CHAPTER FIVE

DEFINING AND REWARDING SUCCESS

We have discussed how organization design is a means to implement strategy and how design decisions regarding the structure and lateral organization shape work flow, communication, power, and decision making in an organization. Regardless of the structure, employees make choices each day regarding how they work and interact. These choices are influenced by the unique combination of experience, personality, skill, and internal motivation that each individual brings to work. They are also shaped by the measures and rewards that the organization uses to communicate to employees what behaviors and results are most important. Creating these systems is an integral part of your design process. The final two steps on the star model are the design of reward systems and of people practices (Figure 5-1). While there is an inherent sequence in the first three points on the star—strategy, structure, then processes and lateral capability—the design of reward systems and people practices systems is closely linked and frequently done simultaneously. The order of these chapters doesn't imply a strict sequence in how these topics are considered.

Every organization has a different definition of success. Changing other parts of the organization design may mean that your organization's definition of success has changed. In order to perform at their best, people need a clear view of what success means in their organization—in terms of business results as well as individual performance expectations. While it is important that people understand the business strategy and how their work contributes to it, understanding the goal is usually not enough to shape behavior. There is no guarantee that people will use their skills, knowledge, and capabilities for the good of the organization. How people are measured and rewarded will influence how they carry out their work each day. The challenge of designing measurement and reward systems is to motivate and reinforce the behaviors that add value to the organization.

Figure 5-1. Star model.

Source: Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Organizations: An Executive Briefing on Strategy, Structure, and Process (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

Reward systems define expected behaviors and influence the likelihood that people will demonstrate those behaviors. They ensure that everyone is pulling in the same direction. An aligned reward system reduces internal competition and the frustration and diffusion of energy that comes when people are given competing goals.

Reward systems have four components:

- Metrics: The systems that identify measures and targets for enterprise, business unit, team, and individual performance

- Desired Values and Behaviors: The actions that are most likely both to produce desired business results and to reflect the organizational values

- Compensation: The monetary means intended to recognize a person's past contribution as well as motivate continued or improved performance

- Reward and Recognition: The nonmonetary components that complement compensation systems to let people know that they are valued

The first two components, metrics and values and behaviors, have to be addressed before the compensation and reward and recognition systems are designed. Metrics translate the strategy into the day-to-day actions and expectations of employee behavior. Metrics serve to clarify the vague terms used in vision statements that appeal to our emotions, pride, and sense of belonging—such as “superior service”—and turn them into concrete directives that appeal to our needs for measurable accomplishment and progress. Metrics take what are often abstract and intangible strategic concepts and make them meaningful to everyone in the organization. “You get what you measure” has become an axiom of organizational life. Given that measures can drive unintended behaviors as well as desired results, it is important to measure the right things.

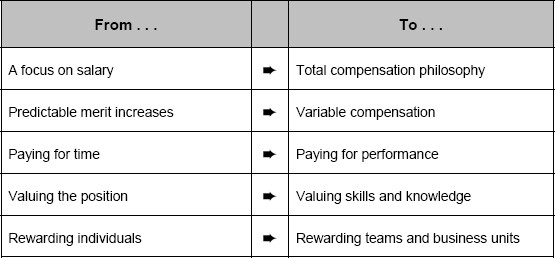

The trend in reward and compensation systems is to value people for the skills and knowledge they bring to the organization and how they use them, rather than for the particular position they are currently filling.1 This shift from job focus to person focus helps build a reconfigurable organization. It changes the definition of success from moving up a job ladder to increasing skills and developing additional capabilities that are of value to the organization.

This chapter summarizes recent thinking in the field of performance measurement and metrics and compensation and reward practices and provides tools to guide your design of measurement and reward systems. It is divided into four sections:

- Metrics describes six principles to consider when designing a performance measurement system.

- Values and Behaviors provides a process for defining the behaviors that will underlie the kind of culture that supports performance and success.

- Compensation reviews the advantages and disadvantages of different pay approaches.

- Rewards and Recognition presents a thought guide for creating noncompensation-based reward and recognition programs.

METRICS

Before you can reward people, you have to be able to measure their contribution. The design of any performance measurement system should reflect the operating assumptions of the organization. If growth is important, the metrics should stress growth objectives. If the organization competes on the basis of quality, then those should be featured prominently. Measurement systems can become quite complex as you attempt to measure and track all the dimensions of the organization. The design of sound metrics rests on six principles, which are summarized in Figure 5-2 and discussed in detail next.

1. BREADTH

Financial results are the foundation of business metrics. They are generally regarded as reliable and consistent. They provide hard data on which to base reward and accountability systems and they provide a performance measure consistent with the objective of generating profits for shareholders, which is a dominant pressure for senior management in public companies.

While financial measures are good for reporting past results to shareholders, they don't give managers the decision-relevant information that tells them what they must do differently to change those results.

During the 1990s, the concept of the “balanced scorecard” took hold as a way to broaden business metrics beyond financial measures and build a comprehensive view of the operational measures that impact business performance. The balanced scorecard was originally described by Kaplan and Norton in 1992.2 It includes four categories of performance:

Figure 5-2. Six principles of metrics.

| Financial | How do we look to shareholders? |

| Customer | How do customers see us? |

| Internal Business Processes | What do we have to excel at? |

| Innovation and Learning | How can we continue to improve? |

When using a balanced scorecard, you develop a set of performance indicators unique to your business for each performance category. Then measures are identified for each indicator focused both on short- and long-term results. The advantage of the balanced scorecard is that it allows the user to see if improvement in one area is being achieved at the expense of improvement in another. The balanced scorecard approach is now widely used. It has become a generic term to capture the idea of running a business based on a set of measures that reflect all of the important activities that impact the strategy.

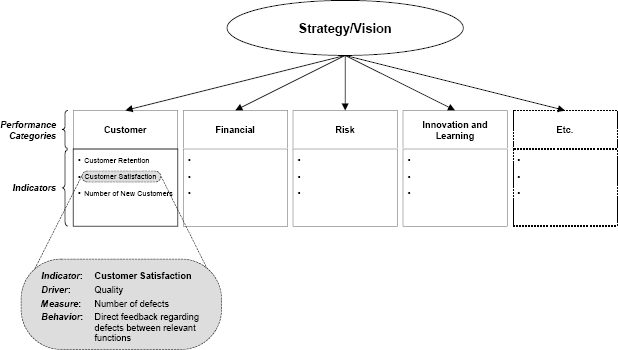

Figure 5-3 summarizes the steps for creating a balanced scorecard. First, the strategy and vision for the organization are translated into broad performance categories. Some companies have expanded Kaplan and Norton's original four categories to include such topics as People, Community/Environment, Strategic Cost Management, Risk, and even Partners to focus on contributions to sales by alliances, partnerships, and suppliers. The performance categories used should be selected to reflect the unique purpose and direction of your business.

Figure 5-3. Translating the strategy into measures and behaviors.

The second step is to determine a set of three to five performance indicators for each performance category. Performance indicators reflect the most important organizational capabilities that have to be developed or measured. They should be quite similar to the organizational capabilities you defined as design criteria in Chapter Two. Performance indicators should not be a comprehensive list of everything the organization must achieve, but rather what it must focus on. Some examples are given in Figure 5-4. The performance categories and indicators are likely to be consistent for the entire organization. How each indicator is then translated into specific measures will differ by unit, department, or function. For example, customer satisfaction might be an important performance indicator for your production, customer service, and finance functions. How it is measured in each department, however, will differ.

For each unit, the performance indicator is translated into drivers, measures, and behaviors, as Figure 5-3 illustrates for the performance indicator, “customer satisfaction.” Drivers are those components of performance that if changed positively or negatively, impact the performance indicator. A cause and effect relationship is believed to exist between the driver and performance. For example, customer satisfaction generally comprises a combination of quality, cost, timeliness, and convenience. But not all of these will be equally important for all businesses. If for a particular product or service, a change in delivery time has little or no impact on customer satisfaction, then it is not a driver and shouldn't be measured. In this example, which might be a production-oriented department, quality is a driver, and it is the driver of customer satisfaction that the production department has control over.

Figure 5-4. Sample performance indicators.

Once the drivers are identified, then a few measures can be determined that will tell you how you are doing. In this example, a key measure might be number of defects. Behaviors that impact the measure can also be identified. This department determined that timely and direct feedback among functions within the department is the behavior that is most likely to reduce defects overall.

The process of creating a balanced scorecard is iterative and ongoing. The framework stays the same, but measures may be added or dropped as conditions change or capability is built. If the organization has identified poor quality as a problem, measuring quality will help to provide the focus needed to improve it. Once a quality discipline is embedded, it may not be necessary to measure quality to the same degree. Other capabilities may become more important and need to be emphasized through inclusion in the scorecard.

2. CRITICALITY

The idea of broadening and balancing measures is powerful. A danger when developing any measurement system, however, is that everything gets measured. The act of gathering, analyzing, and interpreting the data lessens your ability to attend to other business. What is actually critical can get obscured. Some things to consider:

![]() Too many measures overwhelm the system. A rule of thumb is to limit any component in a measurement system to three to five items. Therefore, translate the strategy into three to five performance categories, identify three to five performance indicators for each category, determine three to five drivers for each indicator, and so on. It will keep people focused on determining what is most critical. One way to do it is to close your eyes, project yourself a few years out, and imagine that your strategy has failed. What went wrong? What failed? This intuitive, emotional component will complement the analytical approach and help determine which are the performance variables that really matter.3

Too many measures overwhelm the system. A rule of thumb is to limit any component in a measurement system to three to five items. Therefore, translate the strategy into three to five performance categories, identify three to five performance indicators for each category, determine three to five drivers for each indicator, and so on. It will keep people focused on determining what is most critical. One way to do it is to close your eyes, project yourself a few years out, and imagine that your strategy has failed. What went wrong? What failed? This intuitive, emotional component will complement the analytical approach and help determine which are the performance variables that really matter.3

![]() Not all measures are equally important. Among categories and within each category, measures should be weighted by importance. For example, community issues may be important enough to include as a category, but they may not be as critical to overall business success as customer or financial outcomes. Don't make the measurement system so all-encompassing that it doesn't provide guidance about priorities.

Not all measures are equally important. Among categories and within each category, measures should be weighted by importance. For example, community issues may be important enough to include as a category, but they may not be as critical to overall business success as customer or financial outcomes. Don't make the measurement system so all-encompassing that it doesn't provide guidance about priorities.

![]() Choose items that can be measured with confidence. There might be performance dimensions that would be nice to measure but data can only be collected manually or anecdotally. While no reporting system is 100 percent accurate, ad hoc spreadsheets are particularly prone to error, no matter how good they look. Whenever there is manual intervention, inaccuracies are introduced. If current systems don't allow information to be gathered with confidence, it will make for poor measures. People will tend to dismiss any feedback on their performance based upon such data. If the measure is important enough, then develop systems to gather the data with accuracy.

Choose items that can be measured with confidence. There might be performance dimensions that would be nice to measure but data can only be collected manually or anecdotally. While no reporting system is 100 percent accurate, ad hoc spreadsheets are particularly prone to error, no matter how good they look. Whenever there is manual intervention, inaccuracies are introduced. If current systems don't allow information to be gathered with confidence, it will make for poor measures. People will tend to dismiss any feedback on their performance based upon such data. If the measure is important enough, then develop systems to gather the data with accuracy.

3. TIME ORIENTATION

A robust measurement system needs to look backward and toward the future simultaneously. This can be accomplished through the use of lagging and leading indicators.

![]() Lagging indicators present past results. They tell you how you did and typically have a high degree of confidence and accuracy. But as the mutual fund companies caution, past performance is not always an indication of future performance. Relying solely on lagging indicators has been likened to steering a boat by examining its wake. They tell you where you've been, but not where you need to go.

Lagging indicators present past results. They tell you how you did and typically have a high degree of confidence and accuracy. But as the mutual fund companies caution, past performance is not always an indication of future performance. Relying solely on lagging indicators has been likened to steering a boat by examining its wake. They tell you where you've been, but not where you need to go.

![]() Leading indicators help to predict future performance. They are typically the drivers of performance that we discussed earlier. The indicator is assumed to correlate with some desired outcome. Leading indicators not only give early warning of problems and negative trends, but can also highlight future opportunities. They are more prone to inaccuracy than lagging indicators, however, because assumptions regarding causality may prove to be false.

Leading indicators help to predict future performance. They are typically the drivers of performance that we discussed earlier. The indicator is assumed to correlate with some desired outcome. Leading indicators not only give early warning of problems and negative trends, but can also highlight future opportunities. They are more prone to inaccuracy than lagging indicators, however, because assumptions regarding causality may prove to be false.

The challenge of measuring the success and value of a Web site on the Internet illustrates the challenge of developing good leading indicators. The first generation of metrics for valuing a Web site in order to set prices for advertisers was number of Web site hits—how many people visited the site in any given period. The assumption was that more visits meant more people were likely to “click” on a banner advertisement, and that click would result in sales for advertisers. The number of hits was the leading indicator. Owners of sites with large volumes of visitors were able to price advertising space and time higher than other sites. Unfortunately, after some time it became apparent that there was little correlation between the activity (number of visits) and the outcome (eventual sales). The popularity of the site didn't actually predict buying behavior. Analysis showed that the number of new visitors (“eyeballs” in cyberspeak) and length of stay (“stickiness”) were better predictors of sales for advertisers. Metrics and valuation formulas were changed accordingly.

In the diagram shown in Figure 5-3, the performance indicators are lagging indicators. Customer satisfaction is measured after the fact. The drivers, on the other hand, should be leading indicators. As product quality, on-time delivery, and accuracy increase and returns decrease, customer satisfaction can be expected to increase commensurately.

4. CONSEQUENCES

The purpose of having metrics is to influence your employee behavior. Although changing employee behavior is clearly the intent, there is a danger of creating unintended consequences that result from an imbalance among measures or from not thinking through the difference between the desired degree of behavior and too much of a good thing. Revenue growth is a common business goal. Setting it as a goal and measuring it focuses everyone on marketing, selling, and getting the product or service out to the customer. However, if revenue growth is not balanced by the goals of profitability and risk, revenue is growing but so are costs. Unless the explicit objective is to gain enough market share to lock out potential competitors, the business is no better off from the growth. Profitability remains the same. More dangerous is that the pace of marketing may outstrip the ability of the operational areas to deliver the product or service. Corners are cut, risks are taken, and the business craters when an ignored control problem explodes.

Call centers experience the dilemma of “you get what you measure even if that wasn't what you wanted” all the time. A classic example is the call center that rewards people for the number of calls answered per hour. Managers soon find that the quality of customer interaction drops as employees focus on getting to the next call. Customer problems don't get solved, but lots of calls get answered. In one center, there was no measure of repeat calls. Employees got high marks even if some percentage of the calls they answered were unsatisfied customers calling back. Most measures have a corollary that you need to be considered as a balance to avoid unintended consequences. For example:

- Increasing speed can lead to reductions in quality.

- Pressure to increase sales may result in sales to less desirable customers.

- Increased manufacturing volumes may lead to more shipped defects.

- Requiring on-time delivery can result in unsafe behavior.

Dominos Pizza experienced this last unintended consequence when it found that pizza delivery people were causing serious accidents, harming themselves and others, in their efforts to meet the company's promise of a hot pizza in thirty minutes or less. Most measures can result in unintended consequences when the relationship between the measure and behavior it is likely to provoke is not thought through.

5. ALIGNMENT

The final step in creating a system that defines and measures success is to ensure that all your metrics are aligned vertically—from the top of the organization down—and horizontally across units that must work together. Consistent goals:

- Define what an organization wants to/needs to accomplish in a given time frame.

- Provide a single purpose and direction around which the organization can focus energy and attention.

- Set the standards against which the organization's performance can be measured.

Goals and metrics should cascade down the organization and be communicated in relevant terms at each level. For example, profitability margins are a fine measure for a senior manager to focus on, but a team on the factory floor needs to know how increasing productivity in terms of units per hour translates into profitability.

The key is to cascade measures down. There is a danger of beginning the definition of measures at the front line and then rolling them up under the assumption that they will result in organizational improvement. A paradox of measurement systems is that organizational performance is not a simple additive function of the performance of individuals and units, but rather a result of the complex interrelationships of all the organization's component parts. So, what may seem like good measures because they encourage desired behaviors or results at the individual or team level, may in fact discourage some more subtle behaviors that will benefit the whole organization. Goals and measures also need to be aligned across the organization. If developed in isolation they can result in conflicts, particularly when units are interdependent.

6. TARGETS

As important as determining the measures is setting the targets. For example, a measure for a manufacturing unit may be number of defects. The target might be to hold defects to no more than one per 10,000. This number is meaningless, however, unless it is compared to a current baseline and external industry benchmarks. The right amount of stretch needs to be built in so that the goals are challenging but not impossible to reach.

Who sets the targets is another decision. Even in highly autonomous teams, managers usually need to be involved with setting targets. It is too tempting for people to set targets low in order to ensure that they can be met or exceeded, particularly when achieving the target is tied to compensation or other rewards.

Use Tool 5-1 to highlight any weaknesses in your current system.

VALUES AND BEHAVIORS

Behaviors are often an overlooked component of defining and rewarding success. Behaviors are not a design component. Rather they are the desired outcome of other design decisions. The logic is that the structure, processes, measurement and reward systems, and people practices encourage employees, and make it easy for them, to act in ways that support the goals of the business.

So, although behaviors don't get designed per se, they need to be made explicit. When they have been articulated and agreed upon by the organization, it will be clearer when other design choices fail to support the desired behaviors. In addition, they can be reinforced through choices made in the design of the reward and measurement systems.

Behavior is the manifestation of an organization's culture. No matter how clearly the organization's values are stated, it is the way that people act that defines the culture. Most organizations identify aspects of their culture that will need to change as a result of their strategy. The current state assessment will usually identify some dysfunctional behaviors, particularly among managers, that reduce the effectiveness of the organization. Changing the culture is difficult. The people who are in the current organization are there because they were attracted to the current culture and feel comfortable in it. Even if they say they would like it to be different, most of them contribute to reinforcing it every day.

Your organization's vision and values are the basis for defining the new behaviors that will be critical to shaping and creating the desired culture. Unfortunately, vision and value statements have become something of a cliche, an exercise for management to produce and proclaim before relegating to the shelf. It is true that most visions statements are indistinguishable and by themselves have little power. Further, few, if any, organizations have objectionable values in their value statement. The real work is to take these documents from the shelf and translate them into a corporate compass that guides employee behavior.

Values are the principles that a company stands for. Johnson & Johnson's response to the Tylenol scare of 1982 remains the hallmark of how a company's values shape decisions and behavior. After seven people died from cyanide-laced Tylenol capsules, management immediately made the decision to inform consumers, halt production, and pull 22 million products from store shelves. The decision was made and enacted without the need for a meeting among senior management. They all acted in concert, knowing that it was the right response. Almost twenty years later, a study conducted by Harris Interactive found that Johnson & Johnson was still rated as having the best corporate reputation in America.4 By contrast, the Bridgestone/Firestone company was roundly criticized during the summer of 2000 for initially denying any connection between documented car accidents and the quality of its tires, and for only reluctantly agreeing to provide replacement tires. Not surprisingly, in the same poll it was rated as having the worst reputation overall.

Federal Express is another company known for its strong values and the impact it has on performance. During the UPS strike in the summer of 1997, many new customers turned to Fed Ex. After the company was swamped with 800,000 extra packages a day, thousands of employees voluntarily poured into the hubs to sort them, visibly demonstrating the company's values regarding how it serves customers. It was only after the strike was over that employees were rewarded with extra pay tied to the profit gained during the strike.

As an organization is undergoing change, there may be behaviors that were highly functional in the old organization but which are detrimental in the new organization because they directly contradict new values. For example, the Lone Ranger–type decision maker may have been reinforced and rewarded in an organization where individual contributors had a high degree of autonomy. After the organization incorporates teams into its structure, this very same behavior would no longer be as desirable if the new values emphasized consensus decisions. Some of the behaviors and actions that are commonplace in your organization now will need to be stopped as new behaviors become the norm. Many of these can be deduced from the current state assessment. Two processes for turning vision and value statements into behaviors are outlined next. One uses storytelling to translate the vision. The second links behaviors to organizational values.

VISION STORYTELLING

People don't seem to have much capacity for remembering vision and value statements. Dry recitations of bullet points on slides at company meetings are quickly forgotten. Even the pretty brochures, posters, and wallet cards are stowed away and become background visuals. By contrast, people do remember stories. A number of companies are using stories to communicate their vision and make it a substantive part of the culture.

People remember stories better than facts, as our memory is episodic in nature. While people can generally remember just five to seven facts for an extended period, they can easily remember five stories, each one full of facts.5 When people recall experiences, they recall them in images. Linking facts or information to a ministory provides an image that can be recalled easier than the words.

Vision stories ask people to tell about a time they or someone else in the organization did something that illustrates the vision in action. The stories might be about going above and beyond the call of duty to help a customer or another department. They might illustrate trust, risk taking, or learning. By linking the element of the vision to a story, people can recall and relate the story to their own experience. They can share it with others. The stories, when used by managers, become the oral history that make employees into role models. When done as a group exercise, vision storytelling builds shared understanding of the behaviors that the organization values most.

Even if the vision is new and the organization is undergoing change, it is likely that people are already doing things that support the new direction. Gathering and sharing stories that illustrate the vision in action can reinforce these behaviors. The exercise reinforces what people are already doing right to support the organization's direction, even if it has changed. The act of sharing stories gives life and texture to behavioral norms.

Use Tool 5-2 to gather and share stories that illustrate the vision.

DERIVING BEHAVIORS FROM VALUES

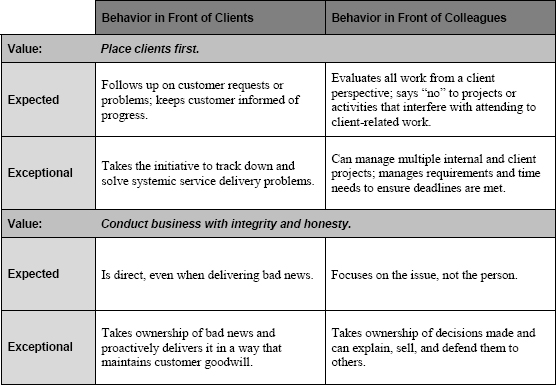

This activity is usually done initially with the leadership team, although other employees should be involved over time. For each of the organization's values, the group determines what an employee might do to demonstrate the value:

- In front of clients

- With colleagues

- With his or her own team (if a manager)

An example is shown in Figure 5-5. For each value, the leadership group of this organization identified how a generic value, such as “place clients first,” would “play out” in their particular organization in front of clients and in front of colleagues. For each value, two levels of behavior are defined: expected and exceptional. After additional refinement, these behaviors can be incorporated into the performance management and reward systems for reinforcement. Use Tool 5-3 to translate your organization's values into specific behaviors.

Figure 5-5. Sample values and actions.

COMPENSATION

Compensation is a fundamental tool for aligning behaviors to your organization's goals. When other elements of the design change, the compensation system may need to be updated as well. Compensation is commonly used to:

- Pay people for the time they give to the business.

- Acknowledge and reward past results.

- Motivate improved future performance.

- Retain employees.

You can think of compensation as giving employees both an income statement and a balance sheet. The income statement tells them how the company views their current contribution, their output for the year. The balance sheet reflects the person's overall value as an organizational asset. The challenge of creating effective compensation systems rests in sending the right messages through changes in pay. A pay raise is wasted if the receiver doesn't know what it is for. Is it because I did a good job last year? Is it because the market price for my job went up? Is it to let me know that I have potential and the company wants me to stay?

Although many would agree that poorly designed compensation plans can encourage the wrong behaviors, it is not so clear whether compensation on its own can have a significant positive impact on performance.6 The complex interaction between the work environment and the intrinsic motivation that employees bring to their work makes it difficult to sort out the impact of compensation on motivating sustained improvement. Inadequate compensation is clearly a source of dissatisfaction and can cause employees to leave the organization, but how potent money is as a motivator varies from individual to individual.

Over the past ten years, there have been some significant changes in compensation practices among U.S.-based businesses (Figure 5-6). These trends reflect an attempt better to link individual performance with overall business results, increase the flexibility of pay practices, and create compensation packages that will attract and retain scarce talent. Each is reviewed next.

Figure 5-6. Trends in compensation practices.

TOTAL COMPENSATION

Total compensation is the combination of salary, cash payments, and benefits received by an employee. For most employees below the very top executive levels, salary remains the largest component of their pay package. However, more and more companies are putting an emphasis on the total value of compensation packages, as opposed to just salary, to attract and retain employees.

One element is a greater use of bonuses and incentive pay above and beyond salary for all levels. In 1998, 72 percent of American companies offered at least one variable pay plan to employees, up from 47 percent in 1990.7 In addition, many companies are offering menus of benefit packages for employees to choose from, both to meet individual needs and to accommodate the different populations within an organization. For example, a recent study found that working mothers highly value control over their time and are less likely to leave a current job if it provides flexibility, not even for a higher salary at another position.8 Companies have introduced a whole range of new benefits, including on-site day care, concierge services, gyms, and free lunches, not only to make the work environment more inviting (and make it easier for employees to work longer hours), but also to increase the perceived total value of the compensation package.

VARIABLE COMPENSATION

Over the past few years, despite low unemployment and high competition for skilled workers, annual salary increases have hovered near 4 percent, just around the rate of inflation. Most growth in compensation has been in the form of variable compensation. Variable compensation comprises performance-based awards that have to be reearned each year and don't permanently increase base salaries. These can be in the form of cash bonuses or stock options. Over 60 percent of companies now use variable pay below the officer level.9

Some variable pay plans are in the form of “add-ons.” An employee's base salary is set at the market average, and any bonus or payout is in addition to that salary. Other firms, particularly cash-strapped start-ups, offer salaries well below the prevailing market but provide employees with an opportunity to come out far ahead of the market by earning variable pay. These are “at-risk” plans. If the target for the variable pay bonus isn't met (due to individual, team, or business reasons) the employees risk ending up worse off financially than peers in other companies.

Variable compensation provides a number of benefits for designing compensation systems, particularly when you want to encourage a more performance-oriented culture.

![]() Allows for differentiation in performance. Variable pay is a tool for rewarding excellence and differentiating top performers. Traditional merit-based compensation systems that give a yearly salary increase allow for little differentiation among employees. Typically, the difference in yearly salary increases is a few percentage points between below-average and outstanding performers. An old-line, tradition-bound insurance company that was trying to create a more nimble, performance-oriented culture, introduced a variable pay plan. Employees who were rated a 4 or a 5 on a five-point performance-rating scale each year would earn significantly more than those who earned a 3, which represented the average rating. In preparation, a study was conducted of past ratings in order to determine how many employees were likely to receive a 4 or 5 rating. Much to management's surprise, they found that over 65 percent of the company had been rated “above average” in the past year! Variable pay plans tend to reduce the sense of entitlement that pervades traditional plans. They give the whole performance management process more meaning by linking the outcome to significant impact on pay. Managers are forced to differentiate performance in order to justify bonuses. This is particularly important when a new organization design requires that people break out of comfortable modes of behavior and act in new ways.

Allows for differentiation in performance. Variable pay is a tool for rewarding excellence and differentiating top performers. Traditional merit-based compensation systems that give a yearly salary increase allow for little differentiation among employees. Typically, the difference in yearly salary increases is a few percentage points between below-average and outstanding performers. An old-line, tradition-bound insurance company that was trying to create a more nimble, performance-oriented culture, introduced a variable pay plan. Employees who were rated a 4 or a 5 on a five-point performance-rating scale each year would earn significantly more than those who earned a 3, which represented the average rating. In preparation, a study was conducted of past ratings in order to determine how many employees were likely to receive a 4 or 5 rating. Much to management's surprise, they found that over 65 percent of the company had been rated “above average” in the past year! Variable pay plans tend to reduce the sense of entitlement that pervades traditional plans. They give the whole performance management process more meaning by linking the outcome to significant impact on pay. Managers are forced to differentiate performance in order to justify bonuses. This is particularly important when a new organization design requires that people break out of comfortable modes of behavior and act in new ways.

![]() Holds down costs. Probably the biggest driver of variable pay plans is that it reduces overall costs for employers. Even when payouts are large, they are not permanently added to the base wages. Therefore they don't impact other costs that are calculated against salary, such as benefits and retirement contributions. When times are bad and goals aren't met, the company isn't stuck with an inflated salary base. Theoretically, this should provide more flexibility and avoid the need for as many layoffs during downturns, thereby benefiting employees with more job security.

Holds down costs. Probably the biggest driver of variable pay plans is that it reduces overall costs for employers. Even when payouts are large, they are not permanently added to the base wages. Therefore they don't impact other costs that are calculated against salary, such as benefits and retirement contributions. When times are bad and goals aren't met, the company isn't stuck with an inflated salary base. Theoretically, this should provide more flexibility and avoid the need for as many layoffs during downturns, thereby benefiting employees with more job security.

![]() Retains high performers. When variable pay is given in the form of stock options it can build long-term commitment to the organization and a sense of ownership. During the late 1990s, many companies increased the amount of stock they gave and, to compete with dot-coms, distributed it lower in the organization than they had in the past. The promise of wealth creation through ownership in a growing business lured MBAs and lawyers away from established corporations to Internet start-ups. Of course, this only works when the value of stock rises.

Retains high performers. When variable pay is given in the form of stock options it can build long-term commitment to the organization and a sense of ownership. During the late 1990s, many companies increased the amount of stock they gave and, to compete with dot-coms, distributed it lower in the organization than they had in the past. The promise of wealth creation through ownership in a growing business lured MBAs and lawyers away from established corporations to Internet start-ups. Of course, this only works when the value of stock rises.

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

The most prevalent compensation metric remains time. People are paid for how much time they work. Even those not paid by the hour are paid an annual salary on the premise that they will work a certain amount of time a year. Closely associated with variable pay is the trend toward pay for performance. Pay for performance rewards people for their results and contributions rather than their time and effort.

At the individual level, performance rewards are often given as bonuses for meeting certain goals. Pay for performance is also commonly tied to unit or division results. For example, when the unit achieves its objectives, a bonus pool is divided among all the employees in that unit.

Commissions for salespeople are the most common type of pay for performance. There is a clear link between results and compensation. Paying people in the organization for results rather than time and effort has proven to be a compelling idea and has taken a number of forms.

![]() Gain-sharing plans began in the 1940s as a collaboration between union workers and management in manufacturing plants and represent one of the earliest forms of paying for performance. The plans are based on the philosophy that workers should share in any of the gains that result from their contributions. A baseline of performance is established. If the business unit does better than the baseline measure, the workers share in the gains. The attractiveness of the plan is that it funds itself. Gain-sharing plans work best when the variables of productivity are under the control of employees and can be accurately measured. Gains are typically highest in the first years of the program when the easiest and most obvious improvements can be identified and addressed. Problems arise when all possible productivity improvements have been exhausted and the company is no more efficient or effective then competitors. Most plans are used as a way to stimulate productivity improvements and are then phased out after a few years.

Gain-sharing plans began in the 1940s as a collaboration between union workers and management in manufacturing plants and represent one of the earliest forms of paying for performance. The plans are based on the philosophy that workers should share in any of the gains that result from their contributions. A baseline of performance is established. If the business unit does better than the baseline measure, the workers share in the gains. The attractiveness of the plan is that it funds itself. Gain-sharing plans work best when the variables of productivity are under the control of employees and can be accurately measured. Gains are typically highest in the first years of the program when the easiest and most obvious improvements can be identified and addressed. Problems arise when all possible productivity improvements have been exhausted and the company is no more efficient or effective then competitors. Most plans are used as a way to stimulate productivity improvements and are then phased out after a few years.

![]() Business incentive plans are next-generation gain-sharing plans. They are widely used in a broad range of businesses to meet any number of goals and go by a variety of names. The goal in a business incentive plan is usually a strategic, financial, or operating outcome that management wants to focus everyone's attention on, such as profitability, cost, or customer satisfaction. A target and time frame are set. If they are met, everyone in that unit shares in the rewards. The advantage of these plans is that they can change with business needs. After the expiration of the time period, the targets shift in response not only to internal gains but to the competitive landscape as well. As the business reconfigures, so can the incentive plan. The challenge in designing these plans is to ensure that by focusing energy around a few important goals others are not neglected or compromised. Business incentive plans have to be adjusted periodically to ensure that the targets are fair and achievable and that they are motivating the right response.

Business incentive plans are next-generation gain-sharing plans. They are widely used in a broad range of businesses to meet any number of goals and go by a variety of names. The goal in a business incentive plan is usually a strategic, financial, or operating outcome that management wants to focus everyone's attention on, such as profitability, cost, or customer satisfaction. A target and time frame are set. If they are met, everyone in that unit shares in the rewards. The advantage of these plans is that they can change with business needs. After the expiration of the time period, the targets shift in response not only to internal gains but to the competitive landscape as well. As the business reconfigures, so can the incentive plan. The challenge in designing these plans is to ensure that by focusing energy around a few important goals others are not neglected or compromised. Business incentive plans have to be adjusted periodically to ensure that the targets are fair and achievable and that they are motivating the right response.

![]() Long-term incentive plans link rewards to company or business unit performance over a period of three to five years. They are usually reserved for senior executives. The intent is to foster long-term thinking in decision making as well as for retention. One large bank instituted them after finding that its aggressive program of rotating senior managers every two years was causing problems. The managers would make very short-term-oriented decisions to boost revenues during their tenure in the position, often leaving “the house a mess” for the next person taking over. In a common scenario, revenues would jump as a result of aggressive marketing and sales incentives. Few investments would be made, however, in infrastructure or customer support in order to keep expenses low. Just as the next manager was to take over, profitability would plummet as customer attrition increased due to service issues.

Long-term incentive plans link rewards to company or business unit performance over a period of three to five years. They are usually reserved for senior executives. The intent is to foster long-term thinking in decision making as well as for retention. One large bank instituted them after finding that its aggressive program of rotating senior managers every two years was causing problems. The managers would make very short-term-oriented decisions to boost revenues during their tenure in the position, often leaving “the house a mess” for the next person taking over. In a common scenario, revenues would jump as a result of aggressive marketing and sales incentives. Few investments would be made, however, in infrastructure or customer support in order to keep expenses low. Just as the next manager was to take over, profitability would plummet as customer attrition increased due to service issues.

The challenge with all pay-for-performance plans is identifying and measuring the behaviors and results that individuals or teams have control over and that will add up to the division or company performance that is desired. As was raised in the discussion of metrics, if on-time delivery is the goal, employees will find a way to achieve on-time delivery. The question then becomes, Does on-time delivery impact the overall financial performance of the company, and will singling it out and rewarding it compromise other important goals?

VALUING SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE

Another compensation trend is a shift from paying for a job to paying for a person. Skill-based pay (also called knowledge-based pay) values the skills and knowledge a person is able to contribute to the organization. Skill-based pay rewards learning and versatility. It has particular applicability:

- When the redesign requires the existing workforce to invest time and energy to develop new skills. Skill-based pay is a way to provide incentives that can make the transition easier.

- When the product of the company is knowledge (law, accounting, or consulting) and building knowledge is a source of competitive advantage.

- When there is a shortage of a particular skill in the marketplace. Technology companies frequently use skill “premiums” to help attract people to the company or encourage existing employees to learn sought-after skills.

Traditional compensation methods value a job, regardless of who is in it. When jobs are well defined, stable, and provide little opportunity for development within the job boundaries, this system works well. What many companies have found is that it doesn't work well in environments characterized by:

- Integration of activities across many individuals

- Fluid tasks and responsibility definitions

- High dependence on exchange of knowledge

- Interactions among multidisciplinary people

As more and more organizations fit this description, they are looking for ways to motivate and reward learning, collaboration, and the application and sharing of knowledge. The intent is to move away from a focus on jobs and job descriptions that can create “not my job” responses. To reinforce this, the word role is replacing the word job in many knowledge-work firms.10 Role conveys a set of responsibilities. The person's work and activities may change depending on what needs to be accomplished. The focus changes from what a person did or is doing at the moment to the larger contribution he or she is able to make.

Skill-based pay is often accompanied by broad banding of jobs—consolidating the number of job titles—so that people can earn more without having to be promoted into new jobs. Skill-based pay helps to encourage horizontal growth and lateral career moves. It works particularly well in new or high growth organizations where employees don't have well-developed skills and there is a business need to develop additional skills.

The application of skill- and knowledge-based pay plans may present you with some challenges.

![]() How do you know when a person has really acquired the new skill? Skills that are visible and straightforward, such as the operation of a particular type of machinery, are easy to measure. White-collar work skills can require more subjectivity. It is less clear-cut to determine when someone has mastered report writing or selling. A lot of management time and effort has to go into discerning levels of skill and how they will be measured and certified.

How do you know when a person has really acquired the new skill? Skills that are visible and straightforward, such as the operation of a particular type of machinery, are easy to measure. White-collar work skills can require more subjectivity. It is less clear-cut to determine when someone has mastered report writing or selling. A lot of management time and effort has to go into discerning levels of skill and how they will be measured and certified.

![]() Do you pay for only those skills that are used? People may develop skills that become obsolete or they may move on to positions where those skills are no longer needed. Policies have to be developed to address how these skills will be paid for or the business will be paying for something it doesn't value. One approach some businesses are trying is to give one-time bonuses for learning new skills rather than to increase base salaries.

Do you pay for only those skills that are used? People may develop skills that become obsolete or they may move on to positions where those skills are no longer needed. Policies have to be developed to address how these skills will be paid for or the business will be paying for something it doesn't value. One approach some businesses are trying is to give one-time bonuses for learning new skills rather than to increase base salaries.

![]() What if the learning can't be directly applied? Some organizations reward all learning—whether it is directly applicable to the work or not—in order to encourage a culture of learning. The organization has to decide whether it will reward a college degree or training certification even if it is in a field other than where the person is currently working. Employees may want to be rewarded for learning new skills that will position them for promotions even if those skills don't immediately benefit the organization.

What if the learning can't be directly applied? Some organizations reward all learning—whether it is directly applicable to the work or not—in order to encourage a culture of learning. The organization has to decide whether it will reward a college degree or training certification even if it is in a field other than where the person is currently working. Employees may want to be rewarded for learning new skills that will position them for promotions even if those skills don't immediately benefit the organization.

![]() When do people get training? Finding time for training is a challenge for any organization. Some organizations do on-the-job training by peers, others develop training modules and classes. The opportunity to attend training has to be equal if people are to be able to gain skills equally.

When do people get training? Finding time for training is a challenge for any organization. Some organizations do on-the-job training by peers, others develop training modules and classes. The opportunity to attend training has to be equal if people are to be able to gain skills equally.

REWARDING TEAMS AND BUSINESS UNITS

Organizations are relying more on team- and unit-based compensation than they have in the past. If your organization design assumes cooperation will be necessary because of the interdependence and complexity of the work, then the work should be motivated and rewarded through rewards that don't just focus on more than individual contributions. Team and unit incentives usually combine aspects of performance and skill-based pay.

![]() Performance Incentives. A performance goal is set for the team or business unit. It may be based on hard criteria, such as cost savings, output achieved, or deadlines met, or it may include some softer criteria, such as effective problem solving. When the goal is met, a bonus is given, either in the form of cash, stock, or noncash rewards. When it is linked to a gain-sharing or profit-sharing plan, the amount is tied to the overall financial performance of the unit.

Performance Incentives. A performance goal is set for the team or business unit. It may be based on hard criteria, such as cost savings, output achieved, or deadlines met, or it may include some softer criteria, such as effective problem solving. When the goal is met, a bonus is given, either in the form of cash, stock, or noncash rewards. When it is linked to a gain-sharing or profit-sharing plan, the amount is tied to the overall financial performance of the unit.

![]() Skill-Based Pay. Teams can be rewarded for the collective skills they accumulate. The team is not rewarded until all team members reach a certain level, in order to encourage the more skilled employees to help others achieve competence. It is most commonly applied in team settings where the tasks of the team are specific and measurable and where there is a desire to make the team more flexible and autonomous by increasing the skills of all team members. As each team member learns and applies the skills that are needed by the team overall, that person's pay is increased. Team members cross-train in the work of others in order to lessen the impact of absenteeism on productivity. People are also rewarded for developing management skills. As these responsibilities are moved to the team, the organization can reduce the number of managers needed.

Skill-Based Pay. Teams can be rewarded for the collective skills they accumulate. The team is not rewarded until all team members reach a certain level, in order to encourage the more skilled employees to help others achieve competence. It is most commonly applied in team settings where the tasks of the team are specific and measurable and where there is a desire to make the team more flexible and autonomous by increasing the skills of all team members. As each team member learns and applies the skills that are needed by the team overall, that person's pay is increased. Team members cross-train in the work of others in order to lessen the impact of absenteeism on productivity. People are also rewarded for developing management skills. As these responsibilities are moved to the team, the organization can reduce the number of managers needed.

Rewards based on collective effort and outcomes have some potential hazards.

![]() Distinguishing Which Organizational Level to Reward. Team incentives work well to motivate members within the team but may create conflict or even competition between teams. This can be avoided by creating business-unit-level plans that reward the contribution of all teams and employees when there is interdependence among the teams. On the other hand, the danger of setting performance goals to be rewarded at too high a level in the organization is that the line of sight between the team's action and their results is blurred. The responsibility for achieving the goal becomes diffuse and the motivational aspects of the incentive are lost.

Distinguishing Which Organizational Level to Reward. Team incentives work well to motivate members within the team but may create conflict or even competition between teams. This can be avoided by creating business-unit-level plans that reward the contribution of all teams and employees when there is interdependence among the teams. On the other hand, the danger of setting performance goals to be rewarded at too high a level in the organization is that the line of sight between the team's action and their results is blurred. The responsibility for achieving the goal becomes diffuse and the motivational aspects of the incentive are lost.

![]() Free Riding. Controls need to be in place to ensure that group members who don't contribute their share don't benefit, or at least don't benefit for long. Only a few organizations reward people based completely on team performance. Most mix individual measures and rewards with a team component to control for differences in individual contribution.

Free Riding. Controls need to be in place to ensure that group members who don't contribute their share don't benefit, or at least don't benefit for long. Only a few organizations reward people based completely on team performance. Most mix individual measures and rewards with a team component to control for differences in individual contribution.

![]() Allocating Rewards. Even if all members of the team or unit contribute equally, there is the problem of how to allocate the rewards: by percentage of salary or in equal amounts. If the payout is a percentage of salary, then some people will get more than others, unless all earn exactly the same amount. On the other hand, an equal amount will mean that some will find the reward less meaningful because it represents a smaller portion of their total compensation.

Allocating Rewards. Even if all members of the team or unit contribute equally, there is the problem of how to allocate the rewards: by percentage of salary or in equal amounts. If the payout is a percentage of salary, then some people will get more than others, unless all earn exactly the same amount. On the other hand, an equal amount will mean that some will find the reward less meaningful because it represents a smaller portion of their total compensation.

DESIGNING COMPENSATION SYSTEMS

Changes in compensation practices typically lag behind other change initiatives due to the time it takes to study a pay system, reevaluate jobs, pilot the new plan, and roll it out. Management tends to be conservative when contemplating compensation changes. As a result, most systems:

- Are based on custom, tradition, habit, and administrative convenience.

- Tend to maintain the status quo since compensation is a highly sensitive employee issue.

- Are expensive to change in terms of studies required, implementation of new systems to capture data, and the management time required to reach agreement on standards.

New pay systems also exact a psychological cost on employees, which has to be anticipated and managed. Putting a higher percentage of compensation at risk is good for companies. It allows them to move dollars out of the fixed-cost category and into the variable-cost category, and it provides tangible evidence that things must change. For employees, however, it means trading something that is sure—base pay tied to time and seniority—for an incentive that may or may not be paid out. There are a few things to consider when contemplating introducing new pay structures:

![]() Is there agreement on what is important and is there a way to measure it? Any rewards given for meeting specific production, quality, or service goals need to have clear criteria. Without clear measures, decisions made by supervisors and managers can seem arbitrary and create resentment between business units if some managers are perceived as easier than others.

Is there agreement on what is important and is there a way to measure it? Any rewards given for meeting specific production, quality, or service goals need to have clear criteria. Without clear measures, decisions made by supervisors and managers can seem arbitrary and create resentment between business units if some managers are perceived as easier than others.

![]() Are rewards for changes in behavior built into the system? Some work needs to be done as part of the planning process to identify the behaviors that people need to do more of—and less of—to impact the culture and business results. Although the management team can determine these behaviors, involving a representative sample of the people impacted will improve the result. They will identify the management behaviors that need to change in addition to what they and their peers need to do differently. They will also ensure the language is direct and descriptive. Finally, the involvement process will increase buy-in to the overall plan.

Are rewards for changes in behavior built into the system? Some work needs to be done as part of the planning process to identify the behaviors that people need to do more of—and less of—to impact the culture and business results. Although the management team can determine these behaviors, involving a representative sample of the people impacted will improve the result. They will identify the management behaviors that need to change in addition to what they and their peers need to do differently. They will also ensure the language is direct and descriptive. Finally, the involvement process will increase buy-in to the overall plan.

![]() Are people enabled and empowered to control the variables? It is impossible to ask people to excel if they are not enabled to achieve excellence. Whether it is pay for performance, skill-based pay, or some team incentive plan, it will only work when the people participating have some control over the outcome. Nothing is less motivating than for a person to work as hard or harder than before, meet their personal goals, and find out there is no upside because of factors out of their control. These could include:

Are people enabled and empowered to control the variables? It is impossible to ask people to excel if they are not enabled to achieve excellence. Whether it is pay for performance, skill-based pay, or some team incentive plan, it will only work when the people participating have some control over the outcome. Nothing is less motivating than for a person to work as hard or harder than before, meet their personal goals, and find out there is no upside because of factors out of their control. These could include:

Another business division not making their goals

Lack of reasonable authority to make decisions and solve problems

Lack of tools and resources to do the job well

![]() Is the performance management system adequate? Performance management processes are closely linked to compensation and reward systems. No matter how solid the metrics or innovative the compensation system, if managers don't set goals, coach their people, and give candid feedback, the outcome will be compromised. There's no one best system among the all the performance management systems available. The scales, forms, and process are less important than the consistency and honesty with which they are applied.

Is the performance management system adequate? Performance management processes are closely linked to compensation and reward systems. No matter how solid the metrics or innovative the compensation system, if managers don't set goals, coach their people, and give candid feedback, the outcome will be compromised. There's no one best system among the all the performance management systems available. The scales, forms, and process are less important than the consistency and honesty with which they are applied.

![]() Is there a plan for when times are bad? Alfred Lord Tennyson said, “’Tis better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all.” The same may not be true of variable compensation. It is hard to have it one year and lose it the next. Some people are comfortable with wide fluctuations in their pay, but a lot of people join corporations for the predictability. They will be unhappy if a down business cycle means they make less for the same amount of work. Many start-up dot-coms that gave stock instead of salary or bonuses found that people were all too ready to jump ship when their stock options became worthless, no matter how exciting the work environment.

Is there a plan for when times are bad? Alfred Lord Tennyson said, “’Tis better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all.” The same may not be true of variable compensation. It is hard to have it one year and lose it the next. Some people are comfortable with wide fluctuations in their pay, but a lot of people join corporations for the predictability. They will be unhappy if a down business cycle means they make less for the same amount of work. Many start-up dot-coms that gave stock instead of salary or bonuses found that people were all too ready to jump ship when their stock options became worthless, no matter how exciting the work environment.

![]() Can the system be manipulated? Time is easy to measure. Jobs can be compared externally and their value set. Once you get into valuing skills, rewarding learning, and creating complex incentive plans based on softer performance measures, you introduce opportunity to manipulate outcomes. Create pay plans that are simple, valid, and transparent so that the outcomes can be neither debated nor perceived as unfair.

Can the system be manipulated? Time is easy to measure. Jobs can be compared externally and their value set. Once you get into valuing skills, rewarding learning, and creating complex incentive plans based on softer performance measures, you introduce opportunity to manipulate outcomes. Create pay plans that are simple, valid, and transparent so that the outcomes can be neither debated nor perceived as unfair.

![]() What is the time orientation? The closer rewards and compensation are given to the time when the goal is met, the more motivating and reinforcing it will be. A mix of short-term and longer-term rewards will ensure that while current actions are rewarded, it is not done at the expense of long-term goals.

What is the time orientation? The closer rewards and compensation are given to the time when the goal is met, the more motivating and reinforcing it will be. A mix of short-term and longer-term rewards will ensure that while current actions are rewarded, it is not done at the expense of long-term goals.

Use Tool 5-4 to assess how well your current compensation systems build cross-unit skills and capabilities and contribute to a reconfigurable organization. Be sure to allocate time and resources to the evaluation of your compensation system as part of your design activities.

REWARDS AND RECOGNITION

Reward and recognition programs complement compensation as a way to let employees know they are valued and to communicate what the company believes is important. They are another tool in the organization design process for aligning behaviors to business outcomes. They are valued in the reconfigurable organization because they are easily implemented and customized to meet the needs of specific teams or work groups. Unlike compensation systems, reward and recognition programs don't require significant investment in design time, although they must be well-thought-out, of course, to be effective.

A major difference between reward and recognition programs and compensation is that recognition has a public aspect—the company communicates its values and priorities through the choice of what achievements and behaviors it recognizes and rewards. If the redesign requires that the organization build new capabilities and that people work together in new relationships, rewards and recognition can quickly and publicly reinforce when things go right. A well-designed reward and recognition program can:

- Support business goals by reinforcing desired values, behaviors, and results.

- Build a high-performance organization by creating an environment in which people want to perform to the best of their abilities.

- Increase retention by communicating each employee's importance to the success of the organization, and by building a sense of belonging and pride.

“REWARD” OR “RECOGNITION”?

Most people use the words reward and recognition interchangeably. Although the meanings of the two words overlap, there are important differences.

| Rewarding | Communicates: “Do this” and you will “get that.” Focuses on extrinsic motivations (tangible paybacks). Is usually delivered through a centralized program. |

| Recognizing | Communicates: “The work you do is meaningful, and you've done it well.” Reinforces intrinsic motivations (positive feelings about work). Requires new management behaviors. |

Too often, reward and recognition programs focus primarily on rewards and fail to address the underlying behaviors and work environment issues that they are intended to improve. When designing a program, conscious consideration should be given to maintaining a balance between recognition and rewards.

THE FOUR DIMENSIONS OF RECOGNITION

Within any organization there are dozens of things that employees do that can be recognized. What you choose to focus on sends a clear message about what is most important to the company at this point in time. Recognition opportunities can be grouped into four dimensions: goals and results, values and behaviors, special achievement and effort, and overall contribution (see Figure 5-7). When any one dimension is rewarded to the exclusion of others, just as with any performance measurement system, unintended and undesired outcomes can occur.

GOALS AND RESULTS

Most commonly, reward and recognition programs are established to boost productivity. However, when rewards and recognition are given only for meeting production targets, people tend to focus on the ends over the means. If salespeople are rewarded for quantity of sales, they have little incentive to worry about the quality of the customer or the long-term value of the customer to the business. The same issues identified in the Metrics section regarding unintended consequences apply to reward and recognition programs.

VALUES AND BEHAVIORS

Values and behaviors are the basis of the organizational culture, influencing not only employee morale, commitment, and satisfaction, but ultimately the customer experience as well. The behaviors that are rewarded need to balance improving internal interactions (e.g., between managers and employees or between business units) as well as those that more directly influence customers.

Rewarding only values and behaviors can result in people losing sight of business results. For example, in one company a program intended to promote teamwork encouraged people to increase the number of meetings held, memos circulated, and people involved in projects. Without any measure of outcomes, however, there was no way to ensure that all of this activity produced a better business result.

Figure 5-7. The four dimensions of recognition.

SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT AND EFFORT

The plan should include opportunities to highlight the contributions of the few—whether for a money-saving idea or perfect attendance—while still honoring the majority who constitute the “backbone” of the organization.

Steady performers who are responsible for managing the continuity of the business need to feel that they have an opportunity to achieve at least some of the rewards and that they aren't left out of the game. For example, many employees are content to do their jobs and don't have aspirations to become managers or project leaders. They aren't interested in taking on the special projects that might earn them glory. But they still want to be appreciated and recognized for their contribution day in and day out.

OVERALL CONTRIBUTION

If everyone is rewarded the same way regardless of contribution, or if recognition is given only to teams and never to individuals, high performers may feel their contributions are taken for granted. They may continue to be high performers, but they may resent that others share the glory resulting from their achievements.

DETERMINING WHAT REWARDS ARE MEANINGFUL

A recognition plan can't fix fundamental problems that create barriers to excellence. Putting a plan in place as a “Band-Aid” without simultaneously addressing some of these problems can cause the plan to backfire and actually reduce morale.

A key question to ask is, “Are people paid fairly?” Although most people would like to be paid more, most will admit when they are paid fairly compared to their peers and the marketplace. On the other hand, when people believe that they are not fairly compensated for their work, the introduction of a reward and recognition program, especially if it involves cash payments, can have negative impacts. Small payments will be seen as insulting, and managers will try to use larger rewards to make up the compensation gap for their high performers. Adjustments to salary levels to reflect the local marketplace should be made before rolling out a recognition plan.

As discussed above, the first component of the program design is determining what outcomes and changes are important to the organization. The second component is determining what is meaningful for the employee to receive in exchange for making an extra effort.

THE PROBLEM WITH MONEY

Money is the most obvious reward. No one ever says he or she wouldn't like more money. It's also easy to administer. The award can be added right into the next payroll check. But money has some drawbacks as an effective reward in a recognition plan:

- Money is too easily confused with compensation. It looks the same and is administered the same way. When the reward and recognition program becomes a means to make up for perceived shortfalls in compensation or bonus, the message becomes confused.

- Money can become an entitlement. Someone who makes the production target every month begins to count on the extra cash. It then feels “taken away” when the program stops or the target is raised.

- Money disappears. For most people, the money is put into the wallet and used for general expenses and bills.

- Finally, money leaves nothing memorable or tangible to reinforce what went well. Few people go out and buy something special to remind themselves of the recognition.

On the other hand, it is difficult for most managers to know their teams well enough to choose a nonmonetary reward that will be appreciated and meaningful. Most of us have a hard enough time choosing gifts for our friends and relatives, much less for the people with whom we work.

PROVIDE PEOPLE WITH A CHOICE

One way to avoid putting your managers in the position of guessing what people would like for rewards is to use one of the many incentive plan vendors. These third-party companies can help develop a “catalog” of rewards that plan participants can choose from. The catalog is customized to the needs of the business and can include general merchandise, company logo merchandise, as well as local gift certificates and memberships. The catalog can even include things like time off. Typically, participants are given “points” for achieving goals, demonstrating behaviors, special achievements, etc. The number of points, who can award them, and when they are given become part of the program guidelines unique to each organization.

Another advantage of this approach is that even though the points have an underlying monetary value (and ultimate cost to the company), the connection is not explicit, which therefore delinks the whole process from compensation and money.

Merchandise/tangible rewards work best when combined with other types of recognition, such as thank-yous, certificates, public acknowledgement of achievements, and celebrations. In this way the key messages are reinforced verbally and the person receives a tangible, valuable reminder of the achievement.

Such a system, however, shouldn't preclude managers and management from buying something when appropriate. Often a small reminder for the desktop—a team picture, small plaque, or coffee cup with the name of the project—can be a continual reminder for the person, and for others who see it, of what was achieved.

SUGGESTED DESIGN APPROACH

The previous discussion suggests the following approach to designing a reward and recognition program: Create a formal, time-bound “program” that focuses attention on one key message for the near term. At the same time, embed recognition into the culture and management skill set for the long term.

1. CREATE A PROGRAM

A program is what most people think of when they hear of rewards and recognition. The benefits of a having a program include:

- Programs are highly visible and attract attention. They often have a theme that can link to other initiatives, communication opportunities, and events.