CHAPTER 15

THE KUMBAYA FALLACY

Do not be dismayed by the brokenness of the world.

All things break. And all things can be mended.

Not with time, as they say, but with intention.

So go. Love intentionally, extravagantly, unconditionally.

The broken world waits in darkness for the light that is you.

—L.R. KNOST

“How are you going to make world peace? Sit around singing ‘Kumbaya’?”

That’s a popular comeback from skeptics when they hear I do peacebuilding for a living.

For those of you unfamiliar with the reference, “Kumbaya” was a popular campfire song in the sixties. Imagine people with long hair, flowers in their headbands, sitting around a campfire holding hands, as someone gently strums the guitar singing:

Kumbaya, my Lord, Kumbaya.

Kumbaya, my Lord, Kumbaya.

Kumbaya, my Lord, Kumbaya.

Oh, Lord, Kumbaya

Someone’s crying, Lord, Kumbaya!

Someone’s crying, Lord, Kumbaya!

Someone’s crying, Lord, Kumbaya!

Oh, Lord, Kumbaya.1

People nowadays mock the belief that if everyone in the world held hands and sang “Kumbaya,” all our problems would go away.

I think this pervasive kumbaya image of peacebuilding in Western culture creates deep skepticism about real change. Too often peacebuilding appears to favor a soft approach to conflict that feels all warm and fuzzy but completely out of touch with the tough, gritty, messy reality of most conflict.

Most realists tend to side with Aristotle: “We make war to live in peace.” Force needs to be met with force, strength met with even greater strength, terror met with shock and awe.

Many people counseled me to not call the book Dangerous Love because dangerous love can be misinterpreted as weak, passive, and ill-equipped to deal with the structural realties we all face. When some people hear that “seeing people as people” or “dangerous love” is an antidote for much of what ails the world they think, “Oh, so what you are saying is that if I love someone, all my problems will be solved? Well, you don’t know my husband” (or “You don’t know my boss” or “You don’t know the North Koreans”). “You want me to love the person who’s standing in the way of everything I need? You want me to turn first? You’re right—that is dangerous. It’s also stupid. It doesn’t work that way.”

Three misconceptions are going on here:

Dangerous love is naive.

Dangerous love is passive.

Dangerous love can’t change the system.

Dangerous love is none of these. It’s the opposite: dangerous love is strong, it requires action, it can transform entire systems of conflict.

DANGEROUS LOVE IS STRONG

Dangerous love is geared toward implementing what motivates people to change. It isn’t restrained by the fear of appearing weak. If we worry about appearing weak, we once again are stuck in an inward mindset that is really about us, not others.

Fear of appearing weak also shows a fundamental misunderstanding about dangerous love. The love in dangerous love doesn’t imply a particular behavior. As The Anatomy of Peace teaches, we can do almost any behavior in two ways—even hard behaviors like disciplining or firing or going to war can be done while practicing dangerous love. And soft behaviors like complimenting or letting people get away with something they shouldn’t be doing can be done without any love at all.2

Loving others dangerously frees us up to treat them in exactly the way we should treat them—as people. Sometimes people need to be corrected, even fired. But we’ll never really know that until we see them as people.

The belief that dangerous love works with only certain individuals or groups—“good” people or “our” people, for example—misses the point completely. It’s meant to work with all people. As it turns out, people are never as good as we make them out to be and never as bad as our justifications want them to be.

In the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.,

We must recognize that the evil deed of the enemy-neighbor, the thing that hurts, never quite expresses all that he is. An element of goodness may be found even in our worst enemy. . . .

. . . There is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us. When we discover this, we are less prone to hate our enemies.3

When we fear conflict and can’t avoid it, we often believe that the solution to someone’s resistance is more resistance. In effect, we try to fight fire with fire. The belief that resisting the humanity of others shows strength and therefore makes peace is a mistaken one.

While showing strength and even using force can, at times, be effective conflict management tools, the more I resist others’ humanity, the more they are likely to resist me. In reality, water is a more effective tool to put out fires. Our discussion on collusion in chapter 11 walks us through the inevitable outcome of using war to make peace.

Once I see someone as a person, it should dramatically affect how I treat him or her. Not only does my mindset change, but my ability to love grows and expands in ways I never thought possible. When that happens, I will instinctively start to meet fire with water.

Several years ago, I was sitting on a rooftop in Jerusalem with a small group of Palestinian men. We often liked to go up there to talk and see the stars. We had just finished several days of a workshop together, and in the aftermath, a poignant conversation arose about dangerous love.

They were moved by the idea of seeing people as people. It resonated deeply with them. For many of them, that workshop helped them see Israelis as people for the first time in their lives.

But what to do next? That was the hard part. One of the people on the rooftop was a young man named Amir. He was well-educated, deeply connected to his Palestinian roots, and felt a moral obligation to resist what he believed was Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian lands.

“I appreciate this idea that we see the humanity of each other,” Amir began. “I kept thinking as I went through the workshop that we would be in a very different place today in Palestine had we done that from the beginning. We are suffering because of our failure to see each other as people, and we are passing this disease on to our children.

“But what is done is done,” Amir continued. “The Israelis have taken our land. I understand now why they did it, but it doesn’t make it right. I owe it to my children and my grandchildren to return this land to them.

“Our olive trees were planted hundreds of years ago by my ancestors,” he said with tears welling up in his eyes. “I have a responsibility to make sure they are cared for by my family. I must do everything in my power to make sure that our inheritance is not lost.”

Amir felt he owed it to his family to do everything he could to fight the growing takeover of his family’s home, their olive trees, and the land that their ancestors had lived on for hundreds of years.

“If we see them as people,” Amir continued, “we will be waving the white flag. They will take advantage of us, and we will lose everything. I know the way we are fighting isn’t working. But it seems better to die fighting for what we believe in than to sit passively by and let them take our past, present, and future.”

I felt for Amir. But I think—understandably, given the situation—he missed the deeper point. Resistance can be both a behavior and a way of seeing.

We can do almost any behavior while seeing someone as a person or as an object—even resist that person’s behavior. We can choose hard behaviors that include everything from protests and civil disobedience to, in some circumstances, war while seeing the person we are resisting as a person. In fact, sometimes it’s imperative, for the person’s well-being and our own, that we do so.

However, resisting people’s humanity is very different from resisting their behaviors or policies. The minute we’ve convinced ourselves that the problem isn’t the actions they’ve taken toward us but the fact that they are bad people, the moral foundation of our resistance evaporates.

Amir can find a way to resist what he believes are unjust actions by the Israelis while still not resisting the humanity of Israelis. Again, the words of Dr. King illuminate the kumbaya fallacy:

To our most bitter opponents we say: “We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We shall meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will, and we shall continue to love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws, because noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. Throw us in jail, and we shall still love you. . . . But be ye assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. One day we shall win our freedom, but not only for ourselves. We shall so appeal to your heart and conscience that we shall win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.”4

To live in peace, we have to prepare for peace. We prepare for peace by insisting on seeing those we disagree with as people.

When we see people as people, we create the space and ability to develop something John Paul Lederach calls our “moral imagination”—to come up with all sorts of possibilities and solutions to our problems that honor the humanity of others.5

That cultivation of our moral imagination is a direct result of our ability to project the I into the Thou, to see how we are connected, to see ourselves in a web of relationships with others, to seek solutions to problems that help all of us.

DANGEROUS LOVE IS ACTIVE

The second kumbaya fallacy is the belief that dangerous love is passive. That it exists entirely as some sort of inward state, that as long as I feel the right way about a person, all is well.

It’s not enough to say we see people as people. Our actions have to reflect that view for it to have any real power.

Dangerous love helps us become alive to others’ humanity, and it calls us to action. Ignore this call and we deny their humanity all over again, and the same vicious cycle of self-deception and justification start anew—usually with renewed vigor.6 However, the more we act upon the call, the more we open ourselves to the humanity of others and to the solutions to the problems that we are intertwined in.

An apology without change isn’t an apology. Accountability without correction isn’t accountability. Dangerous love without action isn’t really dangerous or love.

Just because we now see someone as a person doesn’t mean that the conflict has gone away. Anyone who has been involved in contentious negotiations or mediations knows just how stubborn and entrenched people can get. Two people can see each other as people and still be in conflict with each other. Problem-solving or conflict resolution is still a big part of the process.

Collaborative problem-solving is very difficult when people don’t trust each other and feel a constant, almost obsessive, need to protect their own justifications. To get to true, sustainable peace, we have to go beyond just managing conflict and even have to set aside problem-solving for a moment to get at the underlying relational issues—specifically, how I see others—to really transform conflict.

Conflict transformation solutions require operating at a much deeper level than behavior. They require us to dive down deep to the way we see each other. They require faith that people can change, that we as individuals can change, that we have the power within us to commit to see and live differently. They require me to make the first move, the most dangerous move.

However, that doesn’t mean that conflict resolution isn’t needed. We desperately need creative solutions to the problems that beset our relationships at home, at work, in our communities, and in the world.

Dangerous love helps us become cocoon thinkers in conflict instead of smog ones. And cocoon thinkers are the ones who not only transform relationships but also change entire systems that undergird and fuel conflict.

DANGEROUS LOVE CAN CHANGE THE WORLD

The third fallacy is that dangerous love can change personal relationships but can’t change the systemic conflicts that often underlie our personal conflicts.

In the late 1960s, peace studies scholar Johan Galtung started to see conflict in a transformative way. His work suggests that how we see conflict (and the people involved in it) profoundly impacts not only our personal relationships but also the way communities, cultures, and governments handle the problems we face in the world today.

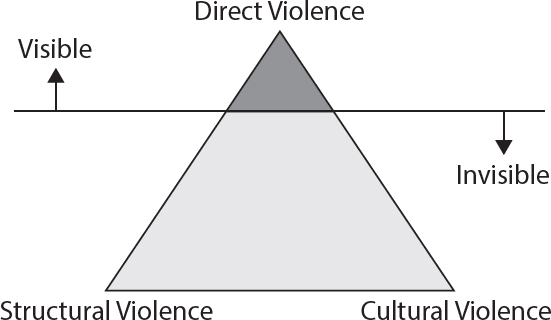

Galtung introduced the idea of “structural violence.” He argued that behind every incident of “direct violence” (both physical and emotional), you will find certain social structures that support or justify the direct violence.7

The best thinking at the time looked to inherent flaws in humanity as the source of conflict. Galtung’s view took this idea a step further by looking at the way institutions construct our reality and give us permission or even encourage us to act in violent ways.

In short, individuals alone aren’t to blame for violence, Galtung argued. Direct violence or conflict is symptomatic of something deeper. People have social systems (governments, cultures, religions, etc.) that give them legal or moral justifications to commit violence. If we attack direct violence at the source of the people committing the acts of violence but ignore the institutions that permit and even encourage seeing people as less important, it’s a bit like playing the game Whack-a-Mole. We can punish, imprison, or take out the people committing the violence, but more are coming and we’ll be in an endless loop of putting out fires.

In the early 1990s, Galtung began writing about an even deeper form of violence that he referred to as “cultural violence.” Galtung defined cultural violence as anything in our culture—art, music, religion, symbols, science, and so on—that makes direct or structural violence feel right or that legitimizes the use of violence against other human beings through dehumanization.8

Galtung introduced a violence triangle (figure 17) that shows the symbiotic relationship among these three forms of violence.

Galtung argued that to transform conflict, change agents had to attack not just direct violence or even the structural violence that undergirds it. They had to go deeper—to the culture that both justifies and supports the ongoing direct violence. Sustainable peace, he argued, depends on establishing peace at the cultural level—that is, at the level of how we see conflict and how we see others.

As long as our culture gives us justification for seeing other human beings as deserving or worthy of violence, we will create social institutions that reinforce that belief and continue to have the problem of direct violence. In fact, the more direct violence that occurs, the more cultural justifications will have to be created to support the direct violence. It’s a never-ending loop.

While violence might not describe this phenomenon at home or at work (though sadly sometimes, it does), the same ideas generally apply to how I see and treat my spouse, my children, my neighbors, employees, or managers. Until the basic cultural assumptions change, conflicts are unlikely to go away.

Galtung argued that if you really want big, sustainable peace, you have to attack the problem at its root—at the level of how we see, at the level of culture. Attacking it at the behavioral level alone—either directly or structurally—won’t get the job done.

Figure 17. Galtung’s violence triangle.

Adapted from Johan Galtung, “Cultural Violence,” Journal of Peace Research 27, no. 3 (August 1990): 291-305

Yet that is exactly what we do in conflict at home, at work, in the community, and in the world. We either run away from or attack the symptoms instead of getting at the heart of conflict.

Addressing conflict at the cultural or deepest levels promotes sustainable transformation in individuals, families, organizations, and communities. It leads, Galtung argues, from cultural peace to structural peace to, ultimately, direct peace.

Brené Brown, in her book Dare to Lead, writes about this cultural change by talking about living into our values. She writes,

A value is a way of being or believing that we hold most important.

Living into our values means that we do more than profess our values, we practice them. We walk our talk—we are clear about what we believe and hold important, and we take care that our intentions, words, thoughts and behaviors align with those beliefs.9

Dangerous love turns out be anything but passive. A change in the way one sees others always leads to action. And that action includes dismantling the structures that invite us to see others as objects and intervening whenever direct violence is occurring.

Creating peace at the cultural, structural, and direct levels is obviously easier said than done. It has proven difficult to figure out a replicable way to deal with issues at the cultural level that helps us concentrate on others’ humanity and engenders a sense of helpfulness, instead of hurtfulness, toward them. I believe it’s possible, especially if we’re willing to consider a different way of defining conflict—one that creates more hope in our collective future.

![]()

EXERCISE

DANGEROUS LOVE VALUES

Dangerous love requires intentionality. It takes practice. Reading a book like this and determining that we’re going to change the way we see others is a start. But most people find that they’ve established mental patterns of an inward mindset that are tough to break. They want to see people as people, but they have spent decades doing the opposite, and they won’t change overnight.

Many people who have gone through the workshops I’ve facilitated leave thinking “I’m never going to see my spouse/coworker/neighbor as an object again” only to find themselves reverting to an I-It orientation in a few hours or days.

Dangerous love takes time and patience to develop. It starts with little steps that we can take each day. In Dare to Lead, Brené Brown talks about the power of identifying values and then finding ways to make those values actionable.10

We’ve identified three critical values in this book that need cultivating:

Seeing people as people. This means that I have an outward mindset toward others. I see their needs, wants, and desires as equally valid as my own. Others are not vehicles for me to use. Or obstacles for me to overcome. Nor are they irrelevant to me.

Turning first. This is inside-outside transformation. To solve the most difficult problems in my life, I first look inward and ask myself, “In what ways may I not be seeing these people correctly? What assumptions have I brought to this conflict? In what ways might I be self-deceived?” It is the opposite of the blaming and dehumanization that often plague our conflicts.

Collaborative problem-solving. This means that when faced with conflict with another, I am committed to finding solutions that meet the needs of both of us. I will not avoid the conflict or give in. I won’t try to win the conflict or compromise. I will engage the person with respect for both that person’s needs and mine.

We need to do more than just hold these values. We have to put them into action every day. Here’s a modified exercise from Brown’s book11 that can be useful in turning our values into action:

Value 1: Seeing People as People

What are three behaviors that support this value?

What are three behaviors that contradict this value?

Choose one behavior that you can apply to the person you are in conflict with.

Value 2: I Turn First

What are three behaviors that support this value?

What are three behaviors that contradict this value?

Choose one behavior that you can apply to the person you are in conflict with.

Value 3: Collaborative Problem-Solving

What are three behaviors that support this value?

What are three behaviors that contradict this value?

Choose one behavior that you can apply to the person you are in conflict with.

Dangerous love takes work. Kumbaya isn’t going to get it done. The next few chapters tell stories of people who, in the midst of dangerous conflict, chose to turn first.