sounds (or a lack of sounds) can be the marker that the songwriter has left to let you know where you are in the tune.

When you’ve cracked the beats/bars/phrases formula of how a tune is built, when you can identify the different end-of-phrase markers and when you’ve developed the instincts to be able to tell when the music is about to change, you’ll find that you no longer need to count out beats and bars as they play.

Spend time listening to your tunes so that you develop the memory and skill to be able to listen to a track halfway through and know where you are – not by robotically counting beats, but by listening for the end-of-phrase markers.

Studying Song Structure

The people on the dance floor aren’t really interested in how songs are made. However, they do anticipate and respond to the different parts of the music – just as you need to, too. As a DJ, you have to know when the tune is playing a verse, a chorus or a breakdown – even if the song has no lyrics – in order to create a seamless, error-free, professional-sounding mix.

Introductions, verses, choruses, breakdowns and outros are the different groups of bars and phrases that go together to create an entire tune:

- Introduction (or intro): The part at the very beginning before the main tune kicks in. Often 16 or 32 bars long, it can really be as long or as short as a piece of string, but usually consists of a multiple of two phrases (eight bars) in length, with normally a change or addition of instrument or sound every phrase (four bars). At the end of the intro there is usually a strong end-of-phrase marker (build-up, drum roll or cymbal crash sound) that lets you know that the intro is about to end.

The most DJ-friendly intro for beatmatching DJs lasts for at least 16 bars and is made up of just drum beats for the first eight of them. The second set of eight bars may start to introduce music such as the bass line to the tune. Chapter 14 tells you why this is so useful for beatmatching DJs, and also describes how to deal with different types of intros.

- Verse: In tunes with lyrics, each verse usually has different lyrics. If the tune has no lyrics, the verse is harder to discern, and though it may contain the main musical hook (the catchy part of the tune that you hum in the shower), it won’t be too powerful and energetic. In most cases, the verse lasts for 16 bars (four phrases), and is split into two sets of eight bars where the melody repeats itself but builds up through to the end of the 16th bar.

- Chorus: The part in the tune that normally has the same lyrics each time you hear it. The chorus is usually based around the melodic hook, and it’s the most energetic, catchy and powerful part of the tune. It’s shorter and more powerful than the verse, sometimes at only eight bars (two phrases) in duration, and it lifts the energy of the track (and the dance floor). You may find that the song includes a marker cymbal halfway to crash between the two phrases, and that it has a build-up out of the second phrase.

Even music without lyrics can have a verse and chorus. You find that the main hook that runs through the tune is quite subdued in one part, and then powerful, energetic and obvious in another part. The subdued section is the verse of the tune, and the more powerful, full-on section is the chorus.

This verse/chorus dynamic isn’t always the case. House music commonly bucks this trend of obvious changes, instead using subtle changes every two or four phrases to keep the tune progressing.

- Breakdown: The part where you can have a little rest. It’s a transition/bridge from the end of the chorus to the beginning of the next part.

To create a nice bridge out of the chorus and back into the next verse, breakdowns tend to be less powerful. The drums drop out, and the bass melodies and a reduced version of the musical hook play. The last bar of a breakdown has a build-up, like the end of a chorus or verse, and you may hear an indicator on the last beat of the bar or the first beat of the next bar, to let you know that it’s changed to a new part.

If the track includes a breakdown very early on, it’s likely to be quite short, lasting four or eight bars; this is known as a mini-breakdown.

The main breakdown occurs around halfway through a tune and probably lasts twice the duration of any mini-breakdown already heard. It’s typically 16 bars in length and follows the same sound design as the mini-breakdown, but has longer to get in and out, probably has fewer sounds and instruments to begin with and includes a crescendo (a build-up, like a drum roll getting louder and faster) for the last two bars or entire last phrase.

In indie, rock and party music, a breakdown in the middle of the tune is more commonly called a middle 8. It can follow the same principle I describe in the preceding paragraph, dropping power only to build back into the tune. But often the middle 8 is a twist to the tune, lasting eight bars (hence the name), still with drums, and building back into the main, familiar tune again when finished. The effect is the same, giving a break from the main sound of the tune, but the method can be different compared with trance/house music.

- Outro: The last part of the tune. Chances are, the last major element before the outro is a chorus. This chorus either repeats until the end, resulting in a DJ-unfriendly fade-out, or you will have a DJ-friendly outro.

The best kind of outro is actually a reverse of the intro. The intro starts with just beats, introduces the bass line and then starts the tune. If, after the last chorus, the music distils into drum beats, the bass melody and a cut-down version of the main melody for eight bars, and then the next eight bars are the drums and maybe the bass melody, you have 16 bars on hand that make mixing into the next tune easy (head to Chapter 16 for more).

Outros can last for a long time, though, going on for minutes! Every eight bars, the tune may strip off another element, until all you have is the hi-hat and the snare drum. Rather than a waste of vinyl (or bytes), this outro is extremely useful if you like to create long overlapped mixes. The trick is knowing how much of this reduced tune a mix will maintain. Chapter 16 is your guide for this.

Outros can last for a long time, though, going on for minutes! Every eight bars, the tune may strip off another element, until all you have is the hi-hat and the snare drum. Rather than a waste of vinyl (or bytes), this outro is extremely useful if you like to create long overlapped mixes. The trick is knowing how much of this reduced tune a mix will maintain. Chapter 16 is your guide for this.

Repeating the formula

The main blocks of the song are linked together by repetition and even more repetition, but with subtle changes throughout the tune:

- The second verse and chorus tend to be much the same as the first verse and chorus. If the song has lyrics, different verses have different sets of lyrics, but the chorus probably won’t change.

- Although the structure, melody and patterns remain the same, the music may introduce new sounds or effects to the original verse/chorus to create a new depth to the tune. (Changing the sound slightly gives the listener a feeling of progression through the tune.)

- As the breakdown or middle 8 drops the energy of the tune to its lowest point, a lot of songwriters like to follow it with a chorus – the most energetic part of the tune. Once again, the song may introduce more instruments and sounds to give the chorus a slightly newer feel.

- Depending on how long the tune is, the main breakdown may be followed by more verses, choruses and mini-breakdowns.

Accepting that every tune’s different

You’d soon get bored listening to tunes that were designed to the same structure, even if the music was different. In music production, altering the length of an intro, adding verses, choruses, breakdowns or mini-breakdowns, changing their length and extending outros are all part of what makes a tune unique while still following the basic four-beats-to-a-bar, four-bars-to-a-phrase structure.

The brain is an incredible organ. When you listen to a track with an active ear, after three or four run-throughs, your brain remembers the basic structure of the tune and then relies on triggers (such as the end-of-phrase markers, vocals or even just the different shades of rings on the record) that help you remember the structure of that track along with the thousands of other tracks in your collection.

Always listen with an active ear to the structure, the melody, the hook and the lyrics. Your brain stores all this information in your subconscious, calling upon these memories and your knowledge of how a tune is constructed from bars and phrases, ensuring that you never get confused during the mix.

Developing your basic instincts

Your memory and instincts for your music develop in the same way as they do when you drive a car. When driving, you don’t have to think ‘Accelerate … foot off a little … steer … straighten up … brake … clutch … check mirror … change to third … clutch … change to second … accelerate … ’ and so on, you just do it. You develop your instincts as a driver through practice and experience. It’s exactly the same with DJing.

You know that the first beat of the bar is emphasised. You know that the melody or line of a lyric is likely to start on the first beat of a bar. From listening to the tune, you know the kind of end-of-phrase markers that a certain tune uses at the end of a phrase, at the end of half a phrase and when it’s about to change to another element like a verse or chorus.

Listen out for these different end-of-phrase markers that tell you if you’re just halfway through the verse or about to enter a new part of the tune. Then you won’t have to rely on remembering lyrics or counting out beats.

Listening to a Sample Structure

After you know how beats become bars and bars multiply like rabbits (or sheep for that matter!) to become verses and choruses, the best thing is to go through the structure of an entire tune to start to decipher each part in a bit more detail.

- Intro: 16 bars

- Verse 1: 16 bars (4 phrases)

- Chorus 1: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Mini-breakdown: 8 bars

- Verse 2: 16 bars (4 phrases)

- Chorus 2: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Breakdown: 16 bars

- Chorus 3: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Verse 3: 16 bars (4 phrases)

- Chorus 4: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Chorus 5: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Outro: 16 bars

However, as I said, this is a very simple structure for a tune, and it’s very similar to a lot of party tunes and rock music. But if you’re looking to mix any genre of electronic dance music, remember that the structure will include sections that are a lot longer than above and may not be as clear-cut between verses and choruses:

- Intro: 48 bars (progressing in power through its 12 phrases)

- Verse 1: 32 bars (8 phrases)

- Chorus 1: 8 bars (2 phrases)

- Mini-breakdown: 8 bars

- Verse 2: 32 bars

- Chorus 2: 8 bars

- Breakdown: 32 bars

- Chorus 3: 8 bars

- Verse 3: 32 bars

- Chorus 5: 8 bars

- Outro: 48 bars (decreasing in power through its 12 phrases)

And remember: the way to develop the skill to intuitively pick up beat structure is to gain experience by spending time listening. Don’t count bars!

Digital DJs who use the sync function still need to know about the structure of their tunes. The sync function may make your bass beats play at the same time, and it might even pick the same beat in a bar to match – but it won’t pick the perfect or most creative place to start the mix.

Digital DJs who use the sync function still need to know about the structure of their tunes. The sync function may make your bass beats play at the same time, and it might even pick the same beat in a bar to match – but it won’t pick the perfect or most creative place to start the mix. Some guides on beat structure say that four bars make a phrase, and others say that eight bars make a phrase. Both numbers are valid, but I find my way through a tune more accurately when breaking it down into four-bar ‘chunks’. Four-bar phrases can also help when trying to create seamless mixes: waiting until the end of eight-bars to start a mix can sometimes result in four bars of basic bass drum beats before the melody in the next tune begins. So, if you don’t mind, I’ll stick to a phrase being four bars long.

Some guides on beat structure say that four bars make a phrase, and others say that eight bars make a phrase. Both numbers are valid, but I find my way through a tune more accurately when breaking it down into four-bar ‘chunks’. Four-bar phrases can also help when trying to create seamless mixes: waiting until the end of eight-bars to start a mix can sometimes result in four bars of basic bass drum beats before the melody in the next tune begins. So, if you don’t mind, I’ll stick to a phrase being four bars long. It makes sense when you’re learning, but you should try to move away from literally counting out beats as quickly as possible. Developing a reliance on beat counting in order to mix well can stifle your creativity and may end in disaster. Not only do you risk looking like Rain Man when you count the beats and bars as they roll by, but if something happens to throw your concentration and you don’t know where you are in the tune, the potential for the mix to turn into a nightmare is too big.

It makes sense when you’re learning, but you should try to move away from literally counting out beats as quickly as possible. Developing a reliance on beat counting in order to mix well can stifle your creativity and may end in disaster. Not only do you risk looking like Rain Man when you count the beats and bars as they roll by, but if something happens to throw your concentration and you don’t know where you are in the tune, the potential for the mix to turn into a nightmare is too big.